Abstract

Abstract

Universal access to sexual and reproductive health services is one of the goals of the International Conference on Population and Development of 1994. The Millennium Development Goals were intended above all to end poverty. Universal access to health and health services are among the goals being considered for the post-2015 agenda, replacing or augmenting the MDGs. Yet we are not only far from reaching any of these goals but also appear to have lost our way somewhere along the line. Poverty and lack of food security have, through their multiple linkages to health and access to health care, deterred progress towards universal access to health services, including for sexual and reproductive health needs. A more insidious influence is neoliberal globalisation. This paper describes neoliberal globalisation and the economic policies it has engendered, the ways in which it influences poverty and food security, and the often unequal impact it has had on women as compared to men. It explores the effects of neoliberal economic policies on health, health systems, and universal access to health care services, and the implications for access to sexual and reproductive health. To be an advocate for universal access to health and health care is to become an advocate against neoliberal globalisation.

Résumé

L’accès universel aux services de santé sexuelle et génésique est l’un des objectifs de la Conférence internationale sur la population et le développement de 1994. Les objectifs du Millénaire pour le développement souhaitaient surtout éliminer la pauvreté. L’accès universel à la santé et aux soins de santé sont parmi les objectifs envisagés pour le programme de l’après-2015, qui remplacera ou élargira les OMD. Pourtant, non seulement nous sommes loin d’atteindre n’importe lequel de ces objectifs, mais nous semblons aussi nous être égarés en chemin à un moment donné. La pauvreté et le manque de sécurité alimentaire ont, par leurs multiples liens avec la santé et l’accès aux soins, freiné les progrès vers l’accès universel aux soins de santé, y compris pour les besoins de santé sexuelle et génésique. Une influence plus insidieuse est la mondialisation néolibérale. Cet article décrit la mondialisation néolibérale et les politiques économiques qu’elle a engendrées, son influence sur la pauvreté et la sécurité alimentaire et l’impact souvent inégal qu’elle exerce sur les femmes, par comparaison aux hommes. Il étudie les conséquences des politiques économiques néolibérales sur la santé, les systèmes de santé et l’accès universel aux services de soins, ainsi que les répercussions sur l’accès à la santé sexuelle et génésique. Défendre l’accès universel à la santé et aux soins de santé exige de lutter contre la mondialisation néolibérale.

Resumen

El acceso universal a los servicios de salud sexual y reproductiva es uno de los objetivos de la Conferencia Internacional sobre la Población y el Desarrollo de 1994. La finalidad primordial de los Objetivos de Desarrollo del Milenio era eliminar la pobreza. El acceso universal a la salud y los servicios de salud figuran entre los objetivos bajo consideración para la agenda post 2015, que sustituye o incrementa los ODM. Sin embargo, no solo nos falta mucho por lograr estos objetivos, sino que al parecer nos perdimos en el proceso Mediante sus múltiples vínculos con la salud y el acceso a los servicios de salud, la pobreza y la falta de seguridad alimentaria han impedido los avances hacia el acceso universal a los servicios de salud, incluidos los servicios de salud sexual y reproductiva. Una influencia más insidiosa es la globalización neoliberal. En este artículo se describe la globalización neoliberal y las políticas económicas que ésta ha engendrado, las maneras en que influye en la pobreza y en la seguridad alimentaria, y el impacto generalmente desigual que ha tenido en las mujeres en comparación con los hombres. Se exploran los efectos de las políticas económicas neoliberales en salud, sistemas de salud y acceso universal a los servicios de salud, así como las implicaciones para el acceso a la salud sexual y reproductiva. Abogar por el acceso universal a la salud y los servicios de salud equivale a abogar en contra de la globalización neoliberal.

Universal access to sexual and reproductive health care services has been defined as:

“The equal ability of all persons according to their need to receive appropriate information, screening, treatment and care in a timely manner, across the reproductive life course, that will ensure their capacity, regardless of age, sex, social class, place of living or ethnicity, to:

| • | decide freely whether and when to have children and how many children to have and to delay and prevent pregnancy, | ||||

| • | conceive, deliver safely, and raise healthy children and manage problems of infertility, | ||||

| • | prevent, treat and manage major reproductive tract infections and sexually transmitted infections including HIV/AIDS, and other reproductive tract morbidities such as cancer, and | ||||

| • | enjoy a healthy, safe and satisfying sexual relationship which contributes to the enhancement of life and personal relations.”Citation1 | ||||

A 2012 assessment of progress towards universal access to sexual and reproductive health services in 21 countries in Asia and the PacificFootnote* highlighted the considerable gap between the present situation and the desired goal. For example, more than a fifth of all women of reproductive age had an unmet need for contraception in the vast majority of countries examined. In eight countries, more than 50% of women delivered with no skilled help. Access to safe abortion services was poor, and unsafe abortions accounted for 10–16% of all maternal deaths. Barring a few exceptions, coverage of antiretroviral (ARV) therapy was below 50% of all people living with HIV, while ARV coverage of pregnant women living with HIV was lower than 25% in all but four countries. Sexuality education in secondary school curricula focused more on knowledge and less on life skills. Contraceptive prevalence rates among adolescents were low, suggesting that sexually active adolescents may not have the means to control their fertility. While between a quarter and half of adolescent girls had knowledge of HIV testing, less than 5% of adolescent girls actually got tested.Citation2

In an earlier paper I have argued that to achieve universal access to sexual and reproductive health services in Asia and the Pacific, we need to address the underlying social determinants of health and access to health services, including poverty, hunger and recurring economic and food crises which are linked to each other through multiple pathways.Citation3 In the present paper, I examine a more insidious link that connects all three (poverty, food security and universal access to health care): the forces of neoliberal globalisation.

The central thesis of this paper, which draws on examples from the Asia-Pacific region, is that the forces of neoliberal globalisation are at the root not only of recurring economic and food crises, but are also the most significant barriers to universal access to sexual and reproductive health services — both directly and through their impact on poverty and food security. The paper defines and describes neoliberal globalisation and the ways in which it influences poverty and food security, and often impacts unequally on women as compared to men. It explores the effects of neoliberal economic policies on health and universal access to healthcare services, the gendered nature of these effects, and the implications for universal access to sexual and reproductive health care services. And it proposes an agenda for action across movements for food security, health care and an end to poverty to confront neoliberal globalisation.

