Abstract

Understanding the flow of resources at the country level to reproductive health is essential for effective financing of this key component of health. This paper gives a comprehensive picture of the allocation of resources for reproductive health in Kenya and the challenges faced in the resource-tracking process. Data are drawn from Kenyan budget estimates, reproductive health accounts, and the Resource Flows Project database and compare budgets and spending in 2005–06 with 2009–10. Despite policies and programmes in place since 1994, services for family planning, maternity care and infant and child health face serious challenges. As regards health financing, the government spends less than the average in sub-Saharan Africa, while donor assistance and out-of-pocket expenditure for health are high. Donor assistance to Kenya has increased over the years, but the percentage of funds devoted to reproductive health is lower than it was in 2005. We recommend an increase in the budget and spending for reproductive health in order to achieve MDG targets on maternal mortality and universal access to reproductive health in Kenya. Safety nets for the poor are also needed to reduce the burden of spending by households. Lastly, we recommend the generation of more comprehensive reproductive health accounts on a regular basis.

Résumé

Pour financer efficacement la santé génésique, il est essentiel de comprendre le flux de ressources destinées, au niveau national, à cet élément clé de la santé. L’article brosse un tableau complet de l’allocation de ressources à la santé génésique au Kenya et les difficultés rencontrées dans le suivi des fonds. Les données sont tirées des estimations budgétaires kényanes, des comptes de la santé génésique et de la base de données sur le projet de flux de ressources. L’article compare les budgets et les dépenses de 2005–06 avec 2009–10. Bien que des politiques et programmes soient en place depuis 1994, les services de planification familiale, de soins maternels et de santé juvéno-infantile se heurtent à de sérieux écueils. S’agissant du financement de la santé, le Gouvernement dépense moins que la moyenne en Afrique subsaharienne, alors que l’assistance des donateurs et la participation des patients aux frais de santé sont élevées. L’aide des donateurs au Kenya a augmenté au fil des années, mais le pourcentage de fonds consacré à la santé génésique est inférieur à son niveau de 2005. Nous recommandons de relever le budget et les dépenses de santé génésique afin de réaliser les OMD sur la mortalité maternelle et l’accès généralisé à la santé génésique au Kenya. Des filets de sécurité pour les pauvres sont aussi requis afin de réduire la charge financière des ménages. Enfin, nous préconisons de créer régulièrement des comptes de santé génésique plus complets.

Resumen

Entender el flujo de recursos a nivel nacional en el área de salud reproductiva es esencial para la financiación eficaz de este elemento fundamental para la salud. En este artículo se ofrece una visión integral de la asignación de recursos para salud reproductiva en Kenia y los retos en el proceso de dar seguimiento a los recusos. Se obtuvieron datos de estimaciones presupuestarias, cuentas de salud reproductiva y la base de datos del Proyecto del Flujo de Recursos, y se compararon los presupuestos y los gastos en 2005–06 con los del 2009–10. A pesar de políticas y programas establecidos desde 1994, los servicios de planificación familiar, atención materna y salud de lactantes y de niños enfrentan retos difíciles. En la financiación de servicios de salud, el gobierno gasta menos del promedio en Ãfrica subsahariana, mientras que la asistencia de donantes y desembolsos varios para la salud son altos. En los últimos años, los donantes han aumentado su ayuda financiera a Kenia, pero el porcentaje de fondos dedicados a la salud reproductiva es menor que en 2005. Recomendamos un aumento en el presupuesto y los gastos en salud reproductiva a fin de lograr las metas de los ODM respecto a la mortalidad materna y el acceso universal a servicios de salud reproductiva en Kenia. Además, es necesario proteger a la gente pobre reduciendo la carga de gastos por vivienda. Por último, recomendamos generar con regularidad cuentas más integrales de salud reproductiva.

It is widely acknowledged that the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) can only be achieved if there are significant improvements in reproductive health, especially in the poorest developing countries, where most families still have more children than they want. Women especially suffer from the lack of means to control their fertility,Citation1 and many die young from causes related to maternal health.Citation2

The sub-Saharan African countries have made the fewest strides, especially as regards the MDG5 targets of reducing the maternal mortality ratio by three-quarters and achieving universal access to reproductive health. Statistics for the sub-Saharan African region indicate that the maternal mortality ratio declined from an average of 870 per 100,000 live births in 1990 to 640 per 100,000 births in 2008,Citation2 a reduction of only 26%. Huge improvements remain to be made for achieving universal access to antenatal care and family planning. The proportion of deliveries attended by skilled health personnel in the region slightly increased but remained low at 46% in 2009. The unmet need for contraceptives remained high at 25% in 2008.Citation2

