Abstract

Recent studies on development aid from European donors revealed that their funding of the health sector in sub-Saharan Africa rarely includes performance measures suitable for tracking operational progress in improving sexual and reproductive health and rights. Analysis of health sector agreements verifies this. Particularly lacking are metrics related to four critically important areas: 1) reducing mortality and morbidity from unsafe abortion, 2) preventing and treating gender-based violence, 3) reducing unwanted pregnancies among the poorest women, and 4) reducing unwanted pregnancies among adolescents. During 2011 and the first half of 2012, the authors interviewed 85 experts in health service delivery, ministries of health, human rights, development economics and social science from sub-Saharan Africa, Europe and the United States. We asked them to identify measures to assess progress in these areas, and built on their responses to propose up to four practical performance measures for each of the areas, for inclusion in health sector support agreements. These measures are meant to supplement, not replace, current population-based measures such as changes in maternal mortality ratios. The feasibility of using these performance measures requires political commitment from donors and governments, investment in baseline data, and expanding the role of sexual and reproductive health and rights civil society in determining priorities.

Résumé

De récentes études sur l'aide au développement des donateurs européens ont révélé que leur financement du secteur de la santé en Afrique subsaharienne inclut rarement des mesures des performances permettant de surveiller les progrès opérationnels accomplis dans l'amélioration de la santé et des droits génésiques. Les accords du secteur de la santé le confirment. Des mesures font particulièrement défaut dans quatre domaines majeurs : 1) baisse de la mortalité et de la morbidité dues aux avortements à risque ; 2) prévention et traitement de la violence sexiste ; 3) réduction des grossesses non désirées chez les femmes pauvres ; et 4) réduction des grossesses non désirées chez les adolescentes. En 2011 et au premier semestre 2012, les auteurs ont interrogé 85 experts en prestation de services de santé, ministères de la santé, droits de l'homme, économie du développement et sciences sociales d'Afrique subsaharienne, d'Europe et des États-Unis. Ils leur ont demandé d'identifier des mesures pour évaluer les progrès dans ces domaines et de se fonder sur leurs réponses pour proposer quatre mesures pratiques des performances pour chaque domaine, en vue de leur inclusion dans les accords de soutien du secteur de la santé. Ces indicateurs devraient compléter, et non remplacer, les mesures actuelles à base démographique telles que les changements des taux de mortalité maternelle. L'utilisation de ces mesures des performances exige une volonté politique des donateurs et des gouvernements, des investissements dans les données de référence et un élargissement du rôle que joue la société civile dans la détermination des priorités relatives à la santé et aux droits génésiques.

Resumen

Recientes estudios sobre la ayuda financiera de donantes europeos para el desarrollo revelaron que su financiación del sector salud en Ãfrica subsahariana rara vez incluye medidas de desempeño adecuadas para seguir los progresos operativos en mejorar la salud y los derechos sexuales y reproductivos. Los acuerdos del sector salud lo verifican. En particular, hacen falta métricas relacionadas con cuatro áreas de importancia fundamental: 1) disminuir las tasas de mortalidad y morbilidad maternas atribuibles al aborto inseguro, 2) impedir y tratar la violencia de género, 3) disminuir el índice de embarazos no deseados entre las mujeres más pobres y 4) disminuir el índice de embarazos no deseados entre las adolescentes. Durante el 2011 y la primera mitad del 2012, los autores entrevistaron a 85 expertos en la prestación de servicios de salud, ministerios de salud, derechos humanos, economía del desarrollo y ciencias sociales, provenientes de Ãfrica subsahariana, Europa y Estados Unidos. Les pedimos que identificaran medidas para evaluar los avances en estas áreas y que se basaran en sus respuestas para proponer hasta cuatro medidas prácticas del desempeño para cada área, para inclusión en los acuerdos de apoyo al sector salud. El objetivo de estas medidas es suplementar, no sustituir, las medidas actuales basadas en la población, tales como cambios en la razón de mortalidad materna. La viabilidad de utilizar estas medidas del desempeño requiere compromiso político de los donantes y gobiernos, inversión en datos de base y ampliación del rol de la sociedad civil en determinar prioridades en salud y derechos sexuales y reproductivos.

