Abstract

Although young people in their everyday lives consume a bewildering array of pharmaceutical, dietary and cosmetic products to self-manage their bodies, moods and sexuality, these practices are generally overlooked by sexual and reproductive health programmes. Nevertheless, this self-management can involve significant (sexual) health risks. This article draws from the initial findings of the University of Amsterdam's ChemicalYouth project. Based on interviews with 142 youths, focus group discussions and participant observation in South Sulawesi, Indonesia, we found that young people – in the domain of sexual health – turn to pharmaceuticals and cosmetics to: (1) feel clean and attractive; (2) increase (sexual) stamina; (3) feel good and sexually confident; (4) counter sexual risks; and (5) for a group of transgender youths, to feminize their male bodies. How youth achieve these desires varies depending on their income and the demands of their working lives. Interestingly, the use of pharmaceuticals and cosmetics was less gendered than expected. Sexual health programmes need to widen their definitions of risk, cooperate with harm reduction programmes to provide youth with accurate information, and tailor themselves to the diverse sexual health concerns of their target groups.

Résumé

Si dans leur vie quotidienne, les jeunes consomment une palette étonnante de produits pharmaceutiques, diététiques et cosmétiques pour autogérer leur corps, leurs humeurs et leur sexualité, ces pratiques sont généralement ignorées par les programmes de santé sexuelle et génésique. Néanmoins, cette autogestion peut comporter d'importants risques de santé (sexuelle). L'article s'inspire des conclusions initiales du projet ChemicalYouth de l'Université d'Amsterdam. Nous fondant sur des entretiens avec 142 jeunes, des discussions de groupe et l'observation des participants à Sulawesi-Sud, Indonésie, nous avons découvert que les jeunes, dans le domaine de la santé sexuelle, ont recours aux produits pharmaceutiques et cosmétiques pour : 1) se sentir propres et attirants ; 2) accroître leur endurance (sexuelle) ; 3) être à l'aise et confiants sexuellement ; 4) contrer les risques sexuels ; et 5) pour un groupe de jeunes transsexuels, féminiser leur corps masculin. La manière dont les jeunes réalisent ces désirs varie selon leur revenu et les exigences de leur vie professionnelle. Il est intéressant de noter que l'utilisation de produits pharmaceutiques et cosmétiques est moins différencié selon les sexes qu'escompté. Les programmes de santé sexuelle doivent élargir leurs définitions du risque, coopérer avec les programmes de réduction des risques pour donner des informations exactes aux jeunes et s'ajuster aux diverses préoccupations de santé sexuelle de leurs groupes cibles.

Resumen

Aunque en su diario vivir las personas jóvenes consumen una desconcertante selección de productos farmacéuticos, dietéticos y cosméticos para automanejar su cuerpo, estado de ánimo y sexualidad, los programas de salud sexual y reproductiva generalmente hacen caso omiso de estas prácticas. No obstante, este automanejo puede implicar riesgos significativos para la salud (sexual). Este artículo se basa en los hallazgos iniciales del proyecto ChemicalYouth de la Universidad de Amsterdam. Mediante entrevistas con 142 jóvenes, discusiones en grupos focales y observación participativa en Sulawesi meridional, Indonesia, encontramos que la juventud –en el ámbito de salud sexual– recurre a farmacéuticos y cosméticos para: (1) sentirse limpia y atractiva; (2) aumentar su resistencia (sexual); (3) sentirse bien y con confianza sexual; (4) contrarrestar los riesgos sexuales; y (5) para un grupo de jóvenes transgénero, feminizar su cuerpo masculino. La manera en que la juventud logra estos deseos varía según su ingreso y las exigencias de su vida laboral. Curiosamente, el uso de farmacéuticos y cosméticos era menos influido por género que lo esperado. Los programas de salud sexual deben ampliar su definición de riesgo, cooperar con programas de reducción de daños para proporcionar a la juventud información exacta y adaptarse conforme a las diversas inquietudes de sus grupos objetivos en cuanto a la salud sexual.

The everyday lives of youth are awash with pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, energy and nutritional products to boost sexual pleasure, performance, appearance and health. While youth routinely use these products to self-manage their bodies and moods, these practices are generally overlooked by sexual and reproductive health programmes that aim to protect and enhance youth sexual health.

Youth consume a bewildering array of chemical products to generate their desired gendered subjectivities – to be sexy, alluring women, or strong, virile men. Recreational drugs, for example, are fuelling a new form of femininity in Granada, Spain, one which emphasizes young women taking the initiative in sexual encounters. While these young women are aware that their sexual disinhibition risks unwanted pregnancy and sexually transmitted disease, they experience this risk as empowering: “Risking it is like an adrenalin boost… by taking risks in my life, I achieved loads of other things….”Citation1 Halfway around the world, young women in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, use limestone and herbal substances (known locally as jamu) intra-vaginally to achieve peret (tightness) to increase friction during intercourse.Citation2 They buy these products discretely in informal stores and market stalls where privacy is guaranteed.

