Abstract

In Central America, approximately 12% of women report ever having been forced to have sex by an intimate male partner, and sexual violence by others is also a frequent experience. All Central American countries are signatories to human rights agreements that oblige States to ensure access to comprehensive health services for victims of sexual violence, but there is limited information as to whether these agreements have been translated into policy and practice. This article critically examines health sector guidelines for the treatment of sexual violence in El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua, and reports on an assessment of services in 34 private- and public-sector facilities in the four countries. Overall, policies were consistent with international agreements and included guidance on detection and documentation of violence, forensic examination, treatment, referral and follow-up care. However, only a small proportion of women who experience sexual violence actually seek care. The challenge facing all four countries is to turn policy into practice. Screening practices were inconsistent, and policies needed to indicate more clearly the roles and responsibilities of health care providers and forensic specialists. Finally, women's right to privacy and confidentiality in reports of cases to legal authorities needed further consideration, as well as the importance of providing all services at a single location.

Résumé

En Amérique centrale, près de 12% des femmes déclarent qu'un partenaire intime les a forcées à avoir des relations sexuelles et les violences sexuelles perpétrées par d'autres sont aussi fréquentes. Tous les pays centraméricains sont signataires d'accords relatifs aux droits de l'homme qui les obligent à garantir l'accès des victimes des violences sexuelles à des services de santé complets, mais on manque d'informations pour déterminer si ces accords sont traduits dans la politique et la pratique. L'article examine de manière critique les directives du secteur de la santé pour le traitement des violences sexuelles en El Salvador, au Guatemala, au Honduras et au Nicaragua, et rend compte d'une évaluation des services dans 34 centres privés et publics des quatre pays. En général, les politiques respectaient les accords internationaux et incluaient des conseils sur la détection et la documentation des violences, l'examen médico-légal, le traitement, le transfert vers d'autres professionnels et le suivi. Néanmoins, seule une petite proportion des victimes de violences sexuelles demandent des soins. Dans les quatre pays, la difficulté est de mettre la politique en pratique. Les méthodes de dépistage sont imprévisibles et les politiques n'indiquent pas assez clairement les rôles et les responsabilités du prestataire de santé et de l'expert médico-légal. Enfin, le droit des femmes à la confidentialité et au respect de leur vie privée dans les rapports sur les affaires adressés aux autorités judiciaires mérite une attention plus soutenue, comme l'importance de fournir tous les services dans un même lieu.

Resumen

En Centroamérica, un 12% de las mujeres relatan haber sido obligadas alguna vez por una pareja íntima de sexo masculino a tener relaciones sexuales; la violencia sexual perpetrada por otras personas también es una experiencia frecuente. Todos los países centroamericanos son signatarios de los acuerdos de derechos humanos, que obligan a los Estados a garantizar acceso a los servicios integrales de salud para las víctimas de violencia sexual, pero existe limitada información en cuanto a si estos acuerdos se han traducido en políticas y prácticas. En este artículo se examinan críticamente los lineamientos del sector salud para el tratamiento de la violencia sexual en El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras y Nicaragua; además, se informa sobre un diagnóstico de los servicios en 34 unidades de los sectores público y privado, en los cuatro países. En general, las políticas concordaron con los acuerdos internacionales e incluían orientación sobre la detección y documentación de actos de violencia, examen forense, tratamiento, referencia y cuidados de seguimiento. Sin embargo, solo una pequeña proporción de las mujeres que sufren violencia sexual buscan atención. El reto que enfrentan los cuatro países es convertir las políticas en práctica. Las prácticas de tamizaje no eran sistemáticas. Las políticas deben indicar con más claridad las funciones y responsabilidades de los profesionales de la salud y especialistas forenses. Por último, el derecho de las mujeres a la privacidad y confidencialidad en casos denunciados a las autoridades, así como la importancia de ofrecer todos los servicios en un solo lugar, merecen más consideración.

