Abstract

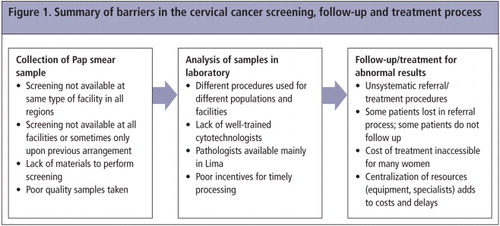

Through in-depth interviews with 30 key informants from 19 institutions in the health care system in four regions of Peru, this study identifies multiple barriers to obtaining cervical cancer screening, follow-up, and treatment. Some facilities outside Lima do not have the capacity to take Pap smear samples; others cannot do so on a continuing basis. Variation in procedures used by facilities and between regions, differences in women's ability to pay, as well as varying levels of training of laboratory personnel, all affect the quality and timing of service delivery and outcomes. In some settings, perverse incentives to accrue overtime payments increase the lag time between sample collection and reporting back of results. Some patients with abnormal results are lost to follow-up; others find needed treatment to be out of their financial or geographic reach. To increase coverage for cervical cancer screening and follow-up, interventions are needed at all levels, including an institutional overhaul to ensure that referral mechanisms are appropriate and that treatment is accessible and affordable. Training for midwives and gynaecologists is needed in good sample collection and fixing, and quality control of samples. Training of additional cytotechnologists, especially in the provinces, and incentives for processing Pap smears in an appropriate, timely manner is also required.

Résumé

Par des entretiens approfondis avec 30 informateurs de 19 institutions du système de santé de quatre régions péruviennes, cette étude identifie les multiples obstacles au dépistage, au suivi et au traitement du cancer du col de l'utérus. Certains centres en dehors de Lima ne peuvent prélever d'échantillons Pap, d'autres sont incapables de le faire de manière continue. Les différences dans les procédures utilisées par les centres et entre régions, les écarts dans la capacité des femmes à payer, ainsi que les divers niveaux de formation du personnel de laboratoire affectent la qualité et la ponctualité des services et de leurs résultats. Dans certains endroits, des primes perverses incitent à accumuler les heures supplémentaires, ce qui accroît les délais entre le frottis et la notification des résultats. Certaines patientes présentant des résultats anormaux échappent au suivi ; pour d'autres, le traitement nécessaire est hors de leur portée géographique ou financière. Pour élargir la couverture du dépistage et du suivi du cancer du col de l'utérus, il faut intervenir à tous les niveaux, avec notamment une restructuration institutionnelle pour garantir l'adéquation des mécanismes d'aiguillage et veiller à ce que le traitement soit accessible et abordable. Les sages-femmes et les gynécologues doivent apprendre à prélever et manipuler correctement les échantillons et à en contrôler la qualité. Il faut aussi former des cytotechniciens supplémentaires, spécialement en province, et inciter à un traitement ponctuel des prélèvements.

Resumen

Mediante entrevistas a profundidad con 30 informantes clave de 19 instituciones del sistema de salud, en cuatro regiones de Perú, este estudio identifica numerosas barreras para obtener pruebas de detección del cáncer (o cáncer del cuello uterino), seguimiento y tratamiento. Algunas unidades de salud fuera de Lima no tienen la capacidad para tomar muestras de Papanicolaou; otras no pueden hacerlo de manera continuada. La variación en los procedimientos utilizados por las unidades de salud y entre regiones, las diferencias en la capacidad de las mujeres para pagar, así como los diversos niveles de capacitación del personal de laboratorio, afectan la calidad y el tiempo de la prestación de servicios y los resultados. En algunos ámbitos, los incentivos para acumular pagos por horas extra aumentan las demoras entre la recolección de muestras y la rendición de informes de los resultados. A algunas pacientes con resultados anormales no se les da seguimiento; para otras, el tratamiento que necesitan resulta estar fuera de su alcance financiero o geográfico. Para aumentar la cobertura para la detección del cáncer cervical y el seguimiento, se necesitan intervenciones en todos los niveles, así como una revisión institucional para asegurar que los mecanismos de referencia sean apropiados y que el tratamiento sea accesible y a precios razonables. Las parteras y ginecólogos necesitan capacitación en la recolección y corrección de muestras, y control de calidad de las muestras. Además, es necesario capacitar a otros citotecnólogos, especialmente en las provincias, y ofrecer incentivos para procesar las muestras de Papanicolaou de una manera apropiada y oportuna.

