Abstract

Progress towards Millennium Development Goal 5a, reducing maternal deaths by 75% between 1990 and 2015, has been substantial; however, it has been too slow to hope for its achievement by 2015, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, including Uganda. This suggests that both the Government of Uganda and the international community are failing to comply with their right-to-health-related obligations towards the people of Uganda. This country case study explores some of the key issues raised when assessing national and international right-to-health-related obligations. We argue that to comply with their shared obligations, national and international actors will have to take steps to move forward together. The Government of Uganda should not expect additional international assistance if it does not live up to its own obligations; at the same time, the international community must provide assistance that is more reliable in the long run to create the ‘fiscal space’ that the Government of Uganda needs to increase recurrent expenditure for health – which is crucial to addressing maternal mortality. We propose that the ‘Roadmap on Shared Responsibility and Global Solidarity for AIDS, TB and Malaria Response in Africa’, adopted by the African Union in July 2012, should be seen as an invitation to the international community to conclude a global social contract for health.

Résumé

Les progrès vers l’OMD 5a, une réduction de 75% des décès maternels entre 1990 et 2015, ont été substantiels, mais néanmoins trop lents pour espérer le réaliser cet objectif d’ici à 2015, en particulier en Afrique subsaharienne, y compris en Ouganda. Cela laisse entendre que ni le Gouvernement ougandais ni la communauté internationale ne respectent leurs obligations liées au droit à la santé envers la population ougandaise. Cette étude de cas de pays explore certaines questions clés soulevées lors de l’évaluation des obligations nationales et internationales relatives au droit à la santé. Nous avançons que pour s’acquitter de leurs obligations partagées, les acteurs nationaux et internationaux devront prendre des mesures pour avancer ensemble. Le Gouvernement ougandais ne doit pas attendre d’aide internationale supplémentaire s’il n’honore pas ses propres obligations ; en même temps, la communauté internationale doit prodiguer une assistance plus fiable à long terme dans le but de créer « l’espace fiscal » dont le Gouvernement ougandais a besoin pour relever les dépenses de santé récurrentes, ce qui est essentiel pour lutter contre la mortalité maternelle. Nous proposons que la « Feuille de route sur la responsabilité partagée et la solidarité mondiale dans la riposte au SIDA, à la tuberculose et au paludisme en Afrique », adoptée par l’Union africaine en juillet 2012, soit considérée comme une invitation lancée à la communauté internationale en vue de conclure un contrat social mondial pour la santé.

Resumen

Se han logrado considerables avances hacia la consecución del Objetivo 5a de Desarrollo del Milenio, reducir la mortalidad materna en un 75% entre 1990 y 2015; sin embargo, estos han sido demasiado lentos para cumplir el objetivo para 2015, particularmente en Ãfrica subsahariana, incluida Uganda. Esto indica que tanto el Gobierno de Uganda como la comunidad internacional no están cumpliendo sus obligaciones para con el pueblo de Uganda respecto al derecho a la salud. Este estudio de caso de país explora algunos de los asuntos clave planteados al evaluar las obligaciones nacionales e internacionales relacionadas con el derecho a la salud. Argumentamos que para cumplir sus obligaciones compartidas, los actores nacionales e internacionales deberán tomar medidas para seguir adelante de manera conjunta. El Gobierno de Uganda no debería esperar recibir más ayuda internacional si no cumple sus obligaciones; asimismo, la comunidad internacional debe brindar asistencia que sea más fiable a la larga para crear el ‘espacio fiscal’ que el Gobierno de Uganda necesita para aumentar los gastos recurrentes en salud, que es crucial para tratar el problema de mortalidad materna. Proponemos que el ‘Mapa de responsabilidad compartida y solidaridad mundial en respuesta al SIDA, la TB y la malaria en Ãfrica’, adoptado por la Unión Africana en julio de 2012, debe considerarse como una invitación a la comunidad internacional para concluir un contrato social mundial para la salud.

