Abstract

Sex education has been included in the National Curriculum of the Brazilian Ministry of Education since 1996 as a cross-cutting theme that should be linked to the contents of each school subject in primary and high schools. This paper presents a study of the implementation of this policy in the primary schools of Novo Hamburgo, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, based on interviews between January 2011 and April 2012 with 82 teachers working in those schools. We found that sex education was not being taught as a cross-cutting theme in any of the schools, and that any lessons were mostly dominated by a biomedical discourse focusing primarily on the reproductive organs, fertility, pregnancy, and contraception. Sexual health and relationships and non-heterosexual sex and relationships were being neglected. Sex education was also considered a possible means of correcting or controlling sexual identities and behaviours deemed abnormal or immoral. We recommend far more discussion of how to implement the National Curriculum recommendations. We call for education courses to provide theoretical and methodological training on sex education for teachers, and recommend that the boards of educational institutions take up sex education as a priority subject. Lastly, we suggest that each school studies local sexuality-related problems and based on the findings, each teacher presents a pedagogical proposal of how to integrate sex education into the subjects they teach.

Résumé

L'éducation sexuelle est au programme d'études national du Ministère brésilien de l'éducation depuis 1996 comme discipline transversale devant être liée aux contenus de chaque matière scolaire dans l'enseignement primaire et secondaire. L'article présente une étude sur la mise en łuvre de cette politique dans les écoles primaires de Novo Hamburgo, Rio Grande do Sul, Brésil, sur la base d'entretiens menés entre janvier 2011 et avril 2012 avec 82 enseignants de ces écoles. Nous avons constaté qu'aucune des écoles n'enseignait l'éducation sexuelle comme discipline transversale et que les cours étaient le plus souvent dominés par un discours biomédical se centrant principalement sur les organes reproducteurs, la fécondité, la grossesse et la contraception. Ils négligeaient la santé et les relations sexuelles, de même que les rapports non hétérosexuels. L'éducation sexuelle était aussi considérée comme un moyen possible de corriger ou de contrôler les identités et les comportements sexuels jugés anormaux ou immoraux. Nous recommandons d'intensifier les discussions sur la manière d'appliquer les recommandations relatives au curriculum national. Nous demandons que les cours dispensent aux enseignants une formation théorique et méthodologique sur l'éducation sexuelle et préconisons que les conseils d'administration des institutions éducatives considèrent l'éducation sexuelle comme une discipline prioritaire. Enfin, nous suggérons que chaque école étudie les problèmes locaux relatifs à la sexualité et, sur la base des conclusions, que chaque enseignant présente un projet pédagogique sur la manière d'intégrer l'éducation sexuelle dans la matière qu'il enseigne.

Resumen

En 1996, la educación sexual fue incluida en el Currículo Nacional del Ministerio de Educación de Brasil como un tema transversal que debería vincularse con el contenido de cada materia de enseñanza primaria y secundaria. En este artículo se presenta un estudio de la aplicación de esta política en las escuelas primarias de Novo Hamburgo, Rio Grande do Sul, en Brasil, basado en entrevistas realizadas entre enero de 2011 y abril de 2012 con 82 maestros que trabajaban en esas escuelas. Encontramos que en ninguna de las escuelas se estaba enseñando la educación sexual como un tema transversal y que, si había lecciones, éstas eran dominadas en su mayoría por un discurso biomédico centrado principalmente en los órganos reproductivos, fertilidad, embarazo y anticoncepción. Se hizo caso omiso de la salud y relaciones sexuales y del sexo y las relaciones no heterosexuales. Además, la educación sexual era considerada como un posible medio de corregir o controlar identidades sexuales y comportamientos considerados anormales o inmorales. Recomendamos discutir más a fondo cómo poner en práctica las recomendaciones del Currículo Nacional. Hacemos un llamado a que en los cursos educativos se ofrezca a los profesores formación teórica y metodológica sobre la educación sexual y recomendamos que los consejos de las instituciones educativas den prioridad a la educación sexual. Por último, sugerimos que cada escuela estudie los problemas locales relacionados con la sexualidad y, según los hallazgos, que cada maestro presente una propuesta pedagógica sobre cómo integrar la educación sexual en las materias enseñadas.