Sexual violence against women is prevalent throughout the world,Citation1 including in Central America.Citation2–6 Sexual violence is a human rights violationCitation7,8 with devastating consequences, including physical injury, unwanted pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), HIV, depression and other psychological problems.Citation1 It may also hinder victims' ability to participate in employment and educational opportunities. Sexual violence encompasses both penetrative (forced sex or rape) and non-penetrative acts of sexual abuse; it is perpetrated by intimate partners as well as non-partners.Citation9 Footnote* National estimates from Guatemala (2008),Citation2 Nicaragua (2006),Citation3 and El Salvador (2008)Citation4 suggest that around 12% of women aged 15–49 years have been forced to have sex by an intimate male partner and that women are frequently victims of sexual violence perpetrated by non-partners.Citation2–6 Macro-level risk factors for sexual violence in Central America include high rates of crime and weak social controls, which contribute to an atmosphere of high tolerance for violent behaviour.Citation10 In addition, about half of the region's population live in poverty,Citation11 which may exacerbate women's vulnerability by limiting their ability to leave violent relationships, making them more vulnerable to sexual coercion in exchange for material goods, and/or increasing their exposure to high-risk situations.Citation1,12 Other risk factors include norms that legitimize violence against women and keep child sexual abuse hidden.Citation6 Although criminal laws in the region penalize sexual assault and other forms of sexual aggression,Citation13–16 the Interamerican Court on Human Rights in 2011 documented a “pattern of judicial ineffectiveness vis-à-vis acts of sexual violence [in Central America]…[that] promotes and perpetuates impunity in the vast majority of cases...”Citation17

All Central American countries are signatories to international agreements that define sexual violence as a human rights violation and oblige State parties to take measures to eradicate sexual violence and ensure access of victims to justice- and health-related services.Citation7,8 Countries in the region and throughout Latin America have passed legislation on violence against women that reflect these mandates.Citation6 However, limited information is available as to whether these laws are being translated into policy and practice in Central American health care facilities that provide services to victims of sexual violence.

The study

The current study is a component of a larger project coordinated by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) in partnership with several agencies and institutions in El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua.Citation18 The goal of the project is to contribute to a “coordinated response model”Citation19 that recognizes that inter-sectoral collaboration is required to ensure victims' access to comprehensive services. The aims of the current study, as part of that project, were to: (1) describe health sector guidelines for the delivery of care to victims of sexual violence in the four countries and (2) document the availability of services for victims in selected health care facilities (hospitals and health centres) in relation to a model of comprehensive health care developed by UNFPA and Ipas.Citation20 The UNFPA/Ipas model incorporates recommendations of the World Health Organization (WHO)Citation21 and the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO)Citation22 and defines comprehensive care as victim-centred care that includes detection and documentation of violence and its health sequelae; forensic examination; medical treatment, including prophylactic services; referral to legal and mental and other health services, and follow-up care. The model is based on a review of best practices from the literature and the experiences of several organizations working in Latin America in 2005–2006 including PAHO; International Planned Parenthood Foundation (IPPF); Ipas in Bolivia, Brazil, Mexico and Nicaragua; Comissão de Cidadania e Reprodução in Brazil; Catolicas por el Derecho a Decidir and Grupo de Información en Reproducción Elegida (GIRE) in Mexico.Citation18

Methods

Ministry of Health websites and contacts with authorities in government institutions were used to identify relevant policies. For each guideline, we summarized content related to violence detection and documentation; forensic examination; and medical treatment, referral and follow-up.

UNFPA representatives in each country determined which facilities were to be included in the study, using a convenience sample. Forty hospitals and health centres were selected which were providing services to victims of sexual violence. Facilities were prioritized for inclusion if they were located in areas where the risk for sexual violence was elevated, based on locally available data.

Administrators of selected facilities were provided with a study description and copies of the data collection instruments, and were informed that no identifying data would be collected from staff or medical records. All of the facility administrators consented to participate. They notified staff who provided services to victims of sexual violence that they would be asked to meet with the researcher on a site visit to answer questions and facilitate access to records. During the data collection period (August 2008 through January 2009), six facilities were excluded because they did not provide on-site medical care to victims of sexual violence, leaving 34 facilities.

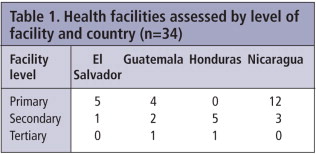

Most facilities were at primary level (n=21) or secondary level (n=11); 22 were in the public sector. Most of the rest were local non-governmental organizations (NGOs) with extensive experience providing services to victims of sexual violence (Table 1). All the NGO/private facilities provided services at no cost and offered violence-related care and other health care services. Two of the facilities were located in rural areas (both in Guatemala), seven were in the four capital cities, and the remainder in other urban areas.

A questionnaire developed by Troncoso et alCitation23 was used to interview and obtain data from facility staff and medical records on sexual violence detection and documentation, forensic examination, treatment and referral services offered to victims, including medications and diagnostic tests, and staffing and facility infrastructure. Participating staff were asked to randomly select the medical records of patients seen during the previous six months, which were examined to see what information was being documented. Most of the facilities were able to produce four such files, as requested.

