Abstract

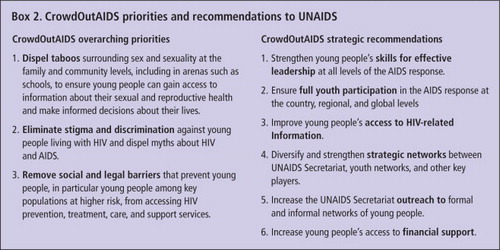

To develop a strategy for how to better engage young people in decision-making processes on AIDS, UNAIDS launched the participatory online policy project CrowdOutAIDS in 2011. A total of 3,497 young people aged 15–29 from 79 countries signed up to nine online forums, and volunteers recruited through the online platform hosted 39 community-based offline forums with an additional 1,605 participants. This article describes the participatory approach of using social media and crowdsourcing solutions to integrate youth perspectives into strategy and policy processes. In these forums, youth consistently identified the need to change the way sex and relationships are dealt with through changing how sex is talked about, putting comprehensive sexuality education in place, and overcoming social and cultural taboos. The outcome document recommended three major priorities: dispel taboos surrounding sex and sexuality, eliminate stigma and discrimination against young people living with HIV, and remove social and legal barriers. Six strategic actions were also recommended: strengthen young people's skills for effective leadership, ensure full youth participation in the AIDS response, increase access to HIV-related information, strengthen strategic networks, increase UNAIDS's outreach to young people, and increase young people's access to financial support. Through leveraging social media and crowdsourcing, it is possible to integrate grassroots perspectives from across the globe into a new model of engagement and participation, which should be further explored for community empowerment and mobilization.

Résumé

En 2011, l'ONUSIDA a lancé le projet participatif en ligne CrowdOutAIDS pour définir une stratégie associant davantage les jeunes à la prise de décision sur le sida. Au total, 3497 jeunes de 15 à 29 ans, venant de 79 pays, se sont inscrits dans neuf forums en ligne, et des bénévoles recrutés par la plateforme en ligne ont accueilli 39 forums communautaires hors ligne avec 1605 participants supplémentaires. L'article décrit l'approche participative de l'utilisation des médias sociaux et les solutions d'externalisation ouverte pour intégrer les perspectives des jeunes dans la définition de la stratégie et de la politique. Dans ces forums, les jeunes ont régulièrement noté qu'il fallait aborder différemment les relations sexuelles en changeant la manière dont on parle de la sexualité, en mettant en place l'éducation sexuelle et en surmontant les tabous sociaux et culturels. Le document final a souligné trois priorités : lever les tabous entourant la sexualité, éliminer la stigmatisation et la discrimination dont souffrent les jeunes vivant avec le VIH et supprimer les obstacles sociaux et juridiques. Six mesures stratégiques ont aussi été préconisées : renforcer les aptitudes des jeunes à un leadership utile, garantir leur pleine participation à la réponse au sida, élargir l'accès à l'information relative au VIH, resserrer les réseaux stratégiques, accroître le rayonnement de l'ONUSIDA auprès des jeunes et améliorer leur accès au soutien financier. Avec les médias sociaux et l'externalisation ouverte, il est possible d'intégrer des perspectives locales venant du monde entier dans un nouveau modèle d'engagement et de participation, qui devrait être mieux étudié pour l'autonomisation et la mobilisation communautaires.

