Abstract

Outreach services for vaccination present a useful vehicle to deliver maternal and child health (MCH) care to hard-to-reach women and children. In Laos, uptake of MCH services inversely correlates with distance from a health facility; hence, the concurrent delivery of MCH services during community vaccination outreach has been promoted. Here we assess factors affecting delivery of MCH services during vaccination outreach in six districts of three provinces. We conducted 58 in-depth interviews with representatives of district and provincial health offices, health centre staff and village health volunteers. Vaccination outreach sessions by health centre staff were observed in eight villages, and 12 focus group discussions were held with 120 mothers on their perceptions of these sessions. The regularity and frequency of outreach sessions and the number of integrated vaccination/MCH services varied widely between sites. Availability of external financial and technical support was the major determinant of optimal delivery of integrated services, with implications for future policy. To enable concurrent delivery of a range of MCH services during vaccination outreach, the number of these services should gradually be increased in tandem with additional financial and technical support. At the same time, ways need to be found to ensure remote villages are reached and coverage of children and women receiving services increased, to reduce inequity.

Résumé

Les services mobiles de vaccination constituent un véhicule utile pour apporter des soins de santé maternelle et infantile (SMI) à des femmes et des enfants difficiles à atteindre. Au Laos, le recours aux services de SMI est inversement proportionnel à la distance d'un centre de santé; par conséquent, la prestation de services de SMI pendant les vaccinations dans les communautés a été encouragée. Nous évaluons ici les facteurs influençant les services de SMI pendant les séances de vaccination dans six districts de trois provinces. Nous avons mené 58 entretiens approfondis avec des représentants des bureaux sanitaires provinciaux et des districts, du personnel des centres de santé et des agents sanitaires bénévoles dans les villages. Les séances de vaccination réalisées par le personnel des centres de santé ont été observées dans huit villages et 12 discussions de groupe ont été organisées avec 120 mères sur leur perception de ces séances. La régularité et la fréquence des séances et le nombre de services intégrés de vaccination/SMI variaient largement selon les sites. La disponibilité du soutien financier et technique externe était le principal déterminant d'une prestation optimale des services intégrés, avec des conséquences sur les politiques futures. Pour permettre de dispenser une gamme de services de SMI pendant les séances de vaccination, le nombre de ces services doit progressivement augmenter, parallèlement à une majoration du soutien technique et financier. En même temps, il faut trouver des moyens de desservir les villages éloignés et de relever le taux de femmes et d'enfants bénéficiant de ces services, afin de réduire les inégalités.

Resumen

Los servicios comunitarios de vacunación constituyen un medio útil para prestar servicios de salud materno-infantil (SMI) a mujeres y niños difíciles de alcanzar. En Laos, la aceptación de los servicios de SMI está correlacionada inversamente con la distancia a la unidad de salud; por lo tanto, se ha promovido la prestación concurrente de servicios de SMI durante la vacunación comunitaria. Aquí se evalúan los factores que afectan la prestación de dichos servicios durante la vacunación en seis distritos de tres provincias. Realizamos 58 entrevistas a profundidad con representantes de oficinas de salud distritales y provinciales, personal de centros de salud y voluntarios comunitarios en salud. Se observaron las sesiones de vacunación realizadas por el personal de centros de salud en ocho poblados y se llevaron a cabo 12 discusiones en grupos focales con 120 madres sobre sus percepciones de estas sesiones. La regularidad y frecuencia de las sesiones y el número de servicios integrados de vacunación/SMI variaron extensamente entre los lugares. La disponibilidad de apoyo externo financiero y técnico fue el principal determinante de una prestación óptima de los servicios integrados, con implicaciones para futuras políticas. Para permitir la prestación simultánea de una variedad de servicios de SMI durante las sesiones de vacunación, se debe aumentar gradualmente el número de estos servicios, así como apoyo adicional financiero y técnico. A la vez, se debe encontrar la manera de llegar a los poblados remotos y de aumentar la cobertura de los niños y las mujeres que reciben los servicios, con el fin de disminuir las desigualdades.

