Abstract

The Government of India has started a new scheme aimed at offering sanitary pads at a subsidized rate to adolescent girls in rural areas. This paper addresses menstrual health and hygiene practices among adolescent girls in a rural, tribal region of South Gujarat, India, and their experiences using old cloths, a new soft cloth (falalin) and sanitary pads. Qualitative and quantitative data were collected in a community-based study over six months, with a pre-and post- design, among 164 adolescent girls from eight villages. Questions covered knowledge of menstruation, menstrual practices, quality of life, experience and satisfaction with the different cloths/pads and symptoms of reproductive tract infections. Knowledge regarding changes of puberty, source of menstrual blood and route of urine and menstrual flow was low. At baseline 90% of girls were using old cloths. At the end of the study, 68% of adolescent girls said their first choice was falalin cloths, while 32% said it was sanitary pads. None of them preferred old cloths. The introduction of falalin cloths improved quality of life significantly (p<0.000) and to a lesser extent also sanitary pads. No significant reduction was observed in self-reported symptoms of reproductive tract infections. Falalin cloths were culturally more acceptable as they were readily available, easy to use and cheaper than sanitary pads.

Résumé

Le Gouvernement indien a lancé un plan qui propose des serviettes hygiéniques à prix subventionné aux adolescentes vivant dans les zones rurales. Cet article aborde la santé menstruelle et l'hygiène des adolescentes dans une région tribale rurale du Gujarat méridional, et leur expérience de l'utilisation de vieux chiffons, d'un nouveau tissu doux (falalin) et de serviettes hygiéniques. Les données qualitatives et quantitatives ont été recueillies par une étude communautaire sur six mois, avec évaluation préalable et postérieure, auprès de 164 adolescentes originaires de huit villages. Elles ont été interrogées sur leurs connaissances de la menstruation, leurs pratiques menstruelles, leur qualité de vie, l'utilisation et la satisfaction avec les différents linges/serviettes et les symptômes d'infections de l'appareil reproducteur. Elles connaissaient mal les changements de la puberté, la source des règles et la voie de l'urine et du flux menstruel. Au début de l'étude, 90% des adolescentes utilisaient de vieux chiffons. À la fin de l'étude, 68% des filles ont déclaré que leur premier choix était le linge en falalin, contre 32% pour les serviettes hygiéniques. Aucune n'a préféré les vieux chiffons. L'introduction des linges en falalin a sensiblement amélioré la qualité de vie (p<0,000) comme, dans une moindre mesure, les serviettes hygiéniques. Aucune réduction notable des symptômes auto-signalés d'infections de l'appareil reproducteur n'a été observée. Les linges en falalin étaient culturellement plus acceptables car les adolescentes pouvaient se les procurer et les utiliser aisément, et ils étaient moins onéreux que les serviettes hygiéniques.

Resumen

El Gobierno de India ha puesto en marcha un nuevo plan para ofrecer toallas sanitarias a una tarifa subsidiada a las adolescentes de zonas rurales. En este artículo se trata la salud menstrual y las prácticas de higiene entre las adolescentes de una región tribal rural de Gujarat meridional, en India, y sus experiencias usando paños viejos, un paño suave nuevo (falalin) y toallas sanitarias. Durante un plazo de seis meses, se recolectaron datos cualitativos y cuantitativos en un estudio comunitario, con un diseño preliminar y posterior, entre 164 adolescentes de ocho poblados. Las preguntas abarcaron sus conocimientos de la menstruación, prácticas menstruales, calidad de vida, experiencia y satisfacción con los diferentes paños y toallas sanitarias, y síntomas de las infecciones del tracto reproductivo. Pocas tenían conocimientos de los cambios relacionados con la pubertad, la fuente de la sangre menstrual y la vía del flujo urinario y menstrual. En la línea base, el 90% de las adolescentes estaban usando paños viejos. Al final del estudio, el 68% dijo que su primera elección era el paño falalin, mientras que el 32% dijo que prefería las toallas sanitarias. Ninguna prefirió los paños viejos. La introducción del paño falalin mejoró la calidad de vida considerablemente (p<0.000) y a menor grado también las toallas sanitarias. No se observó ninguna reducción significativa en los síntomas autoreportados de infecciones del tracto reproductivo. Los paños falalin fueron más aceptados culturalmente, ya que eran fáciles de adquirir y usar y más baratos que las toallas sanitarias.

