Abstract

In response to abstinence-only programmes in the United States that promote myths and misconceptions about sexuality and sexual behaviour, the comprehensive sexuality education community has been sidetracked from improving the sexuality education available in US schools for almost two decades now. Much work is still needed to move beyond fear-based approaches and the one-way communication of information that many programmes still use. Starting in 2008 Planned Parenthood Los Angeles developed and launched a teen-centred sexuality education programme based on critical thinking, human rights, gender equality, and access to health care that is founded on a theory of change that recognises the complex relationship between the individual and broader environment of cultural norms, socio-economic inequalities, health disparities, legal and institutional factors. The Sexuality Education Initiative is comprised of a 12-session classroom sexuality education curriculum for ninth grade students; workshops for parents; a peer advocacy training programme; and access to sexual health services. This paper describes that experience and presents the rights-based framework that was used, which seeks to improve the learning experience of students, strengthen the capacity of schools, teachers and parents to help teenagers manage their sexuality effectively and understand that they have the right to health care, education, protection, dignity and privacy.

Résumé

Suite aux programmes uniquement fondés sur l'abstinence aux États-Unis, qui encouragent des mythes et idées fausses sur la sexualité et le comportement sexuel, la communauté de l'éducation sexuelle globale a été écartée de l'amélioration de l'éducation sexuelle disponible dans les écoles américaines depuis près de vingt ans. Il reste encore beaucoup à faire pour dépasser les approches dictées par la peur et la communication à sens unique des informations que beaucoup de programmes utilisent encore. Depuis 2008, Planned Parenthood Los Angeles a élaboré et lancé un programme d'éducation sexuelle des adolescents, basé sur la pensée critique, les droits de l'homme, l'égalité entre les sexes et l'accès aux soins de santé. Ce programme repose sur une théorie du changement qui reconnaît les relations complexes entre les individus et les normes culturelles, le statut socio-économique, les disparités sanitaires et les facteurs juridiques et institutionnels. L'initiative d'éducation à la sexualité consiste en un programme de 12 séances pour les élèves de neuvième année, un atelier pour les parents, un programme de formation des pairs au plaidoyer et l'accès aux services de santé sexuelle. L'article décrit le développement et l'évaluation de cette initiative, et le cadre de droits ayant été utilisé, qui cherche à améliorer l'apprentissage, renforcer les capacités des écoles, des enseignants et des parents à aider les adolescents à prendre efficacement en charge leur sexualité et comprendre qu'ils ont droit à des soins de santé, une éducation, des informations et une protection, dans la dignité et la confidentialité.

Resumen

En respuesta a los programas de abstinencia exclusiva de Estados Unidos que promueven mitos e ideas erróneas sobre la sexualidad y el comportamiento sexual, la comunidad de educación sexual integral se ha descarrilado de mejorar la educación sexual disponible en escuelas estadounidenses durante casi dos décadas. Aún falta mucho trabajo por hacer para trascender los enfoques basados en temor y la comunicación unidireccional de información que continúan utilizando muchos programas. Comenzando en 2008, Planned Parenthood Los Angeles creó y puso en marcha un programa de educación sexual centrado en adolescentes y basado en pensamiento crítico, derechos humanos, igualdad de género y acceso a servicios de salud, fundado en una teoría de cambio que reconoce la compleja relación entre cada persona y las normas culturales, condición socioeconómica, disparidades de salud y factores jurídicos e institucionales. La Iniciativa de educación sexual consiste en un currículo de 12 sesiones de educación sexual para estudiantes de noveno grado; talleres para sus padres; un programa de capacitación de pares en promoción y defensa; y acceso a servicios de salud sexual. En este artículo se describe cómo se elaboró esta iniciativa y cómo se está evaluando, así como el marco utilizado, basado en los derechos, cuya finalidad es mejorar la experiencia de aprendizaje, fortalecer la capacidad de las escuelas, maestros y padres para ayudar a la adolescencia a manejar su sexualidad con eficacia y a entender que tienen derecho a servicios de salud, educación, información, protección, dignidad y privacidad.