Neoliberal globalisation, poverty reduction and food security

Neoliberalism of the late 20th century may be understood as the “globalisation” of the ideology of economic liberalism, according to which “free” markets and “free” trade, unfettered by state regulations of any kind, nurture creativity and entrepreneurship and lead to economic growth and social well-being.Citation4

The “Washington Consensus” of 1989 laid the groundwork for neoliberal globalisation.Citation5 The term refers to a set of structural adjustment policies which low-income countries were required to adopt if they were to receive new loans from the World Bank and IMF loans to make debt repayments. These policies demanded major cuts in public expenditure, liberalisation of trade e.g. removal of tariffs and quantitative restrictions on imports and privatisation of state-run enterprises. The establishment in 1995 of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) and its many treaties further facilitated the adoption of neoliberal economic policies by many countries. These included, for example:

| • | the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS), requiring “open border” policies to allow the free entry and exit of capital from countries, and private investment from abroad in the services sector, including in health and education; | ||||

| • | the Agreement on Trade-related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) meant to protect patent rights held mainly by transnational corporations; and | ||||

| • | the Agreement on Agriculture, which enforces “free” trade in agricultural products. | ||||

International Financial Institutions “encouraged” low-income countries into “full participation” in WTO-ruled trade agreements.Citation5

Neoliberal economic policies and poverty

Neoliberal economic policies run contrary to measures essential for substantial and sustained poverty reduction. Many of the policy pathways underlined in the “Washington Consensus” have contributed to dampening poverty reduction in the Asia-Pacific region.

For example, “fiscal discipline” is an essential feature of neoliberal economic policies. This implies reducing the fiscal deficit in the government budget as far as possible, and hence cuts in public investments. Governments are, as a consequence, unable to invest adequately in public infrastructure and public services such as education and health — or invest adequately in poverty alleviation measures.Citation6 At the same time, trade liberalisation brought about the removal of tariffs, duties and taxes related to trade, further reducing public revenue.

Financial liberalisation makes countries vulnerable to crises resulting from speculative dealings in capital and capital flights out of the country. The Asian economic crisis of the late 1990s was a direct consequence of financial speculation, and caused a major setback in terms of poverty reduction in the region. During the first decade of the new millennium, new financial instruments were created to attract finance capital in search of higher and higher returns. The speculative adventurism of finance capital culminated in the devastating global economic crisis of 2008. According to Warren Buffett, innovative financial instruments such as derivatives were “lethal financial weapons of mass destruction and time bombs susceptible to explode and cause the implosion of the entire economic system”. Citation7

In addition to its contribution to economic destabilisation, financial liberalisation has in many countries also resulted in a shrinking of financial services available to small-scale producers and low-income groups. Having to compete with private international and national banks, public sector banks have had to pull back from providing subsidised credit to small-scale producers and subsistence loans to low-income groups. Economic crises also tend to affect employment and the wages of those working in the export-manufacturing and services sectors. Many more whose livelihoods depend on servicing the export sector and its workers also lost their jobs. For example, in Cambodia, where 70% of the exports consisted of garments, 18% of the total work force in the sector was laid-off during 2008 September — 2009 April. Those in casual employment found fewer days of work, for example, in Viet Nam workers reported a 30–50% decline in wage earnings between 2008 and early 2009.Citation8

The neoliberal path to economic growth in many Asia-Pacific countries was accompanied by increasing income inequalities. For example, between 1993 and 2004–05, the Gini co-efficient of income inequality increased from 0.41 to 0.47 in China, 0.33 to 0.37 in India, and 0.34 to 0.40 in Indonesia.Citation9 One important reason for this was that for every 1% of GDP growth, employment grew only by 0.4%.Citation8 Much of the growth was in sectors that were not labour intensive (e.g. information technology) and competition drove many labour-intensive sectors to adopt labour-displacing technologies. A large proportion of young people newly entering the labour force were left without suitable employment opportunities. Wages, especially in the informal sector of the economy, remained suppressed because of the large pool of unemployed people. The economic boom made only a limited contribution to human development, and while increasing average income levels, contributed to severe deprivation of the less-resourced sections of the population.Citation9

While the proportion of poor almost halved in the Asia-Pacific region between 1990 and 2011, progress in the reduction of income poverty was severely hampered by recurring crises on multiple fronts.Citation10 About 1.1 billion people in the region– 200 million more than those affected by income poverty– suffered multiple deprivations as measured by the Multi-Dimensional Poverty Index (MPI).Citation11 Footnote* Also, increasing inequality affected poverty reduction. If inequality had stayed stable instead of rising during 1990s and 2000s, around 240 million more people in Asia could have escaped poverty.Citation12

Neoliberal globalisation and food insecurity

According to the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), “food security exists when all people at all times have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life”.Citation13 Footnote† Neoliberal economic policies have contributed to food insecurity through increasing costs of cultivation, slow growth in agricultural production, speculation in agricultural futures commodities and the diversion of agricultural products and cultivable land to the production of biofuels. The result has been pauperisation of the small peasantry and food crises marked by increasing and volatile food prices.

Cuts in public investment have resulted in low investment in agricultural infrastructure, cuts in government subsidies for inputs and low-cost credit, resulting in high costs of production. Also, oil price increases have made petroleum-based fertilisers very expensive.Citation14

The WTO Agreement on Agriculture (AoA) has had an important role in making agriculture unviable for small and even medium-size farmers. High-income countries of the global North have been dumping their highly subsidised agricultural products in countries of the global South, destroying the opportunities for sales by small farmers.Citation15 Farmers forced to compete in the global market have tended to switch to cash crops, especially if they have had the resources to do so. For small farmers, however, agricultural production has become unviable and led to their exit from the agricultural sector. These have contributed to low overall increases in food production.Citation14

The global economic crises and the “open border” economic policies have contributed also to large-scale land acquisitions in countries of the South by investors in the North. For example, the financial crises have driven investment banks, pension funds and other investors to choose to invest in more stable assets such as land rather than volatile and unstable financial securities. Small and medium-size farmers in countries of the South are being displaced as a result of large-scale land acquisition, with consequences for their own and their countries’ food security.Citation16

Neoliberal economic policies have treated nature as a never-ending resource involving zero cost, and exploited natural resources beyond sustainability. The resulting climate change, with unpredictable and erratic climate, has made the lives of farmers even more insecure than they already were, with droughts and floods devastating agricultural production at regular intervals.