Twenty-five per cent of the population of India were adolescents in 2011.Citation1 Menstruation is a normal physiological process but the onset of menstruation is a unique phenomenon for adolescent girls. In India, it is considered unclean, and young girls are restricted from participating in household and religious activities during menstruation. These restrictions extend to eating certain foods like jaggery and papaya as well.Citation2,3

Awareness about menstruation prior to menarche was found to be low among both urban and rural adolescents in Maharashtra state.Citation3 The limited knowledge available was passed down informally from mothers, who were themselves lacking in knowledge of reproductive health and hygiene due to low literacy levels and socioeconomic status.Citation4 Lack of menstrual hygiene was found to result in adverse outcomes like reproductive tract infections.Citation4,7 Better knowledge about menstrual hygiene reduced this risk.Citation4 Young girls in urban slums of Karachi, Pakistan, found it difficult to manage menstrual hygiene because of lack of infrastructure to dispose of used cloths in school and lack of privacy to dry washed ones at home.Citation5 Lack of privacy to manage menstrual hygiene in school was associated with absenteeism among adolescent girls in Nepal.Citation6

Absorbent pads used to manage menstrual blood loss are an important need of adolescent girls. Though sanitary pads are used universally in high-income countries, a large study in India showed that only 12% of menstruating women used sanitary pads and 70% of women cited cost as a major barrier for using them.Citation8

In June 2011, the Government of India launched a new scheme to make sanitary pads available in selected rural areas at a subsidized cost of Rs 6 per pack of six sanitary pads by accredited social health activists (ASHAs) who are village-based frontline health workers.Citation9 The Government envisaged that sanitary pads would be manufactured by self-help groups to strengthen their economic activities.Citation10

Sharda Mahila Vikas Society (SMVS) is a voluntary development organization promoting women's awareness and empowerment. SMVS is located in a rural, tribal area of Jhagadia block, South Gujarat, India. 68% of the population in Jhagadia block belong to scheduled tribes. The female literacy rate is only 52% and 40% of the population are landless labourers. Most tribal households live below the poverty line; 96% live in mud houses and 74% have electricity available at home. SMVS's work with adolescent girls and boys includes promotion of hygienic practices, anaemia control, creating awareness about drug addiction, and life skills development. These activities are carried out through teaching sessions in schools and in the community, along with regular workshops at SMVS's headquarters.

While implementing an adolescent health and awareness programme locally, SMVS observed problems related to the use of the subsidized sanitary pads due to irregular supply, lack of awareness of how to use them, the sub-optimal quality of the pads, and non-availability of appropriate means of disposal, which resulted in low acceptability. Instead, we found that to manage menstruation, adolescent girls were using old cloths made from their mothers' petticoats (chaniya), bed sheets, or pants, which were washed and re-used. We also came to know about the use of falalin cloths locally, a soft, wool-like cloth with good absorption capacity, which were also reusable and were accessible to adolescent girls in the market, costing approximately Rs.20 (US$0.40) per piece. However, we discovered that no data were available about effectiveness or user satisfaction with falalin cloths. We also observed that tribal girls had a low level of knowledge about menstruation and pubertal changes.

To learn more and fill in these gaps in knowledge, SMVS launched a study of adolescent girls' knowledge regarding menstruation and menstrual practices; their quality of life, experience and satisfaction with three different kinds of menstrual pads — old cloths, a new soft cloth (falalin) and subsidized sanitary pads — and any differences in symptoms of reproductive tract infection using these three kinds of pads.

Methodology

The study was conducted from January to July 2011 among adolescent girls living in an under-privileged area in all eight project villages. All school-going and non-school-going adolescent girls residing in the study area had been registered with the adolescent awareness programme (total 215) and were eligible to be included in the study. Those who had not entered menarche, were married, had only recently migrated to the study villages or were not available for data collection at baseline were excluded, leaving 164 eligible girls.

Verbal consent was obtained from the girls and their mothers after explaining details of the study. Privacy was ensured and nobody else, including mothers, was present during data collection. Personally identifiable information was removed from the dataset and was only accessible to the principle investigator.