Between 1996 and 2010, the United States government spent over one billion dollars supporting abstinence-only-until-marriage programmes.Citation1 In that period, the community supporting comprehensive sexuality education in the United States has been deeply involved in efforts to prevent the advance of these programmes because they promote myths and misconceptions about sexuality and sexual behaviour. While these efforts have had some success in exposing the lack of effectiveness of abstinence-only programmes in reducing unintended teen pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections, many researchers, advocates and educators were sidetracked from their primary focus on improving the sexuality education available in US schools. Much work is still needed to move beyond fear-based approaches and the one-way communication that many programmes still use.

Later, millions of dollars have been spent in research to prove the effectiveness of comprehensive sexuality education. Many advocates, such as the Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS), Answer, Sex Ed, honestly, Advocates for Youth, the National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy, and Planned Parenthood, have played a vital role in this work. SIECUS's advocacy work, for example, has focused on protecting young people's right to sexuality education by working closely with policymakers and collaborating with key partners. These efforts led to the introduction in 2011 of a bill to repeal ineffective and incomplete abstinence-only programme funding (S.578, H.R.1085), which would allow for the transfer of US$75 million in federal funds to the Personal Responsibility Education Program, which supports prevention of teen pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases. More recently, policy makers introduced the Real Education for Healthy Youth Act, which recognizes for the first time in federal legislation young people's right to sexual health information. Both very promising political developments. After two decades of valuable resources being used to assess who should be responsible for teaching sexuality to teens, and when and where such education should happen, it is refreshing to see a shift in the debate even though this bill has not yet been passed.

Of the approximately 750,000 teen pregnancies that occur each year in the US, 82% are unintended. In the last two decades, however, improvements in contraceptive use have led to a decline in pregnancy rates from 117 pregnancies per 1,000 women aged 15–19 in 1990 to 68 per 1,000 in 2008.Citation2 The majority (86%) of this decline was due to contraceptive use, and 14% to decreased sexual activity.Citation3 The 2008 teenage abortion rate was 17.8 abortions per 1,000 women, or 59% lower than at its peak in 1988.Citation2

Yet, teenage pregnancy is still the leading cause of high school drop-out among teenage girls. Less than half of teens who give birth before the age of 18 ever graduate from high school, and less than 2% graduate from college. Furthermore, young women and men who become parents experience lower educational attainment, greater financial hardship, and less stable marriage patterns. For young fathers, parenting is more likely to lead to economic and employment difficulties and to more economic hardships than among men who become fathers as adults.Citation4

Four articles in the American Journal of Sexuality Education in 2012 reflect new trends in the field: the need for school-based sexuality education,Citation5 inclusion of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBT) themes,Citation6 the power of using film clips to teach teen pregnancy prevention,Citation7 and an analysis of the portrayal of gender and sexuality in the media.Citation8 Most researchers, educators and health professionals now seem to agree that when it comes to promoting healthy sexual behaviours, information alone no longer suffices. Instead, it is argued that “sexuality education policies and programmes must be based in human rights and respond to the interests, needs and experiences of young people themselves”.Citation9 Addressing social messages, and understanding the complexity of the dynamics between gender identity, gender norms and sexuality have appeared as effective 21st century programme components.

The purpose of this paper is to share the experience of Planned Parenthood Los Angeles (PPLA) in testing the effectiveness of a rights-based approach to sexuality education, using best practices, and to show how and why this approach strengthens the capacity of schools, teachers and parents to help young people manage and enjoy their sexuality responsibly.

Comprehensive sexuality education in California since 2004

In 2004, the California state legislature enacted a law to guide schools on the provision of comprehensive sexual health education. The California Comprehensive Sexual Health and HIV/AIDS Prevention Act (SB 71), replaced a patchwork of confusing and often contradictory statutes on sexuality education with a clear and comprehensive new law with two purposes:

| • | To provide pupils with the knowledge and skills necessary to protect their sexual and reproductive health from unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections; and | ||||

| • | To encourage pupils to develop healthy attitudes concerning adolescent growth and development, body image, gender roles, sexual orientation, dating, marriage, and family. | ||||

The law says California public schools may offer sexuality education to students in fifth, seventh and ninth grades, but if they do so, it must be comprehensive. Many schools do not provide sex education because the law does not mandate it; What the law says is that schools that choose to provide sexuality education must comply with the requirements of the law and must notify parents about it, with an opt-out clause. Still, according to a 2010 report, the 50% decrease in the teen birth rate that California experienced between 1991 and 2008, from 70.9 per 1,000 in 1991 to 32.1 per 1,000 in 2009, can be attributed in large part to the substantial investment in teen pregnancy prevention education, programmes, and services in California.Citation10 Other reasons identified by research for the drop in teen birth rates are expanded access to contraceptive services, laws and policies that facilitate access to contraceptive information and care, and investment by private foundations in unintended teen pregnancy prevention.