The development field has, with varying levels of success, attempted to measure its impact, starting in earnest with the logical framework which the US Agency for International Development introduced in 1970 as a way of reporting the effectiveness of development aid to the US Congress.Citation1 For the field of sexual and reproductive health and rights, demonstrating results from specific interventions has proven particularly difficult. There are many reasons for this, including the difficulty of isolating the effects of socio-cultural factors on practical interventions to improve outcomes.

Despite these difficulties, donor agencies are now placing even greater emphasis on documenting how well resources are being used and whether results are being achieved. They say they need to respond to political and public doubts about aid in general and ensure that scarce development resources go to the most effective programmes. For example, the new business plan of the UK Department for International Development clearly states: “Results, transparency and accountability will be our watchwords and will guide everything we do.”Citation2 Germany also focused on increasing effectiveness in a recently-released development policy.Citation3 This emphasis on results is now similar for all major donors. The World Bank recently approved a program-for-results financing instrument that directly links disbursement of funds to the delivery of defined results by the countries concerned.Citation4

Recent studies carried out by us of the official development assistance (ODA) for health system strengthening of the major European donors (Denmark, Finland, Germany, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and United Kingdom) led us to recommend the development of better performance metrics for key elements of sexual and reproductive health and rights, focusing on sub-Saharan African country programmes.Citation5–7

The reproductive health field does not suffer from a lack of metrics. Indeed the 15-year review of the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) recommended 73 indicators for cross-country monitoring,Citation8 and the Maputo Plan of Action has over 100 indicators to monitor progress.Citation9 Guidance on what a reproductive health indicator should include also exists,Citation10 and WHO has established 17 indicators for global monitoring of reproductive health.Citation11 WHO has also recently identified 11 maternal, newborn and child health impact indicators to monitor goals achieved under the UNGASS, and recommended that they be disaggregated by equity.Citation12 Footnote* However, practical SRHR metrics that are useful to track progress in the implementation of health sector programmes for sub-Saharan Africa are scarce.

This paper presents the results of a review of SRHR metrics in African health sector strategies and of qualitative interviews with 85 experts to see if consensus could be reached about the top three or four most important SRHR measures for inclusion in health sector support agreements. While there was not complete agreement among the interviewees, we have synthesized their responses to capture the most common and strongly held views and discuss the recommended indicators.

Methodology

Our previous analysesCitation5 revealed that metrics to assess progress in health systems were particularly lacking in the areas of abortion-related mortality and morbidity, preventing and treating gender-based violence, helping the poorest women avoid unwanted/unplanned pregnancies, and reducing unwanted pregnancies among adolescents.

We reviewed published documents on performance metrics, including Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines and indicators, surveys by the World Bank, and UN Population Fund (UNFPA) publications, as well as health sector policies and plans from 29 African countries.Citation14

Our definition of “performance indicator” is consistent with that provided by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development: “a variable that allows the verification of changes due to the development intervention or shows results relative to what was planned”.Citation13 We have focused on this level of indicator because it is the missing link between output measures (e.g. numbers of health personnel trained) and long-term impact measures (e.g. changes in contraceptive prevalence rates).

We interviewed the following 85 metrics experts with a variety of relevant experience. These were open-ended interviews where we asked what indicators they would look for in health sector support agreements that would provide practical measures as to whether SRHR interventions in our four chosen areas were working or not.

| • | Ministry of Health officials in Ghana, Kenya, Senegal and Uganda, and public health, demographic and health systems experts from these countries (10); | ||||

| • | SRHR civil society organizations specializing in services to youth, protection of sexual minorities, gender-based violence, safe abortion, and family planning from Germany, Netherlands, Kenya, Uganda and UK, e.g. Rutgers WPF, DSW, Amref, Dance4Life, and Choice for Youth (30); | ||||

| • | Monitoring and evaluation staff of the International Planned Parenthood Federation, Marie Stopes International, EngenderHealth and Ipas, both at their US headquarters and in Africa (15); | ||||

| • | SRHR metrics experts in DFID as well as the Dutch and German development Ministries (5); | ||||

| • | European donor, UNFPA and World Bank staff in Kenya and Uganda (12); | ||||

| • | Rights groups Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch (3); and | ||||

| • | Development economists, academics, evaluation experts and general health systems specialists who work at varying levels of international development and global health (10). | ||||

