Abstract

Abstract

Despite the growing number of women living with and affected by HIV, there is still insufficient attention to their pregnancy-related needs, rights, decisions and desires in research, policy and programs. We carried out a review of the literature to ascertain the current state of knowledge and highlight areas requiring further attention. We found that contraceptive options for pregnancy prevention by HIV-positive women are insufficient: condoms are not always available or acceptable, and other options are limited by affordability, availability or efficacy. Further, coerced sterilization of women living with HIV is widely reported. Information gaps persist in relation to effectiveness, safety and best practices regarding assisted reproductive technologies. Attention to neonatal outcomes generally outweighs attention to the health of women before, during and after pregnancy. Access to safe abortion and post-abortion care services, which are critical to women’s ability to fulfill their sexual and reproductive rights, are often curtailed. There is inadequate attention to HIV-positive sex workers, injecting drug users and adolescents. The many challenges that women living with HIV encounter in their interactions with sexual and reproductive health services shape their pregnancy decisions. It is critical that HIV-positive women be more involved in the design and implementation of research, policies and programs related to their pregnancy-related needs and rights.

Résumé

Malgré le nombre croissant de femmes vivant avec le VIH et touchées par ce virus, la recherche, les politiques et les programmes accordent encore trop peu d’attention à leurs besoins, leurs droits, leurs décisions et leurs désirs relatifs à la grossesse. Nous avons analysé les publications pour vérifier l’état actuel des connaissances et dégager les domaines sur lesquels il convient de se pencher. Il en ressort que les options contraceptives pour la prévention de la grossesse chez les femmes séropositives sont insuffisantes : les préservatifs ne sont pas toujours disponibles ou acceptables, et d’autres choix sont limités du fait de leur coût, leur indisponibilité ou leur inefficacité. De plus, la stérilisation contrainte des femmes vivant avec le VIH est fréquemment rapportée. Des lacunes persistent dans l’information en rapport avec l’efficacité, la sécurité et les meilleures pratiques concernant les technologies de procréation assistée. Les résultats néonatals suscitent en général plus d’attention que la santé des femmes avant, pendant et après la grossesse. L’accès à des services sûrs d’avortement et de post-avortement, déterminant pour permettre aux femmes de jouir de leurs droits génésiques, est souvent réduit. Il faut s’intéresser davantage aux professionnelles du sexe, aux consommatrices de drogues injectables et aux adolescentes séropositives. Les nombreux obstacles que rencontrent les femmes vivant avec le VIH dans leurs relations avec les services de santé génésique façonnent leurs décisions en matière de grossesse. Il est capital que les femmes séropositives participent davantage à la conception et la mise en łuvre de recherches, de politiques et de programmes relatifs à leurs droits et besoins en rapport avec la grossesse.

Resumen

A pesar del creciente número de mujeres que viven con VIH y son afectadas por éste, en las investigaciones, políticas y programas aún no se presta suficiente atención a sus necesidades, derechos, decisiones y deseos con relación al embarazo. Realizamos una revisión de la literatura para determinar el estado actual de conocimiento y destacar las áreas que requieren más atención. Encontramos que las opciones anticonceptivas para la prevención del embarazo en mujeres VIH-positivas no son suficientes: los condones no siempre son accesibles o aceptables y otras opciones están limitadas por su disponibilidad, eficacia o costo. Más aún, se informa un alto índice de esterilización forzada entre mujeres que viven con VIH. Aún existen brechas en la información relacionada con la eficacia, seguridad y mejores prácticas respecto a las tecnologías reproductivas asistidas. Generalmente se presta más atención a los resultados neonatales que a la salud de las mujeres antes, durante y después del embarazo. A menudo se restringe el acceso a los servicios de aborto seguro y atención postaborto, los cuales son esenciales para que las mujeres puedan realizar sus derechos sexuales y reproductivos. No se presta adecuada atención a las trabajadoras sexuales VIH-positivas, usuarias de drogas inyectables y adolescentes. Los numerosos retos que encuentran las mujeres que viven con VIH en sus interacciones con los servicios de salud sexual y reproductiva influyen en sus decisiones respecto al embarazo. Es imperativo que las mujeres VIH-positivas participen más en el diseño y la implementación de investigaciones, políticas y programas relacionados con sus necesidades y derechos referentes al embarazo.

Women constitute nearly 52% of the estimated 32.8 million people living with HIV globally.Citation1 With the advent of antiretroviral therapy and with continued channeling of resources into HIV services, greater numbers of HIV-positive women are living longer, healthier lives. As a result, they must contend with a range of longstanding and new issues affecting their sexual and reproductive health – including their needs, rights and desires related to pregnancy. Despite the number of women living with and affected by HIV, their meaningful participation in research, policy and programmatic decision-making has been limited.

A 2010 conference on “The Pregnancy Intentions of HIV-Positive Women: Forwarding the Research Agenda,” highlighted the needs, rights, decisions and desires of HIV-positive women before, during and after pregnancy. The resulting report underscored the need for further research across a range of topics.Citation2 Building on the body of knowledge presented at the conference, the review of the literature captured in this article summarizes relevant research advances since the conference report was published. Findings are chiefly organized according to four types of pregnancy-related issues: seeking to prevent pregnancy; coerced sterilization; safer pregnancy; and pregnancy termination. A separate section discusses health system interactions, including those relating to HIV testing; integration of services; health worker attitudes; stigma and discrimination; and vulnerable populations. Gaps are identified in the peer-reviewed literature, as well as the abstracts, websites, and publications of relevant organizations, and attention is drawn to the ways in which the voices of HIV-positive women have been absent from these pregnancy-related discussions.

Methods

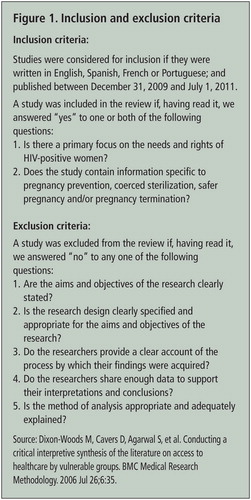

The final reportCitation2 and issue papersCitation3–6 summarizing the literature presented at the above-mentioned conference served as the starting point. A systematic search was conducted of literature published between December 31, 2009, the endpoint of the systematic literature review for the conference, and July 1, 2011. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were used to determine relevant publications within each category ().

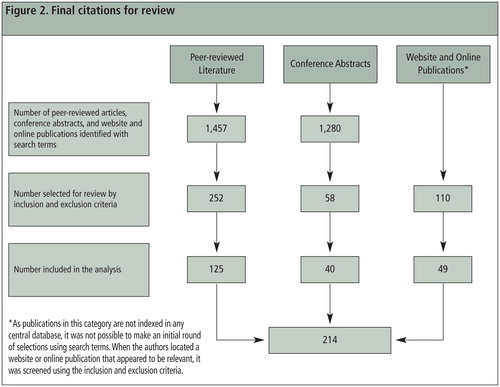

The search strategy drew on various resources in addition to indexes of peer-reviewed journals to capture research findings that were not reflected in the peer-reviewed literature. Specific terms were used to search Pubmed, Web of Science and the abstract databases of the 2010 International AIDS Conference and the 2011 Conference on HIV Pathogenesis, Treatment and Prevention.Footnote* We also scanned the websites and online publications of international and regional (but not national) health-and HIV-related non-governmental organizations, donors and United Nations agencies to identify additional articles of interest.

Two researchers independently assessed a randomly selected 10% of all titles/abstracts retrieved by the search. There was adequate concordance between those chosen for inclusion with a kappa statistic of 0.62. Results were compared and disagreements resolved before the remaining items retrieved were reviewed by a single researcher. The full text of each article was reviewed, and the inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to determine which articles should be part of the analysis. Through this process, 214 articles were selected (). Findings were then summarized and key publications cited.

Findings

Review findings are presented by the types of pregnancy-related intentions and desires that women with HIV might want to fulfill. The review emphasizes the most recent literature on the health, wellbeing and decision-making agency of women themselves, rather than infant and child outcomes. The influence and involvement of women’s partners are discussed only to the extent that they are considered in the articles reviewed. Crosscutting health system issues are addressed separately and specific country examples, as relevant, are highlighted.

