Abstract

Abstract

In Brazil, to have a legal abortion in the case of rape, the woman’s statement that rape has occurred is considered sufficient to guarantee the right to abortion. The aim of this study was to understand the practice and opinions about providing abortion in the case of rape among obstetricians-gynecologists (OBGYNs) in Brazil. A mixed-method study was conducted from April to July 2012 with 1,690 OBGYNs who responded to a structured, electronic, self-completed questionnaire. In the quantitative phase, 81.6% of the physicians required police reports or judicial authorization to guarantee the care requested. In-depth telephone interviews with 50 of these physicians showed that they frequently tested women’s rape claim by making them repeat their story to several health professionals; 43.5% of these claimed conscientious objection when they were uncertain whether the woman was telling the truth. The moral environment of illegal abortion alters the purpose of listening to a patient — from providing care to passing judgement on her. The data suggest that women’s access to legal abortion is being blocked by these barriers in spite of the law. We recommend that FEBRASGO and the Ministry of Health work together to clarify to physicians that a woman’s statement that rape occurred should allow her to access a legal abortion.

Résumé

Au Brésil, pour avorter légalement en cas de viol, la déclaration de la femme affirmant que le viol s’est produit est considérée comme suffisante pour garantir le droit à l’avortement. L’objectif de cette étude était de comprendre la pratique et les opinions sur l’avortement en cas de viol parmi les gynécologues-obstétriciens brésiliens. Une étude à méthodologie mixte a été réalisée d’avril à juillet 2012 auprès de 1690 gynécologues-obstétriciens qui ont répondu à un autoquestionnaire électronique structuré. Dans la phase quantitative, 81,6% des médecins exigeaient des rapports de police ou une autorisation judiciaire pour assurer les soins demandés. Des entretiens téléphoniques approfondis avec 50 de ces médecins ont montré qu’ils vérifiaient fréquemment l’affirmation de viol des femmes en les faisant répéter leur histoire à plusieurs professionnels de santé ; 43,5% d’entre eux invoquaient l’objection de conscience quand ils n’étaient pas sûrs de la véracité des dires de la femme. L’environnement moral de l’avortement clandestin modifie le but de l’écoute d’une patiente : ce n’est plus de fournir des soins mais de la juger. Les données suggèrent que l’accès des femmes à l’avortement légal est bloqué par ces obstacles, en dépit de la loi. Nous recommandons que la FEBRASGO et le Ministère de la Santé collaborent pour faire comprendre aux médecins que la déclaration d’une femme affirmant qu’un viol s’est produit devrait lui donner accès à un avortement légal.

Resumen

En Brasil, para tener un aborto legal en el caso de una violación, la declaración de la mujer de que fue violada es suficiente para garantizar su derecho al aborto. El objetivo de este estudio fue entender la práctica y opiniones de gineco-obstetras en Brasil con relación a la prestación de servicios de aborto en el caso de violación. Desde abril hasta julio de 2012, se realizó un estudio de métodos combinados, con 1690 gineco-obstetras que respondieron a un cuestionario electrónico estructurado. En la fase cuantitativa, el 81.6% de los médicos requerían una denuncia policial o autorización judicial para garantizar los servicios solicitados. Las entrevistas telefónicas a profundidad con 50 de estos médicos mostraron que a menudo verificaban la declaración de violación por parte de las mujeres pidiéndoles que repitieran su historia a varios profesionales de la salud; el 43.5% de estos invocaron objeción de conciencia cuando no estaban seguros de que la mujer estuviera diciendo la verdad. El ambiente moral del aborto ilegal cambia el propósito de escuchar a una paciente: de brindarle atención a juzgarla. Los datos indican que el acceso de las mujeres a los servicios de aborto legal está siendo bloqueado por estas barreras a pesar de la ley. Recomendamos que FEBRASGO y el Ministerio de Salud trabajen conjuntamente para aclararles a los médicos que la declaración de violación por parte de la mujer debe permitirle acceso a un aborto legal.