Reducing maternal deaths by 75% between 1990 and 2015 is one of the main goals of Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 5 (goal 5a). While progress towards this goal has been substantial, it has been too slow to hope for its achievement by 2015, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa.Citation1 For example, according to the WHO World Health Statistics 2013 report, in 2010 the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) in Uganda was 310 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births, whereas a decade earlier it had been 530.Citation2 This is progress, but there is no room for complacency.

In a ground-breaking resolution adopted in 2009, the United Nation Human Rights Council recognized that preventable maternal mortality is a human rights violation, proclaiming that “most instances of maternal mortality and morbidity are preventable, and that preventable maternal mortality and morbidity is a health, development and human rights challenge that also requires the effective promotion and protection of the human rights of women and girls” (Article 2).Citation3

While there is no human right to be healthy, the human right to “the highest attainable standard of health” (the right to health) means both that every human being has entitlements to public efforts to improve or preserve her or his health, and to enjoy freedom from interference that would be detrimental to their health.Citation4 For the people of each State, the duty-bearer is, first and foremost, their Government, followed by the international community as the second line duty-bearer, and specifically “States in a position to assist”.Citation4

In this paper, we argue that both the Government of Uganda and the international community are failing to comply with their right-to-health-related obligations towards the people of Uganda, and that in order to comply, they will have to take steps forward together. The Government of Uganda should not expect additional international assistance if it does not live up to its own obligations, but at the same time, the international community must provide assistance that is more reliable in the long run to create the ‘fiscal space’ that the Government of Uganda needs to increase recurrent expenditure for health – which is crucial to addressing maternal mortality.

To clarify the multiple issues raised when assessing national and international right-to-health-related obligations, we adopted a county case study approach, as it allows for a more in-depth detailed analysis. We chose to focus on maternal mortality in Uganda because the scope of the Government of Uganda’s right-to-health-related obligations is the subject of a petition filed in the Constitutional Court, which testifies to the growing realisation of the importance of clarifying this issue.Citation5

Our analysis will focus on four points:

that mobilising resources matters; while it is not the only factor in reducing maternal mortality, it is an important one; | |||||

that many states are failing to comply with their obligation to mobilise maximum available resources, both domestically and in terms of international assistance; | |||||

that health aid has to become more reliable to enable the effective use of additional domestic resources; and | |||||

that the ‘Roadmap on Shared Responsibility and Global Solidarity for AIDS, TB and Malaria Response in Africa’, adopted by the African Union in July 2012, should be seen as an invitation to the international community to conclude a global social contract for health.Citation6 | |||||

Mobilising resources matters

Several reasons have been put forward to explain the failure to achieve MDG 5a in sub-Saharan Africa, including a shortage of financial resources, lack of political will, vague legislation and policy that do not pinpoint responsibility, cultural beliefs, gender-based discrimination, education and literacy challenges, health system weaknesses (including lack of health professionals with adequate skills and training) and a range of infrastructural deficiencies.Citation7

The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights indicates that the rights it describes impose corresponding obligations: “to take steps, individually and through international assistance and co-operation, especially economic and technical, to the maximum of its available resources, with a view to achieving progressively the full realization of the rights recognized in the present Covenant” (emphasis added).Citation8 Is the Covenant’s focus on maximum available resources warranted and what does it mean?

It is difficult to track government health expenditure for maternal health in particular. Furthermore, in line with Freedman and colleagues, we argue that instead of focusing on “the fine points of precisely which effective [maternal health] interventions theoretically fit best into generic packages, we now need to address the health system that must deliver them.”Citation9 Therefore, we examined the recent evolution of government health expenditure (GHE) – that is, for the entire health system.