During the ICPD+15 review meeting in Addis Ababa in 2009, over 70% of countries in sub-Saharan Africa indicated that they received insufficient external financial resources to successfully implement their population programmes, in particular those needed to achieve the MDG 5 targets.Citation3 A similar proportion faced the challenge of inadequate government funding. About 68% also indicated difficulties in mobilizing other domestic resources (both government and private resources). Some of the recommendations highlighted in the final reportCitation3 included:

increase technical and financial commitment of governments and development partners for the implementation of the MDGs and ICPD Programme of Action; | |||||

encourage the private sector to provide support for population and reproductive health programmes; | |||||

build institutional and human capacities for enhanced resource mobilization and contract negotiation skills within government agencies; | |||||

put in place national strategies, including partnership and coordination mechanisms, for better interaction between governments and all stakeholders, including NGOs and civil society for internal and external resource mobilization and monitoring of resource use, in support of population and reproductive health issues. | |||||

In light of the need for sufficient financing for better reproductive health outcomes, it is important for governments and donors to have accurate health financing information which compares funding needs with the allocation of resources (domestic and external), actual expenditure as well as projected availability of resources (domestic and external). The available information should respond to critical questions relating to the match between policy priorities and actual expenditures, and the predictability of funding for different reproductive health components as well as the availability of funds across the different levels of the health system. The reproductive health account (RHA) is one tool that can be used to generate this information. Generally conducted in tandem with the national health account (NHA), the reproductive health account is an additional, more detailed report of spending levels and patterns specific to reproductive health.Citation4 It is a comprehensive and consistent way to evaluate reproductive health expenditure data to help guide the allocation of limited resourcesCitation5–7 and inform reproductive health policy and programming. Yet only 22 countries in sub-Saharan Africa have successfully completed at least one round of national health accounts, and only a few countries, such as Kenya, Malawi, Rwanda, Namibia, Ethiopia and Uganda, have generated reproductive health (sub-) accounts.Citation8

This paper focuses on Kenya. It gives an overview of the reproductive health situation and the policy framework related to reproductive health. It then highlights the financial commitments of both the government and donors and expenditures to improve maternal and child health and to achieve universal access to reproductive health services. The problems facing reproductive health account estimation are also presented. Three main sources of data are used: Kenyan budget estimates, the Kenyan national health accounts for 2005–06 and 2008–09 and the UNFPA/NIDI Financial Resource Flows database. This analysis is part of the UNFPA endeavour to strengthen the resource tracking process and countries’ accountability to donors and civil society in sub-Saharan Africa through the Resource Flows Project. This paper aims to stimulate critical thinking about resource allocation for maternal health and other reproductive health activities in Kenya, both by the national government and the donors. We also hope that the recommendations for improving construction of a reproductive health account serve as a contribution to efforts by the Kenyan government and other sub-Saharan African governments to track the resources going to reproductive health in general.

Health and development indicators

Kenya’s population was estimated at 39 million in 2009 with a population growth rate of about 3%.Citation9 The country is classified among low human development countries with huge in-country differences and multidimensional poverty.Citation10

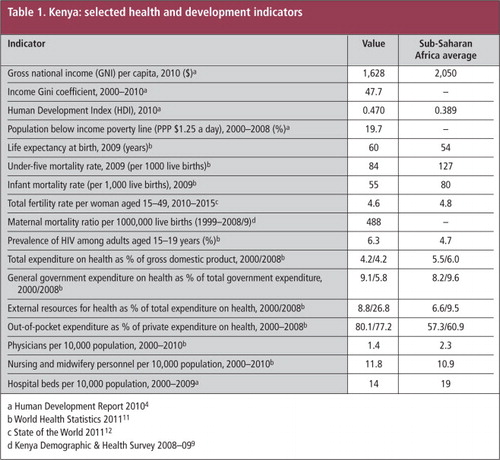

Table 1 presents selected development and health indicators for Kenya. While better off than many sub-Saharan Africa countries in terms of under-five and infant mortality,Citation9–12 the resources available for the health system, including physicians, nurses, midwives and hospital beds, are low. In health financing, Kenya spends less than the average of sub-Saharan African countries for health while donor assistance and out-of-pocket expenditure for health are generally high.