HIV-positive women wishing to prevent pregnancy

The ability of a woman to prevent unintended pregnancy is a key element of her sexual and reproductive rights regardless of HIV serostatus. For many women globally, unmet need for contraception persists, particularly in resource-poor settings,Citation7,8 and the rate of unplanned pregnancies is high.Citation9 Emergency contraception in particular is still not widely available in many countries, often because it is not registered despite being included in the World Health Organization (WHO) List of Essential Medicines.Citation10 This literature review identified three key methods used by HIV-positive women wishing to prevent pregnancy: hormonal contraception, condoms and microbicides.

The role of hormonal contraception in pregnancy prevention for HIV-positive women is unclear because there are unanswered questions about its interactions with HIV. The most recent WHO guidelines do not classify HIV infection or the use of antiretroviral drugs as contraindications for hormonal contraception in terms of either HIV transmissibility to sexual partners or disease progression.Citation11 Recent research in seven African countries, however, found that use of the injectable hormonal contraception Depo-Provera by women in HIV-serodiscordant couples almost doubled the likelihood of infection in the HIV-negative partner, irrespective of which partner was initially HIV-positive.Citation12 Both oral and injectable contraceptives were associated with a higher risk of transmission, but the subgroup analysis was statistically significant only for women using injectable forms. This finding may have important implications for women who live in resource-poor settings and have limited access to other forms of contraception.

Other studies, however, have not found an association between the use of hormonal contraceptives and HIV transmissibility.Citation13 In light of this discrepancy, WHO convened a technical consultation in early 2012 to discuss the validity of research to date on hormonal contraception and HIV acquisition and transmission, specifically with respect to the Medical Eligibility Criteria. After extensive debate, WHO’s recommendations for the use of Depo-Provera and other forms of hormonal contraception remain unchanged: there are no restrictions on the use of hormonal contraception by women living with HIV or those at high risk of HIV. Still, the Medical Eligibility Criteria now clarify that “women using progestogen-only injectable contraception should be strongly advised to also always use condoms, male or female, and other HIV preventive measures,” while further research on the relationship between hormonal contraception and HIV proceeds.Citation14 Adequately powered, longitudinal studies that directly assess the relationship between hormonal contraception and HIV acquisition, transmission and progression will be needed to provide conclusive evidence in this regard.Citation15

Two other unresolved questions are whether some antiretroviral drugs make hormonal contraceptives less effective at preventing pregnancy, and whether hormonal contraceptives make antiretrovirals less effective against HIV. In light of the first risk, WHO states that “if a woman on antiretroviral treatment decides to initiate or continue hormonal contraceptive use, the consistent use of condoms is recommended.”Citation11 Furthermore, Rifampin and some other medications used to treat common opportunistic and co-infections in people living with HIV are widely recognized to alter levels of circulating hormonal contraceptives.Citation11 In sum, the use of hormonal contraception by HIV-positive women remains an area of controversy and concern, especially as more women are accessing antiretroviral therapy.

Condoms continue to be the only widely accessible and reliable method of “dual protection,” simultaneously preventing pregnancy and HIV transmission between HIV-positive women and their sexual partners. Acceptability of condoms varies among populations for a number of reasons,Citation16 including availability of alternative contraceptive options, personal preference,Citation17 partner preference and ability to negotiate the use of condoms or other contraceptives (particularly for vulnerable populations such as sex workers).Citation18,19 Social and cultural implications of condom use such as trust and mistrust also influence uptake. As noted by Persson and colleagues, decisions to have unprotected sex are not based solely on calculations of risk, “but are shaped by complex emotions and relationship priorities.”Citation20

Some research has sought to illuminate key factors affecting condom use among HIV serodiscordant couples. Studies have documented variable patterns of condom use by serodiscordant couples in relation to whether or not the positive partner has disclosed his/her HIV status. For example, a study in Europe found that having an HIV-positive partner who had disclosed was associated with reduced condom use.Citation21 In Kenya, recent qualitative research found that the recognized need for consistent condom use in the context of serodiscordance affected sexual behaviors: it decreased the couple’s level of sexual activity and was cited as a reason for seeking concurrent sexual relationships.Citation22 Despite earlier work in this realm, new research is needed to determine the potential role of disclosure of HIV-positive status as a determinant of condom use within HIV-serodiscordant couples.

It is important to develop and make available other acceptable female-controlled and dual protection contraceptive methods.Citation23 Studies have validated the acceptability of the female condom, the only female-controlled approach to dual contraception proven to be effective. However, despite advocacy efforts highlighting the unmet need for readily accessible and acceptable female contraception, particularly the female condom, its availability remains limited.Citation24–26

Some research has explored the effectiveness of the diaphragm and other cervical barriers in conjunction with microbicides to jointly prevent pregnancy and HIV acquisition,Citation27–29 but the potential for a microbicide to reduce the risk of transmission from HIV-positive women to their HIV-negative partners while also preventing pregnancy has not been investigated.Citation30,31 Despite studies documenting vaginal drying practices in southern Africa,Citation32,33 the acceptability of gel-based microbicides used alone or in combination with cervical barriers has largely been supported by research.Citation32–34 An intra-vaginal ring that would function as both a contraceptive and microbicidal agent is also under development as an alternative to barrier methods and dual-action microbicides, with the advantage that such a device can remain in place inconspicuously over extended periods of time and during multiple sexual encounters.Citation35

Despite disappointing results from recent microbicide trials, it is generally agreed that the search for an effective dual-acting microbicide should continue. WHO and HIV-related organizations have advocated for continued attention to clinical equipoise, increased transparency and the involvement of HIV-positive women in microbicide research – not only as study participants, but as members of study design, implementation and oversight teams.Citation36–39 In the meantime, HIV-positive women who wish to prevent pregnancy with non-barrier methods can consider use of different types of contraception, including intrauterine devices or sterilization depending on their desire for reversible or non-reversible methods.

Coerced sterilization

As reflected in the literature, pregnancy prevention for HIV-positive women may also occur because of coerced sterilization. Coerced sterilization refers to the act of female sterilization without consent in health care settings. This violation of human rights typically occurs when women, especially those who are poor or socially excluded, seek other health services such as abortion, caesarean deliveries, the prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission (PMTCT) or cervical cancer screening.Citation25,40–42 Those health services may be rendered on the condition that a woman be sterilized, or sterilization may simply be performed without the woman’s knowledge.

Coerced sterilization is not unique to HIV-positive women, but evidence suggests that some women are sterilized against their will as a result of their HIV serostatus. One study explored cases of sterilization without informed consent in Namibia,Citation43 and a study conducted in Brazil found that health care providers played a significant role in determining whether HIV-positive women were sterilized after delivery.Citation44 It is possible that coerced sterilization will ultimately drive women away from needed health care services, in some cases as a result of having had this experience and in other cases out of fear of it occurring.

Advocacy campaigns spearheaded by the International Community of Women Living with HIV/AIDS have called attention to instances of coerced sterilization of HIV-positive women in Namibia,Citation43,45 South Africa,Citation46 Thailand,Citation47,48 Chile,Citation49,50 MexicoCitation51,52 and Jamaica.Citation53 A range of organizations, including groups of people living with HIV, have released statements and reports raising awareness and condemning the coerced sterilization of HIV-positive women. In 2010, three HIV-positive women received substantial international attention for filing suit in the High Court of Namibia in response to being sterilized without consent at public health facilities.Citation54 In that same year, an HIV-positive Chilean woman, with legal support from the Center for Reproductive Rights and Vivo Positivo, filed a complaint against the Chilean government in the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, claiming she was sterilized without her consent immediately after delivery. To our knowledge, the case is still pending as of this writing.Citation50 In 2011, the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics released updated female contraceptive sterilization guidelines that recognize coerced sterilization as an act of “violence against women.”Citation55

Safer pregnancy

Desire for pregnancy

Many women desire children, regardless of their HIV status. While at least one study has found that some HIV-positive women are less likely than their HIV-negative peers to desire pregnancy,Citation56 research from Brazil, Uganda and Zimbabwe indicates that pregnancy desires may not vary by HIV serostatus.Citation44,57,58 Enhanced access to antiretroviral therapy can enable HIV-positive women to better realize their sexual and reproductive health and rights.Citation59 Although research suggests that neither time on antiretrovirals nor antiretroviral use itself is an important determinant of pregnancy desire,Citation56,60,61 a study conducted in several sub-Saharan African countries showed that antiretroviral use is associated with significantly higher pregnancy rates.Citation62

