Abstract

In spite of a number of communication campaigns since 1999 promoting modern contraceptives in Albania, their use remains low. In this paper we identify and analyse key barriers to the use of modern contraception among women in Albania. Semi-structured interviews with 11 stakeholders from organisations involved in promoting modern contraception, and four focus group discussions with 40 women from Tirana and a rural village in the periphery of Tirana, divided according to age and residence, were also conducted. Content analysis was used to analyse both the interviews and focus group discussions. Barriers identified included socio-cultural issues such as status of the relationship with partners and the importance of virginity, problems talking about sexual issues and contraception being taboo, health care issues — especially cost and availability — and individual issues such as unfavourable social attitudes towards contraceptives and a lack of knowledge about the use and benefits of modern contraception. To promote contraceptive use in the future, campaigns should address these barriers and expand from a focus on women of reproductive age only to target youth, men, health care providers, parents and schoolteachers as well.

Résumé

En dépit de plusieurs campagnes d'information menées depuis 1999 pour promouvoir les contraceptifs modernes en Albanie, leur utilisation demeure faible. Dans cet article, nous recensons et analysons les principaux obstacles à l'utilisation d'une contraception moderne chez les Albanaises. Des entretiens semi-structurés avec 11 acteurs d'organisations participant à la promotion de la contraception moderne et quatre discussions de groupe avec 40 femmes vivant à Tirana et dans un village rural de sa périphérie, divisées selon leur âge et leur résidence, ont été menés. Les entretiens et les discussions de groupe ont fait l'objet d'une analyse du contenu. Parmi les obstacles figuraient des questions socio-culturelles comme la situation de la relation avec les partenaires et l'importance de la virginité, des difficultés à parler de la sexualité et les tabous entourant la contraception, des problèmes de soins de santé, spécialement leur coût et leur disponibilité, et des préférences individuelles comme les attitudes sociales défavorables envers les contraceptifs et une méconnaissance de l'emploi et des avantages de la contraception moderne. Pour promouvoir la contraception, les futures campagnes devront s'attaquer à ces obstacles et cibler non plus seulement les femmes en âge de procréer, mais aussi les jeunes, les hommes, les prestataires de soins, les parents et les enseignants.

Resumen

Pese a varias campañas de comunicación iniciadas desde 1999 para promover los anticonceptivos modernos en Albania, su uso aún es poco frecuente. En este artículo se identifica y se analizan las barreras clave para el uso de anticonceptivos modernos entre mujeres en Albania. Se realizaron entrevistas semiestructuradas con 11 partes interesadas de organizaciones que promueven la anticoncepción moderna, y cuatro discusiones en grupos focales con 40 mujeres de Tirana y un poblado rural en la periferia de Tirana, divididas por edad y residencia. Mediante el análisis de contenido se analizaron las entrevistas y discusiones en grupos focales. Las barreras identificadas fueron: asuntos socioculturales tales como el estado de la relación con parejas y la importancia de la virginidad, dificultad para hablar sobre asuntos sexuales y el hecho de que la anticoncepción es tabú, asuntos de salud –especialmente costo y disponibilidad— y asuntos personales tales como actitudes sociales desfavorables hacia los anticonceptivos y falta de conocimiento sobre el uso y los beneficios de los anticonceptivos modernos. Para promover el uso de anticonceptivos en el futuro, las campañas deben eliminar estas barreras y dirigirse no solo a las mujeres en edad fértil sino también a jóvenes, hombres, profesionales de la salud, padres y maestros.

The International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo in 1994 was a landmark within the field of sexual and reproductive health. The Programme of Action committed governments to ensure that their populations have access to modern contraceptive methods.Citation1 In Albania, during 46 years of Communist rule (1945–1991), increases in the use of modern contraception, which occurred elsewhere in the world,Citation2 did not take place. The main reason was the regime's pro-natalist policies, in which modern contraceptives were banned, abortion was illegal and sex was considered a taboo topic.Citation3

