Abstract

Abstract

The greatest challenge today is to meet the needs of current and future generations, of a large and growing world population, without imposing catastrophic pressures on the natural environment. Meeting this challenge depends on decisive policy changes in three areas: more inclusive economic growth, greener economic growth, and population policies. This article focuses on efforts to address and harness demographic changes for sustainable development, which are largely outside the purview of the current debate. Efforts to this end must be based on the recognition that demographic changes are the cumulative result of individual choices and opportunities, and that demographic changes are best addressed through policies that enlarge these choices and opportunities, with a focus on ensuring unrestricted and universal access to sexual and reproductive health information and services, empowering women to fully participate in social, economic and political life, and investing in the education of the younger generation beyond the primary level. The article provides a strong argument for why the Programme of Action that was agreed at the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) 20 years ago continues to hold important implications and lessons for the formulation of the post-2015 development agenda, which is expected to supersede the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).

Résumé

Le principal enjeu aujourd’hui est de répondre aux besoins des générations actuelles et futures, d’une population mondiale importante et qui s’accroît, sans imposer de pressions catastrophiques sur l’environnement naturel. Relever ce défi dépend de changements politiques décisifs dans trois domaines : une croissance économique plus intégratrice, une croissance économique plus écologique et des politiques démographiques. Cet article se centre sur les activités destinées à traiter et exploiter les changements démographiques pour le développement durable, qui sont largement en dehors du cadre des débats actuels. Les activités dans ce sens doivent être fondées sur le constat que les changements démographiques sont le résultat cumulé de possibilités et choix individuels, et que les changements démographiques sont traités au mieux par des politiques qui élargissent ces choix et possibilités. Il s’agit en particulier de garantir un accès universel et sans restriction à l’information et aux services de santé sexuelle et génésique, doter les femmes des moyens de participer pleinement à la vie sociale, économique et politique, et investir en faveur de l’éducation de la jeune génération au-delà du niveau primaire. L’article donne un argument solide montrant pourquoi le Programme d’action adopté à la Conférence internationale sur la population et le développement il y a 20 ans contient toujours des incidences et leçons importantes pour la formulation du programme de développement de l’après-2015, qui devrait se substituer aux objectifs du Millénaire pour le développement (OMD).

Resumen

El mayor reto hoy en día es satisfacer las necesidades de generaciones actuales y futuras, de una amplia población mundial creciente, sin imponer presiones catastróficas en el medio ambiente natural. Para enfrentar este reto se necesitan cambios decisivos de políticas en tres áreas: crecimiento económico más inclusivo, crecimiento económico más verde y políticas de población. Este artículo se enfoca en los esfuerzos por abordar y aprovechar los cambios demográficos para el desarrollo sostenible, que en su mayoría quedan fuera del alcance del debate actual. Con este fin, los esfuerzos deben basarse en el reconocimiento de que los cambios demográficos son el resultado acumulativo de opciones y oportunidades individuales, y que la mejor manera de abordar los cambios demográficos es por medio de políticas que amplíen esas opciones y oportunidades, con un enfoque en asegurar acceso no restringido y universal a información y servicios de salud sexual y reproductiva, empoderando a las mujeres a participar al máximo en la vida social, económica y política, e invirtiendo en la educación de la generación más joven más allá del nivel primario. El artículo plantea un sólido argumento para explicar por qué el Programa de Acción acordado hace 20 años en la Conferencia Internacional sobre la Población y el Desarrollo (CIPD) continúa teniendo importantes implicaciones y lecciones para la formulación de la agenda de desarrollo post 2015, que se espera que reemplace los Objetivos de Desarrollo del Milenio (ODM).

Today, mega population trends at the national and global levels – continued rapid population growth, population ageing, urbanization and migration – constitute important developmental challenges and opportunities in themselves. Furthermore, they influence the concerns and objectives that are at the top of international and national development agendas. Population dynamics affect economic development, employment, income distribution, poverty, social protection and pensions; they affect efforts to ensure universal access to health, education, housing, sanitation, water, food and energy; and they also influence the sustainability of cities and rural areas, environmental conditions and climate change.

Against this background, population dynamics have moved to the fore in the national and international discussions on development and sustainable development goals and targets. The importance of population dynamics was emphasized in the outcome document of the Rio+20 conferences The Future We Want Citation1 and in the report of United Nations (UN) Task Team on the post-2015 development agenda Realizing the Future We Want for All.Citation2 Building on these developments, the United Nations Development Group (UNDG) has initiated a global thematic consultation on population dynamics and the post-2015 development agenda. But how exactly are population dynamics linked to sustainable development, and how can population dynamics be shaped to ensure more sustainable development pathways?

The discussion on the linkages between population dynamics – in particular population growth – and its environmental implications is often characterized by gross simplifications. Indeed, the poorest countries which have the highest population growth have thus far contributed least to global greenhouse gas emissions. But it would be hasty to conclude that population growth does not have important implications for environmental sustainability. Likewise, it would be inaccurate to suggest that population growth has a clear and direct impact on the natural environment. The relationship between demographic change and environmental sustainability is complex and mitigated through many different factors.

