Foreword

The adoption by consensus of the United Nations General Assembly resolution Intensifying global efforts for the elimination of female genital mutilations in December 2012 is a testimony to the increased commitment by all countries to end this harmful practice. Evidence played a major part in bringing the resolution to fruition, and it will continue to play a central role in global efforts to eliminate the practice.

Evidence on female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) is essential for many reasons – to understand not only the extent of the practice but also to discern where and how the practice is changing. It helps us understand the social dynamics that perpetuate FGM/C and those that contribute to its decline… so that policies and programmes can be effectively designed, implemented and monitored to promote its abandonment.

The collection and analysis of data is a central aspect of UNICEF’s mission to enable governments and civil society to improve the lives of children and safeguard their rights. This report, Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: A statistical overview and exploration of the dynamics of change, promotes a better understanding of the practice in several ways. It examines the largest ever number of nationally representative surveys from all 29 countries where FGM/C is concentrated, including 17 new surveys undertaken in the last three years. It includes new data on girls under 15 years of age, providing insights on the most recent dynamics surrounding FGM/C, while also presenting estimates on prevalence and levels of support for the practice nationally and among selected population groups. A special feature of the report is that it explores the data through the lens of social norms and looks at the ways in which they affect the practice.

Working with a multitude of partners, including through the UNFPA-UNICEF Joint Programme on Female Genital Mutilation/ Cutting: Accelerating Change, we have seen how social dynamics can be leveraged to help communities better protect their girls. We have witnessed how accurate information about the dangers of the practice as well as evidence that other communities are questioning or abandoning FGM/C can spark or invigorate a process of positive change. We have witnessed how the voices of individuals and groups who have themselves abandoned the practice can fuel further positive action. And we have seen how girls themselves can play a catalytic role. Learning from these experiences, we have strengthened our support to communities by creating opportunities for discussion on FGM/C locally and nationally. The abandonment of FGM/C is framed not as a criticism of local culture but as a better way to attain the core positive values that underlie tradition and religion, including ‘doing no harm to others’. We have found that, addressed in this way, efforts to end FGM/C contribute to the larger issues of ending violence against children and women and confronting gender inequalities.

UNICEF published its first statistical exploration of FGM/C in 2005, helping to increase awareness of the magnitude and persistence of the practice. This report, published eight years later, casts additional light on how the practice is changing and on the progress being made. The analyses contained on the following pages show that social dynamics favouring the elimination of the practice may exist even in countries where the practice is universal and provide clues on how they might be harnessed. The report also makes clear that, in some countries, little or no change is apparent yet and further programmatic investments are needed.

As many as 30 million girls are at risk of being cut over the next decade if current trends persist. UNICEF will continue to engage with governments and civil society, together with other partners, to advance efforts to eliminate FGM/C worldwide. If, in the next decade, we work together to apply the wealth of evidence at our disposal, we will see major progress. That means a better life and more hopeful prospects for millions of girls and women, their families and entire communities.

Geeta Rao Gupta

Deputy Executive Director, UNICEF

Moving forward

Obtaining timely, comparable and reliable information on FGM/C is a key aspect of efforts aimed at promoting its elimination. The wealth of information available in this report can be used by governments, international agencies, civil society and other development partners to fine-tune strategies seeking to encourage the abandonment of the practice. The practice of FGM/C has proven remarkably tenacious, despite attempts spanning nearly a century to eliminate it. Nevertheless, the data in this report show that the practice has declined in a number of countries, and other changes are also under way. These changes, which include shifts in attitudes and in the way the procedure is carried out, are taking place at different speeds across population groups. The data also indicate that, in other countries, FGM/C remains virtually unchanged.

Due to time lags inherent in the practice itself and in monitoring it, the results of intensified efforts to address FGM/C over the last decade cannot yet be fully assessed. That said, an analysis of the current data reveals patterns that allow us to draw some general conclusions about the changing nature of the practice. These patterns also confirm the understanding of the social dynamics that underlie FGM/C and help to explain its persistence. These findings can be used to further strengthen and refine programmes and policies aimed at eliminating this harmful practice.

