Abstract

Abstract

According to several sources, little progress is being made in eliminating the cutting of female genitalia. This paper, based on qualitative interviews and observations, explores perceptions of female genital cutting and elimination of the phenomenon in Hargeisa, Somaliland. Two main groups of participants were interviewed: (1) 22 representatives of organisations whose work directly relates to female genital cutting; and (2) 16 individuals representing different groups of society. It was found that there is an increasing use of medical staff and equipment when a girl undergoes the procedure of female genital cutting; the use of terminology is crucial in understanding current perceptions of female genital cutting; religion is both an important barrier and facilitator of elimination; and finally, traditional gender structures are currently being challenged in Hargeisa. The findings of this study suggest that it is important to consider current perceptions on practices of female genital cutting and on abandonment of female genital cutting, in order to gain useful knowledge on the issue of elimination. The study concludes that elimination of female genital cutting is a multifaceted process which is constantly negotiated in a diversity of social settings.

Résumé

D’après plusieurs sources, l’élimination des mutilations génitales féminines progresse peu. Cet article, fondé sur des observations et entretiens qualitatifs, étudie les conceptions de la mutilation génitale féminine et l’élimination du phénomène à Hargeisa, Somaliland. Deux groupes principaux de participants ont été interrogés : 1) 22 représentants d’organisations dont le travail se rapporte directement aux mutilations génitales féminines ; et 2) 16 individus représentant différents groupes de la société. Il apparaît que le recours à du personnel et du matériel médical s’accroît quand une fille subit une procédure de mutilation génitale ; l’utilisation de la terminologie est cruciale pour comprendre les manières actuelles de voir la mutilation sexuelle féminine ; la religion représente à la fois un obstacle et une aide d’importance pour l’élimination de cette pratique ; et enfin, les structures sexuelles traditionnelles sont actuellement remises en question à Hargeisa. Cette étude suggère qu’il est important de tenir compte des conceptions actuelles de la mutilation sexuelle féminine et du renoncement à cette pratique pour obtenir une connaissance utile de la question de l’élimination. L’étude en conclut que l’élimination des mutilations sexuelles féminines est un processus à multiples facettes qui est constamment négocié dans une multiplicité de contextes sociaux.

Resumen

Según varias fuentes, se han logrado pocos avances para eliminar la práctica del corte de los genitales femeninos. En este artículo, basado en entrevistas cualitativas y observaciones, se examinan las percepciones del corte genital femenino y la eliminación de este fenómeno en Hargeisa, Somalilandia. Se entrevistó a dos grupos principales de participantes: (1) 22 representantes de organizaciones cuyo trabajo tiene relación directa con el corte genital femenino; y (2) 16 personas que representan a diferentes grupos de la sociedad. Se encontró un uso creciente de personal y equipos médicos para efectuar el procedimiento de corte genital femenino; el uso de terminología es crucial para entender las percepciones actuales del corte genital femenino; la religión es tanto una barrera importante como facilitadora de eliminación; por último, las estructuras tradicionales de género están siendo cuestionadas en Hargeisa. Los hallazgos de este estudio indican que es importante considerar las percepciones actuales de la práctica de corte genital femenino y el abandono de ésta, a fin de adquirir conocimientos útiles respecto a la eliminación. El estudio concluye que la eliminación del corte genital femenino es un proceso polifacético constantemente negociado en una diversidad de entornos sociales.