Childhood vaccination is an effective, low-cost health intervention that has achieved a considerable reduction in child mortality in low- and middle-income countries.Citation1,2 In countries with insufficiently robust health systems, the use of community outreach sessions, by which public health facility staff travel to a village to vaccinate women and children, has been recommended as a means to ensure high uptake of vaccinations.Citation3,4 Outreach also provides a useful way to concurrently deliver other primary health care interventions, such as micronutrient supplementation or antenatal care to hard-to-reach groups.Citation1,5,6 Criteria for selecting health interventions for integration into the package of outreach services include: the population burden of the condition, cost-effectiveness, availability of required supplies and materials, skills of existing health personnel, and the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention.Citation5 The resulting intervention package must also be tailored to the specific context.Citation7

Country experiences with outreach services, however, have been mixed,Citation8 and there is little evidence on the conditions for their effective delivery, including on the integration of broader maternal and child health (MCH) services (such as antenatal care, vitamin A supplementation, de-worming, family planning) in such programmes.Citation6,9 With this study we sought to gather evidence on the success of recent efforts to strengthen outreach services for integrated child vaccination and maternal and child health in Laos.

Despite improvement in recent decades, maternal, infant and child mortality rates in Laos are amongst the highest in East Asia (maternal mortality 405/100,000, infant mortality 70/1,000 and child mortality 98/1,000). In part, high levels of mortality are due to the low level of coverage of key primary health care interventions, such as antenatal care (ANC), institutional delivery, available emergency obstetric care, post-partum and post-natal care, and vaccinations. For example, nationwide cross-sectional surveys conducted in 2005 and 2006Citation10,11 show that 81% of urban pregnant women had at least one ANC visit during pregnancy vs. 38% of rural women. Respective figures for institutional deliveries were 52% and 10%. Only 56% of women of reproductive age were protected against tetanus, and 40% of urban children aged 12–23 months were fully vaccinated compared to 25% of rural children. These data are partly explained by limited access to services. Laos is a predominantly rural country (70% of the population), with low population density (24 persons/km2), difficult terrain, poor infrastructure, and an under-developed network of health centres and district hospitals.

In 2007, 29% of the population lived more than 10km from the nearest health centre,Citation12 and utilization of facility-based services was very low. Besides the central and specialized hospitals in the capital city Vientiane, there are 5 regional hospitals, 13 provincial hospitals, 127 district hospitals and 750 health centres. The latter are mainly staffed by volunteers hoping to get on the government payroll and derive their income from revolving drug funds, a mechanism by which the government allows them to sell medicines with a profit of 25% above the procurement price. At village level the health system is represented by the Village Health Volunteers (VHVs), who should provide health education, assist in outreach sessions and report morbidity and mortality data. Two such volunteers should be selected in consultation with the villagers and District Health Office, although in practice they are often appointed by the Village Head.

In this context, outreach has long been an important element of the government's vaccination programme, both for periodic mass immunization campaigns and routine vaccinations. While other countries have used mobile clinics or home visits to increase vaccination coverage, the challenging terrain of Laos renders these approaches ineffective.Citation9

In May 2009, the Ministry of Health (MOH) indicated its intention to deliver MCH services in addition to vaccinations at village level through outreach, to foster a positive relationship between communities and health service providers through this extended package of services.Citation13,14 Guidelines were formulated one year later and disseminated to all District and Provincial Health Offices in the country. These guidelines stipulated the following services to be delivered during outreach sessions at village level:

| • | For children: weighing and measuring for nutrition status; vaccination; Vitamin A supplementation and de-worming; health checkups for sick children. | ||||

| • | Maternal care: antenatal care, counselling on prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission; post-partum examination; provision of iron folate to pregnant and post-partum women; post-partum Vitamin A supplementation; newborn assessment. | ||||

| • | Women of reproductive age: tetanus vaccination; family planning; health education. | ||||

While this seemed like a promising approach, success was by no means guaranteed. Laos has a mixed record concerning the delivery of essential services. For example, low vaccination coverage has been ascribed to irregular vaccine supply in tandem with non-respect of cold chain principles, unpredictable budget flows and lack of coordination.Citation15 Socio-cultural features affecting immunization rates in Laos were found to be knowledge concerning vaccinations, distance to vaccination site, and vaccination status of peers.Citation15,16 The integration of a broader set of MCH services into outreach presented additional challenges in terms of composing a team with the required skills, financing and incentives, and coordination with communities. With this in mind, this study sought to assess factors associated with health providers that affect the delivery of outreach services and uptake of MCH services delivered through outreach.