In the early 1990s, the country underwent a transition to a market economy, which drastically changed the situation: modern contraceptives were introduced and abortion legalised. However, the distribution of modern contraceptives remained limited until the mid-1990s and studies showed that discussing sex was difficult; knowledge and awareness about sexuality and contraception were limited; and while the use of modern contraceptives had remained low during the 1990s, the number of abortions recorded skyrocketed.Citation3–7 People continued to rely on traditional methods, primarily withdrawal, to avoid pregnancy and resorted to abortion when necessary. Hence, in 2002, 8% of married women were using a modern contraceptive method while 67% were relying on withdrawal – many believing it was more effective at preventing pregnancies than modern methods.Citation3 Almost one in four pregnancies ended in abortion, at least 62% of which were induced.Citation8 Hence, since the transition, Albania has seen a continued drop in the total fertility rate to an estimated 1.6 in 2009.Citation9 To promote the use of modern contraceptives, a series of communication campaigns were carried out, starting in 1999. These were funded by foreign or international agencies such as USAID and UNFPA and implemented by both foreign and locally-based organisations, consultancy firms and other organisations.Citation10–13 In addition to a media component aimed at creating awareness, these campaigns have trained health care providers, pharmacists and journalists, worked to ensure contraceptive security and implemented inter-personal communication interventions.

By 2009, when this study was conducted, pills, condoms and injectables were being offered free of charge at public health facilities, and pills, condoms and emergency contraception were also available at subsidized prices at pharmacies through social marketing programmes.Citation7,9 Condoms could also be purchased at market prices through the commercial for-profit sector and tubal ligations and intrauterine device insertions were provided by obstetrician-gynaecologists.Citation9

Despite these efforts, the 2008–09 Demographic & Health Survey (DHS) found that there had only been a slight increase in the use of modern methods in the previous seven years, with only 11% of married women using them in 2009,Citation3,9 making Albania one of the countries with the lowest use of modern contraceptives in the European Region.Citation4,9 Moreover, 59% were still relying on withdrawal as their principal means of avoiding pregnancy.Citation9 Among sexually active unmarried women, 29% were using modern contraception (mainly condoms), but among unmarried 15–24 year-olds who were sexually active, 47–49% were relying on withdrawal. Women living in urban areas were only a bit more likely to use modern methods (12%) than women in rural areas. Women with higher education and women in the highest wealth quintile were more likely to use modern methods.Citation9 These findings imply that there are barriers to the use of modern contraceptive methods that either have not been addressed or have been insufficiently addressed by the communication campaigns. Alternatively, or in addition, other interventions may be required to effectively promote the use of modern contraception. This article aims to contribute to the design of targeted and tailored interventions by identifying and analysing the key obstacles Albanian women face in relation to the use of modern contraception.

Methods

We employed qualitative methods to collect information: semi-structured interviews with 11 stakeholders in the field of family planning and sexual and reproductive health in Albania, and focus group discussions with 40 Albanian women aged 15–50. The data collection took place in Albania in October–November 2009. This study was conducted for a Master's thesis, and we did not conduct focus group discussions with men due to limited time and resources. Ethical permission was granted by the Ministry of Health of Albania.

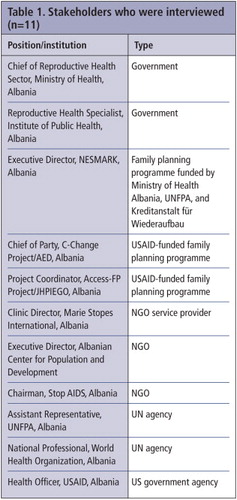

Purposive sampling was used to select participants. Initially, we drew up a list of organisations and individuals promoting family planning and sexual and reproductive health in Albania, identified through a literature and internet search. Whenever we conducted an interview we applied a rudimentary snowball sampling method, asking the informant if there were any relevant people missing on our list. This made it possible to sample informants who could shed light on other aspects of the topic than the initially identified informants. Two informants were added to the original list from these suggestions, resulting in 11 people interviewed (Table 1). The sampling was stopped when we no longer got new suggestions and theoretical saturation was reached.

We pre-tested the interview guide with a medical doctor working for one of the informant organisations. The interview guide contained mainly open-ended questions about their use of and experiences with the health communications campaigns promoting modern contraceptives (not reported in this paper) as well as the reasons they perceived for only 11% use of modern contraception, in spite of a number of campaigns aimed at increasing the use of contraceptives. The interviews were recorded and conducted in a location selected by the informants, usually their office.