This article discusses the links between sustainable development and demographic change, and policies for more sustainable development. It argues that the objective of sustainable development demands a focus on three principle policy levers, notably policies that promote more inclusive economies, policies that ensure greener economies and policies that address and harness population dynamics. While the article outlines the importance of more inclusive and greener economies, it focuses its discussions on the need to plan for and shape population dynamics. This focus is not meant to suggest that the achievement of more equal and greener economies is easy or straightforward, rather it is motivated by the fact that policies to address and harness population dynamics are generally neglected. Despite the growing realization that demography matters for sustainable development, many continue to treat demography as though it was destiny. It is not. This article takes issue with the view that demographic change is exogenously determined and cannot be influenced by policies, as well as the view that demographic change can only be influenced through population control policies that violate human rights. The Programme of Action (PoA) that was agreed at the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) 20 years ago not only highlighted the importance of population dynamics for sustainable development, but also spelled out in great detail how to shape population dynamics through rights-based and gender-responsive policies. The ICPD Programme of ActionCitation3 holds important implications and lessons for the formulation of the post-2015 development agenda.

“The 1994 Conference was explicitly given a broader mandate on development issues than previous population conferences, reflecting the growing awareness that population, poverty, patterns of production and consumption and the environment are so closely interconnected that none of them can be considered in isolation.” (ICPD PoA, 1994, Preamble 1.5)

Sustainable development and population dynamics

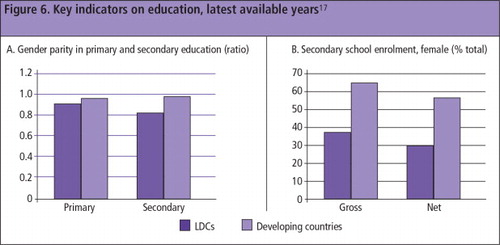

According to the latest UN population projections, the world population stands at about 7.2 billion in 2014, and will continue to grow for decades to come. Between now and 2050, the world population will grow by another 2.4 billion people – about as many people as inhabited the planet in 1950. Compared with previous population projections, the most recent projections, revised in 2012, suggest a more rapid increase in the world population (). This is largely due to stalled fertility decline in high fertility countries in Africa, a slightly higher fertility in very populous countries in Asia, and slight improvements in life expectancy at birth.Citation4

Figure 1. World population: 1950–2100.Citation4

The global trends mask considerable differences between countries, however. While fertility and population growth are still high in the poorest countries, fertility and population growth have fallen in many other countries. Indeed, an increasing group of developed countries have fertility levels below replacement level, and therefore are already or will be witnessing a population decline. Because of growing demographic differences between countries, many countries today have very different concerns. Countries that have a low and falling fertility, may find it difficult to understand concerns about high fertility and population growth elsewhere. But even though the demographic realities differ considerably at the national level, these demographic realities have global implications. Global climate will change regardless of where greenhouse gases are emitted, and global population will grow regardless of where this growth originates. Although the least developed countries have contributed least to global greenhouse gas emissions, they feel the effects of global warming caused by the advanced countries. Likewise, while the advanced countries have comparatively low fertility levels today, they will feel the effects of global population growth which originate largely in the poorest countries. For example, efforts to meet a rapidly growing demand for water, food and energy will affect all countries, and so will the failure to meet these growing demands.

“Demographic factors, combined with poverty and lack of access to resources in some areas, and excessive consumption and wasteful production patterns in others, cause or exacerbate problems of environmental degradation and resource depletion and thus inhibit sustainable development.” (ICPD PoA, 1994, Ch. 3.25)

To meet the needs of the people who currently inhabit the planet, especially the poor, as well as the needs of those who will be added to the planet, is today’s great developmental challenge. How these efforts will affect the natural environment depends on several mitigating factors. It depends not only on how many people are living on the planet, but what living standards they have, how the available economic resources are distributed, and how goods and services are produced. This article argues that meeting this challenge demands a more balanced distribution of economic resources, especially as inequalities and inequities are continuing to increase, higher and more sustained output growth, as well as policies to address the challenge of population dynamics, and harness their opportunities for sustainable development.

The challenge of poverty reduction and economic growth

Globally, about 1 out of 6 persons continues to live in extreme poverty with less than US$ 1.25 per day in purchasing power parities.Citation5 A reduction in poverty can be achieved in only one of two principle ways: through productive and remunerative employment, or through transfers. Remunerative employment and cash transfers will ensure that people have an adequate income to purchase essential goods and services, whereas in-kind transfers will ensure that people can consume essential goods and services even without an adequate income. However, fundamentally, poverty reduction, which depends on the enjoyment of essential goods and services, is not possible without economic growth.

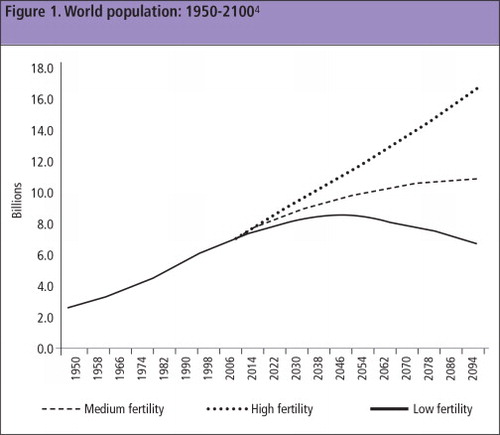

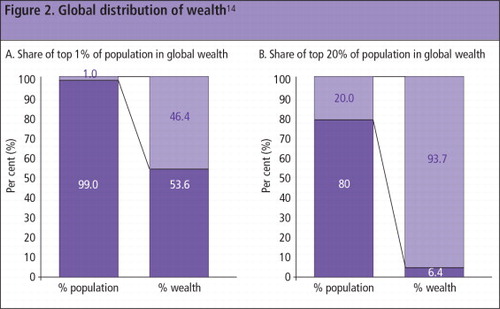

Economic growth is a necessary condition, albeit not a sufficient condition, to combat poverty. Without economic growth, countries will not be able to meet the growing demand for goods and services, create full employment, raise household incomes or finance public transfers. But even with economic growth, many countries have not been able to ensure basic access to essential goods and services, create full, productive and remunerative jobs, raise household incomes, and fight poverty. Indeed, in many countries, economic growth has been associated with a considerable rise in inequalities. On average, the returns to capital have increased at a higher rate than the returns to labor.Citation6–10 In several countries, workers have seen a decrease in unit labor costs, and in some they have witnessed a decline in wages which has been associated with an increase in working poor.Citation11–13 Imbalances with respect to income distribution have also further exacerbated imbalances with respect to wealth ( and 3).

