Abstract

Gynaecological cancers are the fourth most common form of cancer and the fifth most common cause of cancer mortality for women in Australia. Definitive treatment is available in tertiary hospitals in major capital cities. This study aimed to understand how care is received by women in order to improve both their experience and outcomes. We interviewed 25 women treated for ovarian, cervical and uterine cancers in public or private hospitals in four states, including urban, rural and Indigenous women. Referral pathways were efficient and effective; the women were diagnosed and referred for definitive management through well-established systems. They appreciated the quality of treatment and the care they received during the inpatient and acute phases of their care. Three main problems were identified – serious post-operative morbidity that caused additional pain and suffering, lack of coordination between the surgical team and general practitioners, and poor pain management. The lack of continuity between the acute and primary care settings and inadequate management of pain are acknowledged problems in health care. The extent of post-operative morbidity was not anticipated. Establishing links between the surgical team and primary care in the immediate post-operative period is crucial for the improvement of care for women with gynaecological cancer in Australia.

Résumé

En Australie, les cancers gynécologiques sont la quatrième forme de cancer en termes de fréquence et la cinquième cause de mortalité par cancer chez les femmes. Un traitement définitif est disponible dans les hôpitaux tertiaires des principales capitales d'États et territoires. Cette étude souhaitait comprendre comment les soins sont reçus par les femmes pour améliorer leurs expériences et les résultats. Nous avons interrogé 25 femmes urbaines, rurales et aborigènes traitées pour un cancer des ovaires, du col de l'utérus et de l'utérus dans des hôpitaux publics ou privés de quatre États. Les filières d'aiguillage des patientes étaient efficaces ; les femmes étaient diagnostiquées et orientées pour une prise en charge définitive par des systèmes bien établis. Elles appréciaient la qualité du traitement et des soins reçus pendant les hospitalisations et les phases aigües des soins. Trois principaux problèmes ont été identifiés : la morbidité post-opératoire qui causait des douleurs et des souffrances supplémentaires, le manque de coordination entre l'équipe chirurgicale et les médecins généralistes, et la médiocre gestion de la douleur. Le manque de continuité entre les services de soins aigus et primaires, et la prise en charge insuffisante de la douleur sont des problèmes connus des soins de santé. L'ampleur de la morbidité post-opératoire n'était pas prévue. Pour améliorer les soins des femmes présentant un cancer gynécologique en Australie, il est essentiel d'établir des liens entre l'équipe chirurgicale et les soins primaires immédiatement après l'intervention.

Resumen

El cáncer ginecológico es el cuarto tipo más común de cáncer y la quinta causa más común de mortalidad por cáncer de las mujeres en Australia. En las principales capitales, se ofrece tratamiento definitivo en hospitales terciarios. El objetivo de este estudio fue entender cómo los servicios son recibidos por las mujeres con el fin de mejorar tanto su experiencia como los resultados. Entrevistamos a 25 mujeres, urbanas, rurales e indígenas, atendidas por cáncer ovárico, cervical y uterino, en hospitales públicos o privados de cuatro estados. Las vías de referencia fueron eficientes y eficaces; las mujeres fueron diagnosticadas y remitidas para manejo definitivo por sistemas bien establecidos. Ellas agradecieron la calidad del tratamiento y los cuidados que recibieron durante las fases de internación y atención aguda. Se identificaron tres problemas principales: morbilidad postoperatoria adversa, que causó dolor y sufrimiento adicionales, falta de coordinación entre el equipo quirúrgico y los médicos generales y deficiente manejo del dolor. La falta de continuidad entre los ámbitos de atención aguda y primaria y el manejo inadecuado del dolor son problemas reconocidos en los servicios de salud. No se previó el grado de morbilidad postoperatoria. Para mejorar los servicios que reciben las mujeres con cáncer ginecológico en Australia es de importancia fundamental establecer vínculos entre el equipo quirúrgico y la atención primaria en el período postoperatorio inmediato.

Women's reproductive health includes gynaecological cancers, although this link is made rarely. Reproductive Health Matters drew attention to this deficit in 2008 when it focused primarily on cervical and breast cancer.Citation1 This article covers uterine, ovarian and cervical cancer, its diagnosis, management and outcomes in a well-resourced health system.

About 27% of Australia's population of 23 million live in regional (large rural towns), rural or remote areas in a land mass nearly the size of Europe.Citation2 Delivery of health services to these areas is a continual challenge.