Methods

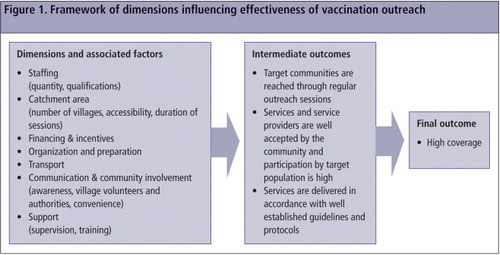

We used the dimensions and associated factors required to successfully deliver the intended set of interventions during outreach, as shown in , to guide the approach to the assessment and for development of the research instruments.

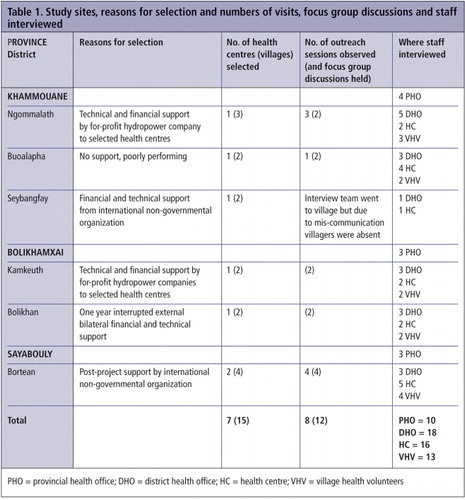

Study sites were purposively selected to capture a diverse picture of conditions and experiences with outreach services. A total of seven districts in three provinces were selected (Table 1), with field work implemented during the period September-October 2010. Within the three provinces, at total of seven health centres and 15 villages were visited as well as the respective district and provincial health offices. Outreach sessions were observed in a total of eight villages, and 58 semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted with ten representatives of Provincial Health Offices and 19 of the District Health Offices, 16 health centre staff members and 13 Village Health Volunteers. Interviewees at District and Provincial Health Offices included the MCH Coordinator and the EPI (Expanded Programme on Immunization) Coordinator. All interviewees were selected because they were directly involved with the outreach sessions, be it as general managers (Deputy Directors), experts (MCH and EPI Coordinators), support staff (Technical Staff), or implementers (Health Centre staff). In addition to the semi-structured interviews, 12 focus group discussions with 120 women with at least one child aged less than five years were conducted. These women were identified by the VHV of the respective villages.

Health staff at all levels were questioned concerning the kind of MCH services provided during vaccination outreach, catchment areas under responsibility and practices according to remoteness of villages, approaches to communication with target group people, budgeting and planning related to outreach, human resources implied, training, supervision, remuneration rules and practices, transportation, logistics and supplies, targeting, and issues and suggestions for improvement. Similar questions were asked to Village Health Volunteers. Questions during focus group discussions related to care-seeking behaviours, perception of the outreach sessions and associated services, use of the respective services, and familiarity with services at public health facilities.

Observation of outreach sessions by three interviewers started at the facility where availability of essential items such as vaccines and materials for antenatal care (ANC) was assessed together with the items taken for the outreach session. Health staff were accompanied on their trip to the village to elicit logistics involved and issues surrounding the journey, including duration of travel and transport used. During the outreach session at the village, notes were taken about tasks performed by each team member and villagers, interactions with mothers and villagers, number of people attending and duration of each outreach session.

All interviews and focus group discussions were recorded in Lao and transcribed in the same vernacular for analysis. Following the transcription process, an eight-day data analysis workshop was held, attended by all data collectors, whereby qualitative data were grouped and content analysed according to key themes at provincial, district, health centre and village level. When possible, information provided during interviews was triangulated with existing records and reports and/or direct observation during outreach.

Ethical clearance was provided by the Lao National Ethics Committee for Health Research (No. 322/NECHR). Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to interview.

The study was conducted towards the end of the rainy season, which meant that most health centres bar the ones visited were not accessible and therefore could not be included in the study. Additionally, since vaccination outreach tended to happen quarterly the study period did not necessarily coincide, especially since budget supply through government channels was erratic and unpredictable. As such, the data collection team was not able to observe outreach activities in Bolikhamxay Province. This was a qualitative study and the team only visited a small number of sites. Information collected relates specifically to the sites visited and individuals interviewed, and cannot necessarily be generalized.