Reproductive and child health services package

Reproductive and child health care are generally combined in Kenya, in the context of motherhood. The package of reproductive health services includes the following components:

Family planning services to empower women to control the number and spacing of children, and related counselling, health education and information; | |||||

Maternal health services including antenatal and post-natal care to mothers and provision of dietary supplements for malnourished pregnant and lactating mothers; | |||||

Childbirth services; | |||||

Infant care to promote and improve the health and development of infants, including growth monitoring and promotion, and provision of dietary supplements such as micronutrients; | |||||

Child health services, including immunization; and | |||||

All other obstetric and gynaecological services to enable women to safely exercise their reproductive health functions. | |||||

Contraceptive prevalence (any method) among married women was estimated at 46% in 2008–09, with important urban-rural differences (53% urban and 43% rural).Citation9 Differences in contraceptive prevalence are also reflected in wealth quintiles (20% among women in the poorest quintile to 57% in the richest quintile. Moreover, the use of long-term methods such as intra-uterine devices and implants is negligible (around 2%).Citation9

Adequate maternity services and the availability of skilled personnel to attend to complications during delivery or from unsafe abortion still constitute serious challenges in Kenya. While the majority of pregnant women use antenatal care, less than 50% deliver with the assistance of skilled medical personnel.Citation9 The maternal mortality ratio has decreased from 590 per 100,000 live births prior to the 1998 Kenya Demographic & Health Survey (KDHS)Citation13 to 414 prior to the 2003 KDHS.Citation14 The ratio has subsequently increased again to 488 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in 2008–09,Citation9 far from the 2015 target of 147.

Reproductive health policy framework

Population and development have been identified since 1994 in Kenyan health policies as a priority strategy for achieving balanced socioeconomic development, including family planning, adolescent health and well-being of the entire family.Citation15 The goals include a reduced fertility rate, increased proportion of health facilities providing integrated reproductive health services and better access to and use of family planning services.

In response to the ICPD Programme of Action (1994), a national reproductive health strategy was adopted in 1997Citation16 with two objectives related to maternal health and universal access to reproductive health services: reduce maternal mortality to 170 by 2010 and increase professionally attended deliveries to 90%. The main elements of the strategy include improving facility capacity at all levels to manage pregnancy-related complications, unsafe abortion and newborn care and establishing a functioning referral system. The strategy was revised in 2009 with the adoption of the National Reproductive Health Strategy 2009–2015.Citation17 The need for revision was to address several issues and challenges not factored into the 1997 strategy and to provide clear guidance for implementation of the first National Reproductive Health Policy launched in 2007.

Other key initiatives undertaken by the government of Kenya to accelerate the reduction of maternal mortality include the Maternal and Newborn Health (MNH) Road Map 2010–2015. Launched in August 2010, the MNH Road Map identifies limited national commitment of resources for maternal and newborn health as one of the major reasons for slow progress in attaining the MNH targets.Citation18 For the implementation of the road map, the estimated additional cost for the period was Kshs. 2 billion (about US $24 million) in 2009–10, rising to Kshs. 3 billion (about US $36 million) in 2010–11 and Kshs. 4.1 billion (about US $49 million) in 2011–12. The costs were expected to start reducing thereafter.

The resource tracking process in Kenya

Kenya has undertaken four rounds of national health accounts (NHAs) (1994–95, 2001–02, 2005–06, and 2009–10). Reproductive health sub-accounts were estimated as part of the general health accounts during the 2005–06 and 2009–10 exercises. The process involves stakeholders in the health sector, especially those who constitute the Health Care Financing Task Force and those engaged in the Sector-Wide Approach (SWAp) process for an efficient use of the results. The national health account for the fiscal year 2005–06 was funded by the USAID/Kenya mission and government of Kenya whereas the one for 2009–10 was funded by the government of Kenya, USAID/Kenya, World Health Organization, and World Bank.

The results from these NHAs in Kenya are used to inform the preparation of the National Health Sector Strategic Plan (NHSSP) and to mobilise more funds for the health sector. The reproductive health accounts give key expenditure information for national policymakers, donors and other stakeholders, and guide strategic planning of reproductive health care. The first policy objective of the reproductive health account is to measure the following reproductive health indicators:

Total Health Expenditure on Reproductive Health (THERH), which aggregates reproductive health expenditure from public sources i.e. government expenditure on reproductive health (GERH) and private outlays on reproductive health; | |||||

Public/Government Expenditure on RH (GERH), which is made up of tax-funded reproductive health expenditure and Parastatal expenditures on reproductive health; | |||||

Donor expenditure on reproductive health, which aggregates expenditure from the rest of the world or external sources; | |||||

Social Security Expenditure on RH (SSERH), which is the proportion of total premium paid by employees and employers for compulsory schemes of health (medical) care and medical goods channelled to reproductive health care for a sizeable group of population, which is the expenditure of the National Hospital Insurance Fund (NHIF); | |||||

Ministry of Health Expenditures on Reproductive Health (MoH-ERH), which is expenditure channelled through the Ministry of Health or other public agencies; | |||||

Private Health Insurance Expenditure (PHIE), which represents the total of premiums collected from employers, households or sometimes other agents to prepay reproductive health-related medical and paramedical benefits, including the operating costs of these schemes; and | |||||

Out-of-Pocket Expenditure (OOP), which is direct outlays by households including gratuities and payments in-kind made to reproductive health practitioners and suppliers of medicines, therapeutic appliances, and other goods and services whose primary intent is to improve the reproductive health status of individuals or population groups. | |||||

The second policy objective is to articulate the distribution of reproductive health expenditures by use. The third policy objective is to analyze efficiency, equity, and sustainability issues associated with the health care financing and expenditures patterns.