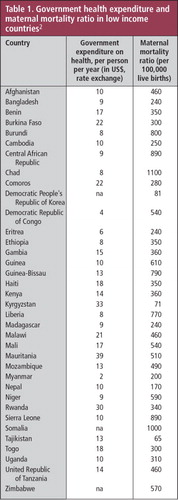

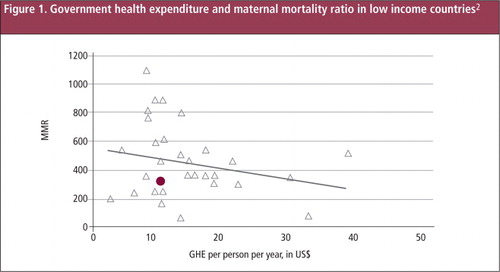

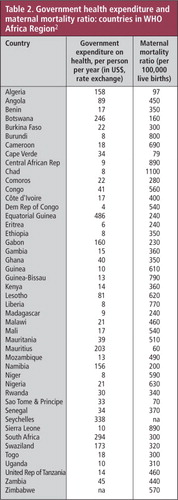

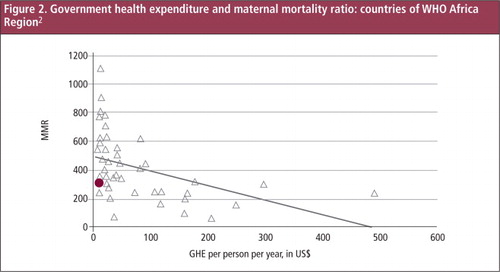

Table 1 and below illustrate the relationship between GHE (in US$ per person per year) and the MMR in low-income countries. Table 2 and illustrate the relationship between GHE and MMR in all countries of the WHO Africa region. The distances between the dots and the trend lines illustrate that how financial resources are spent is as important as how much resources are allocated. In Chad, for example, where GHE stands at $8 (per person per year), the MMR is 1,100 per 100,000 live births, while in Madagascar the MMR is only 240, with GHE at $9. Scholars have examined several hypotheses to explain this irregular correlation. Unger and colleagues argue that disease control programmes have negatively affected health systems and consequently maternal health care.Citation10 Penn-Kekana and colleagues note that “there are also frequent examples of failure to render strategies effective or to deliver them to intended groups despite the availability of inputs and appropriately trained staff in the right place at the right time.”Citation11

The purpose of our analysis, however, is not to examine why additional financial resources may not always produce the desired effect of stronger health systems and decreasing maternal mortality, but to analyse why it is difficult to increase the financial resources. The question at this point is not whether government health expenditure is the only factor; the question is whether it is an important factor. Or to put it another way, can countries like Uganda lower their maternal mortality ratios without increasing their financial resources for health?

In Uganda (the round dot in the figures), GHE stands at $10, and the MMR at 310. Among 23 low-income countries with comparable levels of GHE ($15 or less), only seven have a lower MMR (and are arguably allocating GHE more efficiently when it comes to reducing the MMR): Bangladesh, Cambodia, Eritrea, Madagascar, Myanmar, Nepal and Tajikistan. The other 15 countries have a higher MMR. Among 14 countries in the WHO Africa region where the MMR is lower than in Uganda, only two have similar or lower GHE: Eritrea and Madagascar. So there probably is some room to further reduce the MMR in Uganda without increasing GHE, but not much.

We therefore argue that the conclusion of Borghi and colleagues of 2006 is still valid today:

“Current investment in maternal health is insufficient to meet MDG 5, and substantial additional resources will need to be mobilised to strengthen the health system to scale up coverage of maternal health services and to create demand for these services through appropriate financing initiatives.”Citation12

Both the Government of Uganda and the international community are failing to comply with their obligations towards the people of Uganda

To comply with its right-to-health-related obligations under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the Government of Uganda is obliged to take steps to progressively realise the right to health, to the maximum of available resources.Citation8 The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, and General Comment 14, clarify that when a government is unable to respect, protect and fulfil its right-to-health-related obligations, the international community – notably other countries in a position to assist – are obliged to provide assistance.Citation4