Figure 2. Global distribution of wealth.Citation14

Figure 3. Global distribution of income.Citation15

In a world characterized by rising inequalities, a more balanced distribution of economic resources is a human and economic imperative. The redistribution of resources through transfers and taxes can contribute to a considerable fall in inequalities. According to the latest data by the OECD, the Gini Coefficient after transfers and taxes was 32%, down from 46% before transfer and taxes, for the OECD countries, on average. However, there are limits to the redistribution of resources. What may be an acceptable social consensus as regards resource distribution in the social-market economies of Europe would not be a consensus in the USA. Furthermore, despite considerable redistributive measures, some countries have achieved only a small reduction in inequality – Brazil,Footnote* for example – and the majority of countries have even witnessed a continuing rise in inequalities.

In addition to political and social constraints, many of the poorest countries confront economic constraints to redistribution. In 2012, the income of low-income countries amounted to about US$ 1.20 per person per day, measured in 2005 US dollars. Adjusted for purchasing power parities, the population would have had about three times as much. In other words, even if the poorest countries evenly distributed their entire resources, it would not be sufficient to ensure a decent life for all. A radical redistribution of global resources amongst the world population, however, would significantly increase the income of developing countries – the income of low-income countries would increase by about 18 times and that of middle-income countries by about three times – but it would significantly reduce the living standards in the developed countries. The average person in the developed countries would need to make ends meet with less than a quarter of the resources that they currently have. Even if a radical redistribution of resources at the national, regional or global level were possible and desirable, it could never be a viable way to sustainable poverty reduction.

In 2012 real output per capita in the least developed countries stood at about US$ 518 per annum, which is about one-third of the estimated real output per capita of the USA in 1800. If economic output did not grow between now and 2030, and if populations grew at the rate suggested by the medium variant of the UN population projection, the real per capita output in the world’s least developed countries would shrink by no less than 32% over current levels, owing to high population growth, and real per capita output in the USA would shrink by about 13%. At the global level, by 2030 output per person – not taking into consideration the depreciation of capital – would be about 16% lower than today.Footnote†

Inequalities are self-perpetuating, and once they are established, they are very hard to eliminate. Social transfers can help to prevent suffering of the poor, and they can help to slow the increase in inequalities, but social transfers are rarely enough to ensure a decrease in inequalities. The most effective way to counteract rising inequalities is through inclusive economic growth, which creates full, productive and remunerative employment opportunities, and through complementary labor market regulations, which prevent working poverty. Furthermore, redistributive measures alone will not suffice to meet the growing needs of people; higher economic output is required. For example, today food security is still largely a question of distribution and access – the ability of households to go to a market and purchase the food they need – but food security is rapidly becoming a question of availability – the capacity of the world economy to produce sufficient food to feed a growing world population. In other words, while a better distribution of food could theoretically prevent people from going to bed hungry today, sustainably combating hunger will depend on a much higher level of agricultural output. To feed a world population of nine billion will require that agricultural output increases by about 70% over current levels, according to Food & Agriculture Organization estimates.Citation19 But more people will not only need more food, they will need more of everything.

The challenge of economic growth and environmental sustainability

The production of all goods and services depends on the transformation of natural resources, which inevitably places pressures on the natural environment. Despite clear evidence that climate change is due to human activity,Citation20 countries have thus far failed to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. By contrast, despite a general increase in energy efficiency – measured as the energy use per unit of output – countries have seen a rapid increase in energy use. In 1934 the original Beetle built by Volkswagen had a fuel consumption of about 22 MPG, and in 2014 Volkswagen still sells a Beetle that has a fuel consumption of 23 MPG. As the efficiency gains were eaten up by greater weight, faster acceleration, higher speed and better safety features, so were the potential environmental benefits.Citation21 Generally, the increase in resource efficiency was insufficient to compensate for the overall increase in output, and was therefore associated with a continuing increase in greenhouse gas emissions ().Footnote**

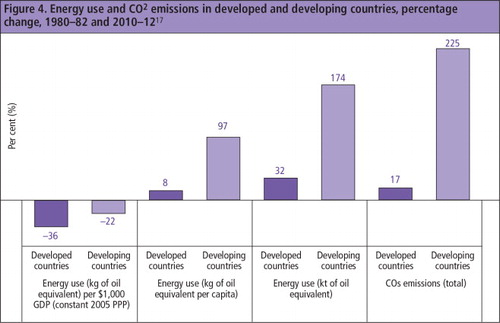

Figure 4. Energy use and CO2 emissions in developed and developing countries, percentage change, 1980–82 and 2010–12.Citation17

While the energy consumption per person in developing countries is only about 76% lower than in the developed countries, the total energy consumption in developing countries is 24% higher than that of the developed countries. But within the group of developing countries, there are marked differences between the low-income and middle-income countries. The low-income countries have by far the lowest energy consumption, per capita and in absolute terms, but even the low-income countries have rapidly increasing energy consumption. Between 1980–1982 and 2010–2012, the total energy consumption of low-income countries increased about twice as fast as that of the developed countries, and the energy consumption of middle-income countries increased about six times as fast.