Findings

Health sector guidelines for the care of victims of sexual violence were issued by the Ministries of Health in El Salvador in 2007,Citation23 Guatemala in 2006,Citation24 and Nicaragua in 2006.Citation25 The El Salvador and Nicaragua guidelines also addressed family violence. Guatemala also published a guideline for the treatment of family violence in 2008,Citation26 which included care for sexual violence perpetrated by partners or family members. Honduras did not have specific health sector policies on care for sexual violence except for 1997 guidelines on health services for adolescents which included services that should be provided for adolescent victims of sexual violence.Citation27

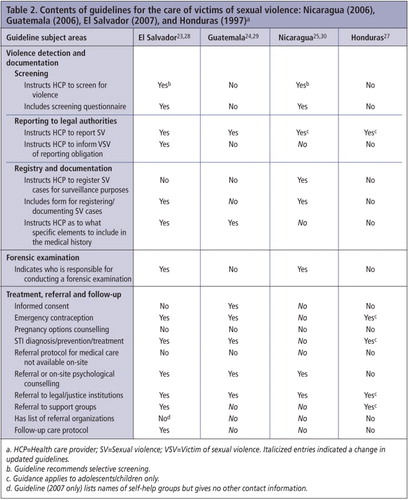

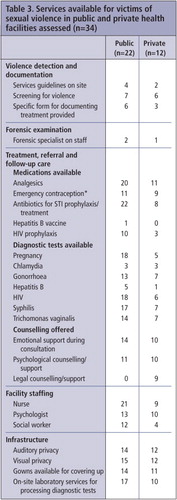

The content of the four sexual violence guidelines is summarized in Table 2. Facilities assessment findings are summarized in Table 3. Three of the four guidelines, excluding Honduras, made specific mention of human rights agreements that oblige States to address sexual violenceCitation23,25,26 and, consistent with WHO recommendations, emphasize the importance of respect for victims' rights.Citation23–26 However, the guidelines differed in content and specificity, and facilities assessment found that they had not been widely disseminated (only six of the 34 facilities had a written copy of the guidelines on-site, and they were not being fully implemented.

After we had completed data collection, revised sexual violence guidelines were issued in El Salvador (2010),Citation28 Guatemala (2009),Citation29 and Nicaragua (2009).Citation30 Key changes in these guidelines are described below.

Violence detection and documentation

Screening

In practice, less than half (n=13) of the health care facilities assessed in this study indicated that they screened women for gender-based violence and only two used a specific screening tool. However, the guidelines from El Salvador and Nicaragua recommend that health care providers selectively screen women and children for violence if they suspect that an individual has been victimized.Citation23,25 Guatemala's family violence guidelines also recommend selective screening,Citation26 but their sexual violence guidelines do not include screening recommendations, most likely because these guidelines are focused on victims who seek emergency care after sexual assault.Citation24

Reporting to legal authorities

In each of the study countries, criminal laws oblige health care providers to report cases of sexual violence to the legal authorities, but exceptions are allowed in cases where providers feel obliged to maintain patient – provider confidentiality.Citation31–34 The Honduran criminal law does not make this exception. In contrast, the health system guidelines of El Salvador,Citation23 Guatemala,Citation24,26 and Nicaragua,Citation25 also require health service providers to report cases of sexual violence to the legal authorities but with no opt-out provisions. Nicaragua's guidelines state that providers must contact legal authorities when the victim is less than 18 years old, but do not state whether reporting is required for adult victims.

Registry of cases for surveillance purposes

El Salvador's guidelines provide a specific form for documenting cases, but do not describe providers' obligations or procedures for registering cases for surveillance purposes.Citation23 Guatemala's family violence guidelines state that health care providers should register cases,Citation26 but their sexual violence guidelines do not.Citation24 In contrast, Nicaragua's guidelines clearly require health care providers to register cases for surveillance purposesCitation25 and include a form for documenting cases.

