Abstract

The unmet need for family planning in Uganda is among the world's highest. Injectable contraceptives, the most available method, were used by only 14.1% of married women in 2011. Recent data suggest that the main reason for unmet need is not lack of access, but fear of and unacceptability of side effects. In this qualitative study, 46 women and men were interviewed about their experience of injectable contraceptive side effects and the consequences for their lives. Thirty-two family planning service providers and policymakers were also interviewed on their perceptions. While using injectables, many of the women experienced menstrual irregularities and loss of libido. Both women and men experienced strained sexual relationships and expressed fear of infertility, often resulting in contraceptive discontinuation. Family planning service providers and policymakers often minimized side effects as compared to the risks of unintended pregnancy. Policymakers noted a lack of contraceptive alternatives and promoted family planning education to correct what they thought were misconceptions about side effects among both service providers and contraceptive users. Information alone, however, cannot diminish disturbances to social and sexual relationships. A common understanding of recognised side effects, not only with injectables but all contraceptives, is necessary if unmet need in Uganda is to be reduced.

Résumé

Les besoins insatisfaits de planification familiale en Ouganda sont parmi les plus élevés du monde. En 2011, les contraceptifs injectables, méthode la plus largement disponible, n'étaient utilisés que par 14,1% des femmes mariées. D'après des données récentes, la principale raison de l'insatisfaction des besoins ne serait pas le manque d'accès, mais la crainte et le refus des effets secondaires. Dans cette étude qualitative, 46 femmes et hommes ont été interrogés sur les effets secondaires des contraceptifs injectables et leurs conséquences sur leur vie. Trente-deux prestataires de services de planification familiale et décideurs ont aussi été questionnés sur leurs perceptions. En utilisant des contraceptifs injectables, beaucoup des femmes ont observé des troubles du cycle menstruel et une perte de libido. Les femmes comme les hommes ont ressenti des tensions dans les relations sexuelles et la crainte de la stérilité, aboutissant fréquemment à un arrêt des contraceptifs. Les prestataires de services et les décideurs minimisaient souvent les effets secondaires par rapport aux risques d'une grossesse non désirée. Les décideurs ont noté le manque de solutions de remplacement des contraceptifs et ont encouragé l'éducation à la planification familiale pour corriger ce qu'ils jugeaient comme des idées fausses sur les effets secondaires chez les prestataires de services et les utilisateurs. À elle seule, l'information ne peut cependant pas diminuer les troubles des relations sociales et sexuelles. Une compréhension commune des effets secondaires, non seulement des contraceptifs injectables, mais de tous les moyens de contraception, est nécessaire pour réduire les besoins insatisfaits en Ouganda.

Resumen

La necesidad insatisfecha de planificación familiar en Uganda figura entre las más altas del mundo. En 2011, solo un 14.1% de las mujeres casadas usaron anticonceptivos inyectables, el método más disponible. Datos recientes indican que la principal razón por la cual existe una necesidad insatisfecha no es falta de acceso, sino temor e inaceptabilidad de los efectos secundarios. En este estudio cualitativo, se entrevistaron a 46 mujeres y hombres respecto a su experiencia con los efectos secundarios de los anticonceptivos inyectables y sus consecuencias para su vida. Además, se entrevistaron a 32 prestadores de servicios de planificación familiar y formuladores de políticas respecto a sus percepciones. Mientras usaban inyectables, muchas de las mujeres presentaron irregularidades menstruales y pérdida de libido. Tanto las mujeres como los hombres experimentaron demasiada tensión en sus relaciones sexuales y temor de infertilidad, que a menudo llevaron al abandono del anticonceptivo. Los prestadores de servicios de planificación familiar y formuladores de políticas a menudo minimizaban los efectos secundarios en comparación con los riesgos del embarazo no intencional. Los formuladores de políticas indicaban escasez de opciones anticonceptivas y promovían la educación sobre la planificación familiar para corregir lo que creían ser ideas erróneas sobre los efectos secundarios entre prestadores y usuarias de servicios de anticoncepción. Sin embargo, la información por sí sola no puede disminuir las alteraciones en las relaciones sociales y sexuales. Para lograr la disminución de la necesidad insatisfecha en Uganda se necesita un entendimiento común de los efectos secundarios reconocidos, no solo de los inyectables sino de todos los anticonceptivos.

