Abstract

Obstetric fistula is a complication of pregnancy that affects women following prolonged obstructed labour. Although there have been achievements in the surgical treatment of obstetric fistula, the long-term emotional, psychological, social and economic experiences of women after surgical repair have received less attention. This paper documents the challenges faced by women following corrective surgery and discusses their needs within the broader context of women's health. We interviewed a small sample of women in West Pokot, Kenya, during a two-month period in 2010, including eight in-depth interviews with fistula survivors and two focus group discussions, one each with fistula survivors and community members. The women reported continuing problems following corrective surgery, including separation and divorce, infertility, stigma, isolation, shame, reduced sense of worth, psychological trauma, misperceptions of others, and unemployment. Programmes focusing on the needs of the women should address their social, economic and psychological needs, and include their husbands, families and the community at large as key actors. Nonetheless, a weak health system, poor infrastructure, lack of focus, few resources and weak political emphasis on women's reproductive health do not currently offer enough support for an already disempowered group.

Résumé

La fistule obstétricale est une complication de la grossesse qui touche les femmes après un travail prolongé ou obstrué. Si le traitement chirurgical de la fistule a fait des progrès, les expériences émotionnelles, psychologiques, sociales et économiques à long terme des femmes après l'intervention réparatrice ont reçu moins d'attention. L'article documente les difficultés des femmes après l'opération et discute de leurs besoins dans le contexte plus large de la santé féminine. Nous avons interrogé un petit échantillon de femmes à West Pokot, Kenya, pendant deux mois en 2010, avec huit entretiens approfondis avec des patientes présentant une fistule et deux discussions de groupe, chacune avec des femmes ayant une fistule et des membres de la communauté. Les femmes ont déclaré que leurs problèmes se sont poursuivis après l'intervention réparatrice : séparation, divorce, infécondité, stigmatisation, isolement, honte, diminution du sentiment de valeur personnelle, traumatisme psychologique, conceptions erronées des autres et chômage. Les programmes axés sur les besoins des femmes doivent aborder leurs besoins sociaux, économiques et psychologiques et associer les conjoints, les familles et l'ensemble de la communauté comme acteurs clés. Néanmoins, la faiblesse du système de santé, la médiocrité des infrastructures, le manque d'attention, l'insuffisance des ressources et la faible priorité politique accordée à la santé génésique des femmes ne permettent pas de soutenir suffisamment un groupe déjà démuni.

Resumen

La fistula obstétrica es una complicación del embarazo que afecta a las mujeres tras un parto obstruido prolongado. Aunque se han visto logros en el tratamiento quirúrgico de la fístula obstétrica, las experiencias emocionales, psicológicas, sociales y económicas de las mujeres a largo plazo después de la reparación quirúrgica han recibido menos atención. En este artículo se documentan los retos que enfrentan las mujeres después de una cirugía correctiva y se discuten sus necesidades en el contexto más amplio de la salud de las mujeres. Entrevistamos a una pequeña muestra de mujeres en West Pokot, Kenia, durante un plazo de dos meses en 2010: ocho entrevistas a profundidad con sobrevivientes de fístula y dos discusiones en grupos focales, una con sobrevivientes de fístula y la otra con integrantes de la comunidad. Las mujeres informaron problemas continuos después de la cirugía correctiva, tales como separación y divorcio, infertilidad, estigma, aislamiento, vergüenza, disminuida autoestima, trauma psicológico, percepciones erróneas de otras personas y desempleo. Los programas centrados en las necesidades de las mujeres deben atender las necesidades sociales, económicas y psicológicas de cada mujer e incluir a su esposo, familia y comunidad como actores clave. Sin embargo, debido a las deficiencias del sistema de salud y la infraestructura, falta de enfoque, pocos recursos y poco énfasis político en la salud reproductiva de las mujeres, no se ofrece suficiente apoyo a un grupo de por sí desempoderado.