The 1940 Brazilian Penal Code only authorizes abortion in case of rape or when a woman’s life is at risk.Citation1 A decision of the Brazilian Supreme Court in 2012 made abortion legal also in the case of fetal anencephaly.Citation2 Despite the penal restrictions, the magnitude of clandestine abortions in the country is high. A national study with direct methods of collecting information conducted in 2010 revealed that 15% of women between the ages of 18 and 39 had had at least one abortion.Citation3

Current regulations for abortion services were formulated in the 1990s; yet in 1996, there were only four public health care facilities providing access to legal abortions in the country.Citation4 In 1999, the Brazilian Ministry of Health released technical guidance on Prevention and Treatment of Injuries Resulting from Sexual Violence against Women and Adolescents, which stimulated the organization of new services. In 2001, 63 hospitals, in 24 of the 27 states in Brazil, were registered to provide abortions under this guidance. Nevertheless, the majority were concentrated in the state capitals and big cities, which constitutes a barrier to access in a country with continental proportions.Citation4,5

Women’s access to legal abortion services can be made difficult for several reasons: from the conscientious objection of health care professionals to the demand for additional medical exams, police documents, or judicial authorization, all of which we treat as “barriers”. The imposition of barriers can cause harm to women mainly through the delay in providing health care.Citation6,7 In Brazil, the Health Ministry regulations exempt rape victims from having to submit a police report, expert medical opinion, or judicial authorization. The only required document for abortion in the case of rape is the signed consent of the woman.Citation8

Similar to international guidelines, the Brazilian Code of Medical Ethics and the technical standards of the Health Ministry recognize the right of the physician to conscientious objection.Citation8,9 The moral basis for conscientious objection to abortion seems to be different in countries with a Catholic/Christian tradition, as in Brazil, where the law is restrictive and the abortion referral services are public and mainly available in large cities.Citation10 In this situation, the refusal to provide an abortion can be an additional barrier for women who have been raped.Citation6

Studies of the knowledge and opinions of obstetrician-gynecologists about abortion in the beginning of the 2000s in Brazil did not investigate their concrete care practices in the abortion services. However, a study in 2003 among 4,323 obstetrician-gynecologists on the national regulations on abortion found that around two-thirds of the physicians believed judicial authorization was necessary to provide an abortion.Citation11 Similar findiings were obtained in another study among 572 obstetrician-gynecologists, of whom only 48% demonstrated adequate knowledge of the legal requirements for abortion.Citation12 As for public opinion, a recent study has shown that, although Brazilians diverge in relation to when abortion should be legal, most agree that women should not be imprisoned for such practice.Citation13

Brazilian obstetrician-gynecologists are professionals with a central position in women’s reproductive and sexual health care, as only physicians can perform abortions. International studies show that the main reason claimed by physicians for conscientious objection to abortion is religious convictions.Citation14,15 Few studies have analysed the reality of conscientious objection in Brazil. In 2012, a qualitative study with obstetrician-gynecologists from a referral service for legal abortion in Salvador, a city in the northeast of Brazil, showed that the fear of being prosecuted and the stigma of abortion were the principal reasons for physicians to refuse to provide an abortion.Citation16

There are no national data on how these health professionals proceed morally when a female rape victim seeks an abortion. There is neither evidence about the barriers women face nor, most importantly, the impact of physicians’ refusal to provide the service. This article describes the results of a national study that aimed to understand the opinions and practices of Brazilian obstetrician-gynecologists regarding abortion in the case of rape.

Methodology

A mixed-method study was conducted among physicians affiliated with the Brazilian Federation of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (FEBRASGO), the largest medical organization of obstetrics and gynaecology in the country. The study was conducted in two phases between April and July 2012 — first a quantitative phase using an electronic questionnaire, then a qualitative phase using in-depth telephone interviews.