Key findings

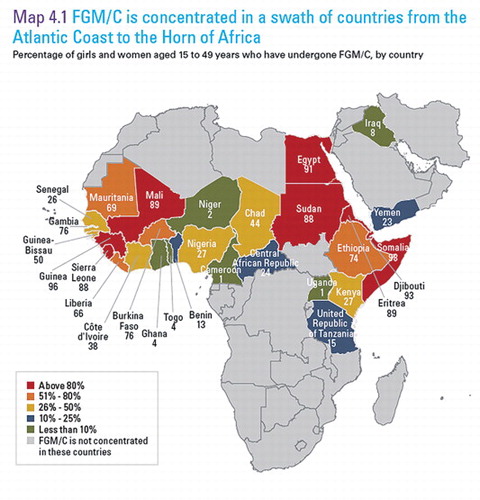

More than 125 million girls and women alive today have undergone some form of FGM/C in a swath of 29 countries across Africa and the Middle East. Another 30 million girls are at risk of being cut in the next decade. The practice is found to a far lesser degree in other parts of the world, though the exact number of girls and women affected is unknown.

While FGM/C is nearly universal in Somalia, Guinea, Djibouti and Egypt, it affects only 1 per cent of girls and women in Cameroon and Uganda. In countries where FGM/C is not widespread, it tends to be concentrated in specific regions of a country and is not constrained by national borders. FGM/C is closely associated with certain ethnic groups, suggesting that social norms and expectations within communities of like-minded individuals play a strong role in the perpetuation of the practice. In many countries, prevalence is highest among Muslim girls and women. However, the practice is also found among other religious communities. In four out of 14 countries with available data, more than 50 per cent of girls and women regard FGM/C as a religious requirement.

FGM/C is usually performed by traditional practitioners. In countries including Egypt, Kenya and Sudan, a substantial proportion of health-care providers carry out the procedure. Available trend data show that, in Egypt, where the medicalization of FGM/C is most acute, the percentage of girls cut by health personnel increased from 55 per cent in 1995 to 77 per cent in 2008.

In half of the countries with available data, the majority of girls are cut before the age of five. In Somalia, Egypt, Chad and the Central African Republic, at least 80 per cent of girls are cut between the ages of 5 and 14, sometimes in connection with coming-of-age rituals marking the passage to adulthood.

Hela Bakri, 31, sits with her 15-year-old daughter, Neshwa Sa’ad, in theirhome in the Abu Si’id neighbourhood of Omdurman, a city in KhartoumState, Sudan. Hela dropped out of school at age 10, shortly after she wassubjected to FGM/C. She has sent all three of her daughters to primaryschool, and is saving money to send Neshwa to secondary school. “I wantNeshwa to have all of the education that she can because I missed out onthat,” said Hela. Years ago, Neshwa was cut even though Hela opposesthe procedure. “I didn’t have any choice…. I boycotted the celebrationsafterwards because I wasn’t in agreement.” She hopes to keep hertwo younger daughters from experiencing FGM/C.

Most mothers whose daughters have undergone FGM/C report that the procedure entailed the cutting and removal of some flesh from the genitalia. In Somalia, Eritrea, Niger, Djibouti and Senegal, more than one in five girls have undergone the most radical form of the practice known as infibulation, which involves the cutting and sewing of the genitalia. Overall, little change is seen in the type of FGM/C performed across generations. A trend towards less severe cutting is discernible in some countries, including Djibouti, where 83 per cent of women aged 45 to 49 reported being sewn closed, versus 42 per cent of girls aged 15 to 19.

Trend data show that the practice is becoming less common in more than half of the 29 countries. The decline is particularly striking in some moderately low to very low prevalence countries. In Kenya and the United Republic of Tanzania, for example, women aged 45 to 49 are approximately three times more likely to have been cut than girls aged 15 to 19. In Benin, Central African Republic, Iraq, Liberia and Nigeria, prevalence has dropped by about half among adolescent girls. In the highest prevalence regions of Ghana and Togo, respectively, 60 per cent and 28 per cent of women aged 45 to 49 have undergone FGM/C compared to 16 per cent and 3 per cent of girls aged 15 to 19.