Efforts to improve the quality of cancer care in Australia have been supported by significant government attention since 2005. The National Service Improvement Framework for Cancer is driving improvements in health service delivery.Citation3–9 Cancer is one of the five national priority health areas and the Framework provides policy guidelines for health planners and professionals. It is structured to reflect the patient journey from reducing risk, early detection, management of the acute phase, long-term care and terminal care.

Gynaecological cancers are the fourth most common form of cancer for women in Australia and the fifth most common cause of cancer mortality. In 2007 the age standardised incidence of uterine cancer was 16.5 per 100,000 women, 10.8 for ovarian cancer and 6.8 for cervical cancer.Citation10 The risk of uterine cancer by age 85 in Australia was 1 in 50, ovarian cancer 1 in 78, and cervical cancer 1 in 158.Citation11 Gynaecological cancers accounted for 8.5% of all female cancer deaths and ovarian cancer was in the top ten most common causes of cancer deaths in women, with an incidence of 7 deaths per 100,000.

The incidence of cervical cancer was significantly higher for Indigenous than non-Indigenous Australians.Citation10 There is a comparatively high rate of gynaecological cancers among Indigenous women, particularly those living in remote and rural regions. Lack of access to primary care because of poverty, shortage of services, distance and cultural barriers makes it difficult for Indigenous women to receive screening, diagnosis and treatment for gynaecological cancers.Citation12

Geography did not influence survival from uterine cancer between 2003 and 2007,Citation13 but five-year survival for ovarian cancer decreased with increasing remoteness from 45% in major cities to 36% in outer regional areas. Five-year survival for cervical cancer was 74% in major cities but only 58% in remote and very remote areas.Citation13

If cancer of the uterus is detected early, 70–95% of women survive at least five years, and most are cured.Citation14 If ovarian cancer is treated when it is still confined to the ovaries, 93% of women will be alive in five years. If the cancer has spread to surrounding tissue or organs in the pelvis, this drops to 39%. Cervical cancer is easier to diagnose than uterine or ovarian cancer, and treatment is effective.Citation10 To have a chance of survival women require timely diagnosis and extensive surgical excision of the cancer, which may involve other structures such as the bladder and bowel. The intensity of treatment contributes to the stress of the experience and has been shown to lead to post-traumatic stress disorder.Citation15 A UK study found that six months after treatment for gynaecological cancer women still had an average of four major concerns relating to illness, treatment and outcomes.Citation16

Australia has a well-developed health care system and universal health insurance that ensures all citizens can access essential medical care without cost being a major barrier. Gynaecological surgical care is provided in tertiary hospitals, all of which are located in major cities. In 2011 the number of skilled surgeons was small – 45 specialist gynaecological oncologists (12 women) and seven gynaecologists training in the sub-specialty (3 women) (Royal Australasian College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, Personal communication, September 2012). Surgeons interviewed in 2008 reported being overworked and tired.Citation17

General practitioners comprise the bulk of the medical workforce distributed throughout Australia. Women living in regional and rural areas are dependent on general practitioners for referral for curative surgical care and for post-operative management.

There are 157 regional hospitals that administer chemotherapy, out of 761 public hospitals and 543 private hospitals. Rural people are more likely to die of cancer within five years of diagnosis than urban people and restricted access to care contributes to this.Citation18

This qualitative study of the experiences of women receiving gynaecological cancer treatment adds the voice of women to the national discussion about cancer care, identifying strengths and gaps in services.

Method

This was an empirical case study with data from in-depth, semi-structured interviews with 25 women who had been treated for any type of gynaecological cancer. A purposive sample was recruited from five cancer treatment centres in Victoria, New South Wales, South Australia and the Northern Territory during 2008, and one consumer representative. These centres were selected for variation in geographic location (metropolitan-regional-rural) and included both public and private hospitals. This was the maximum number and variation of women we could recruit within the resources of the study. Inclusion criteria were having received treatment for gynaecological cancer. Exclusion criteria were being too ill to take part or unable to provide informed consent. The interviews with the Indigenous women are also reported elsewhere.Citation12

Interviewing women about the quality of treatment was a delicate exercise. An opt-in model was used to recruit participants from treatment clinics. Staff handed out an information flyer inviting women to make direct contact with the research team, who were independent of the treatment team. Those who contacted us were invited to take part in an interview. The decision to participate or not was not known to the treatment teams. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the ethics committees of the five treatment centres, and two universities.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted face-to-face (n=19) or by telephone (n=6) taking 60–90 minutes.Citation19 Women were asked to begin with the story of how they found out about their cancer. They were asked about their experiences of the care provided by medical, nursing and allied health professionals, and outcomes of treatment. All interviews were audio recorded with permission and were transcribed by a professional service. Thematic analysis of transcripts was carried out using NVivo8 qualitative analysis software.Citation20 This software is based on Grounded Theory, in which data themes are generated from the data rather than a priori.Citation21 Approximately 10% of the data were analysed independently by two members of the team and checked for variation in interpretation.