In the first phase, the 15,000 members of FEBRASGO received an electronic invitation to participate, sent by FEBRASGO, and a convenience sample of respondents was obtained. A self-completed questionnaire was available at a web page for the three months between April and June 2012. Each month for three months a new invitation was sent out. The electronic survey was structured and anonymous and included questions about age, sex, residence, religion, time of practice, and history of experience providing care for women who had been victims of rape. Thereafter, the instrument had two questions about the documents that a woman must provide in order to access abortion services and about physician’s conscientious objection. These two questions allowed multiple alternatives. A pre-test of the questionnaire was obtained in two stages with the participation of academic specialists and 35 obstetrician-gynecologists. The data from the pre-test were discarded.

In this quantitative phase, the data were tabulated in a Microsoft Excel 2007 spreadsheet for the descriptive analysis of sociodemographic information. Questions that allowed multiple answers were categorized with values: 0 (no) and 1 (yes), and the answers were tabulated (only the woman’s account, only a police report, the woman’s account + a police report, etc). The frequency and percentage of the answers were computed and those cited most frequently were shown in tables.

In the second phase, the physicians from the quantitative phase were invited to participate in qualitative, in-depth interviews and were asked to provide their email address and/or telephone number for later contact. Of the 582 physicians of the total 1,690 who indicated that they would be interested in continuing their participation, 50 were selected based on the criteria that they had previously provided abortion care for women who had been raped, were from different ages, (above and below 50 years of age), sexes and geographic regions (ten each from the five main regions in the country). In June and July 2012, in-depth telephone interviews were conducted with the 50. A semi-structured instrument was used with all of the participants. Data were collected using 15 questions, organized in three sections: 1) “Which documents must a woman provide in order to receive an abortion?”; 2) “What is your position in relation to conscientious objection to abortion?”; and 3) “Have you ever refused to perform a legal abortion?”

In this qualitative phase, the interviews were recorded and transcribed. The transcripts were read and codified by two researchers (a physician and a social scientist) independently. The data were tabulated using an instrument with five questions about the experience of the physicians with health care for female rape victims, the documents required for abortion, and conscientious objection. The researchers compared the information and when there were discrepancies, the analysis was discussed.

Informed consent was obtained in both phases of the research. In the quantitative phase, it was requested electronically, and in the telephone interview, the participants agreed orally. In the electronic questionnaires as well as the interviews, the participants remained anonymous. In order to guarantee anonymity, the participants’ responses are not separated by state or region of the country. The study was authorized by FEBRASGO and approved by the ethics committee of the University of Brasilia.

Findings and discussion

Phase 1: respondents’ characteristics

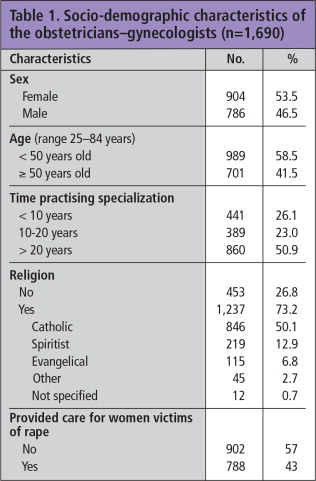

The questionnaire was answered by 1,690 physicians (11.3% of those who had received an invitation to participate in the study). Slightly more than half (Table 1) were women (53.5%), 58.5% were under the age of 50, and 50.9% had been practicing their specialization for more than 20 years. Half were from the Catholic faith (50.1%); 26.8% did not identify with any particular religion. They came from all of the states in the country, with the majority (57.2%) residing in the Southeast Region, which has the highest concentration of physicians in Brazil. 43% said that they had previously provided abortion care for female rape victims.

