Abstract

Unsafe abortions remain a major public health problem in countries with very restrictive abortion laws. In Brazil, parliamentarians — who have the power to change the law — are influenced by “public opinion”, often obtained through surveys and opinion polls. This paper presents the findings from two studies. One was carried out in February–December 2010 among 1,660 public servants and the other in February–July 2011 with 874 medical students from three medical schools, both in São Paulo State, Brazil. Both groups of respondents were asked two sets of questions to obtain their opinion about abortion: 1) under which circumstances abortion should be permitted by law, and 2) whether or not women in general and women they knew who had had an abortion should be punished with prison, as Brazilian law mandates. The differences in their answers were enormous: the majority of respondents were against putting women who have had abortions in prison. Almost 60% of civil servants and 25% of medical students knew at least one woman who had had an illegal abortion; 85% of medical students and 83% of civil servants thought this person(s) should not be jailed. Brazilian parliamentarians who are currently reviewing a reform in the Penal Code need to have this information urgently.

Résumé

L’avortement à risque demeure un problème de santé publique majeur dans les pays avec des législations très restrictives. Au Brésil, les parlementaires, qui ont le pouvoir de changer la loi, sont influencés par « l’opinion publique », souvent obtenue avec des enquêtes et des sondages. Cet article présente les conclusions de deux enquêtes réalisées dans l’État de São Paulo, Brésil. L’une a été menée en janvier-juillet 2010 auprès de 1660 fonctionnaires, l’autre en mars-juillet 2011 auprès de 874 étudiants en médecine de trois écoles de médecine. On a posé deux ensembles de questions aux deux groupes de répondants pour obtenir leur avis sur l’avortement : 1) dans quelles circonstances l’avortement devrait-il être autorisé par la loi, et 2) les femmes en général et les femmes dont ils savaient qu’elles avaient avorté devraient-elles ou non être punies d’une peine de prison, comme la loi brésilienne le prévoit. Les différences dans leurs réponses étaient énormes : la majorité des répondants étaient contre l’emprisonnement des femmes ayant avorté. Près de 60% des fonctionnaires et 25% des étudiants en médecine connaissaient au moins une femme qui avait avorté illégalement ; 85% des étudiants en médecine et 83% des fonctionnaires pensaient que ces personnes ne devaient pas être incarcérées. Les parlementaires brésiliens qui examinent actuellement une réforme du code pénal doivent prendre connaissance de ces informations de toute urgence.

Resumen

El aborto inseguro continúa siendo un grave problema de salud pública en países con leyes de aborto muy restrictivas. En Brasil, los parlamentarios – que tienen el poder de cambiar la ley — son influenciados por la “opinión pública”, a menudo obtenida por medio de encuestas y sondeos de opinión. En este artículo se presentan los hallazgos de dos estudios: uno realizado entre enero y julio de 2010 con 1660 funcionarios públicos; el otro, entre marzo y julio de 2011 con 874 estudiantes de tres facultades de medicina, ambos en el estado de São Paulo. A ambos grupos de personas encuestadas se les hicieron dos preguntas para obtener su opinión respecto al aborto: 1) bajo qué circunstancias debería estar permitido por la ley el aborto y 2) si se debe o no castigar a las mujeres en general y a las mujeres que sabían que habían tenido un aborto con pena de prisión, según estipula la ley brasileña. Hubo enormes diferencias en sus repuestas: la mayoría de las personas encuestadas estaban en contra de encarcelar a mujeres que han tenido abortos. Casi el 60% de los funcionarios públicos y el 25% de los estudiantes de medicina conocían por lo menos a una mujer que había tenido un aborto ilegal; el 85% de los estudiantes y el 83% de los funcionarios públicos creían que esa(s) persona(s) no debebería(n) ser encarcelada(s). Esta información debe difundirse con urgencia a los parlamentarios brasileños que están revisando la reforma del Código Penal.

According to the most recent global estimates, while the total number of induced abortions declined between 2003 and 2008, the number of unsafe abortions increased proportionately.Citation1 Unsafe abortions will continue to be a burden for the health and well-being of women in countries where very restrictive abortion laws make it a crime.Citation2 Fortunately, abortion-associated maternal mortality has shown signs of declining, probably as result of the availability of less risky methods being used clandestinely for termination of pregnancy.Citation3

Abortions laws in many parts of the world were inherited from 19th century Europeans laws that existed during colonial times, e.g. in most of Africa. In Latin America they were used as a model when the Penal Codes were written in the first half on the 20th century, e.g. in Brazil.Citation4 The treatment of abortion in these Penal Codes has remained almost unchanged (with a few exceptions), mostly under the pressure of religions that traditionally oppose abortion, particularly the Catholic Church and other Christian faiths in Latin America.