Though cervical screening and treatment have successfully lowered cervical cancer incidence and mortality in developed countries, screening and treatment has not been as effective in Peru and other developing countries due to barriers to full programme implementation.Citation1–3 Cervical cancer is the most common cancer and the second cause of cancer-related deaths among Peruvian women.Citation4–7 In 2008, Peru's age-standardized incidence rate of 34.5 per 100,000 women and its cause-specific mortality rate of 16.3 per 100,000 women were each more than double the respective rates in the Americas as a whole.Citation8,9 Estimates of Pap smear coverage in Peru ranged from 7.0% to 42.9% in recent studies.Citation10–12

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), successful cervical cancer screening and treatment programmes must have high coverage of the at-risk population, appropriate follow-up and management for patients with abnormal test results, effective links between programme components, and adequate, high quality resources.Citation13,14 The Peruvian Ministry of Health (MINSA) declared cervical cancer reduction a national priority in 1998 with the National Plan for Cervical Cancer Prevention and Control, which was updated in 2007. The National Cancer Institute's 2008 Manual of Standards and Procedures for Cervical Cancer PreventionCitation15,16 mandates that all sexually active women aged 30–49 or women with at least one risk factor (including presence of HPV, sexual activity before age 18, multiple sexual partners, chronic cervicitis, history of sexually transmitted infection (STI), tobacco use and low socio-economic level) should have a Pap smear every three years.Citation15 Despite these policies, many women still never get tested, partly due to inadequate programme implementation.Citation1,2,11–13,17,18

A 2001 WHO consultationCitation13 associated the failure to lower cervical cancer incidence and mortality with political barriers, community and individual barriers, economic barriers, and technical and organizational barriers. These may all apply in Peru. Many women do not know what Pap smears are for or do not know that cervical cancer is treatable if detected in time.Citation19 Moreover, only some Peruvian women with abnormal results pursue the recommended follow-up and/or treatment.Citation5,20 This may be due to lack of available treatment for pre-invasive cervical lesions or even cancer. Not all cancer treatments are available outside Lima, yet many women cannot afford to go to Lima for treatment.Citation20 A cervical cancer screening programme cannot be successful with these limitations.Citation11,17,21–23

The objective of this study was to explore structural barriers to cervical cancer screening, follow-up and treatment in Peru, in order to propose recommendations which may reduce morbidity and mortality associated with cervical cancer here. We interviewed key informants from diverse institutions and with different roles relative to early detection and treatment of cervical cancer in four regions of Peru.

Methodology

Triangulation was key to understanding the data and synthesizing the results presented here. We interviewed individuals with diverse roles, from different institutions, and from different regions of the country. Moreover, as part of a larger study reported elsewhere, we also conducted focus group discussions with women from diverse backgrounds, to explore their knowledge and perceptions of cervical cancer and Pap smears,Citation19 and observed the health education provided to women by health care providers during clinic visits.Citation24

The study was carried out in four Peruvian cities with geographic and cultural diversity and socio-economic and demographic factors relevant to cervical cancer: Iquitos (rainforest, Loreto region), Huancayo (highlands, Junín region), Chincha (coast, Ica region) and metropolitan Lima (coast, capital city, home to one-third of the population). Poverty by region varied in 2007: 19% in metropolitan Lima and 15% in Ica, versus 43% in Junín and 55% in Loreto.Citation25 In the 2011 Peruvian Demographic & Health Survey (ENDES), 35% of women in Lima had completed secondary education, compared to 27% in Ica, 22% in Junín and 19% in Loreto. The median age at first sex was 16.6 among 20–49 year-old women in Loreto, 18.4 in Junín, 18.8 in Ica and 19.5 in Lima. The proportion of women not in union who reported two or more sexual partners in the previous year was 7% in Loreto, 3% in Lima and 2% in Ica and Junín.Citation26

