Abstract

Adolescent pregnancy places girls at increased risk for poor health and educational outcomes that limit livelihood options, economic independence, and empowerment in adulthood. In Tanzania, adolescent pregnancy remains a significant concern, with over half of all first births occurring before women reach the age of 20. A participatory research and action project (Vitu Newala) conducted formative research in a rural district on the dynamics of sexual risk and agency among 82 girls aged 12–17. Four major risk factors undermined girls' ability to protect their own health and well-being: poverty that pushed them into having sex to meet basic needs, sexual expectations on the part of older men and boys their age, rape and coercive sex (including sexual abuse from an early age), and unintended pregnancy. Transactional sex with older men was one of the few available sources of income that allowed adolescent girls to meet their basic needs, making this a common choice for many girls, even though it increased the risk of unintended (early) pregnancy. Yet parents and adult community members blamed the girls alone for putting themselves at risk. These findings were used to inform a pilot project aimed to engage and empower adolescent girls and boys as agents of change to influence powerful gender norms that perpetuate girls' risk.

Résumé

La grossesse accroît le risque de mauvais état de santé et de résultats scolaires médiocres chez les adolescentes, ce qui limite leurs moyens de subsistance, leur indépendance économique et leur autonomisation à l'âge adulte. En République-Unie de Tanzanie, la grossesse des adolescentes demeure une grave préoccupation, plus de la moitié des premières naissances se produisant avant que la femme ait 20 ans. Une recherche participative et un projet de mobilisation (Vitu Newala) a mené une analyse formative dans un district rural sur la dynamique de l'activité et des risques sexuels parmi 82 adolescentes âgées de 12 à 17 ans. Quatre principaux facteurs de risque compromettaient la capacité des jeunes filles à protéger leur santé et leur bien-être : la pauvreté, qui les incitait à avoir des relations sexuelles pour satisfaire leurs besoins essentiels, les attentes sexuelles de la part d'hommes plus âgés et d'adolescents, le viol et les rapports sexuels forcés (y compris les abus sexuels à un jeune âge), et les grossesses non désirées. Les rapports sexuels monnayés avec des hommes plus âgés, l'une des rares sources de revenu qui permettent aux adolescentes de satisfaire leurs besoins essentiels, étaient un choix fréquent de nombreuses filles, même s'ils augmentaient le risque de grossesse (précoce) non désirée. Pourtant, les parents et les membres adultes de la communauté tenaient les filles pour uniques responsables des risques encourus. Ces conclusions ont guidé un projet pilote visant à engager et autonomiser des filles et des garçons comme agents du changement pour influencer de puissantes normes sexuelles qui perpétuent les risques pris par les filles.

Resumen

El embarazo en la adolescencia coloca a las niñas en mayor riesgo de tener mala salud y consecuencias educativas que limitan sus opciones de sustento, independencia económica y empoderamiento en la adultez. En Tanzania, el embarazo en la adolescencia continúa siendo una gran preocupación, ya que más de la mitad de todos los primeros nacimientos ocurren antes que las mujeres cumplen 20 años de edad. En un proyecto de investigación-acción participativa (Vitu Newala), se realizó un investigación formativa en un distrito rural sobre la dinámica del riesgo y actividad sexuales entre 82 niñas de 12 a 17 años de edad. Cuatro factores principales de riesgo debilitaron la capacidad de las niñas para proteger su propia salud y bienestar: la pobreza, por la cual se vieron obligadas a tener sexo para cubrir sus necesidades básicas; las expectativas sexuales tanto de niños de su edad como de hombres de edad más avanzada; violación y sexo forzado (incluido el abuso sexual a temprana edad); y el embarazo no intencional. El sexo transaccional con hombres de edad más avanzada era una de las pocas fuentes de ingreso que les permitía a las adolescentes satisfacer sus necesidades básicas, por lo cual era una opción común para muchas niñas a pesar de que aumenta el riesgo de tener embarazos no intencionales (a temprana edad). Sin embargo, los padres e integrantes de la comunidad adulta culpaban solo a las niñas por ponerse en riesgo. Estos hallazgos se utilizaron para informar a un proyecto piloto cuyo objetivo era empoderar a las y los adolescentes como agentes de cambio para influir en importantes normas de género que perpetúan el riesgo de las niñas.