Resumen

Con el fin de formular una estrategia sobre la mejor manera de fomentar la participación de las personas jóvenes en los procesos de toma de decisiones sobre el SIDA, ONUSIDA puso en marcha CrowdOutAIDS, un proyecto colaborativo online de políticas, en 2011. Un total de 3497 jóvenes de 15 a 29 años de edad, en 79 países, se inscribieron en nueve foros online y los voluntarios reclutados por medio de la plataforma online organizaron 39 foros comunitarios offline con 1605 participantes. En este artículo se describe el enfoque participativo de utilizar los medios sociales de comunicación y soluciones de crowdsourcing para integrar las perspectivas de la juventud en los procesos de estrategias y políticas. En esos foros, las personas jóvenes identificaron la necesidad de cambiar la manera en que se tratan el sexo y las relaciones al cambiar la manera en que se habla sobre sexo, ofreciendo educación sexual y superando los tabúes sociales y culturales. En el documento final se recomendaron tres prioridades: disipar los tabúes en torno al sexo y la sexualidad, eliminar el estigma y la discriminación contra las personas jóvenes que viven con VIH y eliminar las barreras sociales y jurídicas. Además, se recomendaron seis acciones estratégicas: fortalecer las habilidades de la juventud para un liderazgo eficiente, garantizar la participación total de la juventud en respuesta al SIDA, ampliar el acceso a la información relacionada con el VIH, fortalecer las redes estratégicas, aumentar el alcance de ONUSIDA a la juventud y ampliar el acceso de la juventud a ayuda financiera. Al aprovechar los medios sociales de comunicación y crowdsourcing, es posible integrar las perspectivas de las bases a nivel mundial en un nuevo modelo de colaboración y participación, el cual se debe explorar más a fondo para empoderar y movilizar a las comunidades.

In 2012, at the 45th meeting of the United Nations Commission on Population and Development (CPD), a historic resolution was adopted by UN Member States acknowledging that adolescents and young people have the right to control and decide freely and responsibly on matters related to their sexuality, including sexual and reproductive health, independently of their age and marital status.Citation1 The resolution also calls for providing young people with evidence-based, comprehensive education on sexuality, sexual and reproductive health, human rights and gender equality.Citation1 This is the first ever CPD resolution to address the human rights of adolescents and youth, including sexual and reproductive health and rights, providing a strong precedent and framework for action.

Yet this resolution was hard won and negotiations were particularly contentious when it came to language on “gender”, “sexual orientation”, “comprehensive sexuality education”, “sexual and reproductive health services”, and also the inclusion of language on “parental rights”, “responsible and/or moral behaviour” and “culture”. Given that the CPD negotiations took place just over a month after those at the Commission on the Status of Women (CSW), where Agreed Conclusions on the theme of rural women were ultimately not adopted due to the lack of consensus around a number of these same issues, the fact that a resolution was adopted at all can be seen as a breakthrough. Young people present at the negotiations stood for various points of the discussion,Citation2 portraying the diverging views that exist not only amongst Member States, but also young people themselves when it came to how they live and experience their sexuality.

The world currently hosts the largest generation of young people in history. This has spurred a growing focus on young people in policy-making. In conjunction, youth organizations have called for the fulfilment of the right of young people to participate in all aspects of decision-making that affect their lives. As UNAIDS and others have highlighted, the participation of young people is key to establishing successful HIV-related policies and programmes.Citation3,4 Participation ensures a greater sense of ownership of proposed solutions, enables young people to exercise their citizenship, promotes empowerment, and fosters a greater sense of control over their lives and futures.Citation5

In the Political Declaration on HIV/AIDS adopted at the UN General Assembly high level meeting on AIDS in June 2011, member states committed to harnessing the energy of young people in helping to lead global HIV awareness, as well as encouraging and supporting the active involvement and leadership of young people in the AIDS response. While the UNAIDS Secretariat had previously engaged in a number of efforts to support youth participation and leadership, a more strategic and coherent approach was deemed necessary to fulfil these commitments.Citation6

To develop an approach for how to better engage young people in country, regional and global decision-making processes on AIDS, and to seize the growing momentum for social change led by youth movements around the world, accelerated by new communication technology, the UNAIDS Secretariat launched a participatory online policy project called CrowdOutAIDS. It used social media and crowdsourcing,Citation7 an innovative approach to public participation, to enable young people to both formulate the problems as well as generate solutions to youth leadership and participation in the AIDS response.Footnote* This resulted in the first ever crowdsourced strategy document in the history of the UN.

This article describes the CrowdOutAIDS participatory process and presents a focused thematic analysis of a sub-section of the views expressed on the online platforms and in the related offline forums.