An HIV-positive woman’s desire to become pregnant appears to be influenced by a complex interconnected array of factors, with individual circumstances contributing to different outcomes in different settings. In India, for example, the desire for a male child, deaths of previous children, family size norms and cultural barriers to pregnancy termination were found to be motivating factors for having a child.Citation63 In Fiji, Papua New Guinea and Botswana the cultural obligation to fulfill the duty of motherhood was a driver of pregnancy intent.Citation64,65 In South Africa,Citation56,60 UgandaCitation66 and Zimbabwe,Citation67 younger age and stable relationship status were associated with pregnancy desire. Finally, not having a child with one’s current partner was an important reason for pregnancy desire in Brazil.Citation44

Partners’ desires to have children were also noted to be important determinants of pregnancy desire in Botswana,Citation68 Uganda,Citation69 and the United States,Citation70 highlighting the need to understand the best ways in which partners can be engaged to support the sexual and reproductive health and rights of HIV-positive women. In many cases, desires for motherhood were found to override the fear of horizontal and/or vertical transmission.Citation71–74

Emerging research regarding safer pregnancy and adolescents highlights important issues. For example, though fewer HIV-positive adolescents may desire pregnancy than their peers in some contexts,Citation75 it is recognized that some adolescents do not routinely use condoms because they want children.Citation76 In Brazil, the median ages of sexual debut and first pregnancy were found to be similar for HIV-positive adolescents who were vertically infected and HIV-negative adolescents.Citation77 However, a study in Uganda found that harsh judgment of HIV-positive adolescents who become pregnant may have encouraged some HIV-positive adolescents to avoid pregnancy even if this was not their wish.Citation78

Given the demonstrated importance of a range of factors in women’s lives for determining pregnancy intentions, any differences in pregnancy desires between women living with HIV and HIV-negative women cannot be assumed to be attributable to HIV status.

Fertility and assisted reproductive technologies

There is some evidence that HIV affects fertility.Citation79–83 A study using Demographic and Health Survey data in Kenya found that HIV-positive women were 40% less likely to have had a recent birth compared to HIV-negative women with similar background characteristics. This could be a result of reduced fecundity, the reproductive choices of HIV-positive women or a combination of these and other unknown factors.Citation81

A study of couples utilizing assisted reproductive technology found that women in couples with at least one HIV-positive partner experienced longer time intervals before getting pregnant than women in HIV-negative couples. Although pregnancy rates for serodiscordant couples did not vary with the sex of the HIV-positive partner, when both partners were HIV-positive, more assisted reproductive cycles were unsuccessful and, consequently, pregnancy rates were lower than they were for age-matched control subjects.Citation84

Lower fertility might be mitigated by increasing the availability, accessibility, acceptability and quality of assisted reproductive technologies. Many HIV-positive women face economic and legal barriers to accessing the technology necessary for fulfilling their desire for pregnancy. Examples include significant financial barriers in Kenya;Citation85 government prohibition of assisted reproductive technology for HIV serodiscordant couples in Vietnam;Citation86 and the exclusion of assisted reproductive technology from national strategic plans for HIV in eight countries in Latin America.Citation87 In the absence of access to assisted reproductive technologies, serodiscordant couples continue to pursue pregnancy despite the risk of HIV transmission. In Kenya, for example, pregnancy has been associated with an increased risk of HIV seroconversion.Citation88 While the rate of transmission within serodiscordant couples in precise conditions is very low, the provision of assisted reproductive technology is still critical for enabling HIV-positive women to safely become pregnant.Citation89 Serodiscordant couples using assisted reproductive technologies still experience anxiety about the risk of HIV transmission, and about their own potential mortality due to HIV, even as they express excitement about their pregnancies.Citation90

Safer conception

For women in serodiscordant partnerships, an important component of safely becoming pregnant is reducing the risk of horizontal HIV transmission within the relationship. Peri-conception pre-exposure prophylaxis has substantial potential in this regard.Citation91,92 Two recent randomized studies in Africa found that daily antiretroviral treatment can reduce the risk of HIV infection among heterosexuals engaging in high-risk sexual behavior. Both studies documented greater than 60% reduction in HIV transmission among serodiscordant couples when uninfected partners took antiretroviral regimens.Citation93,94 Despite the potential of pre-exposure prophylaxis and other assisted reproductive technologies, however, their availability remains limited, particularly in resource-poor settings, and their acceptability unknown.

Attention to women’s health during pregnancy

The majority of studies of HIV-positive pregnant women attempt to better understand the relationship between HIV, antiretroviral therapy and neonatal outcomes such as risk for spontaneous abortion, low birth weight, preterm birth,Citation95 neonatal mortality and HIV transmission. When studies evaluate pregnant women’s CD4 cell counts, this information is often reported only in relation to the apparent effect on the health of the fetus, with the health status of women living with HIV not recognized as a matter of concern.Citation96 Some research has explored biological aspects of safer pregnancy for HIV-positive women and their babies such as the suitability of a lopinavir/ritonavir tablet as opposed to soft gel during pregnancy;Citation97 the potential for raltegravir to be added to PMTCT regimens;Citation98 optimal regimens for PMTCT including the efficacy of protease inhibitor-based combinations;Citation99 and antiretroviral resistance among both antiretroviral-naïve and-experienced pregnant women.Citation100 Additionally, several studies have explored the influence of other factors such as poverty,Citation101–104 psychosocial support for pregnant womenCitation105–107 and their families,Citation108,109 and violenceCitation102 on women’s ability to access a range of available services.

Preventing vertical transmission

Successful strategies to further decrease vertical HIV transmission via increased adherence to antiretroviral regimens and adoption of different service delivery models have been documented.Citation110 Government, donor and United Nations agencies’ work related to HIV and pregnancy has focused on increasing access to prophylactic antiretroviral drugs and adherence to health service programs to “eliminate” vertical transmission.Citation111–119 However, concerns exist in relation to a range of programmatic efforts intended to reduce vertical transmission. Much of the research on antenatal HIV testing, for example, is related to increasing access to treatment in order to reduce the risk of vertical transmission, with limited attention to maternal health, management of the woman’s HIV infection in the perinatal period or her sustained access to antiretroviral therapy.Citation120–122

Several studies in low-income settings have examined health system capacity to provide more complex drug regimes in PMTCT programs and have documented successful transitions from single-dose nevirapine to multi-drug prophylactic antiretroviral regimens.Citation123,124 Moreover, recognizing the difficulty of accessing CD4 count testing in these contexts, some researchers have called for a “test and treat” approach, especially for pregnant women, whereby, once diagnosed with HIV, a woman would be initiated on lifelong antiretroviral therapy.Citation125 This strategy raises numerous questions. For example, a study conducted in Australia documents concerns raised by HIV-positive women regarding drug toxicity and potential harmful effects on their children’s health.Citation126 This research highlights the importance of counseling and continued support for HIV-positive women as they navigate complex biomedical decisions.

Three studies from high-income countries where women received PMTCT interventions explored the association between vaginal births and different outcomes among HIV-positive women. Azria and colleagues found that HIV-positive women were similar to HIV-negative women with respect to mean birth weight, simple or complex perineal laceration rates, and neonatal outcomes. Furthermore, no cases of vertical HIV transmission were reported.Citation127 In a study by Islam and colleagues, there were also no cases of vertical transmission among vaginal births.Citation128 A systematic review of the literature on the role of elective caesarean delivery concluded that the benefits of elective caesarean delivery with respect to vertical transmission continue to outweigh the risks, but noted the need for further research.Citation129

In 2010, formal revisions to WHO guidelines on the prevention of vertical HIV transmission changed the threshold for initiation of lifelong antiretroviral therapy among pregnant women with HIV, called for earlier initiation of antiretroviral prophylaxis among HIV-positive pregnant women who are not eligible for lifelong antiretroviral therapy, and provided additional guidance with respect to breastfeeding. Several concerns were expressed regarding how best to operationalize the latest revisions.Citation130–132

Studies have since documented challenges with respect to breastfeeding in South Africa,Citation133 UgandaCitation134 and Kenya,Citation135,136 resulting in mixed feeding and higher transmission of HIV. Nipple shield devices to decrease breastfeeding-related HIV transmission have been shown to be acceptable but are still in effectiveness trials.Citation137 Evidence suggests that mastitis heightens viral loads in breast milk, thereby increasing vertical transmission,Citation138 and ongoing research is assessing other factors that influence HIV transmission via breast milk.Citation139,140

Research has supported the strategy of involving male partners in antenatal services as a means of preventing vertical HIV transmission,Citation141–143 and non-governmental organizationsCitation144–146 and United Nations agenciesCitation147 have advocated for this approach. PMTCT services have successfully been used as an entry point for promoting male involvement in antenatal services more broadly. Clinic invitations for male participation and couples-only counseling effectively involve men in some settings,Citation148 but several studies have noted resistance from male partners to be tested for HIV even after their female partners test positive.Citation149 In spite of a substantial increase in research exploring male engagement, questions remain as to how engaging men can and will improve services for HIV-positive women. Of concern, for example, is one study that found that Kenyan men influenced women to default from PMTCT programs.Citation150

HIV-positive women wishing to terminate pregnancy

For all women, the ability to safely terminate a pregnancy depends in part on the legal status of abortion where they live, as this influences whether services are clandestine and/or potentially unsafe. Furthermore, while post-abortion care can be life-saving for women who experience spontaneous abortion or for those whose only option is unsafe abortion, accessing post-abortion care, too, can pose significant problems in countries where abortion is restricted, banned or criminalized. HIV-positive women face particular unsafe abortion-related risks, and these risks are largely not addressed in the peer-reviewed literature.