Adolescent pregnancy places girls at increased risk for poor health outcomes, including unsafe abortion, difficulty during childbirth, pregnancy-related mortality and morbidity, and HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs).Citation1,2 Adolescent girls who become pregnant also face a greater risk of poor educational outcomes, including school dropout, which is linked to curtailed livelihood options and limited economic independence.Citation3,4 Adolescent pregnancy is also predictive of lower levels of empowerment in adulthood, manifested as higher acceptance of wife beating and less decision-making parity within marital relationships.Citation5

In Tanzania, adolescent pregnancy is a significant concern, with nearly one third of women (28.4%) giving birth by the age of 18, and over half (56.4%) of all first births occurring before women reach the age of 20.Citation6 National Demographic & Health Survey (DHS) data for the five years to 2010 show that an estimated 25% of all pregnancies in Tanzania are unplanned.Citation6 Among Tanzanian women under the age of 20, 26.6% have had at least one recent birth that was wanted later than at the time of pregnancy.Citation7 While some unintended pregnancies result from a lack of awareness and use of contraceptive methods and sources, they are also due in large part to an array of social and structural inequalities that compromise sexual decision-making among adolescent girls.Citation8

Some of the most influential factors that explain girls' heightened vulnerability to unintended pregnancy are multiple concurrent partnerships, cross-generational and transactional sex, and sexual violence.Citation9–11 Among Tanzanian girls 15–19 years of age, nearly a quarter (23.8%) had experienced violence since the age of 15, and 13.2% reported at least one experience of sexual violence. Ten per cent of Tanzanian women 15–49 also reported that their first sexual experience was forced, and this proportion was even higher when sexual initiation before the age of 15 was included.Citation3 A multi-country study on violence found that in a sample of 1,100 women in provincial Tanzania, forced first sex was reported by 17% and 43% of these reported having experienced this before the age of 14.Citation12 Another study in Tanzania found that of 127 adolescent respondents who had ever had sex, a quarter had done so for financial or material gain.Citation13 Whether viewed as an autonomous choice made to keep up with their peers and for material goods or as a decision made in the absence of any other options for meeting their basic needs, engaging in transactional sex is very common among adolescent girls across sub-Saharan Africa.Citation14–16

At the heart of these data lies the reality that girls' lives are shaped by gender inequalities and gender norms that have a negative impact on their social and sexual interactions and severely limit their power to negotiate whether, when and with whom they have sex and how safe it is.Citation17,18 But girls' lives and the prescribed gender roles and disempowerment to which they have traditionally been relegated are amenable to change. Throughout Tanzania, there is now increasing attention by programmers, policymakers, and donors to tapping girls' potential for achieving not only prevention of HIV and early pregnancy, but broader health, safety and development goals as well.Citation19,20

This paper presents findings from a formative research and action project that explored the dynamics of sexual risk and agency among 12–17 year old girls. It also describes how the findings were used to inform a pilot project (Vitu Newala) that aimed to engage and empower adolescent girls and boys as agents of change in order to influence powerful gender norms that perpetuate risk.

Setting

The work took place in four rural, widely dispersed communities in Newala, an under-served district in southern Tanzania's Mtwara Region. While basic services are increasingly available and the communications infrastructure has witnessed improvements in recent years, these improvements do not extend into the communities surrounding Newala town. Data from Newala are very limited, but the education and health infrastructure are widely considered to be among the weakest in the country. School dropout rates are thought to be higher in Newala than in the rest of Mtwara Region. DHS data show that women in the Southern zone of the country, where Mtwara is located, consistently have among the highest rates of teen pregnancies, multiple sexual partners and transactional sex.Citation6 Across Tanzania, the percentage of girls 15–19 who had already experienced a live birth was 17.2%, with the lowest percentage (13.4%) in the Northern zone and the highest (20.4%) in the Lake zone. Girls in the Southern zone have among the highest percentage of teenage births, at 19.7%. When combined with the proportion who were experiencing a first pregnancy at the time of the DHS, 25.5% of girls in the Southern zone had begun childbearing before the age of 19, compared to a national average of 22.8%. Similarly, the proportion of girls in rural areas who have begun childbearing by 19 was much higher (26.3%) than among their peers in urban areas (14.6%). Compelled by this harsh reality, rural Newala and its surrounding wards were chosen as the site of this project.

