Abstract

This paper reports the views of participants from key multilaterals and related agencies in the evolving global negotiations on the post-2015 development agenda on the strategic location of sexual and reproductive health and rights. The research was carried out in June and July 2013, following the release of the report of the High-Level Panel of Eminent Persons on the Post-2015 Development Agenda, and comprised 40 semi-structured interviews with 57 participants and two e-mail respondents. All respondents were responsible for the post-2015 health and development agenda, or the post-2015 agenda more broadly, within their organisations. The interviews provide an insight into the intention to ensure that sexual and reproductive health and rights are integrated into the post-2015 trajectory by key players who sit at the interface of UN and Member State interaction. They reveal both an awareness of the shortcomings of the Millennium Development Goal process and its impact on advocacy for sexual and reproductive health and rights in early post-2015 engagement, as well as the vulnerability of sexual and reproductive health and rights in the remaining phases of post-2015 negotiations. Recent events bear these concerns out. Ensuring sexual and reproductive health and rights are included in the final post-2015 outcome document in the time remaining for negotiations, will be anything but a “doddle”.

Résumé

Cet article expose les idées des participants d’institutions multilatérales clés et d’organes apparentés aux négociations internationales sur le programme de développement de l’après-2015 et la place stratégique de la santé et des droits sexuels et génésiques. La recherche a été menée en juin et juillet 2013, après la publication du rapport du Groupe de personnalités de haut niveau chargé du programme de développement pour l’après-2015. Elle comportait 40 entretiens semi-structurés avec 57 participants et deux répondants par courriel. Tous les répondants étaient responsables du programme de santé et de développement de l’après-2015 ou, plus généralement, du programme de l’après-2015 au sein de leurs organisations. Les entretiens ont dénoté la volonté des acteurs clés qui siègent dans l’interface entre les Nations Unies et les États Membres de garantir l’intégration de la santé et des droits sexuels et génésiques dans la trajectoire de l’après-2015. Ils montrent aussi une sensibilisation aux lacunes du processus des objectifs du Millénaire pour le développement et son impact sur le plaidoyer pour la santé et les droits sexuels et génésiques dans l’action précoce de l’après-2015, mais aussi une prise de conscience de la vulnérabilité de la santé et des droits sexuels et génésiques dans les phases restantes des négociations sur l’après-2015. Les événements récents confirment ces craintes. Assurer l’intégration de la santé et des droits sexuels et génésiques dans le document final sur l’après-2015 pendant le délai qui reste pour les négociations sera tout sauf facile.

Resumen

Este artículo informa sobre los puntos de vista de participantes provenientes de organizaciones multilaterales e instituciones afines en las negociaciones mundiales en evolución en la agenda de desarrollo post 2015 respecto a la situación estratégica de salud y derechos sexuales y reproductivos. La investigación fue realizada en junio y julio de 2013, después de publicado el informe del Grupo de Alto Nivel de Personas Eminentes sobre la Agenda de Desarrollo Post 2015, y consistió en 40 entrevistas semiestructuradas con 57 participantes y dos informantes por correo electrónico. Cada persona era responsable en su organización de la agenda de desarrollo y salud post 2015, o la agenda post 2015 en general. Las entrevistas nos permitieron comprender mejor la intención de asegurar que salud y derechos sexuales y reproductivos sean integrados en la trayectoria post 2015 por actores clave en el punto de interacción entre las Naciones Unidas y los Estados Miembros. Revelan conciencia sobre las deficiencias del proceso de los Objetivos de Desarrollo del Milenio y su impacto en la promoción y defensa de salud y derechos sexuales y reproductivos al iniciar la agenda post 2015, así como la vulnerabilidad de salud y derechos sexuales y reproductivos en las fases restantes de las negociaciones post 2015. Recientes eventos confirman estas inquietudes. En el tiempo que resta de las negociaciones, será un reto asegurar la inclusión de salud y derechos sexuales y reproductivos en el documento final de resultados post 2015.

“ICPD was anything but a doddle, but it looks like child’s play by comparison to this.” Citation1

The November 2013 edition of Reproductive Health Matters examined global planning around the evolving post-2015 development goal agenda, which will lead to the next iteration of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) when they expire on 31 December 2015. The explicit inclusion in the post-2015 framework of gender equality, and sexual and reproductive health and rights in particular, is anything but assured with two years of negotiations remaining. Nonetheless, early positioning of sexual and reproductive health and rights in negotiations in 2012 and 2013 was encouraging,Footnote* and their prominence was maintained when the UN sponsored High-Level Panel of Eminent Persons on the Post-2015 Development Agenda (High-Level Panel) proposed 12 illustrative goals that included a goal on gender and a sexual and reproductive health and rights target as one of five targets under the illustrative umbrella health goal (Goal 4 Ensure Healthy Lives: Target 4D; Ensure universal sexual and reproductive health and rights).Citation2 The Sustainable Development Solutions Network’s counter proposal of 10 Sustainable Development GoalsCitation3 emphasised sexual and reproductive health and rights more forcefully in the targets of two proposed goals relating to environmental sustainabilityFootnote* and health and well-being.Footnote† In keeping with the High-Level Panel, the Sustainable Development Solutions Network proposed a separate gender equality goal.