Although evidence is still limited, studies are increasingly exploring the relationship between knowledge of HIV status and pregnancy termination. Two studies in Vietnam concluded that awareness of HIV-positive status was related to an increased likelihood of having an induced abortion.Citation151,152 In contrast, studies in South Africa and Brazil found that socio-economic hardship and poor living conditions at the time of pregnancy were considered more important reasons to choose to abort than HIV status.Citation153–155 A study in Italy identified a range of factors contributing to HIV-positive women’s decision to terminate a pregnancy such as unplanned pregnancy, previous pregnancies, and disease progression, but found no association between pregnancy termination and HIV status.Citation156

The International AIDS Conference did not dedicate a session to abortion until 2010. The occurrence of the session was encouraging, but the highly politicized nature of the abortion debate necessitates deliberate and sustained attention to the links with HIV at the global level. Health-related non-governmental organizations and the United Nations have shown uneven support for this issue.Citation157 For example, recent WHO publications on unsafe abortion,Citation158 abortion care in South AfricaCitation159 and the induction of laborCitation160 do not include any information specific to HIV-positive women. However, a collaborative publication by WHO, UNICEF, the United Nations Population Fund and the World Bank on packages of interventions for maternal, newborn and child health provides exemplary attention to the health and care of HIV-positive women, including access to safe abortion services.Citation161

Interactions with the health system

Across the topics explored thus far in this review, the experiences of HIV-positive women as they interact with the health system shape their sexual and reproductive decision-making processes and often influence women’s ability to achieve desired outcomes. This section discusses HIV-positive women’s interactions with the health system in relation to HIV testing, integration of services, health worker attitudes, and stigma, discrimination and legal barriers both in general and with specific attention to key populations. In all of these areas, the experiences and perspectives of HIV-positive women are often under-represented in the research.

HIV testing

The global policy shift from voluntary counseling and testing for HIV to provider-initiated HIV testing and counseling within the health system has led to large increases in the number of women being tested for HIV, mostly in the context of antenatal care. When WHO published global guidance on this issue in 2007, many researchers highlighted potential pitfalls related to provider-initiated HIV testing and counseling. However, there has been little attention since that time to the ways in which women’s experiences and pregnancy intentions have been affected by the policy change, with studies largely focusing instead on the potential PMTCT benefits. Some researchers have begun to recognize that pregnant women, compared to non-pregnant women and to men, are disproportionately tested under provider-initiated testing, and that the experience can present additional responsibilities and challenges.Citation162–164 Additionally, while several studies document high levels of acceptability with respect to provider-initiated HIV testing and counseling,Citation165,166 a study from Ethiopia noted that despite three-quarters of the study population reporting satisfaction with testing services, 21% of women did not know why they were offered HIV testing during pregnancy.Citation165 Finally, other studies have begun to assess the effectiveness of linkages between HIV testing and long-term HIV care, treatment and support services.Citation167,168

Some HIV and sexual and reproductive health advocates have continued to analyze and question the shift by international donors toward provider-initiated HIV testing and counseling.Citation169 Advocacy networks have drawn attention to the fact that provider-initiated HIV testing and counseling during pregnancy can be problematic, given women’s heightened vulnerability and reliance upon the health care system at that time.Citation170 Despite anecdotal evidence of drawbacks of provider-initiated HIV testing and counseling, particularly with respect to the lack of appropriate counseling, research findings remain limited.

Integration of services

Integration of services, if appropriately implemented, may alleviate some of the challenges to women’s ability to exercise their sexual and reproductive health and rights.Citation171,172 Peer-reviewed literature suggests that current efforts to combine services across a health system focus on adding a specific HIV service to a specific reproductive health service (e.g., introducing HIV testing into antenatal care services) or vice versa (e.g., introducing family planning services into post-test HIV counseling). There are insufficient attempts to critically study and adopt lessons from other health systems efforts in regard to how integration can best be carried out, or to understand, incorporate and respond to the experiences reported by women themselves.Citation173–175 Consequently, many service integration efforts have ignored the constraints of illiteracy and of gender norms that may pose challenges for women’s autonomous decision-making. They have also not shown sufficient concern for women’s sexual and reproductive health as distinct from the potential for HIV transmission to partners or children. Several organizations have devoted resources to researching and advancing the concept of family planning and HIV service integration,Citation115,147,176–180 but there are still no clear-cut, context-specific models or optimal strategies to link or integrate services which adequately respond to the needs of HIV-positive women, particularly in the context of various donor priorities.Citation181

Hence the rubric of integration continues to encompass a wide range of activities and often lacks the specificity required to ascertain which “integrated services” are being delivered. Integrating sexual and reproductive health services with HIV services is not the only objective; there are also efforts to incorporate tuberculosis services,Citation182 services for survivors of gender-based violenceCitation183 and primary health care more generally. Additional research is required on the ways in which health care services, human resources and sufficient technical capacity can be linked or integrated to provide truly comprehensive care.

There is a need for more research on how sexual and reproductive health services themselves can best be integrated. In addition, different models of integrating HIV treatment, care and support with these services, as well as with other areas of health care, may need to be tested so as to improve the health and well-being of HIV-positive women.Citation184

Health worker attitudes

There is continued documentation in the peer-reviewed literature of negative provider attitudes towards HIV-positive women who wish to become pregnant.Citation185,186 Health care providers can be an important source of information and support regarding sexual and reproductive health, and have an essential role in helping women identify contraceptive options that fit their lives. Nevertheless, health workers in Vietnam,Citation187 Thailand,Citation48 Jamaica,Citation53 Ukraine,Citation188 Botswana,Citation189 Zambia, Mexico,Citation52 Swaziland,Citation120 South Africa,Citation190,191 CanadaCitation192 and MozambiqueCitation193 have been found to have negative attitudes about pregnancy among HIV-positive women. This sometimes results in advice to abstain from sex, pressure to abort current pregnancies or refusal of care. Indeed, some Indian women and Kenyan women reported not attending antenatal care or avoiding hospitals at the time of delivery because they perceived such high levels of stigma, discrimination and even hostility.Citation194,195

Studies in BrazilCitation196 and the United StatesCitation197–200 found that many HIV-positive women want to discuss their sexual and reproductive plans with their health care providers, but do not feel comfortable doing so. In Brazil, conversations between health workers and HIV-positive women about fertility desires were found to have been initiated more often by the women themselves.Citation44 Despite continued advances in many aspects of the treatment and care of women living with HIV, health care providers’ attitudes may still negatively impact the care that HIV-positive women seek out or receive.

The knowledge base about how best to address and support the sexual and reproductive health of HIV-positive women has evolved rapidly, and new information has not yet been fully incorporated into published advice and training materials for health workers. This can lead to the provision of inappropriate advice to HIV-positive women,Citation201 for example, regarding potential drug interactions or pre-exposure prophylaxis. Improving health worker knowledge and attitudes through training and mentoring with the participation of HIV-positive women has been found to significantly improve performance, particularly in relation to the frequency of sexual and reproductive health discussions between health workers and HIV-positive women as well as in relation to confidentiality.Citation187 Non-governmental organizations have developed educational materials and training curricula on HIV and pregnancy for health workers in different contexts in order to address stigma in health settings, but these efforts have yet to be brought to scale.