Methods

The research was carried out as a series of participatory learning and action (PLA) exercises, in which the research team facilitates group activities aimed at generating discussion, data, and decisions by community members about issues of relevance to their daily lives.Citation21 These sessions were led by nine young women 18–24 years who had been nominated by representatives of the Newala NGO Network in their communities to be trained as Youth Researchers. The training was provided by the International Center for Research on Women (ICRW) and Taasisi ya Maendeleo Shirikishi Arusha (TAMASHA), a Tanzanian NGO, in the week prior to fielding the research. In each of the four communities, the youth researchers carried out two separate PLA exercises, one with younger girls (aged 12–14 years) and one with older girls (aged 15–17 years). A total of 82 girls participated in PLA sessions in the four communities, of whom 59 were enrolled in school at the time of the research. Eight girls reported that they had at least one child, and of these, none were in school and one was married. Only four of the girls reported living with two parents who were earning an income, while 33 reported that their mothers were the primary source of household income.

Basic sociodemographic information was collected on all participants, but the girls were not asked to report on their own experiences with sex, pregnancy, or violence. Rather, a variety of participatory exercises were used to elicit information about their aspirations for the future, their attitudes about sex and gender-related expectations, and the challenges girls in their communities faced in relation to HIV/STI prevention. Key activities in the participatory sessions included: drawings of dreams, discussion of obstacles to those dreams, voting on statements about gender roles and behaviours in the community, free listing and ranking of perceived HIV-related risks, mapping of the dangerous areas in the community, and identifying and prioritizing solutions for reducing these risks. A team of trained adult researchers from TAMASHA also conducted three focus group discussions and 3–5 key informant interviews with male and female adults in each community – a total of 140 parents, community leaders, service providers – to document their views about the girls' sexual decision-making and the role the community could play in safeguarding girls' health and well-being. Adolescent boys were not included in the participatory research but were incorporated in the subsequent pilot project. Ethical approval was granted by the Institutional Review Board of ICRW and the Tanzanian Commission for Science and Technology (COSTECH), a Tanzanian ethical review board for the social and health sciences.

The findings from this research were synthesized and presented by TAMASHA and the Youth Researchers to community leaders, including elected officials, traditional leaders, and civil society stakeholders at the district, ward, and community levels in a validation workshop. This workshop took place over the course of two days to share key findings and encourage dialogue about the solutions proposed by adolescent and adult participants in the PLA sessions, key informant interviews and FGDs. Quotes from participants reflect commonly expressed views.

Findings

The findings shed light on a host of risks to the sexual health and social well-being of adolescent girls in these communities, including poverty, sexual expectations on the part of older men and boys their own age, rape and coercive sex, and unintended (early) pregnancy. Overwhelmingly, girls' aspirations centred on having families, small businesses, and a home of their own, and PLA participants felt that early pregnancy and being unable to finish secondary school were the greatest threats to their dreams.

Poverty and sexual risk

The participatory sessions with girls revealed that, due to economic migration of income earners and parents' divorce, adolescent girls in Newala are often expected to take on the role of providing school fees, food, clothing, health care and transportation for themselves and their siblings. To cope with this early transition to an adult role, girls have very limited options for dealing with these basic needs. Often, they opt for transactional sexual relationships with older men who are willing to provide for some of these needs.

“The parents leave the children with nothing and so the big sister has to go and find a way to provide for them. She's still a child, so the only way she can buy things is if she goes with a man.” (PLA participant, 12–14 year old group)

“I will have sex to get those basic needs I am lacking.” (PLA participant, 12–14 year old group)”

As another result of their families' economic realities, many girls said girls were forced to consider early marriage, which also puts them at risk. Girls whose basic needs were not met at home might accept marriage at an early age to relieve the economic burden their care and support places on their birth family.

“There's nobody to take care of her or send her to school. So, she accepts a husband so that she can have food, clothes, and soap. Just the basic things.” (PLA participant, 15–17 year old group)

“They see that their friends have nice body oils and cosmetics because lovers buy it for them. They want to have those things, too, so they do what their friends do.” (Nurses group)

“She goes out and has sex with a man, but it's not to help the family, it's because of her greed. She wants him to buy her presents and give her money.” (Mother, FGD)

“She goes and has sex somewhere and in the end returns home. We don't benefit at all, no salt, no ‘mboga’ she comes home empty handed.” (Mother, FGD)

Sexual expectations on the part of men

In the context of family poverty and limited economic options, girls' sexual decision-making appears to be influenced by gendered social norms dictating roles and behaviours for girls, which have a strong influence on sexual risk-taking. Respondents in both age groups revealed that there was nearly constant pressure from men and from their male peers to have sex, which permeates girls' daily experiences, and perpetuates strong gendered expectations about the sexual roles that they are allowed to play within their cultural context.