Background on crowdsourcing

The introduction of social media has changed the relationship between the source of a message and the audience, where the audience no longer passively consumes media content, but actively engages in creating it.Citation8 This marks a shift from a one-to-many to a many-to-many model of communication online,Citation8 which has implications for how young people access information about sex and sexuality as well as the type of information available. Ownership has moved from government-controlled public health agencies with state-sanctioned messages to multiple and diverse voices in the online environment, where the audience can now engage, reinterpret and generate sexual health information.

However, the potential of social media within the field of public health is not confined to providing health information and promotion. This new technology could also be used to enable direct public participation in shaping priorities for public policy and planning,Citation9 as well as shaping the legal environment,Citation10 to increase transparency of and trust in public institutions and processes.

Drawing upon these recent technological and social developments, as well as the fact that young people are generally early adopters in uptake of new technology and modes of communication, CrowdOutAIDS was conceived to leverage social media and crowdsourcing to enable young people to fully take part in shaping policy priorities and actions for the UNAIDS Secretariat.

CrowdOutAIDS: leveraging social media for full participation

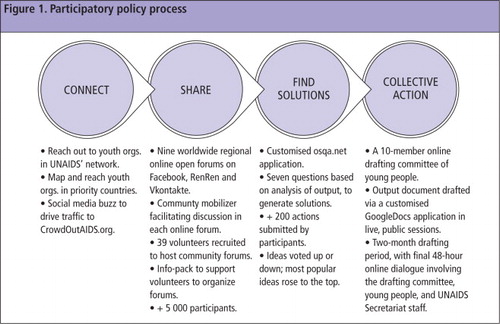

The “virtual” participatory policy process (

) was implemented via the online platform CrowdOutAIDS.org, and was conceptualized around four simple objectives: connecting a community of interested young people; creating a space where young people could share their experiences, ideas and information; synthesizing this crowd's knowledge and enabling them to find solutions; and lastly, collective action through co-authoring the final strategy document, and the establishment of a network of youth activists and organizations that the UNAIDS Secretariat could work with to implement the strategy.Methodology

The data for this article were drawn from a secondary analysis of the themes and texts that emerged during the CrowdOutAIDS process, from both online and offline discussions, which took place from October through December 2011.

Sample and data collection

We used a network approach to create the initial buzz through online social media, where we consciously targeted so-called nodes in the network, that is, young people connected to sexual health activism, and relied on them to spread the word in turn to family, friends and acquaintances online and offline. The discussions included 3,479 people aged 15–29 from nine online regional forums, representing 79 countries. The numbers of online participants by forum were: Africa English (570), Africa French (226), Latin America with a separate forum for Brazil (673), Asia Pacific (529), Eastern Europe & Central Asia (110), Middle East and North Africa (391), North America, Caribbean and Central Europe (796). Regions were selected based on the UNAIDS regions. In addition, China (228) was added to ensure that all languages spoken in the BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) were included. Participants were directed to any given forum based on both region and language of the country from which the participant accessed the platform. For example, a person from a predominantly English-speaking country in the Caribbean would be directed to the North America online forum, whereas a Spanish speaker would be directed to the Latin American online form.

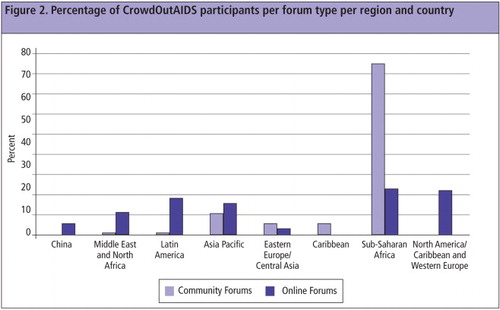

To overcome the “digital divide”, volunteers were recruited via a crowdmapping application on CrowdOutAIDS.org to host offline community-based open forums. Specific outreach was carried out to set up community forums in sub-Saharan Africa, as internet penetration there is still relatively low at 13.5% of the population, compared to the global average of 32.7%.Citation11 Thirty-nine offline community forums took place across the world with a total of 1,605 participants (