One belief is that if abortion is criminalized, women will have fewer abortions than in an environment of liberal laws and easy access to safe abortions.Citation5 Experience shows this is not realistic, however; in fact, in countries where abortion is legally restricted women have more abortions than those living under more liberal laws.Citation6 Abortion rates appear to be related mostly to women’s access to and use of effective contraceptive methods, not the relative restrictiveness of abortion laws. However, the lack of dissemination of this critical information and the continuous strong opposition of religious leaders play an important role in keeping restrictive abortion laws in place in many developing countries.

In Brazil, the Penal Code dates from 1940 and establishes that abortion is a crime but not punishable in three cases: if the woman’s life is at risk, if pregnancy results from rape, and more recently (since a court judgement in 2012) in cases of fetal anencephaly.Citation7 All other abortions are punishable with 1–10 years in prison both for the woman and for the person who carried out the abortion. The prison term doubles if the abortion leads to the death of the woman.Citation4,8 Many bills have been tabled in the Brazilian Parliament over the years either to increase the restrictions or liberalize the abortion law.Citation9,10 Currently, the Penal Code is under review in the Parliament, causing a heated debate between representatives of the Catholic and Protestant churches and those who defend women’s sexual and reproductive rights.Citation11

Parliamentarians, who have the power to change the law, are heavily influenced by “public opinion”, as could be seen during the 2010 presidential election campaign. The more important national newspapers gave ample coverage to the issue of abortion, with almost four articles published per day.Citation12 The discussion, however, was limited to the moral, religious and political party context. Columns described the care candidates took to avoid being seen to be in favour of a more liberal abortion law, for fear that it could cause them the loss of the election. Even during periods without elections, abortion is mostly presented in the press as a moral/religious issue or in police and crime-related news, particularly the imprisonment of health professionals accused of practising abortions or of women who were reported for having an illegal abortion.Citation12

The fear among politicians of being seen to be in favour of more liberal laws appears to be in contradiction to data obtained in surveys among physicians, judges and prosecutors, the majority of whom have been in favour of broadening the circumstances under which abortion is permitted in Brazil.Citation13,14

On the other hand, the results of “public opinion” polls related to abortion in Brazil, such as those published by different research institutes, are often difficult to compare, because the questions asked can be very different. Most do not make any reference to people’s views on whether women should be put in prison. For example, the Brazilian Senate carried out a survey on the abortion law, where the main question was: “Should the law allow termination of pregnancy when the woman doesn’t want to have a baby?” A large majority of respondents (82%) answered “No”. But when they were asked about concrete circumstances, in which the health of the woman was compromised, the majority were in favour of permitting abortion.Citation11

At the present moment, with the Penal Code under revision, it is crucial to provide Parliamentarians with as much information they can trust as possible. Considering that the answers obtained in surveys depends in great part on how the questions are formulated, the aim of this study was to compare the answers to general questions about the circumstances under which the respondents thought abortion should be allowed, with the answers of the same respondents to the question of whether a woman who has had an illegal abortion should be sent to prison as the law mandates.

Subjects and methods

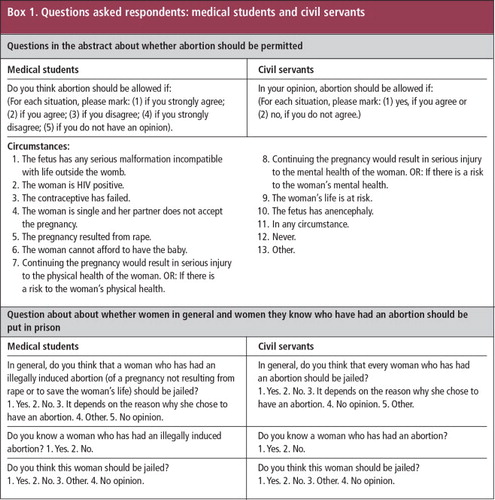

We carried out two cross-sectional, descriptive surveys, one with civil servants from a São Paulo State public institution and the other with medical students from three medical schools, also in São Paulo State. Two different questionnaires were used for the civil servants and the medical students (Box 1), consisting of questions with pre-coded response categories for self-completion. They included information on age, sex, marital status, religion, and the importance of religion in their lives, among other questions.