For the last 20 years Somalia, located on the Horn of Africa, has been in a state of chronic conflict and instability.Citation1 In 1991, the government of Somalia was overthrown by a rival tribe, and Somaliland, in the North-West of the country, declared its independence. Since then, Somaliland has been operating as an independent state even though its independence is not recognised internationally. Puntland, a region in the North-East, also declared its autonomy in 1998.Citation2 Since 1991, southern Somalia has experienced frequent armed conflicts, and there has been no functioning government.Citation1 Somaliland, on the contrary, has conducted democratic elections and is commonly referred to as a relatively stable country undergoing recovery and reconstruction.Citation2 Hargeisa is the capital city of Somaliland, Somali is the official language and Islam is the predominant religion.Citation2

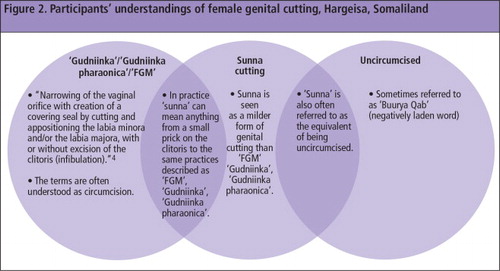

Cutting of female genitalia is referred to as female circumcision, female genital mutilation, female genital surgery and female genital cutting. SalamCitation3 points to the difficulties of meaningfully translating this phenomenon into English. The term female genital surgery, for example, is sometimes used to describe the practice in a neutral way. However, it has been criticised for referring to a social tradition in medical terms.Citation3 The practice of female genital cutting (FGC) involves “the partial or total removal of the female external genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons” (p.6).Citation4 JohansenCitation5 describes how the choice of terminology for FGC is highly value-laden. In her research among Somali immigrants in Norway, she found that “female genital mutilation” (FGM) was used to refer to “infibulation” only. This was problematic as it excluded a range of other practices commonly referred to as FGM. As a result, she changed her terminology to FGC during her research.Citation5 Similarly, in order to establish a mutual understanding of the practice between participants and researchers during the initial data collection for this paper, although various terms were used, the authors decided that the practices described by participants were best captured by the term FGC, except when quoting or describing the perceptions of participants and authors who used a different term.

FGC is predominately practised in Africa and Asia. Practices of FGC exist across all religions, and the origins of the practice are to a large extent unknown.Citation6 The WHO uses FGM when describing the practice, and further classifies it into four types. Type I: Partial or total removal of the clitoris and/or the prepuce, type II: Partial or total removal of the clitoris and the labia minora, with or without excision of the labia majora, type III: Narrowing of the vaginal orifice with creation of a covering seal by cutting and appositioning the labia minora and/or the labia majora, with or without excision of the clitoris (infibulation) and type IV: All other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes.Citation4

Of the four types of FGM identified by the World Health Organization (WHO),Citation4 two main forms exist in Somaliland: Pharaonic circumcision and sunna cutting.Citation6 Pharaonic circumcision is equivalent to infibulation, or WHO type III .Citation6 Sunna cutting corresponds to WHO type I, meaning the clitoris is partly or totally removed.Citation7 As will be seen, however, sunna cutting carries meanings and definitions beyond the WHO classification of type I. Somalian sources claim a prevalence rate of FGC of 95–98%, one of the highest in the world.Citation7–9 Data from the outpatient department at the Edna Adan hospital in Hargeisa, from 2002–2006 show that 97% of female patients had undergone FGC, of whom 99% had undergone the pharaonic form.Citation7

The first international conference on FGC was held by WHO in Sudan in 1979. It concluded that total elimination of the practice was needed. Over the next 20 years the philosophy of total and rapid elimination of FGC dominated initiatives, and the negative health consequences of the practice were emphasised.Citation10 In the 2000s there were few reliable accounts of prevalence.Citation10 Further, it was acknowledged by anti-FGC activists and organisations that approaches to elimination should recognise the broader social context, not simply targeting health complications and trying to measure results purely by drops in prevalence rates.Citation10