In addition to these processes of steady erosion in the food security of developing countries, neoliberal globalisation contributed directly to the food crisis of 2007 and the subsequent worsening of food insecurity through two major pathways: financial speculation in the food commodity market and the diversion of agricultural produce and land towards bio-fuel production.Citation8

In the 1980s, there emerged a market for commodities “futures” for food items. Futures markets are based on contracts between two parties to buy or sell a specified quantity of a commodity at a future date at a price agreed today. This was meant to protect producers and traders of commodities from sudden changes in market prices. De-regulation in the USA in 2000 permitted speculators with finance capital to enter and play the commodities futures markets and to make huge profits from short-term price rises. This resulted in extreme volatility in the prices of food grains that had nothing to do with supply and demand factors.Citation14 Between January 2007 and June 2008, the international food price indexFootnote§ rose by 54%. Real prices of rice tripled, wheat and maize more than doubled. There were again sharp rises in prices in 2010 which exceeded the 2008 peak prices.Citation17

Use of food crops for the production of bio-fuels has been another major factor. Several studies have arrived at the unambiguous conclusion that the demand for bio-fuel production drove soaring food prices. According to one estimate, increased demand for bio-fuel accounted for 30% of increases in real cereal prices, 39% of increase in real maize prices, 22% of increase in real wheat prices and 21% of the increase in real rice prices for the period 2000–07.Citation18

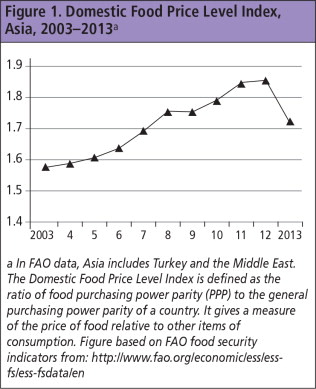

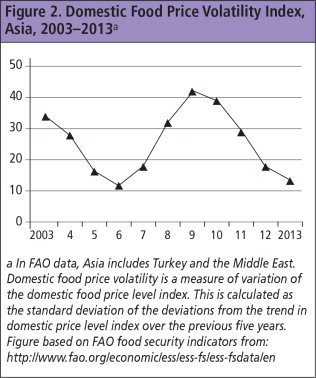

Food prices in Asia, which had remained relatively stable in the late 1990s and early 2000s, skyrocketed as a result of the global food crisis of 2007–08 and continued to increase until 2012. Fluctuations in prices within each year were also volatile (see and Footnote2).Citation19

Figure 2 Domestic Food Price Volatility Indexa a In FAO data, Asia includes Turkey and the Middle East. Domestic food price volatility is a measure of variation of the domestic food price level index. This is calculated as the standard deviation of the deviations from the trend in domestic price level index over the previous five years. Figure based on FAO food security indicators from: http://www.fao.org/economic/ess/ess-fs/ess-fsdata/en.

Figure 1 Domestic Food Price Level Indexa a In FAO data, Asia includes Turkey and the Middle East. The Domestic Food Price Level Index is defined as the ratio of food purchasing power parity (PPP) to the general purchasing power parity of a country. It gives a measure of the price of food relative to other items of consumption. Figure based on FAO food security indicators from: http://www.fao.org/economic/ess/ess-fs/ess-fsdata/en.

The food crisis of 2007 and the high prices that ensued resulted in an increase in the proportion of people living in poverty in Asia. According to a study covering 25 countries in Asia with a population of 3.3 billion people, a 10% increase in domestic food prices which occurred in the region during early 2011 would have created 64.4 million additional poor people (living on under PPP$1.25 per day) in these countries.Citation20

“Gendered” implications of neoliberal economic policies

Neoliberal economic policies have tended to impact differentially on women and men across social and economic strata, often to the disadvantage of women. Loss of employment is a major way in which women’s potential for economic empowerment may be adversely affected. For example, restrictive policies to contain inflation at very low levels could adversely affect employment. Experience in many low- and middle-income countries shows that when employment contracts, the proportion of women losing employment is higher than that of men; but they do not gain employment faster than men when employment expands. When the public sector is down-sized and privatised, more women are affected because a large share of women’s formal employment tends to be in the public sector.Citation21

Trade liberalisation has created new employment opportunities for women in export-oriented sectors.Citation21 In Southeast Asia, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, there were two to five female workers for every male worker in textiles, garments and electronic sectors.Citation22 However, because of intense international competition and the need to keep production costs low, there is limited scope for increases in wages and improvements in working conditions.Citation20 During times of crisis, women are the first to be laid off. For example, during the Asian economic crisis, seven times as many women in South Korea were laid off as men.Citation23

Cuts in public expenditure could mean a decline in public investment on basic needs and services, such as water supply and sanitation, public transport and childcare services. Because of the gender-based division of labour and women’s limited access to cash as compared to men, each of these would increase women’s workload related to household tasks. Studies from hill districts of Nepal, Pakistan, Viet Nam and China, carried out in the late 1990s, reported that women’s domestic tasks increased their workday by four to five hours as compared to men, especially in low-income households located in rural areas.Citation24

Yet another dimension of vulnerability that women face is the possibility of increased domestic violence in times of economic hardship. Studies from India observe that in times of economic crises, more women reported experiencing spousal violence, probably because men tend to vent their frustrations related to economic insecurity on their less powerful wives.Citation8

Gender roles cast women in an important role related to food security: as producers, procurers and processors of food, and as preparers of food, responsible for the nutritional security of members of their household. Often, this responsibility is carried out against serious odds. While the neglect of agriculture has affected the farming community overall, women farmers face additional difficulties because in most Asian countries (especially South Asia) few women possess land titles or legal ownership of the land on which they work. They therefore have less access to institutional credit, subsidised inputs and extension services and have to incur higher cultivation costs.Citation8