Findings concentrate on diagnosis, access and outcomes of care. Codes in brackets with quotes specify each woman by a number and R (for rural), U (for urban) and I (for Indigenous). Patient stories are taken from interview transcripts. They have been shortened and modified to ensure intelligibility and remove identifying information but remain faithful to the original text.

Findings

Seventy-four women were approached for the study. Of the 68 who were eligible, 30 agreed to take part, of whom 25 were interviewed. The sample included 12 urban, 4 regional and 9 rural women. Three of the rural women were Indigenous. Rural woman and Indigenous women were specifically sought for the study, rural women by recruitment from rural clinics, and Indigenous women who were contacted by an Indigenous researcher. Twenty of the women were treated in a public hospital (5 urban Victoria, 6 rural New South Wales, 2 urban South Australia, 4 regional Northern Territory, 3 Aboriginal rural South Australia), and five in a private hospital (4 urban South Australia, 1 urban New South Wales).

Ten of the women had uterine cancer, seven ovarian cancer and eight cervical cancer; all but three were primary cancers. Six were diagnosed more than five years prior to the study, 16 one to five years previously, and three less than a year before. Their average age at interview was 58, with one woman aged less than 30 and three aged 71–85. Sixteen of the women were married, five divorced, three widowed, one single, and all but three had children. Eight were living alone.

Pathways to care

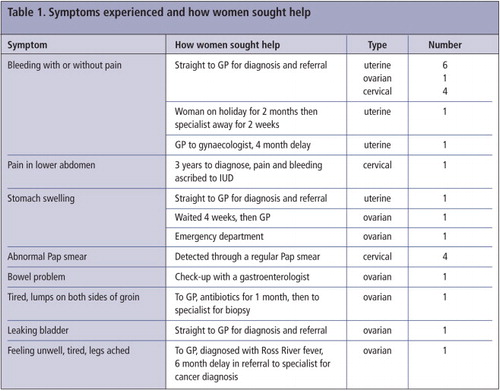

The primary care system worked well for most women. The diagnostic journey started either with a routine Pap smear or symptoms that prompted them to consult their general practitioner. Gynaecological cancer can be difficult to diagnose because there may be no symptoms, or symptoms may not be specific to cancer. Symptoms reported by the women included pain in the bladder, lower abdomen, bowel and chest, painful sexual intercourse, bleeding from the vagina, swelling of the abdomen, lumps in the groin and a generalised feeling of being unwell associated with leg pain.

Most women went from diagnosis to treatment in a well-oiled system that took care of them each step of the way. Urban women were more likely than rural women to be referred directly to a gynaecological oncologist (5 urban, 1 rural). Regional and rural women had more complex pathways to diagnosis, intervention, and post-intervention care than urban women, largely as a result of variations in service availability in rural areas.

Most of the women sought immediate help when they experienced symptoms.

The time between presentation with symptoms and diagnosis was short, with nine women being diagnosed within two days and another five within two weeks of seeing their doctor (Table 1). Four women had no symptoms and were diagnosed at routine Pap smear (two others had had recent normal smears). Three women were misdiagnosed and treatment was delayed, with serious consequences. It took one woman three years to obtain a diagnosis of cancer despite repeat visits to a family planning clinic. By that time the cervical adenocarcinoma had spread and required radical surgery. At the time of interview ovarian cancer had been identified and she was due for further surgery. Another woman had equivocal pathology findings for cervical cancer that led her to agree to a hysterectomy after eight months. In an attempt to preserve her hormone function, in case radiotherapy was required, her ovaries were moved to the front of her abdomen. At operation, it was found that she did not have cancer.