The intervention consisted of introducing falalin cloths, followed by sanitary napkins, among girls who were using old cloth at baseline. First, the new falalin cloths were offered to all adolescent girls for three months at the subsidized price of Rs.10 (US$0.20) per piece (reused for three cycles) through village-based ASHAs. ASHAs were trained and supervised by SMVS staff and were given incentives for this work during the study. Subsequently, sanitary pads were procured from Raasi Napkins Shree Mahalaxmi Industries, Coimbtore, Tamil Nadu (SHG), which were offered for another three months at the subsidized cost of Rs.5 (US$0.10) per pack of eight pads, also through the ASHAs. Programme supervisors visited the study villages monthly to ensure the intervention was being implemented as planned.

Data were collected at baseline and again three months after introducing each of the two kinds of absorbent pads. To fulfil our objectives related to acceptability, effectiveness and quality of life, we assumed three months per each type of pad was adequate. However, with hindsight, three months might not have been enough to study any effect on symptoms of RTIs.

Data collection and analysis

Both qualitative and quantitative methods of data collection were used. Open-ended questions were asked to know reasons for their practices and preferences. Commonly encountered responses related to quality of life were identified during previous work by SMVS with adolescent girls and focus group discussions which were subsequently used for designing the data collection tool for this study. The tool was used for interviews with adolescent girls by trained female research assistants. Some of the questions asked were related to knowledge and sources of information about menstruation, perceptions and practices regarding menstruation and use of old cloth, quality of life and symptoms of RTIs, bodily changes at puberty, dietary and activity-related restrictions during menstruation, type of absorbent pads used and their availability. Questions regarding absenteeism from school or work, feelings of discomfort, washing and drying problems, disposal issues, and vaginal discharge were also asked. After three months of use of the two other absorbent pads, the same data collection tool was administered to obtain information regarding the users' experience of quality of life and symptoms of RTIs.

Each village and adolescent girl was coded. Data accuracy was checked by the supervisor. Dichotomous variables were created for categorical variables related to quality of life issues and RTIs. Pairs were matched first among old cloth and falalin users, then among falalin and sanitary pad and among old cloth and sanitary pad users. For every variable, proportion was calculated, difference in proportions was computed and significance was tested using t-test for matched pairs. Unmatched pairs were excluded from comparison. For data analysis SPSS-17 version was used.

Six in-depth interviews and two focus group discussions with 26 adolescent girls were conducted using guidelines in the local language, in four villages at baseline and after three months of using each absorbent pad. After establishing rapport, the principal investigator conducted interviews till saturation point for eliciting new information was reached. Interviews were recorded both manually and on a recorder. Interviews were later transcribed and translated into English. Data were labelled, sorted, synthesized and analyzed manually by themes and sub-themes by the principle investigator. Secondary analysis of data, study design and tools were approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee of the Indian Institute of Public Health, Gandhinagar, India.

Any girl requiring medical assistance for a menstrual problem was referred to SEWA Rural hospital. Girls were made aware of aspects of menstrual health and hygiene, pubertal changes, menstruation and fertility, once data collection was over through the adolescent programme, including via discussions, role-plays, and body mapping.

Findings

The mean age of the 164 adolescent girls was 13.7 years (range 12–22 years). 148 (91%) were tribal, 131 (80%) were living in low-cost mud houses, 153 (93%) had at least primary level formal education, 55 (33.5%) were school-going, the rest were labourers 58 (36.6%) or did housework 45 (27.4%), 75% were from below-poverty-line families. Two-thirds of their mothers and one-third of their fathers were illiterate. 49 (30%) were underweight (BMI<18.5). Only 26 (16%) of the girls had adequate bathroom facilities available at home and the rest had makeshift bathrooms (navniyu) whose walls were made of sticks and plastic without a door, roof or running water.

Almost half the girls had to sit separately during menses, 89% were restricted in what they could touch, and almost half experienced changes in the behaviour of family members. Almost a third were not allowed to go outside the house alone during their periods.