Creating barriers to abortion in the case of rape

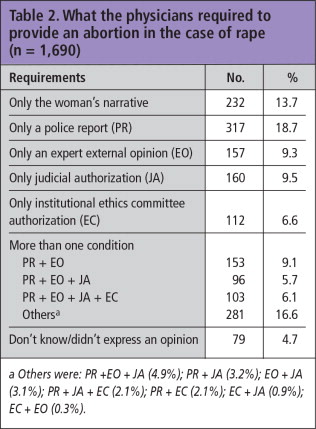

Only 13.7% of the physicians trusted the woman’s narrative about the rape on its own in order to guarantee her right to abortion. Almost half (44.1%) requested at least one document not required by law in order to agree to the abortion, such as a police report (18.7%), judicial authorization (9.5%), expert external medical opinion (9.3%), or even authorization by the institutional ethics committee (6.6%). For 37% of the physicians, the woman had to obtain and present two or more such documents to obtain the abortion (Table 2).

Table 2 What the physicians required to provide an abortion in the case of rape (n = 1,690) a Others were: PR + EO + JA (4.9%); PR + JA (3.2%); EO + JA (3.1%); PR + JA + EC (2.1%); PR + EC (2.1%); EC + JA (0.9%); EC + EO (0.3%).

Even in countries where abortion is legal on broader grounds, a number of barriers often exist to block or complicate women’s access to abortion. There are logistical barriers (such as a lack of services in rural areas and lack of trained professionals),Citation17 social barriers (such as women’s lack of knowledge about the availability of services and the right to abortion),Citation6 and administrative barriers (such as a 24-hour waiting period or mandatory counselling, often from other professionals, to discuss the “risks” of the procedure or adoption options).Citation18,19

The fact that such a high percentage of physicians (81.6%) said they demanded documents not required under the national abortion regulations can be considered a major barrier to access. While this study did not explore in depth why the physicians felt they had to impose such barriers, some of them did express the fear of being stigmatized, given the restrictive national scenario on abortion. The possibility that they were acting deliberately to block women’s right to a legal abortion cannot be ignored, but they would probably not have expressed this freely in a phone interview. Even though knowing their reasons is important to be able to influence their thinking, the outcome is that barriers like this can cause harm to women, including the risk to her mental health of the stress and the delay while she gets the authorization(s) together.Citation20

Willingness to provide a legal abortion in the case of rape

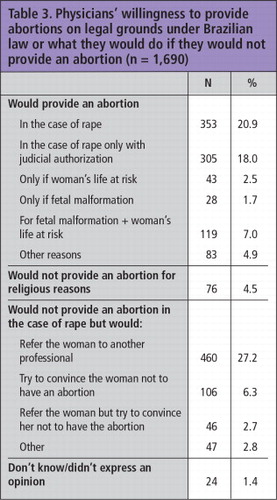

Table 3 shows that nearly one half (43.5%) of the 1,690 physicians said they would not provide an abortion in the case of rape. Only 4.5% of the refusals were justified for religious reasons. For 27.2% of them, the refusal to provide abortion themselves would not impede them from referring the woman to another physician. On the other hand, 20.9% of them indicated that they would provide an abortion when the pregnancy was the result of rape. An additional 18% also said they would do so, but only with judicial authorization (Table 3). Furthermore, only 11.2% said they would provide an abortion on other legal grounds only, i.e. fetus with anencephaly (1.7%), threat to the woman’s life (2.5%), or both (7.0%).

Table 3 Physicians’ willingness to provide abortions on legal grounds under Brazilian law or what they would do if they would not provide an abortion (n = 1,690).

Conscience objection may be understood as the individual right of the physician. However, the duty to provide care is also a professional responsibility – and women have the right to receive adequate health care when seeking an abortion in the case of rape.Citation7,21 Empirical studies conducted in other countries have shown that the majority of physicians who refuse to provide abortion on the grounds of conscientious objection believe they should also justify their reasons and refer the woman to another service or professional.Citation22,23 Male physicians and those who claim a religious affiliation are the ones who most frequently do not inform the woman of all of the options available to her, even refusing to refer her to another professional.Citation14,15

A 2004 study among Brazilian 4,261 obstetrician-gynecologists showed that 65% thought there should be a liberal review of Brazilian legislation on abortion.Citation11 Similar data were obtained in another study, in 2005, in which physicians who supported more liberal abortion laws were also those who had the greatest knowledge about abortion legislation.Citation12 However, there are no data about conscientious objection to abortion among Brazilian obstetrician-gynecologists. Many physicians may agree with more liberal laws on abortion but also refuse to provide an abortion.