A continued rise in fuel prices will gradually encourage a shift away from carbon-intensive production and consumption, but there is a considerable risk that this shift will come too late to avert irreparable damage to the natural environment and major natural catastrophes. The principle of precaution therefore demands that governments actively promote this shift through a combination of incentives, disincentives and prohibitions. This will require a mix of economic instruments, notably fiscal policies and functioning emissions markets, and legal instruments, including environmental legislation and product standards.Footnote* However, so far countries have evidently made little progress in reducing energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions, which may be attributable to imbalances in bargaining power. Those industries that benefit from the status quo (“brown economy”) typically have a stronger position and voice than those that would benefit from change (“green economy”). Furthermore, those who derive benefits from unsuitable and unsustainable practices are often not the same ones that bear the cost of these practices. It is often the poorest countries who suffer most from natural disasters induced by climate change, and even in advanced countries, it is the poorest people who are often most exposed to the health hazards of environmental pollution.

Solutions are complicated by the fact that many natural resources do not have an owner who can charge for the use of those resources, effectively promoting the internalization of externalities, and encouraging a more sustainable consumption of the resource in question. Theoretically, this challenge could be solved by turning natural resources into private goods, as argued by Coase,Citation32 but it may arguably be more reasonable to turn them into public goods. Where environmental resources and their damages are confined to the local or national level, a government can be an effective custodian, but where environmental resources or their damages have transnational or global implications no government can assume this role alone.Footnote*

One country alone may be able to address the contamination of a local lake; several countries together may be able to address the pollution of a river system; but all countries together will need to address the problem of climate change. This includes, on the one side, global efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and, on the other, global efforts to maintain or increase the planet’s capacities to sequester emissions. Addressing these challenges is a common, albeit differentiated responsibility, which depends on global governance. Such governance structures will be needed to set limits on greenhouse gas emissions, protect natural resources for sequestration, define financial responsibilities of partner countries, and establish mechanisms for technology transfer. However, efforts to mitigate environmental damage through sustainable consumption and production would be incomplete and ineffective without concomitant efforts to promote more equitable societies and shape population dynamics.

The fact that countries with the highest rates of population growth are by and large the countries that have had the lowest levels of greenhouse gas emissions has often been misinterpreted. Population growth can have effects on the climate, even if it has not had it so far, and population dynamics more generally can also have impacts on other natural resources. Population growth may not matter so much as long as a large share of the population lives in extreme poverty, characterized by a minimal level of consumption, but population growth starts mattering much more as a growing share of the population escapes poverty. The legitimate ambition of the least developed countries to raise the living standards of their populations will thus have far-reaching implications for the environment.

Today, many natural hazards – shifts in precipitation and an increase in desertification, with negative implications for agriculture – are most frequent and intense in the least developed countries.Citation34 But the pressures on forests, land and water in the least developed countries are not only attributable to greenhouse gas emissions and climate change caused elsewhere; they are also exacerbated by the patterns of production and consumption at home. Many of these countries rely heavily on the exploitation of their natural resources to spur economic growth – notably extractive industries, agriculture, fisheries and timber production – and many of the poorest households also rely heavily on wood and other natural resources for their daily needs. The world’s least developed countries are suffering most from a rapid degradation and depletion of their natural resources, and this is effectively undermining a sustainable catch-up with more advanced countries.Citation35

“[…] Slower population growth has in many countries bought more time to adjust to future population increases. This has increased those countries’ ability to attack poverty, protect and repair the environment, and build the base for future sustainable development… Stabilization levels of fertility can have a considerable positive impact on quality of life.” (ICPD PoA, 1994, Ch. 3.14)

As discussed above, without a higher rate of economic growth it will not be possible to maintain or raise living standards of growing populations; yet without a fundamental change in the developmental model, it will not be possible to halt or reverse the unsustainable destruction of the natural environment. While population growth poses challenges, especially without essential changes in the patterns of consumption and production, population dynamics also provide opportunities. A fall in fertility levels and slower population growth can enable countries to reap a demographic dividend resulting from demographic transitions and jumpstart economic development.

Migration can also be an important enabler of social and economic development, which can allow people to respond to changes in social, economic and environmental conditions. And through integrated rural-urban planning and by strengthening urban-rural linkages, rural and urban transformation can be a powerful driver of sustainable development. However, realizing the potential benefits of these changes in the size, age structure or geographic distribution of populations depends on supportive policies.Citation36

“Poverty is also closely related to inappropriate spatial distribution of population, to unsustainable use and inequitable distribution of such natural resources as land and water, and to serious environmental degradation.” (ICPD PoA, 1994, Ch. 3.14)

Unplanned urban growth increases vulnerability to natural hazards and can exacerbate urban poverty. Despite increasing attention to improving access to basic services in slums, in absolute terms the number of slum dwellers in the developing world has risen as urban municipalities have failed to keep up with the rapid pace of generation of new slum areas. Today, many cities are simultaneously dealing with congestion and sprawl. However, the unfolding challenges in many countries, especially the least developed, can be avoided. Indeed, by anticipating urbanization, leveraging the advantages of agglomeration, and managing urban growth as part of their respective development strategies, central governments and local authorities can address the challenges of urban growth and turn urban growth into a driving force for more sustainable development. In urban areas, governments can provide essential goods and services at lower costs per person than in rural areas, and in urban areas the population has lower energy consumption, adjusted for income levels, than the population in rural areas. The opportunities for energy saving are particularly significant in the housing and transport sectors. To address the challenge of high population density with deteriorating living conditions, especially in slums, as well as the challenge of urban sprawl, critically depends on infrastructure development, transport hubs, and green spaces.Citation36