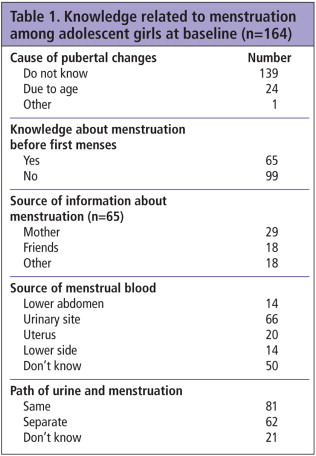

shows that most of the respondents lacked correct knowledge and understanding about the reproductive organs and physiology of menstruation. Adolescent girls faced many restrictions and most of them used old cloths to manage menstrual fluids.Qualitative findings revealed that due to lack of privacy, the girls took baths and washed their menstrual cloths early in the morning, before other family members woke up or were not around. At school or workplace, they would use a bulky piece of cloth which could absorb more menstrual blood but they were still always worried about spoiling their dresses. Toilets were non-existent at their workplaces (farms) and in most of their schools. If there were toilets in the schools they usually did not have running water.

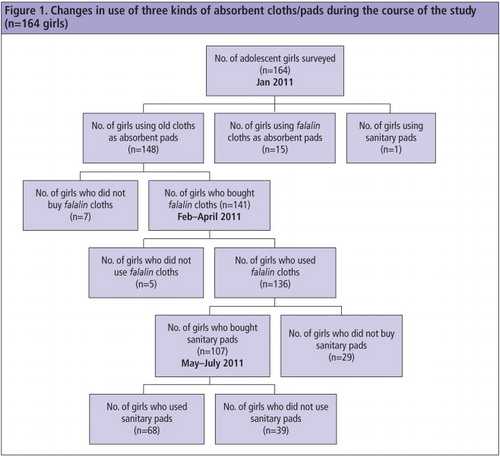

At baseline, 148 of the 164 girls were using old cloths, 15 were using falalin cloths and only one was using sanitary pads; 88 girls knew that falalin cloths were available in the market, while 76 did not, and 59 girls knew sanitary pads were available in the market, while 105 did not.

Perspectives on the three kinds of menstrual cloth/pads

Old cloths

“After repeated use (3–4 menstrual cycles), old cloths become stiff and we get abrasions on the skin of our inner thighs.”

“Stains of menstrual blood are visible on old cloths and it smells, we feel dirty and ashamed.”

“We feel unclean with the old cloths.”

Falalin

“Falalin cloths are easy to wash.”

“The new cloth is good because it is easy to dry, stains are not visible as it is red coloured and we could dry it easily in an open place in sunlight.”

“We used to have skin abrasions on our inner thighs with the old cloths, but not anymore with the falalin.”

Sanitary pads

Only a few girls opted to use the sanitary pads, but they were quite positive about them.

“We would like to use them, if pads are available in the village at an affordable cost.”

“Pads are better as no need to wash.”

“We will use them if available from government at low cost.”

“During menstrual periods we can't play at school, we just sit in the classroom, but we will be able to play now with sanitary pads.” (They were afraid that the old menstrual cloths might fall out while they were playing.)

“We don't like sanitary pads as they spoil our clothes.”

“Sanitary pads need to be changed more frequently.”

With disposal of sanitary pads, they believed that: “if we throw away the used pad in an open place and a snake sees it, it will become blind and we may become infertile”.

When we asked “in the absence of government supply of sanitary pads, what you will do?” they said: “If we don't get it from government, we will use falalin cloths.”

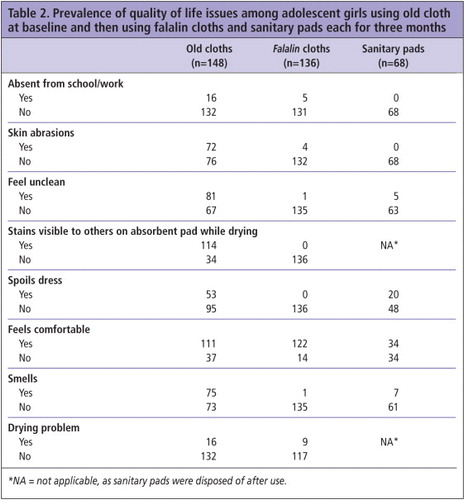

As regards symptoms of reproductive tract infections (RTIs) among the girls, 51 of 148 old cloth users (34%), 22 of 136 falalin cloth users (16%) and 9 of 68 sanitary pad users (13%) said they had a vaginal discharge. Symptoms of discharge that are usually related to RTIs (presence of yellow or foul-smelling discharge or itching with white discharge) were reduced among falalin cloth and sanitary pad users as compared to old cloth users, but the reduction was not statistically significant (data not shown).