“It was painful. It was bad. When I felt the urge to pass urine it would just flow without stopping. If you stand up it pours. There was no stopping it, no break. Some were bad to me, some treated me with pity. They looked down upon me. They said I am spoilt, they said I was spoiling the ward. At first it was the nurse who insulted me. She said: ‘For how long are you going to stay here? You know you have really spoilt this ward!’ She said it every day. Others treated me kindly saying: ‘Just bear it for now, you will get well’. They pitied me.” (Chepkiror, aged 24, divorced)

According to a needs assessment conducted in 2004 in Mwingi, Kwale, Homabay and West Pokot Districts of Kenya, women living with obstetric fistula face stigma and isolation.Citation10 As a result, their access to resources and participation in economic activities is curtailed. In addition, their isolation discourages them from accessing health care and hinders their utilization of health services.

This paper focuses on the challenges faced by obstetric fistula survivors after corrective surgery in West Pokot, a rural district in northwest Kenya with an estimated prevalence of fistula of one per 1,000 women aged 11–50 years.5

Methodology

West Pokot is a semi-arid area with rough terrain on the slopes of the Cherangani hills and Mt Elgon. The district is mainly inhabited by the Pokot people, a nilotic tribe who depend on nomadic pastoralism for their livelihood. Over time, a few have settled down to agriculture, but the majority of the community are widely dispersed, often following water and pasture for their animals. A large expanse of the district is deprived of any motorized transport save for a tarmac road that crosses the southern edge.

The area is served by one government district hospital, a sub-district hospital, a mission hospital and three health centres, which are few given the size and population of the district. In addition, there are 27 dispensaries spread across the district. A majority of the inhabitants rely on healers during illness and traditional birth attendants for delivery. The Pokot practice type III female genital mutilation (FGM) and marry off their girls at puberty. The two practices are linked to adverse reproductive health events,Citation11,12 and contribute to morbidity following labour. Sentinelles, a non-governmental organization, assists women and girls to escape FGM and forced marriages. They also assist women with obstetric fistula and sponsor fistula surgery at Ortum Mission Hospital. Visiting surgeons from the African Medical and Research Foundation and Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital conduct repair surgery, with Sentinelles making follow-up home visits after discharge from hospital. This was an ideal entry point for our study.

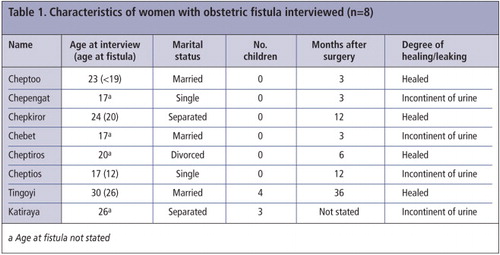

The study was carried out over a two-month period in 2010. Four women were interviewed during home visits, three when they visited Sentinelles for further help, and another at the Sentinelles rescue centre, where she was living. The eight women were aged 17–30 years, and had undergone corrective surgery for obstetric fistula at least once. The interviews at home also allowed observation of the women's daily lives. The interviews took place 1–4 years after the fistula had occurred and 3–36 months after the most recent surgery. Information about their lived experience with obstetric fistula and the factors that influenced their reintegration after surgery was sought, particularly their experience of living with stigma. Two focus group discussions (FGDs) were also held, the first with seven obstetric fistula survivors and a second with 12 men and women who were participants in a community FGM awareness seminar. These discussions sought to establish community perceptions of and support to women who had suffered obstetric fistula.

The interviews and focus group discussions were taped, transcribed and translated from Pokot to English. Note taking was also used in case of technical failure. Thematic analysis based on grounded theory was used to process the data.Citation13 Kenyatta National Hospital/University of Nairobi Ethics Research Committee approved the study and research permission was granted by the Government. Participants gave verbal consent and were informed of their right to withdraw at any stage of the study. Those who required further support were enrolled with Sentinelles.

This was an exploratory study with a small number of participants. While the women's experiences cannot be generalised, the findings offer important insights for the design of re-integration programmes. All the women's names in the text are pseudonyms.

Findings

Of the eight women interviewed, all had undergone FGM. Two had never been married, two were married, another was married but living separately in the same compound with her husband, and three were divorced. Those who were single or divorced were living with their parents, except one who had been forced out of her natal home. All the married women had experienced periods of separation from their husbands, both while they had the fistula and after corrective surgery. The women had low literacy levels with formal education attained ranging from primary class three to class five. One woman was pursuing vocational training at a local polytechnic. The women's surgery had been sponsored and paid for by Sentinelles.