Despite the decades-long global campaign to eliminate FGC, it is still strongly embedded in Somali culture. Edna Adan Ismail is a former politician in Somaliland, and is currently the director and founder of the Edna Adan Maternity Hospital in Hargeisa. She has engaged greatly in the struggle for the elimination of FGC. In Somalia, Ismail made the first public declaration on stopping FGM at a governmental meeting in March 1977.Citation7 She continued to lobby to eliminate FGM until 1991, when the government was overthrown and campaigns against FGM collapsed.Citation7 It was not until 1997 that the revival of initiatives designed to eliminate FGM took place in Somaliland. Ismail, who was then a WHO representative in Djibouti, was asked to return to Somaliland to denounce FGM at the first seminar to revitalise efforts to eliminate the practice. After the seminar, several organisations and women’s groups initiated campaigns to eliminate FGM. In addition, a national committee and a regional taskforce were founded to develop policies on FGM.Citation7 This renewed focus led to the inclusion of FGM in a national gender policy, where it is categorised as a form of gender-based violence under the sub-heading ‘harmful traditional practices’.Citation11,12 However, there are currently no policies banning the practice in Somaliland.Citation11,12 The semi-autonomous region of Puntland, on the other hand, now has a policy banning all forms of the practice.Citation13

The renewal of anti-FGC efforts reflects an environment in which traditional ideas about FGC are being challenged and changes in how the practice of FGC is perceived appear to be taking place.Citation4,14 This paper looks at the changes that have occurred and what FGC currently constitutes in the minds of those involved with the practice. The paper assesses current conceptions of FGC, efforts to stop the practice and opinions on abandonment of the practice from a variety of stakeholders.

Methodology

The paper draws on data gathered from September to December 2011 in Hargeisa, Somaliland. A qualitative methodology using an explorative and emergent design, including in-depth interviews and observation, was utilised.

The first phase of data collection consisted of 16 interviews with 22 representatives of organisations working on reproductive health issues or FGC. Interviewees represented governmental and multilateral agencies, local and international non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and medical facilities. These interviews were conducted in English by the first author.

The second phase aimed to gain an understanding of FGC and its abandonment, including interviews with five nurses/midwives and two traditional birth attendants (TBAs), who also perform FGC of women. As the research evolved, nine lay representatives of different sections of society were recruited and interviewed by a female research assistant, including: two housewives, four beauticians, one religious scholar and two male students. The age of interviewees ranged from early 20s to mid-50s.

The initial interviews with the individuals working on FGC issues were arranged through prior contact. Following this, a snowball technique was used whereby initial interviewees were asked to suggest others with an interesting perspective on FGC who might be willing to participate in the research. These potential participants were then informed about the research and asked if they were willing to be interviewed for about one hour. The only criterion for selecting participants at this stage was that they were working on FGC-related topics.

For interviews with health workers and lay people, the first author and the research assistant visited hospitals and a maternal–child health clinic to recruit potential participants, and later two beauty salons. In each place permission to invite participants was sought from someone in charge. In this way two housewives and two men were recruited, and a religious scholar was recruited through an organisation working to stop FGC.

The interview guide contained open-ended questions on key themes to ensure that participants’ own understandings and opinions could emerge. The guide was adjusted as new topics were identified and included. Key topics addressed with those working on FGC issues were on their work related to FGC, and what types of FGC were present in Somaliland based on their experience. With health workers and lay people, questions covered thoughts on and experiences of FGC and views on the elimination of FGC.

All interviews, except one with a health worker, were voice-recorded. Interviews in English were transcribed verbatim by the first author immediately afterwards. Interviews in Somali were conducted by the research assistant with the first author present throughout. The research assistant briefly translated during interviews so that both of them were able to ask follow-up questions. After these interviews, the research assistant orally translated voice-recordings verbatim. These were also voice-recorded and subsequently transcribed by the first author. In the interview where a voice-recorder was not used, extensive notes were taken and a summary written together afterwards.