Findings

Health sector support agreements

Countries' health sector policies and plans are important not only because they represent national health priorities but also because most European donors are committed to aligning their development assistance with national policies, preferably ones that integrate SRHR into national health systems. This commitment is shared largely by their sub-Saharan Africa partners and was also endorsed at the recent Family Planning Summit in July 2012. Some of the countries have separate reproductive health strategies, but we focused on the place of SRHR within health sector support programmes with a sector-wide approach since integration will ultimately lead to more sustainable services.

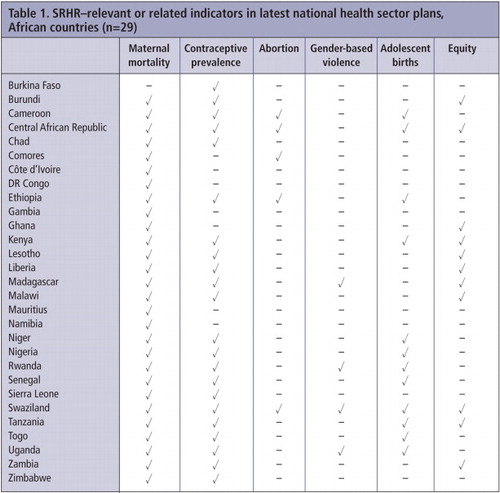

We examined whether these plans had indicators, targets and specified objectives pertaining to: maternal mortality (mostly maternal mortality ratio), contraceptive use (mostly contraceptive prevalence rate), abortion, gender-based violence, adolescent birth rate or related adolescent-specific indicators (including HIV prevalence in 15–24 year olds), and indicators pertaining to equity (mainly number of facilities and trained staff in rural or underserved areas but not specifically for SRHR). Table 1 presents findings from 29 African countries whose sector plans were available online in English or FrenchFootnote*.

The most commonly used SRHR metrics – changes in maternal mortality and contraceptive prevalence – are long-term indicators that are not amenable to tracking performance in a time-frame useful for making corrections to programme implementation. Performance metrics which support Health Ministries to monitor progress are lacking in most of the countries surveyed. In some cases, the health sector policies mentioned the issues but did not identify an indicator or target. We considered the presence of an indicator or target as essential on the assumption that more attention would be paid to interventions that are measured and reported on. Although some countries had more metrics than others, in-depth analysis would be needed to determine whether this reflects increased government commitment to SRHR or not. However, this review did confirm that indicators for our four key topics were rare – and particularly for abortion and gender-based violence – reinforcing the findings of our previous mapping studies.

Interviews with SRHR experts

The SRHR experts we interviewed shared a commitment to finding better ways to provide SRHR services to women and to develop methodological tools to understand what works, what doesn't and why. A cross-cutting theme throughout was that the process of selecting indicators to measure progress is by its very nature, reductionist. Metrics are summary measures that only give part of the picture; the challenge is selecting those metrics that are not only useful in and of themselves but can also offer insight into how SRHR access is progressing generally. In various ways, many of the experts raised the concern that the push towards measurement could stifle creativity or press donors and countries to focus on the wrong things.

The selection of measures encompasses political will of countries and donors, cultural factors and practical questions of measurement. A recent analysis of progress in achieving ICPD goals recommended that measuring the “enabling environment” was particularly important for SRHR.Citation15 We emphasized to the experts that we sought metrics that could be useful now while recognizing that much work needs to be done to develop ways of tracking the broader issues. We employed an iterative approach which involved repeat interviews with many of the respondents between September 2011 and June 2012. We prepared a working document with their initial recommendations and asked all of them to comment on these. The initial list changed as we received more input.

We then synthesized their responses to capture the most agreed upon and important recommendations. We insisted on limiting the recommendations to three or four to avoid the problems of a long list.

