Abstract

Some of the commitments nations have made in international agreements, notably in the ICPD Programme of Action (1994) and the resolution of the UN Committee on Population & Development (2012), to young people include: realisation of the right to education and attainment of a secondary school education; delaying marriage beyond childhood and ensuring free and full choice in marriage-related decisions; exercise of the right to health, including access to friendly health services and counselling; access to health-promoting information, including on sexual and reproductive matters; acquisition of protective assets and agency, particularly among girls and young women, and promotion of gender equitable roles and attitudes; protection from gender-based violence; and socialisation in a supportive environment. These are crucial for a successful transition to adulthood with reference to sexual and reproductive health outcomes. This paper assesses the extent to which these commitments have been realised, drawing from available studies conducted in the 2000s in developing countries. It concludes that while some progress has been made in most of these aspects, developing countries have a long way to go before they can be said to be helping their young people achieve a successful sexual and reproductive health-related transition to adulthood.

Résumé

Certains engagements souscrits par les nations au titre d'accords internationaux, notamment le Programme d'action de la CIPD (1994) et la résolution de la Commission de la population et du développement (2012), prévoient : la réalisation du droit à l'éducation et l'accès à l'enseignement secondaire ; le retard du mariage après l'enfance et la garantie du libre choix dans les décisions relatives au mariage ; l'exercice du droit à la santé, notamment l'accès à des services et conseils de santé conviviaux ; l'accès à des informations sur la promotion de la santé, entre autres sur les questions sexuelles et génésiques ; l'acquisition d'articles de protection, particulièrement pour les filles et les jeunes femmes, et la promotion de rôles et d'attitudes basés sur l'égalité entre les sexes ; la protection contre la violence sexiste ; et la socialisation dans un environnement propice. Ces objectifs sont essentiels pour une transition réussie vers l'âge adulte du point de vue de l'état de santé sexuelle et génésique. L'article évalue dans quelle mesure ces engagements ont été réalisés, au moyen des études menées à compter de 2000 dans les pays en développement. Si certains progrès ont été accomplis dans la plupart de ces aspects, les pays en développement sont encore loin de pouvoir affirmer qu'ils aident leurs jeunes à négocier avec succès la transition vers l'âge adulte dans le domaine de la santé sexuelle et génésique.

Resumen

Algunos de los compromisos adquiridos por las naciones en acuerdos internacionales, principalmente en el Programa de Acción de CIPD (1994) y en la resolución del Comité de Población y Desarrollo de las Naciones Unidas (2012), son: realización del derecho a la educación y logro de educación secundaria; aplazamiento del matrimonio más allá de la infancia y garantía de decisiones libres y toda la gama de opciones en asuntos relacionados con el matrimonio; ejercicio del derecho a la salud, incluido el acceso a consejería y servicios de salud amigables; acceso a información que promueva salud, incluida la salud sexual y reproductiva; adquisición de medios para protegerse y capacidad para tomar decisiones, particularmente entre niñas y mujeres jóvenes; promoción de actitudes y roles de género equitativos; protección contra la violencia de género; y socialización en un ambiente de apoyo. Estos son fundamentales para lograr la transición a la adultez con relación a los resultados de salud sexual y reproductiva. En este artículo, basado en estudios realizados en la década de los 2000 en países en desarrollo, se evalúa hasta qué punto se han realizado estos compromisos. Se concluye que, aunque se han logrado algunos avances en la mayoría de estos aspectos, los países en desarrollo tienen un largo trecho por delante antes de que se pueda decir que están ayudando a la juventud a lograr la transición a la adultez con relación a la salud sexual y reproductiva.

In 1994, when the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) took place, it changed the world's population and development-related priorities, and emphasised social inclusion, human rights and the importance of addressing the needs and developing the capacities of the young. Today, the world has a larger population of young people aged 10–24 than ever before in history; there are an estimated 1.8 billion of them globally and they represent 26% of the world's population.Citation1 The importance of this population for the future of nations is well-recognised. Much has been said about the demographic dividend, and the power of young populations to contribute to development. Global commitments to ensuring a successful transition to adulthood have been articulated in international agreements, including the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (1979),Citation2 the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989),Citation3 the ICPD Programme of Action (1994),Citation4 the Millennium Development Goals,Citation5 and most recently, the resolution of the 45th Session of the United Nations Commission on Population and Development (UNCPD) (2012),Citation6 and the Bali Global Youth Forum Declaration (2012).Citation7

A synthesis of the commitments that nations have made in international agreements and conventions, as well as the available evidence,Citation8 suggests that a successful transition to adulthood with reference to sexual and reproductive health outcomes has seven attributes: realisation of the right to education and attainment of at least a secondary school education; delaying marriage beyond childhood and free and full choice in the timing of marriage and selection of partner; exercise of the right to health, including access to friendly and sensitive health services and counselling; access to health-promoting information including on sexual and reproductive matters; acquisition of protective assets and agency, particularly among girls and young women, and promotion of gender equitable roles and attitudes; protection from gender-based violence; and socialisation in a supportive environment.