). The forums in each region, respectively, were held in the following countries: Latin America hosted by El Salvador, the Caribbean by Guyana (4); Asia Pacific had forums in Bangladesh, India (3), Malaysia, Nepal, Thailand; Africa had forums in Cameroon (2), Ethiopia (2), Kenya (5), Malawi, Nigeria (8), South Africa, Uganda (4), Zambia, and Zimbabwe. There were no offline meetings hosted in North America or Europe. About two-thirds of offline forums were held in sub-Saharan Africa with 76% of all participants, which was in line with the ambition to ensure community participation in countries and communities where internet penetration was lower. It is worth noting, however, that the sub-Saharan African online forums collectively had the same number of participants as the North America, Caribbean and Western Europe online forums.Offline community forum volunteers were provided with an Info-pack based on a structured participatory dialogue-for-action methodology. It included a how-to guide, a structured discussion guide, a reporting template for collecting qualitative data from the discussions and demographic data on participants, as well as a registration form to allow for follow-up with participants.

In the offline community open forums, 48% of participants were male and 52% female. Out of the 39 community forums hosted, key populations at higher risk were represented in the following number of forums: young people living with HIV (14), sex workers (3), men who have sex with men (4), and people who inject drugs (2). In addition, community forums included out-of-school young people (18), students (27), and peer educators (18). With regard to age, 12 forums had at least one person over the age of 30 present, and 10 forums had at least one person under the age of 15. The majority of the participants were aged 15–29, the target age group. Demographic data for online forum participants were not collected.

Questions asked and method of analysis

In order to show how the internet and social media are changing young people's opportunities to influence information, and their involvement in the creation of knowledge about sex and relationships, our focus here is twofold. We provide both a presentation of the analytic process used to feed youth voices into a larger strategy process, and an example of the actual content they created in response to a sub-set of the questions raised in the forums.

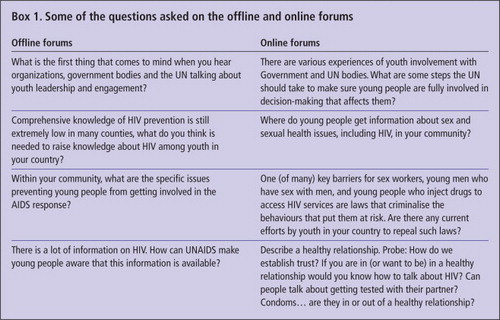

Twenty-six questions were asked on the online forums and 17 in the offline community forums (see Box 1

for examples). While the main aim was to generate information and perspectives on youth participation and leadership, substantive parts of the discussions covered themes related to young people and HIV, including young people living with HIV, access to services, and the legal and social environment, among others.In order to ensure transparency and integration of participant perspectives into the policy process, data from online and offline forums were analyzed using a rapid approach variation of qualitative thematic analysis.Citation12 The online community mobilizers, who were trained by a qualitative research expert, performed thematic analysis and wrote blog summaries on a weekly basis. The hosts of the offline meetings submitted discussion summaries. Offline forums were analyzed using collaborative analysis, text (words spoken and written by crowd participants) from the forums was independently read by four project members. Each member identified major themes within the text. Collaborative meetings were held with the core project team made up of UNAIDS staff and youth consultants, to present, compile and synthesize themes from offline and online forums. These themes were then used to create questions for the “Find Solutions” application implemented in the third phase. They were also used by the drafting committee in developing content for the final strategy document.

Participant quotes are presented below to reveal how youth talked and wrote about these issues. Quotes taken from offline forum summaries indicate the country and forum identification number. Online quotes note the forum name and participant ID. MaXQDA was used to assist in the coding and analysis of the texts.

Themes were coded based on definitions that required specific references by participants to change in relation to that issue. Some overlap is present, for example culture could encompass parents/elders, but it was coded for both only if respondents mentioned both “culture” and “parents”. The perspectives and positions given in these findings represent the majority of responses for each theme; some outlier examples are also noted.

