Abstract

Abstract

China has had the one-child policy for more than 30 years. It reduced China’s population growth within a short period of time and promoted economic development. However, it has also led to difficulties, and this paper focuses on those which pertain to ageing and losing one’s only child. Approximately one million families have lost their only child in China. They suffer mentally and physically, and sometimes face social stigma and economic loss. What worries them most, however, is elderly care, which has become a severe crisis for the families who have lost their only children. This article draws upon several qualitative studies and 12 cases reported by the Chinese media in 2012 and 2013, and existing laws and policies for supporting those who have lost only children. It also analyses the current elderly care situation facing these families. The Chinese government has recognized the predicament and provides some help, which is increasing but is still not always adequate. To both sustain China’s economic development and limit population growth, it is essential for the government to reform the one-child policy and provide a comprehensive support system for the families who have lost their only children, including financial relief and elderly care, and work to reduce stigma against these families.

Résumé

La politique de l’enfant unique est appliquée en Chine depuis plus de 30 ans. Elle rapidement a réduit la croissance démographique et a favorisé le développement économique. Néanmoins, elle a aussi engendré des difficultés, comme le vieillissement et la perte d’un enfant unique, sur lesquelles cet article se centre. Près d’un million de familles ont perdu leur seul enfant en Chine. Elles ont souffert psychologiquement et physiquement et ont parfois subi une stigmatisation sociale et une perte économique. Néanmoins, leur plus grande préoccupation concerne les soins aux personnes âgées qui représentent désormais un grave problème pour les familles ayant perdu leur unique enfant. Cet article se fonde sur plusieurs études qualitatives et 12 cas relatés par les médias chinois en 2012 et 2013, ainsi que les lois et politiques existantes pour soutenir les parents ayant perdu leur unique enfant. Il analyse aussi la situation actuelle des soins aux personnes âgées à laquelle sont confrontées ces familles. Le Gouvernement chinois a reconnu leurs difficultés et prodigue un peu d’aide, qui augmente, mais demeure parfois insuffisante. Pour soutenir le développement économique chinois et limiter la croissance démographique, il est essentiel que le Gouvernement réforme la politique de l’enfant unique et assure un système de soutien global aux familles qui ont perdu leur unique enfant, notamment des aides financières et des soins aux personnes âgées, et qu’il s’emploie à réduire la stigmatisation dont ces familles font l’objet.

Resumen

Durante más de 30 años, China ha tenido una política de hijo único, la cual redujo el crecimiento de la población china en un corto plazo y promovió el desarrollo económico. Sin embargo, también ha causado dificultades y este artículo se enfoca en aquellas relacionadas con envejecer y perder un hijo único. Aproximadamente un millón de familias chinas han perdido un hijo único. Sufren mental y físicamente, y a veces enfrentan estigma social y pérdidas económicas. No obstante, lo que más les preocupa es el cuidado de ancianos, que ahora es una crisis grave para las familias que han perdido su hijo único. Este artículo se basa en varios estudios cualitativos y 12 casos reportados por los medios de comunicación de China en los años 2012 y 2013, así como en las leyes y políticas vigentes que apoyan a las personas que han perdido un hijo único. Además, analiza la situación actual de estas familias con relación al cuidado de ancianos. El gobierno chino ha reconocido el aprieto y ofrece alguna ayuda, que está incrementando pero no siempre es adecuada. Para sustentar el desarrollo económico de China y limitar el crecimiento de su población, es esencial que el gobierno reforme la política de hijo único y establezca un sistema de apoyo integral para las familias que han perdido un hijo único, que incluya ayuda financiera y cuidado de ancianos, y que trabaje para reducir el estigma contra estas familias.

China’s one-child policy, to control its huge population, has been in place for more than 30 years.Footnote* It has reduced China’s birth rate from 33.4 per 1,000 in 1970 to 12.1 per 1,000 in 2012. Accordingly, the natural growth rate of population in China has fallen, to 4.95 per 1,000 in 2012.Citation1 Needless to say, China’s adoption of the one-child policy has contributed a lot not only to the control of population in the world but also the rapid economic development in China.