The Peruvian health care system has three main sectors: the public Ministry of Health system (MINSA), the semi-public, employer-based social security system (EsSalud), and the private system. Each sector is independently organized and administered and has its own facilities: health posts, health centres, hospitals and specialized institutes, including the Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Neoplásicas (National Cancer Institute) in MINSA, health centres and hospitals in EsSalud, and private clinics. All systems also have laboratories within institutions and independent laboratories.Citation27

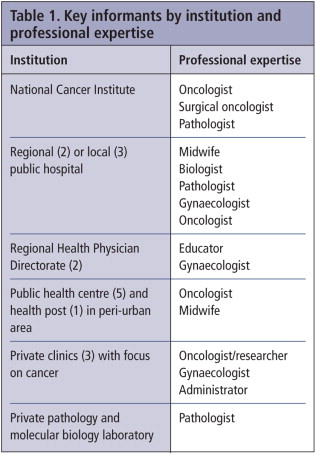

Thirty health professionals participated in this study (Table 1). Since the MINSA provides care for 76% of Peruvians, we focused on this sector.Citation27 We identified key informants from among national and regional governmental health policy officials, administrative personnel and health professionals who provide direct services to women, and lab technicians who carry out cytology. During the initial interviews, we used purposive sampling to identify other key informants on topics that required further exploration. The key was saturation: when we achieved understanding of what occurs during each step of the cervical cancer screening and follow-up process.Citation28

We carried out one semi-structured interview with each participant from June-August 2007, using a topic guide with open-ended questions, which varied with the interviewee's position and experience. Topics included key women's health issues; their perceptions of cervical cancer screening and treatment; their recommendations for improving screening and treatment processes, including sample taking, analysis of samples, provision of results and follow-up/treatment; and the strengths of and challenges related to each step in the process.

The interviews in Lima were carried out by three of the authors (AMB, LN, VAPS); interviews in the other sites were carried out by AMB and LN. All of the interviewers are fluent in Spanish and familiar with the country; VPS is Peruvian. Most interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim; in a few instances where the participant preferred not to be recorded, detailed notes were taken instead.

Prior to interview, participants consented to be interviewed and audio recorded. Approval was obtained from the Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine and the Peruvian NGO, Asociación Benéfica PRISMA, which all co-authors were associated with at the time of the study.

All interviews were analyzed to identify the most important themes, which were coded in ATLAS.ti.Citation29 The most important findings related to the following topics: awareness of a need for screening, collection of the cervical sample, analysis of the sample, and follow-up and treatment for abnormal results. Quotes from key informants are presented to reinforce significant messages.

Findings

Awareness of a need for screening

Almost all key informants perceived that women knew that Pap smears exist, but they do not get Pap smears due to taboos, fear and embarrassment; negative past experiences with the health system; and the absence of a culture of prevention. They emphasized cost was not an issue for women since Pap smears were low-cost or free for those with Comprehensive Health Insurance (SIS) in MINSA or EsSalud coverage. However, a midwife in peri-urban Lima suggested that economics does matter in that low-income women were so worried about how they and their families would live day-to-day that prevention was very secondary. Another midwife, from a public sector health centre in peri-urban Chincha said that women knew Pap smears exist, but had not received friendly, understandable information about what they were:

“No… it's not resistance… it's a lack of knowledge about what it is. So we explain to her what has to be done, how we take [the sample] and that it's not going to hurt… because the majority think, ‘Uyy, it's going to hurt, they're going to cut out a piece, they're going to pinch me on the inside.’ We explain to them in a simple way, ‘We're going to put in a speculum, it's a little uncomfortable, but it's not going to hurt’… Every time we take [a sample] we tell them, ‘It's better to know earlier than later.’”

