Abstract

The rights of adolescents and young people in international law and agreements have evolved significantly from a focus on protection to a recognition of “evolving capacities” and decision-making ability. Unclear policies and regulations and variations in actual practice may leave providers with little clarity on how to support adolescent decision-making and instead create unintended barriers. This study in Mexico City in 2009 explored whether regulations and clinical attitudes and practice were supporting or hindering the access of adolescent girls aged 12–17 to information regarding abortion and to abortion services. We surveyed abortion clinic directors and staff, and adolescents arranging or just having had an abortion, and sent mystery clients to clinics to ask for information. While providers were generally positive about adolescents' ability to decide on abortion, they had different understandings about the need for adult accompaniment and who that adult should be, and mystery clients seeking information were more likely to receive complete information if accompanied by an adult. Clarification of consent and accompaniment requirements is needed, and providers need to be made aware of them; adolescents should have access to information and counselling without accompaniment; and improvements in privacy and confidentiality in public sector clinics are also needed. These all support complementary concepts of protection and autonomy in adolescent decision-making on abortion.

Résumé

Les droits des adolescents et des jeunes dans le droit et les accords internationaux ont beaucoup évolué, passant d'un accent sur la protection à une reconnaissance du « degré de maturité » et des capacités de décision. Le manque de clarté des politiques et réglementations et les variations dans la pratique réelle peuvent empêcher les prestataires de bien comprendre comment soutenir la prise de décision des adolescents et créer des obstacles imprévus. Cette étude à Mexico en 2009 avait pour but de déterminer si les réglementations et les attitudes et pratiques cliniques favorisaient ou entravaient l'accès des adolescentes âgées de 12 à 17 ans à l'information sur l'avortement et aux services d'avortement. Nous avons enquêté auprès des directeurs et du personnel des centres, et des adolescentes organisant un avortement ou ayant récemment avorté ; nous avons également envoyé des clients mystères demander des informations dans les centres. Alors que les prestataires étaient en général positifs sur la capacité des adolescentes à décider d'avorter, ils concevaient différemment la nécessité d'un accompagnant adulte et qui devait être cet adulte ; les clients mystères avaient plus de chances de recevoir des informations complètes s'ils étaient accompagnés d'un adulte. Il faut préciser les conditions du consentement et de l'accompagnement et y sensibiliser les prestataires ; les adolescents doivent avoir accès aux informations et au conseil sans accompagnement ; et il convient aussi d'améliorer la confidentialité dans les centres du secteur public. Ces mesures soutiennent toutes les concepts complémentaires de protection et d'autonomie dans la prise de décision des adolescents sur l'avortement.

Resumen

En derecho y acuerdos internacionales, los derechos de adolescentes y jóvenes han evolucionado considerablemente desde un enfoque en protección al reconocimiento de las “capacidades evolutivas” y la capacidad para tomar decisiones. Debido a las políticas y normas poco concretas y a las variaciones en las prácticas, a los profesionales de la salud posiblemente no les quede claro cómo apoyar la toma de decisiones de adolescentes y en vez creen barreras no intencionales. En este estudio realizado en la Ciudad de México en 2009, se exploró si las normas, actitudes y prácticas clínicas estaban apoyando u obstaculizando el acceso de las adolescentes de 12 a 17 años a información sobre aborto y servicios de aborto. Encuestamos a la dirección y el personal de una clínica de aborto, así como a adolescentes que habían programado o acababan de tener un aborto, y enviamos usuarias sorpresa a las clínicas para pedir información. Aunque los profesionales de la salud generalmente tenían actitudes positivas respecto a la capacidad de las adolescentes para decidir en cuanto al aborto, tenían diferentes entendimientos de la necesidad de acompañamiento de adultos y de quién debería ser ese adulto; las usuarias sorpresa que buscaban información tenían más probabilidad de recibir información completa si iban acompañadas de un adulto. Se necesita aclaración respecto a los requisitos de consentimiento y acompañamiento y los profesionales de la salud deben estar al tanto de estos; las adolescentes deberían tener acceso a información y consejería sin acompañamiento; y además se necesitan mejoras en privacidad y confidencialidad en las clínicas del sector público. Todos estos aspectos apoyan los conceptos complementarios de protección y autonomía en la toma de decisiones de las adolescentes respecto al aborto.