The participants in the focus group discussions were selected using convenience sampling and were recruited through a trained peer student educator at the University of Tirana, two primary level health care providers, and a secondary schoolteacher. The peer student educator and schoolteacher were selected due to their easy access to younger women who do not necessarily attend health facilities, whereas the health care providers had good access to and knowledge of women over 25 years old who, for the most part, had already had children and attended the health facility. There were a total of 40 participants in four discussion groups. The women were divided into four groups by age and place of residence, two groups from Tirana and two from a rural village on the periphery of Tirana, as follows:

| • | Women under 25 years of age (9) in Tirana – they were 20–23 years of age and none of them had children. All of them were students at the university, the majority studying English. The discussion took place at a university dormitory in central Tirana. | ||||

| • | Women under 25 years of age (15) in a rural village – they were 17–18 years of age and none of them had children. All of them were students at the secondary school, where the discussion took place. | ||||

| • | Women over 25 years of age (7) in Tirana – they were 27–35 years of age and they all had children. Most of the women had studied at a college or university and were currently employed. | ||||

| • | Women over 25 years of age (9) in the rural village – they were 25–50 years of age and they all had children. All of them identified themselves as housewives. | ||||

The participants were informed about the purpose of the study, and consent to participate and to record the discussions was obtained. All of the women who were asked to participate agreed to do so and did participate. The focus group discussions were carried out at two primary level health centres, a secondary school classroom and a university dormitory. The interviews with the key informants and the discussion with the younger women in Tirana was conducted in English, as most of the participants spoke the language; direct translation into English for the discussion leader and into Albanian for the women by a translator was used for the other three groups. An interview guide with open-ended questions was used to facilitate the discussions. We tried to reduce the risk of misunderstandings and misinterpretations by carefully instructing the interpreters and asking the informants and focus groups participants beforehand if they felt comfortable with the process and the translation. The questions in the interview guide evolved around source of health information and the use of contraception, including reasons for using or not using a modern method, e.g. by young people.

The interviews and focus group discussions were transcribed immediately after they took place. Content analysis was used to analyse them. The transcriptions were manually searched for “meaning units”,Citation14 which were coded and categories generated by the first two authors independently. The categories were then combined and organised into core themes, e.g. availability of modern contraceptives. Any divergence in the categorisation and organisation into themes was resolved before they were reviewed, to ensure that there were no categories or themes that described the same phenomena.

Findings

The emerging barriers could be grouped into health care-related issues, socio-cultural issues and individual issues. These included cost and limited availability of contraceptives, the importance of virginity and the status of the relationship, taboos against talking about sex and about the wish not to become pregnant, and negative attitudes towards contraceptives, alongside limited knowledge of modern methods. Barriers were, in general, interlinked.

Health care-related issues

Issues mentioned relating to health care were mainly to do with cost and availability of modern contraceptives. Many of the key informants mentioned that modern contraceptives purchased at pharmacies and supermarkets were too expensive, which reduced access to them. Pills, condoms and injectables were distributed free of charge at government health centres, but several participants in the focus group discussions stressed that this did not necessarily make them easily available. The attitudes of the health care providers who distribute the methods play a key role here. Many of the informants and the participants in the focus group discussions noted that health care providers were often not supportive of modern contraception and sometimes avoided or refused to provide counselling and/or contraceptive methods to women. Some of the informants mentioned that this might be because they earned money performing abortions, and there was no economic incentive for them to counsel women to use a contraceptive.

The participants in the two focus group discussions for women aged less than 25 years also reported fears of being negatively judged if they went to a clinic for modern contraception. They said that they had “heard they distribute contraceptives for free in the family planning centres”, but that they were not sure, as no one their age would go there for that purpose. “It is easier to go to the drugstore or supermarket and buy them, rather than go there, because there are a lot of people and someone might see you.”

Moreover, some of the informants said that even where women had sought the advice of a health care provider, the advice would sometimes be wrong or misleading because the health care providers lacked knowledge. In cases where the health care provider was supportive and knowledgeable, availability might still be hampered by stock-outs of the products. “Since 2005 all the products have suffered from stock-outs. We don't have the money to buy the products. Even now we have a stock-out of emergency contraception” (Male informant, family planning programme organisation).

Socio-cultural factors

Socio-cultural factors were by far the most reported issues mentioned in the focus group discussions. One was the importance of virginity. In all four focus group discussions it was reported that it is a widespread notion in Albania that one should wait to have sex until marriage or at least until one is engaged. “If she is not a virgin, she is a bad girl.” It was also noted that this notion may be particularly prevalent in rural areas. The women older than 25 years in the rural village agreed. “If a girl has more than one partner then she is not a good girl and I would not like her as my daughter-in-law.” Similarly, the younger women's group in the rural village noted that “Albanian men are very interested in virginity” and when considering entering into a relationship “The first thing they ask us is: ‘Are you a virgin?’”