Stigma, discrimination and legal barriers

Stigma manifested by partners, families, the community and the health system directly informs the specific considerations of women living with HIV who are determining or actively pursuing their pregnancy desires. Stigma has been shown to operate differently in different contexts. It may encourage desires for pregnancy when childbearing fulfills a social role or conceals a positive HIV status,Citation202 while discouraging pregnancy when a community predominantly finds it inappropriate or “irresponsible” for women living with HIV to become pregnant.Citation203 Furthermore, fear of potential stigma has been shown to complicate women’s decisions about whether to disclose their HIV status to their partners, families and communities, especially in the context of pregnancy.Citation204

A recent study documented laws and pending laws that criminalize HIV transmission and exposure in parts of Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean. The study also noted that existing laws in Europe and North America were increasingly being used to prosecute people for HIV transmission, sometimes with calls for mandatory testing of pregnant women as well as non-consensual partner disclosure by health workers.Citation205 The impact of criminalization and associated laws and penalties on the willingness of HIV-positive women to become pregnant, carry their pregnancies to term, abort if they so choose, and engage with the health system more generally is an important area for investigation. Women’s health and HIV advocacy organizations,Citation206 in addition to UNAIDS,Citation207 have drawn attention to the rampant discrimination and human rights violations these laws express and engender, as well as to the potential negative health effects, but substantive research is still needed on the consequences of criminalization, discriminatory laws, and the best ways those consequences can be addressed within and outside of the health sector.

Attention to key populations

Stigma and discrimination are especially relevant to the needs, desires and rights of key populations as they affect pregnancy intentions. Despite recent attention to a wider range of groups in the HIV literature, the extent to which this literature engages with the pregnancy-related intentions of women who fall within marginalized groups remains limited at best. Research efforts are, however, increasingly exploring the sexual and reproductive health needs of key populations including sex workers and injecting drug users. There has also been more interest in the influence of the partners of marginalized women, with studies again including sex workersCitation208 and injecting drug users,Citation209,210 but the literature is extremely limited in this area.

The 2010 International AIDS Conference abstracts, in addition to giving attention to sex workers, injecting drug users and adolescents in most thematic areas, also consider the wide-ranging vulnerabilities of other marginalized groups including refugees and asylum seekers; widows; migrants and mobile populations; lesbian, bisexual, transsexual, transgender and intersex populations; indigenous peoples; those in conflict or post-conflict settings; incarcerated populations; rural populations; and people with disabilities. Yet the abstracts show a predominant concern with HIV prevention, testing and treatment among these populations, with little thought given to their sexual and reproductive health and rights. There is almost no examination of how to support fulfillment of their pregnancy intentions. HIV advocacy organizations, such as the Global Network of People Living with HIV/AIDS, have specifically called for advancing the sexual and reproductive health and rights of injecting drug users, sex workers, HIV serodiscordant couples and migrants.Citation37

Furthermore, there is growing recognition of the need to address the sexual and reproductive health and rights of HIV-positive adolescents, some of whom have been living with HIV from birth.Citation179,180,211–213 Most of the literature on adolescents focuses on preventing HIV infection, with little consideration of the additional challenges faced by these young people in negotiating their serostatus and healthfully exploring their sexuality, although this is beginning to change.Citation214,215 One study in Canada explored the complexities of disclosure, fear of rejection, negotiating safe sexual relationships, desires to have children and changes in risk perception over time among adolescents. The study highlighted the need for additional qualitative research to further explore the health needs of adolescent women living with HIV, including in particular their pregnancy desires and barriers to fulfilling their wishes.Citation212

Discussion

The body of published research on the pregnancy decisions of HIV-positive women has grown substantially in the past two years. One particular trend in this literature is a shift from initial assumptions that women living with HIV would not want to have children to systematic reviews that document the myriad factors affecting women’s choices related to pregnancy.

The literature also indicates that programmatic efforts to facilitate voluntary pregnancy prevention by HIV-positive women are insufficient: condoms are not always available or acceptable, and other options are limited by cost and lack of availability, as well as by uncertain efficacy. Further, the current literature overlooks the issue of condom use among HIV-seroconcordant couples, either to prevent HIV re-infection or to prevent pregnancy. Meanwhile, despite efforts by non-governmental organizations to document the extent of coerced sterilization, there appears thus far to be no research published which critically evaluates the scope of the problem regionally or globally, let alone illuminates the contributions of health care policies and providers to these abuses.

The complexities of pregnancy desire and some aspects of safer pregnancy and delivery for HIV-positive women have received substantial attention in the literature, but the majority of research remains focused on preventing vertical HIV transmission during pregnancy, delivery and breastfeeding, and on neonatal health outcomes, with no clear focus on acquiring evidence that would further advance the sexual and reproductive health and rights of HIV-positive women. While United Nations agencies, health-related non-governmental organizations and HIV advocacy organizations alike have increasingly identified a need to make assisted reproductive technologies available to HIV-positive women,Citation216 there has been limited dedicated attention to this area. As research protocols are designed and funded, it is critically important that efforts are made to explore technologies and approaches to conception for HIV-positive women, with attention to the ways in which these methods can be made available, accessible and affordable to women in low-and middle-income contexts. Research is also needed to better understand the dynamics of how a woman’s HIV status relates to her desire and ability to terminate her pregnancy. Being able to disaggregate unsafe abortion incidence, morbidity and mortality would shed further light on this issue. The effects on pregnancy desires of laws which criminalize abortion, as well as the effects of other harmful laws and policies, must be elucidated in order to fully understand and respond to the range of service delivery and human rights concerns facing HIV-positive women.

Moreover, attention is required to models of health service delivery that can ensure a continuum of care from the moment of HIV diagnosis onward, with an appropriate constellation of services delivered in an acceptable manner. Although guidance remains limited as to which services to link or bridge to one another and in which contexts, non-governmental organizations have been exploring ways of integrating various services. Even with appropriate services in place, their acceptability and use will continue to be driven by the interactions that women have with the health system. Special consideration should be given to the impacts of integration as they relate to HIV-positive women’s pregnancy desires and pregnancy outcomes, as responses may require a fundamental reconceptualization of how HIV services are currently provided. Further research about how to alter health workers’ discriminatory attitudes towards women living with HIV is also needed.

HIV-positive women who are sex workers, injecting drug users and adolescents are particularly affected by the range of issues raised in this review, and yet remain largely invisible in the current peer-reviewed literature. The apparent lack of published research on the pregnancy needs and desires of HIV-positive female drug users is a telling example.

The issues raised here – desires to have children or avoid having children, agency to realize those desires, safe pregnancy and safe abortion – impact all women, not just HIV-positive women. Researchers must therefore discern on a case-by-case basis when HIV-positive women should be conceptualized as a population facing unique social pressures, vulnerabilities and biomedical concerns, and when it is useful to consider the demographic of women more broadly so as to best understand, advocate for and provide services geared to the sexual and reproductive health and rights of all women.

There is an evident disconnect between the articulated desires of women living with HIV and the apparent assumptions made by many of those who design and implement relevant studies, policies and programs, often with a detrimental effect on how HIV-positive women interact with the health system as they pursue their sexual and reproductive choices.

Conclusions

To fully and holistically address the sexual and reproductive health needs, rights, decisions and desires of HIV-positive women in relation to pregnancy, researchers must adopt a multidisciplinary perspective that explicitly considers when and how HIV-positive women can best be supported. A multidisciplinary perspective is intended here to mean more than a superficial acknowledgment of the interests of different disciplines. The integration of different types of frameworks, methods and analyses is needed to reconcile language differences, epistemological approaches and diverging priorities. Research conducted by investigators from different disciplines, even if testing separate hypotheses, is nonetheless connected and situated within a larger body of knowledge and sphere of influence. Specificity regarding not only which disciplines are combined and how, but the conceptual framework driving the chosen approach, will be important for framing such efforts. Combining methods and disciplines in a single study can answer a broad array of questions (e.g. “why?” as well as “how many?”) with global utility. Embedding such research efforts within their local contexts allows for the use of research results by HIV-positive women, service delivery organizations and policy makers to effect changes in policy and practice.

The only way to ensure context-specific, sensitive and appropriate sexual and reproductive health research, and ultimately to ensure the quality of the policies and programs it aims to inform, is to take into account the vast biomedical, economic, political and societal forces that HIV-positive women must weigh. Most importantly, HIV-positive women must participate in all phases of developing effective research, policies and programs, from conceptualization through implementation. This process has the potential to yield new paradigms that will enable far more HIV-positive women worldwide to voice their concerns, articulate potential solutions and ultimately fully realize their pregnancy decisions.

