Abstract

Unwed pregnancy among adolescents is a disturbing event in Indian belief-systems, and very young motherhood limits girls' social, economic and educational prospects. Girls who seek abortions are always at higher risk for delay in care seeking; this paper looks at the reasons why. It reports the experiences of 34 unmarried adolescent girls and young women, aged 10–24 years, who obtained induced abortion from a tertiary care abortion clinic over a period of seven months in 2004. Ten were below 19 years of age, the rest were 20–24 years. Only eight of the 34 pregnancies were <12 weeks. The reasons for delay were fear of disclosure, lack of any support system and scarcity of resources. In 30 cases, the decision to terminate was made jointly with family members, especially the mother. Only half knew about contraception, of whom two used condoms. Only two of the partners accompanied the girl to the abortion clinic and another two offered some financial support. Because of the conflict between wanting to have sex and feeling guilty about it, these young people experienced terrible distress in the course of unwanted pregnancy. Comparing the adolescents who attended the clinic in 2004 with those we have seen in 2012–2013, the paper shows that as regards the essentials, much has remained the same.

Résumé

Les grossesses chez les adolescentes célibataires sont un événement troublant dans les systèmes de croyance indiens et la maternité chez les très jeunes femmes limite leurs perspectives sociales, économiques et éducatives. Les adolescentes qui souhaitent avorter courent toujours plus de risques de morbidité et de retard dans la recherche de soins car elles tendent à se faire soigner par des prestataires non formés ou non agréés. L'article décrit l'expérience de 34 adolescentes et jeunes femmes célibataires âgées de 10 à 24 ans, qui ont interrompu leur grossesse dans un centre d'avortement de soins tertiaires sur une période de sept mois en 2004. Dix étaient âgées de moins de 19 ans, les autres avaient de 20 à 24 ans. Seules huit des 34 grossesses étaient <12 semaines ; les raisons du retard étaient la peur de la révélation, le manque de tout système de soutien et la pénurie de ressources. Dans 30 cas, la décision d'avorter avait été prise conjointement avec les membres de la famille, spécialement la mère. La moitié seulement des femmes connaissait la contraception, et deux utilisaient des préservatifs. Seuls deux des partenaires avaient accompagné la jeune femme dans le centre d'avortement et deux autres avaient offert un soutien financier. En raison du conflit entre la volonté d'avoir des rapports sexuels et le sentiment de culpabilité, ces jeunes connaissaient une terrible détresse au cours de leur grossesse non désirée. Comparant les adolescentes qui ont fréquenté le dispensaire en 2004 avec celles que nous avons vues en 2012–2013, l'article montre qu'en ce qui concerne les points essentiels, la situation n'a guère changé.

Resumen

El embarazo entre adolescentes solteras es un suceso preocupante en los sistemas de creencias indias; la maternidad a una edad muy temprana limita las posibilidades sociales, económicas y educativas de las niñas. Aquéllas que buscan servicios de aborto siempre corren mayor riesgo de postergar la búsqueda de servicios y de morbilidad porque tienden a acudir a prestadores de servicios no capacitados o no autorizados. En este artículo se informan las experiencias de 34 adolescentes y jóvenes solteras, de 10 a 24 años de edad, que recibieron servicios de aborto inducido en una clínica terciaria de aborto, en un plazo de siete meses durante el 2004. Diez de ellas tenían menos de 19 años; el resto, de 20 a 24 años. Solo ocho de los 34 embarazos eran <12 semanas; las razones para postergar la búsqueda de servicios fueron: temor de revelación, falta de un sistema de apoyo y escasez de recursos. En 30 casos, la decisión de interrumpir el embarazo se tomó conjuntamente con miembros de la familia, en particular la madre. Solo la mitad tenía conocimiento de la anticoncepción; dos de ellas usaban condones. Solo dos de las parejas acompañaron a la adolescente a la clínica de aborto y otros dos ofrecieron algún apoyo financiero. Debido al conflicto entre querer tener sexo y sentirse culpable al respecto, estas jóvenes se sintieron muy afligidas durante su embarazo no deseado. Al comparar a las adolescentes que acudieron a la clínica en 2004 con las que vimos en 2012–2013, el artículo muestra que no han cambiado mucho la situación en cuanto a los puntos esenciales.