Key findings from the Kenyan reproductive health accounts

Reproductive health financing sources

Our analysis indicates that the total health expenditure on reproductive health (THERH) increased from Kshs 12.9 billion (US $170.4 million) in 2005–06 to Kshs 17 billion (US $225.2 million) in 2009–10. The public sector contributed 34% of the THERH in 2005–06 and 40% in 2009–10.

Out-of-pocket household payments contributed 38% of the THERH in 2005–06, which dropped to 29% in 2009–10, which is still very high. The private sector contributed only 3% in 2005–06 and 1% in 2009–10, while donors contributed 24% and 22% of the total in 2005–06 and 2009–10, respectively.

Thus, consumers bear a disproportionate share when it comes to reproductive health and family planning expenditures in Kenya. As a percentage of total out of pocket expenditure on general health, households spent 14% on reproductive health services in 2009–10 as opposed to 10% in 2005–06. Out-of-pocket spending, especially by the poor, has important implications for policy initiatives aimed at reducing poverty and inequities in health access in Kenya.

Reproductive health financing agents

Financing agents are public or private entities which pull money from financing sources to pay directly for health care. The statistics on this are different from those above on financing sources.Footnote* Overall, 46.7% of reproductive health financial resources passed through public entities, specifically, the Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation and the Ministry of Medical Services in 2009–10, as compared to 45.7% in 2005–06. Households, through out-of-pocket spending, channelled 19.3% of reproductive health financial resources in 2009–10, down from 26.3% in 2005–06. Private insurance entities channelled 9.3 % in 2005–06 and 13% in 2009–10, and NGOs channelled 1.6% in 2005–06 and 9.4% in 2009–10, while the public National Hospital Insurance Fund channelled 6.2% in 2005–06 and 8.8% in 2009–10.

Distribution of reproductive health expenditure by activities

The Kenya NHAs of 2005–06 and 2009–10 do not give estimates of expenditure by broad components of reproductive health care, but the estimates are broken down into curative (inpatient and outpatient), preventive (antenatal and post-natal, family planning service delivery) and rehabilitative elements. The findings indicate that outpatient curative care consumed the largest share of total health expenditure on reproductive health, at 41% in 2009–10, up from 25% reported in 2005–06. Inpatient curative care that includes deliveries and sterilizations, as well as other services that could not be disaggregated, accounted for 30% of the total health expenditure on reproductive health in 2009–10 down from 62% in 2005–06.

Spending on family planning commodities

The reproductive health account estimates for 2005–06 and 2009–10 underestimate the resources going to family planning commodities, mainly because they rely on distributional factors/ratios to apportion reproductive health expenditures by activity. However, it is worth noting that when the two periods are compared, the resources going to family planning commodities increased in absolute terms from Kshs 13 million to 171 million (US $172,000 to US $2.3 million). Contraceptive prevalence has indeed increased (by at least four percentage points) during the period, justifying this huge increase in spending. USAID estimates indicate that Kenya will need to spend approximately Kshs 672 million (about US $8.3 million) on family planning commodities and direct personnel costs to provide services at government facilities for all methods by 2015.Citation19

Coverage by health insurance

Coverage by health insurance in Kenya is limited both in terms of the numbers covered and the resources controlled by the insurance sector – National Hospital Insurance Fund (NHIF) and private health insurance. In 2005–06, private health insurance controlled 9.3% of the total expenditures on RH compared to 12.5% in 2009–10. NHIF alone controlled 6.2% of total RH resources in 2005–06 as opposed to 8.8% in 2009–10. In total, health insurance accounted for 21.3% of resources mobilized for reproductive health in 2009–10, up from 15.5% in 2005–06.

National commitments for maternal, newborn and child health

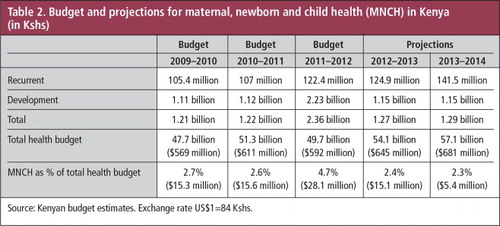

Kenya’s maternal, newborn and child health sector has received little attention as far as budget allocation is concerned, despite MDG 5. As shown in Table 2, maternal, newborn and child health accounts for less than 5% of the total health budget and this percentage has fluctuated over the years from 2.7% in 2009–10 to 4.7% in 2011–12. The projections for 2013–14 indicate a lower percentage of 2.3%.