“Macroeconomic and sectoral policies have, however, rarely given due attention to population considerations. Explicitly integrating population into economic and development strategies will both speed up the pace of sustainable development and poverty alleviation and contribute to the achievement of population objectives and an improved quality of life of the population.” (ICPD PoA, 1994, Ch. 3.3)

Population dynamics and its determinants

Accepting persisting poverty levels is as unacceptable as accepting continued environmental degradation. Either would result in human harm, humanitarian crises, civil strife and conflict. How can the world community meet the dual objective of raising living standards and protecting the environment? The Earth Summit in 1992 in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, outlined a two-pronged approach: a shift towards sustainable consumption and production, and policies to address demographic change.Citation37 Echoing this call the ICPD Programme of Action stated:

“Sustainable development as a means to ensure human well-being equitably shared by all people today and in the future, requires that the interrelationships between population, resources, the environment and development should be fully recognized, appropriately managed and brought into harmonious, dynamic balance. To achieve sustainable development and a higher quality of life for all people, States should reduce and eliminate unsustainable patterns of production and consumption and promote appropriate policies, including population related policies, in order to meet the needs of current generations without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” (ICPD PoA, 1994, Ch. 2.6)

Sustainable consumption must ensure a more conscientious consumer behavior and a more balanced distribution of resources; sustainable production needs to ensure greater resource efficiency and a greater reliance on renewable energy; and population policies must ensure health, education and the realization of fundamental human tights. To discuss the entire range of policies that are needed to promote sustainable development – including policies to promote more equitable and greener economies – would go well beyond the scope of any article. The following secs will therefore concentrate on efforts to address and harness population dynamics, which remain neglected in the discussion on sustainable development.

The imperative of sexual and reproductive health and rights

Future demographic trends critically depend on today’s policies. For the world population to reach 9.6 billion around 2050 and stabilize around 10.9 billion by 2100 – as suggested by the medium-variant of the UN population projection – average world fertility must reach replacement level by 2035–40 and remain below replacement level for the rest of the century. Projections show that small differences in fertility levels can add up to big differences in population trajectories. If each woman had on average half a child more than assumed by this medium variant, the world population would grow to about 11 billion by 2050 and nearly 17 billion by 2100. If, on the other hand, each woman had on average half a child less than assumed by the medium variant, the world population would grow to about 8 billion by 2050 and fall to 7 billion by the end of the century.Citation4 Footnote* In short, every decade of delay in reaching replacement level fertility implies continued, significant population growth for decades to come.

The countries which today have the highest fertility and population growth – mostly the countries in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia – generally also have “major concerns” about high fertility and population growth. According to the latest survey of the UN Population Division, more than 70% of the least developed countries’ governments have major concerns as regards high fertility and population growth. Furthermore, more than 70% of their governments have major concerns as regards rapid urban population growth.Citation38 Responding to global and national concerns about high fertility and population growth, the Sustainable Development Solutions Network has, in its most recent proposal on sustainable development goals, put forward a target to reduce fertility levels everywhere to replacement level. The network of academics that stands behind this proposal, however, makes it clear that efforts to this end shall not violate fundamental human rights and freedoms.Citation39

Indeed, the fact that population growth can pose challenges to sustainable development neither suggests nor necessitates any type of coercive population control. The analysis of the population-environment linkages is one thing; recommendations about appropriate policy responses are another entirely. Policies to address and harness population dynamics – be they focused on addressing population growth or decline, or on migration and urbanization – must respect fundamental human rights and freedoms. Together, the Beijing Platform of Action and the ICPD Programme of Action outline essential rights-based and gender-responsive policies to address population dynamics.

“The present Programme of Action recommends to the international community a set of important population and development objectives: …sustained economic growth in the context of sustainable development; education, especially for girls; gender equity and equality; infant, child and maternal mortality reduction; and the provision of universal access to reproductive health services, including family planning and sexual health.” (ICPD PoA, 1994, Preamble 1.12)

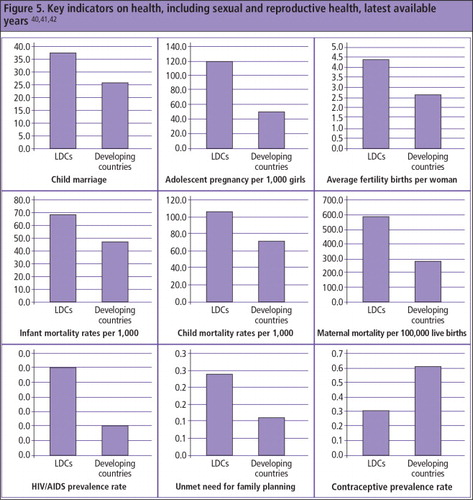

While many countries have made progress towards many of the development goals and targets outlined in the Millennium Development Declaration, important challenges remain. Progress in reducing maternal mortality, which critically depends on access to sexual and reproductive health care, was particularly weak.Citation5 The challenges are greatest in the poorest countries. To date, the average least developed country has a significantly higher share of child brides, adolescent pregnancies, infant, child and maternal mortality, and people living with HIV and AIDS than the average developing country (). These indicators are closely linked to an unmet need for family planning, low contraceptive prevalence rates and illegal, unsafe abortion.