Yet, the younger women in both groups reported that this notion did not necessarily make unmarried women abstain from sexual relationships, but it did discourage some young women from using modern contraception. “They don't go to the drugstore to buy condoms or contraceptives because then the word will get out and everyone will know.” The importance of keeping it secret and thereby remaining a “good girl” was reported to outweigh the risk of pregnancy and STIs.

Once a woman is married or engaged, the situation changes. Then it was legitimate to have sex, but this also did not necessarily mean that couples started using modern contraception. Some focus group participants under 25 years stated that they relied on traditional methods to avoid pregnancy as “the methods for those who are engaged” precisely because they were engaged or married. Likewise, the women aged 25 and older in both urban and rural groups reported that “condoms are for young people, not for people who are parents” and that those who were married and had children should not use them. Instead these women said they preferred to use traditional methods, such as withdrawal.

The issue of being in a relationship also had an influence. The groups with women under 25 years stressed that being in a relationship and knowing one's partner made the use of contraceptives an issue of “avoiding pregnancy” and “not a problem of diseases”, revealing a perception that they were at low risk when it came to sexually transmitted infections. This made the use of condoms problematic as “condoms are seen as protecting you from sins and STIs rather than pregnancy” (Female informant, international development agency).

It was also widely reported in all four focus group discussions that for women in Albania, talking about sexual issues, contraception and having a boyfriend are to a large extent considered taboo. Young, unmarried women, for example, say they “can't go home and say ‘Mom, Dad, this is my boyfriend’”, and that “people are more comfortable when you say ‘Here is my fiancée’.” Again the way the relationship is labelled plays a role.

Moreover, the participants in the focus group discussions for women under 25 years reported feeling uncomfortable talking to their parents about sexual issues. The main reasons they gave were that the older generations were not used to talking about relationships, sex and contraception, not only because these issues were considered shameful and were illegal under Communism, but also because, as mentioned, young women were not supposed to have sex before marriage. Some of the respondents mentioned that such notions were more dominant in rural areas than in urban areas and that this was slowly changing as the country adapted to modern and western perceptions of relationships.

As with virginity at marriage, there was also a major gender difference when it came to talking about sexual issues. Thus, it was reported to be easier and not so unacceptable to talk to one's male children about sex, contraception and relationships. The participants from the focus group discussion for women over 25 years in the rural village agreed that they could freely discuss it with a boy, but that it would be difficult with a girl.

The informants and focus group participants were also asked if women in general could talk to their partners about sexual issues and contraceptives. The focus group discussions said yes, this was the case, although most participants preferred talking with their close friends about such issues. Nonetheless, the informants reported that although the level of discussion of the use of contraceptives and joint decision-making had improved over the years, it was far from satisfactory. “Sometimes the husband does not know that his wife is using contraceptives [pills or injectables]. Of course, there is a kind of freedom in discussing the issue, but not at the level of other European countries” (Female informant, international development agency). Some of the participants from the focus group discussion for women over 25 years in the rural village reported that they “would use something if my husband asked me, but my husband is not ready to use something”.

Individual factors

A number of more individual factors, such as attitude and knowledge related to contraceptives, were also reported. Attitudes towards contraceptives seemed to influence the use of a modern method. One prevalent attitude was that pills were less favoured compared to condoms and withdrawal, due to their perceived side effects. Side effects mentioned by the focus group discussion participants included weight gain, infertility and cancer.

However, the women also suspected that emergency contraception and IUDs could harm them and among the young focus group participants in Tirana it was mentioned that even condoms had harmful side effects, such as “the skin might not endure this rubber thing” and some thought that “using it a lot of times is not good for your health”.

Beliefs regarding side effects of modern contraception were frequently reported; however, many of the focus group participants also appeared bewildered and unable to separate fact from myth “because there are unreliable sources and you don't know who you can believe”. Besides hearing stories from the media, it was also mentioned that sometimes myths about modern contraception were passed on to children by their parents.