Teenage pregnancy is most decisively a worldwide preoccupation. The fifth of the United Nation's Millennium Development Goals, which refers to the improvement of maternal health, emphasises the need to reduce teenage pregnancy due to its close relationship with infant mortality.Citation1

Data analysed by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics showed that there has been only a small reduction in teenage pregnancy rates in Brazil in the last ten years in spite of campaigns for the use of condoms and better access to contraceptive methods.Citation2 At the same time, a significant trend of rising numbers of pregnancies among teenagers aged 10–14 has been recorded. From 1998 to 2008, the number of pregnancies in the 10–14 year-old age group rose from 16,000 to 22,000. This trend has been seen especially among girls living in poorer socioeconomic conditions, although the phenomenon is also present among girls in the middle and upper classes.Citation3,4

Nationally, one in ten school students became pregnant before the age of 15 and approximately 75% of teenage mothers dropped out of school according to a national study conducted in 2008. Teenage pregnancies are even more worrying in the north or northeast regions of the country, where births to teenage girls between the ages of 10 and 19 years represented 22% of total births in 2009, while this proportion was 17% or less in the rest of the country.Citation5

In Novo Hamburgo, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, where the study reported in this paper took place, the proportion of births to teenage mothers accounted for 17% of all births in 2010.Citation6 In 2007, interviews with teenage mothers in Novo Hamburgo found that topics related to sexuality, pregnancy and birth control were generally not talked about in the girls' families.Citation7

Difficulties discussing sexuality among the young also appeared in another study carried out in the region in 2010, in a public high school in Porto Alegre, South Brazil. Graffiti in the school bathrooms were photographed and analysed. It showed that the drawings and messages that pupils leave on high school bathroom walls portrayed their concerns and beliefs concerning sexuality, among them statements about homosexuality, heterosexuality and transsexuality. Astonishingly, all these forms of sexuality were not criticised but seemed to be accepted by the graffiti artists and those observing and commenting on the graffiti. This study concluded that the images and text on these bathroom walls tended to give space to topics that cannot be discussed elsewhere. That study argued that the needs and concerns of pupils concerning sexuality are not addressed, or at least not completely enough, by school officials and teachers. Furthermore the graffiti showed a huge potential for productive classroom discussions about different sexualities, which had previously gone unnoticed.Citation8

We therefore decided to explore how and by whom sex education was being provided in Novo Hamburgo schools. Several questions emerged: What is happening in schools when it comes to sex education? Who plans, organises and delivers it? What are the purposes behind its implementation? Which topics are discussed, which aren't and why?

These questions laid the foundations for the project “Bodies, places and destinations: an analysis of sex education” sponsored by Feevale University which, since January 2011, has helped us carry out research on sex education in state primary schools in the city of Novo Hamburgo.Footnote*

Sex education in Brazil

In December 1996 the Parâmetros Curriculares Nacionais (National Curriculum Parameters) were established by the National Congress in order to regulate the contents of the school curriculum by year and describe the compulsory cross-cutting themes for all schools in the country. In this curriculum, sex education was to become part of curricular as well as extracurricular activities in all Brazilian schools, both in primary schools and high schools. It was not supposed to become a specific school subject as such, but a compulsory subject that should be discussed by using two approaches: through scheduled activities, including classroom activities and extracurricular projects, conferences and workshops; and spontaneously, whenever a situation arose related to sexuality.Citation8

The National Curriculum stressed the need to abandon models of sex education that (re)produce discrimination and exclusion, in order to create inclusive spaces in favour of sexual tolerance and diversity. For example, it says that the curriculum should be organized so that students are able to:

| • | respect the diversity of values, beliefs and behaviours related to sexuality, and recognising and respecting the different forms of sexual attraction; | ||||

| • | understand the search for pleasure as a right; | ||||

| • | identify and rethink taboos and prejudices related to sexuality, avoiding discriminatory behaviours; | ||||

| • | recognise the characteristics socially attributed to male and female gender as cultural constructions; | ||||

| • | act in solidarity with people living with HIV and with public health initiatives for prevention and treatment of sexually transmitted infections and HIV; | ||||

| • | be familiar with and adopt safer sex practices for preventing the transmission of sexually transmitted infections and HIV; | ||||

| • | know how to prevent unwanted pregnancy, where to seek advice and use of contraceptive methods.Citation8 | ||||

The National Curriculum is significant not only because it formalised sex education in schools as a compulsory, cross-cutting subject but also because the intended content conforms with the demands of the Brazilian feminist and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) movements, which have denounced the hierarchies, regulations and exclusions that on many occasions had been established and reproduced in sex education classes.Citation9