Recommended indicators

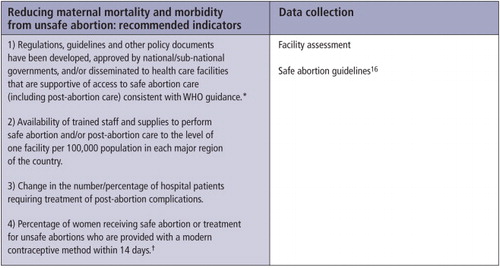

1. Reducing maternal mortality/morbidity from unsafe abortionFootnote*

WHO defines unsafe abortion as “a procedure for termination of an unintended/unwanted pregnancy done either by people lacking the necessary skills or in an environment that does not conform to minimum medical standards, or both”.Citation17 Unsafe abortions usually take place in clandestine circumstances, with poor hygiene and often administered by untrained and unsupervised individuals. As such, their consequences can be deadly – unsafe abortion contributes to a substantial proportion of maternal mortality, significant life-time infertility, and a wide array of morbidity among women who survive, including haemorrhage, infection, and poisoning.Citation18

Safe medical or surgical abortion carries very little risk. At ICPD, governments agreed on a definition of reproductive health that included abortion in circumstances where it is not against the law (Para. 8.25).Citation19 The same paragraph cites the critical public health impact of unsafe abortions. Many have argued that the MDGs will not be reached without access to safe abortion.Citation20 As medical abortion becomes more widely available and as the stigma surrounding the provision of services wanes, the experience of other regions suggests that the suffering of women in sub-Saharan Africa through unsafe procedures might soon be mitigated.

Safe abortion care (adapted from WHO)Citation16 includes: access to safe abortion; access to treatment for complications of abortion; WHO-recommended surgical and medical methods of uterine evacuation; contraceptive information, counselling and methods; and screening, treatment and referral for other sexual and reproductive health problems.

A general theme that emerged in all of the discussions was the importance of interpreting data in context. For example, an increase in the number of hospital patients seeking treatment due to unsafe abortion might mean that the procedures are getting more risky or that women are feeling safer about seeking treatment. Conversely, a decline in the number might, and hopefully would, indicate improvements in safety, but it might also indicate an increase in stigma or threats of prosecution.

All interviewees agreed that the most important goal is to ensure that women who choose to terminate a pregnancy are able to do so with both safety and dignity and that good quality family planning should also be easily available to help avoid future unwanted pregnancies. Indicator 4 was widely recommended by the experts. Studies in multiple regions have indicated high levels of contraceptive uptake among women who are offered a method following abortion care, even when national contraceptive prevalence is relatively low.Citation21

It has also been shown that providing contraception at the same location as providing safe abortion care increases the contraceptive uptake rate,Citation22 and that training abortion providers to monitor this indicator is key to success.Citation23 There was general recognition, however, that there is no perfect contraceptive and women have always experienced unwanted pregnancies. Thus, the need to help women have abortions in safety and dignity remains an important strategy to reduce maternal mortality and morbidity.

2. Preventing and treating gender-based violence

The United Nations General Assembly defines violence against women as “any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual, or psychological harm or suffering for women, including threats of such acts, coercion, or arbitrary deprivations of liberty, whether occurring in public or private life”.Citation24

Although the global incidence of violence is difficult to establish because of definitional variations and the sensitivity of reporting, it is consistently reported that as many as one in three women has been beaten, coerced into sex, or abused in some other way. Up to one quarter of women are abused during pregnancy.Citation25 A review of 50 population-based surveys on violence by intimate partners indicates that 10–50% of women who have ever had partners have been “hit or otherwise physically assaulted by an intimate male partner at some point in their lives”.Citation26 A recent multi-country study of violence showed similarly high but varying prevalence of violence: the proportion of ever-partnered women who had ever experienced physical or sexual violence (or both) ranged between 15%–71%.Citation27