Over the past century, the rights of young people in international law and agreements have evolved from a focus on “protection from” to a recognition of “evolving capacities” and decision-making ability and a “right to” approach. This is evidenced, for example, in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child 1989, Key Actions for the Implementation of the Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population and Development 1994, and reports from UN treaty monitoring bodies such as CEDAW.

The presumption of decision-making ability until proven otherwise is informed by the concept of “best interests of the child” as described in the Convention on the Rights of the Child: “the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration in all actions affecting children” (Article 3). The concept of “evolving capacity” (Article 5) recognizes that while all young people have the right to protection, participatory and emancipatory rights gradually transfer to young people as they develop the ability to take responsibility for their own actions and decisions.Citation1

With regard to sexual and reproductive health, the recognition of evolving capacity for autonomous decision-making needs to be supported at both a policy and practice level. Regarding policies, according to Rebecca Cook:

“The State must strike a balance between two often seemingly incongruous duties: it must protect adolescents from violence and abuse while simultaneously recognizing the sexual autonomy of individuals who are just beginning to experience their sexuality, and ensure their access to the information and health care they need during this critical developmental stage. The apparently competing nature of these obligations requires States to pay very close attention to the effect of their policies on adolescents, with particular reference to State responsibilities under international human rights law.” Citation2

In April 2007, Mexico City's legislative assembly legalized abortion without restriction up to 12 weeks gestation.Citation17 While this increased access to this critical service for adolescent and adult women alike, it also posed challenges for the implementation of services in relation to adolescents under the age of 18, who in Mexican law, are considered minors.Citation18 In Mexico, the official regulations governing contraceptive services dictates that they be “offered independent of the cause motivating the consultation and demand for these services, to all persons of reproductive age, including adolescents”,Citation19 the General Health Law Regulations for Medical Service Provision and the Mexican Social Security Institute's Medical Services Regulations require that adolescents under 18 years old must be accompanied by an adult or relative to receive a health service. Other official documents, such as the Official Mexican Norm Protocol regarding Health Records,Citation20 specify parental or legal guardian consent for adolescents receiving a surgical intervention. Regarding abortion services specifically, the Mexico City Department of Health's Procedure Manual for Abortion for public provision of services requires parental or guardian consent for adolescents under 18 years of age.Citation21

There seems also to be a lack of agreement about requirements for accompaniment to the NGO/private abortion sector as well, where clinics must be accredited to offer services at all. As regards accompaniment for minors, the website of the Secretaria de Salud (Health Secretariat) says that adolescents should be accompanied by parents or a legal guardian,Footnote* while a website promoting accredited private abortion clinicsFootnote† says that adolescents should come with a person over the age of 18, without specifying who that person should be.

Seeing the potential for conflict between these different policy requirements, we decided to conduct a study in Mexico City two years after the law was changed to explore whether regulations and clinical attitudes and practice were supporting or hindering the access of adolescent girls aged 12–17 (minors) to information regarding termination of pregnancy and to abortion services.

Methodology

We sought the perspectives of two groups for this study: 1) abortion service providers, to understand their knowledge of and attitudes toward institutional policies regarding legal abortion services for adolescents and their beliefs about adolescents' decision-making abilities related to unwanted pregnancy; and 2) adolescents aged 12–17 who had had an unwanted pregnancy, to understand their experiences with unwanted pregnancy and abortion, including who they involved in decision-making, service seeking, perceptions of quality of care and the role that autonomy and confidentiality played in these. Investigación en Salud y Demografía (INSAD), a research organization in Mexico, assisted with study design, fieldwork and data analysis.