Despite this positive framing within both post-2015 processes, sexual and reproductive health and rights commentators insist that advocates remain vigilant right through to the end of the Member-State negotiated post-2015 document.Citation1,4,5 While it was thought that the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) Beyond 2014 was occurring at a fortuitous time, and would fuel momentum for integrating sexual and reproductive health and rights into the post-2015 paradigm,Citation6 it has in fact triggered serious conservative opposition. This raises questions as to how ICPD Beyond 2014 outcomes will be fed into the post-2015 process.Citation4

Based on history, this caution is justified: the outcomes of the broadly endorsed ICPD +5 Review (1999) were not incorporated into the MDGs by their drafters.Footnote** Although commentators claim the eight MDGs were a technical synthesis of the major UN Summit and Conference outcomes of the 1990s,Citation7,8 clearly this was not the case. The content of the ICPD Programme of Action in Cairo in 1994, for instance, was sidelined.Citation9 Furthermore, the 1995 Beijing Platform of Action’s 12 areas of concern were integrated into the MDGs “in a way that reduced their critical edge and left out the holistic approach of the Platform of Action”.Citation10

Despite the MDG review in 2005 acknowledging the “centrality of sexual and reproductive health and rights in ending poverty”, the formal addition of a reproductive health target in 2007 (“Target 5B: Achieve, by 2015, universal access to reproductive health”), within the MDGs depended on a huge advocacy effort.Citation11 At the same time, critics had highlighted “the complete inadequacy of the targets and indicators associated with MDG 3 in capturing the goal of women’s empowerment”.Citation12

Up to this writing, the open nature of post-2015 planning has created a very different and more favourable negotiating landscape for sexual and reproductive health and rights advocates; the antithesis of the closed planning period preceding the MDGs. Marked differences are evident through the highly participatory nature of the “global conversation” surrounding early post-2015 negotiations,Citation13 and the shift in post-2015 decision-making from the UN to the Member States. Further, unlike the human development paradigm underscoring the MDG agenda, the post-2015/Rio+20 Sustainable Development Goal paradigm has three pillars (social, economic and environmental),Citation14 with Jeffrey Sachs, Director of the Sustainable Development Solutions Network, outlining a fourth governance pillar.Citation15 While variants of the economic and environmental pillars received prominence within the MDG framework, the social pillar (grounded in achieving social inclusion and overcoming social discrimination and inequitable state practices) is obviously important for post-2015 sexual and reproductive health and rights advocates.

This qualitative study examines the strategic location of sexual and reproductive health and rights in the post-2015 dialogue in mid-2013 through in-depth interviews with participants from key multilaterals and related agencies working on health in the post-2015 development agenda, some of whom are specifically tasked with advancing sexual and reproductive health and rights in the post-2015 paradigm. The interviews provide an insight into the intention to ensure that sexual and reproductive health and rights are integrated into the post-2015 trajectory by key players who sit at the interface of UN and Member State interaction. They reveal both an awareness of the shortcomings of the MDG process and its impact on advocacy for sexual and reproductive health and rights in early post-2015 engagement, as well as the vulnerability of sexual and reproductive health and rights in the remaining phases of post-2015 negotiations.

In many respects, this research responds to Ortiz Ortega’s call for the sexual and reproductive health and rights community:

“…to invest in continuous political analysis that can help us to understand better the places where we are able to have influence and those where we are unable to influence … [in order to] identify how to shift the gears of power once more in favour of the deep-seated change we have so comprehensively and carefully envisioned.” Citation10

Methods

This is a qualitative policy analysis from a social constructivist and phenomenological perspective. It uses discourse analysis to locate the high-level policy debate on health goals in the broader discourse of the formulation of the post-2015 development goals in mid-2013.Citation16,17 Document analysis and in-depth interviews enabled an examination of discourse in its social, political, cultural and historical context.Citation18–21

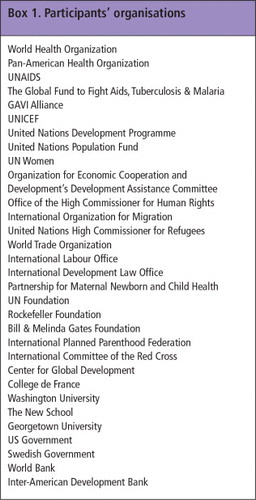

The interviews were conducted over five weeks in June/July 2013 just after the High-Level Panel released its May 2013 report. Participants were purposively recruited from multilateral organisations and associated agencies; the criterion for selection was that they were responsible within their organisations for health in the post-2015 development goal agenda. We began by listing the multilaterals, primarily UN organisations, key development banks and global public-private partnerships with UN health organisations. Additional informants directly linked to the health multilaterals and the post-2015 agenda from government, academia, civil society and philanthropy were identified from the draft report of the Global Thematic Consultation on Health, February 2013, and professional networks (Box 1).