The recurrent budget shown in Table 2 is built upon estimated numbers and is used to cushion the government in case revenues come in low. It includes revenue from taxes and loans and is used to cover operational costs such as salaries, utilities and maintenance. The development budget comprises funding assigned for development purposes and includes funds from the development partners. The development budget and projections include external resources that go through the Kenya budget system (on-budget).

If in fact US $49 million were needed in 2011 for the implementation of the Maternal and Newborn Health Road Map, as the government calculated,Citation18 even if the costs were less thereafter, the current budget projections would likely cover only half the costs. This means that, unless a strong commitment is made to increase the budget for reproductive health in general (and maternal and child health services in particular), a cost-sharing policy is the most likely way to bridge the gap between the national budgets and the level of resources needed to fund these reproductive health activities. A “cost-sharing” policy was implemented by the Kenyan government in 2004 in which services at public health facilities became free for all citizens, except for a minimum registration fee of Kshs 10–20 (US $0.12 – 0.23).Citation20,21 A reality check in fact showed that the contribution of user fees for reproductive health services in various health districts was disproportionally higher than the government’s own financial contribution.Citation20 This has huge implications for the financial burden of reproductive health expenditures on households, especially in a context of increased poverty.

Trends in donor assistance to Kenya

Kenya is one of the countries in sub-Saharan Africa that receives constant and important funding for the health sector from various donors,Citation22,23 including several like-minded European donors.Citation23 The assessment of official development assistance for maternal, newborn, and child health under the Countdown to 2015 Initiative indicates that Kenya is one of the priority countries for this assistance.Citation24

We used the UNFPA/NIDI Financial Resource Flows data base (http://www.resourceflows.org) to examine the size and structure of donor funding for reproductive health activities to Kenya over the years. The UNFPA/NIDI Resource Flows Project uses the ICPD costed-population package categories for collecting annual data on donor funding. These categories include: family planning, basic reproductive health services, prevention and treatment of STIs and HIV/AIDS, and basic research. Information about the funding level from donors for these four categories of activities has been collected by the UNFPA/NIDI Resource Flows Project since 1996. We limited our analysis to data collected from 2005 to 2010 since comparative information about the Kenya budget for reproductive health activities is available only for 2005–06 and 2009–10.

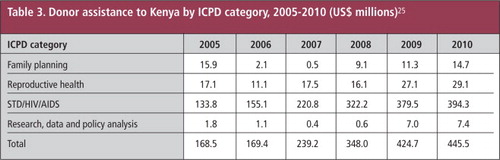

Table 3 shows that there has been a continuous increase in donor assistance for the four categories over the years, from US $168.5 million in 2005 to US $445.4 million in 2010. This amount includes assistance from developed countries, the United Nations system, foundations, NGOs, and development bank grants. However, as Table 3 indicates, most of the funding from donors and the increments are for HIV/AIDS projects (i.e. prevention, mass media and in-school education, promotion of voluntary abstinence and responsible sexual behaviour and expanded distribution of condoms). Donor assistance to Kenya specifically for basic reproductive health activities (i.e. information and routine services for antenatal, delivery and postnatal care, education and communication about reproductive health including HIV/AIDS) has fluctuated between US $11.1 million and US $29.1 million over the period. In absolute dollar amounts, donor assistance for basic reproductive health activities increased (from US $17.1 million in 2005 to US $29.1 million in 2010) but the percentage of donor assistance devoted to basic reproductive health activities in 2010 (6.5%) was lower than it was in 2005 (10.1%).

Table 3 also indicates that donor assistance to Kenya for family planning services in particular (including contraceptive commodities and service delivery, education and communication) was drastically reduced between 2005 and 2007, from US $15.9 million in 2005 to US $0.5 million in 2007. This reduction was observed in most sub-Saharan African countries because priority for family planning had dropped down the priority list of international development during this period.Citation26 Donor assistance for family planning has nevertheless increased since 2008 and the figures indicate a total amount of US $14.5 million in 2010.

Major challenges facing reproductive health account estimations in Kenya and the way forward

In spite of the extensive work undertaken by the national health account team, using international standards for health accounts, the reproductive health account process in Kenya faces three major challenges. The first is the fact that the budget for reproductive health activities could not be broken down by service element, i.e. by family planning, maternal health services, delivery services and infant care, child health services and management of other reproductive health problems. For future reproductive health expenditure analysis, and to ensure a feasible breakdown of reproductive health expenditure, we recommend a costing study at health facility level as part of the reproductive health accounts. In this way, resources spent on reproductive health from the financing agents can be broken down into these reproductive health components. Another way of breaking down the reproductive health expenditure at the national level is to take advantage of key informants (expert opinion) among those managing reproductive health resources at that level – the department of reproductive health in Kenya’s case – to find out what proportion of the budget is attributed to the different components.