For most women, the general practitioner made a provisional diagnosis of gynaecological cancer and referred her to a gynaecologist and/or a gynaecological oncologist for investigation, confirmation of diagnosis and treatment. Twenty-four women had a radical hysterectomy regardless of type of cancer and one had a radical trachelectomy (excision of the cervix). An additional surgeon was involved for five of the women. Follow-up treatment included chemotherapy, radiotherapy including brachytherapy (radiation pellets delivered to the site of the tumour), or both. Most women were followed up by the treating surgeon, and 19 had a general practitioner for general health care, of whom 14 were involved in follow-up cancer care after treatment. The six who did not have post-operative care with a general practitioner were managed by hospital teams, a gynaecological oncologist or gynaecologist. Treatment teams were similar for the three types of cancer.

One woman was immunosuppressed as the recipient of an organ transplant, another developed ovarian cancer secondary to abdominal cancer with involvement of the bowel, a third had bowel cancer identified at surgery, and another had uterine cancer associated with cancer of the stomach. One woman with ovarian cancer as a primary diagnosis also had primary Hodgkins lymphoma treated with chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

Seven women had a hysterectomy without further treatment. The seven women with ovarian cancer all had chemotherapy, as did three with uterine cancer and one with cervical cancer. Two of the women with uterine cancer and two with cervical cancer had radiotherapy. Two women with uterine cancer had brachytherapy. The woman with ovarian cancer and Hodgkins lymphoma had both chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

All the women continued to be monitored monthly, three monthly or annually by their general practitioner, the gynaecological oncologist who performed the surgery, or a gynaecologist.

Access to treatment and cost

Access to health services was swift and appropriate for all women once a correct diagnosis had been made, although more difficult for rural women. Eighteen women had surgery within two weeks of diagnosis. One woman who was asymptomatic and diagnosed by Pap smear had her CIN3 result communicated to her only after a nine-month delay. For the remaining women, additional time was needed to organise care among the treatment team, or pre-operative chemotherapy or radiation therapy. Several women delayed treatment while they considered their options, and one took a long-planned holiday first. Almost all women commented favourably on the timeliness of care although a few found it difficult to assess the benefits of suggested therapies or surgery in the short time they were given.

The women who received all their care in the public system had few medical costs, while those who had private health insurance were left with out-of-pocket expenses linked to their level of health insurance. Costs ranged from a few hundred Australian dollars to more than A$5000 out-of-pocket expenses. Additional costs were incurred by those who had to travel, and in lost time from work for themselves and their partners.

Quality of care

The women defined quality care as care they could be confident in. This required a mixture of a positive attitude among staff, giving women hope of a good outcome, and confidence that the team members were efficient and knew what they were doing. The women appreciated the sense of safety that came with trust in their surgeon. They responded well to staff who kept their hope alive. Overall, the gynaecological workforce were seen to offer high quality patient-centred care, personal support, appropriate information and smooth transitions from one aspect of care to another, so that they felt their team were skillful and communicated both with each other and with them and their families.

The women developed a more intense therapeutic relationship with their doctor than with nurses or allied health professionals. Women spoke of their doctor and knew his or her name, while nurses were spoken of in very general terms and their names were not known.

Outcomes of treatment

Gynaecological cancer focuses on a woman's sexual functioning and body parts that define her as female. A radical hysterectomy removes these organs and involves parts of the body that are not usually spoken about, making normalisation of the experience through small talk unavailable. This can challenge a woman's sense of femininity and of being a whole person. A small number of women described feeling “dirty”, no longer a woman, sexually unattractive and doubtful about gender identity. Some women found the surgery very confronting, along with the sense of powerlessness, dependency, and being out of control of their lives, as well as the physical pain and difficulty. Even women who did not have adverse outcomes found the experience of diagnosis and treatment traumatic.

“It's a very scary experience because you go from finding something and then it's all blood tests and scans and ultrasound and then you go through major surgery and then the chemo and you're just bewildered.” (U5)

“You go in feeling extremely well and not really knowing there was anything wrong… and from then on your life becomes a bit of a misery because this doesn't work and the bowels won't work properly and all that stuff… When we did the operation the surgeon was really excited. ‘I've got it all’, he said, ‘and that's it.’ But, of course it isn't. That's not the full story and nobody knows what the full story is.” (U3)

Life after treatment and adverse events

Although the journey forward could be complicated, painful and difficult and the outcome uncertain, the moment of recovering from the surgery and being sent home, free of observable cancer, was a moment to be savoured. All but two of the women were in remission at the time of interview. One woman who was not in remission had had ovarian cancer that was excised, and a small tumour that was being monitored, the other had just been diagnosed with ovarian cancer at the time of interview and was awaiting further surgery. They were very conscious of the gift of extra life they had been given, and many dismissed the distress of the interventions as unimportant compared with that.