“California – the only state that never accepted federal abstinence-only dollars – has made teen pregnancy prevention a high public policy priority, with a strong emphasis on comprehensive sexuality education and access to information and health care services teens need to prevent pregnancy and protect their health.” Citation11

The “Responsible Choices” curriculum: comprehensive but not enough

The Los Angeles Unified School District, the second largest in the country, with approximately 770,000 students, of which more than 400,000 are in high school, has adopted SB 71 and requires schools to offer HIV prevention classes. Planned Parenthood LA has been an approved provider of sexuality education to the LA school district for 18 years, and in that time has served more than 80 middle and high schools each year using a structured “speakers bureau” model, by which college students and volunteers are trained to teach sexuality education using a six-session curriculum called “Responsible Choices”. While the “Responsible Choices” curriculum is science-based and comprehensive, the methodology employed was less engaging and more centred on giving information. The main topics were: expressing sexuality, healthy relationships (mostly focused on heterosexual relationships and assertive communication), healthy bodies (anatomy), teen pregnancy, STIs and birth control. “Responsible Choices”, like many sexuality education programmes, believed that information is powerful, and that once teens had information, they would act on it to protect themselves from health risks. Its major limitation was the assumption that accurate information was sufficient to change behaviour, and therefore little attention was placed on the influence of the broader cultural and social context in which teens were making sexuality-related decisions.

Although comprehensive sexuality education programmes may at least be available in California, in our experience many comprehensive programmes have not moved beyond fear-based approaches (showing students pictures of STIs) and one-way communication (informing students about condoms and contraceptives).

Our own programmes also suffered from some of these flaws until 2008 when PPLA worked closely with Roosevelt High School to offer the “Responsible Choices” curriculum, weekly after-school peer training, sporadic parent education, and reproductive health care at the school-based clinic once a week. The experience was eye-opening, and the results, while by no means scientific, were inspiring. Pregnancy tests recorded by the school nurse pre- and post-12 months of the intervention, saw a sharp drop in positive pregnancy tests from 32 to 3 between April–June 2008 and 2009. In addition, the nurse noticed that students were coming to the clinic because they had heard about the sexual health services available in their peer advocacy groups. These results prompted the school to extend provision of sexual health services on campus, including pregnancy and STI testing and counselling, condoms and birth control, to five days a week.

This experience led us to discuss how to change from a programme focused primarily on reducing risk of adverse health outcomes to one enabling teens to feel confident in their ability to negotiate an intimate relationship safely.

We knew that six hours of classroom sexuality education, once during middle school and once during high school, wasn't enough to prepare students to engage in respectful intimate relationships, stay healthy and achieve their reproductive intentions. We also realized that interventions with students, parents, and school-wide should be based on the same curriculum and approach to promoting synergies and fostering opportunities for conversations about sexual health at school and at home.

We looked at dozens of effective programmes used in the United States and internationally and at studies that addressed young people's sexual health and well-being more holistically.Citation9 Why reinvent the wheel? To the extent possible, we would gladly have adopted an existing programme. Instead, we settled on combining best practices from the field and created a new curriculum that would resonate with Los Angeles' diverse youth population, could be adopted by state schools, and was consistent with SB 71.

The Sexuality Education Initiative for Los Angeles: building on best practices

The initiative was envisioned as a dynamic partnership between teens who know and understand their rights and trusted adults and institutions that have the capacity to protect teens' rights and deliver on their obligations to teens. This represented a critical shift in how to connect with youth because it recognized their right to learn, to be healthy and to have access to services. It also spells out the responsibilities of “duty bearers”Citation14 (usually institutions) to respect, protect and guarantee teens' rights to information, education, health care and protection. From this perspective, learning occurs as an intentional exercise that enables the learner to be capable of claiming their right to sexual health care by, for example, providing a safe environment, unbiased information, protection against abuse, and confidentiality in schools and in health care settings.