The first author also attended a workshop where the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, the Ministry of Religious Affairs and the Ministry of Health and Labour came together to make a common statement on FGM/C.Footnote*

As the literature on FGC, particularly in Somaliland, is scarce, reports, booklets and materials from organisations were collected to gain a better understanding of how FGC was currently perceived in Hargeisa. Posters presenting the health consequences of pharaonic circumcision at an outpatient ward in a hospital in Hargeisa, for example, illustrated that the focus of elimination campaigns was on pharaonic circumcison and health complications. Field notes based on informal conversations with Somalilanders who had returned from the diaspora, several expatriate medical staff working in Hargeisa, and participants in the FGM/C-workshop were also taken. Conversations with the research assistant were furthermore used to better reflect on and inform the research findings while in the field.

Upon returning from fieldwork, data were coded and analysed using Nvivo. Secondary literature was also reviewed in response to the themes that emerged from the preliminary analysis.

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Norwegian Social Science Data Services. In Somaliland, the Ethical Committee in the Ministry of Health and Labour gave formal permission to conduct the research.

Several practical limitations influenced the scope of the research. Due to the security situation, moving outside of Hargeisa was not possible without a mandatory police escort, but this was not financially viable. Being both female and Western also limited access to certain areas and people. These issues naturally influenced access to participants, and the study cannot claim to provide insights into other regions in Somaliland, particularly the rural areas. Nonetheless, it provides an important understanding of FGC in a sparsely researched area.

Findings

Defining FGC

Participants made a qualitative distinction between pharaonic circumcision and sunna cutting. Pharaonic circumcision was generally seen as the most severe form and was strongly associated with the past:

“[G]irls would face a lot of problems with circumcision, with the pharaonic type. They used to use sticks and woods to stitch it, and later on they used to tie her and make her unmovable for seven days. After that when she needs to urinate it is really hard and it causes a lot of pain, but she has to handle it.” (Nurse, in her 20s)

Sunna cutting, on the other hand, was seen by all participants as a more recent and milder practice. Most participants expressed that this less severe form of FGC was a good thing:

“Thanks to God that we get removed from that type [pharaonic] and now we get into this new type [sunna] which is better for her [referring to daughter].” (Housewife, in her 40s)

However, pharaonic circumcision was still considered common. According to one participant who had researched FGC for many years, sunna cutting could be a very minor procedure involving nothing more than a small incision in the clitoris. However, a number of participants pointed out that there was no common understanding or definition of sunna, and in practice it could be as severe as pharaonic circumcision:

“In the end there is no practitioner or doctor that will teach you to perform this practice [sunna] […], and they are not trained. So some of them will even do an infibulation and they will tell the mother who doesn’t know anything that it is sunna.” (Local NGO worker)

Some talked about girls being buurya qab, the Somali term for a girl who has not undergone any form of FGC, which also came up in a number of interviews. This was described in negatively laden words, with some participants claiming that to be a buurya qab was “a big challenge” and “not good”.

Translating the terminology from English into Somali

In preparing questions for the interviews, important definitional differences when translating the word “circumcision” into Somali were discovered. The distinction between pharaonic circumcision and sunna cutting was not always captured using common English descriptions. The acronym FGM rather than “female genital mutilation” itself has entered Somali vocabulary and was commonly used by the health workers. “Circumcision” was thus initially translated into the Somali terms FGM, gudniinka or gudniinka fircooniga (pharaonic circumcision). A number of participants, however, saw no contradiction in stating that they would under no circumstances let their daughters undergo FGM or gudniinka, yet they did consider it important for their daughters to have sunna cutting:

“I want to stop all the circumcision [‘gudniinka’] […]. We should continue the sunna […]. It [gudniinka] is not something in our religion […]. Sunna is not something that has a problem. It causes no problems, no harm and it’s not a big surgery. Just a small surgery and after it they’re all ok.” (Male student, early 20s)