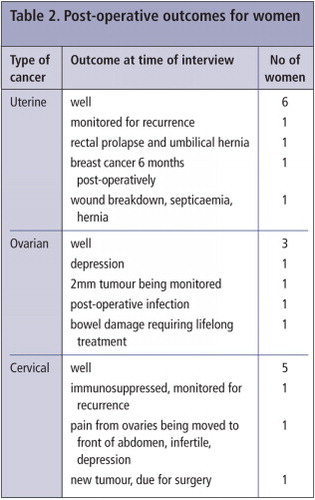

Eleven women had adverse outcomes after discharge from hospital that required further medical management; the others progressed as expected (Table 2). Two women had post-operative infections including a rural woman who became critically ill with septicaemia, two had debilitating depression, one had persistent inter-menstrual bleeding, one woman was dealing with a hernia four years later that was a result of the surgery, and another had a rectal prolapse and hernia. One woman with ovarian cancer experienced serious bowel complications. She required re-section and re-anastomosis of the bowel at the time of gynaecological surgery. She was told that the blood vessels were not joined properly, leading to initial paralysis of the bowel, severe constipation and pain. She was advised that this was a permanent condition and required lifelong medication (R1's story).

The woman who had a hysterectomy but turned out not to have cancer suffered persistent abdominal pain, as her ovaries (which had been moved) became surrounded by adhesions and a nerve was also involved. She was hospitalised as a result and was struggling with the impact on her marriage and her joy of life, because the only “solution” the surgeon could offer was to remove the ovaries, which she rejected. She is now extremely wary of mainstream medicine and appeared depressed, angry and sad.

An Aboriginal woman with cervical cancer had morphine apnoea during surgery and stopped breathing, with possible cardiac arrest, and had to spend time in intensive care recovering. She was admitted to hospital when she returned to her local community because of chest pain and concern about bowel obstruction (I1's story).

R1's story

R1 was age 61, married with 3 adult sons, living in a rural area 300 km from capital city. Left school at 15. Operated for ovarian cancer at a public hospital.

I must have had problems for probably six years before it was diagnosed and they just said it was the change of life. I had heavy bleeding. It was never like a severe pain, more like a small toothache. The pain was starting to annoy me and I had an ultrasound in June in 1999. The doctor rang me next day and said he felt that there was a tumour on the right ovary. From the minute that chap held the picture up to the window, he said to me ‘You're in trouble’. I still wasn't concerned because I wasn't sick. He said to me ‘You're going to have to go to (capital city)’. Because he could see that it was the ovary, tied up with the bowel as well. We were at (tertiary hospital 5 hours drive away) 2 weeks later and saw Dr X, I think she is God. Next day I had the operation, a total hysterectomy and 11 inches of bowel removed.

I was only there a week. Then they took the staples out. Dr X wasn't there and I saw someone else and we came home by car. This doctor told me that because I was leaving the hospital it was no longer anything to do with them. ‘When you get home you go and see your GP. If you have any problems you get in touch with your GP.’ When I got home I was extremely ill. My innards didn't work. Nothing worked. So when I rang my GP he promptly informed me that he had no idea what I'd had done. There was no paperwork. There was no follow up and he wouldn't make a house call and I was too sick to get out of bed. So I was in real strife. A week later I went over to the cancer clinic in (town across the state border) and that was when I got all the help. So for a week I just laid here and I was in real strife. I was in extreme pain, extreme. I had been so well in hospital and I felt like you were just dumped once you got home. Just no help at all.

I started the chemotherapy straight away. All the help and all the care and everything I got was just wonderful. Which it was in (capital city), too, it was just that awful week where there was no help, nothing. The chemo made me very sick and there were days when I just lay on the bathroom floor with my head in the toilet, so it was pretty ordinary.

Palliative care came about a month later. I opened the door and the lady said ‘I'm from palliative care’ and I said ‘But I'm not dying!’ I found the palliative care, the nursing side of it, they were wonderful, and we really only ever had to call on them once at night when I was in extreme pain from the chemo. That night they were here in next to no time and followed up with phone calls.

The pain was extreme, like contractions. See, I'm sort of cut right down here and because I was having all the pain there it was just terrible. They just tell you that's forever. The medication that I'm on is good but I can't ever stop the medication because once you stop you're in real trouble again. They feel it was because the blood vessels weren't joined up properly during the surgery. Quite a few of the people I've gone through with have passed away, so that makes me feel I was very lucky.