The objective of this paper is to assess the extent to which these commitments have been realised. It notes the commitments made, specifically in the ICPD Programme of ActionCitation4 as compared to the actual situation, drawn from available published and unpublished, qualitative and quantitative studies conducted in the 2000s addressing young people's sexual and reproductive health and development in developing countries of Asia (largely southern Asia), Africa (including sub-Saharan and northern Africa) and Latin America. Where data are available, we also include evidence from Eastern and Southern Europe. Attempts were made to conduct an extensive search of available evidence in English over this period that related to the situation with regard to each of the seven attributes listed above among young people, including those defined as adolescents (aged 10–19) and those defined as youth (aged 15–24) more specifically, and interventions implemented to address the needs of the young. We attempted, moreover, to spread a wide geographical net, using Googlescholar and Popline, as well as documents prepared by various agencies, including the World Health Organization, United Nations Population Fund, United Nations Children's Fund, and Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS and the references cited in these documents, and a perusal of key journals with articles focused on the situation of the young. We have also used data from Demographic and Health Surveys from various countries obtained through the STATcompiler, an online data base tool. We note that available evidence focuses disproportionately on youth aged 15–24, and that those aged 10–14 are under-represented. Unfortunately, comparable data are not always available across regions and countries, necessitating, in many instances, the use of data from selected countries or regions only, or the use of multiple indicators reflecting different dimensions of each attribute for different regions.

Right to education at least through secondary school

The ICPD called for secondary education for young people, especially girls: “Beyond the achievement of the goal of universal primary education in all countries before the year 2015, all countries are urged to ensure the widest and earliest possible access by girls and women to secondary and higher levels of education.” (Para 4.18). Other paragraphs call for the elimination of gender disparities in access to, retention in, and support for education (Paras 6.7c; 11.5). Similar commitments were reiterated by the UNCPD (Para 21).

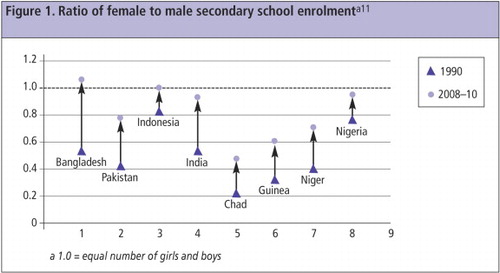

As regards universal primary education, as of 2009 only 87% of children in developing countries had completed primary school, and being poor and female were among the most pervasive factors keeping children out of primary school.Citation9 The transition to secondary school eludes many more: net enrolment ratios in 2007–2010 ranged from 55% for girls to 65% for boys.Citation10 And while the ratio of girls to boys in secondary school has improved in many settings, including in the eight countries in Asia and Africa presented below (

), it remains below one in many countries.Citation11 As a result, globally, about one-third of youth aged 15–24 have not completed a secondary education.Citation12A number of interventions have been implemented to promote adolescent girls' education. One review of such interventions found that although a wide variety of strategies have been tried, certain approaches predominated. These fall into three categories: making formal schools more accessible to girls by lowering or eliminating financial barriers through stipends, scholarships, or other forms of subsidy; mobilizing at the community level to advocate for girls' schooling in order to address cultural and social barriers; and providing non-formal educational alternatives to out-of-school girls.Citation13 Very few girl-friendly education programmes have been evaluated, and even fewer have made their evaluation reports publicly accessible. Thus, most approaches remain promising but unproven. This assessmentCitation13 argues that the supply of places in formal secondary schools needs to be significantly expanded; cash or in-kind resources should be carefully targeted to support girls who would not otherwise be able to stay in school; and non-formal education for girls should focus on complementary approaches that offer younger adolescents the opportunity to re-enter the formal educational system.

Eliminating child marriage and ensuring choice in marriage-related decisions

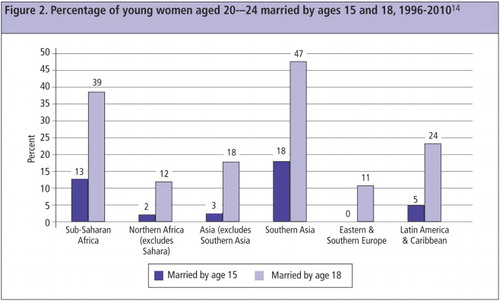

The ICPD recommended that governments “strictly enforce laws to ensure that marriage is entered into only with the free and full consent of the intending spouses... and laws concerning the minimum legal age of consent and the minimum age at marriage and should raise the minimum age at marriage where necessary (Paras 4.21, 5.5, 6.11). Similar recommendations were reiterated by the UNCPD (Para 9). We note that child marriage, as suggested in the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), refers to marriages of those who have not attained their majority, that is, age 18 (unless, under the applicable law, majority is attained earlier). The world has made slow progress in achieving this goal, and regional variation is wide. Among developing countries (excluding China), 35% of young women aged 20–24 marry below age 18, and 12% below age 15.Citation10 Child marriage is most prevalent in southern Asia (