Collection of Pap smears

Even though many health establishments reported that they collected and analyzed Pap smears, in practice this was not always true. First, there were inconsistencies in the type of facility that offered Pap smears across the study sites. Pap smears were offered routinely in most health centres in Lima, Chincha and Huancayo, but in Iquitos, women had to go to a hospital for this service because their local facilities were not adequately equipped. Second, even in facilities that stated they offered Pap smears, they might not be available all the time, especially outside Lima. Some facilities were unable to take a Pap smear unless the woman went to the facility to set up an appointment and returned another day for the smear. Third, many of the facilities lacked the materials necessary for taking smears, even in Lima. There were also administrative barriers, such as patients being refused a smear at a public health facility outside their own district.

Many informants – mostly those who worked in laboratories but some health care providers as well – complained about the poor quality of samples. There was a general consensus on the need for follow-up training and/or quality control for providers who took smears.

Another problem was that samples often came without a clinical history. Thus, those analysing the sample would not know whether it was the patient's first smear, a follow-up smear to an abnormal result or one following treatment to determine if it had succeeded. We asked if problems occurred in the sample taking or reading or both:

“In both… We have laboratories across Peru… We do work for [EsSalud]… Sometimes they have so many samples piled up that they invite bids… The Ministry of Health as well… Last year we won a bid to do all of the screening for a Department near Lima… We did it… but the samples were horrendous… They were poorly taken, poorly fixed… We couldn't read at least 40% of them.” (Pathologist, Private pathology and molecular biology laboratory, Lima)

“The problem is when we educate health professionals in this method… [trainers] tell them: ‘Take the Pap smear, put it on the slide and wrap it up.’ They don't take the time to observe the cervix, to see if there's a lesion, if there's bleeding, what characteristics it has… That's the problem.” (Oncologist, pilot cervical cancer screening programme, Public sector health centre, peri-urban Huancayo)

Laboratory analysis of samples

Depending on the institution's capacity and resources, as well as the patient's ability to pay, some samples were analysed in a lab within the facility, while other samples were sent elsewhere. Several informants mentioned the dilemma of where to have the samples analysed: in the facility where the smear was done or outsourced to Lima or a local private facility. Sending samples to Lima took time and incurred transportation costs, but was considered by some to be superior in terms of the quality of the analysis; outsourcing to a local private facility was less costly and usually provided more timely results.

In some cases, however, samples for those who could pay might be analysed locally at the hospital, so that those patients received their results more quickly. In contrast, samples for indigent patients might be outsourced; hence results took longer. Informants from all regions mentioned that women often did not return for the results or were even discouraged from getting a Pap smear at all when they knew results could take a month or more.

“The problem that we've had with results is that sometimes they take a long time… That's when the women don't come back for their results. The network laboratory is the point of reference for everyone… Sometimes it takes them as long as two months to give results… This needs to be faster.” (Service provider, Public sector health centre, peri-urban Lima)

“We haven't had a pathologist in several months. We've had to outsource the samples. They got lost… We have tons of problems… We try to do things and meet our goals, but in the process of getting the results back, a lot of things fail.” (Service provider, Semi-public sector hospital, Chincha)

“What we've shown is that the Pap smear is not reliable… I was trained at the National Cancer Institute and… my training tells me that… I have to have a Pap smear read by a pathologist… If it's not, it's not worth it.”

Follow-up and treatment for abnormal conditions

Many informants from all four regions complained that patients were not receiving proper treatment because neither the referral system nor the treatment procedures were systematic. Informants gave a wide range of estimates regarding the percent of women who needed treatment that actually received it: from as low as 30% to all of them. One informant commented that women did not routinely obtain Pap smears every three years as recommended; hence, when an abnormal result was detected, it was often severe because a lot of time had passed since the previous Pap smear, if any, allowing the cancer to progress. When a patient from a small or rural establishment had an abnormal result, she would be referred to the closest urban hospital to be seen by a specialist; this did not guarantee that the patient would be treated or that she would make it to the treatment facility. Moreover, referrals often exacerbated the gaps in treatment by creating new obstacles for the patient at a different institution in a hard-to-navigate system. One informant acknowledged: “They only return once they become seriously ill.”

