Abstract

Abstract

China has launched the one-child policy to control its rapidly expanding population since 1979. Local governments, tasked with limiting regional birth rates, commonly imposed induced abortions. After 1994, China’s family planning policy was relatively loosened and mandatory induced abortion gradually gave way to client-centered and informed-choice contraceptive policy and the “Compensation” Fee policy. This study assesses trends in and determinants of induced abortion among married women aged 20–49 in China from 1979 to 2010, using data from national statistics and nationally representative sample surveys. The incidence of induced abortions among married women aged 20–49 began to decrease in the mid-1990s. The induced abortion rate reached its highest level in the early 1980s (56.07%) and its lowest level in the 2000s (18.04%), with an average annual rate of 28.95% among married women 20–49 years old. The likelihood of a pregnant woman undergoing an induced abortion during this period depended not only on individual characteristics (including ethnicity, age, education level, household registration, number of children, and sex of children), but also on the stringency of the family planning policy in place. The less stringent the family planning policy, the less likely married women were to undergo an induced abortion.

Résumé

La Chine a lancé la politique de l’enfant unique en 1979 pour maîtriser sa croissance démographique rapide. Les autorités locales chinoises, chargées de limiter les taux de natalité au niveau régional, ont fréquemment imposé des avortements. Après 1994, la politique de planification familiale a été relativement assouplie et les avortements obligatoires ont été remplacés par une politique contraceptive centrée sur les clients et le choix éclairé, ainsi que par la politique d’indemnisation sociale. Cette étude évalue les tendances de l’interruption de grossesse et ses déterminants chez les femmes mariées âgées de 20 à 49 ans en Chine de 1979 à 2010, à l’aide de statistiques nationales et d’enquêtes auprès d’échantillons représentatifs à l’échelon national. L’incidence des avortements chez les femmes mariées âgées de 20 à 49 ans a commencé à diminuer à la moitié des années 1990. Le taux d’avortement induit a atteint son plus haut niveau au début des années 1980 (56,07%) et son plus bas niveau dans les années 2000 (18,04%), avec un taux annuel moyen de 28,95% chez les femmes mariées âgées de 20 à 49 ans. La probabilité qu’une femme enceinte avorte pendant cette période dépendait non seulement de caractéristiques individuelles (notamment l’ethnicité, l’âge, le niveau d’instruction, l’enregistrement du ménage, le nombre et le sexe des enfants), mais aussi de la rigueur de la politique de planification familiale en place. Moins la politique de planification familiale était stricte, moins les femmes mariées risquaient d’avorter.

Resumen

En 1979 China lanzó la política de hijo único para controlar el rápido crecimiento de su población. Ante la tarea de limitar las tasas regionales de natalidad, los gobiernos locales de China comúnmente imponían abortos inducidos. Después de 1994, se relajó la política de planificación familiar de China y gradualmente ocurrió la transición de abortos inducidos obligatorios a una política de anticoncepción y elección informada centrada en los usuarios, así como la política de Compensación Social. Este estudio evalúa las tendencias y los determinantes relacionados con el aborto inducido entre mujeres casadas de 20 a 49 años de edad, desde 1979 hasta 2010, con datos de estadísticas nacionales y encuestas de muestras nacionalmente representativas. La incidencia de abortos inducidos entre mujeres casadas de 20 a 49 años de edad empezó a disminuir a mediados de la década de los noventa. La tasa de abortos inducidos alcanzó su mayor nivel a principios de los noventa (56.07%) y su menor nivel en la década de 2000 (18.04%), con una tasa anual promedio de 28.95% entre mujeres casadas de 20 a 49 años de edad. La probabilidad de que una mujer embarazada tuviera un aborto inducido durante este período dependía no solo de sus características personales (como etnia, edad, nivel de escolaridad, registro de su hogar, número y sexo de sus hijos), sino también del rigor de la política de planificación familiar vigente. Mientras menos estricta la política de planificación familiar, menos probable era que una mujer casada tuviera un aborto inducido.