), where almost half of all young women marry before age 18, and almost one-fifth before age 15. In sub-Saharan Africa, the situation is slightly better; and while child marriage is rarer in northern Africa, South East Asia, Oceania, and Latin America and the Caribbean, it has not been eliminated.Citation14 The trend from the early 1990s to the late-2000s is that less than 1% decline in child marriage has been achieved per year. The percentage of girls married by age 18 will fall, at best, to 40% in southern Asia and 30% in sub-Saharan Africa over the next five years if this trend is not improved.Child marriage goes hand in hand with young people's exclusion from the decision on when and whom to marry.Citation15,16

“I wanted to get an education but my parents were determined to marry me off....I tried to run away but my mother said she would kill herself if I did not marry him.”(Ethiopia, married age 13) Citation15

“What is there to ask them? We don't ask anyone. She knew only when the garland was put around her neck that she was getting married.”(India, mother of a married girl aged 16) Citation16

The right to health, including sexual and reproductive health, and youth-friendly services

ICPD supports young people's right to health: promoting “to the fullest extent the health, well-being and potential of all children, adolescents and youth” (Para 6.7(a)); meeting “special needs…for health, counselling and high-quality reproductive health services (Para 6.7(b)); and ensuring that programmes and attitudes of health care providers do not restrict the access of adolescents to appropriate services..... [T]hese services must safeguard the rights of adolescents to privacy, confidentiality, respect and informed consent (Para 7.45). The UNCPD also called for “special attention to promotion of sexual and reproductive health, and mental health; and… measures to prevent sexually transmitted diseases…” (Para 23).

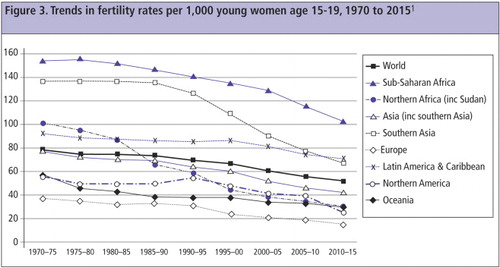

Although young people are healthier today than in previous generations, there remain several conditions that inflict a high burden of disease among them. Key among these are sexual and reproductive risk and ill-health. In many settings, children are bearing children – 20% of young women aged 20–24 in developing countries (excluding China) and 28% in countries of sub-Saharan Africa had initiated childbearing before they were aged 18.Citation10 Early childbearing is accompanied by rapid childbearing: at ages 15–24, 17% of married young women in sub-Saharan Africa, 13% in southern Asia, and 10% in Latin America and the Caribbean had already had three or more children.Citation14 While age-specific fertility rates among girls aged 15–19 have been declining, decline has been slow (

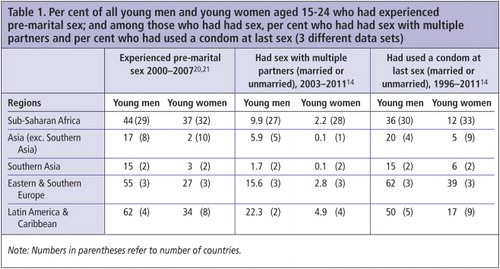

). Rates remain much higher in sub-Saharan Africa and just a little lower in southern Asia in 2013 than in the world in 1970–75.Citation1 Early motherhood can severely compromise the life options and health of young women, and have a long-term, adverse impact on their own and their children's quality of life.Early and unprotected sex characterises sexual relations among the young. Aside from early marriage and early initiation into sexual life within marriage, early sexual initiation before marriage is also observed. Overall, of young men aged 15–24, percentages reporting the experience of pre-marital sex ranged from 15% in Southern Asia to 62% in Latin America and the Caribbean, and for young women from 2–3% in Asia (including Southern Asia) to 37% in sub-Saharan Africa (Table 1

Table 1 Citation20

Among young women, moreover, sexual relations were non-consensual for significant minorities; indeed, a review of available evidence found that while non-consensual sexual relations, that is, sexual relations obtained through physical force, threats, deception, blackmail, or by drugging an unwilling victim, are experienced by young women in a host of settings, wide variations are observed in the proportions reporting such experiences, ranging from under 5% to over 20%.Citation22

Access to reproductive health services – mainly pregnancy-related, contraception, abortion, and treatment of infections – is limited for the young. For example, just 55% of young women who gave birth in adolescence in developing countries (excluding China), 48% in sub-Saharan Africa and 44% in Southern Asia reported skilled attendance at delivery.Citation10 Although the first pregnancy among young women is the riskiest, there is no evidence that adolescents were more likely to receive skilled attention than older women with higher order pregnancies.