Thus, the common assumption among English speakers in Somaliland that “FGM” refers to all forms of female genital cutting is wrong. The disjuncture is illustrated on the T-shirt used in a local NGO’s campaigns against FGM in . While the T-shirt reads “Eradicate FGM from Somaliland” in English, the Somali text says “Eradicate pharaonic circumcision from Somaliland”. Furthermore, a recent promotional movie by an international NGO claims to demonstrate that FGM is being abandoned in Somaliland.Citation15 In the same way as in the t-shirt, the movie uses “FGM” in English subtitles translating pharaonic circumcision. In other words, it is the elimination of pharaonic circumcision, not all forms of FGC, that is evident. Combinations of the word sunna with gudniinka were not used. Therefore sunna may be seen as a practice that exists outside of gudniinka and FGM, which does not have to be eliminated because it is in another category altogether. The understandings of the term “female genital cutting “on the part of participants is conceptualised schematically in .

As the figure illustrates, there is not a complete conceptual separation between the different practices. However, a girl/woman who has undergone sunna cutting cannot be called buurya qab.

Sunna cutting: seen as a new and better form

Sunna cutting was frequently described by health workers and lay people as new and modern, and a better alternative than pharaonic circumcision. Most participants perceived sunna cutting as having no medical complications:

“[N]owadays they just do this small incision without any problems. And they leave her and later, at the time of delivery, she would have no problems.” (TBA with long experience in circumcising girls)

The social implications of replacing pharaonic circumcision with milder forms of cutting are, however, uncertain. A number of participants suggested that girls who had undergone sunna cutting may still face social exclusion and difficulties in marriage:

“[Some people] think that this girl who got the sunna is not a good girl, and she might have had sex before getting married…. But if she’s closed and got stitches she’s a good girl.” (Beautician)

Changing practice was described regarding the younger generation. Most participants stated that young mothers will now only perform sunna cutting on their daughters. One of the housewives, who was in her 50s, explained that her two oldest daughters had undergone pharaonic circumcision, while her three younger daughters had undergone sunna cutting. Her reasons for this were that the awareness-raising campaigns taught her that pharaonic circumcision was harmful and not a religious obligation. She therefore decided not to let her younger daughters go through what she herself had done. Thus, although not fully recognised as circumcision, sunna cutting is seen by many as a necessity, that reflects religious obligation and what it means to be a female.

Moves towards use of medical facilities and medical staff

FGC appears to be increasingly understood in biomedical terms and practiced in medical facilities. Several representatives of organisations claimed that knowledge of the health complications of pharaonic circumcision had become widespread:

“Everybody in the capital, everybody can state the complications. Everybody knows the problem of FGM. Everybody can name the complications.” (Local NGO worker)

However, this participant also argued that knowledge of the health complications of pharaonic circumcision alone was not enough for people to abandon the phenomenon. One of the beauticians agreed that, although in general people know a lot about the health problems of pharaonic circumcision, she insisted that there had not been much change as some men still prefer to marry someone who has undergone pharaonic circumcision.

Several participants explained that in the past it was the norm for FGC to take place in the family home. However, nowadays there are other options and many now choose for the procedure to be undertaken at a hospital or other medical facility. Several participants claimed that FGC was usually carried out by a nurse, a midwife or a TBA who has had at least some basic medical training. Participants also emphasised the difference between TBAs who had been exposed to some medical training and traditional circumcisers, who often had not. A TBA was described as someone who is medically skilled and makes use of medical equipment. A circumciser was described as someone who is not a health worker and who may use unclean equipment. The skills of a circumciser were said to be passed down through their family, as opposed to being formally taught. A circumciser was seen as someone who based their practice within tradition and culture, while a TBA was seen as someone whose practice is based within biomedicine. According to two of the nurses, as the practice of pharaonic circumcision has come under criticism, using a traditional circumciser is often more secretive than it was in the past.