Phase 2: Qualitative interviews

81.6% of the 1,690 physicians said they demanded documents not required under national regulations for a woman to obtain an abortion in the case of rape. Of the three legal grounds, rape is the one most likely to lead to raising barriers to abortion, as opposed to the threat to life, for which all of the physicians interviewed agreed that providing an abortion was a duty. Thus, in the interviews we explored the reasons given by the physicians for the imposition of barriers in relation to rape. The central question posed to them, in order to explore this, was: “How can one know the truth of the rape?” In response, physicians described the barriers they set up as strategies to verify the truth of the claim of rape.

The physicians understood the regulations, which require only the consent of the woman and a pregnancy up to 20 weeks. In general, there were no misunderstandings about this legal framework, which suggests that it is not a lack of information that leads them to create barriers to access to abortion. Our thesis is that these barriers represent an overlap between medical and police authorities’ responsibility regarding the truth of the rape. In a legal context of exceptions to illegal abortion, which characterizes the provision of abortion services in Brazil, the barriers allow the physician to act like a policeman as well as a medical professional. That is, in the absence of the need for a mandatory police report, physicians come to embody the police by imposing their own barriers for women to overcome.

Except for a few physicians who described themselves as gender-sensitive professionals, a woman’s narrative was not sufficient to alleviate what they considered to be a “risk of being prosecuted for believing a false rape story”. Their expression of fear has to be clarified here, however – it was actually more a sense of their professional honour than a fear of concrete penal intimidation. Physicians know that there is no professional penalty if the woman’s story is not true, and none of them had experienced such a situation. However, many of them did express personal convictions about the medical duty to investigate the story of the rape in order to intimidate women who sought to deceive them. To avoid the risk, the medical eye was not enough; the entire health care team had to be involved to reconstruct the history of the rape, to ensure the woman was telling the truth:

“On my team, we took the precaution to have each member listen to her story separately in order to determine if there really had been a rape.”

“She [the victim] goes through three listeners. She must tell the same story to the nurse, then to the social worker, and then to me. So there are three turns and she must tell exactly the same story regarding the time and date of the rape.”

Other tactics that create an overlap between providing medical care and carrying out a police investigation were the demand for legal documents, an ultrasound scan to confirm the chronology of the facts, and the woman exhibiting psychological trauma. The physicians said that the health care teams did not understand these multiple hoops that women had to jump through as barriers, but as “professional caution”.

The moral environment of illegal abortion imposes ambiguous feelings on physicians, including fear, stigma and shame, which alter the purpose of listening to a patient from that of providing care to passing judgement on her: “a woman could try to use the services for an abortion that is not legal… when it is in the case of rape”. The search for the truth becomes a moral duty, self-imposed by the staff, given the legal context in which abortion is a crime. The barriers are understood as responsible acts, as precautions against “being tricked by imprudent women”, and also to protect the services by offering an image of seriousness before accepting a story of rape. Thus, the crime of abortion requires physicians to reshape themselves into experts on trauma and rape.

The chronology of the violence is a central part of ascertaining the truth – “the story sometimes doesn’t match with the date [of the pregnancy], with the date of the last period, with the date of the intercourse”. A division of labour is put into force to solve the puzzle. Each member of the staff looks for a different piece of evidence – the physician looks at the pregnant body, the psychologist and the social worker examine the trauma and the social relationships between the victim and the aggressor. The Brazilian abortion regulation limits the ability to legally perform an abortion up to 20 weeks of gestation. A consequence of this limit is that the length of the pregnancy is a key piece of information for a woman to be able to access the service to compose what is called “an adequate clinical story”.