However, the rigid implementation of the one-child policy since 1980 has also brought many problems and challenges for the Chinese people, such as the high sex ratio at birth, labour shortages and an ageing population. Of all these issues, the ageing of the population is the most urgent. According to official statistics, China has the largest aged population over age 60 in the world — 194 million at the end of 2012. The number will continue to rise annually by 10 million and will reach an estimated 487 million by 2053, accounting for 35% of China’s total population.Citation2

Among the elderly population, one group facing a possible care crisis are those who have lost their only children due to accident, disaster or disease, and who are unable to have another child because of age or low income. In China, these people are called shidu parents, i.e. parents who have lost their only children.Footnote† The official estimate of the annual number of deaths of only children aged 15–30 is 76,000. The total number of families who have lost their only children in China if children aged over 30 are included is approximately 1 million.Citation3 If child deaths below age 15 are also taken into consideration, however, the total estimated number of shidu families is 2,412,600, including 826,900 families with urban household registration and 1,585,700 with rural household registration, according to estimates based on China’s 6th National Population Census (2010).Citation4

The loss of a child is always terrible, and the loss of an only child is perhaps worse.Citation5 Yet this vulnerable group did not receive adequate attention from society or the government until recently. In official documents, shidu families and families with disabled children are described as “needy families especially affected by family planning policies”. To make their situation visible and claim their rights, some shidu families banded together and called for social and state support.

On 5 June 2012, over 80 representatives of shidu families in China submitted a petition to the National Health and Family Planning Commission, asking for economic compensation, cheaper housing in residential communities exclusively for shidu families, and designation of a special department to manage shidu issues.Citation6 Their petition, signed by more than 1,000 shidu parents, said:

“When we entered middle or old age, we unfortunately lost our only children…We are getting old day after day; who will care for us and bury us? We did not just lose our children. We lost the people who would continue our legacy, take care of us, sustain us and provide the most fundamental support for us in our old age.” Citation7

Although numerous scholars have studied elderly care in China, few have focused on elderly care for shidu families. This study seeks to enhance scholarly understanding of how China’s one-child policy affects the care of elderly shidu parents,Footnote* how Chinese government policy addresses this issue in the context of challenges in providing proper elderly care more broadly, and how elderly care of shidu families could be improved. It uses 12 cases covered by the Chinese media as examples and reviews the literature on the relevant laws and policies targeting this group of families. The article concludes with policy suggestions on improving the elderly care of shidu families.

The one-child policy in transition

The one-child policy in China has gone through three phases as regards the rigidness of its implementation. Between 1980 and 1982, the Chinese government encouraged people to have one child and rewarded those who did so, but did not punish anyone for not doing so, and there was no forced abortion. From 1982, the one-child policy became a fundamental state policy, with very rigid implementation. People who had more than one child were fined, and if they had governmental affiliations, including working in public services, universities or state-owned enterprises, they would be fired.Footnote† Policy starting from the early 2000s is still strict, but the range of people who are allowed to have more than one child has grown. Couples who are both only children themselves are allowed to have a second child. More recently, couples in which one partner is an only child became eligible to have a second child too.Footnote** However, in both cases, the couples need to go through a very complicated procedure to apply to the local government for a permit. Otherwise, they will be fined and punished. Although the one-child policy has been reformed gradually, it is still not adequate to cope with the ageing crisis. Many scholars and experts are concerned that the issue of ageing will become critical if there is no fundamental reform of the one-child policy.Citation8,9

The definition of “elderly” in relation to work and benefits

In China, in the official demographic statistics, those aged 60 and over are counted in the elderly population. Due to the surplus labour supply, however, the age of retirement in China is earlier and also gender-biased. Men retire at 60, but those engaged in work demanding physical strength or facing dangers retire at 55. Women usually retire ten years earlier than men, i.e. at 45–50.Citation10 The only exceptions for women are those who hold high-level positions in the state-owned enterprises, the public sector or are professors in universities or research institutions. “Old age” is defined as much earlier in the labour market. Men aged 50 and women aged 40 may be deemed old by employers and have great difficulty finding jobs, which is called by the Chinese government the “40–50-year old phenomenon”.Citation11 Besides age discrimination in the labour market, the trauma of losing their only children in middle age has also led many shidu parents to quit their jobs or retire at an earlier age.Citation12

The Chinese government’s policies on eligibility for relief and support for older shidu parents is generally that a mother aged 49 or older will be eligible for both the relief and the support; there is no requirement for fathers’ ages. In some regions, the father in a family with a mother aged 49 or older should be at least 60 to get the support. For single fathers, the eligible age is 49.