The second major challenge facing reproductive health account estimation in Kenya is the lack of comprehensive data to estimate out-of-pocket spending on reproductive health. There is increasing evidence that out-of-pocket expenses act as a financial barrier to essential health care. They are a source of impoverishment and ill health and can exacerbate inequity.Citation27,28 They may force households to reduce expenditure on other essential items, such as food, and rely on risky coping strategies. This applies particularly to catastrophic expenditures, i.e. expenditures that use a significant proportion of the household budget. Out-of-pocket expenses have proved to be one of the components with least reliability in most health accounts.Citation29 It is also recognized that out-of-pocket expenses are the largest or second largest source of health care financing in developing countries, on one hand, and the largest source of error estimates of national health spending, on the other hand.Citation29 Guidance is thus required to promote best practice in the identification of available data sources. The available data for estimating the role of households were not sufficient to estimate out-of-pocket spending on reproductive health in the Kenyan reproductive health accounts. The team ended up using distributive variables like utilization statistics and unit costs to derive some estimates of out-of-pocket spending, but they may have been under-estimated or over-estimated. A special Household Health Expenditure and Utilization Survey (HHEUS) targeting reproductive health services will therefore be required in future to obtain a robust estimate of this type of out-of-pocket spending in Kenya.

The third major challenge is the lack of information on spending on reproductive health by beneficiaries, rendering it impossible to generate a Benefit Incidence Analysis that shows who benefits from reproductive health spending. The benefit incidence analysis is a tool that investigates the extent to which the financial benefits of public spending on social services accrue to different population groups (e.g. the poor, adolescents, older women and men).Citation30,31 Benefit-incidence analyses have long been used in the public finance field, to determine who benefits from public spending on specific programmes. The socio-economic status and health status of beneficiaries are of particular importance in the analysis of reproductive health expenditures. Vulnerability status is also an important concept for reproductive health accounts. Vulnerable groups include women or couples who want to limit or space children but have no access to the means to do so, and adolescents. The breakdown of reproductive health spending by beneficiary groups is one of the most challenging health accounts activities.Citation4 It requires reliable health status and population data that can be linked to reproductive health expenditures. In the 2005–06 and 2009–10 reproductive health accounts, these could not be generated due to a lack of reliable data on utilization of reproductive health services. However, an analysis of who benefited from expenditures on general health was undertaken as household utilization of general health services using data from the Household Health Expenditure and Utilization Surveys of 2007. To generate the reproductive health spending by beneficiaries, statistics on reproductive health services use need to be generated alongside the reproductive health account estimations.

Discussion and recommendations

Maternal and child health remain a major public health problem facing Kenya. Maternal mortality has remained high and was estimated to be at 488 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in 2009–10, far from the MDG target of 147 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births.Citation9 Kenya is also far from reaching the MDG target of universal access to reproductive health. Less than 50% of women deliver with the assistance of skilled medical personnel, and the unmet need for family planning remains high at 30% among young people aged 15–24.Citation9

Many reproductive health priorities, such as improving service quality and patient satisfaction, educating patients and providing more choices, are consistent with health sector reforms in Kenya. However, in terms of increasing resources for reproductive health, not much has been achieved. As regards funding on health in general, Kenya is doing poorly when compared to its neighbours or the sub-Saharan Africa average.Citation20,32 Kenya is a signatory of the Abuja Declaration which pledges to increase African governments’ spending for health to at least 15% of the total budget, but this commitment remains to be met.Footnote* The Kenyan government’s health expenditure as a percentage of total government expenditure significantly declined from 8.6% in 2001–02 to 4.6% in 2010–11. The trend differs from other East African countries, such as Tanzania, Uganda and Ethiopia, who spend comparatively more on health as a percentage of government expenditure.Citation32

Kenya spent a total of US $225.2 million for reproductive health services in 2009–10,Citation33 suggesting that a lot of effort will have to be made by the government to mobilise domestic resources to fund the much-needed programmes or to advocate for more funds from donors. With regard to family planning services in particular, substantial investments (about US$8.3 million) are needed by 2015 for providing commodities and covering personnel costs at government facilities. Kenya must capitalize upon the growing momentumFootnote† around family planning issues to establish voluntary family planning programmes as accepted, expected, and routine elements of the national health care system.