Contraceptive use has been conceptualized as a form of women's empowerment for giving women greater agency in their sexual and reproductive lives.Citation1,2 Especially in low-income countries with high maternal mortality, unsafe abortions, and few health care providers, access to contraception improves women's health by reducing unintended pregnancies.Citation2,3 In addition to enabling women and men to space their pregnancies, combined hormonal contraception has been associated with a decreased risk of iron-deficiency anaemia, ovarian and endometrial cancers. Progestin-only formulations similarly reduce the risk of anaemia and endometrial cancer and are safe during breastfeeding.Citation2,4

Alongside these benefits, progestin-only hormonal contraceptives have known side effects. The most common side effects of injectables include initially prolonged and irregular menses, experienced by 90% of users of DMPA (brand name Depo Provera). After 12 months of use, infrequent menses are common, and 25–40% of women develop amenorrhoea (no menstruation). Additionally, injectables can cause weight gain, dizziness, abdominal bloating, decreased libido and loss of bone mineral density (reversible). Finally, return to fertility is, on average, delayed by 7–9 months after discontinuation.Citation2,4

In low-income countries, injectables have several advantages: they require minimal provider training and do not require patient follow-up beyond the woman returning regularly for repeat injections.Citation5,6 Furthermore, injections can be more easily concealed from partners than pills and other methods. Lastly, injectables are effective: less than 1% of women become pregnant within a year with consistent use; 3% with inconsistent use.Citation2 Consequently, injectables are promoted in many low-income countries.Citation7

Contraceptive use in Uganda

Uganda has among the world's highest unmet need for family planning among married women of reproductive age (34%), and one of the highest total fertility rates (6.2). Unmet need is far higher among rural women (37%) than urban women (23%).Citation8 In this context, approximately 40% of pregnancies are unintended, and nearly 40% of these result in unsafe abortions, constituting 20% of maternal deaths.Citation9,10

According to the 2011 Uganda Demographic & Health Survey (UDHS), injectables are the most commonly used method (14.1%), followed by traditional methods (4.0%), the pill (2.9%), female sterilization (2.9%), male condoms (2.7%) and implants (2.7%).Citation8 Contraceptive use is not only determined by demand, but also by availability, accessibility and acceptability of methods. Thus, some women using injectables may actually prefer a less available method.

Limited contraceptive availability, the extent of which varies by region, method and type of facility, is cited as one reason for unmet need.Citation11,12 According to a 2007 health service assessment among a sample of urban and rural public and private facilities, including hospitals, health centres and HIV clinics, progestin-only injectables, combined oral contraceptive pills and male condoms were available in approximately 80% of facilities while long-term and permanent methods were available in fewer than 5% of facilities.Citation13 Contraceptive stockouts, attributed to funding shortages, regulatory issues and forecasting difficulties, also impede availability, although stockouts of injectables have decreased since 2009 with integration of these commodities into the national pull-based distribution system and distribution tracking.Citation14,15 Still, even when methods are available, long distances to facilities, lack of transportation and time-consuming household activities limit women's access.

According to 2006 UDHS data, however, only 1% of currently married women with unmet need for contraception in Uganda identified lack of availability as their main reason for not using contraceptives.Citation16 In fact, fear of side effects was the most commonly reported reason (29%), followed by health concerns (13%).Citation17 Similarly, in the 2011 UDHS, 22% of women had discontinued pills and 23% injectables in the first 12 months of use due to fear of side effects and health concerns.Citation8

Yet few peer-reviewed studies have explored the impact of these side effects on people's lives. The most recent study in Uganda, to our knowledge, was published in 1994.Citation18 Without in-depth qualitative data, both the Ugandan and international family planning literature often posit that fear of contraceptives is fuelled by myths and misconceptions.Citation19–22

This qualitative study aimed to explore: the acceptability of injectable hormonal contraception (“injectables”, mainly DMPA); the side effects experienced by women and the impact on their relationships; the ways in which service providers and policymakers understood and addressed users' experiences of side effects; and the health and policy implications of unmet need and contraceptive use at a population level of these perspectives. Data on other methods were also collected but are not reported here.