Regarding Brazilian abortion law, the respondents were asked questions related to their agreeing with abortion being allowed in a list of specific circumstances. Then, they were asked to say whether or not they agreed with punishing women who had had an abortion.

The civil servants study was carried out in February–December 2010. The questionnaire and a covering letter, together with a pre-paid response envelope, were sent out to 15,800 employees along with their January salary statement. The response rate was 11%, 72 of which were sent back blank, and one participant sent back two questionnaires in the same envelope; only one was counted. Therefore, the number of questionnaires included in the study was 1,660.

In February–July 2011, all students from the first to sixth year of the three medical schools were invited to participate in a study by trained research assistants who were responsible for contacting them, explaining the study objectives and collecting the completed questionnaires in a locked ballot box. If none had been absent from any of the three schools, the total number of students invited to participate would have been 1,260. As it happened, 874 completed the questionnaire (response rate 69%).

The answers on both sets of questionnaires were reviewed, numbered and double entered. The dependent variables analyzed for this paper were: opinion on the circumstances in which abortion should be allowed, and opinion about whether to punish a woman who had had an abortion and a known woman who had had an abortion.

Three dependent variables were analyzed: (1) whether abortion should be permitted in any circumstance; (2) whether a woman who had had an abortion should be jailed or not, and (3) whether the known woman should be jailed or not. The predictor variables investigated for all models were the following: age (in years), sex (male/female), marital status (single/living in union) and importance of religion in the participant’s life (very important/Iess important/unimportant/not religious). For the civil servants, schooling was also considered (college education, high school or less). All predictor variables were initially included in all models, and backward elimination criteria were used to retain only the significant ones. When a predictor variable was not significant, it was excluded and a new model was calculated without it.

Poisson multiple regression analysisCitation15 was used to study the relationships between the dependent and predictor variables while controlling for other predictors. Prevalence ratios are presented for the predictors that were statistically significant.

These studies were carried out in compliance with Brazilian norms for research on human beings. The protocols were evaluated and approved by the Ethical Committee on Research, Faculty of Medicine, University of Campinas, SP, Brazil. The research with medical students was also evaluated and approved by the WHO Research Ethics Review Committee.

Results

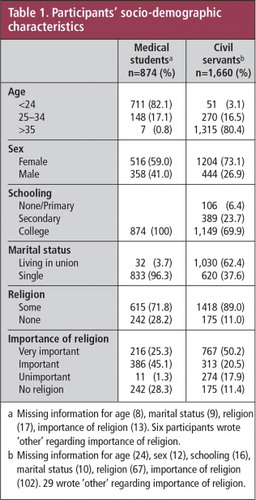

There were several differences between the two groups. The medical students were far younger, with 82.1% below age 24, while 80.4% of civil servants were over age 35. More of the civil servants were female (73.1%) than the medical students (59.9%). Differences in schooling were not as large as expected; all the medical students had some university education, while almost 70% of civil servants did as well. Less than 4% of medical students lived in marital union, as compared with 62% of civil servants. 11% of civil servants said they did not have a religion, compared to close to 30% of medical students. Similarly, just over half the civil servants said that religion was very important in their lives, while 25% of medical students gave that answer (Table 1).

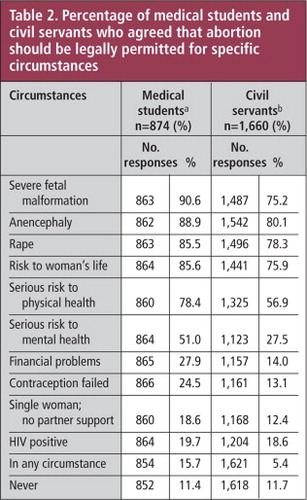

The proportion of medical students who agreed that abortion should be allowed was always larger than the corresponding proportion of civil servants. The difference was of around 10% for the currently legal circumstances: around 85% for medical students and close to 75% for civil servants. The difference was greater than 20% for circumstances currently not included in the law, such as serious risk to the woman’s physical and mental health. Close to 80% of medical students and 57% of civil servants agreed that abortion should be allowed if pregnancy was a serious risk for the woman’s physical health. If the serious risk were for the woman’s mental health, just over half the medical students agreed on allowing abortion compared with just over a quarter of the civil servants. The proportion of respondents who agreed that abortion should be allowed in other social and economic circumstances was well below 50% in both groups. A low percentage of respondents agreed that abortion should be allowed in any circumstances, but it was more than three-fold greater among medical students (16%) than among civil servants (5%). The percentage who thought abortion should never be allowed was 11% in both groups (Table 2).