We did not specifically assess whether the 34 facilities registered sexual violence cases for surveillance purposes. However, reports based on national-level data suggest that surveillance systems are unreliable and may be under-utilized. For example, in El Salvador in 2010 the Institute for Legal Medicine registered 3,382 cases of sexual aggression (1,793 were cases of rape), whereas for the same year the Ministry of Health registered only 152 cases of sexual violence.Citation35 Data suggest similar discrepancies in the number of cases reported by justice vs. health sector institutions in Nicaragua and Guatemala.Citation36–38 Individuals who seek services from the Institute for Legal Medicine may choose not to seek health services, and referral mechanisms from Legal Medicine to health services may be inadequate. It is also possible that health care providers are failing to register cases of sexual violence due to lack of motivation, knowledge and/or poor system usability.

Documentation in medical records

Comprehensive documentation of consultations with victims of sexual violence by health care providers is essential for ensuring appropriate care and may be crucial for obtaining legal redress.Citation21 Guidelines in El Salvador,Citation23 Guatemala,Citation24 and Nicaragua,Citation25 instruct providers to obtain and record a medical history and perform a physical examination. Consistent with WHO recommendations,Citation21 these guidelines state that providers should prioritize medical stabilization and support of victims over the collection of forensic evidence.Citation23–25 El Salvador's and Guatemala's guidelines specify the elements that should be included in a medical history (e.g. an account of the sexual assault) and procedures for documenting injuries.Citation23,24

Our facilities assessment found that medical records related to sexual violence were generally of poor quality. Only nine facilities indicated that they used a standard examination form for documenting sexual violence cases; the remainder used generic forms for taking a clinical history or a blank piece of paper. The medical records that were reviewed generally included only basic information about the patient and lacked important details of their medical history (e.g. current medications, description of injuries, treatment such as emergency contraception, and referral for specialized care).

We were also unable to obtain reliable information from the facilities as to how many women were being provided with sexual violence services monthly.

Forensic examination

Health care providers are uniquely placed to document and collect evidence necessary for identifying perpetrators and providing evidence of the circumstances of an assault.Citation21 Effective treatment guidelines should specify providers' responsibilities in the documentation of patient histories, collection of forensic evidence, and coordination with justice institutions. In each of the four study countries, government-run Institutes of Legal Medicine (or in Honduras the Forensic Medicine Department in the Public Ministry) have historically been responsible for forensic examination, analysis of specimens, and producing medico-legal reports for use in judicial proceedings. However, Nicaraguan law (2005)Citation39 also explicitly allows for medico-legal examinations be provided by court-certified specialists who are not employees of Institutes of Legal Medicine.

Health systems guidelines vary in the specificity and clarity of their instructions with respect to providers' role in the collection of forensic evidence and coordination with legal authorities. Guatemala's sexual violence guidelines state that providers should conduct a physical exam that has the “dual purpose of evaluating patient health and collecting forensic evidence that may be used to prove when, how and who attacked the patient.”Citation24 Explicit instruction is provided as to how to collect forensic specimens, and providers are tasked with “maintaining the chain of evidence,”Citation24 but no guidance is provided as to when or how providers should do this themselves or how to coordinate with the Institute of Legal Medicine. El Salvador's guidelines state that health care providers are not authorized to collect forensic evidence and that the Institute of Legal Medicine is responsible for this,Citation23 but again no guidance is given about coordination with the justice sector or what to do if it is not feasible for the woman to access these services. Similarly, Nicaragua's guidelines state that court-certified forensic specialists are responsible for forensic examination, but no further guidance is provided.Citation25

In practice, health professionals interviewed during the facilities assessment indicated that they would treat the immediate medical and psychological needs of victims of sexual violence and then refer them to the Institute for Legal Medicine for forensic examination and evidence collection. In a few instances, they said informally that they preferred to refer victims of sexual violence to the Institute for Legal Medicine for forensic evaluation prior to performing a physical examination themselves, because they wished to avoid the risk of contaminating forensic evidence or becoming involved in the legal process at all. Only three facilities were able to provide forensic services on site because they had court-certified forensic doctors on staff.

Treatment, referral and follow-up care

The comprehensiveness of guideline content regarding medical treatment, referral and follow-up care varied. In Honduras, guidelines were limited to a simple list of services that should be provided to adolescent victims of sexual violence.Citation27 In contrast, guidelines from El Salvador,Citation23 Guatemala,Citation24 and NicaraguaCitation25 were more detailed and emphasized that service providers should be appropriately trained and respect victims' rights.

The 34 facilities assessed were staffed by at least one doctor and the majority also employed at least one nurse (88%), and/or a psychologist (68%). The majority had adequate space with auditory (76%) and visual (79%) privacy, but only 47% had adequate toilet facilities. In general, better infrastructure for patient examination was found at the NGO/private facilities as compared to the public facilities.