Difficulties and challenges in elderly care

The Chinese government foresaw the issue of elderly care arising from the one-child policy by 2020, but it has been too optimistic about the outcomes and solutions, believing the issue will be resolved through economic development, improved living conditions and increased social welfare and security.Footnote* In fact, the support and care for the elderly who are affected by the one-child policy has become an urgent social problem for China.

First, rural elderly people do not have stable sources of income to support their old age, as China’s pension system does not cover the entire elderly population. According to one national survey in 2010, only 24% of the elderly population were eligible for a pension and 41% of elderly people had to rely on their families.Citation2 At this writing, only those with urban household registrationFootnote† and full-time employment are entitled to a pension, which is 1,721 RMB per person per month (US$ 282 per month) on average. In contrast, the 50% of the Chinese population with rural household registration and living on small-scale farming are only entitled to a much lower payment, called rural old age insurance, which is 73–129 RMB per person per month (US$ 11.9–21.1 USD per month).Citation13 China’s national poverty threshold is 2,300 RMB per year (US$ 376 per year, about US$ 1 per day), so unless elderly people have their own substantial savings or financial support from their children, those with no pension or with only the rural old age insurance will be extremely impoverished.

Most elderly people lack a stable income, and the costs of medical care, elderly care and burial have been increasing dramatically. The average personal medical costs of urban and rural people in 2011 were 2,695.1 RMB (US$ 441) and 871.6 RMB (US$ 143) respectively.Citation14 Most elderly people cannot afford medical care without financial support from their children or other family members. Also the cost of burial is extremely high. There are few official data on the cost of burial, but along with booming real estate development, the price of a cemetery plot has risen ten times within ten years.Citation15 Shidu parents whose children have died of a disease are often in debt also because they have spent a lot of money on medical care for them.Citation12

There is a severe shortage in China of elderly care facilities and personnel, and the quality of elderly care is far from satisfactory. The number of senior care homes cannot be found in any official report, but the shortage such facilities is suggested by the limited number of elderly care beds available in senior care homes, which in 2010 only met the needs of 1.8% of the elderly population.Citation16 Besides inadequate care facilities, a lack of professional carers and poor management of senior care homes are two major complaints among the elderly population. At present, China has only 20,000 certified elderly carers, and the turnover rate of carers in senior care homes is extremely high, some 100–140%.Citation17 Besides, it is the rule in China that if an old person wants to stay in a senior care home, they must be sponsored by their children, even if they will pay the fees themselves. Hence, shidu parents too who can afford to stay in a senior care home will have difficulties being admitted.

Lastly, Chinese people have a long tradition of relying on their children for old age support. For Chinese children, putting their parents into a senior care home is a last resort. In a survey conducted in 2012, 49.5% of elderly people said they would like to stay with their families in their old age.Citation18 Along with the elderly care tradition, China’s various laws — including the Constitution, Law on Protection of the Rights and Interests of the Elderly, Marriage Law and Criminal Law — also make it an obligation on children to support their parents in old age. Particularly, the Criminal Law stipulates that children who will not shoulder the duty of old age support can be sentenced to up to five years in prison. Such laws raise people’s expectations of elderly care from their families and excuse the government’s absence in old age support and relief policies.

Given the one-child policy, a typical situation for a couple of two only children is that they have to take care of four elderly people, namely, their parents and parents-in-law as the major or sole carers.Citation19 For shidu parents, however, there is no such option. Their old age support cannot be guaranteed or protected by law. Losing their only children means there may be no one to care for and bury them.