Induced abortion is a common practice among women who seek to limit the number of children they have and to terminate unwanted pregnancies. Induced abortion was illegal at the foundation of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, due to the government’s desire for increased population. Women were encouraged to have more children, and most married couples did not plan births. Consequently, population increased at an accelerated rate.Citation1 However, women who still needed abortions began seeking abortions from unprofessional clinics. Unsafe abortions were on the rise.Citation2 In order to address the issue, the central government approved the Regulation of Contraception and Induced Abortion in August 1953 and began to promote contraception and supply contraceptives, and made abortion legal.Citation3

This Regulation was almost withdrawn during the Great Leap Forward and the national famine from 1959 to 1961. The famine triggered a population boom, and China entered its second peak period for childbearing.Citation2 From 1962 to 1972, the annual number of births in China averaged 26.69 million. The central government called for family planning and advocated the use of contraceptives. However, due to the lack of a deep understanding of the seriousness of the population problem, the government did not initially develop a clear population policy, and contraceptive provision was not carried out effectively.Citation4

It was not until 1973 that the government launched a nationwide family planning programme to cope with the increasing socioeconomic pressure posed by rapid population growth. This programme offered birth control methods and family planning services nationwide.Citation3,4 Contraceptive and abortion services were extended into the rural areas, and there was extensive promotion of later marriage, longer intervals between births, and smaller families (wan, xi, shao). Although this policy had some impact, it was officially regarded as incapable of limiting the population to 1.2 billion by 2000, which was the official target.

Under such circumstances, the one-child policy (one-size-fits-all, urban or rural), known as the world’s strictest family planning policy, was introduced in 1979. After that, a series of accompanying policies and actions related to the one-child policy were successfully instituted. The following year, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CPC) issued an open letter, calling for CPC and Communist Youth League members to have only one child in a bid to improve lives.Citation5 In essence, the “open letter” not only advocated the one-child policy, but was a mandatory order to implement a family planning programme alongside the planned economy. The State Family Planning Bureau drew up an official target of the maximum total fertility called for under the policy.Citation6 They set an average limit of 1.2 children per woman nationally in the early and mid-1980s. With this official introduction of the mandatory one-child policy, China entered an era of “slam on the brakes” population control. Citation2,7

Since then, the one-child policy has remained in force. Only the stringency of implementation has been modified, as this paper will discuss, during three distinct periods between 1979 and 2010: the tightened policy period, the moderate policy period, and the loosened policy period.Citation8 During the years 1979–1988 and the early 1990s, the one-child policy was tightened. Especially from 1980 to 1983, the one-child policy was enforced mainly through “shock drives” (tu ji), such as intensive mass education programmes and abortion–sterilization campaigns at the end of each year (qunzhong yundong). The core strategies used were “mandatory IUD (intrauterine device) insertion for women with one child, abortion for unauthorized pregnancies, and sterilization for couples with two or more children” (yi-huan, er-zha, san-gua).Citation2,9 Directive slogans were posted in most rural areas, such as, “It’s better to add ten cemeteries than to add one newborn” (ningtian shizuo fen, butian yige ren) and “An unplanned birth will result in birth control surgery” (gaiza buza, fangdao wuta; gailiu buliu, bafang qianniu). A few provinces, such as Sichuan and Shandong, even implemented mass sterilization campaigns in which sterilization was mandatory after one birth. Citation5 In 1983, an estimated 88 million sterilizations and 14.4 million induced abortions were performed nationwide, and during the 1980s the sterilization rate (46.33%) and the induced abortion rate (the number of abortions per 1000 women aged 15–49, at 56.07%) peaked. The total fertility rate dropped from 2.92 in 1979 to 2.42 in 1983 alone.Citation1

These policies and campaigns caused a popular uproar and ignited strong resistance, especially from China’s vast rural areas. In response, the government slightly modified the policy and incorporated more pragmatic reforms in April 1984 and May 1986.Citation10 First, in most rural areas, if the first child was a girl, a second birth was allowed.Citation11 Second, implementation of birth control was to adhere to the “three principles” (san wei zhu), which were “information, communication and education” to guide the public to comply with the family planning policy. Eighteen provinces began to implement this reform by the end of 1989; however, it was not well implemented in practice.Citation2 A considerable number of cadres (government officials) did not fundamentally change how they implemented the family planning policy, and the policy of mandatory “IUD/abortion/sterilization” did not change substantially. Citation3,8

In the early 1990s, the central government again strengthened its mandatory programmes on induced abortion and sterilization, the prevalence of which reached a second historical peak. Out of 30 provinces, 26 continued to enforce the policy of mandatory “IUD/abortion/sterilization”. China maintained the highest overall contraceptive usage and the highest prevalence rate of long-term contraception in the world.Citation12 The average induced abortion rate also reached a higher level (39.32%) during the period 1979–1994.