Figure 5. Key indicators on health, including sexual and reproductive health, latest available years.Citation40–42

Globally, today about 222 million women continue to lack access to modern methods of family planning.Citation43 In the least developed countries it is estimated that the unmet need for family planning is 24%, which compares with 11% in developing countries as a group. However, even within the least developed countries, differences are large. Data from Demographic and Health Surveys undertaken in 1998 and again in 2008 in a total of 17 African least developed countries (LDCs) show that women with a secondary or higher education, women in urban areas, and women from the wealthiest households are less likely to become mothers as adolescents, more likely to use contraceptives and less likely to have an unmet need for contraception than women with no or primary education, women in rural areas, or women of poor households.Citation40,44

The realization of fundamental human rights, including sexual and reproductive health and rights, enlarges the opportunities and choices of individuals. It is unacceptable that children are married off, and that teenagers become mothers and fathers because they are not allowed to access sexual and reproductive health information and services. Whether, when and whom to marry, and whether, when and how many children to have are some of the most far-reaching decisions in anybody’s life. Why should the right to take this decision be denied to adolescents, and especially adolescent girls? Why should it be accepted that they are subjected to violence and abuse? Why should it be accepted that they are simply not able to pursue the same education as boys? To date, because of discrimination and lack of rights, many adolescent girls in particular have seriously constrained choices and opportunities, limited possibilities to pursue their dreams, and effectively live a life of diminished expectations. The freedom to postpone or decide against marriage and children; access to family planning information and services; the empowerment of women; the education of children; and the assurance of comprehensive sexuality education will benefit people and societies. Together these measures help to reduce infant, child and maternal mortality; reduce teenage pregnancies and other unintended pregnancies; eliminate the risks of unsafe abortion; and arrest communicable diseases. Beyond this, they will help girls to stay in school longer and to find better jobs and women to live a more self-determined life.

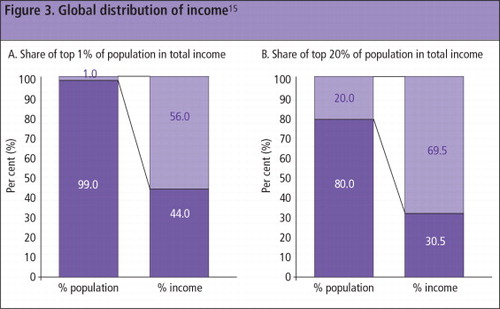

While many countries have made considerable progress towards, and virtually achieved, universal primary education, they are still lagging behind in secondary education. Furthermore, countries continue to have large gender disparities in secondary education. Few girls, compared with boys, make it into secondary school, and as compared with boys, fewer yet are staying in secondary school (). This disparity, which is particularly sobering in the poorest countries, is often attributable to discriminatory laws and practices, early marriage and child birth, as well as the need to care for the elderly and the sick, and support subsistence work at home. Yet, it is education beyond the primary level, together with access to sexual and reproductive health information and services that is essential for the empowerment of adolescents. Girls with secondary education typically postpone childbearing and have fewer children, and they invest more in each child. Therefore, these measures also contribute to lower fertility levels and slower population growth, and enlarge the possibilities for sustainable development.Citation45

Figure 6. Key indicators on education, latest available yearsCitation17.

In the coming years the international community at large and countries in particular must pay greater attention to addressing inequalities. More efforts must be made to encourage progress in the world’s poorest countries, but more emphasis must also be placed on helping the most marginalized populations in more advanced countries. In advanced countries a considerable share of the poor, especially in rural areas and in indigenous communities, do not have access to sexual and reproductive health information and services. But efforts in this area must go well beyond meeting the need for contraception. The availability of services and information must be go hand in hand with the protection of fundamental human rights and freedoms, and the fight against discrimination and coercion. The equal treatment of women and marginalized populations must be firmly established in law and practice, and must be actively promoted through policies and programmes. The empowerment of women cannot focus solely on reproduction; it must encompass all aspects of life.

The importance of forward-looking planning and evidence-based policies

Even if fertility levels were to drop significantly today, populations will continue to grow. And even as countries continue to have a growing population, they will begin to have an ageing population. Furthermore, while the process of urban population growth is almost completed in the developed countries, it is still ongoing in advanced developing countries, and it is just taking off in the least developed countries. Finally, accelerating international migration has powerful implications for both home and host countries. Population ageing, urbanization and migration are often associated with considerable challenges, but these population mega trends can also provide developmental opportunities. However, to realize these opportunities requires that policy makers systematically use population data and projections in order to plan ahead for the demographic futures of their countries.

Without knowledge of their populations – how many people are living and will be living, where they are living and will be living, and how old they are and how age structures will change – countries will not succeed in understanding and meeting the needs of their populations. For example, careful analysis of data can show how migration, urbanization and population ageing undermine traditional intra-family support systems, and can guide the establishment of modern and more formal support systems ahead of time. Furthermore, while planners will not know who exactly is moving to the cities in the next years, population projections provide a good understanding of the approximate size and age structure of the future city dwellers. If the authorities were to use this information systematically, they could contain the spread of unplanned settlements and mounting pressures on infrastructure, services and land. Without such planning, governments will operate in a permanent crisis mode. Instead of realizing the benefits of demographic changes, they will be confined to responding to and managing demographic challenges. Therefore, efforts to shape demographic trends through policies described above, must be complemented by efforts to anticipate and plan for demographic trends. The former cannot compensate for the latter.