In a society heavily relying on the blood line and families, shidu families face many more difficulties compared to elderly people with living children. According to one investigation published in 2013 of over 1,500 shidu families in 14 provinces of China, more than half of the shidu families had incomes below local living standards, nearly half of them suffered from depression and over 60% had chronic diseases,Citation20 unlike other elderly people.Footnote*

Qualitative studies of shidu families

Being an emotionally sensitive group, shidu families are difficult to approach. Hence, this article draws upon relevant laws and policies, several published surveys of shidu families, and 12 cases covered by the media, ten with urban household registration and two with rural household registration. Few rural cases are covered by the media, even though the countryside has a larger number of shidu families, who usually need more help. This may be because urban residents are usually more educated and better able to represent themselves. In both rural cases found, the families had lost their only children during the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, which brought them attention.

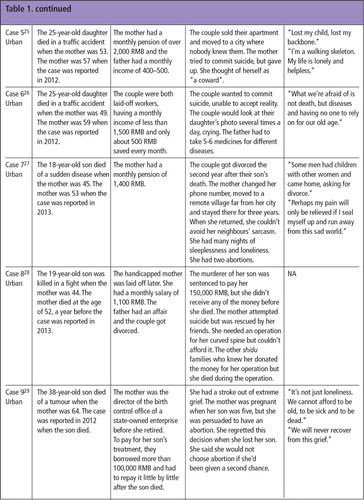

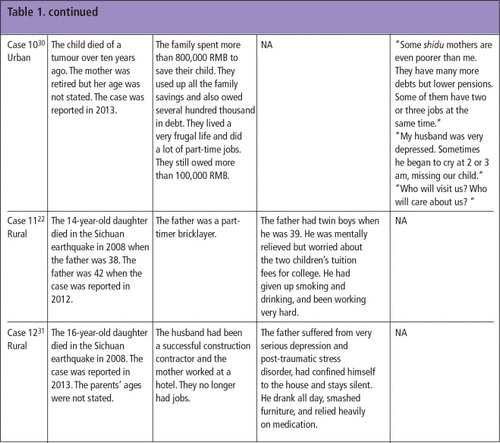

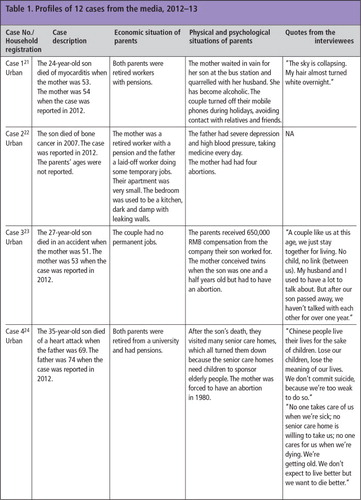

The 12 recent cases reported in the Chinese media elaborate on the current situation of some shidu families and their elderly care (Table 1). Mentally and physically struggling, and economically challenged, this group of people are most concerned about elderly care.

“What we’re afraid of is not death, but illness and having no one to rely on for our old age.” (Case 6)

Table 1 Profiles of 12 cases from the media, 2012–13 .Citation21–30,22,31

“No one takes care of us when we’re sick; no senior care home is willing to take us; no one will help if we’re dying. These are three big issues facing elderly people without their only children. We’re getting old. We don’t expect to live better but we want to die better.” (Case 4)

Many parents who have lost their only children experience severe mental suffering. They say they have lost the meaning in their lives, have been reluctant to face reality, and have cut themselves off from contact with friends and neighbours, leading to isolation. Many among these 12 cases have experienced depression, and some have post-traumatic stress disorder and abuse alcohol. Almost all of them have said they have considered suicide. Their mental suffering has also caused physical health problems, which make their care more difficult.Citation12

In Chinese tradition, losing children is sometimes thought to be a sign of bad luck. China Weekly reported that a group of shidu parents wanted to spend Chinese New Year at a restaurant. The manager of the restaurant turned them away, saying that they would bring bad luck to his restaurant.Citation25 Stigma also comes from neighbours; in Case 7, for example, the neighbours of the shidu mother said: “The parents did something evil.” Such social stigma prevents shidu families from getting help and understanding from their community, let alone elderly care and support.

In addition, losing their only child also jeopardizes the relationship between the parents, who are meant to be the most reliable support for each other as they get older. Some shidu marriages end in divorce, as happened in Cases 7 and 8. Some couples become indifferent to each other (Case 3). This is because of the loss of shared goals and the cohesive influence of a child.Citation32 If the marriage collapses, the single shidu parent is likely to have to face old age all alone.