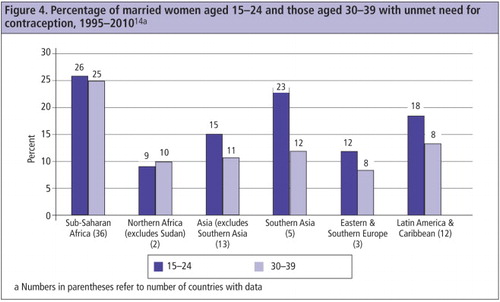

Unmet need for contraception remains high among married young women aged 15–24.Citation14

shows how much contraceptive services have failed young married women compared to those aged 30–39. Moreover, in 41 countries for which data are available for at least two points in time (before 2000, 2001–2005 and 2006 onwards), percentages of young women reporting an unmet need for contraception have fallen only modestly, from 27% to 21% over a 15-year period. In the most recent period covered, one-quarter of young women in sub-Saharan Africa reported an unmet need for contraception, over one-fifth in Southern Asia and Latin America & Caribbean, and about one-sixth in the rest of Asia.Citation14Unmarried young people face considerable obstacles in acquiring condoms or contraceptive supplies. Key reasons are that they are too poorly informed about where to obtain them or how to use them, and are embarrassed to ask in a shop or a health facility. “They ask too many questions.” Citation23 They also believe providers will reveal their secrets to others,Citation24 and are judgemental and unfriendly. In some cases unmarried youth are excluded in practice from services, irrespective of policy.Citation21,25

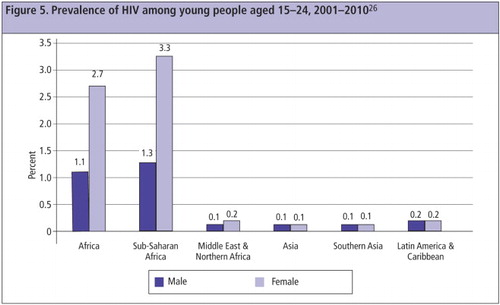

Thus, unprotected sex is common. Globally, an estimated 3.2 million young women and 1.7 million young men aged 15–24 were living with HIV in 2009, with prevalence the highest in Africa (

).Citation12,26 The gender disparity arises from the fact that young women tend to engage in relationships with men older than themselves, who have had more partners and more time to become infected, and therefore infect more young women.Citation14,27 While global estimates of STI prevalence disaggregated by age are not available, estimated global incidence among adults was 448.3 million cases in 2005 for chlamydia, gonorrhoea, syphilis and trichimonas vaginalis. This had risen to 498.9 million in 2008, with the increase at least partially attributed to the increasing number of young people becoming sexually active each year.Citation28High rates of unintended pregnancy and abortion are also observed among the young. Each year, nearly 22 million women worldwide have unsafe abortions,Citation29 almost all in developing countries. It is estimated that 41% of these take place among those aged 15–24, while in Africa, about half occur among young women.Citation30 Many suffer negative health and social consequences, ranging from haemorrhage, sepsis and other life-threatening morbidities from unsafe abortion complications,Citation30 to social isolation, premature discontinuation of education and forced early marriage when giving birth at a young age.

Because of early initiation of childbearing, inadequate care during pregnancy and poor access to safe abortion, maternal mortality claims the lives of some 50,000 adolescents annually. Indeed, adolescents aged 15–19 contribute to 11% of all births and account for 14% of all maternal deaths globally.Citation31 The estimated risk of mortality is even higher among adolescents than those aged 20–24 (408 vs. 319 deaths per 100,000 live births).Citation32 Adolescents are also more likely than older women to bear underweight infants and experience more neonatal and infant deaths.

The need to overcome serious barriers to receiving health services is universally recognised, and several developing countries have aimed to do so and implemented interventions. A systematic review of evidence from 16 country-level evaluations (12 in Africa, 3 in Asia, 1 in Latin America) has highlighted the effectiveness of interventions that have focused on three components. First, service providers were trained and oriented about young people's needs, communicating with and counselling the young, and providing services in non-threatening ways. Second, facilities were youth-friendly, of good quality, acceptable and equipped to provide confidential services, often at subsidised rates. Third, activities were implemented to generate demand and support for services at community level, and raise awareness among the young about the availability of youth-friendly services.Citation33 At the same time, a host of related actions were found to be important, including the provision of accurate information, easy access to contraceptive supplies, home visits to reach the most vulnerable, creation of supportive social norms, building life skills, and engaging men and boys.Citation34 Thus far, however, programmes and services for the young in most countries have failed to meet these conditions.