Implications for the post-2015 development agenda

Although it is not clear whether even major changes in social, economic and environmental policies will suffice to ensure sustainable development, it is clear that without such changes it will be impossible. This article stresses that sustainable development, which is the declared objective of the post-2015 development agenda, will need to be built on three pillars:

| • | ensure green economic growth, | ||||

| • | promote more inclusive economic growth, and | ||||

| • | address and harness population dynamics through rights-based policies. | ||||

Progress in each of these areas is as much a collective global effort, which requires adequate support by bilateral and multilateral partners, as it is a national effort.Citation40 In an inter-dependent world, environmental and demographic changes have global implications – regardless of where they originate – and they therefore demand concerted global policy responses.

However, efforts to promote more inclusive economies – which are receiving particular attention since the global financial and economic crisis – must go hand in hand with serious efforts to promote green economies. The poverty-reduction agenda cannot distract from a green-growth agenda. Indeed, it would be misguided to view these two objectives as contradictory. Sustainable poverty reduction cannot be achieved without green growth. And in order to make progress towards both objectives, it is essential for countries also to shape their demographic futures.Citation46 As regards population dynamics, the analysis presented here has two overarching messages:

| • | Demography matters for sustainable development. Population dynamics pose challenges and provide opportunities for sustainable development. | ||||

| • | Demography is not destiny. Population dynamics can be effectively addressed through policies that respect and promote human rights. | ||||

While the global discussions recognize the need to promote greener economies, there is a greater resistance to promoting more inclusive economies, and neglect of the importance of addressing and harnessing population dynamics. To this end, the post-2015 development agenda must include the following ten goals:

| • | realize fundamental human rights, including sexual and reproductive rights, and eliminate discriminatory laws and practices; | ||||

| • | empower women to fully participate in economic, social, cultural, and political life; | ||||

| • | ensure investment in human capital throughout the life course, with a focus on health, education and social protection; | ||||

| • | ensure unrestricted, universal access to comprehensive sexual and reproductive health care services and information, including voluntary family planning; | ||||

| • | ensure education beyond the primary level, including continuing learning, and assure comprehensive sexuality education; | ||||

| • | promote productive and remunerative employment opportunities, and provide social protection to prevent people of all ages from slipping into poverty; | ||||

| • | ensure the systematic collection of essential data through vital registration, censuses and surveys; | ||||

| • | ensure that development strategies, policies and programmes are based on population data and projections; | ||||

| • | promote the sustainability of cities, and strengthen rural-urban linkages; and | ||||

| • | promote the developmental benefits of migration. | ||||

Finally, promoting sustainable development – defined as the well-being of current and future generations in harmony with nature – will need to pay special attention to younger people. By definition, sustainable development is to the benefit of younger people and the next generations, but at the same time it is important to underscore that progress towards sustainable development will only happen with the full involvement and support of young people. Hence, it is essential that the post-2015 development agenda places a particular focus on the empowerment of younger persons, which depends on adequate investment in their health, including sexual and reproductive health, and education, including comprehensive sexuality education.

Notes

* Inequality in Brazil, as measured by the Gini coefficient, fell from 59% in 2001 to 53% in 2007.Citation16

† Estimates based on World Bank,Citation17 UN,Citation4 and MeasuringWorth.com.Citation18

** The estimated changes in resource efficiency are highly sensitive to the measurement of output. If resource efficiency is measured in constant dollars and not adjusted for differences in purchasing power, many countries have not achieved rising resource efficiency.

* There is a large and growing literature focusing on the need for green economies and policies for sustainable growth;Citation13,22–28 the creation of green jobs and poverty reduction;Citation29,30 and the financial and macroeconomic implications of such structural shifts.Citation13,31 The shift towards green economies is best understood as a process of structural change. This change will have cost implications for individual companies, but does not need to have negative net effects on economic growth. Likewise it will imply changes in employment opportunities but does not need to have negative effects on overall employment. Green industries contribute to economic growth and create jobs, and they are a necessity for a sustainable rise in living standards.

* The lack of a governance system for global environmental goods is what HardinCitation33 suitably termed the tragedy of the commons.

* Even the high variant assumes a considerable decline in fertility from current levels. If today’s fertility levels remained unchanged, the world population would be set to reach 29 billion persons by the end of the century.

References

- United Nations. The Future We Want, Outcome document of the UN Conference on Sustainable Development, Rio de Janeiro, 20–22 June 2012.

- UN. Realizing the Future We Want for All, United Nations Task Team, Report to the Secretary-General, New York, 2012.

- UN. The Programme of Action, Report of the International Conference on Population and Development, Cairo, Egypt, 5–13 September 1994, UN, A/CONF.171/13/Rev.1. 1995.

- UN. World Population Prospects: The 2012 Revision – Key Findings and Advance Tables, New York, 2013. http://esa.un.org/wpp/. as at 24 March 2014.

- UN. The Millennium Development Goals Report 2013. 2013; New York.

- A Guscina. Effects of globalization on labor’s share in national income, International Monetary Fund (IMF) Working Paper 06/294. 2006; Washington, DC: IMF.

- International Monetary Fund. World Economic Outlook 2007: Globalization and Inequality. 2007; Washington, DC.

- Glyn A. Explaining labor’s declining share of national income, G-24 Policy Brief, No. 4. Washington, DC, 2010.

- International Monetary Fund and International Labour Organization. The challenges of growth, employment and social cohesion. Discussion document, Joint ILO-IMF conference in cooperation with the office of the Prime Minister of Norway, Oslo, 13 September 2010.