“If a man sees you outside, he'll approach you and ask you to go with him. Even if you say no, he'll ask every day and you have to find a way to refuse without making him angry.” (PLA participant, 12–14 year old group)

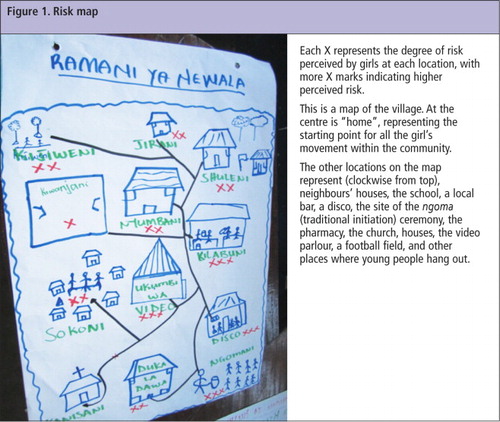

Adult participants in the validation workshop were surprised by the extent of risk represented by this map:

“When I look at the map, the only safe places I see are the church and the mosque. So where do we expect these girls to live?” (District leader, validation workshop)

“If the girl has to say ‘no’ 20 times today, maybe tomorrow she will have a problem.” (District leader, validation workshop)

“It is a normal thing for a man to seduce a girl and it is not easy for a man to stop trying again and again even if a girl refuses him.” (Father, FGD)

“I think she is the one who's most to blame because she shouldn't accept gifts and things from him. She should know he will expect her to have sex if she takes money and gifts from him.” (Woman from the community, validation workshop)

Rape and coercive sex

One of the immediate consequences of the daily harassment girls said they faced was the very real risk of sexual violence. Girls frequently cited the persistent pressure from boys and men to have sex as, ultimately, a decision between giving in or being raped.

“You might decide to say yes after saying ‘no’ so many times because you know that he will just force you in the end.” (PLA participant, 15–17 year old group)

“Some men decide they have to have a girl even after she has refused him. They get together with their friends and carry her off to rape her. Sometimes they all take turns raping her.” (PLA participant, 15–17 year old group)

“If a boy wants you for sex, he will get you no matter how many times you say ‘no’ to him and try to avoid him every time you see him coming near. It doesn't matter if you don't want him, it matters that he wants you.” (PLA participant, 15–17 year old group)

Girls also explained that even when girls willingly engaged in a (sexual) relationship, they were unable to control whether and when they had sex. While also not defined by participants as “rape”, early initiation of sex with girls was revealed to be common, even prior to the onset of puberty and with girls as young as the age of eight.

Unintended (early) pregnancy

Although our purpose in launching this study was to learn about risks related to HIV and other STIs, the prevention of unintended and early pregnancy was consistently mentioned as the most pressing concern by both parents and adolescent girls.

“We know about HIV and using condoms to avoid it, but right now we have to make sure we don't get pregnant. If we do, we can't finish school and we'll just be at home with people calling us names all the time.” (PLA participant, 12–14 year old group)

The overriding feeling among participants was that early pregnancy posed immediate social consequences including stigma, rejection by parents, and school dropout. Abortion is not a legal option in Tanzania, and access to safe abortion is very limited. In Newala, abortion is often attempted using traditional methods (i.e. ingesting strong herbs or inserting a cassava root into the vagina) or is sought out through costly and often unsafe providers. Despite acknowledging the danger of unsafe abortion, the 15–17-year-old participants made explicit reference to abortion as a way of dealing with an unintended pregnancy.

“If you are young and you get pregnant, you might get an abortion so your parents aren't disappointed and don't punish you. But it's expensive and so you have to hope that your lover will pay for it so your parents don't find out.” (PLA participant, 15–17 year old group)

“The way these children start having sex at an early age and the tamaa they have for money, they have no power to tell a man to use a condom and so they don't use condoms.” (Mother, FGD)

“We are providing free condoms here, but those who are coming to take them are those boys in secondary school. This is because they are afraid of getting girls pregnant and disturbing their studies, also because they don't have money for abortion.” (Nurse, FGD)

“Recently, a child of about 10 years came with her Depo-Provera and wanted me to inject her and when I asked her where she got it she told me from a pharmacy…The majority of those who sign up for these services are children rather than adults.” (Nurse, FGD)

While girls may seek out contraception on the advice of friends and without parental consent, parents also reported seeking contraception for very young daughters they suspected or knew were sexually active. Some parents and community members condoned this early use of contraception, in part because it allowed these girls to stay in school and pursue their education.