Discharged without ongoing care

A major negative finding was that some women were discharged from hospital without adequate ongoing care or information. Four women described the shock of getting home and not knowing what to do as the worst part of their experience. They felt too sick to manage and either could not get the help they needed, or struggled to do so. The shock of being left on their own after the intensive management in hospital was extreme. One woman's husband had to leave for work the morning after she got home, for example, and in spite of very bad pain she had to make food, take her insulin and look after herself, and felt completely helpless. “After he'd gone to work I just laid there and cried and I thought ‘What do I do?’” (U5)

Pain management

Effective and ineffective pain management occurred for both urban and rural women and in public and private hospitals. The women had different levels of need for pain relief, and good pain management mattered to them. When it went wrong, it left lasting effects.

Several women described not having pain or not being troubled by it, despite major surgery. Eighteen of the 25 women described their pain as being well managed. Even in a well-resourced health system such as Australia's, however, pain was not managed well for seven of the women, who experienced unnecessary and distressing pain associated with treatment and/or post-operatively.

The doctors were described as being very attentive to pain management, but some women struggled to get pain relief from nurses. One woman was very distressed when the staff would not believe her or respond when she said she was in pain. It took 20 minutes before a nurse realised the morphine drip tubing was kinked and no analgesia was getting through. Another woman endured an under-trained nurse trying to manage her epidural, and a doctor only intervened after 45 minutes, by which time the pain was extreme (U2's story).

Several women experienced pain during chemotherapy, which was well managed either by the chemotherapy unit, the general practitioner or the palliative care nurses.

Several women had significant complications and pain was a major issue for them. One woman was eventually hospitalised due to a bowel obstruction some time after her surgery for cervical cancer, after she had struggled to get the pain management she needed as an outpatient.

I1's story

I1, aged 64, Aboriginal, lives 600 km from city, lesbian partner, 1 son. Treatment for uterine cancer in private hospital.

I have a marvellous GP here who picked it up straightaway. I went in and told her the symptoms, that a couple of times in the supermarket I felt like a knife had gone through my left side. Then there were some telltale signs with pain and bleeding. A week later I was in theatre. I had CIN1, cancer of the uterus.

The nursing was absolutely wonderful. The surgeon, he won't win any prizes for his social skills, but he's a marvellous surgeon and only one percent of his patients ever get lymphodema. Everything was taken away, I have nothing in the nether regions now. My surgeon was first class, the nursing care was first class but the anaesthetist I'm not too sure about. I had a reaction to morphine because they probably gave me too much and I stopped breathing and I was in intensive care and that was pretty awful. I recovered from that but getting over the cancer was pretty hard. It was hard physically.

God, that first night after the op I'd come back from ICU I had the most marvellous nurse on and what we did – we worked it out together. I couldn't even take paracetamol at that point so she would come every hour and move me around and put a wet cloth on me and straighten my sheet so that I could sort of cope with the pain. That's really good care. A country lass, you know? I was allowed to go onto paracetamol pretty quickly because that's all I could tolerate. That's pretty hard when you've had major surgery.

I got a bit of a staph infection in the wound and they had to come in every day to dress it. It was a very hard time and it was an awful experience in terms of physical pain. It's a real process. It takes such a long time to recover from cancer of the uterus. But I've come good and I'm as healthy as a trout.

Rural women: additional challenges

Women who live in regional, rural and remote areas are faced with the additional challenge of leaving their home and familiar environment to access surgical care, while managing transport and accommodation in a crowded, fast-moving and alienating city environment. Travel distances included up to 200 km by road to an airport and up to 3,000 kilometres by air to a city. Consultations prior to surgery and chemotherapy and radiotherapy after surgery were available in regional centres, but those may also be hundreds of kilometres away from home and require repeat visits.

A woman from a remote area declined post-operative chemotherapy in the distant city where she had had surgery because she just wanted to go home. She had no effective analgesia, had extensive nerve damage to her bladder from the hysterectomy and had lost the ability to urinate. She was discharged with a post-operative infection that required surgical drainage and an in-dwelling catheter, and had to be taught to catheterise herself when she got home. She had no support person for the 3,000 km plane trip, but said she would have “crawled over the tarmac” to catch the plane rather than stay in the city.