Treatment

With respect to medical treatment, Nicaragua's guidelines said generally that providers should attend to victims' health care needs, including psychological needs,Citation25 while Guatemala's and El Salvador's guidelines had explicit instructions for examination of victims; treatment of injuries; pregnancy testing and providing emergency contraception; testing and treatment for STIs/HIV; and psychological support. Guatemala's guidelines also advised obtaining informed consent for examination and treatment.Citation24 None of the guidelines addressed options for women who became pregnant as a consequence of rape, as none of the study countries allowed legal abortion on this ground.

Most of the 34 facilities had analgesics and antibiotics available on-site, but only 59% stocked emergency contraception. Very few facilities were stocked with hepatitis B vaccine (3%) or HIV prophylaxis (38%) and only 68% reported having pregnancy tests available (Table 3).

Referral

If victims of sexual violence seek services at a facility that cannot provide comprehensive care, they should be referred to a facility that can. El Salvador's guidelines only applied to secondary and tertiary hospitals, as they were likely to have the capacity to provide comprehensive care; nothing was found that applied to primary care facilities. Nicaragua's and Guatemala's guidelines state that victims should be referred for specialized care, but do not establish a specific referral protocol. All of the guidelines mention the importance of referral for on-going psychological support, social services and legal aid. Consistent with WHO recommendations,Citation21 the Nicaraguan and Guatemalan (2006) guidelines also recommend that facilities maintain a contact list of local organizations to which victims may be referred for these services.Citation24,25 However, only 62% of the 34 facilities assessed indicated they provided referral or on-site psychosocial support services and counselling, and only 26% provided on-site services or referral for legal aid; all of these were private sector NGOs (Table 3).

Follow-up care

All of the guidelines stated that providers should arrange for follow-up care, but only the El Salvador guidelines stated specifically that victims should be scheduled for a one-week check-up with the same provider that initially evaluated them.Citation23

Discussion

Since early 2009, when this study was completed, health sector guidelines for the treatment of victims of sexual violence have been revised and updated in El Salvador (2010),Citation28 Footnote* Guatemala (2009),Citation29 and Nicaragua (2009).Citation30 UNFPA are providing technical assistance to the Health Secretariat of Honduras to develop and pilot new guidelines on sexual violence.Citation40

Table 2 identifies subject areas where these new guidelines differ from the guidelines in use when we were collecting data (in italics). In general, these guidelines had been strengthened as regards documentation, referral and follow-up. In particular, all three guidelines now clearly describe documentation procedures and referral protocols for primary care facilities, and include specific instructions for follow-up care. The updated Nicaraguan guidelines also include comprehensive instructions on whether and when forensic evidence should be collected.Citation30

Our findings provide a snapshot of service delivery in a small sample of facilities that were not randomly selected, and our conclusions cannot be generalized across or within countries. Only two facilities were located in rural areas where access to external psychosocial and legal services was most likely very limited. We did not examine provider training, attitudes or practices, nor the perspectives of victims of sexual violence who received care or barriers to accessing care. In addition, we were unable to obtain statistics on the case loads or types of services actually provided to victims of sexual violence in the facilities we assessed.

Despite these limitations, however, this study demonstrates the commitment of four Central American governments and civil society to developing health sector policies that support the provision of health care services to victims of sexual violence. All four countries we studied currently have or are developing protocols for the treatment of victims of sexual violence with some variation in their provisions.

Nonetheless, data from the region suggest that only a small proportion of women who experience sexual violence actually seek care, due to barriers such as lack of trust in government authorities.Citation2–6 The challenge facing these countries is that of turning policy into practice. In particular, health care authorities in each country will need to ensure that policies are disseminated, providers are adequately trained in their implementation, resources are available to equip facilities, and implementation is initiated, monitored and evaluated.

Stakeholders from the legal, justice and civil sectors should be engaged in the implementation process as well, to ensure a coordinated response. Within the health sector, administrators and providers will need to be provided with training and resources that will enable implementation.