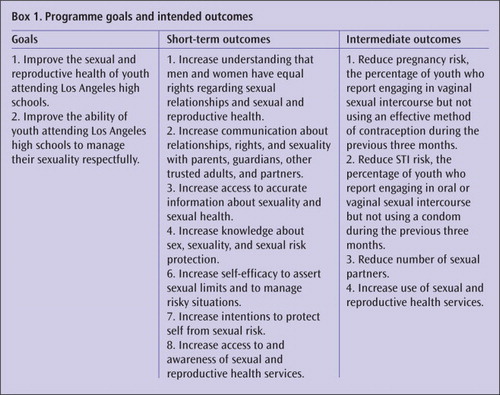

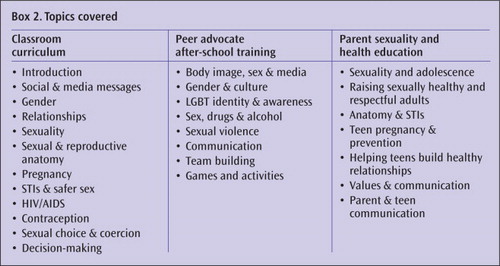

The Initiative is comprised of four components: a classroom sexuality education curriculum with 12 sessions for ninth grade students; workshops for parents; a peer advocacy programme; and access to reproductive and sexual health care. The goals and intended outcomes of the programme are summarised in Box 1

The topics covered in the 12 sessions of the classroom curriculum, eight additional topics offered to students who join the peer advocate training in an after-school club, and seven topics offered to parents in weekly gatherings on evenings or weekends are summarised in Box 2

Each component includes lesson plans and activities.

The four key concepts that served as pillars of the Initiative are:

| • | Evidence-based as defined in The Future of Sex Education Citation15 by SIECUS, Answer, and Advocates for Youth, which builds on the 3Rs approach (rights, respect, responsibility), used in Western Europe and disseminated in the United States by Advocates for Youth. | ||||

| • | Gender aware addressing the gender power dynamics that impact teens, particularly girls' ability to be assertive on sexual matters, and emphasizing the rights of youth to manage their own sexuality. Of particular interest was the pioneer work of the Population Council, It's All One Curriculum, which articulates gender and rights concepts and connects them to on-the-ground experiences such as the empowerment work of the Girls' Power Initiative in Nigeria, that uses critical thinking about gender roles and sexuality with teenage girls. It's All One includes a set of guidelines and activities for a unified approach to sexuality, gender, HIV, and human rights education (www.popcouncil.org/publications/books/2010_ItsAllOne.asp). | ||||

| • | Contextualized based on a theory of change that ponders the complex social context that emits multiple messages about gender roles and expectations influencing sexual behaviour. The Social Ecological ModelCitation16 developed by Bronfenbrenner in the late 1970s explains the complex relationship between the individual and cultural norms, socio-economic status and inequality, legal and institutional factors, and the media. We used this model to look at how interpersonal relations and interactions with peers, family members, school teachers and other social networks and support systems influence sexual behaviour. The model provides an opportunity for clarification of one's own values, feelings, beliefs and attitudes, which exist in a social context, and to question assumptions that are prevalent in the cultural environment. | ||||

| • | Rights-based embracing the UN Population Fund's rights-based framework, which argues that the rights of the individual are enforced when institutions assume responsibility for respecting, protecting and promoting them. UNFPA's Framework for Action on Adolescents and Young Adults focuses on how to enable youth to be rights holders by ensuring access to sexual health education to all youth, making health services available to teens, and facilitating opportunities for youth participation in a leadership capacity (www.unfpa.org/webdav/site/global/shared/documents/publications/2007/framework_youth.pdf). | ||||

Field-testing the programme

Before starting the programme in full in LA schools, we decided to do pilot studies to compare the impact of the new classroom curriculum of 12 sessions to a basic curriculum of three sessions. A randomized evaluation has been under way since 2008, conducted by the Center for Adolescent Health and Development at the Public Health Institute in collaboration with the University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine.