Some evidence of decline can also be found in certain high prevalence countries. In Burkina Faso and Ethiopia, the prevalence among girls aged 15 to 19 compared to women aged 45 to 49 has dropped by 31 and 19 percentage points, respectively. Egypt, Eritrea, Guinea, Mauritania and Sierra Leone have registered smaller declines. In a few countries, new data on girls under 15 years of age seem to confirm an important trend towards the elimination of the practice in recent years. In countries such as the Central African Republic and Kenya, the drop in prevalence has been constant over at least three generations of women and appears to have started four to five decades ago. In other countries, including Burkina Faso, the decline appears to have started or accelerated over about the last 20 years. No significant changes in FGM/C prevalence can be observed in Chad, Djibouti, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Senegal, Somalia, Sudan and Yemen.

The data reveal that FGM/C often persists in spite of individual preferences to stop it. In most countries where FGM/C is practised, the majority of girls and women think it should end. Moreover, the percentage of females who support the practice is substantially lower than the share of girls and women who have been cut, even in countries where FGM/C prevalence is very high. The largest differences in prevalence and support are found in Burkina Faso, Djibouti, Sudan, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Egypt and Somalia.

In 11 countries with available data, at least 10 per cent of girls and women who have been cut say they see no benefits to the practice. The proportion reaches nearly 50 per cent in Benin and Burkina Faso, and 59 per cent in Kenya. Not surprisingly, the chances that a girl will be cut are considerably higher when her mother favours the continuation of the practice.

The attitudes of men and women towards FGM/C are more similar than conventional wisdom would suggest. Genital cutting is often assumed to be a manifestation of patriarchal control over women, suggesting that men would be strong supporters of the practice. In fact, a similar level of support for FGM/C is found among both women and men. In Guinea, Sierra Leone and Chad, substantially more men than women want FGM/C to end.

Marriageability is often posited as a motivating factor in FGM/C. This may have been true at one time. However, with the exception of Eritrea and Sierra Leone, relatively few women report concern over marriage prospects as a justification for FGM/C. Preserving virginity, which may be indirectly related to marriageability, was among the more common responses in women in Mauritania, Gambia, Senegal, Mali and Nigeria. The responses of boys and men to questions regarding the possible benefits of the practice largely mirrored those given by girls and women, with social acceptance and preservation of virginity being the most commonly cited reasons in most countries.

When attitudes are tracked over time, it appears that overall support for the practice is declining, even in countries where FGM/C is almost universal, such as Egypt and Sudan. Data show that in nearly all countries with moderately high to very low prevalence, the percentage of girls and women who report that they want the practice to continue has steadily declined. In the Central African Republic, for instance, the proportion of girls and women who support the practice has continued to fall – from 30 per cent to 11 per cent in about 15 years. In Niger, the share dropped from 32 per cent to 3 per cent between 1998 and 2006. There are, however, exceptions: the proportion of girls and women who reportedly want FGM/C to continue has remained constant in countries including Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Senegal and the United Republic of Tanzania.

Implications for programming

Take into account differences among population groups within and across national borders

When national data on FGM/C are disaggregated by region and by ethnicity, it becomes clear that changes in the practice vary according to population groups. This is consistent with the notion that specific social dynamics are at play within different communities. In Kenya, for instance, FGM/C has declined steadily among certain ethnic groups where it was once almost universal and has persisted among others. In the space of three generations, the practice has become rare among the Kalenjin and Kikuyu, and has almost disappeared among the Meru. At the same time, more than 95 per cent of Somali and Kisii girls are still being cut.

These findings suggest that national plans to eliminate FGM/C should not apply uniform strategies in all parts of a country. Rather, they need to consider the specificity of various groups that share ethnicity or other characteristics. These groups may be concentrated in certain geographic regions of a country or extend across national borders. In the latter case, collaboration with neighbouring countries and with members of the diaspora may be required.