Decision-making

Decision-making emerged as an important theme when describing FGC. Most participants claimed that it was the mother’s role to decide if, when and how FGC would happen:

“90% depends on the mother, but 10% sometimes depends on the father. In our culture men are only supposed to take care of things outside, and the mother is the one who is directly responsible for the kids, and that is why she takes responsibility for that decision.” (Beautician)

Several of the health workers and lay people also talked about the tradition of ensuring that a girl has undergone FGC when the time comes to marry. Some of the older participants stated that the families of the two spouses discussed FGC before permission to marry is granted. Most of the younger participants, however, claimed that it is only the couples that talk about FGC before marriage. A number of lay people, health workers and NGO workers recounted stories of newly-wed husbands who immediately divorced their wives upon finding that they were not circumcised or had only undergone sunna cutting. In these instances it was considered to be a great shame for the girls’ mothers, and they were blamed for not looking after their daughters’ futures.

However, it was apparent from statements by some of the younger participants that even though primary responsibility for FGC lies with the mother, the father could also have a say in influencing the decision:

“If I get married and if I have a daughter, I’ll tell my wife not to circumcise my daughter.” (Male student, early 20s)

One of the housewives in her 50s thought that older mothers and grandmothers could be convinced that pharaonic circumcision is bad, and as they were well respected in society, they could influence the decision whether to circumcise younger girls. One beautician illustrated the strong position of elders by encouraging more awareness-raising campaigns:

“I encourage more awareness campaigns for the people, and specifically for the older mothers, because even the young mothers face problems because they face pressure from the family and the relatives.”

While FGC is clearly seen to belong almost exclusively within the female realm, it is apparent that wider family and social structures can also play important influencing roles when it comes to decision-making.

Religion: a barrier and facilitator of elimination

While there is growing acceptance that pharaonic circumcision is not religiously sanctioned, religious ideas about sunna cutting seem to be more ambiguous. The argument that Islam has banned pharaonic circumcision was given as a key reason by many to abandon it. Most NGO workers interviewed said that it is not a religious obligation to undergo FGC, but that in general lay people believe it is. The religious scholar interviewed explained that although it is not a religious obligation, the religious writings can be interpreted in such a way that the girl herself has the choice whether or not she wants to undergo FGC. Most lay people and health workers thought that pharaonic circumcision was a cultural tradition, not a religious obligation. However, both lay people and health workers in this study perceived sunna cutting to be a religious obligation:

“People want to continue sunna because it’s in our religion, and people like to do what is in our religion. If that thing is not in our religion they would not do it.” (Male student, early 20s)

Moreover, although several religious scholars have claimed that FGC of any form is not part of Islam, religious leaders in Hargeisa currently claim that sunna cutting is a religious obligation.6,16 It is at this point of conceptual and religious ambiguity about FGC that present day Somaliland exists.

During the FGM/C workshop, one of the representatives of the Ministry of Religious Affairs explained that he had discussed sunna cutting with several religious scholars, both in Somaliland and abroad, and that he had come to the conclusion that sunna cutting is a religious obligation:

“It is something written in our religion. I asked a lot of sheikhs about this outside the country, even some of the biggest ones… I researched a lot…. The ones who circumcise are the ones who really follow the religion…. It is better than not circumcising.”

One of the representatives of the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs challenged the view that sunna cutting is commonly practised outside Somaliland. She argued that because the Middle East is the origin of Islam, Somaliland should follow the religion as it is interpreted there. She therefore claimed that religious texts should be interpreted as meaning that no form of FGC is a religious requirement:

“I think that the Arab sheikhs are better than us at interpreting this, since the Quran in our religion is in their language…. In the Arabic language there is a phrase that can have different meanings.… It says that the Prophet said not to circumcise the girl. It says to do circumcision for the boys, not for the girls.”

During the FGM/C workshop, it was observed that religious leaders were accorded enormous respect. If a religious leader or scholar wanted to speak during the discussions, everyone stopped talking and listened. This was not a courtesy shown to other individuals who attempted to break into the discussion. It is clear that religious leaders and scholars are key actors in shaping and directing social interpretation of FGC.