The use of amphetamines and the off-label use of psychoactive prescription drugs are a rising trend among youth in many parts of the world. Studies in the United States have shown that drugs such as methylphenidate (Ritalin) are widely used by university students to aid concentration.Citation3 A study on methamphetamine initiation among students in Chiang Mai, Thailand, found that the drugs were seen as a panacea for tiredness, emotional volatility, and being overweight.Citation4 A young Thai construction worker reports: “I felt I could work more and earn more as well…. when we took yaba [crazy drugs] we became diligent, we didn't feel hungry or tired.”Citation4 Methamphetamines are widely used in Southeast Asia to bolster stamina for physically demanding labour.Citation5

Youth also turn to the off-label use of pharmaceuticals to self-manage their fertility.Citation6 A study among 60 adolescents aged 13–19 in the Philippines found that many had used – or knew of their peers using – tablets (paracetamol, analgesics, etc.) with heated soft drinks as well as Cytotec (misoprostol, on the market for peptic ulcers) as abortifacients.Citation7 Cytotec is a popular pamparegla (menstrual regulation) method for young women in the Philippines, where doctors and health workers often refuse to provide girls with contraception. The use of Cytotec for self-induced abortion has been reported widely in other countries where abortion is illegal.Citation8 Footnote*

Youth themselves are increasingly engaged in sexual rights campaigns and the design and implementation of youth and sexual diversity-friendly services.Citation10,11 Nevertheless, existing programmes generally limit themselves to providing contraceptives and products to prevent and treat sexually transmitted diseases, and tend to ignore how youth use pharmaceuticals and cosmetics to achieve their desired bodily and mental states – practices that can also involve significant (sexual) health risks.

The ChemicalYouth project at the University of Amsterdam aims to understand the pervasive use of chemicals in the everyday lives of young people. Inspired by the anthropology of embodiment,Citation12 the project examines the lived effects of chemicals that youth use to shape their identities and manage their bodies and health – from their own perspective, phenomenologically. Why do youth turn to chemicals? What effects are they seeking? Which chemicals do they use on a daily basis? Which chemicals or combinations of chemicals do they experiment with? How do they obtain and administer the drugs, and in what kinds of social situations? What desired or adverse effects do they experience? How do chemicals affect how youths experience their bodies and selves in relation to each other? This article reports and reflects on the early findings of the ChemicalYouth project in Indonesia as they pertain to sexual health.

Our findings are based on ethnographic fieldwork in two sites in the eastern Indonesian province of South Sulawesi: the provincial capital Makassar and a small coastal town that we call Isidro (we use a pseudonym to protect the identity of our sex worker informants there). Makassar – a regional economic centre, travel hub and home to institutions of higher learning – is a magnet for youths as they seek to work, study and move on in life. Inevitably, young people in this city of 1.4 million encounter a bewildering array of pharmaceuticals, cosmetics and illicit drugs. Isidro is a smaller harbour town several hours by road from Makassar and a popular local tourist destination. It has one of the highest HIV prevalence rates in South Sulawesi.

We recruited youth between 18 and 25 years of age for pragmatic and ethical reasons. We sought to ensure diversity among our informants along the following axes: educational attainment, occupation and income, religious affiliation and lifestyle, living arrangements, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and gender, including transgender individuals. Our fieldwork focused on places where youths gather, including work settings, markets, streets, bars, music scenes associated with specific recreational drugs, shopping malls, schools and private homes.

Methods

While we sought to cast our net wide by recruiting informants from diverse subgroups of youth, we do not claim our findings to be exhaustive or representative of youth in Makassar and Isidro. Our aim here is to provide an overview of common chemical practices and patterns of use specific to selected subgroups of youth, and draw out their implications for youth sexual health policies. Detailed ethnographic insights on subgroup-specific chemical practices, their meanings within youths' social and economic lives, and how specific practices travel will be presented in four other articles emerging from our study.Citation13–16

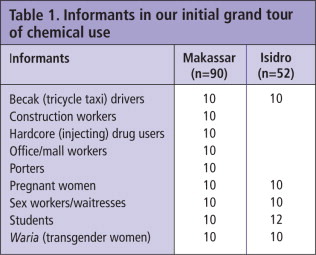

Fieldwork began with a “grand tour” of interviews among different subgroups of youth, (Table 1