Findings

If you could change one thing: community, sex and relationships

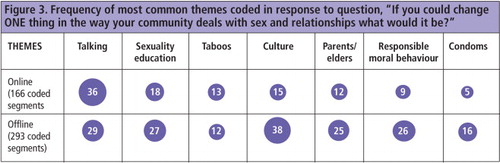

Here we present an applied thematic analysis of responses to the question: “If you could change ONE thing in the way your community deals with sex and relationships what would it be?” Citation15 This question was chosen because of its relevance to HIV, and its consistent usage in offline and online forums. The most extensively discussed items in both offline and online forums were: talking, sexuality education and taboos (

). However, offline forums tended to mention culture, responsible/moral behaviours, parents/elders, and condoms relatively more often.In the responses, the importance given above all was to the concept of “talking”, shown in mentions of talk/ing, discuss/ion/s, conversation/s. In each forum, participants pointed to:

“The belief that when you do not talk about sex and sexuality, and ignore it totally, it ceases to exist.” (Africa English online female participant No.332)

“They feel that since their parents don't want their children to engage in sexual activities, their parents avoid talking about sex. This results in people having unprotected sex.” (India offline forum No.34)

“Openness to me refers to that state where you are free to talk about sex or relationships in public places or to anyone with whom you like... it means a kind of freedom to me where no one has to fear for what they speak or with whom they are comfy...” (Asia Pacific online forum female participant No.330)

“Breaking frustration! Making sexuality a subject that it is mandatory to talk about instead of keeping it as ‘taboo and a source of sexual excitement or harm to religion’.” (Middle East and North Africa online forum No.381)

“I would like to change the taboo around sex, which is wrong. Before, we did not talk about sex because it was sacred. Now, everything is trivialized, but we still do not really talk about it. We don't know what we are afraid of, even though the facts are alarming: STIs and deaths from AIDS, pregnancy, abortion…” (Africa French online forum participant No.357)

Sexuality education

In discussing what they would change about how communities deal with sex and relationships, the concept of comprehensive sexuality education was talked about in various forms. This included how sex should be talked about, what should be discussed and with whom. In talking about sexuality education respondents often mentioned the need to change the format and the way in which sexuality education is taught:

“…[from a] lecture method approach to discussion method.” (Uganda Offline Forum No.1)

“[We] should talk about sex in a fun way by removing all the prejudices and show that [sex] is not a bad thing but is there in the very nature of man.” (Latin America online forum male participant No.338)

“They hold on to abstinence-only policies because of those who think that by informing others about protection and birth control we are encouraging them to have sex (which goes against beliefs). This isn't the case though. By teaching them all of the facts we are empowering them to make a well-informed decision for themselves and avoiding leaving them vulnerable if they decide to have sex (because people are going to have sex even when they are told not to).” (America, Europe and Caribbean online forum No.379)

“The “technical” way we talk about sex doesn't reflect the reality, and teenagers still have a lot of questions, ignorance and prejudice after the sessions. For example they may know how to use a condom, but using a condom could still be a taboo, and they wouldn't be able to say no to someone who wouldn't want to use a condom...” (America, Europe and Caribbean online forum participant No.343)

“We need to have more conversations on sex not just vaginal and penile sex, but anal and oral sex as well. To change the perception that anal and oral sex are only done by MSM… Anal sex, more persons, particularly women are now exploring anal sex because they want to ‘keep their man’.” (Guyana offline forum No.23)

“Most school-aged girls are engaging in unprotected anal sex as a way to preserve their virginity: ‘Mommy checks in front’.” (Guyana offline forum No.25)

“Appropriate sex education according to age is essential. Our community always feels uneasy when the topic is related with sex. We should be more open, talk about it in the light of education so kids would not hold any misunderstandings. Wrong belief can bring them to many things and mostly not good things. If the youth dare to ask, adults should have the courage to provide them with a suitable answer.” (Thailand offline forum No.39)

“I would like my community to encourage open talks about sex and relationships to younger people starting at the age of 10 years. This would address the issue of early sexual debut among young people, and young people will have more knowledge about sex and relationships before they enter adolescence and teenage.” (Kenya offline forum No.20)

Dispelling taboos at home and in the community

Throughout the CrowdOutAIDS process, young people called for dispelling taboos surrounding sex and sexuality at the family and community levels, including in arenas such as schools, to ensure young people can gain access to information about their sexual and reproductive health and make informed decisions about their lives. Taboos around sex and, in particular, young people engaging in sexual activity, were invoked by young people as “walls” that affected both their ability to access and use condoms and contraceptives, to access information and sexuality education, and to make use of health services, even where they do exist. Participants noted that in seeking to exercise their sexuality, they felt “demonised”, “judged”, and “stigmatised” (either based on their sexual orientation, because they engaged in premarital sex, or because they were female).