Given Indian culture and belief systems, unwed pregnancy among adolescents is a disturbing experience not only for the individual but also the entire family. The psychological and social brunt of the pregnancy stretches right through the life span of the affected adolescent, in addition to any immediate health-related problems consequent to pregnancy at a young age. Adolescent girls and other young women in society are the most vulnerable in these situations; in the majority of cases male family members are hardly ever informed about the pregnancy.

More than half of pregnant adolescent girls seek abortion care as late as the second trimester or even third trimester of their pregnancies. A 2001 study from the North Indian states reports that 56% of the adolescent girls were more likely to seek abortion at unauthorized settings.Citation1 A 2002 study similarly found that unmarried girls are likely to delay in seeking care because of the lack of support from family and society, the cost of care, confidentiality issues, and condemnatory attitudes of health care providers. Often single girls are forced to pay high fees for abortion services.Citation2 Thus, unintended pregnancy among unmarried adolescents is a public health problem.

This study aimed to identify the reasons that cause delay for adolescents and young women (aged 10–24 years) in seeking safe abortion services and their perceptions regarding abortion. Although the findings are from 2004, the paper will show that much has not changed in 2013.

Methodology

The study was done at the Government Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, a tertiary care hospital. Abortion services in the medical colleges are provided through the Family Welfare Clinic (FWC) attached to the Gynaecology Department. Abortion care, contraceptive services and post-natal care are provided at this clinic. High-risk cases and second trimester abortions are usually referred to tertiary care institutions for management. The institution caters to all sections of society but, since the services are free of cost, those who can't afford to pay invariably approach this facility. Though the tertiary care centre is located in an urban area, many from rural areas prefer it for reasons of privacy and confidentiality.

A cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted among abortion seekers attending FWC. The sample selected for this study included adolescents and young women (10–24 years) who were unmarried. During the seven months of data collection, from June 2004 to December 2004, the FWC registered 593 girls and young women aged 10–24 who approached the clinic for termination of pregnancy. This included 559 who were married and 34 who were not. Of the 559 who were married, 526 came in the first trimester and 33 in the second trimester. Of the 34 who were unmarried, 8 came during the first trimester and 26 in the second trimester of their pregnancies.

This paper is about the 34 unmarried young people. After Institutional Ethics Committee clearance was obtained from the hospital and getting informed consent in local language, all 34 unmarried women were interviewed by the author with a pre-tested structured interview schedule. Interviews were in the local language and quotes from answers to open-ended questions were translated into English with the help of a translator. Data were cleaned and quantitative measures were used for close-ended questions. The responses for open-ended questions were freelisted to get the range of responses. Domains were evolved on the basis of responses that conveyed similar ideas. Apart from socio-demographic details the study variables included reasons for delay in termination of pregnancy. Before the start of the study a pilot study was done with ten subjects to pretest the interview schedule and gauge the pattern of behaviour in seeking abortion care, such as what was the routine time needed to suspect a pregnancy, how easily was the pregnancy confirmed, how long did it take to decide to terminate it, how soon did they approach the health care facility and within how many days thereafter were they able to avail abortion services.

From the pilot study data, the period of delay was broken down into five stages, from detection of pregnancy until its termination. These stages were delays in 1) noticing the pregnancy, 2) confirming the pregnancy, 3) making the decision to terminate, 4) accessing the health care system for abortion services, and 5) delay due to the functioning of the health care system. Questions were designed to elicit information about what happened during each of these steps and understand the perceptions of these girls and young women regarding abortion, what they felt about having an abortion and so on.

In-depth case studies to strengthen the primary data emerged from the interviews. The respondents selected for case studies were those who had experienced delay before getting an abortion.