Discussion

Elimination of FGC, where abandonment follows a steady decrease in prevalence rates, is not straightforward nor easily achieved. This paper argues that people’s perceptions of FGC need to be considered in order to understand the practice and its possible abandonment. What became clear in this study is that current understandings of FGC are different to those of the past, but the idea that some form of genital cutting is necessary remains.

Public awareness campaigns focusing on the health complications of FGC have shifted the discourse from one based purely in tradition and culture to one based, at least in part, on biomedical science. This has created the space for new ideas and understandings to emerge, and as a result, pharaonic circumcision appears gradually to be declining. Conversely, the focus on the health complications of pharaonic circumcision has also been interpreted as an implicit endorsement of sunna cutting, which is commonly considered to be without medical complications.

Indeed, a major criticism of approaching FGC as a purely biomedical issue is that although there may be a reduction in the severity of the practice, little progress appears to have been made in reducing prevalence rates.Citation8 The survey at the outpatient department at the Edna Adan Hospital in 2009 supports this criticism, especially since 99% of those who had undergone FGC have undergone infibulation.Citation7 This may be of concern to those working to eliminate FGC, particularly considering that the practice of sunna cutting is poorly defined and can in fact be as severe as the pharaonic version. Although there is a change in terminology, it does not necessarily reflect a change in the practice.

On the other hand, other research suggests that there has been a trend towards milder forms of FGC in countries where medicalisation is apparent.Citation6 In Somaliland more recent research also indicates that there has been a move towards milder forms,Citation4,14 something that may be evidenced by the fact that girls are more likely to undergo the procedure in a medical facility where staff have received at least some medical training.

Nevertheless, those working to stop FGC need to take seriously the meanings that come to reside in key concepts and how these relate to practice. Whether by design or not, efforts to eliminate FGC in Somaliland have been focused on the elimination of pharaonic circumcision, rather than all forms of FGC.Citation16 Thus, it is necessary to acknowledge both local and international use of terminology and the dialectical relationship between them when it comes to designing initiatives to eliminate FGC. A recurrent theme in this paper is that FGC is not clearly defined locally. Without an understanding of how it is defined it is difficult to ensure shared understandings. As a result, false conclusions may be reached about the practice of FGC. In particular, what currently constitutes sunna cutting is unclear and needs to be understood in order to know what impact initiatives designed to stop the practice have had, as well as what still remains to be done. What does appear certain is that changing terminology offers the opportunity for social change.

It is clear that religious debate has been integral in shifting opinion against pharaonic circumcision towards sunna cutting. This demonstrates the dual role religion can have as both a facilitator of abandonment and an enforcer of FGC practices. While current opinion appears to support the idea that sunna cutting is a religious obligation, this is an area that can change as religious dialogue continues. It is at the very least ambiguous as to whether religious texts should interpret FGC as an obligation, or not as an obligation but as an acceptable practice, or not as an acceptable practice at all. Importantly, the existence of differing religious points of view offers new possibilities for debate. This offers the opportunity for reconstruction of ideas and practices, and is an important point of engagement for those working towards elimination of FGC. However, this is not without risk as it is not clear that religious debates will be settled in favour of elimination.

Gender roles in the sunna generation

Up-to-date prevalence rates of FGC in Somaliland are uncertain, but it is widely believed that the younger generation of mothers-to-be prefer to let their daughters undergo sunna cutting, if any cutting at all. This younger generation, which can be called the ‘sunna generation’, bring new meanings to established FGC practices. This has occurred through a new vocabulary and by challenging perceptions of traditional decision-makers.

Talle and JohnsdotterCitation6,17 claim that FGC in Somalia is a ritual that only involves women and that men have little influence in decision-making. This is partially supported by the findings of this study. However, as FGC practices are changing, the sunna generation seem to have a different understanding of FGC than the older generation. The findings indicate that other social actors, such as fathers and husbands, can have an influence on decision-making.