“After her puberty, I was always afraid when she left the house that she would come back pregnant. That's when I decided to get her injections to make sure she wouldn't get pregnant before she finished her schooling.” (Mother, FGD)

Discussion

While this research was intended to explore girls' risk for HIV, both adolescent and adult participants recognised the extent of rape and sexual coercion and expressed far greater concern about preventing early pregnancy. At the core of this issue is a tension between sexual agency and sexual victimization, through which girls are at once understood to be taking on partners and seeking partners to meet their material needs and desires, but also have very limited power in even the most basic decision about whether to have sex with someone or not.Citation15,16 This tension is illustrated clearly through the currents of blame for tamaa and how it is dually seen as being utilized by and imposed upon girls. The strong pressure girls feel to contribute to and provide for the family gives mixed messages about whether or not they should aspire to use tamaa, even for the good of their families. There is little open acknowledgment by adults of parents' own complicity in this cycle of risk and blame, let alone the role of men and boys in powering it.

These findings further underscore an important disconnect between adolescents and the adults in their families and communities, from whom they face contradictory expectations about their sexual behaviour. While traditional social norms dictate that girls refrain from having sex until they are adults, preferably until they are married, they receive contradictory messages from men who approach them for sex and from the adults charged with their care. A mother who requests contraceptive injections for her adolescent daughter is also acting within a constrained set of choices to prevent her daughter from becoming pregnant, as this is seen as the most important outcome to avoid for her adolescent daughter. And while supporting a daughter's contraceptive use is an important step toward preventing unintended pregnancies, mothers have indicated they are not in a position to provide girls with the skills they need to avoid sexual violence, make informed decisions about contraception, negotiate with a partner even when the sex may be consensual, or to protect themselves from HIV and other STIs.

As a result of the mixed messages they receive and their own powerlessness, girls felt they alone were responsible for fending off men's advances and for preventing pregnancy. Throughout the formative research process girls consistently expressed a sense of being voiceless in their communities in the eyes of men, and with their parents, their peers, and this was confirmed by older community members. This sense of powerlessness had a direct impact on whether and how they sought support when they faced difficult situations, and ultimately whether they had the intrapersonal and/or interpersonal resources available to help them navigate decisions about their sexual health and relationships.

A few important limitations of these findings should be noted. The sample of girls who participated in PLA exercises was small and not representative. Given that recruitment was conducted through a community partner in some of the most accessible wards of Newala, some selection bias is possible. However, girls in more remote, less resourced areas are likely to face even starker challenges and choices than those who participated in this study. Another important limitation is that girls were not asked to report on their own experiences but rather to discuss what challenges girls in their communities face. While this was intended to avoid potential stigmatization, it also means that reported behaviours and norms may be more perceived than real. The study's original framing around risk and vulnerability to HIV also did not result in adequate exploration of girls' desire for sex though it did bring out in great detail the sexual risks they faced. Finally, while the study did capture the opinions of parents and local elected and traditional leaders, it was limited in its representation of the perspective of adolescent boys and of the men whose sexual advances were so frequently discussed.

Despite these limitations, the findings from this study highlighted the importance of understanding and addressing the underlying causes of and influences on girls' sexual behaviour.Citation22 To do so requires that we place the young people themselves at the centre of both research and programming agendas, not as passive recipients but as active contributors.

Pilot project to test a life skills curriculum

These insights were used to inform the development of Vitu Newala, a pilot project designed by the Youth Researchers, in collaboration with ICRW and TAMASHA, which involved adolescent girls and boys as Peer Facilitators as well as female and male adult Guardians nominated by youth in their communities as supporters of youth rights. Both the Facilitators and the Guardians received training on a tailored Life Skills Education curriculum designed to enhance the self-efficacy of adolescent girls and boys to navigate sexual decision-making and interpersonal communication, and to develop leadership skills. By employing this inclusive approach, the project aims to address the powerful gender norms and social influences identified in the formative research by engaging and empowering adolescents as researchers, educators, and champions for change. Vitu Newala also established youth centres as dedicated spaces to provide male and female youth with a safe environment for discussing and obtaining information on issues that affect sexual health and well-being. These centres are used as the hub of community-based activities, including educational sessions, drama and musical presentations, and planning workshops. These safe zones also serve as meeting spaces for Peer Facilitators and Guardians. Preliminary assessment of the pilot project indicated that, after six months of implementation, girls in the Vitu Newala communities felt a higher degree of concern and support for their safety and that boys, including Peer Facilitators and participants in the community-based events, were beginning to have more respectful and equitable attitudes toward their female peers. Based on these results, our hope is that Vitu Newala will be expanded to other neighbouring communities using the same participatory methods.