The study included five components: focus groups and in-depth interviews with adolescents with unwanted pregnancies, mystery client visits to public and non-governmental organization (NGO) facilities to access information about legal abortion services, quantitative surveys of abortion clinic directors and staff at public and NGO facilities that were providing legal abortion services, and a quantitative survey of adolescents leaving a public hospital who were in the process of seeking or had obtained a legal abortion. The results of the first two componentsFootnote* , published elsewhere,Citation22 focused on decision-making and found that among 23 participants, most autonomously reached a decision to continue or terminate their pregnancies but often needed and sought help to implement their decision. In some cases, this involvement resulted in an outcome which was not their original preference (i.e., they wanted to continue but terminated, or vice versa).

The other three components of the study, which are reported here, focused on experiences within the health system itself. Fieldwork was conducted between January and November 2009. The mystery client component explored how health centre staff in eight public hospitals and three NGO clinics provided legal abortion counsellingFootnote† to minors requesting it. These facilities were included because at the time, all of them were providing legal abortion services to adolescents. In March 2009 (during the study) the Secretary of Health consolidated abortion services for minors into the Centro de Salud Beatriz Velasco, in order to better control the quality of services provided to this vulnerable population.

The mystery client scenarios were designed to identify potential barriers to receiving good quality, comprehensive abortion services. Four individuals, recruited through INSAD personal contacts, were trained for two days to act as an adolescent seeking abortion counselling and information (either accompanied or alone) at the 11 facilities. Since three of the four mystery clients were not pregnant, their contact was limited to what could be obtained prior to having a pregnancy test. The fourth mystery client, who was pregnant, was recruited and trained when it was discovered that a pregnancy test was required by some centres in order to access counselling.

The mystery clients were debriefed immediately following the visit by the research coordinator, using an interview guide developed by the IPPF/WHR and INSAD team to evaluate the information received. The guide included open-ended questions about the visit flow, treatment by staff, staff reactions to the request for abortion services, processes to access information and/or services, and if other staff were made aware of her visit. It also included closed-ended questions about waiting time, visibility of sexual and reproductive rights information, if she and/or her companion were asked their ages; if she was asked for additional documentation; perception of treatment; clarity/completeness of explanations; experiences in the waiting room; confidentiality of consultation rooms; and whether her wish to be accompanied or not into a consultation room was respected.

The quantitative part of the study included interviewer-administered surveys with four clinic directors and a survey with 43 staff (20 from Beatriz Velasco and 23 from NGO clinics) who had contact with women seeking abortion. The staff survey included ten doctors, four psychologists, sixteen nurses, two social workers, ten receptionists, and one sonographer.

The survey aimed to understand any differences between the abortion services in the public clinics and in NGOs specializing in sexual and reproductive health services, including abortion. All of the staff involved in sexual and reproductive health counselling for adolescents in the three NGO clinics and of staff in the abortion clinic at Beatriz Velasco hospital were invited and agreed to participate. The surveys were administered by two investigators, lasting approximately 35 minutes; participants were not remunerated.

The survey of the clinics' staff aimed to understand their knowledge and attitudes regarding legal abortion protocols and requirements, services for adolescents, and adolescent rights and capacity for health decision-making. The directors were asked questions about their clinics' abortion services, including staffing, cost, hours of attention, protocols, requirements for adolescent minors, and perceptions of barriers or particular concerns of adolescents seeking an abortion. In addition to items on protocols, requirements, and perceptions of barriers for adolescents, the staff survey included questions about their training and role in abortion services, perceptions of minors' health decision-making capacity and rights, respect and privacy for adolescents accorded by the institution, and institutional protection for providers in the event of a legal case or complication resulting from an abortion procedure.