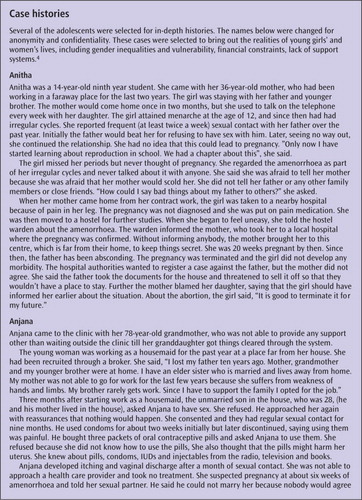

Who were these unmarried young pregnant women

Of the 34 subjects, one was just 14 years old and was 20 weeks pregnant and nine were aged 15–18. The other 24 were 19–24 years old. Seventeen were Hindu, 11 were Christian and 6 were Muslims. Nine had primary/middle school education, 17 had high school education, and 8 had college education. Occupation-wise, 13 were engaged in their own household work, 9 were working as housemaids in other houses, 8 were students, 3 had no specific job and had mental health problems or psychiatric illness, and 1 was a skilled worker.

Only 16 of the 34 knew about some contraceptives, mostly condoms and oral pills. Only two women's sexual partners had used condoms, and that too irregularly. Most women said they never talked about contraception in their relationship. Inadequate knowledge and inability to talk with their partners played a major role.

“We never talked about pregnancy or contraception. It [sexual contact] all happened unexpectedly all the time. And we have never planned it.”

Decision-making on termination and sources of support

Many of the adolescents, 29 of the 34, knew that sex can lead to pregnancy. Two did not respond to this question and the remaining three said they were not aware that the sexual activity they engaged in would lead to pregnancy. One of the three was the 14-year-old, and the other two were under 19. In 26 cases, the pregnancy was first doubted by the adolescents themselves and in the other eight cases, others whom they confided in first doubted they were pregnant, and only later was it confirmed. Four had a history of previous termination of pregnancy.

In 29 cases, the decision to terminate was made jointly by the adolescent with a family member, especially their mother. In five cases, the decision to terminate was made by the adolescents themselves.

Most of the adolescents said their sexual partners knew about the pregnancy. Only a few involved their sexual partners in taking the decision on termination. Most of them were accompanied by their mother and very few by another relative. Only in two cases did the sexual partner concerned accompany the girl to the clinic and only in another two cases did the partner offer some financial support for the abortion.

Although their knowledge of how pregnancy occurs and how pregnancy is detected was fairly good, to make a decision on termination they needed the support of other family members. The delay in communicating with other family members about the pregnancy was a high risk. Therefore the immediate support of the family which the adolescent can avail and strengthening of the relationships and communication within the family structure are both important.

Who they got pregnant with

Twenty-six adolescents reported that they knew who they got pregnant with and had a consensual relationship with them. Six reported they knew the partner but were coerced into sex. Two of these six said they were raped and four said initially they were forced and later blackmailed by the partner saying he would disclose to others. The remaining two reported that the person responsible for the pregnancy was unknown to them, and that they had been raped. Of those who knew their partner, 14 said he was a neighbour and 7 said it was a relative, mostly brothers-in-law. Five reported that a workplace senior person was responsible for the pregnancy.

Sixteen said they had been in the sexual relationship for more than a year. Another 14 reported less than a year and 4 reported a single contact. Nearly 17 offered no particular reason for continuing the sexual relationship while 9 said they continued the relationship because of promises of marriage given to them by the partner. Four reported that the man was blackmailing them to continue the relationship.

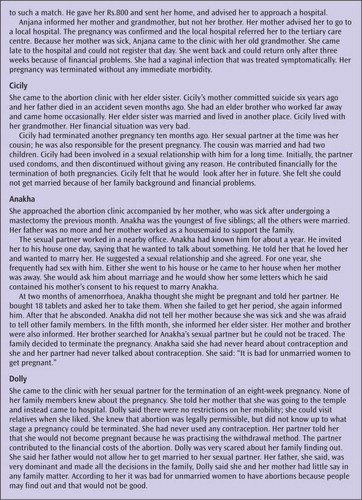

Many of these young women were highly vulnerable to exploitation; their experiences suggest an alarming rate of exploitation of adolescent girls. The 14-year-old, a ninth year student, described how she had sought an abortion at 20 weeks of pregnancy following more than a year of sexual abuse by her father:

“My father used to beat me for not consenting to his wishes initially and I had no other alternative, but gradually I began to co-operate.”