Unfortunately, it was not accompanied by a parallel process of preparing teachers, as has occurred with other compulsory cross-cutting themes such as environmental issues, and there were no significant changes made in the syllabus of university education courses to ensure that new teachers were prepared to teach sex education that covered a wide range of issues, including sexual diversity.Citation10

Initiatives addressing theoretical and methodological issues have been developed to assist teachers in dealing with various themes in sex education, but on many occasions these initiatives have been attacked by religious groups that have an important political presence at all levels of decision-making in the country. For example, in 2008, the Ministry of Health and Education launched a project entitled Escola sem homofobia (School without Homophobia), given the difficulties teachers have had in dealing with this subject, based on the results of national research in 2003 on the extent of homophobia in schools and other research which showed that 99% of school students acknowledged some degree of rejection towards the LGBT population and that one person was being murdered due to homophobia every two days in Brazil. The project received funding of 1.9 million Brazilian reais (US$3.9 millon). A range of materials were developed to help teaching staff in sex education activities, which should have been distributed in 2012 in 6,000 high schools, i.e. approximately 23% of the total of high schools in the country. The material included a brochure with guidelines and concepts on sexuality, an introductory letter to school principals, dissemination posters, six leaflets directed at students, and five short films.Citation11

The five short films were commissioned from several non-governmental organizations supported by the ECOS group (Communication in Sexuality). In 2010, two of these films were “leaked” on the internet before their official presentation and were criticized by the so-called Evangelical Parliamentary Front of the National Congress, which in May 2011 threatened to vote against any measure that was tabled in the National Congress by the government party until the production of these materials was suspended. They referred to the project as the “Gay Kit” and accused the Minister of Education of wanting to turn schools into preparatory academies for homosexuals, abolish the family and promote bisexuality.

The two videos that were leaked on the internet were Medo de quê? (Afraid of what?) and Encontrando Bianca (Finding Bianca). The first tells the story of a teenage boy who becomes interested in a male classmate and also shows scenes of aggression towards male homosexuals. The second is about the experiences of a teenager who is a transvestite.

The other three videos are Probabilidade (Probability), which is about a boy who is attracted to both boys and girls, Torpedo (Torpedo), which is about a couple who are both girls, and Boneca na mochila (Doll in the backpack), which portrays the anxieties of a mother who finds out that her son enjoys playing with dolls. All five videos have, as their main theme, respect for sexual diversity and the questioning of existing pre-conceptions relating to the LGBT population.Citation12

The materials from the project also covered many other topics, according to Lena Franco, one of the authors, including discussion of the imposition of the norm of heterosexuality and the history of the LGBT movement in Brazil and human rights, as well as issues of teenage pregnancy, love, masturbation, sexual and domestic violence, and prevention of sexually transmitted infections and HIV.Citation13

However, as a consequence of the pressures from the Evangelical Parliamentary Front of the National Congress, in May 2011 Brazil's president, Dilma Rousseff, cancelled the project. The Ministry of Health and Education was told to stop all activities on it, and the following statement was published in a well-known Brazilian newspaper: “After this Wednesday's meeting with delegates of the ‘religious faction’, the Federal Government has decided to suspend all materials dealing with the issue of homophobia which were being produced by the Ministry of Health and Education.”Citation14

Dilma Rousseff's decision was completely unexpected, particularly since at the beginning of that same month the Federal Supreme Court had unanimously approved five petitions for legal recognition of common law marriage of homosexual couples, and the Committee on Human Rights and Participative Legislation of the National Congress had voted in favour of a bill proposing changes in the Brazilian Civil Code that included recognition of same-sex unions.

Thus, paradoxically, a project to fight against homophobia and to help teachers to tackle it through sex education was suspended due to pressure from a homophobic political grouping.

The Brazilian Association of Lesbians, Gays, Bisexuals, Transvestites and Transgenders (ABGLT), along with other civil society organizations, such as the Brazilian Articulation of Lesbians (ABL) and the National Articulation of Transvestites and Transgenders (ANTRA), publicly criticized the decision and denounced the suspension of the project as a bargaining chip for other political negotiations. This was because the Evangelical Parliamentary Front had agreed not to support a petition to investigate the wealth of Antonio Palocci, the President's Chief of Staff, if the production of the materials for “School without Homophobia” was cancelled.Citation15

But this “bargain” is not the whole story. The contradictions involved expose the fact that sex education is a socially disputed space, where sexual identities and practices may be legitimated or discredited. In this sense, sex education itself, far more than specific topics such as teenage pregnancy and sexually transmitted infection prevention, is significant and acquires relevance because of the messages transmitted through it about sexual and gender identity, the consequences of inclusion vs. exclusion, acceptance vs. discrimination, and normality vs. aberration.