Yet, while the majority of young people engaged in the CrowdOutAIDS process saw these taboos as harmful, a minority expressed the need to reinforce them:

“Societies are allowing people to have sex freely… then the society has fallen. Please do not ask me if I am against women's rights and all, because I feel that giving rights to women does not mean that they should be allowed to give up modesty. These are all rights to degrade the human race.” (Asia Pacific online forum participant No.354)

“Empower women to be more independent from men, so they can have rights to choose, to express their feelings to sex, to enjoy sex, as well as to avoid risks of having sex.” (China online forum unknown participant)

“It is very important that parents as the first teachers for the children should have right knowledge and are also vocal on the subject. They should know how and when to talk with their children about it.” (Africa English online forum female participant No.375)

“Youth are also at fault for not sharing about relationship and sex with parents; we should also take the initiative to talk to them freely.” (Nepal offline forum No.15)

Gender and sexuality

Discussions in ten offline forums made explicit reference to issues involving gender inequality and violence. Advocating against gender-based sexual violence and abusive relationships were important priorities for change. One forum in Kenya came to the consensus that the one thing they would change is for “criminals not to rape their victims after robbing them”.

In particular, young people shared reflections around harmful gender norms in relation to the perceived position of women in society. These were voiced as blocks to development in various spheres, from personal to professional development.

“Even if a woman becomes successful, people tend to think that she achieved success only by luring men.” (Nepal offline forum No.15)

“Locking up of a girl-child indoors and restricting her from mingling with boys because of fear of a boy-girl friend relationship, as the parents think they may be involved in a sexual behaviour.” (Kenya offline forum No.33)

With regard to stigma and discrimination based on sexual orientation, participants called for equal rights and treatment for all, regardless of sexual orientation.

“Attitudes toward homosexuals need to be better... don't look down on us. We can work and study as good as everyone in the society does, please don't discriminate.” (Thailand offline forum No.39)

“Decriminalise homosexuality, strike out from the law the parts that say buggery and cross dressing are punishable offences.” (Guyana offline forum No.19)

Recommendations from participants: issues and strategies

“I believe that everyone has the right to choose what they need to do and they need to have sufficient information so that they can make informed decisions.” (Asia Pacific online forum participant No.360)

The outcome document of the CrowdOutAIDS process, CrowdOutAIDS: Strategy recommendations for collaborating with a new generation of leaders for the AIDS response Citation13 was drafted by a ten-member youth committee and presented to the UNAIDS Executive Director in Nigeria at the end of April 2012 by the volunteers who had hosted the CrowdOutAIDS community forums.

Since the launch, the UNAIDS Executive Director has publicly committed the UNAIDS Secretariat to implementing these recommendations, including in his speech to the UNAIDS Programme Coordinating Board in December 2012, and to establishing a Youth Advisory Forum for continuous feedback and input into the Secretariat's work, with the core mandate to advise on implementation.Citation14

The recommendations have affected the Secretariat's institutional priorities, with unprecedented human resources now being dedicated to the youth agenda –a team of nine, with two positions at headquarters and one youth officer in each Regional Support Team. The strategy recommendations are the foundation of the Secretariat's youth-related workplan and budget, and will be used to develop a Secretariat-wide youth policy and action plan.

A 2.0 version of CrowdOutAIDS.org has been developed, as called for in the strategy recommendations, to create a space for ongoing collaboration between the UNAIDS Secretariat and young people. Implementation started in early 2013 with the formation of the Youth Advisory Forum, and a meeting with youth organizations will be held in May 2013 to establish a joint pact for social transformation.