The exit interviews were conducted with adolescent patients leaving the Beatriz Velasco hospital who were in the process of arranging or had received a legal abortion. Of the 61 adolescents who completed the survey, 20 were 13–15 years old and 41 were 16–17 years old. The survey lasted approximately 15 minutes; participants were not remunerated. The questions covered the process the participants followed to select the clinic and their perceptions of the quality of care received, including their treatment, privacy, and confidentiality. A convenience sampling strategy was used for recruitment: during a two-week period, all of the female patients leaving the health centre were approached by one of three researchers and asked if they were accessing or had accessed legal abortion services, and if they were interested in participating in a survey about their experiences. A fourth researcher conducted the survey along with the three who recruited the participants. No record was kept of the total number of adolescents approached, but the investigators' perception was that almost 100% of eligible patients had agreed to participate. The survey lasted approximately 15 minutes; participants were not remunerated.Footnote*

We asked how participants selected the hospital, other options they considered, and their perceptions of the quality of care received, including waiting time, information received (requirements and steps in the process of having an abortion), whether services/spaces felt private and comfortable, inclusion of their accompanying person, and whether they had to form a separate line to receive abortion information or services.

All survey data were entered and coded in CSPro by six INSAD researchers between October 2009 and January 2010, and then cleaned and transferred to SPSS for analysis. The mystery client results were entered into an Excel matrixCitation23 for analysis of qualitative and quantitative results.

In Mexico, institutional review board approval is not required for social research; therefore, it was not obtained. However, measures were taken to protect participants. The purpose of the study, the voluntary nature of participation and protections of confidentiality and privacy were explained to all participants. INSAD researchers passed the National Institutes of Health's online course, “Protecting Human Research Participants.” Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants, and they were informed that at any time during the process they could withdraw. Consent was also obtained from the parent or guardian accompanying the exit interview participants, if they were accompanied by an adult. Verbal consent was chosen over written because of the sensitive nature of the subject.

Findings

Mystery clients

A total of 20 mystery client visits were conducted, five to three NGO clinics and 15 to eight public sector facilities. In five of the visits, the mystery client was alone and in 15 she was accompanied by her mother, partner or uncle.

Mystery clients received varying information regarding the accompaniment requirement for minors. In seven of the visits, they were told that an adult family member or any adult or guardian was required, whereas in nine visits, they were told one parent was required, and in four visits that both parents were required. In two centres, different answers were given during two different visits.

Additionally, the basic information provided regarding legal abortion services varied greatly. We defined “basic information” as including requirements for service access, cost, steps included in obtaining an abortion, and types of abortion procedures available. Mystery clients received complete information (all four elements) in nine of the 20 visits, incomplete information (1–3 elements) in ten of the visits and no information in one visit. Mystery clients received slightly more complete information in the NGO clinics, obtaining complete information in three of five visits, as opposed to six of 15 visits in the public sector.

In the six health centres that were visited more than once, there were differences in the completeness of information provided – when the mystery client was accompanied by an adult she received more information than those who went alone. In 11 of the 20 visits, mystery clients received attention that included information or counselling beyond the basic elements, including more detailed information about the abortion procedure and an opportunity to ask questions and address any doubts. In nine of these 11 visits, the mystery client was accompanied by an adult.

For the nine facilities visited for which information was available (three NGO and six public facilities of the 11 total), the need to be accompanied and the first steps in the process of obtaining an abortion differed. In the six public facilities, accompaniment by an adult was required to receive any service, including those that were just informational. In two of the NGO facilities, mystery clients went first for counselling, regardless of whether they were accompanied. In one NGO and two public clinics, an ultrasound was required first, followed by a group informational talk in a public area of the clinic. In the four other public facilities, a physical examination was required first, followed by a group informational talk.

In several of the visits, providers made statements supporting adolescent decision-making about abortion, including one who emphasized that the adolescent (as opposed to her parents) had the right to choose whether to continue the pregnancy. One provider asked about the mystery client's volition in choosing to have sex, and another mystery client was asked whether she was sure of her decision. However, in all but one of the cases in which mystery clients were accompanied, providers did not offer the adolescent an opportunity to talk alone (without the accompanying person). We consider this an important omission in that some adolescents in the other part of our study ended up with a decision about abortion they did not initially prefer.Citation19 This may not have happened if they had been given the opportunity to talk alone.

Additionally, there were cases in which professionals either gave incorrect information (stated that the procedure had to be surgical because the girl was an adolescent or said that the reason an accompanying adult was required was because the procedure was very risky) or made specific judgement statements that appeared related to the adolescent's age (“What we don't want is for adolescents to use this as family planning.”).