Acknowledgements

This research was made possible with the support of ViiV Healthcare's Positive Action programme. Some of the findings and details of the participatory methods utilized were included in ICRW and TAMASHA project reports and are available at: http://www.icrw.org/files/publications/Meet-Them-Where-They-Are-Participatory-Action-Research-Adolescent-Girls.pdf. The authors would like to thank Ms Anjala Kanesathasan and Dr Kirsten Stoebenau for their comments on this manuscript.

References

- EJ Kongnyuy, G Mlava, NR van den Broek. Facility-based maternal death review in three districts in the central region of Malawi: an analysis of causes and characteristics of maternal deaths. Women's Health Issues. 19(1): 2009; 14–20.

- N Daulaire, P Leidl, L Mackin. Promises to keep: the toll of unintended pregnancies on women's lives in the developing world. 2002; Global Health Council: Washington, DC.

- M Magadi, AO Agwanda. Determinants of transitions for first sexual intercourse, marriage and pregnancy among female adolescents: evidence from south Nyanza, Kenya. Journal of Biosocial Medicine. 41(3): 2009; 409–427.

- R Jewkes, R Morrell, N Christofides. Empowering teenagers to prevent pregnancy: lessons from South Africa. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 1(7): 2009; 675–688.

- MJ Hindin. The influence of women's early childbearing on subsequent empowerment in sub-Saharan Africa: a cross national meta-analysis. 2012; ICRW: Washington, DC.

- National Bureau of Statistics Tanzania Macro ICF. Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey, 2010. 2011; National Bureau of Statistics, ICF Macro: Dar es Salaam; Calverton, MD.

- S Singh. Abortion Worldwide: A Decade of Uneven Progress. 2009; Guttmacher Institute: New York.

- AE Biddlecom, L Hessburg, S Singh. Protecting the next generation in sub-Saharan Africa: learning from adolescents to prevent HIV and unintended pregnancy. 2007; Guttmacher Institute: New York.

- JA Fleischman. Suffering in silence: human rights abuses and HIV transmission to girls in Zambia. 2003; Human Rights Watch: New York.

- JR Glynn, M Carael, B Auvert. Why do young women have a much higher prevalence of HIV than young men?. AIDS. 15(Suppl.4): 2001; S51–S60.

- C Underwood, J Skinner, N Osman. Structural determinants of adolescent girls' vulnerability to HIV: views from community members in Botswana, Malawi, and Mozambique. Social Science & Medicine. 73(2): 2011; 343–350.

- World Health Organization. WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence against women: summary report of initial results on prevalence, health outcomes and women's responses. 2005; WHO: Geneva.

- MO Zakayo, J Lwelamira. Sexual behaviours among adolescents in community secondary schools in rural areas of central Tanzania: a case of Bahi District in Dodoma Region. Age. 14(3): 2011; 1–5.

- N Luke. Age and economic asymmetries in the sexual relationships of adolescent girls in sub-Saharan Africa. Studies in Family Planning. 34(2): 2003; 67–86.

- J Wamoyi, D Wight, M Plummer. Transactional sex amongst young people in rural northern Tanzania: an ethnography of young women's motivations and negotiation. Reproductive Health. 7(1): 2010; 2.

- J Wamoyi, A Fenwick, M Urassa. Women's bodies are shops: beliefs about transactional sex and implications for understanding gender power and HIV prevention in Tanzania. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 40(1): 2011; 5–15.

- LA McCloskey, C Williams, U Larsen. Gender inequality and intimate partner violence among women in Moshi, Tanzania. International Family Planning Perspectives. 31(3): 2005; 124–130.

- M Sommer. The changing nature of girlhood in Tanzania: influences from global imagery and globalization. Girlhood Studies. 3(1): 2010; 116–136.

- RO Levine, CB Lloyd, ME Greene. Girls count: a global investment and action agenda. 2008; Center for Global Development: Washington DC.

- M Temin, R Levine. Start with a girl. A new agenda for global health. 2009; Center for Global Development.

- H Coupland, L Maher, J Enriquez. Clients or colleagues? Reflections on the process of participatory action research with young injecting drug users. International Journal of Drug Policy. 16(3): 2005; 191–198.

- R Mabala. From HIV prevention to HIV protection: addressing the vulnerability of girls and young women in urban areas. Environment and Urbanization. 18(2): 2006; 407–432.