Discussion

Across different regions, online and offline forums, genders and perspectives, young people consistently identified the need to change the way in which communities deal with sex and relationships. These responses counter some of the claims made in the 2012 UN Commission on Population and Development that increased access to sexuality education was not what youth themselves actually want.Citation1 Instead, the CrowdOutAIDS online and offline forums expressed a clear need for comprehensive sexuality education. This also nuances the need to be sensitive to community values,Citation1 as it raises the question of whose values count in communities, given that young people themselves feel the need to challenge social taboos around sexuality within their own societies.

The consistency and similarities in this data-set across regions, offline and online, towards increasing communication about sex and sexual education are noteworthy. It is equally important to stress the diversity, however, as differences were seen within forums from the same country as well as in comparisons of offline and online groups. The major difference between the offline and online forums, in response to the “change one thing” question, was the emphasis placed by the offline forums on cultural aspects in their community and the need for morals and more “responsible” behaviour. The online forums, in contrast, gave much more emphasis to the need to open up communication and break the taboos surrounding issues of sex and relationships. We did not collect demographic information on all participants, but we hypothesize that the online participants had a higher socioeconomic background, were more globally exposed, had greater access to education and perhaps did not feel the same weight of cultural pressures or more conservative ideas about moral standards and behaviours. The importance of this variance is evident if we consider the difference in the outcomes, i.e. in the perspectives and priorities, if only one of these two groups had been involved in this process. Through the use of a hybrid of social media tools and recruiting volunteers from the online forums to host offline discussions, we sought to minimize bias and include young people from across different educational, socioeconomic, religious and political orientations. The end result was the creation of a unique space for gathering diverse perspectives, where all were accorded value.

It became evident that young people could not easily be dichotomized into “liberal/progressive” or “conservative” groups but shared a mix of “conservative” and “progressive” thinking. This belief — that there are two defined groups — often leads to misperceptions which may include assumptions that youth are somehow inherently “liberal”. On the other hand, “conservative” groups may accuse “progressive” women's rights organizations, as well as the UN, of not truly representing the voices of youth. Rather than engaging at one end of the spectrum or the other, our findings show that young people's views are dynamic and complex with a variety of perspectives on sex, sexuality and HIV, and how they wish to live their own lives. The CrowdOutAIDS process demonstrated that when youth are given the space, they can constructively discuss their differing perspectives and work together to create recommendations for action and a policy document that puts forward what they collectively identify as their priority issues. Through this process, young people acknowledged one another's differences, without overshadowing their points of agreement.

This process ensured that young people without internet access were able to participate. The extent of sub-Saharan African participation in the online forums, however, suggests that while internet penetration in Africa may be lower than the global average, the young people who are connected were eager to have their voices heard. The subject matter may also have resonated more with young people on that continent, given the fact that 78% of all young people living with HIV live in sub-Saharan Africa.Citation16

Crowdsourcing fostered the inclusion of sexual health and HIV youth activists but it also opened the base of participation beyond youth networks and organizations that are traditionally consulted by global institutions, to involve “ordinary” young people who may never previously have been involved in sexual health and HIV activism. Individuals did not have to be formally organized or part of a network or institution. Since they were able to sign up via an online platform, the risk of “cherry picking” activists from organizations was averted, adding legitimacy to the priorities outlined in the outcome document.

Young people have highlighted that if we are to stimulate discussion and put an end to the stigma and taboos surrounding talking about sex, “sexuality education” should target not only youth but also families, elders and society more broadly. Equipping these stakeholders with information and tools, not just how to talk about sex but also the actual content, is an important next step. Further, what we see in the data is that young people are not just identifying “others” who need to change, their parents-elders-society, they are asking for more space and the means for learning how to talk and learn about sex and relationships for themselves. Thus, these findings support previous research which argues that the most effective way to provide sexuality education is with a curriculum-based programme within the school or community setting that is implemented in conjunction with a broader strategy for social change.Citation16

Conclusion

With young people continuing to experience high rates of HIV and other STIs, unintended pregnancy, early marriage and gender-based violence, it is high time that decision-makers seriously reflect on what they need to do differently, to better meet the needs and uphold the rights of all young people. In doing so, it will be essential to ensure that actions embody the key principles identified by young people themselves, which call for respecting their views, fulfilling their right to meaningful participation and the leadership of young people at all levels within the human rights framework that is non-judgemental, promotes equality and seeks to end discrimination.