Findings

Staffing for outreach sessions

The National Guidelines on Outreach ServicesCitation13 recommend two staff members per health centre to conduct outreach sessions at villages that can be visited within a day. For more remote villages requiring overnight stay, one staff member of the District Health Office (DHO) should accompany the two health centre staff. The health centres visited all had at least one female staff member, potentially facilitating delivery of gender-sensitive services such as antenatal examinations. The total number of staff members at those health centres ranged from two to six. The number of staff members in an outreach team was on average two, varying from one for villages near a health centre to ten (five expatriate non-governmental organization [NGO] staff members included). Generally, where external support existed from an NGO or other source (hydropower company),Footnote* outreach teams tended to be larger. Some key informants felt that two staff members were too few for an outreach team to adequately perform all required services: “To provide eight services there is a need for at least three staff; two is not enough to deal with the requirements” (District Health Staff, Bolikhamxai).

Outreach teams composed solely of health centre staff members (which usually meant only two individuals) tended not to divide responsibility for tasks when conducting outreach. When DHO staff members were involved, teams tended to be larger and include a wider variety of expertise with a larger number of services provided, with different team members allocated different tasks. In areas where DHOs or health centres were understaffed, there were examples of borrowing additional staff (from the hospital or military) to conduct outreach activities. Interviewees noted that borrowing staff resulted in lack of continuity, as each round of outreach was conducted by different individuals, losing the opportunity to develop rapport between health staff and community members.

Catchment area

The MoH differentiates between villages requiring overnight stay by outreach staff or not. Overnight stay villages are remote and challenging to reach and the outreach team should spend two nights in them. In non-overnight villages the outreach team is supposed to spend the whole day to deliver all services. Across the study sites, however, women in the focus group discussions reported that the average duration of outreach activities tended to be 2–3 hours. “Health workers usually come at 9am and finish by 11” (mother, Khamkeuth district). If the target population lists contained only a small number of women or children requiring services on a planned outreach day, staff would postpone the activity or send a message requesting these individuals to visit the health facility. Thus residents of small remote settlements tend to be discriminated against, contrary to the objectives of outreach sessions which are to extend services to remote communities. Where the duration of outreach activities was more than three hours, it was observed that this happened because health staff members were waiting either for villagers to return or for the village chief to be available for the feedback session. The number of villages covered by the visited health centres ranged from 3 to 9 with 3 to 17 vaccination sites. A village can have more than one vaccination site, and nearby villages can be clustered together under one name for administrative reasons.

Financing and incentives

In areas without external financial support, outreach activities only took place when government funding was received, and this could be very irregular. In such cases, the frequency depended on staff commitment. In one health centre, staff conducted outreach activities on a monthly basis using their own money, which was then reimbursed when funds arrived. Elsewhere, staff reported using revenues from the drug-revolving fund, which they used to cover the cost of transportation for outreach activities. Per diems for day trips were relatively similar across the sites (US$3.75–4.38) but there were considerable differences reported for overnight stays (US$5.00–8.75), depending on the type of financial support received.

Village Health Volunteers (VHVs) were involved in several ways to support outreach activities, including mobilizing villagers, growth monitoring, and/or providing health education. In some cases traditional birth attendants (TBAs) were also involved with weighing children and distributing iron folate tablets to pregnant women. In two districts, one VHV per village would receive US$1.25 as an incentive to assist with outreach sessions, while health centres supported by the hydropower company would pay US$1.90 to the VHV, TBA and Village Chief at each village. Health centres with only central government funding did not provide an incentive to anybody at village level. Although financial remuneration is justified in communities with subsistence economies, assistance by VHVs could be better optimized if their expected tasks were well defined and properly explained. It is unlikely that financial remuneration alone will result in improved service coverage, although it would minimize attrition and contribute to continuity and regularityCitation17. Positive relationships between health staff and village authorities appeared to be an important factor in mobilizing support from the community. This was also a finding by Phimmasane et al,Citation15 who recommended employing village chiefs for increasing attendance by target groups.