The fear of side effects was by far the most dominant attitude expressed by the women, but other aspects were mentioned as well, including that condoms are “uncomfortable”, but also considered ineffective because “it might be torn during the act”.

Knowledge about modern contraceptives was another issue touched upon in the focus group discussions and by the informants. It was noted that many women possessed inaccurate knowledge of modern contraception. Hence, although awareness existed about condoms and pills, knowledge was often inadequate to facilitate correct use, and as the benefits were often not understood, coupled with incorrect knowledge, personal use and support for other women was hampered. The discussions revealed diverging views on how knowledgeable young women were about these issues. Especially the over 25-year-olds in the rural area reported that young people already knew about these issues from school and it therefore was “not necessary to tell them because they are more informed than us”. However, in the discussions with those under 25 years it was reported that “girls do not know”, and that it would be good to know “how to use it and know the side effects and the benefits”. The participants in the group over 25 years in Tirana also mentioned “since the parents lack information they don't know what to give to their children” and therefore “don't communicate” with them about the use of contraceptives or related issues.

The lack of knowledge was in general attributed to a mentality stemming from the Communist period. The rural village women's group aged 25 and older, for instance, referred to the mentality from those times and noted that “All the people here use traditional methods because we do not have the education to use modern ways.” This “mentality” was also reported to have an impact on the support that young people received from their parents.

“Young people still have a mother, father, grandmother and grandfather who have received a totally different approach from the communist period. It is difficult to change behaviours if your parents are not supporting you. But I think things will change faster now because of the communications. Everybody has access to TV and telephone and young people travel, so I believe that it won't need ten years to change.” (Female informant, international organisation working with health communication and family planning).

Discussion

In this study we have identified a broad range of barriers which hamper the use of modern contraceptives among women in Albania, both among women younger and older than age 25, and women living in the capital and a rural village near the capital. We did not recruit participants who were currently living in remote rural areas, so their views were not represented. Yet the rural areas, including on the periphery of Tirana, together with those in the northeastern part of the country have the highest rates of infant and maternal mortality,Citation15,16 which may be due to less education, poorer health, poorer access to health care, lower use of modern contraception, unsafe abortion, or a combination of these.

This topic was clearly a sensitive one and may have affected the responses, especially among the participants in the focus group discussions, as they may have found it difficult to speak openly about it in settings where many people know each other, which is likely to have been the case at some level for the women from the rural village and the university students in Tirana.

In contrast to most other former Communist countries in Central and Eastern Europe, modern contraception and abortion were banned In Albania until about 20 years ago.Citation17 However, similar to many of these countries abortion has been an important determinant of fertility.Citation7,18 The barriers identified in this paper appear to be relics from previous pro-natalist policies and the socio-cultural norms they helped shape. Although Albania falls behind in the use of modern contraceptives they have a much higher proportion of married women who rely on traditional methods such as withdrawal compared to other Central and Eastern European countries,Citation9 probably because these methods have been the only ones they could utilize legally for several decades, and therefore have been handed down between the generations. This may also explain why the prevalence of modern contraceptive use in the urban vs. rural settings was not very different, 11% overall and 12% urban, and why there did not seem to be much of a difference between the two generations we talked to in the focus group discussions either.

In terms of issues related to provision of contraception, much has been done in the past 20 years to increase the availability of modern contraceptive methods: policies to legalise the methods and to ensure their availability have been developed and agreed,Citation7,16,19 and pills, condoms and injectables can increasingly be obtained free of charge at health care centres in AlbaniaCitation16,20 and at subsidised prices at pharmacies. Yet, from our study, it appears that socio-cultural perceptions make young, unmarried, unengaged women decide against obtaining modern methods, both because they fear being exposed as being in a sexual relationship and being judged as morally wrong for it.

In 1995, in a paper in Planned Parenthood Challenges, Albanian gynaecologist Eva Sahatci called for a new culture regarding sexuality, emphasising the need for information.Citation21 Though many of our informants and the focus group discussions noted that change has occurred since then, our study suggests that there is still a long way to go before we see a culture where married as well as unmarried women – not to mention men – can obtain modern contraceptives without fear of social condemnation and have access to the information and support they need to use the methods correctly and protect themselves from unwanted pregnancies and STIs.