) who we found through snowball sampling. For each of the groups in the table, we identified a “seed informant” through our personal and professional networks, who then introduced us to others in their network of friends.In our individual “head-to-toe interviews”, we asked youths which chemicals they applied to their hair, eyes, face, lips, teeth and so on, over their entire bodies, ending with their toenails. This format proved to be an effective means of eliciting information. We began with hair – a key concern for all youth. This usually led to discussions of their preferred brands. The systematic treatment of the human body also seemed to neutralize any squeamishness over discussing its specific parts. “Head-to-toe” also signalled our interest in all chemicals, not only the risky or banned ones. We asked our informants about the products they used, their advantages and disadvantages, whether they had previously used different products and why they had switched. After reading the 142 interview transcripts (each interview lasted for one to two hours), we made a coding scheme for recurring themes and the key terms that youths used to describe the effects of chemicals. For this we employed NVivo10 qualitative analysis software.

We further interviewed about a dozen key informants – pharmacists, store owners, disc jockeys, bar owners and NGO outreach workers – to ask them about the local availability of specific chemicals and the self-management practices that we had observed.

In the subsequent focus group discussions, we delved deeper into our informants' experiences with specific products. In Makassar we held six such focus groups: with construction workers (n=6), mall workers (n=5), students (n=6), sex workers (n=7), hardcore (injecting) drug-users (n=10), and waria (male-to-female transgender individuals) (n=8). In Isidro we held two such focus groups: one with waitresses in the karaoke bars (n=10) and another with waria (n=10). These meetings took place in relatively private spaces: bars, eateries, karaoke bars, and our hotel. The focus groups lasted between two and three hours and were invariably spirited affairs. We bought the products that had been most frequently mentioned in the interviews and placed them on the table to spur discussion. This led to lively debates on how best to use the products and on their relative benefits and drawbacks. Youths spoke not only about their own experiences but about those of their peers, pointing to how their preferences and experiences differed. In these sessions, we also asked youths to fill in recollections of the chemicals they had used over the past four days as well as a form listing the advantages and disadvantages of the products they commonly used.Citation14

Findings

How do youths in Makassar and Isidro use pharmaceuticals and cosmetics to manage their sexual lives? How do their practices differ by gender, working conditions and income? Analysis of the 142 interviews revealed that in the domain of sexual health, youth turn to chemicals to: (1) feel clean and attractive; (2) increase (sexual) stamina; (3) feel good and sexually confident; (4) counter sexual risks; and (5) feminize their male bodies. The latter was only mentioned by the subgroup of waria.

Being “white” and attractive

The most commonly used chemical products in the everyday lives of our informants across the various subgroups were soaps, shampoos, and skin-whitening facial creams. Both young men and young women used them, emphasizing that they needed these products to feel clean and attractive.

Having a white face emerged as a core aspiration among youth (especially before marriage).Footnote* This was seen as essential for finding a pacar (boyfriend or girlfriend) – a future husband or wife. While baby powder was the cheapest (and least invasive) option to achieve whiteness, its use is associated with poverty. Most of our informants used skin-whitening facial creams. The most popular products (such as Diamond and SJ Cream) have long been available. They are relatively cheap and sold in markets but are not advertised through mass media.

Reny, a 21-year-old becak driver, reported using Diamond cream on his face, but only when he goes out to work to prevent his face from burning. In fact it is common to see becak drivers in Makassar wearing long-sleeved shirts and jackets to maintain their light complexions, even when it is very hot. Reny used many other creams as well: Citra body cream to soften his skin and Ponds facial cream to prevent pimples. He learns about the different products from his friends.

Youths with better paying jobs, such as mall workers, often used more expensive products such as Nature-E promoted by popular movie stars. The leaflet below features the movie star Sherina and promotes Nature-E for a “naturally healthy skin”.

Our waitress/sex worker informants in Isidro's karaoke bars told us that having a white face is not only important to feel clean, but to attract clients; competition is strong between the bars, and between the women working in them. They used an aggressive skin-peeling cream called RDL available in the small shops run by the bar owners. It is seen to be highly effective as it peels off the outer layer of darker skin.

RDL Babyface: the most popular skin-peeling product. http://mynailshaven.blogspot.nl/2012/01/rdl-babyface-solution-leaked.html

RDL contains hydroquinone (40 mcg per ml) which decreases the skin's production of melanin. Hydroquinone is banned in most European countries as it increases the skin's sensitivity to harmful UVA and UBA, and is linked to skin cancer. Quinone can also lead to irreversible patches of hyper- or hypo-pigmentation and is dangerous to use when pregnant.Citation20,21 The package leaflet for RDL mentions that it should be used for short periods only. None of our informants, however, had read the insert. RDL is not registered as a cosmetic in Indonesia and is not advertised through the mass media.