Organization and preparation

Preparation of equipment and materials appeared to be best in villages with well-functioning vital registration systems, so the exact number of pregnant women and children was known in advance. In areas without external support, staff members had to carry all relevant equipment with them each time they conducted outreach activities in a particular village. This included 2 stethoscopes, fetal stethoscope, blood pressure meter, weighing scale, thermometers, a curtain for ANC sessions, educational materials, and recording forms. Given that they usually travelled to outreach activities by motorbike, the logistical issues of transporting equipment were frequently raised by interviewees. Some respondents noted that equipment was sometimes left behind at the health centre when travelling to remote areas, and local substitutes used (for example, the health centre's growth monitoring equipment would be substituted by scales used for weighing rice). At some health centres, staff noted that they did not currently have all of the relevant equipment mentioned in the guidelines, while others complained of old equipment. Vital registration systems appeared limited and only health centres with external support employed lists containing all target group people and their uptake of the concerned health services.

Transport

Transport was financed at various rates, from US$1.25 – $5.00 per village, US$12.50 for 13 villages, one litre of petrol for 15km travel or 2 – 6 litres per village. If budgeted, one district would reimburse repairs to motorbikes while another provided US$2.50 per month for maintenance. No provision for maintenance and repairs was foreseen in the other districts. One motorbike had been provided per health centre in one district while in the others staff members had to use their own vehicle. Supplies, including vaccines, were to be collected from the DHO, often hours away, and vaccines had to be returned after outreach sessions, implying additional travel using the health centre's staff vehicle.

Scheduling of visits, communication and community involvement

It was found that outreach activities seemed to work best in areas where these followed a regular schedule, so that both health staff and communities could easily remember and plan around the dates. Irregular outreach sessions in tandem with poor communication of changes in timing are considered a major reason for low vaccination coverage in India.Citation17 Thus, adhering to the regular outreach schedule is important to ensure high attendance, especially if there are difficulties with communication, which is not uncommon in Laos. If the date of outreach sessions changed because of delays in availability of funds or supplies such as vaccines, health centre staff reported that they usually tried to inform villages in advance of their impending arrival. However, in some cases, interviewees noted that this was difficult due to the remoteness of the village or problems such as unavailability of telephone services. “We gave the information letter for the village health volunteer two days ago to the bus driver but the letter did not arrive. So when we got to the village in the morning nobody was waiting for us. This is the only village in our area without a phone signal.” (Health Centre staff, Khammouane).

Moreover, often advance warning was given only the day before the activity. Community members remarked that this did not give them sufficient time to return from their rice fields or other workplaces. Health centre staff reported that they conducted outreach activities in the early mornings although several village women noted that the teams still arrived after they have left for work or did not arrive until the afternoon. Many villagers expressed a preference for outreach activities to take place early in the morning. In the case of villages classified as overnight-stay, it was noted that in many areas health staff still tried to visit as a daytrip instead of arriving the night before.

Children proudly showing their stained finger following receipt of polio vaccination. This is to avoid them receiving the vaccine twice.

The study team observed that outreach teams tended to be poor communicators. They did not spend much time explaining to villagers what they would do, what the benefits of an intervention were, or what follow-up was required. During focus group discussions, participants confirmed this. “They [health worker] gave back the yellow card after injection [vaccination] and told that I could go back [home], they did not say anything else (mother, Khammouane). Better interactions with mothers as well as village committee members may result in better understanding of the benefits of preventive services and thus increase coverage rates.Citation15 The quality of the anthropometric assessment of children's nutrition status was observed to vary between sites, which was worrying since social demand for vaccination correlates with quality of services.Citation18

Acceptability of services and service providers

In spite of all the difficulties, village women reported being happy to wait for the outreach team as they valued the services and many women expressed a willingness to delay going to their fields to tend crops in order to wait for the outreach team to arrive, providing they had sufficient advance warning. Outreach services were appreciated because they were “good for babies” and because they reduced the need for pregnant women to travel out of the village for ANC services.

The National GuidelinesCitation13 stipulate that the final activity of any outreach session should be a feedback discussion between the outreach team and the village committee. In many of the study sites such meetings were reported to happen, though in some cases only because outreach teams required the village chief's signature for their reports.

Conclusions and recommendations

Our assessment found many laudable initiatives, and we observed successful attempts to implement the range of services recommended by the Ministry of Health guidelines. However, we found that the areas with the most effective outreach activities appeared to be those in which regular supportive supervision and monitoring were provided, either by DHO or Provincial Health Office staff, though most noticeably by staff of external projects or of the hydropower plant. Supervision tended to be conducted at quarterly intervals, subject to availability of funds, except for staff members of facilities supported by external agencies. Well-performing vaccination services appeared to be those benefiting from regular, intense supervision, in line with recommendations by Wallace, Dietz and Cairns,Citation6 who conducted a systematic review of the literature on integrating health services, including MCH care with immunization outreach.