Some institutions or individuals compensated for the lack of follow-up procedures. For example, some health providers covered patients' transportation, accompanied them to the hospital, or visited them at the hospital to guarantee that the women got treatment. Other informants mentioned that if the patient did not come for her follow-up, they went to her house.

The cost of treatment is rarely subsidized, hence it is out of reach for most. According to many informants, the system for indigent care only covers screening, not treatment, so the follow-up with these patients ends with the communication of results. An oncologist from the regional hospital in Iquitos described his perception of a common patient response:

“[We explain that] it is cancer, but it can be treated, with surgery, for example. But the psychology of the patient is not ‘I want to get cured, I don't have any money, but I want to get cured.’ No, the psychology is more like, ‘Well, I don't have any money, so I'd better just go home.’” (Oncologist, Regional hospital, Iquitos)

There was universal consensus that treatment expertise and equipment were highly centralized in Lima. Sometimes hospitals in the provinces did not have adequate or sufficient equipment to treat more advanced or persistent CIN and, even less so, cervical cancer. In other cases, they have the equipment, but administrative barriers resulted in inadequate use of resources. For example, one hospital's gynaecology department had equipment for conisations, but it was not shared with the oncology department. One informant mentioned that the local hospital in Iquitos did not have a pathology laboratory (despite interest in this), and there were no specialized oncological surgeons in the region.

If the cancer is advanced, the patient must be referred to the National Cancer Insitute, making treatment less accessible for the average woman living outside Lima, particularly if her treatment required several sessions (i.e. radiotherapy). The National Cancer Institute has a low-cost hotel for patients from the provinces to mitigate their costs, but as one informant commented, it was always full. An informant from Iquitos used his previous month as an example of the difficulties with follow-up: five patients had been diagnosed with cervical cancer; two went to Lima for treatment, the other three disappeared.

Finally, some informants attributed the problems associated with early detection to a lack of basic knowledge among patients and practitioners of all the steps in the process. Several informants complained that providers working in cervical cancer screening were unaware of local incidence of human papillomavirus (HPV) and its link to cervical cancer and were unfamiliar with the national protocol for CIN 1, which mandates follow-up Pap smears every six months for a year. Other informants mentioned that general practitioners – who are often a woman's point of entry into the health system – often don't emphasize to women the importance of cancer screening.

“The solution for countries like Peru is not the training… of specialists, but an improved ‘cancer culture’ in the general practitioner… As long as the general doctor doesn't have any idea about what stomach cancer, lung cancer, breast cancer, cervical cancer are… 80% of the cancers are going to arrive at the National Cancer Institute only when they're advanced. The first person that sees the patient is not the specialist. It's the general doctor… The doctor… has to understand that the patient isn't going to say, ‘Doctor, detect my breast cancer’… The doctor has to say that to her.”

Discussion

Barriers to increasing Pap smear coverage, follow-up and treatment for abnormal results were described by informants at every step in the process, summarized in . Two major problems that prevailed across the health system were the widespread lack of resources and the centralization of cervical cancer treatment, and even cytology services, in Lima.

The lack of a culture of prevention around reproductive health in Peru more generally has been documented before.Citation2 In one phase of this study, Peruvian women cited embarrassment and fear as the most common barriers to getting Pap smears.Citation19 In another phase, we observed numerous missed opportunities for health education on cervical cancer prevention within reproductive and sexual health services during clinician – patient interactions.Citation24 Key informants gave many reasons for the lack of prevention practices, from women not knowing about Pap smears to women not bothering because treatment will be prohibitively costly, to practitioners not educating women. We believe the Ministry of Health needs to create national awareness and public education to encourage preventive behaviours; this should include cervical cancer screening in the broader context of prevention related to all reproductive and sexual health care services such as family planning and antenatal care. As long as the country continues to rely on Pap smears to detect abnormal conditions, a national call and recall system that screens all eligible women will need to be instituted, as happens in high-resource countries.