Our waitress informants complained that the exfoliating creams feel pedas (hot) on their skin and make it red. We bought a bottle of RDL at the small store run by the karaoke bar owner and were shocked by the strong smell – more like a chemical stain remover than a skin cream. Even so, our informants used it every week. In the focus group we observed a number of women with red faces and dark patches on their skin. When we asked them why they endure such adverse effects, they stressed that in the long run the products do make their skin whiter, and that their customers prefer women with light faces. So they just put up with the side effects. Nina, one of our informants, reported using a fan to cool her face when she uses RDL. She also avoids the sun after her treatments: “In the sun my face turns red, very red.” Other working class informants mentioned using RDL as well, including construction workers who have difficulty maintaining light skins as they work in the sun.

Greater (sexual) stamina

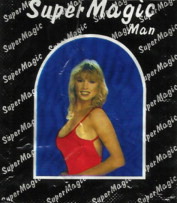

We found youths using a broad range of products to increase stamina and vitality. But only one was explicitly meant to enhance sexual stamina: Super Magic Man, a wet tissue applied to the penis to prolong intercourse, popular among men in South Sulawesi. Its packaging lists no chemical ingredients. We learnt about Super Magic Man when interviewing female sex workers, who complained that men using the tissues want to have sex for longer, meaning they see fewer clients. When we put Super Magic Man on the table during a focus group discussion with mall workers, the young men began giggling. They all knew what it was, and soon admitted to using it.

The male construction workers, becak drivers and porters whom we interviewed all reported using stamina products on a daily basis, prominent among them the energy drinks Extra Joss and KukuBima. Both combine high doses of caffeine with vitamins and ginseng, which is believed to spur sex drive. Their caffeine content is probably what makes them so popular (and addictive). Extra Joss is marketed under the slogan minuman laki (men's drink). But the images of male virility in advertising notwithstanding, we found that most of our informants consumed stamina products for more mundane purposes: to get through their long working days or to unwind after work. Significantly, we saw that women construction workers in Makassar consumed them as well, even though their image in advertising is highly gendered. On one construction site, all the women working there were drinking KukuBima alongside the men.

Advertisement for KukuBima energy drink http://id.wikipedia.org/wiki/Berkas:Kuku-bima.jpg

Feeling good and sexually confident

The “head-to-toe interviews” revealed that young people across the various subgroups used cough suppressants, potent pain killers, benzodiazepines, and locally brewed alcohol (ballo) to feel good. Pills seem to be more popular than alcohol as they can be used without parents noticing (others can smell culturally inappropriate alcohol). The feel-good products are easier to obtain in Makassar where several “naughty” pharmacies sell them without prescription. In Isidro, the health office more closely monitors whether pharmacists are following regulations for selling prescription drugs.

We found the cough suppressant dextromethorphan to be the most popular drug used to feel good (in high doses, dextromethorphan has hallucinogenic effects). Many of our informants reported swallowing 20 to 30 pills of “dextro” at a time, purchased in ready-to-use sachets (containing 50 pills) at the naughty pharmacies. The latter repackage the pills from big generic containers of the medicine, officially on the market for hospital use. Youths with more disposable income favoured other prescription drugs, including the potent painkillers Tramadol and Somadril. Among our hardcore drug user informants, the current drug of choice was the benzodiazepine Calmlet (containing alprazolam), prescribed by psychiatrists and rehab doctors to soften the withdrawal effects of heroin. Knowledge of Calmlet's desirable effects spreads through word of mouth, leading to its use far beyond the small circle of injecting drug users.

Some of our informants were particularly enthusiastic about the painkiller Somadril, which they used to increase their libido and sexual confidence. Somadril contains carisoprodol (mainly a muscle relaxant), paracetamol (an analgesic) and caffeine (a stimulant). Registered as a golongan keras (strong medicine) in Indonesia, it is officially only sold via prescription; the Indonesian pharmaceutical compendiumCitation22 recommends it for aches and pains ranging from lower back pain, tension headache and painful menstruation to chronic arthritis. Carisoprodol, Somadril's major active ingredient, is listed as a Class IV drug in the United States, accepted for short-term use on prescription but flagged for its potential to lead to physical and psychological dependence.Citation23 Carisoprodol has been withdrawn from the European market due to its potential for abuse.Citation14,24

We pursued focused ethnographic study of Somadril use among a group of freelance sex workers operating in Makassar's entertainment district, Losari Beach. The female sex workers reported using Somadril whenever they go out to look for customers; it makes them more pede (confident) and talkative – states of being that facilitate sex work. Our informants consumed Somadril in many different ways. To enhance its effects, some chewed the tablets; others mixed them with the soft drink Sprite (a common solvent for drugs in Indonesia), whisky or vodka. Reflecting local hot-cold notions of chemical efficacy, Somadril was also often consumed together with pedas (hot) food, which our informants reported makes them sweat and enhances the feeling of being high.Citation14