The frequency of planned outreach activities varied from monthly to twice annually, although in practice outreach activities are often conducted less frequently than intended, especially in remote areas. Most interviewees thought that for outreach to be effective, it should be conducted monthly or bi-monthly. The actual frequency depended primarily on availability of budget funds. Another major factor was the accessibility of villages: many remote villages can be completely cut off during the rainy season, and difficult to access even in the dry season. In at least one case, the health staff interviewed admitted that there were a small number of villages in their catchment area that they had not visited at all, due to the difficulties of accessing them. The low frequency of outreach to remote villages may explain why vaccination coverage inversely correlates with remoteness from a health facility,Citation15 as observed elsewhere.Citation19 If agricultural and seasonal subsistence activities were not taken into account, the likelihood to reach women and children was also reduced, as the opportunity costs of losing income were too high to stay at home for outreach.

It was notable that both the frequency and quality of outreach activities were proportional to the amount of external support (both technical and financial) that was available to local health staff, including within a single district where only some villages or health centres received external support. A higher frequency of outreach should allow for increased coverage since there are more opportunities to reach people missed previously. The only districts that reported monthly outreach sessions all had major external financial and technical support. Additionally, villages benefiting from monthly services appeared relatively near to a health centre.

The extent to which vaccination and MCH outreach activities were integrated also varied enormously. In some areas, outreach activities remained limited to immunization, usually with supplementary distribution to children of vitamin A and de-worming tablets every six months. At the opposite end of the scale were those areas (again, usually those supported financially and technically by external projects) that provided a wide range of the MCH services and health education stipulated in the guidelines. Health staff in several areas even gave check-ups to the general population if anyone was sick. Even in those areas professing to conduct integrated outreach there were differences in the actual services provided, however. Immunization and the distribution of Vitamin A and de-worming tablets seemed to be the most widely provided.

Based on this study, we suggest the following to better enable integration of vaccination outreach with other MCH services.

At village level, to improve use and selection of Village Health Volunteers while providing better support and training for them; reduce the amount of bulky outreach equipment to be carried; enable advanced planning of regular and timely outreach, sufficient advance warning of changed dates, and better communication between health providers and communities; improve targeting of services through vital data registration and monitoring of uptake of MCH services; ensure staff compliance with set dates, adequate time spent in each village for activities and visits to each village, especially the most remote ones.

The DHO should define catchment areas of reasonable size and accessibility; conduct regular monitoring and supportive supervision; provide (refreshment) training for all health centre staff members; avoid overload of responsibilities on a small number of individuals and ensure that all villages are regularly visited.

The Ministry of Health should guarantee consistent, long-term political, financial and technical support and ensure timely and adequate supplies of consumables, while allocating more budget to enable higher frequency of outreach sessions. This may ensure results similar to those observed at facilities with external financial and technical support.

The current degree of financing by the government is unlikely to result in an increased coverage of children and pregnant women as envisaged, particularly while the most remote villages are hardly, if at all, visited by outreach teams.

Because vaccination coverage has remained low in LaosCitation20 and stagnated over recent years, the vaccination programme may be insufficiently robust to allow integration of other health services. The current low coverage of immunization is also inequitable, with the lowest levels among remote and poor communities,Citation21 which will most likely be exacerbated when more MCH services are added under the current conditions. In line with recommendations by Wallace et al,Citation6 it may be better to ensure high vaccination coverage through outreach before integrating other services. However, considering the inequitable access to MCH services by women in remote communities, together with the government's intention to extend such services to them, it may make more sense to increase the type and number of MCH services gradually during vaccination outreach, while simultaneously improving coverage of children and women receiving them. Consideration may be given to introducing the Reaching Every District (RED) strategy, that emphasizes vaccination outreach sessions, with inclusion of other services, that are planned and implemented with involvement of the target communities and with due consideration of the available local resources, including the government's financial commitment.Citation5

Acknowledgements

We thank the Burnet Institute survey team for conducting the qualitative research for this study, and Chantelle Boudreaux and Bob McLaughlin for their support with ordering the data. Sincere thanks to the provincial and district health authorities for their kind collaboration. This study was financed by Luxembourg Development and the World Bank. The opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of their affiliated organizations or the Lao Government.