Clinic staff perspectives

More than half (55%) of the 32 doctors, nurses, psychologists and social workers surveyed (non-clinical staff and sonographers were excluded) reported receiving training in adolescent care, and 79% reported receiving legal abortion training. A higher proportion of these staff members in the NGO clinics reported receiving training in adolescent care (76%) and legal abortion care (82%) than those in the public sector, 31% and 75%, respectively.

Health centre directors reported different requirements for who accompanied an adolescent minor: the director of Beatriz Velasco and one of the NGO clinics reported requiring any adult whereas those of the other NGO clinics reported requiring an adult relative. None of the four mentioned parents only, let alone both parents.

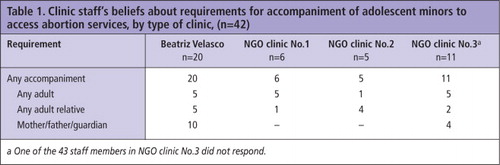

Non-clinical staff and the sonographer's responses regarding accompaniment and other requirements were also variable (Table 1

). In Beatriz Velasco, five responses coincided with the director's, five thought any adult relative was required, and ten thought the girl's parent or guardian was required. In the NGO clinic in which the director mentioned any adult as a requirement, five of the six respondents also mentioned this requirement. In the two NGO clinics where the directors named an adult relative, four of the five staff in one but only two of 11 staff in the other also indicated this requirement.Although 37 of the 42 staff felt the requirements they mentioned shouldn't be changed, 26 felt that the requirement of adult accompaniment was very much or somewhat of a barrier. Three of the five who felt requirements should be changed specifically mentioned removing the need for accompaniment.

Twenty-eight staff felt adolescents should receive abortion counselling tailored to their age and specific needs, on the grounds that adolescents require more information than adult women (29%), have less education (4%), need more examples and less technical language (29%), are less conscientious about contraception and sex (29%), and need to be made more aware of their future (14%), among other responses.

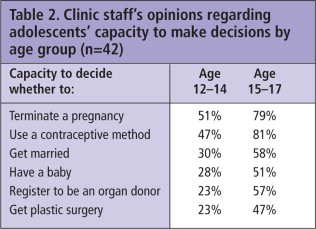

Staff were also asked about their attitudes toward adolescents' abilities to make autonomous decisions about health and life issues. Interestingly, respondents believed adolescents had a greater capacity to make a decision to terminate a pregnancy than decide whether or not they should get married or have a baby. Just over two-thirds also believed adolescents had the right to access abortion services without involving others. Respondents' attitudes varied according to adolescent age, believing overall that older adolescents had a higher capacity for decision-making than younger adolescents (Table 2

).When staff were asked whether adolescents aged 12–19 (to indicate adolescents generally rather than just minors) had the right to make decisions or receive information about different sexual and reproductive health issues, 67% thought they had the right to decide to terminate a pregnancy without involving others in the decision, 77% felt they could decide what type of abortion procedure to receive, and 100% felt they should be able to access sexual and reproductive health information without their parents present. When asked what they would do if an unaccompanied 16- or 17-year-old were to request legal abortion information, 24% said they would provide her only with information about procedure requirements instead of all of the information she might request (76%).

Abortion clinic exit survey

Sixty-one adolescents (aged 13–17) seeking abortion services in Beatriz Velasco hospital were surveyed; 87% said someone helped them to find information regarding abortion services. Overall, almost all of these respondents reported that the treatment they received was “good” or “very good” for each of the three steps of the process (89% to 96%): the first time seeking information, when the process of receiving an abortion was explained, and during the procedure itself. More than 80% of respondents reported that the clinic areas were comfortable and discussion was confidential. The approximately 20% who were not satisfied were concerned about lack of privacy. Thirty-six per cent indicated they had to stand in a separate line to receive abortion information, and 18 of the 39 who received an abortion also had to wait in a separate line the day of the procedure. There was no difference by age.

We also asked whether they were asked if they wanted to have the person accompanying them present when they received information and during the procedure. Staff obtained permission from only 38% of respondents during the steps prior to the procedure and from 26% at the time of the procedure itself.