Focused ethnographic enquiry revealed that our informants were addicted to Somadril. They consumed it in large quantities and suffered from headaches, anxiety and trembling when they could not obtain their next hit. While Somadril initially bolstered their confidence and income earning capacity, they admitted that nowadays they worked to buy the drug.Citation14

When they could not score enough Somadril, our informants mixed or substituted it with cheaper psychoactive prescription drugs such as “LL” (also called “DoubleL”, bought from street vendors in sachets of around ten pills, the chemical content of which no one knew) and “Dextro”. Mira was one of the sex workers who kept a diary for us.Citation14 She reported:

May 13 (2012): Last night I took only three pills of Somadril. For me, only taking three pills gives me a bad headache, it feels like my head will break into pieces.

May 14: I took five pills of Somad, and I added DoubleL, and I felt like a fool. DoubleL makes us uncommunicative, and not friendly to people. But I like mixing Somad with DoubleL.

May 15: We didn't have a supply of Somad because we have a debt with the seller. I took 15 pills of Dextro and added three pills of DoubleL, and I felt like I had nothing… no worries, no debt, no sins…. But I am worried that if I take too much, it won't work. It will kill me.

May 16: I took five pills of Somad, and it gave me a headache and I became sleepy…. Dextro makes me sweat like shabu-shabu (methamphetamine), because the heat comes from inside. It makes me feel weak… but it can also make me feel confident if someone asks me for a date.

May 17: I have taken 10 pills of DoubleL, because I am in a bad mood, and I have nothing to do. DoubleL made me feel crazy, we laughed about everything, even things that are not funny.

May 18: I have taken nine pills of Somad and I also drank two bottles of beer, so it feels really good. It's balanced with beer. It makes me sleepy, but I enjoy it because it makes me feel confident.

Mitigating sexual health risks

In our focus groups, we always distributed condoms and inquired about their use. In Makassar, the Regional AIDS Commission (KPAD) and NGOs distribute free condoms as part of national policy. In Isidro, the Department of Health supplies the owners of karaoke bars with free condoms to distribute to their clients and employees. Condoms are readily available in pharmacies and supermarkets for 5,000 rupiah (less than 50 US cents) for a package of three. Even so, our informants told us they do not consistently use them. Often they are too high on Somadril or too drunk to remember; many also said they preferred sex without condoms.

Youth who engage in sex work are particularly vulnerable to HIV infection and sexually transmitted disease. We found the female sex workers in Makassar and the waitresses in Isidro to be well aware of the risks. They tried to reduce them by using Resik-V Bettlenut Liquid Soap, a popular feminine hygiene product that comes in different scents and promises to keep their vaginas healthy, clean, tight and fragrant. Our informants used Resik-V both before and after sex, and to treat vaginal discharge; the product provides them with a means to protect themselves, not only against pathogens but the moral decay associated with sex work. The bottle states in large print that Resik-V contains Piper Betel extract (no concentration given) and in small print lists other ingredients including menthol, lactic acid, ethanol and fragrance.

To further reduce the risk of sexually transmitted infections, female sex workers used ampicillin capsules before and after sex. Ampicillin is freely available without prescription in pharmacies, market stalls and community stores.

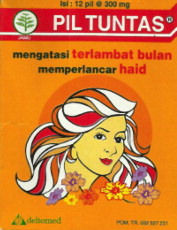

To avoid pregnancy, sexually active young women often resorted to the local herbal drug Pil Tuntas to induce menstruation when it was delayed. The product's packaging promises to “regulate menstruation, cope with menstrual complaints, waist pain, abdominal pain, heartburn, nausea, and acne that arises during menstrual periods”. It further cautions that “Pregnant women should not take this pill”. Their attempts to regulate fertility, however, were not always successful. One young woman in Makassar admitted to having two abortions. Her pregnancies were due to inconsistent condom use when both she and her partner were drunk.

Feminizing male bodies

The use of contraceptive hormones to feminize their bodies was specific to the waria (transgender women) among our informants. They reported that they did not want to become women, but to become like women. They consumed contraceptive hormones – often in large doses – to reduce muscle mass, soften their skins, and grow hips and beautiful breasts.

Most of our waria informants worked in beauty salons during the day; many in Makassar also provided sexual services at night, waiting for clients near a popular shopping mall. Our informants in Makassar bought contraceptives from a local pharmacy. For the sex workers among them, feminizing their bodies was largely about attracting male clients. For our informants in Isidro, being feminine was largely about finding a good husband. A local midwife provided them with contraceptives along with advice on their use.