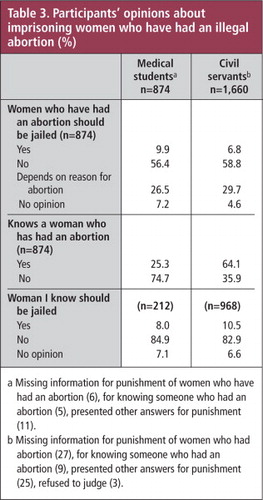

The difference between the two groups was much smaller as regards whether a woman who has had an abortion should go to jail (as the law stipulates). Less than 10% said yes in both groups, while 56% of medical students and 59% of civil servants said no. An additional 26.5% of medical students and 29.7% of civil servants said that it depended on the circumstances, while 7% and less than 5%, respectively, did not have an opinion. Almost 60% of civil servants and 25% of medical students knew at least one woman who had had an abortion. The percentage who judged that this person should be jailed was around 10%, but those who thought she should not be jailed jumped to 85% of medical students and 83% of civil servants (Table 3).

Among students, religion not being important and having no religion were associated with being in favour of permitting abortion in any circumstance and being against putting a woman who had had an abortion in jail (p<0.001). Living in union was also associated with being in favour of permitting abortion in any circumstance (p=0.013), and older age was associated with believing that women who had had an abortion should not be jailed (p=0.011). In the case of personally knowing a woman who had had an illegal abortion, no predictor variables were associated with the opinion that she should be jailed (Tabular data not shown).

The importance of religion and schooling were associated with believing that abortion should be permitted under any circumstance as well as that any woman or a known woman should not be jailed (p<0.001). Civil servants for whom religion was not important or who had no religion and who had some college education were more in favour of abortion being permitted in any circumstance and believed that a woman who had had an abortion should not be jailed (p<0.001) and also that a known woman who aborted should not be jailed (p=0.032). Older age was associated with opposing that any woman (p=0.032) or women they knew who had had an abortion should be jailed (p=0.049) and female sex was also associated with opposition to women who had had an abortion being jailed (p=0.045) (Tabular data not shown).

Discussion

The two groups considered in this analysis were different in many ways. The civil servants were older than the students, and a much larger proportion of them were living in union. Most importantly, a larger percentage of civil servants than medical students had a religion and gave great importance to religion in their life. This explains most of the differences in the percentage of those in favour of permitting abortion in the different circumstances asked about, particularly in the proportion of those in favour of permitting abortion under any circumstances.

Our findings showing that the majority of respondents in both groups at least approved of the grounds allowing abortion currently included in the law, in line with the results of many studies published over the last 20 years.Citation11,13,16–22

Similarly, greater adherence to a religion was the most important factor associated with a more restrictive opinion with reference to abortion law, as was shown in an earlier publication.Citation13 We also found an important association between higher education and a more favourable opinion towards a more liberal abortion law, which is also consistent with the results of other studies.Citation11,16,19

Our study differs from earlier ones, however, by moving from the theoretical question of what the law should permit to asking directly about the practical consequence of the application of the law, that is, whether or not to put a woman who has had an abortion in prison. This approach to public opinion has allowed us to see that the proportion of respondents who disagreed with implementing the punishment mandated in the current law was far greater than the proportion in favour of allowing abortion in any circumstance. While there was still a difference between the two groups when asked about any woman who had had an abortion, the proportion in favour of not punishing (with prison) a woman they knew who had had an abortion was practically identical for both groups in our study.

Which of these questions — one asking what the law should say and the other whether women should be punished with imprisonment — gives a more realistic picture of people’s attitudes toward the abortion law in the country?