Methods and participants

This study aimed to contextualize perceptions of injectables based on a theoretical approach used in Amy Kaler's investigation of rumours in African communities that public health interventions, such as vaccination campaigns, caused sterility.Citation23 Kaler focuses on rumour production, without judging rumours to be true or false. This provides a framework for understanding rumours as products of collective knowledge, influenced by local conditions.Citation23

By not judging fears or experienced side effects as true or ill-founded, this study sought to understand the physiological and social experiences of using injectables, their implications for daily life in the current cultural and social context, and the generation of community-based knowledge about side effects arising from these experiences.

A research permit with ethical clearance was obtained in September 2009 from the Uganda National Council of Science and Technology. Qualitative data were collected from November 2009 to January 2010.

Data from the general population, service providers and two policymakers were collected in rural and urban sites in Mbarara, a southwestern district. Additional data from policymakers was collected in Kampala. Mbarara district was chosen because prior work done there by the authors generated connections with health system authorities. District health officials, health centre administrators, Reproductive Health Uganda and Marie Stopes Uganda identified specific research sites with the authors.

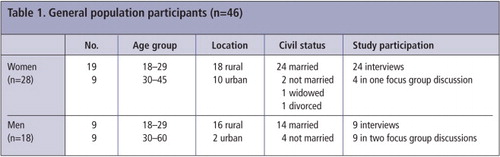

Three groups of informants were included to capture a range of perspectives. The first included 46 women and men (aged 18–60 years) from the general population; the second, family planning service providers; and the third, male and female policymakers regarded by the authors as influential in Ugandan family planning policy.

Rural participants from the general population were emphasized in recruitment because of their higher unmet need. Participants were recruited while waiting for health services (n=8) or attending NGO activities (n=11) or were identified by Reproductive Health Uganda peer educators (n=6). Others (n=25) were recruited randomly in their villages. Informed consent was obtained from each participant.

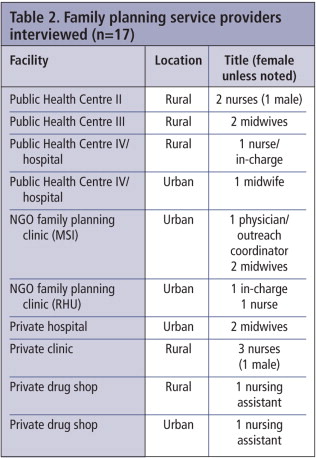

Service providers (n=17) working across public and private sectors were enrolled, as 52% of people received family planning from non-governmental providers, including private clinics, hospitals and pharmacies and/or NGOs at that time.Citation16

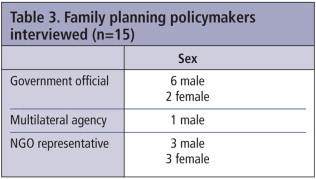

Policymakers (n=15) were selected by analysing reports and organizations, to gauge their influence on Ugandan family planning policy, and those who were interviewed were asked to identify others (snowball technique).

One co-author (WT) with skills in group facilitation and trust-building, language capabilities and ability to speak candidly with male participants, conducted interviews and focus group discussions in Runyankole with the general population. Focus groups were added to facilitate dialogue and create comfort with the topic of discussion. Two co-authors (MT & MH) conducted interviews in English with service providers and policymakers.

All recorded and transcribed interviews were reviewed for correct translation and/or transcription by someone other than the interviewer. Eighteen interviews were not recorded as a result of technical problems or interviewee preference but were immediately documented in field notes. Text Analysis Markup System (TAMS) Analyzer software was used to analyse transcripts and notes.Citation24

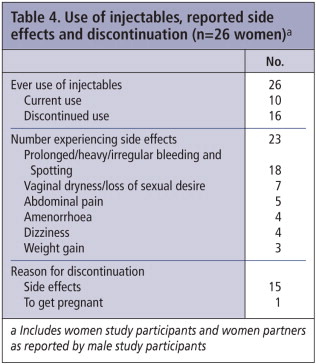

Contraceptive users and their partners

All women and men interviewed (n=46) described family planning as desirable, noting its positive aspects such as: more manageable and affordable family size; health benefits of spacing; and ease of use. No major differences were noted between the women's and men's responses. Twenty-six of the 46 participants reported current (n=10) or prior (n=16) injectable use by themselves or their women partners, of whom 23 (88.5%) experienced side effects (Table 4). Of the 20 participants who had no personal experience of injectables, 13 had heard about side effects experienced by others, while seven did not mention side effects.