As for sample collection and analysis, a change in the payment system is needed to incentivize good sample collection and analysis and prompt turnaround of results. Beyond training highly qualified cytotechnologists who remain in Lima, low- and mid-level technicians from other regions should be trained so that no samples have to be sent to Lima without first being analysed in-house.

The National Cancer Institute guidelines specify follow-up procedures for pre-cancers or cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN).Citation16 In addition to ensuring that there are trained professionals who are in place and following these guidelines, procedures are needed to ensure women are able to get treatment and be followed up as required. This means reducing bureaucratic obstacles at unfamiliar institutions and an unfamiliar city. Standard referral protocols, with a patient liaison officer who follows up with the patient, could be established to help women navigate the system. The barriers to treatment are exacerbated for women coming from outside of Lima, who will have to shoulder additional costs and difficulties associated with transportation to and lodging in Lima for treatment.

Unfortunately, as one informant said: “Cervical cancer attacks those with bare feet.” While cancer itself does not discriminate based on socioeconomic status, there are structural factors that cause class-related health disparities when cancer occurs. For example, an individual's motivation to seek screening for pre-cancerous lesions may be outweighed by her knowledge or belief that treatment might not be available or affordable. Indigent patients, who are more at risk for cervical cancer due to longer delays between Pap smears or lack of Pap smears at all, often have to wait longer for their screening results. The health care system should compensate for these disparities by seeking out strategies to make treatment (especially for pre- and early-stage cancers) more broadly available throughout the system and by prioritizing the analysis and delivery of screening results. Peri-urban and rural health care facilities may not have the equipment or expertise to analyse results on their own, but their budgets need to include outreach to follow up with patients and communicate results to those who do not return on their own. Some practitioners are already going above and beyond protocol to reach and treat patients despite obstacles; these practices should be standardized and incentivized.

Another option is to institute alternatives to Pap smears, such as universal provision of HPV vaccination. The Instituto de Investigación Nutricional, PATH and MINSA implemented an HPV vaccination demonstration project in fifth grade girls in schools on the northern coast of Peru in 2008.Citation30,31 The coverage rate was 83%, and non-vaccination was primarily due to absence from school. Concerns in the past that the vaccine would not be accepted because it was experimentalCitation32 appeared not to be a problem. In February 2011, the MINSA passed a Ministerial Resolution to provide the HPV vaccination scheme free to all 10-year old girls; its implementation began soon after.Citation33–35

Another issue raised in this research is whether adding VIA to the cervical cancer prevention protocol is appropriate for Peru. A recent analysis of obstacles to cervical cancer prevention in developing countries found that while some research deems novel screening technologies as the solution, this emphasis is more based on ideology than on the reality on the ground. The authors therefore recommend a concerted collaborative effort between public health workers and government officials in countries to introduce new strategies and technologies in conjunction with, but not necessarily instead of, existing ones, building on the infrastructure that already exists.Citation36

The results of a recent cervical cancer prevention intervention in Amazonian Peru (TATI) that employed HPV testing, VIA and conventional cytology confirmed some of the drawbacks to simply replacing Pap smears with VIA. For example, it demonstrated that HPV testing is more accurate than both VIA and conventional cytology, and that if VIA were employed as a strategy, it would require investment in regular training and supervision.Citation37

TATI-2 provided follow-up to TATI by using histology to test for CIN 2 and 3 and invasive cervical cancer in women who previously screened negative with VIA and Pap smears, and women who were previously unscreened with VIA. Results showed a lower prevalence of CIN 2-3 and invasive cervical cancer in previously screened women, implying that a single VIA screening can lower the population risk for cervical cancer.Citation38 These results are very important. However, there are significant problems in the referral for and costs of follow-up and treatment for abnormal results. Replacing Pap smears with VIA would not resolve these. Research is needed to determine which components would be the most cost-effective to invest in, to best use the limited resources available.