Brazil has a cultural environment in which abortion is a bad word, which most people prefer to avoid, and public discussion is mostly limited to the moral and religious point of view, while the situation and the rights of women are rarely considered.Citation12 It is to be expected that in such an environment most people answer the questions related to the law without considering the consequences for women, especially not for women they know. By asking directly about the punishment a woman will suffer if she has an abortion, the respondent cannot ignore the consequences of the current law but is obliged to consider the woman’s situation and her rights. Moreover, when asked to think about a woman they know, the woman’s situation and rights become even more compelling, which is reflected in their answers — that they are overwhelmingly against imprisonment. In a previous study also, we had found that the closer to a person the situation of abortion is, the more that person is willing to see abortion as an acceptable solution.Citation23

The sample we interviewed were not necessarily representative of all Brazilians, but the similarity in the percentage of people in the two groups who were against punishing women with prison in spite of being quite different to each other in many relevant ways, including in their opinion about the abortion law, suggests that the results may not be very different among other samples of the Brazilian population. We hypothesise that our results reflect current opinion in Brazil, which is reinforced by the findings of another study, carried out by the Comissão de Cidadania e Reprodução (Comission on Citizenship and Reproduction),Citation24 with students from six public medical schools in Brazil. When participants were asked to express their opinion on the law, 47% were in favour of the current law, but 79% also said that a woman who has had an abortion should not be jailed, and among the students who said they had no religion, this percentage was 84%. Accordingly, the majority of respondents in that survey as well as in our own two samples were clearly not in favour of maintaining a law that punishes women who have had an illegal abortion with jail. In order to test this hypothesis, it will be necessary to find out, from similar studies among less educated people in São Paulo and other regions of Brazil, how similar or different their views are, a challenge that our own and other research groups should consider taking up very soon.

These views about women who have had an abortion are reflected in the rarity of complaints to the police, prosecutions and actual punishment of women in Brazil, that is, about 100 prosecutions from among the over 1 million estimated abortions per year.Citation25 The well-known case of denunciation of an abortion clinic in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul in 2007Citation26 ended up with not a single woman in jail.

We did not ask the respondents if they would be in favour of another kind of punishment, or what that might be, but only whether they were in favour of the current law and its punishments or not. In fact, people’s opinion on what the law should say with reference to specific women who have had an abortion and on access to safe abortion should be the subject of our research in the near future.

Finally, we consider it our responsibility to disseminate this knowledge — that when people are asked to think about the women who have abortions, most people are against the current punishment of 1–10 years in prison for them. That information has important political implications. The current belief among politicians is that to be in favour of changing the law is politically inconvenient, which means parliamentarians tend to prefer to keep the current situation. To show that when the population thinks about the women, their opinion is radically different, is an important argument in favour of the proposed reform of the Penal Code, which would greatly liberalize the legal situation of abortion in our country. That is our task once this information is published.

Acknowledgments

Financial support for the medical students survey was provided by the Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction and from the São Paulo Research Foundation (Fapesp 11/50203-0). The Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (EDITAL MCT/CNPq/MS-SCTIE-DECIT/CT - Saúde n° 022/2007) supported the survey of civil servants.

References

- World Health Organization. Unsafe abortion: global and regional estimates of the incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2008. 6th ed, 2011; WHO: Geneva.

- United Nations Department for Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World abortion policies. 2011; UN: New York. http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/2011abortion/2011wallchart.pdf.

- E Åhman, IH Shah. New estimates and trends regarding unsafe abortion mortality. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 115(2): 2012; 121–126.

- Brasil. Código Penal: decreto lei n° 2848 de 7/12/1940. 34a ed, 1996; Saraiva: São Paulo.

- A Faúndes, J Barzelatto. The Human Drama of Abortion. 1st ed, 2006; Vanderbilt University Press: Nashville, TN. http://www.reproductive-health-journal.com/content/pdf/1742-4755-2-10.pdf.

- G Sedgh, S Singh, IH Shah. Induced abortion: incidence and trends worldwide from 1995 to 2008. Lancet. 379: 2012; 625–632.

- Conselho Federal de Medicina. Resolução CFM N° 1989/2012. Dispõe sobre o diagnóstico de anencefalia para a antecipação terapêutica do parto e dá outras providências. http://febrasgo.org.br/docs/resolucao.pdf.

- JHR Torres. Aspectos legais do abortamento. Jornal da Rede Saúde. 18: 1999; 7–9.

- MAS de Almeida, FHR Amorim, IAF Barbosa. Legislação Brasileira relativa ao aborto: o conhecimento na formação médica [Brazilian abortion law: knowledge in medical education]. Revista Brasileira de Educação Médica. 36(2): 2012; 243–248.