Side effects most commonly included menstrual irregularities, with prolonged/excessive menses and/or spotting reported by 18, and amenorrhoea by four others. Other effects included: vaginal dryness and/or loss of libido (n=7), abdominal pain (n=5), dizziness (n=4) and weight gain (n=3). A male participant described the community's perception of side effects this way:

“The injection has a lot of problems. There is bleeding, getting dry, you find a woman does not have appetite for a man any more.” (Sam)

Menstrual irregularities

All 23 women who personally experienced side effects (reported by themselves or their male partners), as well as the 13 participants with no personal experience of injectables, said that menstrual irregularities disturbed women's well-being and social relations.

“… Menstruation sometimes [makes] you hate yourself, mostly when it is too [heavy] or [lasts] a long time. You don't feel good about yourself, you are washing all the time.” (Edith)

Eighteen participants were concerned about excessive blood loss, including two who were worried about women bleeding to death. Two people connected excessive bleeding to women's decreased ability to work and economic consequences.

“[Bleeding] becomes a problem because [we] are always working hard. If she bleeds a lot, gets stomach aches and starts getting dizzy, that means that she will stop working… if she does not harvest my millet, what will she eat tomorrow?” (Wilson)

Sexual and domestic conflict

Injectable-associated menstrual irregularities limited women's sexual availability. Vaginal dryness and loss of libido, mentioned by seven participants as lessening sexual desire, pleasure and availability, was problematic because wetness during intercourse is desirable in southwestern Uganda:

“I was doing great whenever I would have sex with my husband, but when I started the injection, my life was cut short … when you become dry you don't feel like you want a man.” (Jacqueline)

“When problems started coming up because of family planning, he turned against me… when you cannot satisfy a man in bed that's when sometimes he drinks a lot and he chases you out of the house.” (Immaculate)

“My man was about to leave me because of [dryness] and then I decided to stop [using the injectable]... my man likes me now and has never complained about me being dry anymore.” (Irene)

“I just stopped and gave birth. But even now I ask myself what I should do. I don't want to have another child… A man can chase you away from the house just because of [dryness].” (Angela)

Fear of infertility

Eight participants worried that injectables caused infertility. As with reduced sexual pleasure and availability, fear of infertility and delayed return to fertility were not only problematic in themselves but also raised concerns about relationship stability.

“My friend used it and she later failed to conceive again for one year. She just gave birth last month but her husband was about to leave her for another woman, blaming her for using family planning.” (Sylvia)

Discontinuation

All participants who had discontinued injectable use (n=16) cited side effects as the main reason, except one woman who had wanted to conceive. Eight mentioned that menstrual irregularities and their impact on intimate relationships made them discontinue use.

When participants reported side effects to service providers, three were told to wait for initial effects to subside and five were advised to switch to a different method. Some expressed frustration with that advice:

“[Service providers] say we should be strong and wait. So you can't find anything to do about it.” (Immaculate)

Contraceptive service providers

Fifteen female and two male providers were interviewed. All quotes below are from female providers, as women more frequently provided services in the facility sites. Six service providers expressed concern about health-related side effects of injectables, namely heavy and prolonged bleeding, vaginal dryness and their social implications.

“[T]he man can decide to divorce you for another woman… We wouldn't want to see family planning causing such things.” (NGO clinic in-charge)

“[E]ven if the side effects occur, they can be handled. Unless really it fails to be handled on drugs then maybe it's better to have [side effects] than having unwanted pregnancies.” (NGO physician)

“Someone spends like two years without going into her menstruation. For that we normally discourage young mothers… someone with one child, to use Depo. We don't provide it.” (Public facility midwife)

“I tell them that if you see the bleeding… just continue and don't bother to come back here… That it can happen but it will not last for a long time.” (Public nurse)

“[The district] advises that you inject again but the mother may not even want that injection any more… So I prefer [giving combined contraceptive pills].” (Public clinic in-charge)

Policymakers

Ten male and five female policymakers were interviewed. Many policymakers (n=9) believed that widespread myths and misconceptions deterred people from using contraception, especially fear of infertility. Although all 15 policymakers interviewed noted that some side effects were real, the weight given to these side effects varied. There were no major differences between male and female policymakers.