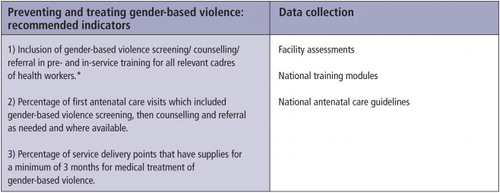

One of the main recommendations of the WHO Multi-Country Study on violence and women's healthCitation27 is to “use reproductive health services as entry points for identifying and supporting women in abusive relationships, and for delivering referral and support services”. Indeed all of the experts recommended that antenatal visits be used for gender-based violence (GBV) screening and referral whenever possible; hence indicator 2. We recognize that in most contexts this recommendation is aspirational and could not be immediately implemented everywhere because of a lack of health personnel trained to screen for GBV and/or a highly inadequate infrastructure to which women could be referred and receive they help that they need. WHO is currently developing guidelines on GBV which will provide important practical advice on this matter.

Medical treatmentFootnote† of sexual violence is defined as provision of pregnancy tests, emergency contraception, post-exposure prophylaxis for HIV and other STIs, and treatment of physical injuries. Indicator 3 refers to a functioning service delivery point,Citation28 defined as having staff currently (or within the last three months) treating violence against women with supplies adequate for three months (minimum) treatment. Referral includes service delivery points that can provide further medical treatment as appropriate as well as justice, shelter, and hotline services as appropriate to provide psychosocial support. In addition, GBV victims who become pregnant due to rape will need access to safe abortion services.

Our proposed indicators all relate to health because our focus is on metrics for health sector support agreements. However, we recognize that this subject crosses disciplinary boundaries. The Ministry of Health will normally have a more limited role in preventing GBV and a more extensive role in treating its consequences. It is important to advocate for medico-legal linkages that will enable both justice to be done in cases of GBV, and for the provision of health services for survivors. But as a recent article found in Kenya,Citation29 there were no linkages between medical and legal services. We recommend sharing country examples where this holistic approach has worked with Ministries of Health (MoH).

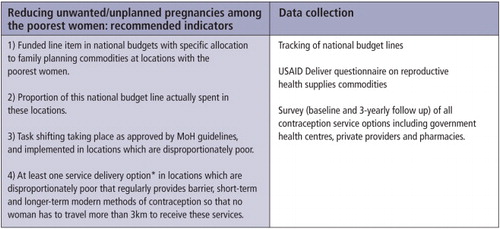

3. Reducing unwanted/unplanned pregnancies among the poorest women

We use the term “poorest women” to mean those that fall in the bottom 40% of income levels. Interviews with several MoH in Sub-Saharan Africa have confirmed that in many places governments and donors are already focusing on those localities that are disproportionately poor. Despite the push to increase contraceptive uptake to women overall, the poorest women are those least likely to have access to a wide range of family planning choices. A study using the most recent DHS from 30 countries showed that the likelihood of using modern contraception was twice as high for women with complete primary education than for those less educated, and it was higher for women with employment than for those without.Citation30 The disparity between the richest and the poorest seems to be increasing over time – DHS data from 55 countries has shown that despite increases in national averages, use of modern contraception by the poorest remains low, due among other factors to higher fertility preferences and lower availability of services.Citation31

To realistically assess progress in improving true access in those areas it will be necessary to have a baseline that accurately identifies the location of service delivery options within those specific localities. The experts recommended that this should include public health facilities, coverage by community-based and outreach workers, presence of service delivery NGOs, location of pharmacies and private doctors, and access to a steady supply of commodities. Several experts informed us that many countries in sub-Saharan Africa have this information already and the use of geographic information systems and data from relevant NGOs and medical associations should enable this baseline to be collected and maintained without being overly burdensome or expensive.

Indicator 2 is included on the recommendation of several experts because too often, budgets for contraceptives may be allocated but not spent. As for indicator 3, one of the main constraints on providing care to the most poor and those living in rural areas is the lack of adequately trained health care practitioners willing to live in those areas. Task-shifting, whereby different cadres of medical practitioners can provide an increasing amount of services, holds promise to increase access to contraception. Task-sharing, a similar concept where different levels of providers do similar work, is another option. Task-shifting can also encompass community-based distribution of services whereby local health workers can be trained in SRHR and mobile teams run by either the public or NGO sectors. In 2007, WHO developed guidelines for task-shifting related to HIV care;Citation32 it is currently developing similar guidelines for maternal health and family planning. Although both task-shifting and task-sharing have been tried over several decades, the concept of integrating them formally into national guidelines and training curricula is recent.Citation33 The process itself should not be seen as a panacea, but it is a welcome step towards reducing unwanted/unplanned pregnancies of the poorest women in areas with human resources shortages.Citation34