Even though Peru is classified as an upper middle-income country,Citation39 there is a disparity in resources by region. This qualitative study was not representative of the different regions of Peru or all Peruvian health professionals working to prevent, detect and treat cervical cancer, so we cannot generalize; however, there were clear indications that similar problems were shared by the three outlying regions versus Lima. We did not interview individuals responsible for cervical cancer policy and programmes within the Ministry of Health either. Lastly, we focused on barriers to screening and treatment of cervical cancer in Peru, but not the achievements in the system since cervical cancer was declared a national health priority in 1998 and national guidelines developed. Although data from Peru's Ministry of Health Epidemiology Office reveal that mortality associated with cervical cancer between 1987 and 2007 actually increased (from 9.6 to 11.4 per 100,000), this is likely to be a reflection of increased detection.Citation40

We can conclude that no single intervention will be sufficient to overcome the barriers to cervical cancer early detection and treatment. A major institutional overhaul is required, addressing every stage of the process, taking account of new strategies and technologies, health disparities between Lima and the rest of the country, women's needs and available resources.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the key informants for their time and insights. This research was possible thanks to funding from the Tulane Research Enhancement Funds.

References

- P Albujar. Cobertura citológica de la población femenina a riesgo de cancer cérvico uterino en la región La Libertad. Acta Cancerológica. 3: 1995; 113–115.

- PJ Garcia, S Chavez, B Feringa. Reproductive tract infections in rural women from the highlands, jungle and coastal regions of Peru. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 82: 2004; 483–492.

- A Solidoro, L Olivares, C Castellano. Cáncer de cuello uterino en el Perú. Diagnóstico. 43: 2004; 29–33.

- Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Neoplásicas. Perfil epidemiológico 2004. www.inen.sld.pe/portal/estadisticas/datos-epidemiologicos.html

- S Luciani, J Winkler. Cervical cancer prevention in Peru: lessons learned from the TATI demonstration project. 2006; PAHO: Washington, DC.

- Pan American Health Organization. Health in the Americas: 2007. 2007; PAHO: Washington, DC.

- WHO/ICO Information Centre on HPV and Cervical Cancer (HPV Information Centre). Human papilloma virus and related cancers in Peru. Summary report 2010. 2010; WHO/ICO: Barcelona.

- J Ferlay, HR Shin, F Bray. GLOBOCAN 2008 v2.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: International Agency for Research on Cancer CancerBase No.10. 2010; IARC: Lyon. http://globocan.iarc.fr

- GLOBOCAN World Health Organization International Agency for Research on Cancer. Section of cancer information, country fast stat 2008. http://globocan.iarc.fr/factsheets/populations/factsheet.asp?uno=604

- World Health Organization International Agency for Research on Cancer. IARC Handbooks of Cancer Prevention. Vol.10: Cervix cancer screening. 2005; IARC Press: Lyon.

- MJ Lewis. A situational analysis of cervical cancer in Latin America and the Caribbean. 2004; Pan American Health Organization: Washington, DC.

- VA Paz Soldán, F Lee, C Cárcamo. Who is getting Pap smears in urban Peru?. International Journal of Epidemiology. 37: 2008; 862–869.

- Programme on Cancer Control; WHO Department of Reproductive Health and Research. Cervical cancer screening in developing countries, report of a WHO consultation. 2002; WHO: Geneva.

- World Health Organization. Comprehensive cervical cancer control: a guide to essential practice. 2006; WHO: Geneva.

- Ministerio de Salud. Manual de normas y procedimientos para la prevención del cáncer del cuello uterino. 2000; Dirección de Programas Sociales, Programa Nacional de Planificación Familiar: Lima.

- Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Neoplásicas. Plan nacional para el fortalecimiento de la prevención y control del cáncer en el Perú. Norma técnico-oncológica para la prevención, detección y manejo de lesiones premalignas del cuello uterino al nivel nacional. 2008; INEN: Lima.

- R Sankaranarayanan, BA Madhukar, R Rajkumar. Effective screening programmes for cervical cancer in low- and middle-income developing countries. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 79(10): 2001; 954–962.