The ultrasound is seen as the incontestable proof, as if it were an official technical document that recognizes the woman’s narrative as legitimate and protects the health care team against penal prosecution. The image of the fetus, however, also has an ambiguous status – for sensitive physicians, it calms them down, but it also torments their impulse to provide care. On one hand, it is technical proof of the woman’s chronological narrative; on the other hand, small errors in the chronology can be accepted due to the fallibility of the technique – “two weeks more or less are common mistakes”. However, it can also be an affliction for the physicians: one of the psychological symptoms of trauma is difficulty remembering facts chronologically, that is, mistakes of memory could indicate the truth about the violence. Moreover, many cases of intra-family abuse are ruled by silence, and the victims, when they reach the health care services, are often in a later stage of pregnancy. The image of a fetus over 20 weeks becomes an obstacle to performing the abortion, despite the medical understanding that the abortion is necessary for the health of young girls and adolescents.

Critical to our findings, however, and what explains the routine imposition of these barriers, is the fact that the physicians made a distinction between refusing care and imposing routine barriers: none of them would refuse their “care”, but “caring” had a special meaning in their clinical services. Medical care was not the same as the medical provision of abortion – 44% of the 50 physicians with experience in “caring” for female rape victims declared that they were against abortion services. They accepted the moral duty to “care” for a female rape victim; clinical consultation and sexually transmitted disease prevention were described as neutral practices, but the medical procedure of abortion was subjected to moral rejection, i.e. it was not understood as a medical duty. Thus, there was a separation for these physicians between the medical ethos of care and the morality of abortion – all the physicians provided care, but only some of them provided an abortion in the case of rape. This tension between caring for the woman and providing an abortion, however, depended on the individual physician’s beliefs; none of them considered the right to refuse to provide “care” as comprising an institutional refusal.

As a result of the ambiguity between the individual physician’s refusal to provide an abortion as a right, and the individual and institutional obligation to provide medical assistance and care as a duty, conscientious objection is locally shaped in the public services in Brazil. The public health system allows for referral, and the physicians in charge of abortion services are not morally against providing care and abortion. Nevertheless, in specific cases in which the investigative routine makes him/her feel insecure about the truth of the rape, the physician claims the right of conscientious objection:

“Many times, I have refused to perform the abortion because it was, at least for me, clear that it was not violent, but consensual intercourse.”

As suspicion is not a reasonable reason to refuse care, 34% of the 50 physicians declared that the abortion was refused for religious reasons. Religion then gives reasonableness to the suspicion, making the refusal to provide the abortion not appear to be discriminatory against women.

Final considerations

Our findings suggest that Brazilian women who have been victims of rape and who seek an abortion are likely to confront multiple barriers. The difficulties occur mainly due to the requirement that women provide medical and/or judicial documents which are not required under the Ministry of Health’s policies. An additional obstacle is the claim of conscientious objection by physicians. The narratives of most of the physicians in this study indicated that they recognized the legal right to abortion services in the case of rape, but at the same time they postulated their right to make exceptions in the absence of a long list of proofs provided by the woman that support the truth of the rape. Several physicians put the intention of protecting themselves from stigma and professional dishonour first, reflecting Brazilian society’s ambiguity about the right to abortion in the case of rape in the context of illegality. We recommend that FEBRASGO and Ministry of Health work together to clarify to physicians that a woman’s statement that rape occurred should allow her to access a legal abortion.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the team of interviewers: Brenda Abreu, Érica Quináglia, Lina Vilela, Miryam Mastrella and Vanessa Dios; Fabiana Paranhos for logistical supervision; and João Neves for creating the electronic questionnaire and tabulating the data. We also thank FEBRASGO for sending the questionnaires to its members. The research was funded by the Safe Abortion Action Fund.