Recommendations

Although health sector guidelines generally recommended some form of screening for sexual violence, screening practices were inconsistent. Routine screening for sexual assault may identify and provide help to victims who might not otherwise disclose that they were victimized. However, researchers have cautioned that routine screening may do more harm than good if resources are not available to provide a response and/or providers respond to disclosure inappropriately.Citation41 As screening policies begin to be implemented in these countries, health care authorities should take steps to ensure that the risks associated with screening are low and address any provider beliefs that may deter screening (e.g. screening will take too much time or lead to entanglement in a complicated legal process).Citation41

The requirement that providers report cases of sexual violence to legal authorities may violate women's right to privacy if they do not wish the assault to be reported. Current guidelines in the four countries make no explicit provisions for obtaining victims' permission and/or abstention to safeguard confidentiality. Proponents of mandatory reporting argue that it helps prevent sexual violence by holding perpetrators accountable, whereas opponents argue that it violates privacy rights, may lead to more violence and deter help-seeking. Future research should examine the potential risks involved. Policy-makers may consider adopting anonymous reporting protocols, in which health care and evidence collection are prioritized, but not necessarily investigation of all cases.Citation42

Our findings strongly suggest that policies and systems for registering cases of sexual violence need to be strengthened. Documentation of cases of sexual violence is a vital part of efforts to understand the magnitude of the problem and monitor and evaluate prevention efforts, yet Nicaragua is the only study country that clearly requires recording of cases for surveillance purposes. Available data suggest that across the region there is a large discrepancy in the number of cases registered by legal and health system institutions.Citation35–38

Finally, policies should more clearly indicate the roles and responsibilities of health care providers and forensic specialists in the collection of forensic evidence. Our findings suggest that the health and medico-legal components of care are often provided at different times, in different places, and by different people. As noted by WHO, this is both inefficient and burdensome to victims.Citation27 There are good examples of provision of a range of services for victims of sexual violence (including forensic services) at a single location, which, if replicated, might well lead more women to come forward for care and support (e.g. the Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner model and Sexual Assault Response Teams).Citation43

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Agencia Española de Cooperación Internacional para el Desarrollo, United Nations Population Fund, and Ipas. Health care policies and facilities data from the study have been described in Spanish-language country reports at: http://www.ipas.org/en/Resources.aspx. For this paper, these data were translated and analysed from a regional perspective.

Notes

* Men and boys also experience sexual violence, though there is very little research on this issue in the region.Citation6 This study focuses on sexual violence against adult women and policy guidelines and care provided to them, because that is the current focus of national and international policy. Other international and national laws and policies address child sexual abuse.

* The new Salvadorean guidelines apply to all health care facilities, not just secondary and tertiary hospitals.

References

- EG Krug, LL Dahlberg, JA Mercy. World report on violence and health. 2002; World Health Organization: Geneva. At: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2002/9241545615_eng.pdf. Accessed 19 March 2012.

- Ministry of Health and Social Assistance (Guatemala), University of Valle (Guatemala) and Division of Reproductive Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guatemala Reproductive Health Survey 2008–2009. Atlanta, GA: CDC. At: http://www.healthmetricsandevaluation.org/sites/default/files/record-attached-files/GTM_RHS_2008_2009_REPORT.zip. Accessed 5 September 2012.

- National Institute for Development Information (Nicaragua), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nicaragua Reproductive Health Survey 2006–2007. Managua: National Institute for Development Information (Nicaragua), Ministry of Health (Nicaragua). At: http://www.healthmetricsandevaluation.org/sites/default/files/record-attached-files/NIC_RHS_2006_2007_REPORT.zip. Accessed 5 September 2012.

- Salvadoran Demographic Association Division of Reproductive Health Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. El Salvador Reproductive Health Survey 2008. 2009; ADS: San Salvador. At: http://www.healthmetricsandevaluation.org/sites/default/files/record-attached-files/SLV_RHS_2008_REPORT.zip. Accessed 5 September 2012.

- Ministry of Health (Honduras), National Institute of Statistics (Honduras), Macro International, Inc. Honduras Demographic & Health Survey 2005–2006. Calverton, MD: Macro International, Inc. At: http://www.measuredhs.com/pubs/pdf/FR189/FR189.pdf. Accessed 5 September 2012.

- JM Contreras, S Bott, A Guedes. Sexual violence in Latin America and the Caribbean: A desk review. At: http://www.svri.org/SexualViolenceLACaribbean.pdf. Accessed 5 September 2012.

- Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women adopted by the UN General Assembly on 18 Dec 1979; entered into force 3 September 1981 (1249 U.N.T.S. 13). At: http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/cedaw/text/econvention.htm. Accessed 5 September 2012.

- Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment and Eradication of Violence Against Women “Convention of Belem do Para” adopted in Belem do Para, Brazil, adopted by the General Assembly of the Organization of American States on June 9, 1994. At: http://www.cidh.org/Basicos/English/basic13.Conv%20of%20Belem%20Do%20Para.htm. Accessed 5 September 2012.