While there is guidance for minimum basic coverage of safe abortion,Citation16 no such guidance has been issued for minimum recommended coverage of family planning availability and experts had difficulty defining a practical measure for this. The proposed metric (indicator 4) is meant to be an illustration of what could be done in this area, suggested by one of the experts. Given that the largest amount of money by far in SRHR is allocated for family planning, the authors believe that it is very important to get to consensus on what constitutes adequate coverage.

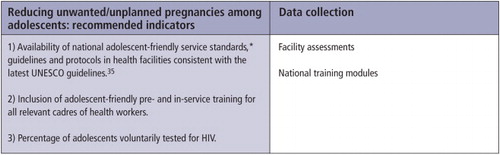

4. Reducing unwanted/unplanned pregnancies among adolescents

Adolescence is defined by WHO as the period between 10–19 years of age. Universally, it is a time of significant physiological and societal transition. Across societies worldwide, a range of cultural taboos exist towards sexual activity in young people, young women in particular. This is despite the fact that most people become sexually active before their 20th birthday.Citation36 Yet in many countries, laws and policies restrict access to information and contraception for adolescents (e.g. by requiring parental or spousal consent, or by limiting services to those over 16 years of age). The result is that adolescents carry a disproportionate burden of sexual and reproductive ill-health – they have low rates of modern contraceptive use (especially in poor young women), higher rates of sexually transmitted diseases as compared to other age groups, and a large proportion of unsafe abortions.Citation36 A recent article examining age-specific unsafe abortion globally has found that almost half (41%) of unsafe abortions in developing regions are among young women aged 15–24 years.Citation37

Worldwide, the prevalence of contraceptive use among young people is growing, but is characterised by shorter periods of use and higher rates of discontinuation,Citation38 due to adolescents having sex only intermittently, fear, embarrassment, lack of knowledge, lack of sensitivity/willingness of health care providers to provide services to young women and men, and the prohibitive cost of services.

Specifically for family planning, the Convention on the Rights of the Child and Rights to Sexual and Reproductive Health,Citation39 which several European governments have signed, states the need to develop youth-sensitive counselling, care and rehabilitation facilities that are accessible without parental consent for both married and unmarried adolescents.

We acknowledge that reducing unwanted/unplanned pregnancies in women under 20 years of age will require a holistic effort from different community actors including peers, the education sector, religious leaders, and parents, and will need to have a particular emphasis on those adolescents who are not in school. However, for the purposes of this review, we identify specific measures within the health sector that can be taken to improve the lot of adolescents. The rationale for indicator 3, from many of the experts, was that unmarried adolescents tend not to go to MoH facilities for contraceptives whereas they are more likely to go for HIV testing. Thus, this indicator would provide the health sector with a way to track services to unmarried adolescents who are having unprotected sex and thus vulnerable to both HIV and unplanned pregnancies.

Conclusion

Donors and governments want to allocate scarce resources where they will have the greatest impact. Evaluating how effectively that is happening requires metrics. If metrics are to inform future action, data must be collected reliably and analysed and interpreted insightfully, and commitment is needed from both donors and governments. This paper addresses the challenge of choosing practical measures of performance in the most telling areas – metrics that show whether and how much interventions are improving SRHR. Based on our discussions with the various experts, we believe that a reasonable consensus can be obtained from among the metrics presented in this paper.

These data are largely not collected today, or are collected unsystematically. Governments and donors must be willing to address the critical gaps in basic data collection, particularly for the poorest of the poor who tend to fall through the cracks in service delivery. We recommend analyzing the information, using the metric as a diagnostic tool – if there is a change in the metric over time, then that change should trigger a response to find out what has changed and why.