PPLA and several public schools signed an agreement allowing for ten high schools to participate in the formal study. Eight schools were independent charter schools (not part of the LA school district) that do not offer health classes but have autonomy to expand on the required curriculum. Two schools were in the LA school district and offered health classes that could include sexuality education. During the formative part of the evaluation, the classroom curriculum was tested in two large public high schools in 2008/09, and a revised curriculum was tested in one public charter high school in 2009/10. In 2010/11, a further field test of all four programme components took place in six schools. The formal randomized evaluation of the full programme started in 2011/12. It employed a two-track randomization design in which four schools received all four programme components, and four schools received only the classroom curriculum, and simultaneously all classrooms in the eight schools were randomized for two types of curriculum, 12 sessions or three sessions. In 2012/13 two more schools were added and randomized in the same fashion. The study will end in 2014 with a final year of follow-up data collection, results analysis and dissemination. To date, 2,608 students and 1,915 parents have participated in the study, and another 1,560 students will be added in the spring of 2013.

As we approach the end of the second year of the evaluation, we have begun to see consistent patterns in the impact of the programme on both students and parents, e.g. preliminary data have shown increases in students carrying condoms with them, and reporting feeling more comfortable talking about sexuality.

Testing the key concepts

The key curriculum concepts were tested in eight focus group discussions with 50 teens and three focus group discussions with 21 parents, which gave invaluable insights into how American teens understand rights in an intimate relationship. When asked about what's important in a relationship, both teen boys and girls cited respect, honesty, privacy and freedom.

Most students strongly agreed that human rights are important and cited the right to self-expression, to vote, to equal education, and to access health care. They also mentioned LGBT and women's rights, and the right to speak Spanish. But when prompted to talk about rights violations, they didn't mention violations of the same rights they had just listed. Instead, they brought up violations of workers' rights and immigration issues like sexual slavery, or the working conditions in sweatshops in which workers – usually immigrants — are subjected to extreme exploitation and forced to work long hours at low wages and under oppressive conditions, including threats and abuse.

When presented with the IPPF Charter of Sexual and Reproductive Rights, students agreed with most of the rights, but identified grey areas, e.g. in differentiating between assertiveness and being abusive. Students seemed clear about social rights, but when applied to relationships, things became blurred for them.

“That's not how it is in real life, like with the right to have friends, and space away from your girlfriend. What really goes on is the cheating, the no trust, the following you around in school.”

“Girls feel that if they say no the guy is going to take it the wrong way… and stuff is going to happen. So it's like their power is taken away, the will to say no is taken from them because they're thinking about the guy.”

“Some girls feel that if a guy buys them a very expensive meal, that is as if he was saying: ‘Look I bought this, what am I going to get in return?’”

Sexuality education in the classroom

When addressing issues like these in the classroom, SEI facilitators validate students' concerns by voicing them to the class, launching a dialogue, and offering suggestions.

“So you are saying that some people don't respect your right to be yourself and have your own space. How might someone feel if their partner is following them around or checking up on them? How could someone talk to a partner about their right to have their own space?”

“You could talk about what trust means to you, because it might mean different things to different people. It is okay if jealousy comes up, if people are willing to talk openly about it. How might someone respectfully express that they are jealous?”

Following the anatomy session halfway through and the last session of the curriculum, facilitators ask students to write down anonymous questions, which are then screened and answered by topic. In a preliminary analysis of 673 questions, 36% were about anatomy, followed by sexual behaviour (27%). Pregnancy and contraception represented 16% of teens' concerns, and 14% referred to doubts about the value of condoms for protection against STIs. In general, boys had more questions about anatomy while girls asked more about behaviour. Overall, teens seemed concerned or curious about what's normal and what's not. “Am I normal” questions and questions about perceived sexual norms from the media or from friends (i.e. penis size, pain at first intercourse, bleeding and virginity) usually surface during these question-and-answer sessions.

Facilitators give direct, science-based answers while protecting student identity. They also use this opportunity to correct common myths about sexuality as well as the prevalence of sexual activity among ninth grade students. Entering high school, students tend to assume that most of their peers are sexually active and are often surprised to learn that nationwide only 33%Citation17 of ninth grade students in 2007 had ever had sexual intercourse.