Influenced by the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) in 1994, the Chinese government initiated a client-centered policy of informed choice on contraception and a high quality of care in services (you zhi fu wu).Citation2 Married couples were entitled to informed choice concerning contraception. This policy reorientation was piloted in six selected counties in 1995, expanded to 11 provinces in 1997, and then to all 28 provinces at the end of 2000. Within the pilot areas, family planning programme enforcement became increasingly aligned with international reproductive health standards and more attention was paid to women’s right to contraceptive choice by enabling married couples to choose contraceptive methods according to their own needs. For example, the government ceased to enforce controls on indices relevant to birth control, such as the sterilization rate and induced abortion rate. Married couples were able to freely select their contraceptive method with the guidance of professionals. The pilot programme appeared to be successful and was supported by the public. Compared to the period of tightened policy in the 1980s, the 1990s were known as the period of moderate policy.Citation3

Afterwards, the central government relaxed its policy further. The government began to discourage pregnant women from having induced abortions on a large scale, and instead promoted a more relaxed policy such as the “Compensation Fee” (shehui-fuyang-fei)Footnote* and the Informed Choice policy to attenuate the dominance of the use of abortion in China up to then. In the early 21st century, the Family Planning Technical Services Regulations and the Population and Family Planning Law of 2002 again reshaped family planning policy. Although these laws adhered to the one-child policy, they granted married women new reproductive rights, such as the right to decide the timing and spacing of two births, once authorized, the right to choose their contraceptive method freely, and the right to decline a second trimester abortion. One of the most important clauses in the Population and Family Planning Law was on the Compensation Fee. It said that most unauthorized pregnancies would no longer require an induced abortion. Instead, the provincial Family Planning Bureau would collect a fine called the Compensation Fee from families who disobeyed the one-child policy, which could be as much as four to ten times the average annual family income. Citation3 To prevent possible avoidance or fraud, Hukou (household registration) would be available for the newly born child only if the fine was paid. If a child was without Hukou, s/he would be denied access to education, health care and other state welfare provisions. Although the penalty was severe, it was seen as much less severe than being forced to have an abortion in the eyes of many Chinese couples who desired more children.Citation13 In China, the preference for a son and the belief that “the more children, the more blessing” are very popular, especially among rural residents. This perception is strengthened when the disadvantage of raising only one child becomes more obvious. Thus, many couples would rather pay a heavy fee, or even escape the fine by any available means if they could not afford to pay.Citation13,14 As a result, there were at least 13 million unauthorized births (hei hu) in China from 2000 to 2010.Citation15 Although the stringency of China’s family planning policy showed geographical and demographic variation,Citation16 the integrated implementation of the Compensation Fee and Informed Choice policies transmitted an official signal that the one-child policy had flexibility and had been relatively loosened at national level.Citation3,13,17

The relative loosening of policy gave rise to a corresponding change in the overall composition of contraceptive method use by married couples, who were more likely to choose condoms and other short-term contraceptive methods.Citation18 Among married women of reproductive age (20–49 years), the prevalence rate of sterilization increased from 30.21% in 1980 to 46.47% in 1994, and declined to 31.7 % in 2010. At the same time, IUD usage increased from 39.83% in 1980 to 48.15% in 2010. Similarly, there was an increase in oral contraceptive and condom usage. Oral contraceptive use increased from 0.3% in 1980 to 0.98% in 2010, and condom use from 2.35% in 1980 to 9.32% in 2010.Citation8 Therefore, the decade 2000–2010 was known as the period of loosened policy.Citation3