A number of organizations and groups have been interested in, watchful of and anxious about what is said, done and transmitted with respect to sexuality in schools, which is why it is important to question pedagogical practices that reinforce and legitimize inequalities and defend the school as a space of respect and inclusion.Citation16

It is in the context of these events that this paper reports on a study of the implementation of policy on sex education in the National Curriculum in the 56 state primary schools of Novo Hamburgo, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, based on interviews with 82 teachers working in those schools between January 2011 and April 2012. Of the 56 state primary schools, 49 were located in urban areas and seven in rural areas.

The city of Novo Hamburgo, with 240,000 inhabitants, is considered economically prosperous. It was founded in 1927 by German immigrants, similarly to many cities in southern Brazil, where German culture has remained highly influential and the German language is in the syllabus of several schools in the region. Religiosity has historically marked the city, with a great presence of evangelical and Catholic religions.

Methodology

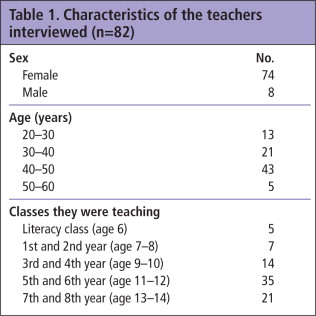

The 82 teachers interviewed represented approximately 30% of the teachers registered with the Human Resources Department of Novo Hamburgo's Town Hall. Table 1

summarises their characteristics. The criterion for selecting the teachers was their willingness to collaborate with the research. A summary of the project was circled among the teachers in each school in the first half of March 2011, asking any interested teachers to communicate their availability to the school board. The following week, a list with the names of the interested teachers was drawn up. The process of interview and analysis took place between April 2011 and early 2012.We combined quantitative and qualitative methodologies. The semi-structured interviews covered the teachers' understanding of sex education; interpretation of sex education as a cross-cutting theme; school subjects where sex education is brought in; and conceptions of gender and sexuality put forward in sex education. The interviews were recorded and transcribed by three interns who participated in the project.

Analysis of the interviews was carried out through the Técnica de Análise do Discurso do Sujeito Coletivo (Discourse Analysis Technique of the Collective Subject), created and validated in Brazil.Citation17 This technique enabled us to discover the composition of the discourse, question by question. First, all the answers to every question in the interview were identified. Next, similar answers were grouped and placed one after the other in a paragraph. Repeated statements were then eliminated, leaving differing answers which together formed a paragraph that articulated the views of all interviewees, comprising the collective discourse. Then the central idea that synthesised the core views of that group of answers was extracted, which reads as if it is just one person speaking who is expressing the ideas shared by the whole group.

The DCS technique also has a quantitative dimension, since it requires taking into account the quantitative representation of each collective discourse in relation to the total of respondents. Therefore, calculating percentages is important for determining the portion of interviewees who shared each collective discourse.

Findings: discourse analysis and discussion

What do you understand by sex education?

In response to the question of what the teachers understood by sex education, the core ideas of the collective discourse and the percentage of teachers who mentioned them were: talking about prevention and body care (73.2%), satisfying pupils' curiosity on sexuality (14.6%), and talking about moral concerns (12.2%).

Talking about prevention and body care was defined by the collective discourse as:

Sex education is talking about the body, its parts, how to protect it. Prevention of sexually transmitted infections. How to prevent teenage pregnancy. Explaining the contraceptive methods. Talking about menstruation, masturbation and reproduction. Talking about the importance of condoms. Also about the sexual act and reproductive organs.

Meaning of sex education as a cross-cutting theme

In response to the second question, about what it means to treat sex education as a cross-cutting theme, the core ideas mentioned were to: discuss it whenever pupils are interested (67.4%) and discuss it in each school subject (21.8%). The other 10.8% of teachers evaded the question. The collective discourse of the majority, discussing topics related to sexuality only when pupils showed interest, was as follows:

There is no rule; there is no need to decide ‘All right, now I'll teach sex education.’ You can't talk about things they are not curious about. A cross-cutting approach means that you don't have to teach the subject as institutionalised, each teacher will choose the right time to tackle sex education. I've never planned a time to discuss it; we discuss it when a question or doubt comes up. I bring the subject up according to the pupils' interests. It's a thorny issue and one should let sleeping dogs lie. You shouldn't anticipate their questions or talk more than necessary. But their questions can't go unanswered, no matter what their age or year is. With the youngest ones you tackle the issue if they ask, otherwise you don't. You cannot force it and you should always bear in mind their need to talk.