Due to the campaigns designed to eliminate FGC, both men and women in the sunna generation are more aware of what girls will go through, and some claim they have realised that this is not something that their daughter should need to endure. Men should not be a missing component in FGC campaigns; they are just as much part of a negotiated culture which may bring new understandings of a lived reality into being. Several studies show that men are potentially powerful decision-makers in women’s matters in Somali society.Citation6,17 Yet the younger generation will also have to negotiate these issues with the older generation. It is therefore useful to understand the meaning of gender roles and the relationship between the younger and older generation in Somaliland society. Further, it is important to acknowledge that social and cultural organisation is flexible and open to change. Through the sunna generation, the construction, or rather reconstruction, of gender can be a powerful agent for change. How sunna cutting comes to be defined, and how this definition can be linked with changing gender roles, may become part of a crucial battleground in the drive to change practices and abandon FGC.

Acknowledgements

This work is based on Ingvild Lunde’s MPhil thesis in International Community Health, submitted to the Institute of Health and Society, University of Oslo, May 2012. She thanks Ingvill Krarup Sorbye, at Oslo University Hospital, for co-supervising the thesis. The authors want to thank all the participants who openly shared their knowledge and opinions.

Notes

* *Inter-Ministerial dialogue and consensus for the development of Ministerial statement on FGM/C abandonment, 28–29 November 2011.

References

- A Abby, D Mahamoud. Internally displaced minorities in Somalia and Somaliland. 2005. http://www.mbali.info/doc345.htm

- M Bradbury. Becoming Somaliland. 2008; Indiania University Press: Bloomington.

- S Salam. Language is both subjective and symbolic. Reproductive Health Matters. 7(13): 1999; 121–123.

- UN Children’s Fund. Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: a statistical overview and exploration of the dynamics of change. July. 2013; UNICEF: New York.

- REB Johansen. Experiences and perceptions of pain, sexuality and child birth. A study on female genital cutting among Somalis in Norwegian exile, and their health care providers PhD thesis. 2006; University of Oslo: Faculty of Medicine.

- A Talle. Kulturens makt: Kvinnelig omskjœring som tradisjon og tabu [The power of culture: Female genital cutting as tradition and taboo]. 2010; Høyskoleforlaget AS: Kristiansand.

- EA Ismail. Female genital mutilation survey in Somaliland. 2009; Edna Adan Maternity and Teaching Hospital: Hargeisa.

- M Black. Eradication of Female Genital Mutilation in Somalia. 2010; UNICEF: Somalia.

- IK Sorbye, B Leigh. Reproductive health national strategy and action plan 2010–2015: Somalia. 2009; WHO: Somalia.

- N Toubia, E Sharief. Female genital mutilation: Have we made progress?. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 82(3): 2003; 251–261.

- Ministry of Family Affairs and Social Development. Second draft national gender policy framework 2008–2011. Submitted to the Council of Ministers, Government of the Republic of Somaliland. Hargeisa, Somaliland; 2008.

- Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs. National Plan against FGM in Somaliland. 2011; Hargeisa, Somaliland.

- UNICEF. Regional authority in Somalia introduces an official policy to end FGM/C. 14 March 2014. http://www.unicef.org/somalia/reallives_14437.html

- AG Abdi, BP Bø, J Sundby. Attitudes toward female circumcision among men and women in two districts in Somalia: is it time to rethink our eradication strategy in Somalia?. Obstetrics and Gynecology International. ID 312734: 2013; 1–12.

- Totsan. My daughter dry your tears. Video, 2011. http://vimeo.com/32516740

- UJ Gulaid. The challenge of female genital mutilation in Somaliland: ongoing research and policy discussions. Finnish Journal of Ethnicity and Migration. 3(2): 2008; 90–91.

- S Johnsdotter. Projected cultural histories of the cutting of female genitalia: a poor reflection as in a mirror. History and Anthropology. 3(2): 2012; 74–82.