Provision of education about sexuality and reproduction

Many countries have made many commitments to ensure that all adolescent boys and girls have age-appropriate sexual and reproductive health information. The ICPD highlighted in at least seven paragraphs (7.8, 7.37, 7.41, 7.46, 8.24, 8.31, 11.9) the need for age-appropriate and sensitively delivered sexuality education programmes for the young. It recommended that “support should be given to integral sexual education and services for young people (Para 7.37); “information... should be made available to adolescents to help them understand their sexuality and protect them from unwanted pregnancies, [and] sexually transmitted diseases” (Para 7.41) and “to be most effective, education about population issues must begin in primary school” (Para 11.9).

Countries are far from achieving these goals. Although young people thirst for information, they remain misinformed, for example, about how pregnancy happens and how it can be prevented, or what happens in relationships and marriage, and much more. The information provided to them, moreover, tends to be delivered in judgemental ways that do not respect their rights, is often gender insensitive and not always evidence-based. In developing countries, comprehensive knowledge about HIV (defined as knowing two ways to prevent HIV and rejecting three misconceptions) is limited, reported by only 24% of young women and 36% of young men aged 15–24, far below the global target of 95% by 2010. Regionally, awareness levels were lowest in Northern Africa (9% among young women and 17% among young men) and highest in Latin America & Caribbean, 44% and 48%, respectively.Citation26 Awareness about pregnancy and contraception is also limited – for example, in India, just two in five young men and women aged 15–24 knew that a woman can become pregnant the first time she has sex; just three in ten girls knew that a male condom can be used just once.Citation21

In spite of all the evidence sumarised here about the unmet need for information on sexual and reproductive matters, there continues to be a global debate about whether or not to provide sexuality education, and misconceptions abound about the goal and content of such education. The literature finds that the content of most sexuality education programmes is indeed age-appropriate. As regards effectiveness, the evidence is conclusive on two fronts: (a) abstinence-only programmes are ineffective and withholding information about contraceptives and condoms actually places young people at increased risk of unplanned pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections; and (b) broad-based programmes not only reduce misinformation but also increase young people's skills in making informed decisions, including delaying first sex, having few partners, and using contraception and/or condoms. Studies found that risky sexual behaviour was reduced by roughly 25–33%. Not a single study has found evidence that providing young people with sexuality education resulted in increased risk-taking.Citation35,36 At the same time, youth have reiterated their own preferences for education that makes them aware of their right to stay healthy, that is non-judgemental, rights-based, age-appropriate, gender sensitive, comprehensive and context-specific.Citation7 In short, there is both an evidence-based rationale and a call from young people themselves for promoting sexuality education, a need and right that continues to be denied across much of the world.

Agency, rights and gender equity

The ICPD argued strongly for special attention to the development of life skills among girls and countering prevailing gender roles and stereotypes, and recognised the links between young women's agency and their ability to claim their rights. It argued for the establishment of “appropriate programmes... for the education and counselling of adolescents in the areas of gender relations and equality, violence against adolescents, responsible sexual behaviour, responsible family planning practice, family life.... Such programmes should.... make a conscious effort to strengthen positive social and cultural values” (Para 7.47). It advocated for changing norms of masculinity, calling for “education of young men to respect women's self-determination and to share responsibility with women in matters of sexuality and reproduction” (Para 7.41).

The reality in many developing countries is otherwise, with persisting gender role disparities and limited social capital among young women. Compared to adolescent boys, adolescent girls' networks of friends are limited: for example, boys in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, reported an average of five friends compared to three among girls; in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, 76% of boys compared to 48% of girls reported having many friends; in India, twice as many boys as girls had five or more friends with whom they could discuss personal matters.Citation37,21 In many settings, few girls have access to safe and social spaces outside their homes and schools in which they can make and meet friends and strengthen peer support networks. In the slums of Nairobi, for example, two-thirds of boys, compared with only one-third of girls, reported having a safe place to meet same-sex friends.Citation37 In rural Upper Egypt, the only non-familial social outlet girls had was the school.Citation37 In rural India, likewise, girls rarely met their friends outside of their home or school; boys, in contrast, reported ample opportunities to socialise with their peers.Citation23

Likewise, girls and young women in several regions are denied agency in managing their own lives. For example, just 11% of married young women aged 15–24 in sub-Saharan Africa, 35% in Southern Asia, and no more than half in the rest of Asia displayed decision-making autonomy in seeking health care, making major household purchases, purchasing daily household items, or visiting family or relatives.Citation14 Many girls in many countries do not have the negotiation power to refuse unwanted or unsafe sexual advances,Citation22 and many display limited self-esteem and the confidence to be able to speak up or confront someone with whom they disagree.