Six of the eight women had experienced the fistula during their first delivery. Seven reported prolonged obstructed labour leading to stillbirth; the eighth woman had had a precipitate labour and her baby had survived. All the women had been assisted by an unskilled birth attendant during the labour that caused the fistula except for one that had occurred in hospital. Four of the women had completely healed, while four others were awaiting further corrective surgery (Table 1). All the women had undergone more than one corrective surgery.

The problems the women faced fell into three main categories: stigma and psychological trauma, marital instability (divorce, separation and infertility) and economic difficulties.

Stigma and psychological trauma

Stigma, which manifested itself variously from subtle to blatant discrimination and isolation, continued even after corrective surgery. Stigma was directed at the women both by their families and the community, who isolated them and did not allow them to participate fully in household chores or social activities. They were subjected to negative comments about their previous condition, labelled as spoiled and not accepted.

One woman, although she was invited to social events like weddings and rites of passage, was not allowed to help with the cooking or serving the guests despite the fact that she had healed and was physically able to help. She described it thus:

“But you see, you can't touch people's food. The [guests] will say what is that they have put in the food? These hands have passed many different problems!” (Tingoyi, age 30, married, four children)

“People my age believe that I am useless [because] I had a fistula.” (Chepengat, age 17, never married)

“I had no problems from my husband; I am the one who had fears of the unknown – that I might smell of urine again. Was I like everyone else?... I didn't see anything wrong initially but now, after the second surgery, I don't know what to expect.” (Cheptoo, age 23, married, no children)

The experience of stigma for all eight women led to long-term psychological trauma. Long after corrective surgery, the women were still living with memories of fistula and made every effort to block out any linkage to fistula. For instance, one survivor denied absolutely ever having been operated on, yet records showed otherwise. Others, upon recalling their experience of obstetric fistula, broke down and cried. For them, the emotional scars seemed so fresh in their minds, and they reported feeling pain just thinking of the past.

“I was only told to abstain for six months from sexual activity. But what is bitter [is that] I stayed for four years without sex and I was too afraid to be with a man. I was badly affected psychologically and when I remember, my head wants to burst and my blood pressure gets high.” (Cheptoo, age 23, married, no children)

Effects on marriage and marriage prospects

Obstetric fistula survivors are often separated from their husbands after surgical repair, even though the repairs are successful. The survivors' marriages are jeopardised twofold: first, because they have to abstain from sex for six months to allow healing and two years before conceiving, and, second, because the husbands take the condition as a bad omen for the marriage and often abandon their wives and move to live with another wife or wives. This was reported in the interviews with the eight women as well as by the focus group discussion with fistula survivors. Separation left the survivors without any social or material support.

“I had the operation but he wasn't there at all. I also lost the baby. Later, he insulted me. He said: ‘You wanted to give birth. I will leave you here.’ That pained my heart. I got demoralized and went to my mother's home after the [second corrective] surgery. After the first [corrective] surgery I had gone to my husband's house. But they didn't care for me as a sick person.” (Chepkiror, aged 24, divorced)

“I had no one to help me, no one near me… That was the biggest problem… how could I fend for myself? I thought [my husband] would be there for me. I didn't think he would stay away from me! But when I told him we had to abstain [from sex] he abandoned me. When I was advised on how to win him back, he [returned]. He asked me, have you been told it is allowed for us to ‘meet’? I said yes. The six months are over, so we can. So he came back.” (Tingoyi, aged 30, married, four children)

“The biggest [challenge] in life? Not being able to progress well in life. I mean I got married, but I didn't get a good life. My life went kombokombo (bad).” (Chepkiror, aged 24, divorced)

The difficulties the women faced while trying to cope with post-operative instructions were daunting. Often the husband did not understand why, when the wife no longer leaked urine, she had to abstain from sex for six months. For their part, the women feared engaging in sexual intercourse before that time, so they would go to their parents' home until they healed. This separation affected their marriages as well as their re-integration into the community.