Compared to long-acting contraceptive methods, the higher failure rate of short-term contraceptive methods would have resulted in an increase in unwanted pregnancies, and a corresponding change in the induced abortion rate.Citation19 However, two controversial questions remain: whether the loosened family planning policy led to an increase or decrease in the induced abortion rate nationwide, and whether a real correlation existed between the two. He (2006) and Bai et al (2007) argued that the looser family planning policy resulted in a significant increase in the number of induced abortions, based on small samples drawn from the city of Wenzhou (Zhejiang province) and the city of Suzhou (Jiangsu province) respectively.Citation14,20 However, opposing views also exist. Based on several different provincial samples, Li et al. (1999), Gao & Xiao (2002) and Wang (2011, 2012) argued that the abortion rate had decreased, and that in several provinces the less stringent the family planning policy was, the less likely a woman was to undergo an induced abortion.Citation21–24 These conflicting findings do not agree because of differences in study indicators, type of data collected and methods of analysis. Furthermore, the findings on both sides were limited by small sample size and lack of national representativeness. Thus, these studies did not clarify the association between the abortion rate and family planning policy nationwide. The goal of the present study was to explore the determinants of induced abortion choice at the individual level, especially those choices made under the influence of the family planning policy, based on representative nationwide data.

Materials and methods

Data

Given that China’s family planning policy is targeted at married women and men of reproductive age, this study also focused on married women of reproductive age (20–49 years old) in China. A descriptive statistical analysis was conducted using secondary data from the Yearbook of China’s Population and Family Planning (1984–2011), compiled by the National Population and Family Planning Commission (NPFPC) of the People’s Republic of China.Citation11 These data have been used to estimate the incidence of induced abortion.Footnote* To calculate total abortion rates, estimates of the number of married women of reproductive age (20–49 years) were used in this study. By employing standardization by grand mean centering methods, it was possible to make comparisons from multiple data sources.

In addressing the determinants of induced abortion use, individual-level raw data from three representative decennial surveys (1988, 2001, 2006) were used, representing a sample of 2,100,000 women aged 15–57 in 1988, 39,600 in 2001, and 33,257 in 2006, respectively. These data were obtained from the National Family Planning and Reproductive Health Surveys in China, conducted by the National Population and Family Planning Commission (NPFPC) in July 1988, July 2001, and July 2006.

Variables and models

The dependent variable was induced abortion events (a count variable), which showed a high incidence of zero counts and a negative binomial distribution. Therefore, a zero-inflated negative binomial model (ZINB) was employed to model the numbers of induced abortion events per capita.

Previous studies have found that the frequency of induced abortions in China was jointly influenced by individual factors and community factors. At the individual level, women who were well educated, lived in cities, and were of Han nationality had a higher likelihood of induced abortion.Citation25,26 The sex of the youngest living child was another individual indicator. The likelihood of induced abortion was also significantly higher for women whose youngest living child was a daughter than for those whose youngest living child was a son. This phenomenon could partly be explained by son preference, which is deeply rooted in Chinese childbearing cultures.Citation27,28 In order not to violate the one-child policy, some couples would resort to selective abortion of female fetuses. As a result, sex-selective abortions increased and discrimination against daughters was exacerbated.Citation29,30 At the community level, previous studies focused on how induced abortions were correlated with a region’s economic development, urbanization, and hygienic conditions.Citation31–34

However, previous studies disregarded the influence that the family planning policy had on induced abortion in different periods. To implement the family planning policy, local governments relied heavily on enforced induced abortions to control local birth rates. Abortions were enforced for pregnancies that resulted from failure of contraception and violation of family planning policy.Citation35,36 Qiao (2004) found out that most pregnancies terminated in rural areas were in fact unauthorized pregnancies outside the family planning policy.Citation37

Therefore, this study’s regression models took the stringency of the family planning policy as an explanatory variable. Because it was not directly measured, the models employed the survey years as instrument variables for the family planning policy variable. The questionnaire design and survey menu made it possible to use the survey years to indicate the stringency of the family planning policy in China.Citation1 Consequently, to measure the stringency of the family planning policy, this study followed a previous article,Citation8 developed an ordinal variable of survey years as instrument variables, which are tightened, moderate, and loosened. Other variables in these models were acquired by direct measurement.