Food insecurity and crises take a higher toll on women than on men because of their role in procuring and preparing food. An in-depth study of the effect of food insecurity on rural women in Bangladesh and Ethiopia found that when there were spikes in food prices, women had to work 4.8 hours more every day in order to buy or prepare food at a lower price, or work more to earn more income.Citation25 As a consequence, in Bangladesh, 21% of the women had to take their children out of school to take care of the household tasks. Women often cut down on their own food intake to put more food on the table for their children and husbands. One woman from a Bangladesh village described her situation thus:

“I and my husband …have four children. My husband works on our 0.5 hectare land besides riding his rickshaw during monga (lean season). I also work as a daily labourer and earn only one dollar a day. I am not able to prepare good food to feed the whole family. I eat only once a day to give more food to my children and husband. I mainly eat fried wheat (sombaja) and puffed rice (muri) with chilli and salt.”Citation25

Neoliberal economic policies and universal access to health care services, including sexual and reproductive health services

Neoliberal globalisation has influenced health and healthcare by two different routes. One is through the effects of neoliberal economic policies on social and economic conditions, such as food crises, poverty and inequality. The second is through direct changes to healthcare systems, which I will argue are antithetical to achieving universal access to healthcare.

As described earlier, poverty reduction has been stalled while income inequalities have increased, and food prices have increased to hitherto unprecedented levels. Lives and livelihoods have become unpredictable, with repeated crises on multiple fronts. Together, these will have the effect of increasing the risk of physical and psychological distress and illness.

Periods of economic crisis cause major setbacks in health. A study using Demographic and Health Surveys conducted between 1984 and 2004 in 59 developing countries estimated that a 1% contraction in per capita GDP could result in an increase in the infant mortality rate of between 0.18 and 0.44 per 1000 births. This finding implies that between 1980 and 2004, a million additional infants died in countries that suffered severe economic setbacks.Citation26 Increases in food prices decrease the purchasing power of the population, with the poorest groups bearing a disproportionate share of the consequences. During 2006–08, increasing food prices decreased the purchasing power of the poorest households in the Asia-Pacific region by 24%, while the comparable figure for the richest households was only 5%.Citation8 Lower purchasing power would compromise a household’s ability to invest in essential resources for remaining healthy, e.g. preventive healthcare and nutritious foods such as milk and fruits. Finding the resources for universal health care would become unviable if economic policies cause more and more people to be ill or injured.

Structural Adjustment Policies ensuing from the Washington Consensus contributed to commercialisation of healthcare in a number of low- and middle- income countries (LMICs). “Health sector reform” policies advocated by the World Bank and other international players argued for a limited role for the state in the provision of healthcare and for an increased role for the private sector in the provision and financing of healthcare. Cuts in public expenditure in health and the introduction of cost-sharing measures and private insurance were all part of the Health sector reform package. Government was to provide only those healthcare services that had a “public good” characteristicFootnote* and others that may not otherwise be taken up if they came with a price tag, e.g. health education and immunisation. Thus, primary care was to be provided by the government while secondary and tertiary care was to be provided by the private sector, with market forces regulating the supply of and demand for these services.Citation27

Hsiao (1994) has provided a comprehensive critique of the “marketisation” of healthcare, i.e. the use of market forces to finance and provide health services as the most “efficient” use of resources.Citation28 The “market”’ or “free and competitive” markets work on the premise that both buyers and sellers are on the same level ground and are equal. Each party pursues its self-interest and this creates competition. Sellers try to operate efficiently in order to minimise their costs and maximise their profits, while buyers try to maximise their utility and minimise their prices. The market for health care services, unfortunately, does not have any of these features. Patients do not possess the technical knowledge or the information necessary to make decisions and have to depend on providers for guidance. Patients are not in a position to shop around for the best option, especially in a health emergency, and also if they have only one or two providers to choose from. The market system gives the more powerful stakeholders – providers in this case – the freedom to use this power to maximise their profits through inducing demand for health care services (rational or irrational, as long as it is not unsafe), fixing higher prices for services, and selecting and privately insuring patients who pose the least risk.Citation28

Marketisation of healthcare thus escalates cost of health care services within a country. As health care service costs escalate, the proportion of people who incur catastrophic health expenditure, and the proportion pushed into poverty as a consequence, also increase. Worse still, those who cannot pay for health care services at the point of service delivery have to delay health-care seeking and may reach a health facility when it is too late to help or save them.Citation29

At the same time, marketisation would also contribute to the deterioration of the public sector in health through multiple pathways. One would be through the internal brain drain of health providers from the public to the private sector, leaving many health facilities with vacant positions and under-qualified staff. Secondly, public investments would decline as the state is no longer obliged to provide anything but the most basic services. Those without the ability to pay for private health services have only two options – to seek public sector health care services of inadequate quality, or not seek health care services at all. This clearly is not the path to universal access to health care.Citation29

Within this context, private for-profit insurance, also one ingredient of marketisation of health care services, adds further complexities. Only the better-off are able to afford private for-profit insurance. Also, a two-tier system of health care services is created in which those who are insured are assured of health care services while the others do not count. The World Health Report 2010 asserts that, “it is impossible to achieve universal coverage through insurance schemes when enrolment is voluntary” (as in the case of private for-profit insurance). This is because compulsory pre-payment by those who can afford to contribute is needed to cross-subsidise funding for health care for those who cannot afford to pay. Where most of the well-to-do buy private for-profit health insurance, the government has no access to this stable pool of money, which may be needed in addition to revenue from taxes, to cross-subsidise health services.Citation29

Neoliberal globalisation has also set in motion a number of global forces that impact on health care services within countries. The first is the emergence of Global Health Initiatives (GHIs) in the late 1990s and early 2000s. These partnerships involve several types of entities – multilateral and bilateral agencies, international NGOs, for-profit organisations, usually manufacturers of pharmaceutical goods and medical equipment and supplies. At the end of the first decade of the Millennium, the large GHIs had emerged as leaders in development assistance for health, and had become agenda setters for global health policy, while the World Health Organization and the World Bank became relatively minor players. By 2009, more than 100 GHIs existed, addressing 27 health concerns. Four GHIs are considered as being by far the most influential in global health. These are the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (Global Fund); Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation (GAVI); US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR); and World Bank Multi-Country AIDS Programme (MAP).Citation30