- M Herrmann. Reflections on globalization Global Youth Action Network Debating Globalization: International Perspectives on the Global Economic and Social Order. 2007; GYAN: Brussels.

- International Labour Organization. World of Work Report 2008: Income Inequality in the Age of Financial Globalization. 2008; ILO: Geneva.

- International Labour Organization. Global Wage Report 2008/2009: Minimum Wages and Collective Bargaining: Towards Policy Coherence. 2008; ILO: Geneva.

- UNCTAD. Trade and Development Report 2008: Commodity Prices, Capital Flows and the Financing of Investment. 2008; UNCTAD: Geneva.

- Credit Suisse. Global Wealth Databook 2013.

- I Ortiz, M Cummins. Global inequality: Beyond the bottom billion – a rapid review of income distribution in 141 countries. UNICEF Social and Economic Policy Working Paper. April. 2011; UNICEF: New York.

- International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth (IPC-IG). What explains the decline in Brazil’s inequality? One Pager, No. 89. July. 2009; IPC-IG: Brasilia.

- World Bank, World Development Indicators, http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators as at 24 March 2014.

- Measuring Worth.com, http://www.measuringworth.com/usgdp, as at 24 March 2014.

- Food & Agriculture Organization. FAO at Work 2009–2010: Growing Food for Nine Billion. 2010; FAO: Rome.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate change 2013: the physical science basis. IPCC Working Group I, Contribution to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2013; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

- U Hoffmann. Some reflections on climate change, green growth iIllusion and development space, UNCTAD Discussion Paper, UNCTAD/OSG/DP/2011/5. 2011; Geneva.

- HE Daly. Steady-State Economics: A New Paradigm. New Literary History. 24(4): 1993; 811–816.

- HE Daly. Beyond Growth: The Economics of Sustainable Development. 1997; Beacon Press: Boston.

- T Jackson. Prosperity without Growth: Economics for a Finite Planet. 2009; Earthscan: New York.

- World Bank. Inclusive Green Growth: The Pathways to Sustainable Development. 2012; Washington, DC.

- J-M Burniaux, J Chateau, R Dellink. The economics of climate change mitigation: How to build the necessary global action in a cost-effective manner? OECD Economics Department Working Paper No.701. 2009; Paris.

- International Monetary Fund. Climate, environment, and the IMF. Factsheet. March. 2014; IMF: Washington, DC.

- IWH Parry, RA de Mooij, M Keen. Fiscal policy to mitigate climate change: A guide for policymakers. 2012; IMF: Washington, DC.

- UN Environment Programme International Labour Organization International Organisation of Employers International Trade Union Confederation. Green Jobs: Towards Decent Work in a Sustainable, Low-Carbon World. 2008; UNEP: Nairobi.

- European Commission DG Employment. The jobs potential of a shift towards a low-carbon economy. Final Report. Published as OECD Green Growth Papers. 2012; Paris.

- World Economic Forum. The Green Investment Report: The Ways and Means to Unlock Private Finance for Green Growth, a report of the Green Growth Action Alliance. 2013; Geneva.

- RH Coase. The problem of social cost. Journal of Law and Economics. 3: 1960; 1–44.

- G Hardin. The tragedy of the commons. Science, New Series. 162(3859): 1968; 1243–1248.

- M Herrmann. Agricultural support measures of advanced countries and food insecurity in developing countries: economic linkages and policy responses. B Guha-Khasnobis, SS Acharya, B Davis. Food Security: Indicators, Measurement, and the Impact of Trade Openness. 2007; Oxford University Press: Oxford.

- UN Population Fund. Population Dynamics in the Least Developed Countries: Challenges and Opportunities for Development and Poverty Reduction. Report of UNFPA for the Fourth Conference on the Least Developed Countries. Istanbul, 9–13 May 2011. 2011; UNFPA: New York.

- UN Development Group. Population dynamics in the post-2015 development agenda. Report of the Global Thematic Consultation on Population Dynamics. 2013; UNDG: New York.

- UN. Report of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, Rio de Janeiro, 3–14 June 1992. Principle 6, A/CONF.151/26 (Vol. I). 12 August 1992.

- UN. World Population Policies 2009. 2009; UN: New York.

- Sustainable Development Solutions Network. Indicators for sustainable development goals. A Report by the Leadership Council of the Sustainable Development Solutions Network, Preliminary Draft for Public Consultation, 14 February 2014. http://unsdsn.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/140214–SDSN-indicator-report-DRAFT-for-consultation2.pdf

- UN Population Fund. Sexual and Reproductive Health for All: Reducing Poverty, Advancing Development and Protecting Human Rights. 2010; UNFPA: New York.

- UN Statistics Division. Millennium Development Goals Indicators. http://unstats.un.org/UNSD/MDG/Data.aspx

- UNICEF. Child Info. http://www.childinfo.org/. as at 28 March 2014.

- S Singh, JE Darroch. Adding It Up: Costs and Benefits of Contraceptive Services. Estimates for 2012. 2012; Guttmacher Institute and UNFPA: New York.

- UN. Monitoring of Population Dynamics, Focusing on Health, Morbidity, Mortality and Development, Report of the Secretary-General to the Commission on Population and Development, 43rd Session, 12–16 April 2010. E/CN.9?2010/4. New York, 2010.

- UN Population Fund. Impacts of Population Dynamics, Reproductive Health and Gender on Poverty. 2012; UNFPA: New York.

- UN Population Fund. Population matters for sustainable development. 2012; UNFPA: New York.