The performance measures we recommend are not designed to replace metrics currently used by individual donors or service delivery organisations, nor are they designed to add to the already heavy workload of MoHs. We also believe that focusing on a small number of indicators will be more practical than having a long list in terms of data collection and analysis and could also provide a clearer foundation for effective advocacy. We recognize that countries will need to adapt and interpret the indicators according to their national priorities. According to the ODA mapping study,Citation5 one critical and missing link in this picture is that NGOs do not have sufficient input into the design of health sector agreements nor into the areas of priority implementation. It is the opinion of the authors that without empowering SRHR NGOs to have a true seat at the table in health sector support agreements and design, gaining political commitment for these performance metrics will be difficult. The authors believe that it is the responsibility of donors and governments to invest in NGOs so that effective advocacy and monitoring for SRHR will take place at the country level.

Based on past experience, there is a long road to go down before good policies result in better programmes for women, and a still longer road for discernible improvements in SRHR. Unless there is general agreement on practical measures to assess progress, the experiences of the past will be repeated. In other words, attention and resources flow to those areas which will be measured and for which donors and governments will be held accountable. If SRHR measures are not included in major development frameworks, this area will continue to be starved of resources, ignored or worse.

The challenge is really not just the metrics but the commitment of donors and governments to hold themselves accountable to the women they are in business to serve. There is no one-size-fits-all or perfect SRHR metric. Rather, we believe that progress will be incremental and involve honest and constructive dialogue among donors, governments, SRHR NGOs and women in need of services. Our hope is that these metrics in some small way will make that accountability more feasible. We also believe that the SRHR field will be better prepared than in the past to be taken seriously as new development frameworks evolve if there are a small number of clear and measurable goals about which the field can agree and work together to support.

Notes

* They recommend that the 11 indicators should be reported for lowest wealth quintile, gender, age, urban/rural residence, geographical location and ethnicity, and where feasible and appropriate for education, marital status, number of children and HIV status.

* There were 45 African countries represented on the IHP+ website, but the remainder either had no SRHR indicators, no data available online, or were in Portuguese.

* Throughout the document, we refer to safe abortion care where it is legal, or post-abortion care for complications of unsafe procedures in legally restricted settings.

† The provision of medical supplies is in addition to the ability of service delivery points to have staff that are appropriately trained and supply counselling for gender-based violence. That aspect of care is addressed by the first GBV indicator.

References

- Santorius R. The logical framework approach to project design and management, evaluation practise. 1991;12(2):139–147.

- DFID business plan 2011–2015. www.dfid.gov.uk/Documents/DFID-business-plan.pdf.

- German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development. Minds for change. www.bmz.de/en/publications/type_of_publication/special_publications/Minds_for_Change.pdf

- World Bank. Program for results financing. http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTRESLENDING/Resources/7514725-1325006967127/WBbooklet12-21-11.pdf

- Multi-country studies at: www.dsw-online.org/odastudies.

- S Seims. Improving the impact of sexual and reproductive health development assistance from the like-minded European donors. Reproductive Health Matters. 19(38): 2011; 129–140.

- S Seims. Maximizing the effectiveness of sexual and reproductive health funding provided by seven European governments. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 37(3): 2011; 150–154.

- ICPD 15 Wellblog, SRHR: common ICPD monitoring indicators across countries. http://monitoringicpd15.wordpress.com/relevant-chapters-of-the-icpd-poa-cross-referenced-by-the-cross-country-indicators.

- Maputo Plan of Action. African Union Commission; 2007–2012. www.ippf.org/NR/rdonlyres/9D6A5F0E-F502-4BB7-BA40-49EAF7A0FFB7/0/Maputo_Plan_Action.pdf

- K Blanchard, B Elul, S RamaRao. Reproductive health indicators: moving forward. Population Council; 1999. www.popcouncil.org/pdfs/ebert/rhindicators.pdf

- World Health Organization. Reproductive health indicators for global monitoring, Report of the Second Interagency Meeting. 2000; WHO: Geneva. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2001/WHO_RHR_01.19.pdf

- World Health Organization. Monitoring maternal, newborn and child health: Understanding key progress indicators. www.who.int/healthmetrics/news/monitoring_maternal_newborn_child_health.pdf

- Health sector agreements, IHP+ Results website. www.internationalhealthpartnership.net/en/tools/country-planning-database.