In particular, strategies need to consider both the degree of and trends in support for FGM/C and prevalence among different population groups. Where positive transformation is occurring rapidly, it can potentially be leveraged to encourage change elsewhere, as explained below. Strategies may also need to be adjusted over time to reflect changes in the practice within specific groups. Focused attention may be needed among communities where little or no change in the practice is evident.

Seek change in individual attitudes about FGM/C, but also address expectations surrounding the practice within the larger social group

A review of trends in attitudes towards FGM/C and prevalence suggests that diminishing support tends to precede an actual decline in the practice. To influence individual attitudes, it is important to continue to raise awareness that ending FGM/C will improve the health and well-being of girls and women and safeguard their human rights. At the same time, legislative action is critical, especially as an instrument to decrease support for FGM/C, including by highlighting the legal consequences of engaging in the practice. Also essential are efforts to correct the misconception that FGM/C is required by religion. In numerous countries, religious leaders and scholars are attempting to ‘delink’ FGM/C from religion. In Sudan, a national campaign portrays the uncut girl as whole, intact, unharmed, pristine – in other words, in perfect, God-given condition.

While shifts in individual attitudes are important, the data also show that they do not automatically lead to behaviour change. Across countries, many cut girls have mothers who oppose the practice. This indicates that other factors, which may include expectations within the larger social group, prevent women from acting in accordance with their personal preferences. Data also reveal that the most commonly reported reason for carrying out FGM/C is a sense of social obligation. This provides further evidence that the practice is relational and that the behaviour of individuals is conditioned by what others they care about expect them to do.

All of these findings suggest that efforts to end the practice need to go beyond a shift in individual attitudes and address entire communities in ways that can decrease social expectations to perform FGM/C. Such a collective approach may be necessary to generate the shift in social norms required to catalyse changes in the practice of FGM/C and could help bring down prevalence levels more rapidly.

Find ways to make hidden attitudes favouring the abandonment of the practice more visible

Discrepancies between declining support for FGM/C and the continuation of the practice suggest that attitudes about genital cutting tend to be kept in the private sphere. Opening the practice up to public scrutiny in a respectful manner, as is being done in many programmes throughout Africa, can provide the spark for community-wide change. For decades, programmatic efforts have actively promoted pronouncements by respected and influential personalities, including traditional and religious leaders, calling for the elimination of FGM/C. More can be done to bring the lack of support for FGM/C into the public sphere. Programme activities can stimulate discussion within practising groups so that individual views opposing the practice can be aired. Local and national media as well as other trusted communication channels can serve as a forum to disseminate information on decreasing support for FGM/C as well as to discuss the advantages of ending the practice. In West Africa, for example, traditional communicators, or griots, are passing along such information and stimulating debate about the practice through theatre and songs.

Collective pronouncements or declarations against FGM/C are effective ways to make evident the erosion in social support for the practice. They also send the message that non-conformance will no longer elicit negative social consequences. The efficacy of such an approach has been demonstrated in all 15 countries that are part of the Joint UNFPA-UNICEF Programme on FGM/C and in other countries, such as Niger. One result of the pronouncements is that families experience less social pressure to perform FGM/C and have less fear of social exclusion for not cutting their daughters. Over time, as more and more families are able to act in a way that is consistent with their personal preferences to end FGM/C, actual cutting will decrease. And, as individuals witness this transformation, they will have even greater assurance that the practice is no longer necessary for social acceptance.

This type of chain reaction may explain the process under way in many countries and in population groups within countries. In Burkina Faso, for example, support for FGM/C has been very low for decades, likely as a result of nationwide activities raising awareness of the harms of the practice as well as legislation prohibiting FGM/C, which has been enforced. Over this period, prevalence fell moderately but consistently. In the last 15 years or so, programme activities also provided opportunities for groups to collectively take a stand against the practice. The data indicate that the decline in prevalence during this period has accelerated.