Nine policymakers emphasized that all medicines have side effects, but thought side effects described by contraceptive users were exaggerations, distorted by rumours:

“If you use Depo Provera, you bleed, and you will have that excess bleeding on and off. That is true, but when you listen to what people say, they exaggerate. It becomes more of a misconception.” (Female government official)

“The fear of side effects is just the imagination of the people, which of course can be cured through massive education and provision of facts to the population.” (Male politician)

All policymakers suspected service providers had insufficient contraceptive knowledge, especially those in private pharmacies. Policymakers also acknowledged limited availability, accessibility and affordability of methods, due to stockouts, long distances to the nearest (public) providers, and insufficient provider skills, commodities and equipment for providing long-term and permanent methods as the main limitations to delivering family planning services. They were concerned with the lack of contraceptive alternatives:

“If we have the pills, the condoms and the injectables, then people don't have a wide method mix. If side effects occur, then we are not going to… have another option to give them.” (Female government official)

“[W]e have been giving [communities] messages, but we never listen to what they are saying ...[Policymakers] don't appreciate the magnitude of side effects for the woman. It has been mainly men, with male biases, making these policies... They are not in a hurry to make more favourable policies because they do not appreciate the problem and how serious it is to an individual.” (Female NGO employee)

Discussion

In sum, all women and men interviewed valued family planning, but side effects of injectables were prevalent and negatively affected women's health, working capacity, sexual pleasure and relationship stability. Social implications of contraceptive side effects have also been documented elsewhere. Two studies from Kenya, for example, linked contraceptive-associated loss of libido and excessive bleeding to sexual and domestic disturbances.Citation25,26

All the service providers and policymakers in this study also valued family planning and acknowledged its benefits. While some service providers and policymakers recognized the social impacts of commonly reported side effects, they considered them to be exaggerated, manageable and/or minor compared with the risks of unintended pregnancy. More than half of women (including female partners of male participants) had used injectables. Side effects were prevalent and sufficiently significant that some women discontinued use and got pregnant despite their desire not to do so – precisely what they and service providers hoped to prevent. Failure to acknowledge the full impact of side effects may therefore contribute to poor outcomes and mistrust of the health system.

Policymakers recognized the need for a range of accessible methods, but family planning programmes are insufficiently funded. When information is the only solution available, deficient knowledge is blamed, and negative reactions by women or men to existing contraceptives are treated as misconceptions. Conceptualizing side effects as misconceptions, however, precludes accurate problem definition and, consequently, problem-solving. Further, a policy response consisting only of education places the main fault and responsibility on service providers and contraceptive users themselves, de-emphasizing the limited effectiveness of the health system and the government's own role in creating responsive, system-wide policy solutions.

The authors do not suggest that contraceptive information should not be provided, or that it will not increase contraceptive use. On the contrary, information is crucial, particularly when experienced side effects (e.g. delayed fertility) are misunderstood (e.g. thought to be permanent). Still, information alone may not increase use among women and men who experience unacceptable side effects.

Finally, it is concerning that respondents in each group implicitly described power differentials within relationships, male opinions of side effects that contributed to injectable discontinuation and the potential for gender-based violence. Previous research in Uganda has linked non-use of contraception and unintended pregnancies to gender inequality and male opposition to contraception,Citation27,28 also suggested by this study. Importantly, none of the men interviewed for this study were opposed to contraception per se, but only to side effects that worried them or affected them adversely, particularly fear of infertility and women's reduced desirability or availability for sex.

Recommendations for family planning policy

Trivialization of reported side effects by service providers and policymakers can contribute to contraceptive discontinuation and unintended pregnancies while precluding effective responses. Family planning policymakers and providers must therefore accept, acknowledge and address the physical, social and economic side effects of contraception experienced by users.

Although enhanced provider education and patient counselling will probably not dramatically increase contraceptive use alone, both are crucial. Service providers require capacity-building in recognizing and treating side effects (with acceptable options); clearly communicating correct information to patients; and successfully transitioning patients to other methods when side effects limit use, acknowledging that some side effects cannot be ameliorated.Citation29,30 Training curricula should be adjusted accordingly.