In a community where a woman's worth is gauged by her ability to fetch many cows as a bride price for her family and clan, and her ability to give birth, the women often found themselves to be of little value to both families even after surgery. The community's perception of obstetric fistula survivors gave them little chance of leading a normal married life. If they had unsuccessful surgery, they perceived their chances of marrying as being completely gone.

“It is not easy for me to get married. They [community] believe you won't deliver again, and you are smelling of urine… Bride price will not be discussed – I am now valueless.” (Chepengat, age 17, never married, unsuccessful repair)

“I am worried whether I will get a baby afterwards now that I lost this one. I will be unhappy if I don't get another baby” (Chepengat, age 17, never married, unsuccessful repair)

Economic challenges

Gender inequality exists in Pokot, a patriarchal society where resources are controlled by men. The lack of economic empowerment was a big challenge after surgery as the women found themselves dependent on their spouses and other relatives. Often, they were not able to participate in economic activities as they used to, either because of lack of capital or physical strength or the negative label the community attached to them. They were unable to undertake heavy manual work and prospective employers were reluctant to hire them as domestic servants or in hotels, while in other cases customers shied away from businesses the survivors owned or worked for. As a result, they often found themselves without any means to generate income and were disconnected from social forms of fundraising like harambee – a form of community-directed social insurance. Consequently, they needed help to meet their daily needs.

Consequences of unsuccessful repair

Three of the eight women interviewed had unsuccessful repairs and were awaiting further surgery. Unsuccessful repairs left survivors worse off; they were seen to be cursed and were alienated.

“Until now, the operation hasn't assisted me as I am still leaking urine. It is still a challenge. The societal perception about my foul smell is distressing. They think I am cursed and am not supposed to get near people.” (Chepengat, age 17, never married, unsuccessful repair)

Discussion

Obstetric fistula has been shown to have negative social implications for women in sub-Saharan Africa, causing moderate to severe disruption in marital, family and community relationships, affecting ability to work and religious observance practices.Citation14 In Kenya most of these findings have been documented in health care facility-based studies, focusing on the period before women have surgery.Citation5,10 Our study examined survivors' lived experiences 3–36 months following surgery.

The women living with obstetric fistula in West Pokot reported serious problems following corrective surgery, including loss of relationships, infertility, stigma, being labelled as spoiled, isolation, shame, misperceptions about fistula, reduced sense of worth, psychological trauma, and economic loss. These challenges have also been reported in studies of the pre-surgery period.Citation6,10,11,15,16

Other studies, including a study by EngenderHealth and the Women's Dignity Project in Tanzania, also found that obstetric fistula survivors experience stigma after surgery.Citation17 In Tanzania, fistula survivors, fearing negative comments, would not tell other people about their surgery, to avoid these problems. Other recent studies also attest to isolation after surgery.Citation18

The stigmatisation of fistula survivors is embedded in the cultural beliefs of the Pokot community concerning childbirth. In West Pokot, obstetric fistula survivors are labelled as having an illness that leaves them socially polluted. Thus, they are seen as unclean and undeserving to participate in roles associated with women in the community, such as cooking and milking cows. They are not fully accepted back by their community after surgery even though they may be healed and no longer leaking urine or faeces. They are permitted into social circles only partially and cautiously. The illness leaves a permanent stigmatising label on the survivors. This stigma is anchored in various cultural beliefs. The concept of pollution resulting from body flows, like menstruation, is not confined to the Pokot. GreenCitation20 has documented these concepts in many other African cultures.

The stigma as manifested in our study is consistent with Goffman'sCitation19 description of stigma, the situation of the individual who is disqualified from full social acceptance in several ways. Goffman argues that individuals are constantly alive to what others see as their failings, arousing feelings of deficiency. Shame arises from the individual's perception of her own deficient attributes. In this study, survivors' reduced sense of worth arose from having heard so many times from the community that they had lost their value as women. Their awareness of the community's negative perception of their condition caused further self-doubt, even when they were accepted back by their families. The self-isolation that ensued was a sign of uneasiness about and an avoidance of anticipated unpleasant social interactions.