Another rural woman had a traumatic post-operative course. She stayed with her son in the city for a couple of days post-operatively. Her stitches broke and she had to wait for 12 hours on a trolley at a nearby hospital to be re-admitted to theatre to repair the wound. She contracted golden staph, developed septicaemia, and spent six weeks in a city hospital, including a week in rehabilitation to learn to walk again. She then caught the train home on her own with her wound still open. There was no care provided for her when she arrived home and no review appointment. She had rung the local hospital for help and was told they did not provide care for people on the other side of the State border. No-one suggested she contact her GP so she did not do so. Her memory has been affected, and she is now fearful of surgery and putting off a hernia repair.

U2's story

U2 was married with two children, aged 21 and 24, living at home. Aged 48 when cancer diagnosed, 49 at time of interview. Surgery for ovarian cancer in an urban private hospital, in remission at interview.

It started they think, from the lining of my tummy. I had all the lining of my tummy taken off, which meant I had to have my spleen and my pancreas basically scraped. It went down into my ovaries. So they're putting it down as ovarian cancer because they're not really sure exactly where it started. Then it went onto the outside of my bowel. So I had about two-thirds of my large intestine removed.

I had massive amounts of pain – for years, every four weeks I've had a sharp pain and the doctor and gynos and naturopaths would put it down to irritable bowel. I went to (doctor) and we had X-rays done and I was absolutely bent over in pain and he referred me to a gynaecologist. At 9 o'clock that night I got a phone call from (gynaecologist) and he said to me ‘you've got cancer and it doesn't look good. We've got to get you into hospital straight away’.

So I had the operation and woke up cut to shreds. I had a drip on this side, a hole there, cut from here right down to the vagina bone and then an illiostomy bag over here and drips here.

After the operation, in intensive care (ICU), one of the nurses was not trained on replenishing the epidural and like you're laying there 5 hours after you've had this operation and you've had your stomach completely cut open and she's standing there trying to get it to go. Ten minutes later, no pain relief. A male nurse came in and I grabbed his hand and I said ‘Don't you leave me here. Don't you go. Stay with me’ because I didn't trust her. In the end they got a doctor to come in, he turned me over and you just bear it. But by the time it started working the pain had got up to the highest level that you could imagine. It was very traumatic.

I was in hospital for ten days and needed quite a few blood transfusions. They didn't let me have any rest at all. I was out of hospital and then, wham, I had the full bit (chemotherapy). I couldn't praise the hospital more highly. The nurses were great. Just don't let ICU happen again.

Discussion

This study found that the referral pathways to treat gynaecological cancer were efficient and effective; the women were diagnosed and referred for definitive management through well-established systems. They appreciated the quality of treatment, the efficiency and the care they received during the inpatient and acute phases of their care. However, we identified three main problems – the experience of post-operative morbidity that caused additional pain and suffering, the lack of coordination between the surgical team and general practitioners, and poor pain management. These did not appear linked to the type of cancer, but rather to the radical surgery experienced by almost all the women. Moreover, the concentration of surgery in tertiary hospitals meant women had to travel to receive care, which in some instances resulted in a disconnect between the surgical team and the local medical system.

An unanticipated finding was the high proportion of women who experienced post-operative complications, beyond those normally associated with recovery from surgery. Some of these were life-threatening and many were poorly managed, or there was such a delay in management that they caused considerable trauma. Discrepancies in pain management were also identified, and must be addressed.

Cancer treatment can be traumatic, with lasting adverse effects,Citation15,16 despite excellent clinical care and the outcome of lengthened life.Citation22 The worst period identified by the women in this study was the immediate post-operative weeks, when they were at their weakest and most vulnerable. Women with no one at home to nurse them and rural women were particularly at risk. Some women felt abandoned and unable to obtain medical care following discharge from hospital. Only when they made contact with their general practitioner, chemotherapy or radiotherapy team, and attended their post-operative check-up with the gynaecological oncologist, did care appear to be re-established.

The lack of effective linkages between the acute and primary sectors of the health system has been identified as a significant problem for many groups of patients and conditions. Communication between specialists and hospitals, on the one hand, and general practitioners on the other has been the subject of hospital-based reform since the mid-1990s.Citation22,23 The fact that it also emerged in this study was not unexpected, and was particularly problematic when the women lived far from the hospitals where they received treatment. Nevertheless the strength and volume of commentary on this problem, mentioned by almost all the women, was striking, and underlines its importance. Clearly, far more careful attention is needed in discharge planning and communication to arrange the handover of women from the surgical team to their gynaecologist or general practitioner, or both.