Patients requested and deserve accurate information on the proven side effects of contraceptive methods and their frequency and duration, measures to mitigate those side effects, and ways in which to avoid unintended pregnancy while changing or discontinuing methods. Counselling should be provided to women and their male partners, either individually or as couples, recognizing that gender inequality affects contraceptive decision-making. Mobile phones could be used to connect rural populations with decentralized community health workers knowledgeable in family planning.

Finally, a range of high quality, acceptable contraceptive methods – as well as products to palliate their side effects – should be made widely available and accessible. When appraising alternative methods for distribution and/or scale-up, effectiveness and side effects should be carefully balanced against acceptability.Citation31 For example, efforts are ongoing to make intra-uterine devices (IUDs), implants and male/female sterilization more available, but their acceptability needs to be collectively weighed during health planning and at the point of care with patients.

Alternatively, cervical barriers are discrete, do not affect menstruation or vaginal lubrication and can be used in resource-limited settings.Citation32–35 Methods for men should also be made available. Condoms and female condoms do not affect menstruation either, but are short-term methods with currently low use rates in spite of the high prevalence of HIV in Uganda, suggesting limited accessibility or acceptability (and perhaps also insufficient promotion). Because combined hormonal injectables provide similar long-term contraception with fewer menstrual changes and quicker return to fertility, they may be a good option for populations accustomed to regular but infrequent injections.Citation2,4,36

Lubricants and lubricated condoms can help to mitigate vaginal dryness. To limit the consequences of menstrual irregularities, menstrual cups/management methods or cervical barriers could enable sex during menses by preventing penile contact with menstrual blood (one cervical barrier under development in Zimbabwe might double as a menstrual cupCitation37). These products should be made more available and accessible, and providers should be trained in providing them.

By interrupting sexual activity and jeopardizing fidelity, contraceptives can conflict with the purpose of family planning – to enjoy a safe sexual life with one's partner(s) while preventing or spacing pregnancies. Advocacy efforts should target the Health Ministry, NGOs and multilateral donors to move beyond blaming myths and misconceptions for low contraceptive use.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to all interviewees; to our supervisors Klaus Lindgaard Høyer and Lisa Ann Richey; and to Siri Tellier and Ernst Lauridsen for their comments. Our co-author, Willington Taremwa, sadly passed away while this article was being written. The study was funded by: Oticon Fonden, DANIDA Fellowship Centre and the Danish Family Planning Association. Funders had no involvement in study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of data, writing or submission of the paper.

References

- J Wajcman. Delivered into men's hands? The social construction of reproductive technology. G Sen, R Snow. Power and decision – the social control of reproduction. 1994; Harvard University Press: Boston.

- World Health Organization. Family Planning: Fact Sheet No.351. 2012; WHO: Geneva.

- World Health Organization. The prevention and management of unsafe abortion. Report of a technical working group. 1992; WHO: Geneva.

- World Health Organization Department of Reproductive Health and Research and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health/Center for Communication Programs (CCP) Knowledge for Health Project. Family Planning: A Global Handbook for Providers (2011 update). 2011; CCP and WHO: Baltimore and Geneva.

- S Malarcher, O Meirik, E Lebetkin. Provision of DMPA by community health workers: what the evidence shows. Contraception. 83(6): 2011; 495–503.

- J Stanback, AK Mbonye, M Bekiita. Contraceptive injections by community health workers in Uganda: a nonrandomized community trial. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 85(10): 2007; 768–773.

- J Stanback, J Spieler, I Shah. Community-based health workers can safely and effectively administer injectable contraceptives: conclusions from a technical consultation. Contraception. 81(3): 2010; 181–184.

- Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) and ICF International Inc. Uganda Demographic & Health Survey 2011. 2012; UBOS and Calverton MD: ICF International: Kampala.

- World Health Organization. Unsafe Abortion: Global and Regional Estimates of the Incidence of Unsafe Abortion and Associated Mortality in 2008, 6th ed. 2011; WHO: Geneva.

- S Singh, E Prada, F Mirembe. The incidence of induced abortion in Uganda. International Family Planning Perspectives. 31(4): 2005; 183–191.

- Uganda Ministry of Health. Uganda Reproductive Health Commodity Security Strategic Plan 2009/10–2013/14. 2009; MoH: Kampala.

- Uganda Ministry of Health. Road Map for Accelerating the Reduction of Maternal and Neonatal Mortality and Morbidity in Uganda 2006–2015. 2008; MoH: Kampala.