Discussion

A good proportion of clinic staff in this study acknowledged adolescents' evolving capacities, facilitated autonomous decision-making on abortion, and expressed positive support for counselling that would meet adolescents' specific needs and situations. All of them believed older adolescents had a higher decision-making capacity than younger ones, including the decision to terminate a pregnancy; 79% of providers believed older adolescents had the capacity to decide while 51% felt younger ones possessed the same capacity.

On the other hand, we also found factors that could inhibit access to abortion services for minors in Mexico City, especially those adolescents aged 12–14 and those who arrived alone at a clinic seeking care. It is beyond the scope of this study to conclude either way whether some of the clinic staff's beliefs prevented any adolescent minors from receiving abortion services. Although some differences emerged regarding information and care received, depending on whether adolescents were accompanied or not, the results are not robust enough to draw any firm conclusions. Without receiving complete information, however, the ability of adolescents to make abortion-related decisions could be inhibited. Additionally, although we cannot draw firm conclusions about the effects of adult accompaniment, given that mystery clients tended to receive more complete information and counselling when accompanied, it is important to investigate further whether unaccompanied adolescents are receiving the information and support they need.

The vast majority of adolescents were satisfied with the services and/or information they received, an encouraging indicator of quality of care, and a good sign only two years after the law was changed. However, in 20% of the exit interviews adolescents reported a lack of privacy; more than one-third indicated they had to stand in a separate line to receive abortion information, and nearly half of those had to form a line to receive the procedure. These breeches in privacy should not be difficult to address.

A number of providers had different opinions as to what the health regulations related to minors were, or how to apply them. Knowledge varied greatly among staff as to who was required to accompany minors, and mystery clients experienced similar variation when asking about this requirement. This confusion could cause providers to be more cautious than necessary about providing information and services and could pose unnecessary barriers. For example, most of the mystery clients could not even access counselling without accompaniment even though counselling does not require parental consent.

The ideal approach to assisting adolescents to make their own decisions is one that acknowledges the complementarity of protection and autonomy – that protection is necessary to develop autonomy, and autonomy is necessary to ensure protection.Citation24 Thus, minors should be supported within a protective framework whilst developing new skills, building competence to make decisions and strengthening their autonomy. Based on the findings of this study, the following recommendations could help achieve this goal within Mexico City's legal abortion services:

| • | Convey the message to providers that autonomy and protection are not opposing but, rather, complementary concepts to support adolescents' development and transition to adulthood; | ||||

| • | Clarify consent and accompaniment requirements and ensure all providers are aware of these policies and adolescents receive correct information; | ||||

| • | Re-organize services so adolescents have immediate access to counselling without accompaniment; | ||||

| • | Ensure that all accompanied adolescents are asked if they want their companion to be present or not during counselling and/or the abortion; | ||||

| • | Ensure maximum privacy and confidentiality for adolescents receiving services in public sector clinics, based on successful practice in NGO clinics. | ||||

These recommendations would support the development of young adolescents' capacity to access confidential abortion services while also ensuring they receive necessary support when seeking care.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Investigación en Salud y Demográfica (INSAD), Fundación Mexicana para la Planeación Familiar (MEXFAM) and IPPF/WHR staff member Ilan Cerna-Turoff, Program Coordinator, Adolescents, for their assistance with this article.

Notes

* The participants in these two components were distinct from those included in other components of the study.

† The definition of counselling used in this study is that of Mexico City's Ministry of Health : “Counseling is an obligatory and unalienable health service that provides guidance, advice and objective, accurate, sufficient and timely information about the procedure, risks, consequences and effects, as well as support and alternatives to women who request or require legal abortion.” (Official Gazette of the Federal District. 4 May 2007)

* Patients exiting NGO facilities were not included because the number of abortions for adolescents in those clinics was too low to recruit a sufficient number of participants.