As regards economic constraints, a survey by the Changchun Women’s Federation in 2013 found that 65% of the shidu families surveyed said they had economic difficulties.Citation33 Having no stable source of income puts shidu parents’ rights to subsistence at risk.Citation34 In Case 6, the shidu parents were both laid-off workers. They had spent a lot of money on their only daughter’s education, and just after she finished her master’s degree, on track to improve the family’s economic situation, she was killed in a truck accident on her way back from a graduation party. With a monthly income of less than 1,500 RMB (US$ 245), from which they could save about 500 RMB (US$ 82) per month, they could not afford to be ill. In Case 8, the wife was a laid-off worker and divorced from her husband. When she got ill, it was other shidu parents who raised the money for her surgery, but she died during the operation. For those whose only children died of a disease, they were often deep in debt. In Case 9, the parents spent more than 800,000 RMB (US$ 130,800), including over 100,000 RMB which they borrowed from relatives and friends, to try to cure their son’s disease. They needed to pay the debt off little by little with their pensions and income from part-time jobs.

In Case 4, the old couple had tried many senior care houses and were refused by all, because there was no one to sign the contract on their behalf. To have surgery in China, the patient’s child or an immediate family member need to sign a consent letter. Again, shidu parents face this dilemma.

Thus, the lives of shidu parents have been greatly affected by China’s one-child policy. Some shidu mothers (Cases 2, 3, 4, 7 and 9) had had abortions to conform with the one-child policy. All were regretful of this fact, given the loss of their only children, but they did not really have any other choice at the time, as the one-child policy was rigidly implemented.

Policies for elderly care of shidu families

Recognizing shidu families and families with a disabled only child as a special vulnerable group, brought about by the one-child policy, in August 2007 the Chinese government introduced a relief policy for them.Citation35 The policy was first tried in ten pilot places and then extended to the whole of China. It is a good beginning. However, there are very rigid age criteria for identifying families who are eligible for these subsidies, for example, only mothers aged 49 or older in the families with a deceased or disabled only child are eligible,Footnote* and their entitlement to the subsidy will be suspended if they adopt or give birth to another child. In addition, the amount of the subsidy was quite low, only 100 RMB (US$ 16.40) per person per month for a shidu family. The amount has been increased to 135 RMB (US$ 22) per month since 2012.

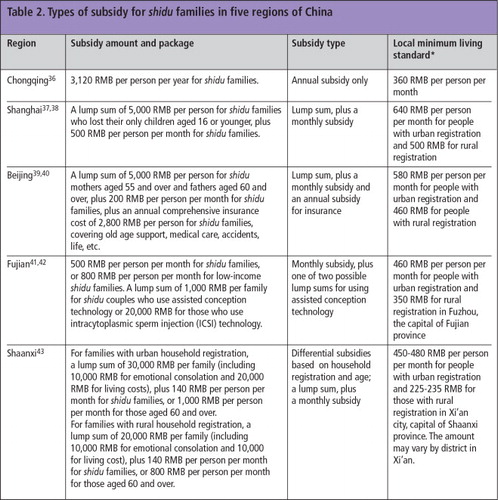

According to the China Population and Family Planning Law (2002), it is a local government obligation to provide support and subsidies to shidu families.Footnote† Because the main source of the subsidy is the regional governments, the amounts and packages provided vary by region. Basically, there are five types of subsidy package, exemplified by three municipalities including Chongqing, Shanghai, Beijing, and two provinces, including Fujian and Shaanxi, as outlined in Table 2.