- Uganda Bureau of Statistics and Macro International Inc. Uganda Service Provision Assessment Survey 2007. 2008; MoH: Kampala.

- Chattoe-Brown A, Bitunda A. Reproductive Health Commodity Security – Uganda country case study: Commissioned jointly by the Department for International Development and the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2006.

- Uganda Ministry of Health. Annual Health Sector Performance Report 2010–11. 2011; Uganda MoH: Kampala.

- Uganda Bureau of Statistics and Macro International Inc. Uganda Demographic & Health Survey 2006. 2007; UBOS and Kampala: Macro International Inc: Calvertaon MD.

- S Khan, SEK Bradley, J Fishel. Unmet need and the demand for family planning in Uganda – further analysis of the Uganda Demographic & Health Surveys, 1995–2006. 2008; Macro International Inc: Calverton MD.

- L Nakato. Have you heard the rumour?. African Women & Health: a Safe Motherhood Magazine. 2(3): 1994; 23–27.

- M Campbell, NN Sahin-Hodoglugil, M Potts. Barriers to fertility regulation: a review of the literature. Studies in Family Planning. 37(2): 2006; 87–98.

- A Flaherty, W Kipp, I Mehangye. ‘We want someone with a face of welcome’: Ugandan adolescents articulate their family planning needs and priorities. Tropical Doctor. 35(1): 2005; 4–7.

- LM Williamson, A Parkes, D Wight. Limits to modern contraceptive use among young women in developing countries: a systematic review of qualitative research. Reproductive Health. 6: 2009; 3.

- Uganda Ministry of Health. Revised Reproductive Health Communication Strategy. 2009; Uganda MoH: Kampala.

- A Kaler. Health interventions and the persistence of rumour: the circulation of sterility stories in African public health campaigns. Social Science & Medicine. 68(9): 2009; 1711–1719.

- UH Graneheim, B Lundman. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today. 24(2): 2004; 105–112.

- N Rutenberg, SC Watkins. The buzz outside the clinics: conversations and contraception in Nyanza Province, Kenya. Studies in Family Planning. 28(4): 1997; 290–307.

- A Kaler, SC Watkins. Disobedient distributors: street-level bureaucrats and would-be patrons in community-based family planning programs in rural Kenya. Studies in Family Planning. 32(3): 2001; 254–269.

- DK Kaye, M Mirembe, G Bantebya. Domestic violence as risk factor for unwanted pregnancy and induced abortion in Mulago Hospital, Kampala, Uganda. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 11(1): 2006; 90–101.

- DK Kaye. Community perceptions and experiences of domestic violence and induced abortion in Wakiso district, Uganda. Qualitative Health Research. 16(8): 2006; 1120–1128.

- World Health Organization. Contraception discontinuation and switching in developing countries, Research Policy Brief. 2012; WHO: Geneva.

- H Bhargava, JC Bhatia, L Ramachandran. Field trial of Billings ovulation method of natural family planning. Contraception. 53(2): 1996; 69–74.

- JE Darroch, G Sedgh, H Ball. Contraceptive Technologies: Responding to Women's Needs. 2011; Guttmacher Institute: New York.

- T Ravindran, S Rao. Is the diaphragm a suitable method of contraception for low-income women: a users' perspectives study, Madras, India. Beyond Acceptability: Users' Perceptions on Contraception. 1997; Reproductive Health Matters: London, 78–88.

- A Bulut, N Ortayli, K Ringheim. Assessing the acceptability, service delivery requirements, and use-effectiveness of the diaphragm in Colombia, Philippines, and Turkey. Contraception. 63(5): 2001; 267–275.

- A van der Straten, N Sahin-Hodoglugil, K Clouse. Feasibility and potential acceptability of three cervical barriers among vulnerable young women in Zimbabwe. Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care. 36(1): 2010; 13–19.

- PS Coffey, M Kilbourne-Brook. Wear and care of the SILCS diaphragm: experience from three countries. Sexual Health. 7(2): 2010; 159–164.

- AM Kaunitz. Lunelle monthly injectable contraceptive. An effective, safe, and convenient new birth control option. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 265(3): 2001; 119–123.

- S Averbach, N Sahin-Hodoglugil, P Musara. Duet for menstrual protection: a feasibility study in Zimbabwe. Contraception. 79(6): 2009; 463–468.