GHIs have moved the clock back by channelling most of the available global resources for health into vertical interventions, paying scant attention to social determinants of health or to redressing inequities in health. Further, the influx of disease-specific funding into national health systems often distorts health service delivery and the health workforce away from other equally, if not more, important health concerns. For example, whereas access to HIV services increased from 5% to 31% over the four years 2003–2007, the proportion of births attended by skilled birth attendants showed a very small increase – from 61% to 65% in the 16 years 1990–2006.Citation25,31 The presence of highly paid positions in non-state sector projects funded by GHIs has contributed to an already high level of attrition of the health workforces through international migration.Citation30

Recent articles have observed that Global Health Initiatives have shifted the focus at global level away from comprehensive SRH services towards infectious diseases, with particular emphasis on treatment rather than prevention, increasing demand and stimulating new markets for medicines, and bypassing existing public health services to provide such services through vertical programmesFootnote* – all of which have negative equity effects. They have contributed to the fragmentation of ICPD’s comprehensive sexual and reproductive health agenda into narrow silos of maternal health and HIV, while “other sexual and reproductive health” needs receive more lip service than investment or political commitment.Citation30

The second force is constituted of World Trade Organization treaties and agreements that have a direct bearing on health care services. For example, the Trade-related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) agreement of 2004 was based on the premise that protecting intellectual property rights was essential for promoting innovation in the pharmaceutical and medical products sector. TRIPS has had the effect of driving up prices for most medicines, thus escalating costs of healthcare for both individuals and countries. The only exceptions are HIV and AIDS drugs, which have been made available through compulsory licensingFootnote† in several countries.Citation14

The General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) of 1995, also a WTO treaty, has opened up borders to trade in health services. Foreign direct investment (FDI) in healthcare tends to accelerate marketisation of healthcare, and may be detrimental to universal access to healthcare.Citation32

Marketisation of healthcare is likely to impact more negatively on women than men. Women are reported to incur, on average, higher out-of-pocket expenditure for health care than men. This is probably due to their reproductive health needs as well as the greater burden of chronic diseases. Using maternity and abortion services and services for reproductive tract infections can cost close to a household’s average monthly income and could be several times more than the monthly household income of those living below the poverty line. Vulnerable groups without access to financial resources, e.g. adolescents, the elderly and those not engaged in the formal economy, have greater sensitivity to price changes. When charges for services and/or medicines are introduced or increased, those with limited ability to pay are discouraged from using health services – both preventive and curative.Citation33

The introduction and promotion of private health insurance as a health-financing mechanism again places the most vulnerable, particularly women, at a disadvantage. Since many women are not employed in the formal sector of the economy, their ability to pay regular premiums may be limited. In the resource-rich countries, where such policies emanate from, the United States provides a salutary example of how private health insurance can exclude payment for essential sexual and reproductive health services. A 2008 report from the United States, based on an analysis of 3,500 individual insurance plans, found that many of them practised “gender rating” and charged women higher premiums than men of the same age because of their greater use of health services. Insurance companies were also able to reject applications for reasons specific to women, for example, women survivors of domestic violence and women with a previous caesarean.Citation34 Routine reproductive health services, including contraception, abortion and delivery,were considered “non-insurable” as stand-alone benefits because they are high-probability and non-random events. Individual private insurance plans in the United States therefore do not usually cover maternity services. Those who wish to be covered have to pay an additional premium, yet this gives coverage for only a limited number of maternity-related services. Many plans cover only a few contraceptive methods for women, and so on.Citation34

A 2005 synthesis of available evidence from Asia, Africa and Latin America on how neoliberal health sector reform policies have affected reproductive health services found that health sector reform ran counter to and undermined the universality and integrality of the ICPD goals by exacerbating inequalities in health. Unregulated public–private interactions have skewed services towards urban areas, and existing services were generally only accessible to those who could pay. Publicly-funded and/or -provided SRH services remained basic and limited.Citation27 A more recent analysis of 45 clinical social franchise networks of for-profit private health practitioners for the provision of reproductive health services suggests that not much may have changed since 2005 in terms of the contribution of privatisation to worsening inequalities in access to comprehensive reproductive health services.Citation35

Twenty years after ICPD, we seem not only to be far away from achieving its goals but also appear to have lost our way somewhere along the line. Continuing along the same path will not take us to our destination. It is time to step back and re-chart our future trajectory.

Towards a brave new world of prosperity, equity and well-being: a call for action

It is time to forge a new agenda for action. Movements for SRHR, poverty eradication, food sovereignty and human rights need to forge alliances to stop the forces of neoliberal globalisation from devastating the world.

A combined movement against neoliberal globalisation would call for fundamental changes in the rules of the game in the global economy, especially the rules set by the World Trade Organization, International Monetary Fund, World Bank and global corporations. The time has come to publicly defy these forces and to advocate for an alternative path to development that would guarantee a life of dignity, equality and well-being to everyone.

We do not have to look far for solutions. Clear guidelines have been outlined by many scholars and activists on the path that we need to traverse. In this section, I draw extensively on such sources to suggest how to achieve a sustainable economy where access to the resources necessary for a healthy life would be enjoyed by all. I start with changes needed in global economic policies and then present an agenda for change within the health sector to make universal access to healthcare a reality.

Changes in national and global economies

The fundamental premise on which changes in the national and global economy would be based is that economic growth does not amount to development unless the proceeds of such growth are invested in poverty reduction and ultimately, the eradication of absolute poverty. As enunciated in a UN Development Programme (UNDP) report, this would mean directing resources “to the sectors in which the poor work (agriculture), areas in which they live (relatively backward regions), factors of production which they possess (unskilled labour) and outputs which they consume (food)”. (p.74)Citation8

| • | Public investment directed towards the poor, and not high growth rates, is a necessary condition for poverty reduction | ||||

The UNDP report asserts that governments are able to make public investments and bring about poverty reduction even when their economies have a relatively low rate of growth. For example, in Sri Lanka and Malaysia in the 1980s, annual poverty reductions of between 4–7% were achieved at a time when average annual growth in per capita incomes was only about 3%, by investing heavily in sectors that would benefit the poor.Citation8 Conversely, cutting public investment with a view to restraining fiscal deficit hurts poverty reduction and stops improvements in living standards of most of the population.