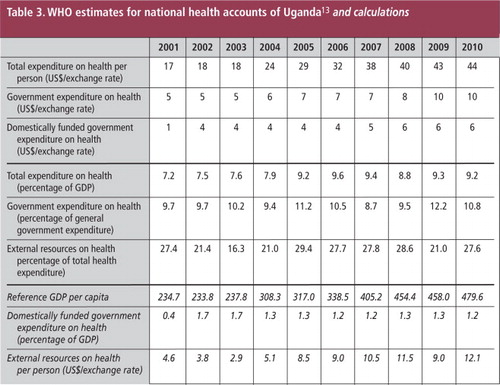

To assess whether the Government of Uganda is spending the maximum of available resources, we looked at the WHO estimates for Uganda’s national health accounts, from 2001 until 2010.Citation13 Total health expenditure increased substantially, from US$17 per person per year in 2001 to $44 per person per year in 2010. However, most of the increase seems to be due to private expenditure (private insurance and out-of-pocket payments) and external resources, as Table 3 illustrates.Citation13

Domestically funded GHE made one big jump in 2002, the year after the Abuja Declaration on HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and other diseases, where Heads of State and Government of the Organization of African Unity (now the African Union) committed to allocating 15% of their budgets to the improvement of the entire health sector.Citation14 Accordingly, in 2002 Ugandan domestically funded GHE increased to $4 per person per year, from $1 in 2001. But from 2002 onwards domestically GHE increased very slowly, in absolute amounts: from $4 per person per year in 2002 to $6 in 2010. Furthermore, considering the gross domestic product (GDP) of a country as the source of potential government revenue, we calculated domestically funded GHE as a percentage of the GDP, and found that domestically funded GHE fell from 1.7% of GDP in 2002 to 1.2% of GDP in 2010.

Yet the obligation imposed by the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights is not simply for governments to act individually, but also for the international community to progressively realise rights by providing international assistance and co-operation.Citation4 While the extent of the obligation to provide international assistance remains a subject of controversy, the existence of the obligation is not. In 2011, a group of international lawyers and human rights experts, drawn from universities and organisations throughout the world, drafted and adopted the ‘Maastricht Principles on Extraterritorial Obligations of States in the area of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights’.Citation15 This document, which covers the right to health, although not legally binding, is an authoritative statement that is the product of over ten years of research and activity in the field. It argues that:

“[i]n fulfilling economic, social and cultural rights extraterritorially, States must: a) prioritize the realization of the rights of disadvantaged, marginalized and vulnerable groups; b) prioritize core obligations to realize minimum essential levels of economic, social and cultural rights, and move as expeditiously and effectively as possible towards the full realization of economic, social and cultural rights …” Citation16

In Uganda, according to the WHO data on which Table 3 is based, the GDP per person was US $479 in 2010.Citation13 Even if the Government of Uganda could increase government revenue to 20% of GDP, which would be quite high when compared with countries in comparable situations, that would allow the Ugandan Government to contribute only $96 per person per year in domestic funding to its entire budget.Citation17 If the Government of Uganda would then spend 15% of that budget on health, as promised in the Abuja Declaration, the domestically funded GHE would increase to $14 per person per year – as compared to the 2010 level of $6 per person.Citation13

The High-Level Taskforce on Innovative International Financing for Health Systems found that, in low-income countries, the annual costs of achieving the current health sector MDGs would be about $50-55 per person per year.Citation18 Even if we take private expenditure out of the equation – according to the World Health Report of 2010, it is “only when direct payments fall to 15–20% of total health expenditures that the incidence of financial catastrophe and impoverishment falls to negligible levels”– GHE should still be at least $45 per person per year.Citation19 The gap between $45 per person per year and $14 (what domestically funded GHE could be) is $31, and that is what the international community must provide, at the least, to enable the Government of Uganda to comply with the health sector part of its core right-to-health-related obligations: “basic arithmetic”, according to Sachs.Citation20 At present, however, aid to Uganda is about $10 per person per year, or a third of the $31 gap. Furthermore, it should be noted that the $10 per person per year in aid covers all external resources, including the resources that are spent outside of the government budget. If total GHE is $10 per person per year in 2010, and domestically funded GHE is $6, then ‘on budget aid’ is merely $4 per person per year – while it should be $31.