References

- Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Convention on the Rights of the Child. 18 November 2002. http://www2.ohchr.org/english/law/crc.htm#art5

- INPPARES. Acción de inconstitucionalidad: una alternativa para proteger la salud sexual y reproductiva de la adolescencia peruana. [Action of unconstitutionality: an alternative for protecting the sexual and reproductive health of Peruvian adolescents]. 2011; Lima.

- ML Booth, D Bernard, S Quine. Access to health care among Australian adolescents: Young people's perspectives and their sociodemographic distribution. Journal of Adolescent Health. 34(1): 2004; 97–103.

- MT Britto, TL Tivorsak, GB Slap. Adolescents' needs for health care privacy. Pediatrics. 126(6): 2010; e1469–e1476.

- JA Lehrer, R Pantell, K Tebb. Forgone health care among US adolescents: associations between risk characteristics and confidentiality concern. Journal of Adolescent Health. 40(3): 2007; 218–226.

- TL Cheng, JA Savageau, AL Sattler. Confidentiality in health care. A survey of knowledge, perceptions, and attitudes among high school students. JAMA. 269(11): 1993; 1404–1407.

- JS Thrall, L McCloskey, SL Ettner. Confidentiality and adolescents' use of providers for health information and for pelvic examinations. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine. 154(9): 2000; 885–892.

- DM Reddy, R Fleming, C Swain. Effect of mandatory parental notification on adolescent girls' use of sexual health care services. JAMA. 288(6): 2002; 710–714.

- B Ambuel, J Rappaport. Developmental trends in adolescents' psychological and legal competence to consent to abortion. Law and Human Behavior. 16(2): 1992; 129–154.

- MS Griffin-Carlson, KJ Mackin. Parental consent: factors influencing adolescent disclosure regarding abortion. Adolescence. 28(109): 1993; 1–11.

- SK Henshaw, K Kost. Parental involvement in minors' abortion decisions. Family Planning Perspectives. 24(5): 1992; 196–213.

- W Quinton, B Major, C Richards. Adolescents and adjustment to abortion: are minors at greater risk?. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law. 7(3): 2001; 491–514.

- MD Resnick, LH Bearinger, P Stark. Patterns of consultation among adolescent minors obtaining an abortion. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 64(2): 1994; 310–316.

- RH Rosen. Adolescent pregnancy decision-making: are parents important?. Adolescence. 15(57): 1980; 43–54.

- A Torres, JD Forrest, S Eisman. Telling parents: clinic policies and adolescents' use of family planning and abortion services. Family Planning Perspectives. 12(6): 1980; 284–292.

- LS Zabin, MB Hirsch, MR Emerson. To whom do inner-city minors talk about their pregnancies? Adolescents' communication with parents and parent surrogates. Family Planning Perspectives. 24(4): 1992; 148–154, 173.

- Guttmacher Institute. 2008. Legal abortion upheld in Mexico City. www.guttmacher.org/media/inthenews/2008/09/08/index.html

- Mexico. [Political Constitution of the United Mexican States]. www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/pdf/1.pdf

- [Official Mexican Norm of Family Planning], NOM 005-SSA2-1993. www.salud.gob.mx/unidades/cdi/nom/005ssa23.html

- [Official Mexican Norm Regarding Health Records], NOM 004-SSA3-2012. www.idconline.com.mx/media/2012/10/15/nom-004-ssa3-2012-del-expediente-clnico.pdf

- Mexico City Department of Health. [Procedure Manual for the Legal Termination of Pregnancy in Medical Units]. C2008. www.salud.df.gob.mx/ssdf/transparencia_portal/art14frac1/manualile.pdf

- C Tatum, M Rueda, J Bain. Decision-making regarding unwanted pregnancy among adolescents in Mexico City: a qualitative study. Studies in Family Planning. 43(1): 2012; 43–56.

- L Gonzáles Martínez. La sistematización y el análisis de los datos cualitativos, en Mejía R. y Sandoval S. (coord.), Tras las vetas de la investigación cualitativa. Perspectivas y acercamientos desde la práctica. 2007; ITESO: México, 155–174.

- G Lansdown, M Wernham. Are protection and autonomy opposing concepts?. 2012; IPPF: London.