Although we interviewed a small number of women, and make no claim of generalisability, distinct patterns emerged from the interviews which make us confident that these experiences were a valid portrayal of what can go right and wrong in the clinical management of gynaecological cancer. This study focused on women who were undergoing follow-up treatment. We did not interview women who were ill or in hospital, who may have had different perspectives. There is also a survivor bias. Nevertheless, we learned about a range of experiences of both rural and urban women in a wide variety of treatment centres in four states of Australia, which gives our findings value and validity.

Recommendations

Discharge of all women to a general practitioner who is involved as part of the treatment team is critical. Every woman leaving hospital must be given a 24-hour contact number and an appointment with her referring doctor within 24 hours of discharge. Attention to effective pain management for all stages of diagnosis and treatment would also improve women's experience of care. Establishing reliable, consistent links between the surgical team and primary care in the immediate post-operative period is the most important challenge to the improvement of health system effectiveness for women with gynaecological cancer in Australia.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the women and their partners who told us their stories. This paper is based on a broader research study into the gynaecological workforce in Australia, funded by Cancer Australia. The full research team for that study included Prof Bill Martin, Dr Arthur Van Deth, Dr Josh Healy, Ms Llainey Smith and Ms Lulu Sun, in addition to the authors. The full report is entitled Review of the Gynaecological Cancers Workforce, 2008, conducted at the National Institute of Labour Studies, Flinders University, South Australia, Australia.

References

- M Berer. Reproductive cancers: high burden of disease, low level of priority. Reproductive Health Matters. 16(32): 2008; 4–8.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics population clock. http://www.abs.gov.au.

- Australian Health Priority Action Council. The National Service Improvement Framework for Cancer. 2005; Department of Health and Ageing: Canberra.

- Victorian Government Department of Human Services. Victoria's Cancer Action Plan. Melbourne; 2008. At: http://docs.health.vic.gov.au/docs/doc/Victorias-Cancer-Action-Plan-2008-2011-complete-document-Dec-2008

- Western Australia Department of Health. WA Health Cancer Services Framework. Perth; 2005. www.healthnetworks.health.wa.gov.au/cancer/docs/2797%20CancerFramework20800.pdf

- Cancer Council South Australia. Cancer control plan 2006–2009. 2006; Government of South Australia, Department of Health: Adelaide.

- Cancer Institute of New South Wales. New South Wales Cancer control plan 2007–2012: accelerating the control of cancer. 2006; Sydney.

- Queensland Government. Queensland Cancer Strategic Directions 2005–2010, Brisbane. www.health.qld.gov.au/cancercontrol

- Senate Community Affairs Committee. Breaking the Silence: A National Voice for Gynaecological Cancer. 2006; Canberra.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cancer in Australia: an overview. Sydney; 2010. www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=6442468003

- Cancer Council Australia. www.cancer.org.au/aboutcancer.htm.

- E Willis, J Dwyer, K Owada. Indigenous women's expectations of clinical care during treatment for a gynaecological cancer: rural and remote differences in expectations. Australian Health Review. 35: 2011; 99–103.

- Cancer survival and prevalence in Australia: period estimates from 1982 to 2010. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cancer Series No.69. Canberra; 2012.

- Merck Manual for Health Care Professionals. Principles of Cancer Therapy. www.merckmanuals.com/professional/hematology_and_oncology/principles_of_cancer_therapy/modalities_of_cancer_therapy.html#v978387

- MR Hampton, I Frombach. Women's experience of traumatic stress in cancer treatment. Health Care for Women International. 21(1): 2000; 67–76.

- K Booth, K Beaver, H Kitchener. Women's experiences of information, psychological distress and worry after treatment for gynaecological cancer. Patient Education and Counseling. 56: 2005; 225–232.

- D King, B Martin, J Dwyer. Review of the Gynaecological Workforce. 2008; National Institute of Labour Studies, Flinders University: Adelaide.

- Mapping Rural and Regional Oncology Services in Australia. Clinical Oncological Society of Australia; 2006.

- Minichiello, Aroni & Hays In-Depth Interviewing. Pearson Education Australia; 2008.

- Qualitative Solutions and Research. NVivo qualitative data analysis software. QSR International Pty Ltd. 2008; Doncaster.

- A Strauss, J Corbin. Grounded theory methodology: an overview. N Denzin, Y Lincoln. Handbook of Qualitative Research. 1994; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks CA.

- E Willis. Purgatorial time in hospitals. 2009; Lambert Academic Publishing: Germany.

- K Gimmer, G Hedges, J Moss. Staff perceptions of discharge planning: a challenge to quality improvement. Australian Health Review. 22(3): 1999; 95–109.