Table 2 Types of subsidy for shidu families in five regions of ChinaCitation36–43Data sources: Relevant policy documents issued by the municipal and provincial governments.Footnote*

As the table shows, the subsidies in all five regions are lower than or close to the local minimum living standard. Hence, unless the shidu families have other sources of income, such as a pension or old age insurance, this financial aid does little to improve their economic situation. Furthermore, in some regions there is an urban–rural gap in the amount of subsidy. For example, in Shaanxi province, there is a 10,000 RMB difference in the lump sum for those with urban versus rural household registration. The official explanation for this gap is the difference in living cost between the cities and the countryside. Yet, people in the cities are more likely to have pensions. According to one survey, two-thirds of the elderly in the cities have pensions while only 4.6% in the countryside do.Citation2

Policy implications and recommendations

The number of shidu families in China has been increasing rapidly every year and will reach a peak in the near future. A research study has estimated that nearly 10 million out of 200 million only children born between 1975 and 2010 would die before the age of 25 years.Citation9 With more and more shidu parents getting old, their elderly care has become an urgent issue for China. The Chinese government realized this and has introduced some policies to improve their situation. However, there is still a long way to go.

The differential between urban and rural China is a particularly important issue. Shidu parents in rural China get much less help and support than their urban counterparts. They have neither pensions nor access to other governmental resources and have received less attention from both the state and the society.

I believe the fundamental solution to elderly care for shidu parents is substantial reform of the one-child policy, with a policy that both avoids unsustainable population growth and relieves the serious ageing problem in China. This is unlikely in the foreseeable future. Within the framework of the current one-child policy and existing elderly care laws and policies in China, I believe shidu families should receive increased economic and emotional support, and efforts made to eliminate discrimination against them.

In addition, the urban–rural differences in lump sum payments and subsidies should not continue. Although living costs are higher in the cities, the families in the countryside usually have lower or no pension. The government should provide shidu families with rural household registration with the same subsidies as those with urban registration, if not higher.

The government should also provide appropriate elderly care for shidu families in different situations. For those who are financially secure, the local government or local community should act as a guarantor for them if they seek admission to a senior care home, or neighbourhood community elderly care programmes should be developed so that shidu families can stay at home and still be entitled to state-organised elderly care. For those with economic constraints, the government should provide them with free or subsidised elderly care. For those in the countryside, the government should not only provide economic relief but also free elderly care in the rural areas. More state investments should be made into the establishment of elderly care facilities and the training of professional elderly caregivers, so that there will be adequate elderly care resources to serve all elderly people.

For those who want to have another child, the government should provide help instead of reducing their relief. It should provide those who are able to have another biological child with financial and clinical support. For those who are willing to adopt a child, the government should simplify the adoption procedures and waive the adoption fees.

Further comparative, nationally representative data are needed, particularly from the countryside, to better inform policies. China’s one-child policy has created the largest number of shidu families in the world. Its unique urban–rural household registration system makes the subject of elderly care, including for shidu families in China, an issue that needs sophisticated study.

On 26 December 2013, the Chinese government issued a new policy on relief for shidu families.Citation44 The monthly subsidy was increased to 340 RMB per person per month (US$ 56) for those with urban household registration and 170 RMB per person per month (US$ 28) for those with rural household registration, in recognition of the challenges facing the shidu families. Under this new policy, the government will also provide subsidies for insurances and put those who are aged 60 and over and also disabled members of shidu families into state-sponsored senior homes; and the richer regions will provide elderly care subsidy to the disabled and economically constrained elders in shidu families. Although it will take some time to turn these guidelines into implementable measures, it is a good sign that China is addressing the elderly care of shidu families in an active way.

Notes

* The one-child policy was launched with the “Open letter to all the members of the Communist Party and the Communist Youth League regarding the family planning issue in China”, issued by the Chinese Government, 25 September 1980.

† Shidu is the transliteration of the Chinese words ![]() (losing an only child).

(losing an only child).

* The terms “shidu families” and “shidu parents” are used interchangeably here. Since all the relevant policies in China target families, the term “shidu families” will be used most of the time, except when parents are particularly referred to.

† In some parts of China, a couple with rural household registration are allowed to have another child if the first child is a girl; in some ethnic minority regions, a couple can have more than two children.

** Mentioned in: Resolutions on Deepening the Reforms on Several Major Issues, released by the Chinese government, 15 November 2013.

* See the 1980 Open Letter. But the Letter did not mention the risks of parents losing their only children.