The Government of Uganda and the international community have to take steps forward together

Table 3 suggests that Uganda is a textbook example of ‘displacement’: when international assistance for a given programme increases, domestically funded public expenditure for the same programme tends to decrease.Citation21,22 In Uganda, between 2002 and 2010, there was no decrease of domestically funded GHE in absolute amounts, but there was a serious decrease when measured as a percentage of GDP, as Table 3 illustrates.

But what were the Government of Uganda’s options? While domestically funded GHE increased from $4 per person per year in 2002 to $6 in 2010, total GHE increased from $5 per person per year 2002 to $10 in 2010. This indicates how ‘on budget’ aid increased from $1 per person per year in 2002 to $4 per person per year in 2010: not enough, but nonetheless about $140 million out of total GHE of about $350 million. The Government of Uganda could have – and we argue: should have – increased GHE to at least $18 per person per year: $14 from its own resources, in addition to the $4 in aid it receives.

If one of the goals of health aid is to encourage governments to increase GHE, that aid needs to be sustained and reliable in the long run. However, as Lane and Glassman argue, aid is unreliable and “therefore poorly suited to fund recurrent costs associated with achieving the Health Millennium Development Goals, particularly funding of Primary Health Care”.Citation23 At the same time, Foster observes that “donor disbursement performance remains volatile and unreliable”, and that “[g]overnments are therefore understandably reluctant to take the risk of relying on increased aid to finance the necessary scaling up of public expenditure”.Citation24 Heller summarises the conundrum governments face as follows:

“External grants can clearly provide fiscal space, in contrast to borrowing (which implies the obligation for future debt-service payments). But a sustained and predictable flow of grants is essential, since it reduces the uncertainty as to whether a grant is simply of a one-time character and creates the potential for a scaling-up of expenditure to be maintained in the future. Regrettably, few donors now are willing to make external assistance commitments for more than one or two years.” Citation25

The Government of Uganda had several options: refusing part of the aid offered, because it is unsuited for recurrent expenditure, or accepting as much health aid as it could obtain, while allocating its own resources to reserves for other sectors. While neither of these options can be justified from a right-to-health perspective, the latter is obviously the most attractive option from the point of view of the Government of Uganda.

Furthermore, the Government of Uganda may not have been alone in deciding this. In 2005, Ooms and Schrecker denounced the existence of expenditure ceilings in Uganda, imposed by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF).Citation26 Stuckler, Basu and McKee found evidence in support of their hypothesis that World Bank and IMF policies “advise governments to divert aid to reserves to cope with aid volatility and keep government spending low”.Citation27

These arguments provide an alternative explanation for ‘displacement’ in Uganda: perhaps the Government of Uganda did not want to go over GHE at $10 per person per year, because it was concerned that aid was unreliable in the long run.

In this light, the Government of Uganda and the international community appear to be holding each other hostage. The international community would be reluctant to increase health aid to Uganda further: it financed most of the increase in GHE between 2002 and 2010, and although the GDP of Uganda doubled in size, the Government allocated the additional revenue elsewhere. But if the international community does not make long-term aid commitments, then the Government of Uganda in turn could be reluctant to increase GHE, because it does not want to create expectations that it may not be able to meet in the longer term.Citation28

The ‘African Union Roadmap on Shared Responsibility and Global Solidarity for AIDS, TB and Malaria Response in Africa’ provides a way forward

How can this deadlock be broken? Governments like the Government of Uganda should be encouraged to increase domestically funded GHE without running the risk of seeing wealthier states reduce their health aid; and the international community should be encouraged to increase health aid to Uganda without running the risk of seeing the Government of Uganda decrease domestic funding for health. States needing assistance and states providing assistance should aim for a global social contract for health, based on the right to health, under which they make reciprocal commitments and under which they can hold each other accountable for agreed increases in both domestically funded GHE and health aid.