“I developed discharge and pain in my abdomen for which I took no treatment. When I became pregnant he gave me Rs.800 and sent me back home.”

Knowledge of abortion and delays in obtaining abortion care

Approximately half the adolescents had no knowledge of the stage in pregnancy up to which termination was possible. All eight adolescents who came for a termination in the first trimester had no delay at any stage. Of the 26 who came for a second trimester abortion many had delays at more than one stage: 24 had a delay in suspecting pregnancy and 20 in confirming the pregnancy. Only two of the 26 were delayed in decision-making on termination of pregnancy. The decision to terminate was fast, probably due to the unacceptability of an unwed pregnancy. Ten met delays in accessing the clinic and another eight experienced delays within the health care system. The reasons for these delays are described below.

Delay in suspecting pregnancy

Many of the women reported an existing irregularity in their menstrual cycle as the reason for delay in suspecting pregnancy. Approximately half never thought they might be pregnant although they were not menstruating.

“I thought one or two sexual contacts would not lead to pregnancy.” (18-year-old)

“I told my relative about the lack of menstruation. They said it is common at this young age and nothing needed to be done.” (17-year-old)

Delay in confirming pregnancy

The major reason for delay in confirming the pregnancy was due to fear of talking with members of the family.

“My mother would scold me if I told her. My mother is sick and the concerned person (sexual partner) is not to be seen. I was afraid this would make my mother's condition worse.” (21-year-old)

Delay in accessing the clinic

Only eight of the 34 approached the clinic for termination in the first trimester of pregnancy. A majority gave family-related problems as the reason for the delay in accessing the health care system.

“I told my mother about my pregnancy. She was afraid to talk to my father. Then my brother met with an accident and mother had to go with him. Nobody was there to care for me.” (20-year-old)

“We consulted a private hospital. They said since the pregnancy is advanced it could be terminated only in a medical college. We thought this would need a lot of money. It took some time for us to arrange the money.”

Delay within the clinic

A majority quoted problems such as health care workers insisting that they arrange for supplies of blood, or ultrasonography, which was considered mandatory before second trimester abortion to confirm the period of gestation and any problems. These could not immediately be done. Another problem mentioned was that it is routine to insist on a female companion in case the patient needs support. It is unlikely that without this, they would be admitted for termination, and this was one of the reasons given for delay. Financial problems were another reason for delay at this stage too.

“The manager at my work place raped me. I approached the clinic after missing two periods. I was told I would have to pay Rs.1000 to the doctor to terminate the pregnancy. I am the only earning member in my family. Since I did not have that money I took a loan after surrendering my gold earrings. By that time pregnancy had advanced to second trimester.” (23-year-old)

Perceptions of induced abortion

Most (27) of the adolescents believed that abortion was a sin with the possibility of long-term psychological impact.

“It is a grave sin in my religion. Now I feel guilty for what I have done. If I were aware that this would end up in pregnancy I would never have gone with that person.” (19-year-old)

Is anything different today?

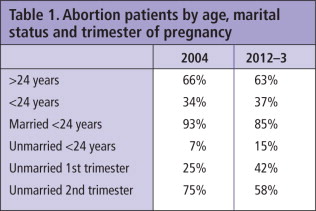

I am still working in the same clinic at this writing, and since 2004 several changes have occurred. First, surgical abortion has been replaced almost entirely by medical abortion, and is women's preferred method. Second, there are fewer abortion seekers attending the tertiary clinic overall, because hospital policy limits us to attending only referral cases. However, among those who do attend, the proportions by age are similar, and there are more unmarried young women under age 24 than in the past, but the biggest change is that the proportion seeking second trimester abortions, though still 6 out of 10, has fallen considerably (Table 1

).Compared to 2004, none of the following issues among young, unmarried abortion seekers had changed in 2012-13: knowledge of contraceptives, use of a reversible method, knowledge of abortion, type of sexual partner, lack of any support system. Yesterday, for example, when I was collecting the most recent data on abortion seekers, a 12-year-old girl came in with an eight-week pregnancy along with her mother. She reported more than a year of sexual relationship with a relative. Then, a post-graduate MD gynaecology student, who was posted in the Family Welfare Clinic for one month to look after all the cases, mentioned to me that in the first four days of her posting, four unmarried girls came in seeking abortions, of whom three were in the second trimester.