Unequal gender norms in relation to education are recognized and expressed even among very young adolescents. As a 12-year-old girl in Guatemala noted: “They say that only boys should [study], because they're more intelligent. Some people tell my father: ‘Don't support her studies because you'll only waste your money and she'll get married and won't finish school.’” Citation37 And a ten-year-old boy from rural India believed: “It is more important for boys to complete their education than girls because boys have to do a job and girls don't.” Citation23

A review of evidence-based approaches to protecting adolescent girls from sexual riskCitation38 has identified a number of core programme attributes, including a safe social space apart from home and school, a friendship network, mentors and role models, life skills education, agency-building activities, information about services and health, social, and economic rights, financial literacy and savings, self-protection plans and knowledge of what community resources exist to access when needed. Girls participating in programmes with these elements in South Africa were more likely than those in comparison groups to have a savings plan, display self-esteem, have confidence in their ability to obtain a condom, and report social inclusion in their community.Citation37 Likewise, a programme for girls in Ethiopia noted improvements in friendship networks, school attendance, age at marriage, reproductive health knowledge and communication, and contraceptive use.Citation39 Programmes among boys and young men have demonstrated success, moreover, in enabling participants to adopt gender egalitarian norms of masculinity and femininity, and at the same time reduced the experience of symptoms suggestive of sexually transmitted infections.Citation40

Protection from gender-based violence

The ICPD committed countries to protecting young people, especially young women, from violence, calling on governments to “take effective steps to address... abuse of children, adolescents and youth” (Para 6.9). The UNCPD resolution, likewise, urges the enactment and enforcement of legislation to “protect all adolescents and youth... from all forms of violence, including gender-based violence and sexual violence... and to provide social and health services, including sexual and reproductive health services, and complaint and reporting mechanisms for the redress of violations of their human rights.” (Para 12).

Evidence suggests that violence against the young takes many forms. Many grow up witnessing their father beating their mother, many have themselves been the victims of parental violence – key determinants of perpetration of and submission to violence in intimate relationships in adulthood.Citation41 Gender-based violence against young women is perpetrated largely by husbands and partners; for example, more than half of married young women aged 15–24 in Uganda, and between one-third and half in Zimbabwe, Tanzania, India and Bangladesh have reported ever having experienced marital violence.Citation42–46

Sexually experienced unmarried young women also report forced sexual encounters. Analysis of DHS data found that the first sexual experience was non-consensual for between 2% of young women in Azerbaijan and 64% in the Democratic Republic of Congo.Citation47 Studies in Ghana, Malawi, Uganda and India found that for almost one-fifth of sexually experienced girls aged 15–19, the first sexual experience was forced or at their partner's insistence.Citation24,48 Typical responses were:

“After he forced me [to have sex], he started sending my friend, a girl, [to talk to me]... My friend convinced me that such things happen to every girl, so I should get used [to it]. So I forgave the boy and went back to him.” (Uganda, aged 15)Citation24

“I went there. He was alone. He locked the door; he threatened me saying how could he marry me if I behaved like this. He beat me when I tried to get out.” (India, aged 19)Citation48

Ensuring young people's “right to be cared for, guided and supported”

Recognising gatekeeper inhibitions, the ICPD called for programmes that sensitise those “in a position to provide guidance to adolescents concerning responsible sexual and reproductive behaviour, particularly parents and families, and also communities, religious institutions, schools, the mass media and peer groups (Para 7.48). It highlighted the need to promote parent-child interaction, calling for “the education of parents, with the objective of improving the interaction of parents and children to enable parents to comply better with their educational duties to support the process of maturation of their children, particularly in the areas of sexual behaviour and reproductive health” (Para 7.48).

In many countries, the environment is far from nurturing of young people's needs, and neither parent-child relationships nor relationships between adolescents and their teachers or other potential adult mentors are characterised by respect and communication.Citation53 Available evidence suggests that parents rarely provide children information or guidance on sexual and reproductive matters. In Burkina Faso, for example, fewer than two-fifths of girls and one-tenth of boys had discussed these matters with a parent.Citation24 In India, fewer than 1% of youth had discussed reproductive processes with a parent.Citation21 Boys in a focus group discussion in Ghana said: “Some people ask their peers about sex because when they ask their parents, they might think [children] want to do such things. Parents think they are naughty, so they turn to their peers.” A mother in Burkina Faso said: “The children are afraid to talk to me about these topics.” Citation24 A mother in India said: “ One should not tell one's children about all these things; one should let them learn about these things after they get married.” Citation54 Embarrassment, traditional norms, misperceptions that talking about these matters will encourage sexual activity, and limited communication skills inhibit adults from providing the young a supportive environment.

Interventions that address parents are scarce. However, given the key role parents play and given evidence that young people wish to engage with their parents on issues of sexual and reproductive health, what is needed are activities that support parents with information, skills and resources, notably about normal adolescent development, sex, substance use, communication skills, and information about local resources.Citation53 Efforts to create and test appropriate interventions in different cultural contexts are badly needed.