Peer advocacy training

The peer advocacy programme trains students to be resources for sexual and reproductive health information to the student body. This structured after-school club is sponsored by a teacher and facilitated by skilled PPLA trainers. Each spring students apply to participate in the programme, and approximately ten students are selected at each school. They attend a 30-hour intensive, hands-on training held in the summer, which includes role-playing, sharing of experiences and critical discussions.

Peer advocates are high-achieving students who are involved in extracurricular activities like music, student council and sports. Some have part-time jobs at retail stores or fast food restaurants. Most of them are considering attending in-state colleges, and all are looking forward to graduation and “being out in the real world”. PPLA educators meet weekly with these students throughout the school year for further training and to plan a minimum of four sexual health awareness-raising events against bullying LGBT people for national Coming Out Day, and hosting workshops for World AIDS Day and National Condom Week. For each of these events students develop information sessions, posters, and videos for the student body.

Engaging parents

Surveys with teens in the programme schools have shown that they want to talk to their parents about sexuality, but it's not easy for them and challenging for parents too. Many parents don't feel prepared for those conversations, and to appear ignorant to a child on matters of anatomy can be dreadful. Parent classes offer information that is relevant to adults and facilitate conversations about how to convey to teens their personal or family values about sexuality and sexual behaviour. Additionally, parent coordinators volunteer to advertise parent education classes to the families of students at regular parent gatherings.

The classes and materials used, including the Parent Guide, are intended to remind parents that teens are becoming sexually mature, and that they have rights but still have a lot to learn. Among other tips on how to frame the conversation are the following:

“Even teens who are not having sex still have to make decisions about sex. Saying no takes skills.”

“Loving relationships and intimacy are an important part of adult life.”

“Don't try to scare your teen into not having sex. It doesn't work and may leave them with the wrong information.”

“Remember you don't have to have all the answers, and you don't need to share your own sexual experiences. Listen, be open, and don't focus on bad experiences only.”

“If your teen tells you they are interested in dating people of the same sex, you may not know how to respond to them. But there are resources that can help. Keep talking. The more open you are, the more you can support your teen.”

This is how one mother described the changes in her own household after the programme had been operating for some time:

“With my older daughter I tried to protect her from everything that happens these days, and never talked to her about sexuality, but when my son got involved in SEI, and came home and talked to his sister and us about safe sex and contraception, the whole family started talking. He shares what he's learned with us, at first it was weird, but then I also came to the parent sessions, and now I know what he knows, and we talk, and I trust him to make good decisions!”

Involving teachers

High school students are often sexually active before they have accurate information about sexuality. The curriculum seeks to normalize sexuality education throughout the school. To that end it secures buy-in from the Principal and Assistant Principal at each site, and PPLA staff connect to teachers and faculty who assist in programme scheduling and implementation. Five to seven ninth grade teachers give up their class time for sexuality education. A teacher advisor on each campus sponsors the Peer Advocate Club, opening their classroom after school and assisting students in obtaining proper permission for events. Counsellors and teachers help with peer advocate recruitment each year, in addition to reminding students about the five clinical events on campus described below. Two teachers at each school make their classrooms available for the after-school clinical events so that health services can be provided near a private bathroom. Five to ten self-selecting teachers become trained condom distributors.

Sexual health services on campus

Our experience at Roosevelt High was unique in the sense that it has a full on-site clinic, and the local principal and school nurse understood the benefit of offering sexual health services to students. Unfortunately, most schools do not have a clinic on the premises, and when they do, nurses don't provide sexual health services. Based on the Roosevelt experience, we worked with other schools to bring minimal health services to each campus and assess whether and how that would make a difference to how students acted on the information they received in the classroom.

In all the schools involved in the SEI study, Planned Parenthood brought health care to students. Our premise was that some teenagers may not feel comfortable going to a health center, and having services on campus would make it less foreign and cumbersome for teens to access care.