Notes

* Search criteria for the searches of PubMed, Web of Science and the abstract databases of the 2010 International AIDS Conference and the 2011 Conference on HIV Pathogenesis, Treatment and Prevention can be viewed at http://globalhealth.usc.edu/Home/Research%20And%20Services/Pages/~/media/192A5B2C1AA34C0D8961F0C31344CD74.ashx.

References

- UNAIDS. UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2010. At: http://www.unaids.org/globalreport/documents/20101123_GlobalReport_full_en.pdf Accessed 5 August 2012

- Program on International Health and Human Rights. The pregnancy intentions of HIV-positive women: forwarding the research agenda. 2010; Harvard School of Public Health: BostonAt: http://globalhealth.usc.edu/Home/Research%20And%20Services/Pages/Publications.aspx#MeetingReports Accessed 5 August 2012

- Program on International Health and Human Rights. Issue Paper 1. 2010; Harvard School of Public Health: Boston.

- Program on International Health and Human Rights. Issue Paper 2. 2010; Harvard School of Public Health: Boston.

- Program on International Health and Human Rights. Issue Paper 3. 2010; Harvard School of Public Health: Boston.

- Program on International Health and Human Rights. Issue Paper 4. 2010; Harvard School of Public Health: Boston.

- Wanyenze R, Kindyomunda R, Beyeza J, et al. Uptake of contraceptives and unplanned pregnancies among HIV-infected patients in Uganda. XVIII International AIDS Conference; 2010 July 18–23; Vienna.

- R King, K Khana, S Nakayiwa. “Pregnancy comes accidentally – like it did with me”: reproductive decisions among women on ART and their partners in rural Uganda. BMC Public Health. 11(530): 2011

- Groves AK, Kagee A, Maman S, et al. Associations between partner violence and symptoms of anxiety and depression among pregnant women in Durban, South Africa and the implications for PMTCT. XVIII International AIDS Conference; 2010 July 18–23; Vienna.

- World Health Organization. WHO Model List of Essential Medicines. 2011. At: www.who.int/medicines/publications/essentialmedicines/en/ Accessed 5 August 2012

- World Health Organization. Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use: fourth edition. 2009. At: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241563888_eng.pdf Accessed 5 August 2012

- Heffron R, Donnell D, Rees H, et al. Hormonal contraceptive use and risk of HIV-1 transmission: a prospective cohort analysis. XVIII International AIDS Conference; 2010 July 18–23; Vienna.

- E Stringer, E Antonsen. Hormonal contraception and HIV disease progression. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 47(7): 2008 Oct 1; 945–951.

- World Health Organization. Hormonal contraception and HIV: technical statement. 2012. At: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2012/WHO_RHR_12.08_eng.pdf Accessed 5 August 2012

- CA Blish, JM Baeten. Hormonal contraception and HIV-1 transmission. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 65(3): 2011 Mar; 302–307.

- C Kelly, M Lohan, F Alderdice. Negotiation of risk in sexual relationships and reproductive decision-making amongst HIV sero-different couples. Culture, Health and Sexuality. 13(7): 2011 Aug; 815–827.

- Samarina A, Whiteman M, Kissin D, et al. Access to modern contraception among HIV-infected women receiving clinical care. XVIII International AIDS Conference; 2010 July 18–23; Vienna.

- RTI International. Study: negotiation skills training shown to increase condom use, reduce heterosexual HIV transmission in South Africa. 2010. At: http://www.rti.org/newsroom/news.cfm?nav=821&objectid=5F3D6C18-C478-7BA4-5A7CF11AF0850C14 Accessed 5 August 2012

- RTI International. A comparison of four condom-use measures in predicting pregnancy, cervical STI and HIV incidence among Zimbabwean women. 2010. At: http://www.rti.org/publications/rtipress.cfm?pub=15085 Accessed 5 August 2012

- A Persson. Reflections on the Swiss Consensus Statement in the context of qualitative interviews with heterosexuals living with HIV. AIDS Care. 22(12): 2010 Dec; 1487–1492.

- C Nostlinger, S Niderost, R Woo. Mirror, mirror on the wall: the face of HIV-positive women in Europe today. AIDS Care. 22(8): 2010 Aug; 919–926.

- Marx G, Kinoti F, Kiarie J, et al. Barriers and motives for dual contraception use by HIV-1 serodiscordant couples in Nairobi, Kenya. XVIII International AIDS Conference; 2010 July 18–23; Vienna.

- HM Marlow, EE Tolley, R Kohli. Sexual communication among married couples in the context of a microbicide clinical trial and acceptability study in Pune, India. Culture, Health and Sexuality. 12(8): 2010 Nov; 899–912.

- OXFAM International. Female condoms ignored by donors. 2010. At: http://www.oxfam.org/en/pressroom/pressrelease/2010-07-21/female-condoms-ignored-donors Accessed 5 August 2012

- International Community of Women with HIV/AIDS. Press statement: ICW Eastern Africa and ICW Southern Africa sexual and reproductive health and rights priorities. 2010.

- Center for Health and Gender Equity. Female condoms and US foreign assistance: an unfinished imperative for women’s health. 2011. At: http://www.genderhealth.org/files/uploads/prevention_now/publications/unfinishedimperative.pdf Accessed 5 August 2012

- ET Montgomery, C Woodsong, P Musara. An acceptability and safety study of the Duet cervical barrier and gel delivery system in Zimbabwe. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 13: 2010; 30.

- CE von Mollendorf, L Van Damme, JA Moyes. Results of a safety and feasibility study of the diaphragm used with ACIDFORM Gel or K-Y Jelly. Contraception. 81(3): 2010 Mar; 232–239.

- ET Montgomery, A van der Straten, A Chidanyika. The importance of male partner involvement for women’s acceptability and adherence to female-initiated HIV prevention methods in Zimbabwe. AIDS and Behavior. 15(5): 2011 Jul; 959–969.

- S McCormack, G Ramjee, A Kamali. PRO2000 vaginal gel for prevention of HIV-1 infection (Microbicides Development Programme 301): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, parallel-group trial. The Lancet. 376(9749): 2010 Oct 16; 1329–1337.

- A Kamali, H Byomire, C Muwonge. A randomised placebo-controlled safety and acceptability trial of PRO 2000 vaginal microbicide gel in sexually active women in Uganda. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 86(3): 2010 Jun; 222–226.

- M Gafos, M Mzimela, S Sukazi. Intravaginal insertion in KwaZulu-Natal: sexual practices and preferences in the context of microbicide gel use. Culture, Health and Sexuality. 12(8): 2010 Nov; 929–942.

- J Stadler, E Saethre. Blockage and flow: intimate experiences of condoms and microbicides in a South African clinical trial. Culture, Health and Sexuality. 13(1): 2011 Jan; 31–44.

- AE Tanner, JD Fortenberry, GD Zimet. Young women’s use of a microbicide surrogate: the complex influence of relationship characteristics and perceived male partners’ evaluations. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 39(3): 2010 Jun; 735–747.

- Paddock M. 2 for 1: developing intra-vaginal microbicidal/contraceptive rings. XVIII International AIDS Conference; 2010 July 18–23; Vienna.

- ATHENA Network and The AIDS Legal Network. Transparency, accountability and feminist science – what next for microbicide trials? 2010. At: http://www.athenanetwork.org/assets/files/microbicide_0131.pdf Accessed 5 August 2012

- Global Network of People living with HIV/AIDS. Sexual and reproductive health and rights documents. At: http://www.gnpplus.net/en/resources/sexual-and-reproductive-health-and-rights Accessed 5 August 2012

- International Council of AIDS Service Organizations. A community-led advocacy agenda for microbicides. 2010. At: http://www.icaso.org/publications/2010/MicrobicidesEN.pdf Accessed 5 August 2012

- World Health Organization. Developing sexual health programmes: a framework for action. 2010. At: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2010/WHO_RHR_HRP_10.22_eng.pdf Accessed 5 August 2012

- International Community of Women with HIV/AIDS. Country Visits. 2010. At: http://www.icwap.org/?p=93 Accessed 5 August 2012

- International Community of Women with HIV/AIDS International Planned Parenthood Federation, Balance. New challenges and opportunities: universal access to reproductive care. 2010. At: http://www.icwlatina.org/icw/imagenes/factsheetregionalingles.pdf Accessed 5 August 2012

- International Community of Women with HIV/AIDS East Africa. Sexual, reproductive and maternal health and rights regional advocacy meeting and policy forum report. 2011. At: http://www.salamandertrust.net/index.php/Resources/Key_Resources_by_other_Women_living_with_HIV/www.icwea.org/Admin/files/SRMHR%20Regional%20Advocacy%20Meeting%20Policy%20Forum%20Report%20Fw.pdf Accessed 14 August 2012

- L Dumba. Namibia: litigating the cases of sterilization without informed consent of HIV-positive women. HIV/AIDS Policy and Law Review. 15(1): 2010 Oct; 50–51.