This discourse shifts educational responsibility, allowing the teaching staff to tell themselves that as long as pupils do not ask, sex education need not be talked about. This response may be closely related to censorship by pupils' families. 54% of the teachers interviewed said that on many occasions they had to deal with parents who disagreed with discussing sexuality at school and considered that talking about sex and relationships was solely the responsibility of the family. In the interviews we also learned that there had been complaints from parents in ten schools, questioning the sex education activities and arguing that explanations about the use of condoms could be considered pornographic.

Lack of training was another obstacle for further implementation of sex education. A total of 89.4% of the teachers said they found it difficult to tackle sex education and that they had no training in this area, which was also evidenced in another recent study on the subject, conducted in 2012 in Canoas, a city near Novo Hamburgo, with teachers working in primary state schools.Citation10

School subjects in which sex education is taught

We hoped that a cross-cutting approach to sex education would go beyond traditional approaches that place it within the sphere of science. However, this approach is still deeply rooted. When asked in which school subject sex education was taught, 51% of the responses mentioned science. The other core responses were: no specific subject (28.2%), physical education classes (9.4%), religion classes (7.1%) and Portuguese classes (4.3%).

The collective discourse that sex education is taught in science class said:

The science teacher works with specific subject matters from which (s)he discusses body care, prevention and pregnancy. Science teachers do a great job at teaching the reproductive system, sexually transmitted diseases and other facts about teenage pregnancy. Last year we discussed sexual relations. We studied the human body and all its parts and then we discussed reproduction, pregnancy, and sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Sex education is more explicit in biology, since it tackles health, diseases and reproductive organs. In science classes they study STIs and contraceptive methods. As girls begin to ask, the science teacher talks about menstruation, hormonal changes, pregnancy, and prevention.

Another relevant issue is that sexuality was discussed mainly from a reproductive angle and did not emphasize the means to prevent pregnancy. This could be a paradox in the sex education practices of these schools. As Altman points out: “There seems to be a contradiction... One of the objectives of sex education is avoiding teenage pregnancy… However, when sex is discussed, all the focus is precisely on fertilisation, pregnancy and motherhood.”Citation18

Conceptions of gender and sexuality

The focus of sex education

The last group of questions asked about teachers' conceptions of gender and sexuality. When we asked who was more the focus of sex education, boys or girls, the core responses were: both (76.6%), more emphasis on girls (17.8%), and more emphasis on boys (5.6%).

Although a majority of the teachers answered that it is targeted at both, it can nevertheless be seen that there are contradictions in the related collective discourse:

For everyone. For both. Girls do not do things alone. Sexuality is not only theirs, it is everybody's. It is as much for the boy as for the girl, but with the girl you have to deal with the issue of emotional ties, while it is different with boys, because they give more attention to the physical issue. Both need to protect themselves and girls need to know how to avoid pregnancy. Both need to know about the topic, it affects the girls, but they don't get pregnant alone, it is together with the boys and the girls need to pay attention. I think that sex education should happen in the same way for both, but pregnancy also needs to be discussed directly with the girls.

Nevertheless, some signs of change with regard to what an accepted model of masculinity might be can be identified in the collective discourse among those who said there was more emphasis on boys:

Mainly for the boys, especially here in the south of Brazil where we have this sort of mandatory “I am virile and a macho”. With the boys, because they don't take responsibility, get someone pregnant and then withdraw from their responsibility. With the boys, because they experience this testosterone burst and feel that the more girls they sleep with the better. With the boys, because the families are more used to controlling and protecting the girls, while the boys are free to do whatever they want. I think it is more for boys than for girls, because the girls have an idea, they will get pregnant, but the boys have no idea about being a father.

What do you consider abnormal?

In response to the question of what they considered abnormal in relation to sexuality, the discourses that emerged were as follows: sexual abuse (28.1%), homosexuality (23.2%), teenage pregnancy (14.6%), nothing is abnormal (9.8%), not revealing one's sexual orientation (8.5%), public homosexual manifestations (5.5%), zoophilia (5.5%), prostitution (2.4%), and transsexuality (2.4%).