We pursued a focused ethnographic study of how waria in Makassar consume high doses of contraceptive hormones to transform their bodies. During a focus group, they told us how they experiment with different brands of contraceptive pills as well as injections, all containing a combination of oestrogens and progestins. In determining which products are most cocok (compatible) with their individual bodies, they sought a balance between the hormones' beneficial effects (thicker hair, larger breasts, smoother skin and wasted muscles) and adverse effects (nausea, diarrhoea, weight gain and dizziness, among others). All respondents related intricate stories about their experimentation with different products and means of administering them.Citation13,15

Discussion

The early findings of the ChemicalYouth project in Indonesia have shown that young people use a broad range of pharmaceutical and cosmetic products to enhance and protect their sexual health. We further saw that their concerns are not primarily about unintended pregnancy or sexually transmitted disease. Rather, the chemical practices of youth are shaped by their needs to feel clean, energetic, attractive, happy and sexually confident.

How youths achieve these desires varies depending on their income and the demands of their working lives. The more they earn, the more products they can experiment with to achieve their sexual health aims. But our study revealed that even very poor youths spend much of their income on chemical products, which they feel they need to perform at work. In some cases they become dependent on the chemicals, placing them in a vicious cycle of high expenditures on drugs (such as Somadril or the caffeine-based energy drinks) and the need to earn to feed their addictions.

The popularity of many pharmaceuticals and cosmetics is not, as many social scientists have argued, e.g. Dumit,Citation25 solely the result of aggressive marketing. In South Sulawesi, where internet access remains limited, knowledge of products and practices mainly spreads by word of mouth.

We found chemical practices to be highly situated. The becak drivers in Isidro, for example, use the energy booster KukuBima once a day in the evening; they earn little and prefer to take the energy drink at the end of their working day to feel revitalized when they come home. Their peers in Makassar, who have motorized becaks and earn much more, consume stamina products throughout the day and mix them with soft drinks to make them more palatable. Differences were also evident in the chemical lives of sex workers in our two sites; here the main factor was product availability. All of our sex worker informants in Makassar were heavy users of Somadril, which they bought without prescription from “naughty” pharmacies. In Isidro, Somadril, though desired, was much harder to obtain; its availability was recently regulated by the local health authorities.

Interestingly, the use of pharmaceuticals and cosmetics was less gendered than we expected. Young men used skin-whitening products, especially if they were not yet married; young women used stamina products that are marketed to men. Contraceptive hormones were used by men who feel like women. Rather than dichotomizing bodies as male or female, many of our informants seemed comfortable to view bodies as individually different.

Our preliminary results reveal extreme creativity among youths in experimenting with products to self-manage their sexuality and desired mental and bodily states. The relational notion of cocok (compatibility) was a recurrent theme across the study sites as youths described their experiences with pharmaceuticals and cosmetics. By experimenting with different dosages, forms of administration, and combinations of products, they sought a “fit” between available products and their individual bodies.Citation13

Our informants generally emphasized the desirable effects of cosmetics and pharmaceuticals, knowledge of which seemed to diffuse rapidly within peer networks. They less frequently mentioned adverse side effects. One exception was the skin-whitening lotion RDL, which has immediate and visible effects on the skin. Others pointed to differences between stamina products: KukuBima was safer than Extra Joss, which was said to cause heart palpitations. With the exception of the waria, the long-term risks of chemical use seemed to go unnoticed by most of our youthful informants.

Implications for youth sexual and reproductive health programmes and policies

Sexual and reproductive health programmes need to work together with harm reduction programmes to provide youth with accurate information on illicit drugs (such as amphetamines) as well as on (the off-label use of) prescription medications and stamina products, which though legal can be equally addictive. Many of these drugs not only cause serious side effects and withdrawal symptoms; they also undermine youths' ability to achieve consistent condom use to protect them from sexually transmitted disease.

Sexual health programmes also need to widen their working definitions of sexual risk. Our informants in Makassar and Isidro's public health centres admitted that health workers – while aware of the many practices popular among youths – were unable to address them. While they can distribute (information on) condoms and contraceptives, they are not trained to provide advice on the much wider range of products that young people actually use. Policy-makers and programme managers in Indonesia tend to deny or downplay youth sexual involvement.Citation26 While peer education programmes have been set up with donor support, these are often heavy on the dangers of being sexually active at all. This has left youth popular culture to fill the vacuum.Citation27

Indonesia has a strong public health care system, with local puskesmas (health centres) providing first line health care, including contraception and testing for HIV. But youth generally do not visit these centres, which are perceived to cater to married couples only. Our study reveals that young people do frequent private pharmacies, and that some of the pharmacists in Makassar are deeply concerned about the practices of youth. They would be willing to participate in training programmes and distribute information materials to youth.