To explore the influence of the stringency of the family planning policy, this study selected sampling units of married women who had pregnancy and abortion histories during the period 1979–1988 (tightened policy) from 1988 survey, during the period 1994–2000 (moderate policy) from wave 2001, and during the period 2001–2006 (loosened policy) from wave 2006. Due to differences in the questionnaires used, samples from Tibet were dropped. After validation testing and weighted data merging, 59,007 samples (married women aged 20–49 years) remained for use in modeling.

Based on a literature review, grounds of statistical significance (Wald test at 5% significant level), and likelihood ratio tests in nested models, the parsimony models reported on induced abortion utilize the following explanatory variables: individual ethnicity (Han, other), number of living children, age, Hukou (household registration — urban, rural), educational attainment (primary school and below, middle school, high school, college and above), living region (east area, middle area, west area), family income, sex of youngest living child (boy, girl), and stringency of family planning policy (tightened, moderate, loosened).

Results

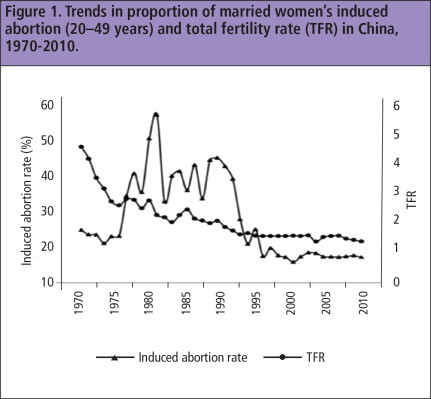

displays overall trends in the proportion of induced abortions among married women under the family planning policy from 1970 to 2010. As shows, the number of induced abortion cases was approximately 272 million, and the rate of induced abortions in China reached its peak (56.07%) in 1983 and its lowest value (18.04%) in 2001, with an average annual rate of 28.95%. The figure illustrates four phases, distinguished by various levels and trends in induced abortion.

Figure 1 Trends in proportion of married women’s induced abortion (20–49 years) and total fertility rate (TFR) in China, 1970–2010.

The first phase (1970–1983) was characterized by a rapid increase: the induced abortion rate increased from 19.38% in 1970 to its highest level of 56.07% in 1983 (approximately 14.37 million cases), and the average induced abortion rate was 30.90% ± 11.23%. In the second phase (1984–1993), the induced abortion rate was fairly steady, increasing slightly to an average rate of 40.03% (±4.44%). The number of induced abortion cases was approximately 13.08 million in 1991 (the induced abortion rate was approximately 44.95%, its second highest level). During the third phase, a slow downward trend in the induced abortion rate existed from 1994 to 2000, falling from 29.04% to 19.30%. The average induced abortion rate during this phase was 22.64% (±5.05%). The fourth phase was a stable period with an average rate of 19.47% (±0.66%) from 2001 to 2010.

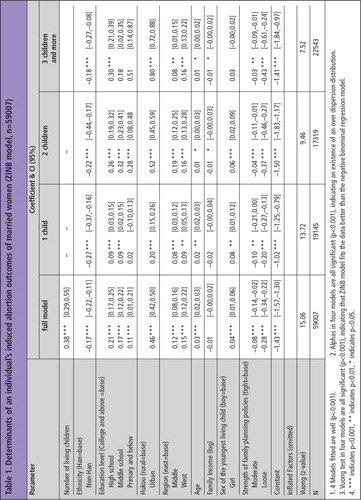

Table 1 presents the results of fitting a parsimonious ZINB model with a subsequent likelihood ratio test for nested models (p<0.001) and a Vuong test of the model (p<0.001). It is safe to draw the conclusion that the ZINB model fits the data well. Parameter estimates for the ZINB model are presented in Table 1 for the three family planning policy variables (tightened, moderate and loosened) and other demographic variables.

Table 1 Determinants of an individual’s induced abortion outcomes of married women (ZINB model, n = 59007) Notes: (1) 4 Models fitted are well (p < 0.001). (2) Alphas in four models are all significant (p < 0.001), indicating an existence of an over dispersion distribution. (3) Vuong test in four models are all significant (p < 0.001), indicating that ZINB model fits the data better than the negative binominal regression model. (4) *** indicates p < 0.001, ** indicates p < 0.01, * indicates p < 0.05.