Notes

* The hydropower company was required to ensure health service delivery as part of its concession agreements with the Lao Government to about 7,000 people displaced to 17 newly constructed villages over four districts by the construction of a dam. The company also had to ensure strengthening of the health facilities of the catchment areas in which the 17 new villages were located.

References

- KJ Kerber, JE de Graft-Johnson, ZA Bhutta. Continuum of care for maternal, newborn, and child health: from slogan to service delivery. Lancet. 370(9595): 2007; 1358–1369.

- G Jones, RW Steketee, RE Black, the Bellagio Child Survival Study Group. How many child deaths can we prevent this year?. Lancet. 362(9377): 2003; 65–71.

- IK Friberg, MV Kinney, JE Lawn. Sub-Saharan Africa's mothers, newborns, and children: how many lives could be saved with targeted health interventions?. PLoS Medicine. 7(6): 2010; e1000295.

- R Knippenberg, JE Lawn, GL Darmstadt. Systematic scaling up of neonatal care in countries. Lancet. 365(9464): 2005; 1087–1098.

- CJ Clements, D Nshimirimanda, A Gasasira. Using immunization delivery strategies to accelerate progress in Africa towards achieving the Millennium Development Goals. Vaccine. 26(16): 2008; 1926–1933.

- A Wallace, V Dietz, KL Cairns. Integration of immunization services with other health interventions in the developing world: what works and why? Systematic literature review. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 14(1): 2009; 11–19.

- AR Haws, AL Thomas, ZA Bhutta. Impact of packaged interventions on neonatal health: a review of the evidence. Health Policy and Planning. 22(4): 2007; 193–215.

- HA Elzein, ME Birmingham, ZA Karrar. Rehabilitation of the expanded programme on immunization in Sudan following poliomyelitis outbreak. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 76(4): 1998; 335–341.

- TV Ryder, V Dietz, KL Cairns. Too little but not too late: results of a literature review to improve routine immunization programs in developing countries. BMC Health Services Research. 8: 2008; 134. DOI: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-134.

- Ministry of Planning and Investment. Lao Reproductive Health Survey 2005. 2007; MoPI: Vientiane.

- Ministry of Planning and Investment Ministry of Health UNICEF. Lao PDR Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2006. 2008; MoPI: Vientiane.

- Ministry of Planning and Investment. Poverty in Lao PDR 2008. Lao Expenditure and Consumption Survey 1992/93–2007/08. 2010; MoPI: Vientiane.

- Ministry of Health. Guidelines: Outreach activities on Integrated Maternal, Newborn and Child Health Services. 2010; MoH: Vientiane.

- Ministry of Health. Strategy and Planning Framework for the Integrated Package of Maternal, Neonatal and Child Health Services 2009–2015: Taking Urgent and Concrete Action for Maternal, Neonatal and Child Mortality Reduction in Lao PDR. 2009; MoH: Vientiane.

- M Phimmasane, S Douangmala, P Koffi. Factors affecting compliance with measles vaccination in Lao PDR. Vaccine. 28(41): 2010; 6723–6729.

- M Maekawa, S Douangmala, K Sakisaka. Factors affecting routine immunization coverage among children aged 12–59 months in Lao PDR after regional polio eradication in Western Pacific Region. Bioscience Trends. 1(1): 2007; 43–51.

- AR Pater, MP Nowalk. Expanding immunization coverage in rural India; a review of the evidence for the role of community health workers. Vaccine. 28(3): 2010; 604–613.

- PH Streefland, AMR Chowdhury, P Ramos-Jimenez. Quality of vaccination services and social demand for vaccinations in Africa and Asia. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 77: 1999; 722–730.

- K Jamil, A Bhuiya, K Streatfield. The immunization programme in Bangladesh: impressive gains in coverage, but gaps remain. Health Policy and Planning. 14(1): 1999; 49–58.

- WHO/UNICEF. WHO/UNICEF Review of National Immunization Coverage 1980–2007: Lao People's Democratic Republic. At: http://www.who.int/immunization_monitoring/data/lao.pdf. Accessed 17 July 2011, undated.

- CG Victora, A Wagstaff, J Armstrong Schellenberg. Applying an equity lens to child health and mortality: more of the same is not enough. Lancet. 362(9379): 2003; 233–241.