- Rossi AA, E. Makuch, MY. Burgos, R. Perspectives of Brazilian people living with HIV/AIDS on reproductive desire: access and barriers to treatment. XVIII International AIDS Conference; 2010 July 18–23; Vienna.

- J Gatsi, J Kehler, T Crone. Make it everybody’s business: lessons learned from addressing the coerced sterilization of women living with HIV in Namibia. ATHENA Network and The AIDS Legal Network; 2010. At: http://www.athenanetwork.org/assets/files/Make%20it%20everyone%27s%20business...%20–%20Report.pdf Accessed 5 August 2012

- A Lombard. South Africa: HIV-positive women sterilized against their will. 7 June. 2010; City Press.

- Netjaiboon M, Oumin A. Accessing treatment and reproductive health services for women living with HIV/AIDS who are foreign migrant laborers living in Ranong, Thailand. XVIII International AIDS Conference; 2010 July 18–23; Vienna.

- Talawat S, Phiromchai R, Pantichpakdi P, et al. Monitoring and evaluation of policies and their impact on people living with HIV, affected communities and vulnerable populations. XVIII International AIDS Conference; 2010 July 18–23; Vienna.

- Center for Reproductive Rights. Forcibly sterilized woman files international case against Chile. New York; 2009. At: http://reproductiverights.org/en/press-room/forcibly-sterilized-woman-files-international-case-against-chile Accessed 5 August 2012

- Center for Reproductive Rights, Vivo Positivo. Dignity denied: violations of the rights of HIV-positive women in Chilean health facilities. 2010. At: http://reproductiverights.org/sites/crr.civicactions.net/files/documents/chilereport_FINAL_singlepages.pdf Accessed 5 August 2012

- Population Council. Sexual and reproductive health needs and experiences of (recently) pregnant women living with HIV in Mexico. 2010. At: http://www.popcouncil.org/mediacenter/events/2010PAA/vanDijk.asp Accessed 5 August 2012

- T Kendall. Reproductive rights violations reported by Mexican women with HIV. Health and Human Rights. 11(2): 2009; 77–87.

- Watson P, Crawford J. I am alive! Protecting the SRH and rights of positive women in Jamaica. XVIII International AIDS Conference; 2010 July 18–23; Vienna.

- Center for Reproductive Rights. Demanding rights for HIV-positive women. New York; 2010. At: http://reproductiverights.org/en/feature/demanding-rights-for-hiv-positive-women Accessed 5 August 2012

- International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics. Female contraceptive sterilization. 2011. At: http://www.figo.org/files/figo-corp/FIGO%20-%20Female%20contraceptive%20sterilization.pdf Accessed 5 August 2012

- A Kaida, F Laher, SA Strathdee. Childbearing intentions of HIV-positive women of reproductive age in Soweto, South Africa: the influence of expanding access to HAART in an HIV hyperendemic setting. American Journal of Public Health. 101(2): 2011 Feb; 350–358.

- Kyegonza C, Lubaale YAM. Factors influencing the desire to have children among HIV-positive women in Uganda. XVIII International AIDS Conference; 2010 July 18–23; Vienna.

- N Smee, AK Shetty, L Stranix-Chibanda. Factors associated with repeat pregnancy among women in an area of high HIV prevalence in Zimbabwe. Women’s Health Issues. 21(3): 2011 May-Jun; 222–229.

- S Cliffe, CL Townsend, M Cortina-Borja. Fertility intentions of HIV-infected women in the United Kingdom. AIDS Care. 23(9): 2011 Sep; 1093–1101.

- Schwartz S, Taha TE, Rees H, et al. Fertility intentions by antiretroviral regimen among women in inner-city Johannesburg, South Africa. XVIII International AIDS Conference; 2010 July 18–23; Vienna.

- Revzina N, Whiteman M, Kissin D, et al. Prevalence and determinants of fertility desires among HIV-infected women in St. Petersburg, Russia. XVIII International AIDS Conference; 2010 July 18–23; Vienna.

- L Myer, R Carter, M Katyal. Impact of antiretroviral therapy on incidence of pregnancy among HIV-infected women in Sub-Saharan Africa: A cohort study. PLoS Medicine. 9(7): 2010

- Jadhav S, Darak S, Parchure R, et al. Pregnancies among women with known HIV infection – experiences from a private sector PMTCT project in Pune, Maharashtra, India. XVIII International AIDS Conference; 2010 July 18–23; Vienna.

- Gorman H. Motherhood, reproduction, and treatment: a qualitative study of the experiences of HIV-positive women in the Pacific. XVIII International AIDS Conference; 2010 July 18–23; Vienna.

- RL Upton, EM Dolan. Sterility and stigma in an era of HIV/AIDS: narratives of risk assessment among men and women in Botswana. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 15(1): 2011 Mar; 95–102.

- Ssewankambo F, Nalugwa C, Lutalo I, et al. Pregnancy intention and pregnancy risk behavior among women receiving HIV/AIDS care in Uganda. XVIII International AIDS Conference; 2010 July 18–23; Vienna.

- MK McClellan, R Patel, G Kadzirange. Fertility desires and condom use among HIV-positive women at an antiretroviral roll-out program in Zimbabwe. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 14(2): 2010 Jun; 27–35.

- YM Bah’him, OO Oguntibeju, HA Lewis. Factors associated with pregnancies among HIV-positive women in a prevention of mother-to-child transmission programme. West Indian Medical Journal. 59(4): 2010 Jul; 362–368.

- J Beyeza-Kashesya, AM Ekstrom, F Kaharuza. My partner wants a child: a cross-sectional study of the determinants of the desire for children among mutually disclosed sero-discordant couples receiving care in Uganda. BMC Public Health. 10: 2010; 247.

- JT Gosselin, MV Sauer. Life after HIV: examination of HIV serodiscordant couples’ desire to conceive through assisted reproduction. AIDS and Behavior. 15(2): 2011 Feb; 469–478.

- BL Guthrie, RY Choi, R Bosire. Predicting pregnancy in HIV-1-discordant couples. AIDS and Behavior. 14(5): 2010 Oct; 1066–1071.

- O Awiti Ujiji, AM Ekstrom, F Ilako. “I will not let my HIV status stand in the way.” Decisions on motherhood among women on ART in a slum in Kenya – a qualitative study. BMC Women’s Health. 10: 2010; 13.

- P Kisakye, WO Akena, DK Kaye. Pregnancy decisions among HIV-positive pregnant women in Mulago Hospital, Uganda. Culture, Health and Sexuality. 12(4): 2010 May; 445–454.

- S Finocchario-Kessler, MD Sweat, JK Dariotis. Understanding high fertility desires and intentions among a sample of urban women living with HIV in the United States. AIDS and Behavior. 14(5): 2010 Oct; 1106–1114.

- J Beyeza-Kashesya, F Kaharuza, AM Ekstrom. To use or not to use a condom: a prospective cohort study comparing contraceptive practices among HIV-infected and HIV-negative youth in Uganda. BMC Infectious Diseases. 11: 2011; 144.

- Adipo D, Loos J, Muringi I, et al. “Say no to sex, use condoms… but HOW?” Perceptions, barriers and strategies towards sexual and reproductive health among adolescents living with HIV in Kenya and Uganda. XVIII International AIDS Conference; 2010 July 18–23; Vienna.

- Cruz M, Cardoso C, Joao E, et al. Pregnancy in HIV vertically-infected adolescents: a new generation of HIV-exposed infants. XVIII International AIDS Conference; 2010 July 18–23; Vienna.

- Mbeetah Kazibwe S, Karamagi Y, Suubi R, et al. The needs for SRH services provision to HIV-positive adolescents in Uganda. XVIII International AIDS Conference; 2010 July 18–23; Vienna.

- N Dhont, S Luchters, C Muvunyi. The risk factor profile of women with secondary infertility: an unmatched case-control study in Kigali, Rwanda. BMC Women’s Health. 11: 2011; 32.