Moving forward

While progress in meeting commitments to young people has been slow, there are encouraging signs. For one, there is far more policy and programme commitment to investing in young people than in 1994. Many countries have recognised the importance of improving sexual and reproductive health and choice among young people, and the links between youth development and the future of nations. The 45th session of the UN Commission on Population and Development in 2012 reconfirmed the global commitments made in the ICPD, and refocused the global agenda on young people's sexual and reproductive health. Second, the current generation of young people are certainly healthier, better educated, more exposed to new ideas, better aware of rights and better equipped to enter a rapidly globalising world than earlier ones. Third, precedents exist that have shown promise for empowering adolescents, building gender equity, and removing obstacles to health promotion, health and health seeking. Finally, and perhaps most significantly, young people are empowering themselves and youth leaders are playing a key role in determining the global agenda for youth. At the ICPD+15 Global Youth Forum in Bali in 2012, youth reaffirmed this agenda, focused on sexual and reproductive rights and inclusion of the most marginalised. The Bali Global Youth Forum Declaration placed young people and their rights at the core of development, and reinforced the attributes of a successful transition to adulthood discussed in this paper. It demanded, moreover, sustained and meaningful youth participation in the formulation and implementation of rights-based policies and programmes.Citation7

The ICPD Programme of Action's goals for youth remain as valid a roadmap in 2013 as they were in 1994. Meeting these commitments calls for the conviction that investing in young people is key to world development and a belief that it is the right thing to do.

Acknowledgements

This paper is an adapted version of a presentation made to the 45th Session of the UN Commission on Population and Development, New York, 2012. We gratefully acknowledge inputs and support from many. Rajib Acharya, Ann Biddlecom, Ann Blanc, Judith Bruce, Diane Rubino, Cheryl Sawyer and Iqbal Shah made insightful comments on earlier versions. MA Jose, Komal Saxena and Shilpi Rampal provided huge research support. Support from the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, John D and Catherine T MacArthur Foundation, Ford Foundation, Richard and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Elton John AIDS Foundation and the UK Government Department for International Development to the Population Council is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division. World Population Prospects: the 2010 revision, 2012. http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/index.htm

- United Nations. Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination Against Women. 1979; UN: New York. (http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/cedaw/text/econvention.htm#intro

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of the Child. 1989; UN: New York.

- United Nations. International Conference on Population and Development Programme of Action. 1994; UN.

- United Nations. Millennium Development Goals. 2000; UN: New York. http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/mdgoverview.html

- United Nations. Official Records of the Economic and Social Council, 2012, Supplement No. 5 (E/2012/25). 2012; UN: New York.

- United Nations Population Fund. Bali Global Youth Forum Declaration. 2012; UNFPA: New York.

- National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. Growing Up Global: The changing transitions to adulthood in developing countries. 2005; National Academies Press: Washington, DC.

- United Nations. The Millennium Development Goals Report 2011. 2011; UN: New York.

- United Nations Children's Fund. Progress for Children: A report card on adolescents. 2012; UNICEF: New York.

- United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation Institute for Statistics. http://stats.uis.unesco.org.

- United Nations Children's Fund. The State of the World's Children 2011. Adolescence: an age of opportunity. 2011; UNICEF: New York.

- CB Lloyd, J Young. New lessons: the power of educating adolescent girls. 2009; Population Council: New York.

- ICF International. Measure DHS STATcompiler, 2012. http://statcompiler.com

- W Ross. Ethiopian girls fight child marriages. 2011; Amhara: BBC News. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-13681053

- KG Santhya, N Haberland, AK Singh. She knew only when the garland was put around her neck: findings from an exploratory study on early marriage in Rajasthan. 2006; Population Council: New Delhi.

- A Malhotra, A Warner, A McGongle. Solutions to end child marriage: what the evidence shows. 2011; International Centre for Research on Women: Washington, DC.

- S Lee-Rife, A Malhotra, A Warner. What works to prevent child marriage: a review of the evidence. Studies in Family Planning. 43(4): 2012; 287–303.

- J Cleland, MM Ali, I Shah. Trends in protective behaviour among single vs. married young women in sub-Saharan Africa: the big picture. Reproductive Health Matters. 14(28): 2006; 17–22.

- ICF International. The HIV/AIDS data compiler: HIV/AIDS survey indicators data base. http://hivdata.measuredhs.com/start.cfm

- International Institute for Population Sciences and Population Council. Youth in India: Situation and Needs 2006–2007. 2010; IIPS: Mumbai.

- Jejeebhoy SJ, Bott S. Non-consensual sexual experiences of young people in developing countries: an overview. In: Jejeebhoy SJ, Shah I, Thapa S. Non-consensual sex and young people: looking ahead. In: Sex without Consent: Young People in Developing Countries. Jejeebhoy SJ, Shah I, Thapa S, editors. London: Zed Books, 2005. p.341–53.

- KG Santhya, SJ Jejeebhoy, I Saeed. Growing up in rural India: an exploration into the lives of younger and older adolescents in Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh. 2013; Population Council: New Delhi.

- AE Biddlecom, L Hessburg, S Singh. Protecting the next generation in sub-Saharan Africa: learning from adolescents to prevent HIV and unintended pregnancy. 2007; Guttmacher Institute: New York.