In our study, the survivors were treated as people “with a blemished record”. While it is important to understand that stigma and reduced sense of social worth originate from the beliefs of the community about obstetric fistula, it is also imperative to recognise how this perception influences how the community views survivors after surgery.

Although the various components of stigma, as conceptualised by Link and PhelanCitation21 – labelling, stereotyping, separation, status loss and discrimination – appeared intertwined in most of the survivors' accounts, they also occurred singly in some cases. Other internal processes, namely reduced sense of self-worth, low self-esteem, overwhelming helplessness and self-isolation interacted with enacted stigma to further contribute to felt stigma by the survivors.

Yeakey et alCitation22 have described poor mental health amongst fistula survivors in Malawi. In Kenya, women attending obstetric fistula surgical treatment at the Kenyatta National Hospital were found to be predisposed to high levels of depression.Citation23 In a meta-analysis of literature on obstetric fistula, Holtz and AhmedCitation16 established that surgical treatment usually closes the fistula and improves the physical and mental health of affected women, but recommended additional social support and counselling for women to successfully reintegrate socially following fistula repair. Our study supports this view.

While primary data on divorce, abandonment and separation during the post-surgery period are scant, our findings confirm predictions in other studies that survivors may end up separated or divorced owing to their condition, while those who are not married may remain so.Citation16,17,24 A recent study in Malawi found that while a substantial number of women are divorced by their husbands following the occurrence of obstetric fistula, other fistula survivors remarried men who were fully aware of their condition.Citation22 Some men, however, chose to remain with their wives but also married other women with whom they could have sexual relations.

Determinants of divorce and separation after fistula vary across cultures. For instance, in Malawi divorce and separation were less likely after fistula if the couple had other surviving children, while in Kenya the women who did have children were often separated from their husband.Citation10 Pokot marital and kinship patterns allow for polygyny, hence some husbands choose to remain with their wives but marry another woman. This maintains the woman's safety nets despite her physical illness and reproductive disability. However, some women complained that their husbands neglected them materially after choosing such an arrangement. We did not find any survivor who had married a different partner after healing, although those who discussed this possibility pointed to reduced chances of such a happening in their community.

Infertility and ostracism by the community are phenomena that are yet to be documented elsewhere in the region. Fertility and future reproductive ability dominated the interviews in our study. In attempting to fulfill expected gender roles, the women were often frustrated when they could not conceive soon after corrective surgery, which escalated their feelings of unworthiness, self-derogation and shame.Citation25 Their fertility was doubted by society and themselves, a constant reminder of the past.

Finally, obstetric fistula survivors faced economic challenges irrespective of outcome of the surgery. Other studiesCitation1,3,16,24 have also pointed to the economic challenges that fistula survivors may face, and have called for intervention on the economic front as a vital component of reintegration. For instance, MohammadCitation26 describes a re-integration programme for fistula survivors in Nigeria, where the need for economic empowerment was given priority, to good effect. Nonetheless, in some studies, for example Pope, Bangser and Requejo,Citation27 women have been shown to be able to resume normal economic activities, with their families as the core supporting unit.

Recommendations

Following corrective surgery for fistula repair, stigma and other socio-economic problems may reverse gains and hopes of re-integrating into their relationships and community, built up during hospitalisation. Women with unsuccessful surgical repair face greater stigma and other challenges than those who are healed. Any programmes focusing on the re-integration needs of the women should also include husbands as key actors and the community at large, as they are the ones who find it difficult to accept the women back. From the perspective of women's reproductive health and rights, the combination of early marriage and pregnancy, which increase the risk of obstructed labour, should also be challenged.

We recommend that public health education and re-integration programmes should target broader outcomes beyond corrective surgery. The women require holistic support, bringing together the family, community and health care providers so as to address their social, economic and psychological needs. Nonetheless, a weak health system, poor infrastructure, lack of focus, few resources and weak political emphasis on women's reproductive health do not currently offer enough support for an already disempowered group. Thus, the government should lead with programmes to ensure overall improved women's health.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support of the Institute of Anthropology, Gender and African Studies, University of Nairobi. We thank the Sentinelles team in West Pokot, Kenya, for linking us with study participants, and to the study participants who bravely and generously shared their stories.