Research on condom and contraceptive use among youth often points to unmet needs and gaps between knowledge and practice.Citation6 Our exploratory study in South Sulawesi suggests that the gap between knowledge and practice is filled by all kinds of products that meet youths' need for discretion and which promise sexual pleasure. “Dual-purpose” products such as Resik-V provide a model for reproductive health scientists seeking new preventative methods. If products can, for example, prevent infection while promoting vaginal tightness and fragrance, they stand a much higher chance of becoming popular. There are precedents for this. Sexual pleasure was previously considered in the development of microbicides for women, who valued their lubricating efficacy.Citation28,29 In Indonesia, the Fiesta condom brand, targeting young people with different flavours, colours and shapes, cornered 10% of the market in three years and helped increase overall condom sales by 22%. Marketing research revealed that young people identify Fiesta as “their brand”.Citation30 Conversely, our findings show that sexual health programmes need to provide youth with reliable information on the efficacy of the products they are already using. In doing so, the agency of youth in meeting their own sexual and reproductive health needs should be acknowledged.

Sexual and reproductive health programmes need to tailor themselves to the diverse concerns of specific subgroups of young people. If, for example, transgender women (now targeted by HIV prevention programmes) want to have breasts, why not provide them with information on how to do so safely? Our transgender informants were aware that taking high doses of hormones was risky, but had no idea how they could achieve their goals otherwise. In their outreach to youth, programmes would exclude fewer individuals if they saw gender boundaries as fluid. Existing programmes often assume that young men and women have very different needs. Our study shows that in the domain of sexual health, they also have many common concerns.

We found income levels and working conditions to be important determinants of chemical use. Youth sexual health and harm reduction programmes need to consider the economic role chemical and pharmaceutical products play in the everyday lives of youth and the economic hardship that puts youth at risk. While studies in the affluent world have focused on the recreational use of chemicals, our study in South Sulawesi has shown that chemical use often has an underlying economic logic. Sexual and reproductive health programmes need to acknowledge that chemical practices are highly situated and stratified along socio-economic lines. Sex workers and waitresses fear they will lose clients if they do not use chemicals to lighten their complexions; physical labourers need energy drinks to keep up their hard work. Information on the possible harm caused by these chemical products will have little impact if their economic benefits go unacknowledged. Health and harm reduction programmes need to educate youth to weigh the (sexual) health and economic costs and benefits when deciding which products to consume.

Our “head-to-toe” interview methodology enabled us to capture sexual self-management practices that may otherwise have remained hidden. This simple and effective method can be used elsewhere to examine practices that reflect sexual health needs on the ground as a basis for tailor-made sexual and reproductive health programmes.

Acknowledgements

We thank Amelia Damayanti Ihsan, our research assistant in the project. She was engaged in the fieldwork, including the in-depth interviews and focus group discussions, and helped code the data in NVivo. Her communication skills have contributed much to the quality of the data. We further thank all the young people who were willing to share their chemical lives with us.

Notes

* Misoprostol is used alone or with mifepristone for inducing abortion. See WHO's Safe Abortion: Technical and Policy Guidance for Health Systems, 2012 for details, at: www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/unsafe_abortion/9789241548434/en/. If taken in early pregnancy, in the right dosage and at specified intervals, misoprostol on its own is effective for about 85% of women wanting to terminate their pregnancies.Citation9

* Numerous scholars have addressed skin-lightening practices in different contexts, e.g. for the African diasporaCitation17 and Indonesia.Citation18 Both studies suggest that women of colour use skin-whitening products to have European-like white skin. Bracketing the genealogy of ideas and practices surrounding skin-whitening, youths in our study did not associate “white” with the West but with cleanliness. According to the market research firm Synovate, the use of skin-whitening products is on the rise across East and Southeast Asia.Citation19

References

- N Romo, J Marcos, A Rodriguez. Girl power: risky sexual behaviour and gender identity amongst young Spanish recreational drug users. Sexualities. 12: 2009; 355–377.

- AM Hilber, TH Hull, E Preston-Whyte. A cross cultural study of vaginal practices and sexuality: implications for sexual health. Social Science & Medicine. 70: 2010; 392–400.

- G Quintero, M Nichter, RX Generation. Anthropological research on pharmaceutical enhancement, lifestyle regulation, self-medication and recreational drug use. M Singer, PE Erickson. A Companion to Medical Anthropology. 2011; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, 339–357.