- C Garcia-Moreno, HAFM Jansen, M Ellsberg. WHO Multi-Country Study on Women's Health and Domestic Violence against Women. 2005; WHO: Geneva. At: http://www.who.int/gender/violence/who_multicountry_study/summary_report/summary_report_English2.pdf. Accessed 5 September 2012.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Crime and Development in Central America: Caught in the Crossfire. 2007; UNODC. At: http://www.unodc.org/pdf/research/Central_America_Study_2007.pdf

- L Breur, A Cruz. The political economy of implementing pro-growth and anti-poverty policy strategies in Central America. M Rodlauer, A Schipke. Central America: Global Integration and Regional Cooperation. 2005; International Monetary Fund. 125–133. At: http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/op/243/243ch8.pdf. Accessed 19 March 2012.

- World Health Organization. Preventing intimate partner and sexual violence against women: taking action and generating evidence. 2010; WHO: Geneva. At: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241564007_eng.pdf. Accessed 5 September 2012.

- República de El Salvador. Código Penal de El Salvador Comentado, Tomo 1, Titulo IV, Capítulo 1, Artículo 158. At: http://www.cnj.gob.sv/index.php?view=article&catid=42:publicaciones&id=116:codigo-penal-de-el-salvador-comentado-&option=com_content&Itemid=12. Accessed 19 March 2012.

- República de Guatemala. Código Penal de Guatemala, Titulo III, Capítulo 1, Artículo 173. At: http://www.oas.org/juridico/mla/sp/gtm/sp_gtm-int-text-cp.pdf. Accessed 19 March 2012.

- República de Honduras. Código Penal de Honduras, Titulo II, Capítulo 1, Artículo 140. At: http://www.poderjudicial.gob.hn/juris/Leyes/Codigo%20Penal%20(actualizada-07).pdf. Accessed 19 March 2012.

- República de Nicaragua. Código Penal de Nicaragua, Libro II, Titulo 1, Capítulo VIII, Artículo 195. At: http://www.oas.org/juridico/mla/sp/nic/sp_nic-int-text-cp.html. Accessed 5 September 2012.

- Interamerican Commission on Human Rights. Access to Justice for Women Victims of Sexual Violence in Mesoamerica. No. 11. Organization of American States; 2011. At: http://www.oas.org/en/iachr/women/docs/pdf/WOMEN%20MESOAMERICA%20ENG.pdf

- United Nations Population Fund. Cerrando brechas de equidad para avanzar hacia el acceso universal a la salud reproductiva en 13 países de América Latina y el Caribe. At: http://lac.unfpa.org/webdav/site/lac/shared/DOCUMENTS/2011/Peru%202011%20AECID/2406_UNFPA-Bro-Ins-17%283%29.pdf. Accessed 19 March 2012.

- United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women. Ending violence against women and girls: programming essentials. At: http://www.endvawnow.org/uploads/modules/pdf/1328563919.pdf. Accessed 5 September 2012.

- E Troncoso, DL Billings, O Ortiz. Ver y atender! Guía práctica para conocer como funcionan los servicios de salud para mujeres víctimas y sobrevivientes de violencia sexual. 2006; Ipas: Chapel Hill, NC. At: http://www.ipas.org/media/Files/Ipas%20Publications/SVGUIDEE08. Accessed 5 September 2012.

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for the medico-legal care of victims of sexual violence. 2003; WHO: Geneva. At: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2004/924154628X.pdf. Accessed 19 March 2012.

- M Velzeboer, M Ellsberg, C Clavel Arcas. Violence against women: the health sector responds. 2003; Pan American Health Organization: Washington, DC.

- Ministerio de Salud de El Salvador. Guías de atención clínica a mujeres y personas menores de edad víctimas de violencia intrafamiliar y sexual para hospitales del segundo y tercer nivel. 2007; MINSAL: San Salvador. At: http://asp.mspas.gob.sv/regulacion/pdf/guia/guia_victimas_VIF_y_sexual_p1.pdf. (Part 1) andhttp://asp.mspas.gob.sv/regulacion/pdf/guia/guia_victimas_VIF_y_sexual_p2.pdf. (Part 2). Accessed 19 March 2012.

- Ministerio de Salud Pública y Asistencia Social de Guatemala. Protocolo de atención a víctimas de violencia sexual. 2006; MSPAS: Guatemala.