- N Dhont, J van de Wijgert, J Vyankandondera. Results of infertility investigations and follow-up among 312 infertile women and their partners in Kigali, Rwanda. Tropical Doctor. 41(2): 2011 Apr; 96–101.

- MA Magadi, AO Agwanda. Investigating the association between HIV/AIDS and recent fertility patterns in Kenya. Social Science and Medicine. 71(2): 2010 Jul; 335–344.

- CO Agboghoroma. Gynaecological and reproductive health issues in HIV-positive women. West African Journal of Medicine. 29(3): 2010 May-Jun; 135–142.

- A Gingelmaier, K Wiedenmann, M Sovric. Consultations of HIV-infected women who wish to become pregnant. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 283(4): 2011 Apr; 893–898.

- P Santulli, V Gayet, P Fauque. HIV-positive patients undertaking ART have longer infertility histories than age-matched control subjects. Fertility and Sterility. 95(2): 2011 Feb; 507–512.

- G Marx, G John-Stewart, R Bosire. Diagnosis of sexually transmitted infections and bacterial vaginosis among HIV-1-infected pregnant women in Nairobi. International Journal of STD and AIDS. 21(8): 2010 Aug; 549–552.

- Khuat O, Ong T, Vu T, et al. Condoms or no condoms? Dilemma of discordant couples. XVIII International AIDS Conference; 2010 July 18–23; Vienna.

- T Kendall. Criminalization of HIV transmission or exposure in eight Latin American countries. HIV/AIDS Policy and Law Review. 15(1): 2010 Oct; 42–44.

- SG Brubaker, EA Bukusi, J Odoyo. Pregnancy and HIV transmission among HIV-discordant couples in a clinical trial in Kisumu, Kenya. HIV Medicine. 12(5): 2011 May; 316–321.

- A Vandermaelen, Y Englert. Human immunodeficiency virus serodiscordant couples on highly active antiretroviral therapies with undetectable viral load: conception by unprotected sexual intercourse or by assisted reproduction techniques?. Human Reproduction. 25(2): 2010 Feb; 374–379.

- FH Azemar, M Daudin, L Bujan. Assisted reproductive technologies for serodiscordant couples: desire for child and pregnancy versus the fact of illness. Gynecologie, Obstetrique and Fertilite. 38(1): 2010 Jan; 58–69.

- L Matthews, J Baeten, C Celum. Periconception pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV transmission: benefits, risks, and challenges to implementation. AIDS. 24(13): 2010; 1975–1982.

- MA Lampe, DK Smith, GJ Anderson. Achieving safe conception in HIV-discordant couples: the potential role of oral preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in the United States. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 204(6): 2011 Jun; 488 e1–488 e8.

- HIV Prevention Trials Network. Initiation of antiretroviral treatment protects uninfected sexual partners from HIV infection. 2011; Washington, DC.

- University of Washington International Clinical Research Center. Pivotal study finds that HIV medications are highly effective as prophylaxis against HIV infection in men and women in Africa. Seattle; July 13, 2011.

- CL Townsend, PA Tookey, ML Newell. Antiretroviral therapy in pregnancy: balancing the risk of preterm delivery with prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission. Antiviral Therapy. 15(5): 2010; 775–783.

- Urueña A, Cecchini DM, Bologna R. Neonatal outcomes after perinatal exposure to HIV-1 in Argentina. XVIII International AIDS Conference; 2010 July 18–23; Vienna.

- Taylor G, Else L, Dickenson L, et al. Comparison of total and unbound lopinavir pharmocokinetics in HIV-infected pregnant women receiving lopinavir/ritonavir soft-gel capsules or tablets. XVIII International AIDS Conference; 2010 July 18–23; Vienna.

- Rosenvinge M, McKeown D, Cormack I, et al. Raltegravir in the prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV: high concentrations demonstrated in newborns. XVIII International AIDS Conference; 2010 July 18–23; Vienna.

- N Briand, L Mandelbrot, S Blanche. Previous antiretroviral therapy for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV: integrating prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission (PMTCT) programmes. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 57(2): 2011; 126–135.

- Bacelar Acioli J, Lins K, Alcantara C, et al. Primary and secondary antiretroviral resistance mutations among HIV-infected pregnant women from Central West Brazil. XVIII International AIDS Conference; 2010 July 18–23; Vienna.

- P Duff, W Kipp, TC Wild. Barriers to accessing highly active antiretroviral therapy by HIV-positive women attending an antenatal clinic in a regional hospital in western Uganda. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 13: 2010; 37.

- S Mepham, Z Zondi, A Mbuyazi. Challenges in PMTCT antiretroviral adherence in northern KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. AIDS Care. 23(6): 2011 Jun; 741–747.

- M Panditrao, S Darak, V Kulkarni. Socio-demographic factors associated with loss to follow-up of HIV-infected women attending a private sector PMTCT program in Maharashtra, India. AIDS Care. 23(5): 2011 May; 593–600.

- A Muchedzi, W Chandisarewa, J Keatinge. Factors associated with access to HIV care and treatment in a prevention of mother to child transmission programme in urban Zimbabwe. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 13: 2010; 38.

- D Futterman, J Shea, M Besser. Mamekhaya: a pilot study combining a cognitive-behavioral intervention and mentor mothers with PMTCT services in South Africa. AIDS Care. 22(9): 2010 Sep; 1093–1100.

- Q Darmont Mde, HS Martins, GA Calvet. [Adherence to prenatal care by HIV-positive women who failed to receive prophylaxis for mother-to-child transmission: social and behavioral factors and healthcare access issues]. Cadernos de Saude Publica. 26(9): 2010 Sep; 1788–1796.

- MJ Rotheram-Borus, L Richter, H Van Rooyen. Project Masihambisane: a cluster randomised controlled trial with peer mentors to improve outcomes for pregnant mothers living with HIV. Trials. 12: 2011; 2.

- TS Betancourt, EJ Abrams, R McBain. Family-centred approaches to the prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 13(Suppl 2): 2010; S2.

- EF Falnes, KM Moland, T Tylleskar. The potential role of mother-in-law in prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV: a mixed methods study from the Kilimanjaro region, northern Tanzania. BMC Public Health. 2011 Jul; 11.

- Humbert R, Vrakking H. Field testing of the Mother-Baby Pack (MBP) design for PMTCT. XVIII International AIDS Conference; 2010 July 18–23; Vienna.

- World Health Organization. Antiretroviral drugs for treating pregnant women and preventing HIV infection in infants: towards universal access. 2010. At: http://www.who.int/entity/hiv/pub/mtct/antiretroviral/en/index.html Accessed 5 August 2012

- UNAIDS. UNAIDS strategy 2011–2015: getting to zero. 2010. At: http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2010/JC2034_UNAIDS_Strategy_en.pdf Accessed 5 August 2012

- United Nations. Report of the UN Secretary-General – Uniting for universal access: towards zero new HIV infections, zero discrimination and zero AIDS-related deaths 2011. At: http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/document/2011/20110331_SG_report_en.pdf Accessed 5 August 2012

- World Health Organization. Universal access to reproductive health: accelerated actions to enhance progress on MDG 5 through advancing target 5B. 2011. At: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2011/WHO_RHR_HRP_11.02_eng.pdf Accessed 5 August 2012

- United Nations Population Fund. We can prevent mothers from dying and babies from becoming infected with HIV. 2010. At: http://www.unfpa.org/webdav/site/global/shared/documents/publications/2011/PMTCT_Business_Case.pdf Accessed 5 August 2012

- United States Agency for International Developement. Two decades of progress: USAID’s child survival and maternal health program. At: http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PDACN044.pdf Accessed 5 August 2012

- United States Agency for International Developement. United in partnership against HIV/AIDS 2010. At: http://transition.usaid.gov/our_work/global_health/aids/Publications/united_in_partnership.pdf Accessed 5 August 2012

- AusAID. New media campaign addresses mother-to-child transmission of HIV and AIDS in Africa. 2011. At: http://www.ausaid.gov.au/HotTopics/Pages/Display.aspx?QID=281 Accessed 5 August 2012

- AusAID. Keeping our commitment: Australia’s support for the HIV response. 2011. At: http://www.ausaid.gov.au/aidissues/health/hivaids/Documents/keepingcommitment-hivresponse.pdf Accessed 5 August 2012

- D Patel, M Cortina-Borja, A De Maria. Factors associated with HIV RNA levels in pregnant women on non-suppressive highly active antiretroviral therapy at conception. Antiviral Therapy. 15(1): 2010; 41–49.