The results indicate that family planning policy and individual characteristics (ethnicity, the number of living children, age, education level, region, Hukou and the sex of the youngest living child) are significant determinants of induced abortion outcomes (p<0.05). After using a series of models (one-child model, two-children model, three-children and more model) to check robust stability, the results show that the influence of the parameters is systematically stable in contrast to the full model mentioned above.

With other variables held constant, the following emerged:

| • | the more living children a woman had, the more likely it was that she had an induced abortion during the period studied; | ||||

| • | the greater the percentage of ethnic minorities in a sub-region, the less frequent the occurrence of induced abortion was; | ||||

| • | the higher the education level of a woman, the less likely she was to undergo an induced abortion; | ||||

| • | women living in urban areas were more likely to undergo induced abortions than women living in rural areas; | ||||

| • | women living in the middle and western regions were more likely to undergo induced abortions than women living in the eastern regions; and | ||||

| • | a married woman whose youngest living child was a girl was more likely to undergo an induced abortion than a married woman with the same number of children but whose youngest living child was a boy. | ||||

Furthermore, as expected, the influence of family planning policy on individual induced abortions was found to be substantial. Policy stringency was found to be a significant determinant of count responses. The weaker the family planning policy in force, the less likely a woman was to undergo induced abortion. The incidence rate ratio (IRR) of induced abortion for married women under the loosened policy was only 75.57% (=e–0.28), and was far less than that under the tightened policy.

Discussion and conclusions

Although the data show that induced abortion rates among married Chinese women fluctuated during the period 1970–2010, there has been a significant decrease in recent years, which was further demonstrated by regression analysis. This study showed an association between the incidence of induced abortion, the stringency of family planning policy, and the characteristics of individual women. With the relaxation of enforcement of the national family planning policy, the likelihood of married women undergoing an induced abortion decreased by 24.43% (range = 1–75.57%). Thus, the correlation between the strength of family planning policy and the frequency of induced abortion was validated.

The regression models developed also show that a woman with more children was more likely to undergo an induced abortion, in large part because the family planning programme imposed induced abortions for unauthorized pregnancies on all women of childbearing age in China after 1979, as a population control method, along with mandatory IUD insertion for women with one child and sterilization for couples with two or more children.

A policy such as this has a strong element of inertia, and even now, there is still a mandatory requirement for induced abortion in some remote areas. The greater the percentage of ethnic minorities in a sub-region, the lower the incidence of induced abortion. This association is due in part to the fact that induced abortion is mainly promoted to prevent second and third births in the Han sub-region, and the number of allowable births in the Han sub-region is more strictly limited than in ethnic minority areas.Citation18

Higher education levels among married Chinese women of reproductive age were found to be related to a lower likelihood of having undergone induced abortions. This association is due, to some extent, to individuals with more education being more likely to use contraceptive methods effectively and to want fewer children than women with less education.Citation8

Women in the middle and western regions of China were more likely to have undergone induced abortions than women in the eastern region of the country. This association is due, on one hand, to the stricter promotion of family planning policy in the middle and western regions, and on the other hand, to a stronger preference for male children in the middle and western regions than in the eastern regions.Citation18,37

Women living in rural areas were less likely to undergo induced abortions than women living in urban areas. This association is partly due to the fact that women in urban areas are more tightly constrained by the one-child policy than women in rural sub-regions, and that urban women are subject to a Danwei (work unit) institute. In disobeying or undermining the one-child policy, women in urban areas would be subject to administrative sanctions by their affiliated Danwei, and their Danwei would in turn also be severely punished by senior units.Citation18

In addition, married women whose youngest living child was a girl were more likely to undergo an induced abortion than married women with the same number of children whose youngest living child was a boy. This association is partly attributable to the fact that women with a greater desire for sons may be more willing to have abortions if they are carrying a female fetus, especially women living in rural China or in relatively poorer areas whose first child was a girl.Citation18,32

Under the loosened policy, married women were significantly less likely to undergo induced abortions than under the tightened policy. Prior to 1994, the Chinese Family Planning Programme intervened administratively in individual childbearing behaviour via the mandatory one-child policy, provision of free contraceptive services, and organizational safeguards. Most married women, under such conditions, had little choice but to undergo induced abortions if they had had more pregnancies than local rules allowed. After 1994, women were given the option of “paying a heavy penalty fee” for more births, which reduced the frequency of induced abortions as well as administrative penalties, relocation and demotion.Citation17 In 2000, the central government established the Compensation Fee for unauthorized births, to relieve the economic burden that additional births impose on society. In 2011, the Compensation Fee had brought in an income of approximately 20 billion yuan to local governments across the country.Citation38 Despite the opacity of the fines and the imprecision of the unplanned birth registration, there were at least 13 million unauthorized births in 2000–2010.Citation15 The more unauthorized births, the less likely it would be that a woman would undergo a forced abortion.