The reduction of out-of-pocket spending on reproductive health services should also be a key policy goal in Kenya. Data from the 2008–09 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey indicate that households still list cost as a leading barrier to their use of essential services.Citation9 Various initiatives are being undertaken by the government of Kenya to reduce both per capita out-of-pocket spending by households as well as the share of total health funding contributed by households. These include cost-sharing policies and programmes, such as the Health Sector Services Fund, the output-based approach and the Joint Programme of Work and Funding. These initiatives particularly aim to enhance the access to health financial resources by the poor and vulnerable. Recent evaluations of the output-based approach in Kenya indicated, for instance, that the uptake of skilled attendance at delivery (including normal delivery and caesarean section), as measured by redeemed vouchers, increased to 77% of vouchers provided.Citation33,34 Such initiatives should be carried out along with further investments to harness out-of-pocket spending into more efficient uses, such as health insurance. This requires a strong commitment from both development partners and the government to increase and strengthen spending on reproductive health services.

Finally, we recommend generation of more comprehensive reproductive health accounts data on a regular basis in Kenya. Improvements in reproductive health services require significant resource commitments as well as efficient and effective use of those resources. National decision-makers need to know whether their country has adequate resources to achieve their reproductive health goals. They also need to be accountable to donors, civil society and the United Nations. African governments often lack the technical instruments needed to plan for adequate budgets. Kenya has succeeded with a few other countries in sub-Saharan Africa to complete more than one round of national health accounts that include reproductive health sub-accounts. This could be achieved by all sub-Saharan countries with adequate technical and financial support from both governments and development partners. We recognize that data on resources going to reproductive health at the country level in Kenya are available, but the quality needs to be improved. The reproductive health account estimation process in Kenya suffers from a lack of data on expenditure by service element. The available data are also not sufficient to estimate households’ out-of-pocket spending. Furthermore, information on spending on reproductive health by beneficiaries is missing, rendering it impossible to generate an analysis of who benefits from reproductive health spending. In sum, our recommendations include:

undertaking a costing study of reproductive health services at the facility/provider level, | |||||

undertaking household health expenditure and utilization surveys targeting reproductive health services to gain robust information on out-of-pocket spending, and | |||||

expanding national health accounts teams to include representatives of key NGOs and development partners. | |||||

Acknowledgments

The study is part of the Resource Flows Project run in collaboration between UNFPA, the Netherlands Interdisciplinary Demographic Institute and the African Population and Health Research Centre. The aim of the Resource Flows project is to monitor global financial flows for population and HIV/AIDS activities, and to strengthen the institutionalization of country-owned systems to produce periodic reports that compare the need for sexual and reproductive health funding at country level with the allocation of resources (domestic and external). The views expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of UNFPA, NIDI or APHRC.

Notes

* Households, for instance, paid for 29% of health care in 2009–10 but channelled only 19.3% directly to providers; this is because their money is not necessarily paid directly to the providers but through public or private insurance funds.

* In April 2001, African Union countries meeting in Abuja, Nigeria, pledged to increase government funding for health to at least 15%, and urged donor countries to scale up support. http://www.who.int/healthsystems/publications/abuja_report_aug_2011.pdf.

† Recent meetings included the International Family Planning Conferences in 2009 in Kampala, 2011 in Dakar, and 2012 in London, which attracted large audiences from around the world uniting global leaders around new funding commitments.

References

- L Alkema, V Kantorova, C Menozzi. National, regional, and global rates and trends in contraceptive prevalence and unmet need for family planning between 1990 and 2015: a systematic and comprehensive analysis. Lancet. 381: 2013; 1642–1652.

- United Nations. The Millennium Development Goals Report 2011. 2011; UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York.

- United Nations Economic Commission for Africa UNFPA Africa Union Commission. Africa Regional Review Report, ICPD and the MDGs: Working as One. Fifteen-Year Review of the Implementation of the ICPD Programme of Action in Africa–ICPD at 15 (1994–2009). ECA/ACGS/HSD/ICPD/RP/2009. 2009; ECA: Addis Ababa.

- World Health Organization. Guide to producing national health accounts. With special applications for low-income and middle-income countries. 2003; WHO: Geneva. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2003/9241546077.pdf.

- De S, Hatt L. Reproductive and child health subaccounts to track resource allocations and flows. Presentation at Scaling-Up High Impact FP/MNCH Best Practices, Bangkok, 4 September 2007.

- S De. Importance of NHA Subaccounts; and USAID. Using reproductive health subaccounts to advocate for increased resources for family planning. Repositioning in Action E-Bulletin. August 2008. www.usaid.gov/our_work/global_health/pop/techareas/repositioning/repfp_ebulletin/080808_en.html

- USAID. Using reproductive health subaccounts to advocate for increased resources for family planning, and Health Systems 20/20 Project, National Health Accounts Subaccounts: Tracking Health Expenditures to Meet the Millennium Development Goals, Project Brief, 2009.