A first major step towards such a global social contract has been taken already. In July 2012, the African Union adopted a ‘Roadmap on Shared Responsibility and Global Solidarity for AIDS, TB and Malaria Response in Africa’ (Roadmap), which calls on African governments and on the international community to fill the funding gaps together.Citation6 Although the title of the Roadmap refers to AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria only, it contains proposals about financial responsibility for health in general, and about reciprocal responsibility. Section 39 of the Roadmap states:

“Protecting development assistance, however, will require more visible southern leadership and commitment to increased domestic and diversified funding and effective and efficient use of resources.” Citation6

The Roadmap suggests that African Union members are willing to be held accountable for their efforts in relation to the commitments they have made, but expect in return longer-term predictable health aid. Now it is time for the international community to acknowledge the offer, and to prepare an answer, in line with its own existing commitments.

Although the suggestions in the Roadmap are not precise enough to serve as the basis for a binding treaty, they can be considered as an opening bid: increased domestic funding in return for increased and more reliable aid, and vice versa. A Framework Convention on Global Health could formalise the principles of such a global social contract for health, while a protocol on financing could set targets, to be revised regularly, until all preventable maternal mortality is indeed effectively prevented.Citation29

Within the context of the post-2015 agenda, we consider the Roadmap as a bid worth considering. While we think it remains important that the post-2015 health agenda keeps a focus on priority health issues, including maternal mortality and sexual and reproductive health and rights, specific needs have to be addressed within the context of health systems as a whole. In order to ensure that increased domestic funding for health does not displace health aid, or vice versa, and that GHE from all sources combined increases, we believe a global social contract for health is required.

Acknowledgments

This study is part of the Go4Health research project, funded by the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme, grant HEALTH-F1-2012-305240, by the Australian Government’s NH&MRC-European Union Collaborative Research Grants, grant 1055138, and by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Operating Grant, Ethics grant 131587.

References

- United Nations. Millennium Development Goals Report 2011. 2012. http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/11_MDG%20Report_EN.pdf

- World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2013. 2013. http://www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/2013/en/

- United Nations Human Rights Council. Preventable maternal mortality and morbidity and human rights. Resolution 11/8 U.N. Doc. A/HRC/RES/11/8. 2009. http://ap.ohchr.org/documents/E/HRC/resolutions/A_HRC_RES_11_8.pdf

- Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. General Comment 14, The right to the highest attainable standard of health. U.N. Doc. E/C.12/2000/4. 2000. http://www1.umn.edu/humanrts/gencomm/escgencom14.htm

- Centre for Health, Human Rights and Development. Advocating for the Right to Reproductive Health Care in Uganda, The Import of Constitutional Petition No. 16 of 2011. 2012. http://www.cehurd.org/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2012/01/Petition-16-Study.pdf

- African Union. Roadmap on Shared Responsibility and Global Solidarity for AIDS, TB and Malaria Response in Africa. 2012. http://www.au.int/en/sites/default/files/Shared_Res_Roadmap_Rev_F%5b1%5d.pdf

- S Karlsen, L Say, J Souza. The relationship between maternal education and mortality among women giving birth in health care institutions: analysis of the cross-sectional WHO Global Survey on Maternal and Perinatal Health. BMC Public Health. 11: 2011; 606. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/11/606.

- International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, G.A. res. 2200A (XXI), 21 U.N.GAOR Supp. (No. 16) at 49, U.N. Doc. A/6316 (1966), 993 U.N.T.S. 3, entered into force Jan. 3, 1976. http://www1.umn.edu/humanrts/instree/b2esc.htm.

- LP Freedman, WJ Graham, E Brazier. Practical lessons from global safe motherhood initiatives: time for a new focus on implementation. Lancet. 370(9595): 2007; 1383–1391.