† China’s household registration system, introduced in early 1950s and still in force today, divides its citizens into those with urban household registration and those with rural household registration. The former were entitled to jobs, free or cheap housing and medical care, and better education, while the latter had nothing except free house sites and user rights to farm land which was collectively owned by the villages. Apart from joining the army or going to college, rural people were not allowed to migrate to the cities of their own free will and had very few opportunities to obtain urban registration. Although rural people are allowed to migrate to cities without changing their rural household registration as part of China’s urbanization, people with rural household registration are not entitled to the same welfare package as their urban counterparts. Since very recently, in some provinces, farmers whose land is expropriated by the state are also eligible for the urban pension, a new policy practised in very few parts of China at this writing.

* I am not aware of comparative data for non-shidu elderly. However, to my knowledge, the large proportion of shidu elderly in such difficulties cannot be imagined among non-shidu elderly.

* A few regions have more rigid criteria.For example, in Shanghai the policy stipulates that eligible families include only those whose only child died before the age of 16 years. See: http://www.shanghai.gov.cn/shanghai/node2314/node3124/node3134/node3136/u6ai1599.html

† The law stipulates that local governments should provide necessary help to parents whose only child is deceased or disabled, who are not going to give birth to or adopt another child.

References

- Zhang Ran. The National Health and Family Planning Commission of China has proposed improved birth policies. Beijing Times. 12 November 2013.

- Wu Yushao, Dang Junwu. China Report on the Development of Ageing Cause (2013). Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press. 2013.

- China Ministry of Health. 2010 China Yearbook of Health. 2010; Beijing Union Medical College Press: Beijing.

- Wei Zhou, Hong Mi. Estimation of number of the Shidu families in China and discussion of relief standards. China Population Science. 5: 2013; 2–9.

- Yongcai Xie, Wanding Huang, Maofu Wang. Research on the social assistance system of the shidu group: a perspective of sustainable livelihoods. Social Security Studies. 17(1): 2013; 72–79.

- Wu Jiaxiang. China shidu elderly. Southern People Weekly. 25 July 2012.

- Li Yan. Pain of the shidu people. Southern Metropolis Weekly. 17 July 2012.

- Yafu He. The Incontrollable Population Control. 2013; China Development Press: Beijing.

- Fuxian Yi. Big Country with An Empty Nest: Reflections on China’s Family Planning Policy. 2013; China Development Press: Beijing.

- China Ministry of Labour and Social Security. Announcement on preventing and correction of earlier retirement of enterprise workers against state rules. 9 March 1999. http://www.molss.gov.cn/gb/ywzn/2006-02/16/content_106842.htm

- Yuhua Guo, Aishu Chang. Life cycle and social security: a sociological exploration of the life course of laid-off workers. Social Science in China. 1: 2006; 19–33.

- Bichun Zhang, Lihua Jiang. Triple difficulties and support system of the shidu parents. Population and Economics. 194(5): 2012; 22–31.

- Li Tangning. One-hundred RMB old age insurance can not meet the needs for rural elderly care. Economic Information Daily. 15 November 2013.

- China Ministry of Health. 2012 China Yearbook of Health. August. 2012; Beijing Union Medical College Press: Beijing.

- It is not easy to live, we cannot even afford to die? Accessed on 25 April 2014. http://gongyi.people.com.cn/BIG5/191247/218226/index.html

- Chao Zhao, Xiaojie Yu. China becomes the only country with over 100 million aged population, facing the challenges of an ageing society. 24 August 2011. http://news.xinhuanet.com/2011-08/24/c_131071747_2.htm

- Guangzhong Mu. China’s institutional elderly care development: difficulties and solutions. Journal of Huazhong Normal University (Humanities and Social Sciences). 51(2): 2012; 31–38.

- How are we supposed to support our old age in the future? The Beijing News. 31 March 2012.

- Shiying Wu, Jian Zhou. Difficulties facing the death of the only children. Journal of Changchun University of Science and Technology (Social Sciences Edition). 26(3): 2013; 79–81.

- Yana Liu. Impoverishment of the shidu people in China and construction of their aid system. Social Science Journal. 208(5): 2013; 46–50.

- Zhang Li, Zhou Zhou. The number of shidu families has been over 1 million. The sadness destroyed the parents physically and mentally. Zhejiang Daily. 26 July 2012.