This calls for increased training of health care providers to ensure they have the qualifications and practical training needed to provide quality counselling to women who need and want a modern contraceptive and enable them to select their preferred method based on informed choice. It also requires strengthening existing efforts to prevent stock-outs. More open discussion and public health education about sexuality issues, including on contraception, should be promoted, which could be done through strengthening the already existing peer educator programmes and sexuality education for young people in schools. It would help greatly if interventions targeting men, parents, schoolteachers and other key stakeholders such as politicians, in addition to (married) women of reproductive age.

This study was conducted three years ago, and Albania is undergoing rapid transitions in many areas. In 2010, another communication campaign on contraception was launched,Citation22 and the number of recorded abortions declined to the lowest number since the transition from Communism.Citation8 The Albanian Ministry of Health has developed a new national strategy for contraceptive security for the years 2012–2016, with the goal of increasing the use of modern contraceptive methods by 30% between 2008 and 2015, together with strategies to reach this goal.Citation23 These strategies acknowledge the need for additional efforts to be made to secure a sustainable supply of modern contraceptives and train health care providers. However, data reported in the strategy document show that the use of modern methods from 2009 to 2011 was fairly stable,Citation23 so there is still much work to be done.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dr Eva Sahatci for her valuable insights and help in collecting the data for this study.

References

- AC White, TW Merrick, AS Yazbeck. Reproductive Health. The Missing Millennium Development Goal. Poverty, Health, and Development in a Changing World. 2006; World Bank: Washington, DC.

- Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations. World Fertility Report 2003. 2004; UN: New York.

- L Morris, J Herold, S Bino. Reproductive Health Survey Albania, 2002. Final Report. 2005; Institute of Public Health, Albania Ministry of Health, Institute of Statistics, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: USAID, UNFPA and UNICEF.

- ASTRA Central and Eastern European Women's Network for Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights. Legal commitments to gender equality and SRHR issues in Albania, Macedonia, Georgia, Poland and Ukraine. 2009; ASTRA: Warsaw, Poland.

- B Dumani. Fertility and family planning in Albania. Planned Parenthood Europe. 22(1): 1993; 17–19.

- E Iliriani, P Asllani. Albania's students teach their peers about sexuality and safer sex. Planned Parenthood Challenges. 1: 1995; 37–38.

- NESMARK. The state of sexual and reproductive health in Albania. 2009.

- Albania Institute of Statistics. http://www.instat.gov.al/.

- Institute of Statistics, Institute of Public Health and ICF Macro. Albania Demographic and Health Survey 2008–09. 2010; Institute of Statistics, Institute of Public Health and ICF Macro.

- C-Change. Communication Strategy Phase I: February 2009 to July 2010. Tirana: C-Change; 12 December 2008.

- John Snow Inc. Final Technical Report: Strengthening Key Components. 2003; John Snow Inc: Tirana.

- John Snow Inc with Manoff Group. Strategic Framework. Albania Family Planning Project 2004–2006. 2005; John Snow Inc with Manoff Group: Tirana.

- NESMARK. http://nesmark.org.al/about.html.

- UH Graneheim, B Lundman. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today. 24(2): 2004; 105–112.

- UNICEF. http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/albania_statistics.html.

- The Europe and Eurasia Regional Family Planning Activity. Albania: Family Planning Situation Analysis 2007. John Snow Inc/Europe and Eurasia Regional Family Planning Activity for US Agency for International Development; 2007.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, ORC Macro. Reproductive, Maternal and Child Health in Eastern Europe and Eurasia: A Comparative Report. 2003; Calverton, MD.

- USAID, PSP-one. The private sector contraceptive market in Albania: a rapid assessment. USAID, PSP-one; 2008.

- D Islami, F Kallajxhi, O Gliozheni. Reproductive health in Albania. http://www.gfmerch/Endo/Reprod_health/Reprod_Health_Eastern_Europe/albania/ALBANIA_ISLAMI_html

- Ministry of Health, Albania, UNAIDS, Institute of Public Health. Let's keep Albania a low HIV prevalence country. National Strategy of Prevention and Control of HIV/AIDS in Albania 2004–2010. 2003; Ministry of Health: Albania.

- E Sahatci. The fight for reproductive rights in Central and Eastern Europe. Albania: discovering the human right to family planning. Planned Parenthood Challenges. 2: 1995; 25–26.

- C-Change. http://c-changeprogram.org/where-we-work/albania.

- Ministry of Health, Albania. National Strategy of Contraceptive Security 2012–2016. December. 2011; Albania.