- A Tylee, DM Haller, T Graham, R Churchill, LA Sanci. Youth-friendly primary-care services: how are we doing and what more needs to be done. Lancet. 2007DOI-10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60371-7.

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Securing the future today: synthesis of strategic information on HIV and young people. 2011; UNAIDS: Geneva.

- J Bruce, S Clark. The implications of early marriage for HIV/AIDS policy. 2004; Population Council: New York.

- World Health Organization. Global incidence and prevalence of selected curable sexually transmitted infections – 2008. 2008; WHO: Geneva.

- World Health Organization. Unsafe abortion: global and regional estimates of the incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2008. 6th ed. 2001; WHO: Geneva. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/unsafe_abortion/9789241501118/en/index.html

- IH Shah, E Åhman. Unsafe abortion differentials in 2008 by age and developing country region: high burden among young women. Reproductive Health Matters. 20(39): 2012; 169–173.

- World Health Organization. Mortality estimates by cause, age and sex for the year 2008. 2001; WHO: Geneva.

- Blanc AK, Winfrey W, Ross J. New findings for maternal mortality age patterns: aggregated results for 38 countries, 2012. (Unpublished)

- B Dick, J Ferguson, C Chandra-Mouli. Review of the evidence for interventions to increase young people's use of health services in developing countries. DA Ross, B Dick, J Ferguson. Preventing HIV/AIDS in young people: a systematic review of the evidence from developing countries. 2006; WHO: Geneva.

- World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines on preventing early pregnancy and poor reproductive outcomes among adolescents in developing countries. 2001; WHO: Geneva.

- HD Boonstra. Advancing sexuality education in developing countries: evidence and implications. Guttmacher Policy Review. 14(3): 2011

- D Kirby. The impact of abstinence and comprehensive sex and STD/HIV education programmes on adolescent sexual behaviour. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. 5(3): 2008; 18–27.

- K Hallman, E Roca. Reducing the social exclusion of girls. Promoting healthy, safe and productive transitions to adulthood. Brief No.27. 2007; Population Council: New York.

- J Bruce, M Temin, K Hallman. Evidence-based approaches to protecting adolescent girls at risk of HIV. AIDSTAR-One Spotlight on Gender. 2012

- AS Erulkar, E Muthengi. Evaluation of Berhane Hewan: a program to delay child marriage in rural Ethiopia. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 35(1): 2009; 6–14.

- J Pulerwitz, G Barker, M Segundo. Promoting more gender-equitable norms and behaviors among young men as an HIV/AIDS prevention strategy. Horizons Final Report. 2006; Population Council: Washington, DC.

- DM Capaldi, NM Knoble, JW Shortt. A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse. 3(2): 2012; 231–280.

- Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) Macro International Inc. Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2006. 2007; UBOS and Macro International: Calverton, MD.

- Central Statistical Office Zimbabwe Macro International. Zimbabwe Demographic and Health Survey 2005–06. 2007; CSO and Macro International: Calverton MD.

- National Bureau of Statistics Tanzania ICF Macro. Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey 2010. 2011; NBS and ICF Macro: Dar es Salaam.

- International Institute for Population Sciences and Macro International. National Family Health Survey 3, 2005–06: India: Vol 1. 2007; IIPS: Mumbai.

- National Institute of Population Research and Training Mitra and Associates Macro International. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2007. 2009; NIPRT, Mitra and Assoc, Macro International: Dhaka and Calverton, MD.

- SJ Jejeebhoy. Protecting young people from sex without consent. Promoting healthy, safe, and productive transitions to adulthood, Brief No.7. 2011; Population Council: New York.

- KG Santhya, R Acharya, SJ Jejeebhoy. Timing of first sex before marriage and its correlates: evidence from India. Culture, Health and Sexuality. 13(3): 2011; 327–341.

- AK Blanc, A Melnikas, M Chau. A review of the evidence on multi-sectoral interventions to reduce violence against adolescent girls. 2012; Population Council: New York.

- PM Pronyk, RH James, CK Julia. Effect of a structural intervention for the prevention of intimate-partner violence and HIV in rural South Africa: a cluster randomised trial. Lancet. 368(9551): 2006; 1973–1983.

- R Jewkes, M Nduna, J Levin. Impact of Stepping Stones on incidence of HIV and HSV-2 and sexual behaviour in rural South Africa: a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 337: 2008; a506.

- RK Verma, J Pulerwitz, VS Mahendra. Promoting gender equity as a strategy to reduce HIV risk and gender-based violence among young men in India. Horizons Final Report. 2008; Population Council: New York.

- World Health Organization. Helping parents in developing countries improve adolescents' health. 2007; WHO: Geneva.

- SJ Jejeebhoy, KG Santhya. Parent-child communication on sexual and reproductive health matters: perspectives of mothers and fathers of youth in India. 2011; Population Council: New Delhi.