The prevalence of most of the undesirable quality of life issues was significantly lower (p<.005) when adolescent girls used falalin compared to use of old cloths at baseline. There was no difference in prevalence of RTI symptoms. Most of the undesirable quality of life issues were also significantly lower (p<.005) when adolescent girls used sanitary pads compared to use of old cloths at baseline, except getting their cloth spoiled (p<0.84). Again, there was no difference in prevalence of RTI symptoms. The prevalence of most of the undesirable quality of life issues was significantly higher (p<.005) when adolescent girls used sanitary pads compared to use of falalin cloths. Again, there was no difference in prevalence of symptoms of RTIs (data not shown).

The mean number of adverse quality of life issues suffered by the girls were 4.78, 0.32, and 1.3 from old cloths, new cloths and sanitary pads, respectively. The highest number of adverse quality of life issues were found with old cloths and the least with falalin cloths.

After three months, 136 girls had used falalin cloths and at the end of six months 68 girls had used sanitary pads (). At the end of the study, 68% of adolescent girls stated that their first choice for their menstrual needs was falalin cloths, while 32% indicated that sanitary pads were their first choice. None of them preferred old cloths.

Discussion and recommendations

This study showed that most of the adolescent girls did not have correct knowledge about menstruation, and unhygienic practices were widely prevalent, including social restrictions involving household activities and food items. Most of the adolescent girls were using old cloths at the beginning of study. Use of old cloths has been linked to microbial growth,Citation11 and the girls in this study had a high prevalence of symptoms indicative of RTIs.

The low level of knowledge and undesirable practices found in this study are similar to findings in other communities in South Asia and Africa.Citation2,5,6,12,13 This finding underlines the need for education and awareness regarding menstrual hygiene.Citation2,5,12,14–17 Undesirable attitudes towards menstruation on the part of family members have been reported in other studies too.Citation2,4,18 Community-based health education programmes could bring significant improvement in their awareness regarding management of menstrual hygiene.Citation12,19

Acceptance of the new falalin cloth was because it is easily washable and convenient to dry in the open, reusable, soft, and has good absorbing capacity. New cloth falalin is culturally more acceptable in the society. Most importantly, it is easily available at the community level at low cost and is environmentally friendly as it is disposed of easily by burning. As a result of this study, we decided to promote use of falalin cloth in other project villages and added a menstrual hygiene awareness module in our programme. There are serious concerns regarding implementation of the government's programme offering sanitary pads at a subsidized rate, especially regarding acceptability, supplies and disposal. Similar concerns were observed among adolescent girls of another studyCitation5. Considering this, the new cloth falalin potentially provides an option to improve menstrual hygiene though more robust research is required to assess its effectiveness.

This study provides clear evidence of the need for strategies to improve menstrual hygiene among adolescent girls in rural settings in India. It also shows there is a strong need for adolescent-friendly services to provide information about reproductive health and menstrual hygiene, which should be incorporated in the school curriculum. Female teachers, peer educators and mothers also need information on these matters and to be trained to provide accurate and supportive information to adolescent girls. Moreover, water and sanitation at school, in workplaces and at home need to be addressed to reduce the need for unhygienic practices and reproductive tract infections, in line with Millennium Development Goals 2, 3 and 7.

Along with sanitary pads, access to falalin cloths needs to be scaled up and requires further promotion in India, especially in rural settings, where adolescent girls are experiencing difficulties using sanitary pads. Proper steps also need to be taken to overcome these difficulties, mainly related to quality of the subsidized sanitary pads, lack of awareness and of means of disposal. Awareness about the scheme, how to use both falalin cloths and pads and their benefits should be increased in communities, and can be provided by ASHAs and others at the community level, in NGOs and in schools as well as on the farms where girls are employed. An uninterrupted, regular supply of good quality sanitary pads and falalin cloths, and plans for disposal, need to be addressed at these levels as well. Vending machines could perhaps be installed in schools and colleges, along with disposal incinerators, but only where power outages are not an issue and resources are adequate to allow for these items to be accessible to all. The role of market providers and local manufacture of menstrual products needs further investigation and planning.