References

- Presidência da República. Casa Civil. Decreto-Lei n° 2.848, de 7 de dezembro de 1940. Código Penal [internet]. Diário Oficial da União; 31 dez. 1940. http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/decreto-lei/del2848.htm

- Supremo Tribunal Federal. Arguição de Descumprimento de Preceito Fundamental n° 54. Diário da Justiça Eletrônico n° 78/2012. http://www.stf.jus.br/portal/diarioJustica/verDiarioProcesso.asp?numDj=77&dataPublicacaoDj=20/04/2012&incidente=2226954&codCapitulo=2&numMateria=10&codMateria=4

- D Diniz, M Medeiros. Aborto no Brasil: uma pesquisa domiciliar com técnica de urna. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva. 15(Suppl.1): 2010; 959–966.

- A Faúndes, E Leocádio, J Andalaft. Making legal abortion accessible in Brazil. Reproductive Health Matters. 10(19): 2002; 120–127.

- WV Villela, MJO Araújo. Making legal abortion available in Brazil: partnerships in practice. Reproductive Health Matters. 8(16): 2000; 77–82.

- L Finer, JB Fine. Abortion law around the world: progress and pushback. American Journal of Public Health. 103(4): 2013; 585–589.

- RJ Cook, MA Olaya, BM Dickens. Healthcare responsibilities and conscientious objection. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 104(3): 2009; 249–252.

- Ministério da Saúde do Brasil. Norma Técnica: Prevenção e tratamento dos agravos resultantes da violência sexual contra mulheres e adolescentes. 2.ed. Brasília; 2005.

- Conselho Federal de Medicina. Código de Ética Médica. Brasília; 2009. http://www.cremers.org.br/pdf/codigodeetica/codigo_etica.pdf

- D Diniz. Conscientious objection and abortion: rights and duties of public sector physicians. Revista de Saúde Pública. 45(5): 2011; 981–985.

- A Faúndes, GA Duarte, J Andalaft-Neto. Conhecimento, opinião e conduta de ginecologistas e obstetras brasileiros sobre o aborto induzido. Revista Brasileira de Ginecologia e Obstetrícia. 26(2): 2004; 89–96.

- LA Goldman, SG García, J Díaz. Brazilian obstetrician-gynecologists and abortion: a survey of knowledge, opinions and practice. Reproductive Health. 2: 2005; 10.

- A Faúndes, GA Duarte, MH Sousa. Brazilians have different views on when abortion should be legal, but most do not agree with imprisoning women for abortion. Reproductive Health Matters. 21(42): 2013; 1–9.

- LH Harris, A Cooper, KA Rasinski. Obstetrician-gynecologists’ objections to and willingness to help patients obtain an abortion. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 118(4): 2011; 905–912.

- KA Rasinski, JD Yoon, YG Kalad. Obstetrician-gynecologists’ opinions about conscientious refusal of a request for abortion: results from a national vignette experiment. Journal of Medical Ethics. 37(12): 2011; 711–712.

- S Zordo. Representações e experiências sobre aborto ilegal e legal dos ginecologistas-obstetras trabalhando em dois hospitais maternidade de Salvador da Bahia. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva. 17(7): 2012; 1745–1754.

- M Greenberg, C Herbitter, B Gawinski. Barriers and enablers to becoming abortion providers: the Reproductive Health Program. Family Medicine. 44(7): 2011; 493–500.

- M Donohoe. Increase in obstacles to abortion: the American perspective in 2004. Journal of American Medical Women’s Association. 60(1): 2005; 16–25.

- J Downie, C Nassar. Barriers to access to abortion through a legal lens. Health Law Journal. 15: 2007; 143–173.

- DA Grimes. Estimating of pregnancy-related mortality risk by pregnancy outcome, United States, 1991 to 1999. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 194(1): 2006; 92–94.

- M Magelssen. When should conscientious objection be accepted?. Journal of Medical Ethics. 38(1): 2012; 18–21.

- ED Amado, MCC García, KR Cristancho. Obstacles and challenges following the partial decriminalisation of abortion in Colombia. Reproductive Health Matters. 18(36): 2010; 118–126.

- FA Curlin, RE Lawrence, MH Chin. Religion, conscience, and controversial clinical practices. New England Journal of Medicine. 356: 2007; 593–600.