- J-P Unger, P Van Dessel, K Sen, P De Paepe. International health policy and stagnating maternal mortality: is there a causal link?. Reproductive Health Matters. 17(33): 2009; 91–104.

- L Penn-Kekana, B McPake, J Parkhurst. Improving maternal health; getting what works to happen. Reproductive Health Matters. 15(30): 2007; 28–37.

- J Borghi, T Ensor, A Somanathan, on behalf of Lancet Maternal Survival Series steering group. Mobilising financial resources for maternal health. Lancet. 368(9545): 2006; 1457–1465.

- World Health Organization. National Health Accounts; Uganda; WHO estimates for country NHA data. http://www.who.int/nha/country/uga/en/

- Organisation of African Unity. Abuja Declaration on HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Other Related Infectious Diseases. 2001. http://www.un.org/ga/aids/pdf/abuja_declaration.pdf

- O De Schutter, A Eide, A Khalfan. Commentary to the Maastricht Principles on Extraterritorial Obligations of States in the area of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 28 September 2011. Human Rights Quarterly. 34: 2012; 1084–1169. http://www.lse.ac.uk/humanRights/articlesAndTranscripts/2012/HRQMaastricht.pdf.

- The Maastricht Principles on Extraterritorial Obligations of States in the area of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 28 September 2011. http://www.maastrichtuniversity.nl/web/Institutes/MaastrichtCentreForHumanRights/MaastrichtETOPrinciples.htm

- International Monetary Fund. Regional economic outlook. Sub-Saharan Africa: April 2012. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/reo/2012/afr/eng/sreo0412.pdf

- Taskforce on Innovative International Financing for Health Systems. More Money for Health, and More Health for the Money. 2009. http://www.internationalhealthpartnership.net/fileadmin/uploads/ihp/Documents/Results___Evidence/HAE__results___lessons/Taskforce_report_EN.2009.pdf

- World Health Organization. World Health Report 2010. Health Systems Financing: The Path to Universal Coverage. 2010; WHO: Geneva. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/whr/2010/9789241564021_eng.pdf.

- J Sachs. Achieving universal health coverage in low-income settings. Lancet. 380(9845): 2012; 944–947.

- M Farag, AK Nandakumar, SS Wallack. Does funding from donors displace government spending for health in developing countries?. Health Affairs. 28(4): 2009; 1045–1055.

- C Lu, MT Schneider, P Gubbins. Public financing of health in developing countries: a cross-national systematic analysis. Lancet. 375(9723): 2010; 1375–1387.

- C Lane, A Glassman. Smooth and predictable aid for health: a role for innovative financing?. 2008; Brookings Institution: Washington, DC. http://www.brookings.edu/papers/2008/08_global_health_glassman.aspx.

- M Foster. Fiscal space and sustainability: towards a solution for the health sector. High-Level Forum for the Health MDGs, Selected papers 2003–2005. Geneva: WHO. 2005; World Bank: Washington, DC, 67. http://www.who.int/hdp/publications/hlf_volume_en.pdf.

- P Heller, Binding constraints on public funding: prospects for creating “fiscal space”. A Preker, M Linder, D Chernichovsky. Scaling Up Affordable Health Insurance: Staying the Course. 2013; World Bank: Washington, DC, 93.

- G Ooms, T Schrecker. Expenditure ceilings, multilateral financial institutions, and the health of poor populations. Lancet. 365(9473): 2005; 1821–1823.

- D Stuckler, S Basu, M McKee. International Monetary Fund and aid displacement. International Journal of Health Services. 41(1): 2011; 67–76.

- G Ooms, PS Hill, R Hammonds. Applying the principles of AIDS ‘exceptionality’ to global health: challenges for global health governance. Global Health Governance. 4(1): 2010; 1–9.

- LO Gostin, EA Friedman, G Ooms. The joint action and learning initiative: towards a global agreement on national and global responsibilities for health. PLoS Med. 8(5): 2011; e1001031.