Thus, for 25% of the teachers, homosexual relationships and transsexuality were considered abnormal, and almost 10% more were concerned about people revealing their sexual orientation. The teachers' collective discourse on homosexuality was as follows:

It bothers me very much seeing a man with another man or a woman with another woman, I can't help thinking it's not normal. I don't criticize nor mock homosexual relationships, as children and many adults do, but I don't find it normal. Homosexuality is abnormal, the Bible says that God created men and women to procreate. If I see a woman who likes women, I won't stop being her friend, but it seems wrong to me. If a woman is with another woman, it's her choice, but I don't agree that they show it off to other people, it's a matter of respect.

Really abnormal is two women or two men kissing publicly. This has to be only between them, in a non-public place. Abnormal is to be doing something in public, be explicit, show yourself too much and openly in front of everyone. It doesn't matter what I'm doing in my own home, but outside I have to respect the others around me. Abnormal is to live homosexuality publicly as if it was something normal.

Overall, these quite conservative views were expressed by a significant number of teachers, and were likely to influence their teaching on sex education. This result seems to be directly related to the age of the interviewed teachers, as 58.5% were aged between 40–60. In any case, these concerns help us to understand that although the biology of sex was thought to be the main point of sex education, some teachers also considered it a space to build and correct bodies, and to legitimise a heteronormative and traditional logic with regard to gender and sexuality. We recall a moment in the study that illustrates this well: one of the teachers said she noticed that a three-year-old boy needed sex education classes. This was because, she believed, he exhibited signs of homosexual orientation because he liked to go to the ladies toilet. The solution she found was to refer him to a psychologist for a corrective intervention.

On the other hand, more than one in four teachers thought sexual abuse was abnormal or wrong. This is a positive, gender-aware response, and we hope it too is influencing the content of sex education. The teachers' collective discourse on sexual abuse was as follows:

Rape, abuse and all kinds of sexual aggression are abnormal. Abnormal is when a person is forced to do something to another person, when violence or aggressive sexuality is part of the situation. Abnormal is when a child comes to school and says they were abused in the home of their father, uncle or grandfather. Attacking and injuring body and health is abnormal. Sexual abuse during childhood is abnormal, it is paedophilia.

Nothing is abnormal, it is important for everyone to have options, if this gives them pleasure, and if it makes them happy everything is fine. I don't think anything is abnormal; everyone has total freedom of choice when it comes to sexuality. There is nothing abnormal, because it is normal to do what you want with your body. It is normal to be able to be happy. Everything that the person chooses and that respects the options of others is normal. It is normal to take care of your needs whatever they may be.

Thus, we cannot ignore that schools are highly implicated in regulation and correction of the sexual and gender expressions of boys and girls, and that this is inseparable from the simultaneous production of hierarchies that legitimize and authorize exclusion, marginalization, subordination and violence between sex and gender identities, which poses an important political transcendence.

Conclusions and recommendations

As the teachers in this study constituted a third of all primary school teachers and were the ones willing to discuss these matters with us, we believe their perspectives can be said to represent what is happening in their schools, not just in their own classrooms. Their responses reveal that many of the primary schools in Novo Hamburgo have not incorporated sex education into their lessons as a cross-cutting theme. We therefore recommend far more discussion of how to implement what the National Curriculum outlines, in order to support all teachers to include appropriate information and activities within each of their subjects. We also propose the creation of experimental projects that explore alternatives such as having a fully trained sex educator in each school, who would coordinate all aspects of sex education. We would encourage that this should include the sharing of materials and resources among all the schools, and agreement on what should be taught.

Given the fact that many of the teachers felt poorly equipped to teach sex education, having never been trained to do so, we strongly urge that education degree courses in universities provide sex education training that will help teachers with both the theoretical and methodological issues of sex education. It is not only school children who need to learn about and understand sexuality, it is teachers and parents as well. In that regard, we call on Brazil's President to reverse her decision to close down the project on “School without Homophobia” and insist that the project be taken forward and implemented, and that she encourages further work to develop materials for schools on these issues, led by the Ministry of Health and Education.

The purpose of sex education also encompasses the possibility for teachers to re-educate themselves to act as sex educators at all school levels. An educator should be aware of his/her place in the change process so that our societies can be more just, considering the small changes that they might help to bring about.