- World Health Organization. National health accounts: country health information. http://www.who.int/nha/country/en/

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics ICF Macro. Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2008–09. Calverton MD: KNBS and ICF Macro; 2010. See also Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. Kenya Population and Housing Census highlights 2009. http://www.knbs.or.ke/Census/20Results/KNBS/20Brochure.pdf

- United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report 2010: The real wealth of nations-pathways to human development. 2010; UNDP: New York.

- World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2011. 2011; WHO: Geneva.

- United Nations Population Fund. State of the World 2011. People and Possibilities in a World of 7 Billion. 2011; UNFPA: New York.

- National Council for Population and Development Central Bureau of Statistics (Office of the Vice President and Ministry of Planning and National Development, Kenya) Macro International. Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 1998. 1999; NCPD &Macro International: Calverton MD.

- Central Bureau of Statistics Ministry of Health ORC Macro. Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2003. 2004; Central Bureau of Statistics and ORC Macro: Calverton MD.

- Republic of Kenya, Ministry of Health. Kenya Health Policy Framework. Nairobi; 1994. See also: Republic of Kenya, Ministries of Health. Kenya Health Policy 2012–2030. 2012; Ministry of Health: Nairobi.

- Republic of Kenya, Ministry of Health. National Reproductive Health Strategy 1997–2010. 1994; Ministry of Health: Nairobi.

- Republic of Kenya, Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation & Ministry of Medical Services. National Reproductive Health Strategy 2009–2015. 2009; Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation; Ministry of Medical Services: Nairobi.

- Republic of Kenya. National road map for accelerating the attainment of the MDGs related to maternal and newborn health in Kenya. 2010; Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation; Ministry of Medical Services: Nairobi.

- USAID. The cost of family planning in Kenya. http://www.healthpolicyinitiative.com/Publications/Documents/1189_1_1189_1_Kenya_Brief_FINAL_7_12_10_acc.pdf

- German Foundation for World Population (DSW) and Institute for Education in Democracy. 2011. Health financing in Kenya: the case of RH/FP. 2011; DSW/IED: Nairobi.

- J Chuma, J Musimbi, V Okungu. Reducing user fees for primary health care in Kenya: policy on paper or policy in practice?. International Journal of Equity in Health. 8: 2009; 15.

- S Seims. Improving the impact of sexual and reproductive health development assistance from the like-minded European donors. Reproductive Health Matters. 19: 2011; 129–140.

- N Ravishankar, P Gubbins, RJ Cooley. Financing of global health: tracking development assistance for health from 1990 to 2007. Lancet. 373: 2009; 2113–2124.

- C Pitt, G Greco, T Powell-Jackson. Countdown to 2015: assessment of official development assistance to maternal, newborn, and child health, 2003–08. Lancet. 376: 2010; 1485–1496.

- UNFPA/NIDI. Financial Resource Flows database. http://www.resourceflows.org

- J Cleland, S Bernstein, A Ezeh. Family planning: the unfinished agenda. Lancet Sexual and Reproductive Health Series. 368(9549): 2006; 1810–1812.

- L Demery. Analyzing the incidence of public spending. F Bourgignon, LA Pereira da Silva. The Impact of Economic Policies on Poverty and Income Distribution. 2003; World Bank, Oxford University: New York.

- D Van de Walle. Behavioral incidence analysis of public spending and social programs. F Bourgignon, LA Pereira da Silva. The Impact of Economic Policies on Poverty and Income Distribution. 2003; World Bank, Oxford University: New York.

- RP Rannan-Eliya. Estimating out-of-pocket spending for national health accounts. 2010; World Health Organization: Geneva. http://www.who.int/nha/methods/estimating_OOPs_ravi_final.pdf.

- E van Doorslaer. Effects of payments for health care on poverty estimates in 11 countries in Asia: an analysis of household survey data. Lancet. 368: 2006; 1357–1364.

- I Anderson, H Axelson, B-K Tan. The other crisis: the economics and financing of maternal, newborn and child health in Asia. Health Policy and Planning. 26: 2011; 266–297.

- Republic of Kenya, Ministry of Medical Services, Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation. Advancing Progress in an era of growth: raising public commitments to Kenya’s health sector. Policy Brief. 2011.

- Republic of Kenya, Ministry of Medical Services, Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation. Kenya National Health Accounts 2009/10.

- Republic of Kenya, National Coordinating Agency for Population & Development. An output-based approach to reproductive health: vouchers for health in Kenya. NCAPD Policy Brief No. 2. 2008; NCAPD: Nairobi.