The concern with fiscal deficit is motivated by the neoliberal diktat to contain inflation at 3–5%. This is not based on any empirical evidence that higher than 5% or even 10% inflation can hurt economic growth. Several countries have experienced high growth rates alongside high rates of inflation. For example, China grew at almost 9% during 1990–2001 when its average rate of inflation was 8%, and Indonesia’s real GDP grew at the rate of 7.7% during the 1970s when its inflation rate was as high as 17%. This is not to say that inflationary pressures that have a destabilising effect on the economy need not be contained. The take-home lesson is that undue concern about inflation should not deter countries from making necessary public investments on poverty reduction and augmenting productive capacity.Citation6

How would one generate the revenue needed for public investment? Income and wealth taxes, urban land taxes and trade-related taxes are sources that need to be tapped better and could raise a significant amount of funds for public investment. It does not seem to be true that unless income and wealth taxes are maintained at low levels there will be no motivation for increasing incomes. In high-income countries, the ratio of income to consumption taxes is more than double, whereas the converse is true for LMICs.Citation36

| • | Cancel external debts of LMICs | ||||

Even if enough public revenue is raised by an economy, its ability to invest this for the welfare of its people may be seriously compromised by the burden of debt-servicing. According to a 2005 estimate, debt-servicing liabilities far exceeded overseas development aid received by many LMICs. For the poorest countries (approximately 60 of them), US $550 billion has been paid in both principal and interest over the last three decades, on US$540billion of loans, and yet there is still a US$523 billion dollar debt burden.Citation37 There could never be a level playing ground for economic interaction between countries unless the many promises of debt write-offs are honoured.

| • | Legitimise and enable government regulation of the international flow of finance and international trade | ||||

There is more than sufficient evidence of the detrimental consequences of financial liberalisation for countries’ well-being. Neoliberal policies have destabilised economies, made prices volatile and impoverished millions. There is no reason why countries should not insist on regulating the movement of finance capital to minimise its negative effects and maximise the benefits for their population. Viet Nam and China have introduced controls to protect themselves against the volatility of external capital flows,Citation6 for example.

Countries also need to adopt a trade strategy that benefits the creation of stable employment for the poorest, for young people and for women, and not adopt policies to attract foreign direct investment at the cost of disempowering its labour force and maintaining low wage rates. “Foot-loose” capital (unregulated and free to move from country to country) should not be permitted entry and exit as it pleases. What this implies is a more equal relationship between countries engaging in trade. High income countries must not to be permitted to export their subsidised food to LMICs unless they open their doors for imports from LMICs.

Changes in systems of food production and agricultural polices

An agenda for change in systems of food production and agricultural policies was presented at the World Food Summit of 1996 by La Via Campesina, an international movement of peasants opposed to neoliberal globalisation’s impact on the world’s food system.Citation38 This agenda, summarised briefly below, goes beyond achieving food security. It calls for “food sovereignty”, which puts individuals who produce, process, distribute and consume food at the centre of decisions on food and agricultural policies.

| • | Provide constitutional guarantees for the right to food and pursue concomitant agricultural and food policies | ||||

One of the fundamental demands of La Via Campesina is that the right to food be upheld by governments. Policies that would contribute to promoting the right to food would include, for example, prioritising investment in the agricultural sector; sustainable management of natural resources in the process of food production to ensure sustained productivity; reorganisation of food trade to ensure availability of affordable food for domestic consumption.

| • | Privilege the right of producers, processors, distributors and consumers of food over all others | ||||

Giving ownership and control of land that they work on to landless and farming people and especially women is essential for achieving food sovereignty. Owner farmers with security of ownership would have a greater motivation to invest resources in farming. Small farmers, and especially women, will have an important say in policies that affect them. Governments will uphold communities’ right to seeds, productive resources, a safe environment and access to the commons.

Policies that hurt local small farmers will be consciously avoided by governments. Some examples include policies that encourage sale of cultivable land to speculative investors; cut public subsidies to small farmers; facilitate and privilege MNCs control over agricultural production; and food imports that could hurt the livelihood of local small farmers.

Health sector changes for universal access

Economic policies that favour substantial increases in public investment for ending poverty and improving the conditions of the poor would by definition encourage public investment in health.

| • | Regulate the private sector in health in consonance with national health goals | ||||

To move from increased public investment in health towards universal access will require firm action by governments to regulate the private sector in health in consonance with national health goals. Governments need to intervene in the “market” for health care services to offset the very unequal position of patients vis-à-vis health care providers through, for example, quality control measures to prevent provider-induced demand for unnecessary or irrational health care services.

Entry of international, private, for-profit players into the provision of health care services also needs to be regulated, with permission given to operate only if there is evidence that confirms they will contribute to narrowing inequities in access to health care services. In this context, it is time to examine the equity impact of the role played by Global Health Initiatives and of the role of multilateral and bilateral donors and international NGOs, in the promotion of the for-profit private sector in health in many LMICs.

| • | Implement tax-based public financing of health care services | ||||

Suitable pre-payment mechanisms are needed to ensure that ability to pay does not deter access at the time of illness. The general consensus in this regard is that tax-based public financing of health care services would be more likely to contribute to universal access than any other mechanisms for financing health services.Citation29,39 This is especially so if there is a progressive system of taxation of income and wealth and if these are the main contributors to tax revenue. Such a mechanism cross-subsidises the poor from contributions of the better-off in society and is redistributive and inclusive.

| • | Regulate the cost of medicines and medical products and make the proceeds of scientific research a global public good | ||||

Universal access to health care services will not be possible unless medicines and medical product costs are contained and the proceeds of scientific research become a global public good to benefit humankind. There is need to challenge patent protection for monopolistic control and maximising profits, and to challenge TRIPS in order to protect people’s, rather than corporate, interests.