The interest and commitment of teachers is crucial, but teachers cannot be expected to act individually to implement the National Curriculum. We recommend that the government directs the boards of educational institutions to take up sex education as a priority subject, which is included on the agenda of pedagogical meetings and which involves supervision, training and institutional control. Everything that is not requested, controlled and evaluated in schools is perceived to be secondary or unimportant and is not prioritised.

Finally, we suggest that each school carries out a study of local sexuality-related issues and problems – involving teenagers in identifying the issues and problems – and on the basis of the findings, each teacher presents a pedagogical proposal of how to integrate sex education into the subject they teach. This calls for being aware of the effects on teenagers of the normative underpinnings of the content of sex education, in order not to discredit or condemn sexual identities and practices that part with heteronormative standards. This will support teachers to become committed to comprehensive and inclusive education on sex, sexuality and relationships, and the democratization of schools.

Notes

* Primary school include first to ninth years, ages 6–14; high schools include tenth to twelfth years, ages 15–17.

References

- United Nations. Millennium Development Goals. 2011; UN: New York.

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Pesquisa Nacional de saúde do escolar. 2009; IBGE: Rio de Janeiro.

- Sasson E. Gravidez na adolescência: a cada 18 minutos, uma menina de 10 a 14 anos dá à luz uma criança, no Brasil. Rede Globo.com. 2 September 2009. Liga das Mulheres: 1. p. 1.

- R de Farias, COO Moré. Repercussões da gravidez em adolescentes de 10 a 14 anos em contexto de vulnerabilidade social. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica. 25(3): 2012; 596–604.

- Fundo das Nações Unidas para Infância. O direito de ser adolescente. 2011; UNICEF: Brasília.

- Programa das Nações Unidas para o Desenvolvimento. Informe de Acompanhamento Municipal dos Objetivos de Desenvolvimento do Milênio. 2009. www.portalodm.com.br/relatorios/5-melhorar-a-saude-das-gestantes/rs/novo-hamburgo#

- DR Quaresma da Silva. Mães-menininhas: a gravidez na adolescência. (PhD- Thesis). 2007; Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul: Porto Alegre.

- C Sperling. Sexo forever: Corpo, sexualidade e gênero nos grafitos de banheiro em uma escola pública de Porto Alegre. (Thesis Postgraduate Programme). 2011; Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul: Porto Alegre.

- Ministério de Educação e Cultura (Brasil). Parâmetros Curriculares Nacionais. 1997; MEC: Brasília, 311–312.

- DR Quaresma da Silva, D Fanfa Sarmento, P Fossatti. Género y sexualidad: ¿Qué dicen las profesoras de Educación Infantil de Canoas, Brasil?. Education Policy Analysis Archives. 20(16): 2012; 1–20.

- Ministério da Saúde (Brasil)/Conselho Nacional de Combate à Discriminação. Brasil sem homofobia. 2004; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília. http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/brasil_sem_homofobia.pdf

- N Leão. Veja vídeos do kit anti-homofobia do MEC. Último Segundo. 19 May 2011. Educação: 1. http://ultimosegundo.ig.com.br/educacao/veja+videos+do+kit+antihomofobia+do+mec/n1596964952707.html

- C Roman. Movimento gay reage a suspensão de kit anti-homofobia. Carta Capital. 27 May 2011. Sociedade: 1. www.cartacapital.com.br/sociedade/movimento-gay-reage-a-suspensao-de-kit-anti-homofobia/

- Zero Hora. Após pressão de religiosos, Dilma suspende produção de kit antihomofobia. 25 May 2011. Geral: 1. p. 1.

- O Globo. ABGLT lamenta suspensão do “kit anti-homofobia”. 26 May 2011. Política: 1. http://oglobo.globo.com/politica/abglt-lamenta-suspensao-do-kit-anti-homofobia-diz-que-mec-acompanhou-desenvolvimento-do-material-2764470

- D Quaresma da Silva. La producción de lo normal y lo anormal: un estudio sobre creencias de género y sexualidad. Subjetividad y Procesos Cognitivos. 16(1): 2012; 178–199.

- F Lefêvre, AMC Lefêvre. O discurso do sujeito coletivo. 2003; Educs: Caxias do Sul.

- H Altmann. Educação sexual em uma escola: da reprodução à prevenção. Cadernos de Pesquisa. 39(136): 2009; 175–200.

- R Connel. Masculinidades. 2003; Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: México DF.