Each participating school hosts a health care event five times a year after school hours (3–6 pm) offering students confidential and friendly care that includes pregnancy and STI testing, counselling, prescriptions for contraceptives, referrals, individualized follow-up in the case of positive tests, and condoms. The easy access to health services is part of our strategy to integrate learning and practice, as well as to promote a supportive environment where adults care for and can be trusted by teens. In addition to these limited health care events on campus, educators inform students at every classroom session and through peer advocates about the nearest Planned Parenthood clinic in their community, including PPLA's free phoneline and website.

Tools and methodology: films and critical discussions

The Initiative uses films to engage students in critical thinking. Teens are presented with scenarios that are easy to relate to, but complex and nuanced. Facilitators emphasize to students how encompassing sexuality is, and how inter-related feelings and behaviours towards sex and other people are. Building on real life situations, the curriculum uses two films, Bitter Memories and Reflections, which depict the conflicts and difficult decisions teens face in intimate relationships. These were produced by Scenarios USA, an organization that works with teens who write stories from their perspective, in response to the question: “What's the real deal?” The films are then directed by Hollywood film-makers (www.scenariosusa.org/films/film/the-shortest-of-the-shorts/).

The first sexuality education session uses Bitter Memories, a film about masculinity and the cycle of violence. For example, facilitators may start the conversation by saying:

“In the film Bitter Memories, when we saw Rob becoming increasingly irritated and jealous, when he witnessed his partner's behaviour, he tried to communicate with Ashley, but she dismissed his concern by saying it was cute that he was jealous. She confuses jealousy with caring. That can create misunderstandings.”

Reflections, a film about three friends who get tested for HIV and the complex relationships and decisions that lead up to that moment, is used in session nine to highlight HIV prevention, testing and treatment. The film focuses on a young woman who intended to use a condom but then hesitantly decides to have unprotected sex with her older boyfriend. The fact that she abandons her original intention is used as a springboard to a discussion about consent and coercion when one partner has more power than the other, thus allowing students to explore assumptions about consent vs. actual consent, issues of right or wrong in the context of personal values and beliefs, as well as legal implications of rape (which constitutes a crime) and abusive behaviour (as not acceptable).

Training of facilitators

The Initiative relies on skilled facilitators who, in addition to serving as sexuality educators, are trained to guide students through the curriculum, and facilitate the learning process. For the formal evaluation, facilitators were PPLA educators on staff, but they can be volunteers, teachers or community leaders as long as they receive appropriate training in how to make connections between health and social norms, personal behaviour and power dynamics, respect and trust, and so on. Their training includes a structured three-day workshop in a group of 12–15 people, followed by 18 additional hours of shadowing a skilled facilitator at a school, and then individual coaching and practice. The aim is to improve their ability to draw meaningful links that can break gender stereotypes and sharpen teens' critical thinking about social norms.

The training covers social-behavioural norms based on gender, how values are attributed to them, and how gender roles and stereotypes impact sexual behaviours and intimate relationships. Facilitators learn how to question traditional views about men and women, especially with respect to sexual behaviour, sexuality and sexual identity. Facilitators learn to ask question such as:

“How does a couple decide if they are going to have sex? Does it just happen? Or maybe the guy takes the lead? How does that put pressure on guys? How does that put pressure on girls? How do same-sex couples decide to have sex? How could a couple share responsibility when it comes to having sex?”

“If a couple goes out, how do they decide who pays? Are they deciding together who is going to pay? Do you think girls worry more about what their partner is going to think if they say no to sex? What do girls worry about? What about guys? How is this related to being inside or outside the gender boxes? Feeling that you have to conform to the gender boxes can feel really limiting — that you don't have much power to do or say what you want.”

Implementation and challenges

Implementing and evaluating the programme in real time, in public schools where schedules change, principals and teachers leave, schools go on “lock down” mode, or students break into fist fights, has been a huge challenge. Often research studies are implemented in a controlled environment with no unpredictable situations. The Initiative was evaluated under every-day circumstances including last-minute changes to classroom schedules and regular disruption by students with serious behavioural issues or even extreme discomfort with the subject matter. On occasion, entire school campuses have been locked down due to neighbourhood crime. Additionally, students are not used to a learner-centred approach and struggle when asked directly about what they think.