There are several limitations of the present study. Despite the use of decennial national representative data and many predictors, the causal effects were not proven and other factors on abortion rates were not measurable and verifiable, limited by the data. For example, previous studies have disputed whether widespread use of emergency contraception could have reduced abortion rates.Citation39–41 While emergency contraception could be an important predictor, there is a lack of national official data on emergency contraceptive use in China.

The “loosened” policies in place since 2002 have become the core strategy of the Chinese central government to maintain a low fertility rate. Women’s reproductive rights have gradually come to be recognized, and the abortion rate has been decreasing nationwide. However, the political aim of eradicating mandatory abortions is far from being achieved. In certain less developed and remote areas (Lao, Shao, Bian, Qiong), unplanned pregnancies, once discovered or reported, are likely to end with mandatory abortions. This reminds us that studies on the incidence of induced abortions should not simply look at the effects of stringent policies, but also at improving awareness of reproductive health and rights and providing safe and effective contraceptive methods.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the valued comments, suggestions and corrections on earlier drafts of this article from Min Li, University of Florida. Special thanks to Yudong Zhang, University of Chicago, for her help in proofreading. This study was supported with funding from the Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University, China, and the Program for Innovation Research in the Central University of Finance and Economics, China.

Notes

* According to the Population and Family Planning Law of the People’s Republic of China and the Management Provisions of Imposing the “Compensation Fee” promulgated by the State Council, those who experience any of the following four circumstances should pay this fee to their local government: (1) giving birth to a baby out of wedlock; (2) giving birth to a baby not in compliance with the regulations; (3) giving birth to a second baby in compliance with the regulations, but unapproved; or (4) giving birth to a third (or subsequent) baby not in compliance with the regulations.

* The data are from published secondary statistics. There is no information in the data sources that can be used to identify respondents, and human subject protection is not an issue here. Furthermore, as a state organization, the NPFPC has an IRB to approve data collection related to human subjects. These disclaimers also apply to the data from the National Family Planning and Reproductive Health Surveys in China used here.

References

- National Population and Family Planning Commission of P.R. China & China Population and Development Research Centre. Collection of Commonly Used Population and Family Planning Data of China. 2011; China Population Publishing House: Beijing.

- P Peng. Encyclopedia for Family Planning of China. 1997; China Population Publishing House: Beijing.

- W Zhang. National Population and Family Planning Commission of P.R. China. History of Population and Family Planning. 2007; China Population Publishing House: Beijing.

- X Qian. China’s population policy: theory and methods. Studies in Family Planning. 14: 1983; 295–301.

- M Sun. The History of Family Planning. 1990; North China Women and Children Press: Changchun.

- J Coale. Recent trends in fertility and nuptiality in China. Science. 251: 1991; 389–393.

- S Greenhalgh, J Bongaarts. Fertility policy in China: future options. Science. 215: 1987; 1167–1172.

- C Wang. Trends in contraceptive use and determinates of choice in China 1980–2010. Contraception. 85(6): 2012; 570–579.

- W Zhang, X Cao. Family planning during the economic reform Era. Z Zhao, F Guo. Transition and Challenge: China’s Population at the Beginning of the 21st Century. 2007; Oxford University Press: London.

- X Peng. Demographic Transition in China. 1991; Clarendon Press: Oxford.

- Y Zeng. Options for fertility policy transition in China. Population Development and Review. 33: 2007; 215–246.

- C Wang, X Zheng, G Chen. The longitudinal trends of contraceptive behavior among married people of reproductive age in China. Population Journal. 16(4): 2007; 57–62.

- Z Chen. The Procreative Right and the Institution of Social Compensate Fee. 2011; Law Press China: Beijing.