- SG Sherman, D German, B Sirirojn. Initiation of methamphetamine use among young Thai drug users: a qualitative study. Journal of Adolescent Health. 42: 2008; 36–42.

- M Farrell, J Marsden, R Ali. 2002. Methamphetamine: drug use and psychoses becomes a major public health issue in the Asia Pacific region. Addiction. 97(2): 2002; 771–772.

- A Hardon. Women's views and experiences of hormonal contraceptives: what we know and what we need to find out. S Ravindran, M Berer, J Cottingham. Beyond Acceptability: User's Perspectives on Contraceptives. 1997; Reproductive Health Matters: London, 68–75.

- MC Cabaraban, MTSC Linog. Reproductive health and risk behavior of adolescents in northern Mindanao, Philippines. Philippine Population Review. 4: 2005; 1–41.

- RM Barbosa, M Arilha. The Brazilian experience with Cytotec. Studies in Family Planning. 24(4): 1993; 236–240.

- World Health Organization. Safe Abortion: Technical and Policy Guidance for Health Systems. 2012; WHO: Geneva. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/unsafe_abortion/9789241548434/en/

- A Tylee, DM Haller, T Graham. Youth-friendly primary-care services: how are we doing and what more needs to be done?. Lancet. 369(9572): 2007; 1565–1573.

- United Nations. Bali Global Youth Forum Declaration. http://icpdbeyond2014.org/uploads/browser/files/bali_global_youth_forum_declaration.pdf

- TJ Csordas. Introduction: the body as representation and being-in-the-world. TJ Csordas. Embodiment and Experience: The Existential Ground of Culture and Self. 1994; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1–27.

- Hardon A, Idrus NI. On coba and cocok: youth-led drug-experimentation in eastern Indonesia. (Submitted for publication, 2013)

- Hardon A, Ihsan AD. I don't use drugs… Somadril, confidence and sexual pleasure in South Sulawesi. (Submitted for publication, 2013)

- Idrus NI. Chemical waria: the practices of transgender youth in Indonesia to become like women. (Under preparation)

- Idrus NI, Ihsan AD, Hardon A. The chemical lives of sex workers in South Sulawesi. (Under preparation)

- YA Blay. Struck by lightening: the transdiasporan phenomenon of skin-bleaching. Jenda: A Journal of Cultural and African Women Studies. 14: 2009; 1–10.

- S Handajani. Western inscription on Indonesian bodies: representations of adolescents in Indonesian female teen magazines. Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific 2008. http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue18/handajani.htm

- Synovate. Press release: Asian women in pursuit of white skin; 2004. http://stagecurious.mysiteup.com/news/article/2004/06/asian-women-in-pursuit-of-white-skin.html

- B Ladizinski, N Mistry, RV Kundu. Widespread use of toxic skin lightening compounds: medical and psychosocial aspects. Dermatologic Clinics. 29(1): 2011; 111–123.

- Prescrire.org. 2011. www.prescrire.org/Fr/Login.aspx?ReturnUrl=/Fr/C3746FC1DF77BBDCE7CEFD118A13A11D/Download.aspx.

- Informasi Spesialite Obat Indonesia. Penerbit Ikatan Apoteker Indonesia, Volume 46. 2011; Jakarta ISFI Penerbitan: Jakarta.

- Drug Enforcement Administration. Drugs & chemicals of concern: carisoprodol; 2011. www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/drugs_concern/carisoprodol/index.html

- European Medicines Agency. Press release: EMEA recommends suspension of marketing authorisations for carisoprodol-containing medicinal products; 2007. www.emea.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Press_release/2009/11/WC500015582.pdf

- J Dumit. Pharmaceutical witnessing: drugs for life in an era of direct-to-consumer advertising. J Edwards, P Havey, P Wade. Technologized Images, Technologized Bodies. 2010; Berghahn: New York, 37–65.

- BM Holzner, D Oetomo. Youth, sexuality and sex education messages in Indonesia: issues of desire and control. Reproductive Health Matters. 12(23): 2004; 40–49.

- TH Hull, E Hasmi, N Widyantoro. ‘Peer’ educator initiatives for adolescent reproductive health projects in Indonesia. Reproductive Health Matters. 12(23): 2004; 29–39.

- CM Montgomery, M Gafos, S Lees. Re-framing microbicide acceptability: findings from the MDP301 trial. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 12(6): 2010; 649–662.

- C Woodsong, P Alleman. Sexual pleasure, gender power and microbicide acceptability in Zimbabwe and Malawi. AIDS Education and Prevention. 20(2): 2008; 171–187.

- CH Purdy. 2006. Fruity, fun and safe: creating a youth condom brand in Indonesia. Reproductive Health Matters. 14(28): 2006; 127–134.