Universal access to sexual and reproductive health needs to be seen within the context and the larger goal of universal access to health and health care services. Siloed approaches that narrowly focus on one specific area, whether tuberculosis or family planning or HIV and AIDS, may result in inefficient investment of resources, especially in weak health systems – and may even result in their further weakening – and not achieve the desired goals.

| • | Implement universal, not targeted, coverage | ||||

Within a tax-funded health care system, the aim should be universal rather than targeted coverage. Comprehensive sexual and reproductive health services should be a part of the “essential services” package. If the range of SRH services provided is narrow, then there will not be adequate financial protection from catastrophic health expenditure. Important areas for immediate action include substantial investment in increasing availability of services overall and prioritising closing the gap across rural and urban locations and inaccessible geographic regions of the country.

| • | Consult with communities | ||||

Consultation with communities about appropriate and acceptable health care services is essential to greater usage. In many instances negotiation and cooperation between state health service providers and community-based organisations can resolve the cultural and social barriers to access. For example, negotiation about acceptable methods of contraception can increase contraceptive use.

| • | Remove barriers to universal access to sexual and reproductive health services | ||||

Universal access to sexual and reproductive health requires two other formidable barriers to be removed. The first is legislative restrictions on safe abortion services and policies that restrict the access of adolescents and young people to information and services, such as sexuality education, contraceptive services, safe abortion services and STI treatment. The second is health system blindness to gender-power inequalities in society. Policies for financing and provision of health care services need to factor in women’s unequal access to resources for seeking health care and limited decision-making power.Citation3

Neoliberal globalisation and economic policies influenced by it underlie poverty, hunger, avoidable ill-health and lack of healthcare access, including poor access to sexual and reproductive health services. To be an advocate for universal access to sexual and reproductive health services is to advocate against neoliberal economic policies.

Acknowledgments

This paper is a shortened version of the monograph “What It Takes: Addressing Poverty and Achieving Food Sovereignty, Food Security, and Universal Access to Sexual and Reproductive Health Services.” Kuala Lumpur, Asian-Pacific Resource and Research Centre for Women (ARROW), 2014. Many thanks to ARROW, who also provided funding support for research to produce the monograph.

Notes

* Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Burma, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Kiribati, Lao PDR, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Viet Nam.

* The Multi-Dimensional Poverty Index (MPI) measures acute human poverty. People deprived in a third or more of the three dimensions of health, education and living conditions are said to be multi-dimensionally poor.

† According to this definition, nutritional security is an integral component of food security.

§ The FAO Food Price Index is a measure of the monthly change in international prices of a basket of food commodities. It consists of the average of five commodity group price indices (meat, dairy, cereals, vegetable oils and sugar), weighted with the average export shares of each of the groups for 2002–2004.

* A “public good” has two essential features: (1) Non-excludability: the benefits derived from the provision of pure public goods cannot be confined only to those who have actually paid for it. (2) Non-rival consumption: consumption of a public good by one person does not reduce the availability of a good to everyone else – therefore, we all consume the same amount of public goods even though our tastes and preferences for these goods (and therefore our valuation of the benefit we derive from them) might differ. Examples of public goods include flood control, health education, broadcasting services, public water supplies, street lighting, lighthouse protection for ships, etc.

* Vertical programmes are generally disease specific and promote targeted clinical interventions delivered by a specialized service with its own management structure. The “pulse polio” intervention is a vertical programme, and so are family planning programmes that are not part of a comprehensive sexual and reproductive health programme in many countries.

† The “compulsory licensing” provision of TRIPS permitted governments to enact domestic laws to manufacture a generic medicine even for those medicines that were under patent protection under certain conditions: if the cost of the patented product was too high, if it was unavailable, or if it was not being manufactured by the patent owner. However, the vast majority of lower-middle income countries are not able to use the compulsory licensing provision because they do not have in-country manufacturing capacity or have weak institutions which cannot enact and/or implement domestic laws. Citation13

References

- World Health Organization. National-level monitoring of the achievement of universal access to reproductive health: conceptual and practical considerations and related indicators. Report of a WHO/UNFPA consultation, 13–15 March 2007. 2007; WHO: Geneva.

- TKS Ravindran. Universal access to sexual and reproductive health in Asia and the Pacific: How do we get from here to there?. Arrows for Change. 18: 2012; 6–7.

- TKS Ravindran. Universal access to sexual and reproductive health: How far away are we from the goal post? In: Action for sexual and reproductive health and rights: Strategies for the Asia-Pacific Beyond ICPD and the MDGs. 2012; Asian-Pacific Resource and Research Centre for Women: Kuala Lumpur. www.arrow.org.my/uploads/Thematic_Papers_Beyond_ICPD_&_the_MDGs.pdf.

- Dag Einar T, Amund L.. What is neoliberalism? Oslo, Department of Political Science, University of Oslo. p.14–15. http://folk.uio.no/daget/What%20is%20Neo-Liberalism%20FINAL.pdf.

- Juego B, Schmidt JD. The political economy of the global crisis: neo-liberalism, financial crises, and emergent authoritarian liberalism in Asia. Paper presented at Fourth Asian Political and International Studies Association Congress on Asia in the Midst of Crises: Political, Economic, and Social Dimensions. 12–13 November 2009, Makati City, Philippines. http://vbn.aau.dk/files/19023517/Juego-Schmidt_APISA_4_Paper__Final_.pdf.

- T McKinley. Economic policies and poverty reduction in Asia and the Pacific. Alternatives to neoliberalism. 2004. New York, UNDP.

- W Buffet. Warren. Buffet on derivatives. Edited excerpts from the Berkshire Hathaway 2002 Annual Report. www.fintools.com/docs/Warren%20Buffet%20on%20Derivatives.pdf

- A Chhibber, J Ghosh, T Palanivel. The global financial crisis and the Asia-Pacific region: a synthesis study incorporating evidence from country case studies. 2009; UNDP Regional Centre for Asia and the Pacific: Colombo.

- Asian Development Bank. Key indicators for Asia and the Pacific. 2008; Asian Development Bank: Manila.