- A He. Thinking on the increment number of induced abortion by the change of informed choice policy and contraceptive methods. Maternal and Child Health Care of China. 10: 2006; 1378–1379.

- D Yao. The mysterious social compensation fee. China Economic Weekly. 19: 2012; 31–35.

- B Gu. China’s local and national fertility policy at the end of the twentieth century. Population and Development Review. 33(1): 2007; 129–147.

- C Wang. History of the Chinese contraception in family planning program 1970–2010. Contraception. 85(6): 2012; 563–569.

- C Wang. Life course of contraceptives under China’s family planning: 1970–2010. Sea of Knowledge. 2: 2011; 34–41.

- C Marston, J Cleland. Relationships between contraception and abortion: a review of the evidence. International Family Planning Perspectives. 29(1): 2003; 6–13.

- M Bai. An investigation on the informed choice policy influence on married women’s contraceptive practice in Suzhou. Chinese Journal of Family Planning. 4: 2007; 9–12.

- Y Li. Impact of improving care quality on the incidence of induced abortion. Reproduction and Contraception. 6: 1999; 38–43.

- E Gao, S Xiao. Contraceptive Counseling Manual of Contraception Service and Informed Choice. 2002; China Population Publishing House: Beijing.

- C Wang. The effects of the client-centered policy of informed choice of contraceptives for induced abortion in China. Population and Development. 3: 2010; 17–26.

- C Wang. A test of the impacts of the client-centered contraceptive policy of informed choice on induced abortion in China. South China Population. 26(1): 2011; 7–13.

- Z Zheng. An analysis of the reproductive health status of Chinese women at childbearing age with an application of reproductive health indicators. Population Research. 6: 2000; 8–21.

- L Pang, Y Sun, X Zheng. A comparative analysis of the level and determinants of induced abortion of married Chinese women. Collection of Papers of the 2001 National Family Planning and Reproductive Health Survey. 2004; China Population Publishing House: Beijing, 204–215.

- F Arnold, Z Liu. Sex preference, fertility, and family planning in China. Population and Development Review. 12: 1986; 221–246.

- R Murphy. Fertility and distorted sex ratios in a rural Chinese county: culture, state, and policy. Population and Development Review. 29(4): 2003; 595–626.

- S Greenhalgh, J Li. Engendering reproductive policy and practice in peasant China: for a feminist demography of reproduction. Signs. 20: 1995; 601–641.

- K Johnson. The politics of the revival of infant abandonment in China, with special reference to Hunan. Population and Development Review. 20: 1996; 77–98.

- R Huang, S Yu. Abortion and its determinants for Chinese married childbearing women. Collection of Papers of the 1997 National Population and Reproductive Health Survey. 2000; China Population Publishing House: Beijing, 267–275.

- W Chen. Sex preference and fertility behaviors of Chinese women. Population Research. 2: 2002; 14–22.

- X Qiao. Analysis of induced abortion of Chinese women. Population Research. 3: 2002; 16–25.

- P Löfstedt, S Luo, A Johansson. Abortion patterns and reported sex ratios at birth in rural Yunnan. China. Reproductive Health Matters. 12(24): 2004; 86–95.

- S Rigdon. Abortion law and practice in China: an overview with comparisons to the United States. Social Science and Medicine. 42(4): 1996; 543–560.

- D Wang, H Yan, Z Feng. Abortion as a backup method for contraceptive failure in China. Journal of Biosocial Science. 36(3): 2004; 279–287.

- X Qiao. Son preference, sex selection and sex ratio at birth. Chinese Journal of Population Science. 1: 2004; 14–22.

- N Lv, Q Cui. Keep track of the mysterious social compensation fee. People’s Digest. 10: 2013; 36–37.

- S Wu, H Qiu. Current status and suggestions on induced abortion in China. Acta Academiae Medicinae Sinicae. 32(5): 2010; 479–482.

- A Glasiera. Advanced provision of emergency contraception does not reduce abortion rates. Contraception. 69(5): 2004; 361–366.

- M Hayes, J Hutchings, P Hayes. Reducing unintended pregnancy by increasing access to emergency contraceptive pills. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 4: 2004; 203–208.