- MIB Rocha. A questão do aborto no Legislativo brasileiro: uma visão geral dos anos 90 e da década atual. Anais do 16. Encontro Nacional de Estudos Populacionais; 2008 set./out. 29–3; Caxambu. 2008; Caxambu: Abep.

- Brasil. Pesquisa sobre a reforma do código penal [Survey on Brazilian Penal Code reform]. DataSenado: Pesquisas de 2012. http://www.senado.gov.br/noticias/datasenado/default.asp.

- MLA Fontes. O enquadramento do aborto na mídia impressa brasileira nas eleições 2010: a exclusão da saúde pública do debate [The stance on abortion in the Brazilian printed media ahead of the 2010 presidential elections: the exclusion of public health from the debate]. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva. 17(7): 2012; 1805–1812.

- GA Duarte, MJD Osis, A Faúndes. Aborto e legislação: opinião de magistrados e promotores de justiça brasileiros (Brazilian abortion law: the opinion of judges and prosecutors). Revista de Saúde Pública. 44(3): 2010; 406–420.

- LA Goldman, SG García, J Díaz. Brazilian obstetrician-gynecologists and abortion: a survey of knowledge, opinions and practices. Reproductive Health. 2005. http://www.reproductive-health-journal.com/content/pdf/1742-4755-2-10.pdf

- AJD Barros, VN Hirakata. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 3: 2003; 21. http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/pdf/1471-2288-3-21.pdf.

- MJD Osis, E Hardy, A Faúndes. Opinião das mulheres sobre as circunstâncias em que os hospitais deveriam fazer aborto (Women's opinion on circumstances under which hospitals should perform abortions). Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 10: 1994; 320–330.

- GA Duarte, AT Alvarenga, MJD Osis. Perspectiva masculina acerca do aborto provocado (Male perspective on induced abortion). Revista de Saúde Pública. 36(3): 2002; 271–277.

- PE Bailey, ZV Bruno, MF Bezerra. Adolescents' decision-making and attitudes towards abortion in north-east Brazil. Journal of Biosocial Science. 35(1): 2003; 71–82.

- Comissão de Cidadania e Reprodução e Instituto Brasileiro de Opinião e Estatística. Pesquisa de Opinião Pública sobre o Aborto. Junho 2003. http://www.pesquisasedocumentos.com.br/PesquisaIbope2003.pdf.

- A Faúndes, RM Simoneti, GA Duarte. Factors associated with knowledge and opinion of gynaecologists and obstetrician about the Brazilian legislation on abortion. Revista Brasileira de Epidemiologia. 10(1): 2007; 6–18.

- DataFolha. Aumenta a rejeição ao aborto no Brasil após tema ganhar espaço na eleição. Folha de São Paulo, 11/10/2010. http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/poder/812927-aumenta-a-rejeicao-ao-aborto-no-brasil-apos-tema-ganhar-espaco-na-eleicao.shtml.

- RD Medeiros, GD Azevedo, EAA Oliveira. Opinião de estudantes dos cursos de Direito e Medicina da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte sobre o aborto no Brasil (Opinion of medical and law students of Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte about abortion in Brazil). Revista Brasileira de Ginecologia e Obstetricia [online]. 34(1): 2012; 16–21. http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbgo/v34n1/a04v34n1.pdf.

- A Faúndes, GA Duarte, J Andalaft-Neto. The closer you are, the better you understand: the reaction of Brazilian obstetrician-gynaecologists to unwanted pregnancy. Reproductive Health Matters. 12(24 Suppl.): 2004; 47–56.

- Comissão de Cidadania e Reprodução. Percepção dos estudantes de medicina; atenção à saúde reprodutiva, Estado laico e temas relacionados. 2009. http://catolicasonline.org.br/uploads/atividades/Relatorio%20dados%20da%20pesquisa.pdf.

- Gonçalves TA, Lapa TS. Aborto e religião nos tribunais brasileiros. Coordenação de Tamara Amoroso Gonçalves. São Paulo: Instituto para a Promoção da Equidade, 2008. http://www.clam.org.br/publique/media/DocumentoAborto_religiao.pdf.

- Comissão de Cidadania e Reprodução. Aborto: um crime de 10 mil mulheres. http://www.ccr.org.br/uploads/noticias/mt/MSULsintesefinal.pdf Acess 08/30/2013.