- S Arrossi, R Sankaranayarayanan, D Maxwell Parkin. Incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in Latin America. Salud Pública de México. 45(S3): 2003; S306–S314.

- VA Paz Soldán, L Nussbaum, A Bayer. Low knowledge of cervical cancer and cervical Pap smears among women in Peru, and their ideas of how this could be improved. International Quarterly of Community Health Education. 31(3): 2010–2011; 245–263.

- JL Hunter. Cervical cancer in Iquitos, Peru: local realities to guide prevention planning. Caderno Saúde Pública. 20(1): 2004; 160–171.

- Alliance for Cervical Cancer Prevention. Planning and implementing cervical cancer prevention and control programs: a manual for managers. 2004; ACCP: Seattle.

- J Bradley, M Barone, C Mahe. Delivering cervical cancer prevention services in low-resource settings. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 89(S2): 2005; S21–S29.

- JD Goldhaber-Fiebert, LE Denny, M De Souza. The costs of reducing loss to follow-up in South African cervical cancer screening. Cost Effectiveness and Resource Allocation. 3(11): 2005

- AM Bayer, L Nussbaum, L Cabrera. Missed opportunities for health education on Pap smears in Peru. Health Education & Behavior. 38(2): 2011; 198–209.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. Perú: Perfil de la Pobreza por departamentos, 2005–2007. 2008; INEI: Lima.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. Perú. Encuesta Demográfica y de Salud Familiar 2011 (ENDES). 2012; INEI: Lima. http://proyectos.inei.gob.pe/endes/2011/

- JE Alcalde-Rabanal, O Lazo-González, G Nigenda. The health system of Peru. Salud Pública de Mexico. 53(Suppl 2): 2011; S243–S254.

- MB Miles, AM Huberman. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. 1994; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks.

- ATLAS.ti, Version 5 [Computer Software]. 1999; Scientific Software Development: Berlin.

- M Penny, R Bartolini, NR Mosqueira. Strategies to vaccinate against cancer of the cervix: feasibility of a school-based HPV vaccination program in Peru. Vaccine. 29(31): 2011; 5022–5030.

- RM Bartolini, JK Drake, HM Creed-Kanashiro. Formative research to shape HPV vaccine introduction strategies in Peru. Salud Publica de Mexico. 52(3): 2010; 226–233.

- DS LaMontagne, S Barge, NT Le. Human papillomavirus vaccine delivery strategies that achieved high coverage in low- and middle-income countries. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 89(11): 2011; 821–830B.

- Ministerio de Salud (MINSA). Resolución Ministerial No. 070-2011. El Peruano. 2 February 2011. www.elperuano.pe/

- Ministerio de Salud. MINSA recomienda vacunar a niñas contra papiloma virus para evitar cáncer de cuello uterino. 2011 17 October. http://www.minsa.gob.pe/portada/prensa/notas_auxiliar.asp?nota=10702

- El Peruano. Inmunización avanzó 30%. 2012 12 May. http://www.elperuano.com.pe/edicion/noticia-inmunizacion-avanzo-30-19319.aspx

- EJ Suba, SK Murphy, AD Donnelly. Systems analysis of real-world obstacles to successful cervical cancer prevention in developing countries. American Journal of Public Health. 96(3): 2006; 480–487.

- M Almonte, C Ferreccio, JL Winkler. Cervical screening by visual inspection, HPV testing, liquid-based and conventional cytology in Amazonian Peru. International Journal of Cancer. 121(4): 2007; 796–802.

- S Luciani, S Munoz, M Gonzales. Effectiveness of cervical cancer screening using visual inspection with acetic acid in Peru. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 115(1): 2011; 53–56.

- World Bank. Data by country: Peru 2011. http://data.worldbank.org/country/peru

- Dirección General de Epidemiología, Ministerio de Salud. Análisis de la situación de salud del Perú 2010. 2010; MINSA: Lima. www.dge.gob.pe/publicaciones/pub_asis/asis25.pdf