- Jun Liao, Yingxun Zhou, Xiaoying Wu. Having no one to rely on when getting old? Approaching the Shidu families in China. China Comment. 13: 2012; 56–59.

- Li Yan. A monologue of a shidu mother. Southern Metropolis Weekly. 17 July 2012.

- Zhao Lina, Li Lixin. Two bets of a shidu elderly. Science Life Weekly. 12 August 2012.

- Li Jiawei. Di’s mother: a shidu person. China Weekly. 6 September 2012.

- Yan Zhou, Qiang Pan. Research claims family planning has decreased China’s population by 400 million, the number of the shidu families is increasing. 13 October 2013. http://politics.people.com.cn/n/2013/1013/c70731-23185494.html

- Shuai Zhang, Peng Yu. Shidu mothers’ Tomb Sweeping Day: life monologue of a special group. 3 April 2013. http://news.iqilu.com/shandong/yuanchuang/2013/0403/1492099.shtml

- Zhu Chunxian. Life of a shidu person: her son was murdered and she got no compensation before she died. Law Weekly. 5 January 2013.

- Qin Zhenzi. A birth control office director’s pain to lose her only child. China Youth Daily. 8 August 2012.

- Chen Qiao. Beijing’s shidu elderly people are included in the governmental social security and have a hope to gain special relief. Beijing Times. 17 October 2013.

- Xiaoqing He. Hard way to new birth: a record of the new births of families losing their children in the Wenchuan earthquake. Beijing Literature. 5: 2013; 4–23.

- Bichun Zhang, Weidong Chen. Transition and adaptation: the logic for maintaining the stability of the shidu family. Journal of Huangzhong Normal University (Humanities and Social Sciences Edition). 52(3): 2013; 19–26.

- Changchun Women’s Federation Survey Report: shidu families need help to overcome their difficulties. China Women News. 19 August 2013.

- Qile Zhang. The state’s protection of shidu people’s rights. Modern Law Science. 35(3): 2013; 11–17.

- National Population and Family Planning Commission (dissolved March 2013, its family planning function merged into the National Health and Family Planning Commission of China) and Ministry of Finance, China. Pilot Plan for the Relief System for the Families with a Deceased or Handicapped Only Child; 31 August 2007. http://www.nhfpc.gov.cn/zhuzhan/jsbmg/201305/9cc5459a79db40bfb48df6618be985a8.shtml

- Wei Zhu, Yang Shen. Many places in China have issued policies to help shidu families. 10 September 2012. http://news.xinhuanet.com/2012-09/10/c_113022924.htm

- Shanghai Municipal People’s Government. Shanghai’s Regulations on the Family Planning Awards and Subsidies. 1 June 2011. http://www.shanghai.gov.cn/shanghai/node2314/node3124/node3134/node3136/u6ai1599.html

- Cheng Xianshu. Shanghai’s shidu subsidy will increase from 150 RMB per month per person to 500 RMB. 23 September 2013. Shanghai Evening Post.

- Wang Xiaohui. Pain of shidu families. China Times. 27 November 2013.

- Liu Huan. Shidu families who will get comprehensive insurance. Beijing Daily. 5 July 2012.

- Fujian Population and Family Planning Commission Fujian Agriculture Office Fujian Department of Education and et al. Opinions on improving the help to family planning affected families. May 2013. http://www.fujian.gov.cn/zwgk/zxwj/szfwj/201307/t20130703_606403.htm

- Zhong Zhiwei. Shidu families in Fujian will get reproductive subsidy. People’s Daily. 5 July 2013.

- Shaanxi Population and Family Planning Commission, Shaanxi Department of Finance. Opinions on establishing improved support and relief system for the elderly care of shidu families. September 2012. http://www.shaanxi.gov.cn/0/104/9441.htm

- The National Health and Family Planning Commission of China China Ministry of Civil Affairs China Ministry of Finance China Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security and China Ministry of Housing and Urban–Rural Development. Announcement on further implementation of aid and support for the needy families affected by family planning policies. 26 December 2013. http://www.nhfpc.gov.cn/jtfzs/s3581/201312/206b8b4e214e4a5ea2016417843d7500.shtml