Increase engagement by boys and men in ending FGM/C and empower girls

Discussion about FGM/C needs to take place at all levels of society, starting with the family, and include boys and men. This is especially important since the data indicate that girls and women tend to consistently underestimate the share of boys and men who want FGM/C to end.

Data also reveal that a large proportion of wives do not even know their husbands’ opinions of the practice. Facilitating discussion of the issue within couples and in forums that engage girls and boys and women and men may accelerate the process of abandonment by bringing to light lower levels of support than commonly believed, especially among men, who are likely to wield greater power in the community. In addition, the pattern indicating that girls and younger women tend to have less interest than their older counterparts in continuing the practice suggests that they can be important catalysts of change, including through intergenerational dialogues.

Women hold up signs during a ceremony renouncing FGM/C in the village of Cambadju in Bafatá region, Guinea-Bissau. The village is the first in the country to renounce the practice. The event, organized with support from the international NGO Tostan, a UNICEF partner, was attended by girls and young women, former traditional cutters, delegates from youth and women’s groups, government officials and others.

Increase exposure to groups that do not practise FGM/C

Where prevalence and support for FGM/C are very high, increasing exposure to groups that do not practise it and awareness of the resulting benefits is crucial. Through such exposure, individuals are able to witness that girls who are not cut thrive and their families suffer no negative consequences. This can make the alternative of not cutting plausible. The more affinity practising groups have with the non-practising groups they are exposed to and interact with, the greater the likelihood that positive influence will be exerted.

The data show that FGM/C prevalence, as well as support for the practice, is generally lower among urban residents, educated individuals and those from wealthier households, indicating that exposure is important. Urban areas tend to have more heterogeneous populations than rural areas, and members of groups that practise FGM/C are likely to interact more regularly with individuals and groups that do not. Similarly, wealthier individuals and families tend to have more opportunities to learn about or engage with non-practising communities.

Data also show that prevalence levels are typically lower among individuals that have completed higher levels of education. This suggests that education is an important mechanism to increase awareness of the dangers of FGM/C and knowledge of groups that do not practise it. Education also fosters questioning and discussion, and provides opportunities for individuals to take on social roles that are not dependent on the practice of FGM/C for acceptance.

Promote abandonment of FGM/C along with improved status and opportunities for girls, rather than advocating for milder forms of the practice

An important question for programming is whether advocating a shift to less severe forms of cutting is a path that is effective for eliminating FGM/C. The data on changes in the practice indicate a trend towards less severe forms of cutting in certain countries. However, overall, the type of cutting performed has changed little across generations. While the findings are not conclusive, the stability of the practice suggests that pursuing the elimination of FGM/C by moving towards a progressive reduction in the degree of cutting does not hold much promise. Moreover, the benefits of a marginal decrease in harm resulting from less severe forms of FGM/C need to be weighed against the opportunity cost of promoting the end of FGM/C as one of many harmful practices that jeopardize the well-being of girls and infringe upon their human rights. In countries including Ethiopia, Guinea-Bissau and the United Republic of Tanzania, programmes that aim to raise the status of girls and women in society are helping to discourage FGM/C as well as child marriage and forced marriage.

Next steps

Overall, the findings presented here confirm progress reported by programmatic initiatives aimed at ending FGM/C. They also contain some welcome surprises, such as a greater than expected decline in prevalence in the Central African Republic, which had not been previously documented. The report also raises new questions. For example, it is unclear why a discernible decline in FGM/C has not been found in Senegal, where concerted efforts to eliminate the practice have been under way for over a decade. Additional research and analyses are needed to provide a clearer picture of the reasons why data reflect greater or smaller than expected changes in the practice.

Measuring various aspects of FGM/C will need to continue, as it has for the last 20 years, in both high and low prevalence countries, along with stepped up efforts to encourage its full and irreversible elimination. As new rounds of household surveys are undertaken in the next few years, the outcome of these efforts will be more fully revealed. If commitment is sustained and programmes strengthened in light of increasing evidence, the data should show that the transformation currently under way has gained momentum, and that millions of girls have been spared the fate of their mothers and grandmothers.