- OECD. Evaluation and aid effectiveness No.6, glossary of key terms in evaluation and results-based management. www.oecd.org/dataoecd/29/21/2754804.pdf

- MJ Roseman, L Reichenbach. International Conference on Population and Development at 15 years: achieving sexual and reproductive health and rights for all?. American Journal of Public Health. 100(3): 2010; 403–406.

- World Health Organization. Safe Abortion: Technical and Policy Guidelines for Health Systems. 2012; WHO: Geneva. www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/unsafe_abortion/9789241548434/en/index.html

- World Health Organization. The prevention and management of unsafe abortion. Report of a technical working group. 1992; WHO: Geneva.

- G Sedgh, I Shah. Induced abortion: incidence and trends worldwide from 1995 to 2008. Lancet. 379(9816): 2012; 625–632.

- ICPD Programme of Action 1994. http://web.unfpa.org/mothers/consensus.htm.

- Ipas. Ensuring women's access to unsafe abortion: a key strategy for achieving the Millennium Development Goals. www.ipas.org/Publications/asset_upload_file557_2458.pdf

- J Solo, DL Billings, C Aloo-Obunga. Creating linkages between incomplete abortion treatment and family planning services in Kenya. Studies in Family Planning. 30(1): 1999; 17–27.

- Cited in Otsea K et al. Testing the safe abortion care model in Ethiopia to monitor service availability, use, and quality. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 2011. Doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.09.003.

- J Healy, K Otsea, J Benson. Counting abortions so that abortion really counts: indicators for monitoring the availability and use of abortion care services. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 95: 2006; 209–222.

- Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women, General Assembly resolution 48/104, 20 December 1993. www.unhchr.ch/huridocda/huridoca.nsf/A.RES.48.104.En/Opendocument.

- UNFPA. At: http://www.unfpa.org/gender/violence.htm. Accessed 22nd May 2012.

- C Watts, C Zimmerman. Violence against women: global scope and magnitude. Lancet. 359: 2002; 1232–1237.

- WHO. Multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence against women, summary report. www.who.int/gender/violence/who_multicountry_study/summary_report/en/index.html

- Adapted from Marie Stopes International RAISE programme.

- N Kilonzo, N Ndung'u, N Nthamburi. Sexual violence legislation in sub-Saharan Africa: the need for strengthened medico-legal linkages. Reproductive Health Matters. 17(34): 2009; 10–19.

- S Ahmed, AA Creanga, DG Gillespie. Economic status, education and empowerment: implications for maternal health service utilization in developing countries. PLoS One. 5(6): 2010; e11190. Doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011190.

- E Gakidou, E Vayena. Use of modern contraception by the poor is falling behind. PLoS Medicine. 4(2): 2007; e31. Doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040031.

- World Health Organization. Treat, train, retain: task shifting recommendations and guidelines. 2007; WHO: Geneva. www.who.int/healthsystems/TTR-TaskShifting.pdf

- B Janowitz, J Stanback, B Boyer. Task sharing in family planning. Studies in Family Planning. 43: 2012; 1.

- M Berer. Task shifting: exposing the cracks in public health systems. Reproductive Health Matters. 17(33): 2009; 4–8.

- UNESCO. International technical guidance on sexual education. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0018/001832/183281e.pdf

- A Blanc, A Tsui, T Croft. Patterns and trends in adolescents' contraceptive use and discontinuation in developing countries and comparisons with adult women. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 35(2): 2009; 63–71.

- I Shah, E Ahman. Unsafe abortion differentials in 2008 by age and developing country region: high burden among young women. Reproductive Health Matters. 20(39): 2012; 169–173.

- G Patton, C Coffey, S Sawyer. Global patterns of mortality in young people: a systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet. 374(9693): 2009; 881–892.

- Center for Reproductive Rights. Implementing adolescent reproductive rights through the Convention of the Rights of the Child. http://reproductiverights.org/sites/default/files/documents/pub_bp_implementingadoles.pdf