Conclusions

Sexual relationships among adolescents and young adults in India are a reality that needs to be addressed effectively. Findings show that nearly three-fourths of the young women were having a consensual relationship with a known partner for quite a long duration. Moreover, four of them experienced rape and another four pressure/coercion to have sex by employers and family members. Exposure to and adequate skills training in family life education need to be strengthened, for both girls and boys. Adolescents and young women should be empowered to say “no” when the situation warrants it. Abstinence during adolescence should be encouraged and its merits highlighted. Those having sexual relationships need access to and information about contraceptives and condoms. Sexual abuse and coercion are a reality that needs to be confronted by society, families and the government.

The legal age of marriage for girls in Kerala is 18 years and even before this study the mean age at marriage was 21 years, according to the National Family Health Survey-2.Citation3 In spite of this, many adolescents are at risk of pregnancy before the age of 18, and when they become pregnant, they are at high risk for delay in abortion seeking.

Though the state of Kerala claims it has high health standards, early health care seeking and high literacy,Citation5 these positive achievements do not count in the case of abortion. These social indicators should take into consideration sensitive issues such as abortion, to get proper interventions and policy level changes to reduce delays.

However, it is the life situations of adolescent girls and young women that show the underlying reasons for delays. Adolescents should be helped to remain in school through school policy and receive proper career counselling if they drop out. Family life education must be strengthened. Adolescent clinics which are presently functioning in secondary and tertiary care institutions need to be strengthened to eliminate stigma attached to abortion, and should be made more adolescent-friendly to provide counselling, condoms and contraceptives,Citation6 and to address specific issues raised by adolescents.

We now have a separate facility for counselling to take care of privacy and confidentiality. This will help young women to talk openly about their problems. Counselling on contraception is also now given to all abortion seekers, who are encouraged to avail the contraceptive services free of cost or given a prescription to get them from outside. The author is now one of the resource persons for the adolescent reproductive health programme going on as part of pre-marital counselling for school and college students. Half-day classes are conducted on reproductive health for selected schools and colleges, where the issues of pregnancy, abortion, contraception and related matters are discussed.

Acknowledgements

I am greatly indebted to all the young women who agreed to participate in the study without hesitation. This article is part of the project supported under the Small Grants Programme on Gender and Social Issues in Reproductive Health of the Ford Foundation. I acknowledge the great contribution of Dr Sundari Ravindran, coordinator of the project, Dr Sunita Bandewar, reviewer of the project, and Dr Mala Ramanathan, mid-term evaluator of the project, for their specific comments and suggestions throughout this project. My very sincere thanks to Dr TN Rajalekshmi, and Dr PB Sulekha Devi, retired Professor and Head of Department, Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Dr Rema Devi, retired Associate Professor, Community Medicine, and Mr Babu, Associate Professor of Statistics, Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram, for all their help.

References

- S Trika. Abortion scenario of adolescents in a north Indian city: evidence from a recent study. Indian Journal of Community Medicine. 26(1): 2001; 48–55.

- B Ganatra, S Hirve. Induced abortion among adolescents in rural Maharashtra. Reproductive Health Matters. 10(19): 2002; 76–85.

- International Institute for Population Sciences. National Family Health Survey 1998–1999. 2000; IIPS: Mumbai.

- TKS Ravindran, US Mishra. What information do we need for understanding gender–based inequalities in health? Paper presented at WHO meeting on Gender Analysis for Health. June. 2000; WHO: Geneva.

- Population policy for Kerala (undated). www.old.kerala.gov.in/dept_health/srcell/introduction.pdf

- S Pachauri, KG Santhya. Contraceptive behaviour among adolescents in Asia: issues and challenges. S Bott. Adolescents, Sexual and Reproductive Health: Evidence and Programme Implications for South Asia. 2002; World Health Organization: Geneva.