Both falalin cloths and sanitary pads were very quickly shown to be acceptable to a large proportion of adolescent girls in this study; given the clear improvements in quality of life issues related to menstruation with their use, both methods need to be made readily available and easily affordable for rural, tribal girls and others living in poverty in India.

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted as part of a post-graduate diploma in public health management of Dr Shobha Shah. The authors are grateful to research assistants Mrs Ranjan Atodariya and Miss Gaytri Patel for data collection and Mr Rajnikant Patel for providing support for statistical analysis. Adolescent girls and their mothers in the community are especially acknowledged, without whom this study would not have been possible. Technical guidance and support from the Indian Institute of Public Health-Gandhinagar, was critical to appropriate documentation. The Sharda Mahila Vikas Society received a grant from the Share and Care Foundation, USA, for this project.

References

- UNICEF. The State of World's Children: Adolescence, An Age of Opportunity. 2011; New York.

- DK Drakshavani, RP Venkata. A study on menstrual hygiene among rural adolescent Indian girls. Andhrapradesh. Indian Journal of Medical Science. 48(6): 1994; 139–143.

- D Deo, DC Ghataraj. Perceptions and practices regarding menstruation: a comparative study in urban and rural adolescent girls. Indian Journal of Community Medicine. 30: 2005; 33–34.

- A Dasgupta, M Sarkar. Menstrual hygiene: how hygienic is the adolescent girl?. Indian Journal of Community Medicine. 33(2): 2008; 77–80.

- TS Ali, SN Rizvi. Menstrual knowledge and practices of female adolescents in urban Karachi, Pakistan. Journal of Adolescents. 33(4): 2010; 531–541.

- Wateraid. Is Menstrual Hygiene and Management an issue for adolescent school girls in Nepal. 2010; Kathmandu.

- MK Naik. A study of the menstrual problems and hygiene practices among adolescents in secondary school. Thiruvanthepuram Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 1: 2012; 79.

- Kounteya Sinha, TNN. Times of India. 23 January 2011.

- Press Information Bureau, Government of India. Government approves scheme for menstrual hygiene of 1.5 crore girls to get low-cost sanitary napkins. 2010. http://pib.nic.in/newsite/erelease.aspx?relid=62586v

- S Matharu. Menstrual hygiene scheme to be expanded. Changes brought under National Rural Health Mission for better implementation of schemes. Governance Now. www.governancenow.com/news/regular-story/menstrual-hygiene-scheme-be-expanded. 22 June 2011.

- UM Lawan, NW Yusuf, AB Musa. Menstruation and hygiene amongest adolescent girls in Kano. Nigeria. African Journal Reproductive Health. 14(3): 2010; 201–207.

- E Alaha, E Elsabjh. Impact of health education information on knowledge and practice about menstruation among female secondary school students in Zigzag city. Journal of American Science. 7(9): 2011; 737–741.

- India Sanitation Portal. http://indiasanitationportal.org/. October 2011.

- MK Shazly, MH Hassanein, AG Ibrahim. Knowledge about menstruation and practices of nursing students affiliated to University of Alexandria. Journal of Egypt Public Health Association. 65(5–6): 1990; 509–523.

- P Adhikari, B Kadel, SI Dhungel. Knowledge and practice regarding menstrual hygiene in rural adolescent girls of Nepal. Kathmandu University Medical Journal. 5(3): 2007; 382–386.

- I Swenson, B Havens. Menarche and menstruation: a review of the literature. Journal of Community Health Nursing. 4(4): 1987; 199–210.

- AR Dongre, PR Deshmukh, BS Garg. The effect of community-based health education intervention of management of menstrual hygiene among rural Indian adolescent girls. World Health Population. 9(3): 2007; 48–54.

- Religious taboos on menstruation affects reproductive health of women. Conference proceedings, Asian-Pacific Conference on Reproductive and Sexual Health, 29–31 October 2007.

- TS Ali, N Sami, AK Khuwaja. Are unhygienic practices during the menstrual, partum and postpartum period a risk factor for secondary infertility?. Journal of Health Population Nutrition. 25(2): 2007; 189–194.