References

- UN Population Fund. The campaign to end fistula. Annual Report. 2005; UNFPA: New York.

- F Donnay, K Ramsey. Eliminating obstetric fistula: progress in partnership. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 94: 2006; 254–261.

- World Health Organization. Make every mother and child count: World Health Report. 2005; WHO: Geneva.

- C Vangeenderhuysen, A Prual, D Ould el Joud. Obstetric fistula: incidence estimates for sub-Saharan Africa. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 73: 2001; 65–66.

- H Mabeya. Obstetric fistula: characteristics of women with obstetric fistula in the rural hospitals in West Pokot, Kenya. WHO/GFMER/IAMANEH. 2004; WHO: Geneva.

- RJ Cook, BM Dickens, S Syed. Obstetric fistula: the challenge to human rights. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 87: 2004; 72–77.

- ML Sagna, N Hoque, T Sunil. Are some women more at risk of obstetric fistula in Uganda? Evidence from the Uganda Demographic and Health Survey. Journal of Public Health in Africa. 2: 2011; e26.

- PM Tebeu, L de Bernis, AS Doh. Risk factors for obstetric fistula in the Far North Province of Cameroon. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 107(1): 2009; 12–15.

- AMREF. Summary assessment report: Capacity needs assessment for strengthening health systems to increase utilization of safe motherhood and obstetric fistula services in Kenya. 2007; AMREF: Nairobi.

- Ministry of Health Kenya UNFPA. Needs assessment of obstetric fistula in Kenya: final report. 2004; MOH: Nairobi.

- WHO. Female genital mutilation and obstetric outcome: WHO collaborative prospective study in six African countries. Lancet. 367: 2006; 1835–1841.

- AM Khisa, IK Nyamongo. What factors contribute to obstetric fistulae formation in rural Kenya?. African Journal of Midwifery and Women's Health. 5(2): 2011; 95–100.

- A Strauss, J Corbin. Basics of qualitative research: grounded theory procedures and techniques. 1990; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA.

- KM Roush. Social Implications of obstetric fistula: an integrative review. Journal of Midwifery and Women's Health. 54: 2009; 21–33.

- International Federation of Obstetricians & Gynecologists. Ethical guidelines on obstetric fistula. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 94: 2006; 174–175.

- A Holtz, S Ahmed. Social and economic consequences of obstetric fistula: lLife changed forever?. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 99: 2007; S10–S15.

- EngenderHealth Women's Dignity Project. Risk and resilience: obstetric fistula in Tanzania. 2006. www.engenderhealth.org/pubs/maternal/risk-resilience-fistula.php

- Family Care International UN Population Fund. Living testimony: obstetric fistula and inequities in maternal health. 2007; FCI, UNFPA: New York.

- E Goffman. Stigma: notes on the management of spoilt identity. 1963; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs NJ.

- EC Green. Indigenous Theories of Contagious Disease. 1999; Altamira Press: Walnut Creek, CA.

- B Link, J Phelan. Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology. 27(1): 2001; 363–385.

- MP Yeakey, E Chipeta, F Taulo, AO Tsui. The lived experience of Malawian women with obstetric fistula. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 11(5): 2009; 499–513.

- K Weston, S Mutiso, JW Mwangi. Depression among women with obstetric fistula in Kenya. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 115(1): 2011; 31–33.

- A Mwangi, C Warren. Obstetric fistula: can community midwives make a difference? Findings from four districts in Kenya. 2008; UNFPA, Population Council: Nairobi.

- LT Mselle, KM Moland, B Evjen-Olsen. “I am nothing”: experiences of loss among women suffering from severe birth injuries in Tanzania. BMC Women's Health. 11: 2011; 49.

- RH Mohammad. A community program for women's health and development: implications for the long-term care of women with fistulas. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 99: 2007; 138–142.

- R Pope, M Bangser, JH Requejo. Restoring dignity: social reintegration after obstetric fistula repair in Ukerewe, Tanzania. Global Public Health. 6(8): 2011; 859–873.