On the positive side, the results will be a real measure of what the programme can do. The four components are working well together. In our experience the new programme is by far the best way to move the needle towards behaviour change. We have worked intently to distil complex concepts and deliver a product that fits into the public school structure and balances information and analytical thinking, including all required evidence-based information, using simple terms and a linear structure. While we are just scratching the surface of these concepts, we are confident that students will come out of the programme better prepared to understand human sexuality as a normal, healthy aspect of human development, that all individuals have human rights, and that teenagers have the right to health care, education, information, protection under the law, dignity and privacy. We aim for them to be able to engage in conversations with parents/guardians or other trusted adults about their personal, family and community beliefs about sexual behaviours, differentiate between an unhealthy and a healthy relationship and be better able to communicate and understand what others communicate in their personal relationships.

Conclusion

By celebrating diversity and promoting understanding of social justice and rights PPLA's Sexuality Education Initiative seeks to enable young people to question harmful assumptions and to stand up against the abuse of power and discrimination. Without critical questioning, girls and young women may remain in a subordinate position to a male partner, and LGBT youth may be either excluded or ridiculed. Our hope is that more and more educational programmes for teens will question assumptions about gender and sexuality that will eventually result in a more respectful and accepting environment for the safe expression of diverse sexual identities.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of the following colleagues: Andrea Irvin, Eva Goldfarb, and Ernestine Heldring in the development of the SEI curriculum; the input from the SEI Project Advisory Group; the expertise of Norm Constantine and Luanne Rohrbach in the design and implementation of the SEI research; and PPLA educators who developed and delivered the full programme. Planned Parenthood thanks its institutional partners in the launching of SEI: Green Dot Public Charter Schools, Los Angeles Unified School District, Partnership for Los Angeles Schools, and Scenarios USA. The authors are grateful to the Ford Foundation and many other donors for their support for this programme.

References

- SIECUS. State Profiles: A History of Federal Funding for Abstinence-Only-Until-Marriage Program. 2010; SIECUS: New York. www.siecus.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=Page.ViewPage&PageID=1340¬eID=1

- Guttmacher Institute. In Brief Fact Sheet: Facts on American teens' sources of information about sex. New York: 2012. www.guttmacher.org/pubs/FB-Teens-Sex-Ed.html#6

- JS Santelli. Explaining recent declines in adolescent pregnancy in the United States: the contribution of abstinence and improved contraceptive use. American Journal of Public Health. 97(1): 2007; 1–7.

- M Vann. Sex ed does delay teen sex. 20 December. 2007; U.S. News & World Report: CDC.

- B King. The need for school-based comprehensive sexuality education: some reflections after 32 years teaching sexuality to college students. American Journal of Sexuality Education. 7(3): 2012; 181.

- G Flores. Toward a more inclusive multicultural education: methods for including LGBT themes in K-12 classrooms. American Journal of Sexuality Education. 7(3): 2012; 187.

- J Herrman, C Moore, B Anthony. Using film clips to teach teen pregnancy prevention: the Gloucester 18 at a teen summit. American Journal of Sexuality Education. 7(3): 2012; 196.

- K Schubert. Analyzing gender and sexuality in magazine advertisements. American Journal of Sexuality Education. 7(3): 2012; 212.

- HD Boonstra. Advancing sexuality education in developing countries: evidence and implications. Guttmacher Policy Review. 14(3): 2011

- Constantine N, et al. No time for complacency: teen births in California. Spring update, 2010. p.4.

- HD Boonstra. Winning campaign: California's concerted effort to reduce its teen pregnancy rate. Guttmacher Policy Review. 13(2): 2010

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases in California: 2009. California Department of Public Health, STI Control Branch, November 2010. www.cdph.ca.gov/data/statistics/Documents/STI-Data-2009-Report.pdf.

- A Davis. Interpersonal and physical dating violence among teens. 2008; The National Council on Crime and Delinquency Focus.www.nccdcrc.org/nccd/pubs/

- UN Population Fund. The human rights-based approach. 13 July 2012. www.unfpa.org/rights/approaches

- SIECUS Answer and Advocates for Youth. Creating a national dialogue about the future of sex education. www.futureofsexed.org/

- U Bronfenbrenner. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. 1979; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behaviour Surveillance. Surveillance Summaries, 2007. Mortality & Morbidity Weekly Report. 57(No. SS-#): 2008