- UNESCAP. Poverty and inequality. In: Statistical Yearbook for Asia and the Pacific 2013. http://www.unescap.org/stat/data/syb2013/ESCAP-syb2013.pdf

- S Alkire, JM Roche, ME Santos. Multidimensional Poverty Index 2011. Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative. 2011; University of Oxford: Oxford. www.ophi.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/OPHI-MPI-Brief-2011.pdf.

- Asian Development Bank. ADB Fast Fact: How can Asia respond to global economic crisis and transformation?. 2012; Asian Development Bank: Manila. www.adb.org/features/fast-facts-global-economic-crisis-and-transformation.

- Food and Agricultural Organization. Rome Declaration on World Food Security and World Food Summit Plan of Action, 1996. http://www.fao.org/docrep/003/w3613e/w3613e00.htm

- People’s Health Movement. Medact, Health Action International, Medicos International and Third World Network. Global Health Watch 3: An Alternative World Health Report. 2013; Zed Publishers: London. www.ghwatch.org/sites/www.ghwatch.org/files/global%20health%20watch%203.pdf.

- C von Werlhof. The consequences of globalisation and neoliberal policies. What are the alternatives? Global Research. 1 February 2008. www.globalresearch.ca/the-consequences-of-globalization-and-neoliberal-policies-what-are-the-alternatives/7973

- R Adbib. Large scale foreign land acquisitions: neoliberal opportunities or neocolonial challenges? A multiple-case study on three sub-Saharan African countries: Ethiopia, Tanzania and Uganda. Master’s Thesis. 2012; School of Global Studies, Gothenburg University. https://gupea.ub.gu.se/bitstream/2077/29419/1/gupea_2077_29419_1.pdf.

- Asian Development Bank. Food security in Asia and the Pacific. 2013; Asian Development Bank: Manila.

- MW Rosegrant, T Zhu, S Msangi. The impact of biofuel production on world cereal prices. 2009. International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington DC, Unpublished paper as quoted in Chhibber et al, 2009 at [8].

- Food and Agricultural Organization. FAO food security indicators. http://www.fao.org/economic/ess/ess-fs/ess-fsdata/en

- Asian Development Bank. Global food price inflation and developing Asia. 2011; Asian Development Bank: Manila.

- S Razavi, C Arza, E Braunstein. Gendered impacts of globalisation: employment and social protection. Overview. 2012. Geneva, United Nations Research Institute for Social Development, http://bit.ly/1k9iZzq.

- Dejardin AK, Owens J. Asia in the global economic crisis: impacts and responses from a gender perspective. Paper presented at ILO Workshop on Responding to the Economic Crisis – Coherent Policies for Growth, Employment and Decent Work in Asia and Pacific, Manila, Philippines, 18–20 February 2009. www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/–-asia/–-ro-bangkok/documents/meetingdocument/wcms_101737.pdf.

- Seguino S. The global economic crisis, its gender implications and policy responses. Paper prepared at Gender Perspectives on the Financial Crisis Panel, Fifty-Third Session, Commission on the Status of Women, United Nations, 7 March 2009. www.uvm.edu/˜sseguino/pdf/global_crisis.pdf.

- R Balakrishnan. Rural women and food security in Asia and the Pacific. Prospects and paradoxes. 2005; Food and Agricultural Organisation, Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific: Bangkok, 37. www.fao.org/docrep/008/af348e/af348e00.htm.

- ZB Uraguchi. Food price hikes, food security, and gender equality: assessing the roles and vulnerability of women in households of Bangladesh and Ethiopia. Gender and Development. 18(3): 2010; 491–501. 10.1080/13552074.2010.521992.

- World Bank Development Research Group. Lessons from World Bank Research on Financial Crises. Policy Research Working Paper 4779. 2008; World Bank: Washington, DC.

- TKS Ravindran, H de Pinho. The Right Reforms? Health sector reforms and reproductive health. 2005; School of Public Health, University of Witwatersrand: Johannesburg.

- WC Hsiao. ‘Marketisation’ - the illusory magic pill. Health Economics. 3: 1994; 351–357.

- Oxfam. Universal health coverage. Why health insurance schemes are leaving the poor behind. Oxfam Briefing Paper. 2013; Oxfam: Oxford, 176. http://www.oxfam.org/sites/www.oxfam.org/files/bp176-universal-health-coverage-091013-en_.pdf p. 12.

- World Health Organization. Maximizing positive synergies collaborative group. An assessment of interactions between global health initiatives and country health systems. Lancet. 273: 2009; 2137–2169. www.who.int/healthsystems/publications/MPS_academic_case_studies_Book_01.pdf.

- World Bank. International Comparison Programme database. GNI, PPP (current international $). http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNP.MKTP.PP.CD/countries/1W?display=graph

- Juego B, Smith JD. The political economy of global crisis: neoliberalism, financial crises and emergent authoritarian liberalism in Asia. Paper presented at 4th Asian Political and International Studies Association Congress, Asia in the Midst of Crises: Political, Economic, and Social Dimensions. 12–13 November 2009. Makati City, Philippines.

- World Health Organization. Gender, women and primary health care renewal: a discussion paper. 2010; WHO: Geneva. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241564038_eng.pdf.

- L Codispotim, B Courtot, J Swedish. Nowhere to turn: how the individual health insurance market fails women. 2008; National Women’s Law Centre: Washington, DC. www.nwlc.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/NWLCReport-NowhereToTurn-81309w.pdf.

- TKS Ravindran, S Fonn. Are social franchises contributing to universal access to reproductive health services in low-income countries?. Reproductive Health Matters. 19(38): 2011; 85–101.

- V Tanzi, H Zee. Tax policy for developing countries. Economic Issues. 2001. 27(March).

- A Shah. Third world debt undermines development. 2007. www.globalissues.org/issue/28/third-world-debt-undermines-development

- Campesina Via. Food sovereignty: a future without hunger. The right to produce and access to land, 1996. http://www.voiceoftheturtle.org/library/1996%20Declaration%20of%20Food%20Sovereignty.pdf

- J Kutzin. Anything goes on the path to universal health coverage? No. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 90: 2012; 867–868.