Political commitments, such as the resolution adopted at the Commission on Population and Development in 2011, are significant and mark historical progress in the global recognition of young people's human rights, including around sex and sexuality. Yet they must be followed by concrete action at the country level, fully involving young people, if they are to transcend the rhetoric.

The CrowdOutAIDS process enabled thousands of young people to directly engage with the UNAIDS Secretariat on issues of HIV and sexuality, and priority and strategy development. Young people were given the opportunity to engage in an open and horizontal process, debating key issues. The crowdsourcing approach generated ownership and commitment of young people to the final outcome document and showed that despite the digital divide, online tools can effectively be used to mobilize for offline action. Through leveraging social media and crowdsourcing, it is possible to integrate grassroots perspectives from a wide range of young people across the globe into high-level strategy and policy processes. This new model of engagement and participation should be further explored for community empowerment and mobilization.

Acknowledgements

The UNAIDS Secretariat provided funding for the CrowdOutAIDS project. The authors wish to acknowledge the whole CrowdOutAIDS team, including moderators and drafting committee members, and all open forum participants, both online and offline in communities around the world, as well as the volunteers who hosted these forums.

Notes

* Crowdsourcing is a distributed problem-solving and production model. Problems are broadcast to an unknown group of solvers in the form of an open call for solutions. Users – also known as the crowd – submit solutions.

References

- UN Commission on Population and Development. Resolution 2012/1 Adolescents and youth. 2012. http://www.un.org/esa/population/cpd/cpd2012/Agenda%20item%208/Decisions%20and%20resolution/Resolution%202012_1_Adolescents%20and%20Youth.pdf

- Youth Coalition Watchdog. 45th Session of the Commission on Population and Development Issues 1, 2 and 3. 2012. http://www.youthcoalition.org/html/index.php?id_art=370&id_cat=7

- Global Interagency Task Team on HIV and Young People. Securing the Future Today: Synthesis of Strategic Information on HIV and Young People. 2011; UNAIDS: Geneva.

- UNICEF. Children & young people: participating in decision-making. Undated.

- SPW/DFID-CSO Youth Working Group. Youth participation in development: A guide for development agencies and policy makers. March 2010. http://bit.ly/MKigok

- UN General Assembly. Political Declaration on HIV and AIDS: Intensifying our efforts to eliminate HIV and AIDS. A/65/L77. Sixty-fifth session; 2011.

- Wikipedia. Crowdsourcing. 17 April 2012. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crowdsourcing

- C McNab. What social media offers to health professionals and citizens. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 87: 2009; 566.

- R Goodspeed. Crowdsourcing tools for public participation in planning, 2012. media/uploads/DataDay2012_Goodspeed-New_Tools_for_Collecting_Data-handout.pdf

- TF Sigurdsson. Writing a new constitution. How the public was involved. 2011; Iceland Constitutional Council: Geneva. (Unpublished).

- Internet World Stats. Internet usage statistics: the internet big picture world internet users and population stats; 2011. http://www.internetworldstats.com/stats.htm

- M Patton. Qualitative research and evaluation methods 3rd ed. 2002; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks.

- CrowdOutAIDS. CrowdOutAIDS: Strategy recommendation for collaborating with a new generation of leaders for the AIDS response. 2012. http://bit.ly/LzNSkj

- M Sidibé. Unprecedented progress, but AIDS is not over: Maintaining commitment for the next 1000 days and opportunities for the post-2015 era; 2012. http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/speech/2012/12/20121211_SP_EXD_31st_PCB.pdf

- G Guest, KM MacQueen, EE Namey. Applied Thematic Analysis. 2012; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks.

- UNESCO. International technical guidance on sexuality education: an evidence-informed approach for schools, teachers and health educators. Paris: Section on HIV and AIDS Division for the Coordination of UN Priorities in Education; 2009.