- Ministerio de Salud de Nicaragua. Normas y protocolos para la prevención, detección, y atención de la violencia intrafamiliar y sexual. 2006; MINSA: Managua.

- Ministerio de Salud Pública y Asistencia Social de Guatemala. Protocoló de atención a víctimas de violencia intrafamiliar. 2008; MSPAS: Guatemala.

- Manual de normas para la atención integral de los y las adolescentes. 1997; Secretaria de Salud de Honduras: Tegucigalpa.

- Ministerio de Salud de El Salvador. Lineamientos técnicos de atención integral a todas las formas de violencia. 2010; MINSAL: San Salvador.

- Ministerio de Salud Pública y Asistencia Social de Guatemala [MSPAS]. Protocolo de atención a víctimas/sobrevivientes de violencia sexual. 2009; MSPAS: Guatemala.

- Ministerio de Salud de Nicaragua. Normas y protocolos para la prevención, detección, y atención de la violencia intrafamiliar y sexual. 2009; MINSA: Managua.

- República de El Salvador. Código Procesal Penal de El Salvador, Libro Segundo, Titulo 1, Capítulo 1, Artículo 232. At: http://cnj.gob.sv/index.php?view=article&catid=42%3Apublicaciones&id=117%3Acodigo-procesal-penal-de-el-salvador-comentado&option=com_content&Itemid=12. Accessed 19 March 2012.

- República de Guatemala. Código Procesal Penal de Guatemala, Capítulo III, Artículo 298. At: http://www.oas.org/juridico/MLA/sp/gtm/sp_gtm-int-text-cpp.pdf. Accessed 19 March 2012.

- República de Honduras. Código Procesal Penal de Honduras, Titulo III, Capítulo 1, Artículo 269. At: http://www.poderjudicial.gob.hn/juris/Leyes/CODIGO%20PROCESAL%20PENAL.pdf. Accessed 19 March 2012.

- República de Nicaragua. Código Procesal Penal de Nicaragua, Titulo 1, Capítulo 1, Artículo 223. At: http://legislacion.asamblea.gob.ni/Normaweb.nsf/($All)/5EB5F629016016CE062571A1004F7C62?OpenDocument. Accessed 19 March 2012.

- D Luciano, K Padilla. Violencia sexual en El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras y Nicaragua: Análisis de datos primarios y secundarios. 2012; Ipas Centroamérica: Managua.

- Corte Suprema de Justicia de Nicaragua. Instituto de Medicina Legal. Anuario 2009. At: http://www.poderjudicial.gob.ni/pjupload/iml/pdf/ml_anuario_2009.pdf. Accessed 12 September 2012.

- Ministerio de Salud de Nicaragua. Oficina Nacional de Estadísticas. Análisis estadístico de la situación de salud en Nicaragua 2000–2011. At: http://www.conexiones.com.ni/files/79.pdf. Accessed 12 September 2012.

- CIMAC Noticias. En Guatemala, subregistro en los casos de violencia sexual. August 2009. At: http://www.cimacnoticias.com.mx/site/09081801-En-Guatemala-subre.38984.0.html. Accessed 12 September 2012.

- Corte Suprema de Justicia. Protócolo de Actuación en Delitos de Maltrato Familiar y Agresiones Sexuales. 2003; Guía para personal Policial, Fiscal, Médico-Forense y Judicial: Managua.

- Fondo de Población de las Naciones Unidas. Salud y justicia para mujeres ante la violencia sexual en Centroamérica. At: http://aecid.lac.unfpa.org/webdav/site/AECID/shared/files/Una%20mirada%20completa_Iniciativa4.pdf. Accessed 12 March 2012.

- S Bott, A Guedes, M Claramunt. Improving the health sector response to gender based violence: a resource manual for health care professionals in developing countries. 2010; International Planned Parenthood Federation.

- S Garcia, M Henderson. Options for reporting sexual violence: developments over the past decade. FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin. At: http://www.fbi.gov/stats-services/publications/law-enforcement-bulletin/May-2010/options-for-reporting-sexual-violence. Accessed 12 September 2012.

- L Harris, J Freccero. Sexual Violence: Medical and Psychosocial Support. Sexual Violence & Accountability Project Working Paper. 2001; Human Rights Center: University of California, Berkeley. At: http://www.law.berkeley.edu/HRCweb/pdfs/SVA_MedPsych.pdf. Accessed 19 March 2012.