Following initial contact by e-mail and/or telephone we explained the purpose of our study and asked for a face-to-face interview at each participant’s office (mainly in Washington DC, New York, Paris and Geneva). Interviewees were also asked to identify others who were involved in the post-2015 agenda and to provide contact details and, where appropriate, introductions. This sampling strategy allowed flexibility, once in the field, to take advantage of events and relationships for locating additional key informants.Citation22,23

Forty semi-structured interviews were carried out in total, comprising 33 face-to-face interviews and seven by Skype with 57 participants (31 men and 26 women); two additional participants provided e-mail responses. Participants were from a total of 31 agencies: 17 multilaterals, four academic institutions, three foundations, three non-government organisations (NGOs), two government agencies, and two development banks.

Five questions were asked, adapted for the participants’ role and organisational context:

How was the participant’s organisation engaging in post-2015 goal discussion?

What did the participant think about the High-Level Panel report, particularly the “Ensure Healthy Lives” goal?

What were the participant’s thoughts on the confluence of the Sustainable Development Goals and the post-MDG poverty reduction agenda?

What were the likely challenges in reaching global consensus on the post-2015 goals?

Which key actors outside the UN were likely to emerge in negotiating the post-2015 goals?

With participants’ consent, interviews were digitally-recorded and transcribed by a professional transcription service. Three participants requested a copy of their transcript to review prior to analysis. During three face-to-face interviews participants requested the digital recorder be turned off for a short time. At least ten participants from different agencies requested that any quotes published were de-identified and not attributed to their organisation, for two reasons: The sensitive nature of the discussions vis à vis their ongoing institutional involvement in post-2015 negotiation would otherwise have constrained their responses, and the finite number of professionals working on post-2015 matters in each organisation risked identification of their positions. Respondents were assigned an interview number such as lv1550 (without qualification, as opposed to an individual participant number) to differentiate interviews but avoid identifying participants.

Guided by Attride-Stirling’sCitation24 approach to thematic analysis, CEB entered the transcripts into NVIVO 9 and engaged in a systematic immersion in the data. To heighten analytical rigour and inter-rata reliability, PSH independently reviewed CEB’s coding tree, and both researchers discussed their analysis of the material, and finally agreed on five thematic coding categories and their application.

Analysis for this paper was limited to responses from 19 of the 57 participants from 16 of the 31 different organisations who directly addressed issues of sexual and reproductive health and rights in the post-2015 context. Unsurprisingly, the bulk of participants who provided comment were from health and/or gender and rights-focused multilaterals, but we have not specified these for reasons of anonymity. As we did not pose specific questions on sexual and reproductive health and rights in the interviews, our findings represent perspectives on sexual and reproductive health and rights volunteered by representatives of these agencies engaged in the post-2015 process, not elicited from them.

Ethics approval was from the University of Queensland’s School of Population Health Ethical Review Committee.

Findings

Impact of omitting sexual and reproductive health and rights from the MDGs

“This is not going to happen again!”

Most of the 57 participants prioritized inclusion of the unfinished business of the health MDGs in the post-2015 development goals, particularly emphasizing MDG-5 on maternal health: “The MDGs that haven’t been achieved on maternal mortality, they are quite slow, but we just can’t chuck this stuff to the side” (Iv1587). Two UN representatives reflected at length on the omission of sexual and reproductive health and rights in the original goals, and the resulting under-achievement. Although stakeholder advocacy had ensured that “universal access to reproductive health” became one of the MDG-5 targets in 2007, its belated inclusion meant countries had much less time to make meaningful inroads into its attainment (Iv1552). Concern was also raised that concentration on implementation of a narrow maternal mortality goal had deflected attention from other important sexual and reproductive health and rights issues.

The 19 participants who discussed sexual and reproductive health and rights pointed to a range of stakeholders (including UN agencies, NGOs, women’s groups, advocacy coalitions) determined that “these issues will not fall again from the next development agenda” (Iv1552). One UN participant considered the failure to include sexual and reproductive health and rights in the original MDGs a “defeat” and “a lesson that we need to learn [from]” (1v1552), arguing that this lesson must not be repeated in the post-2015 and ICPD Beyond 2014 context. He conceded that during the period leading up to the formulation of the MDGs, “UNFPA and many stakeholders… were overconfident” of the inclusion of sexual and reproductive health and rights. This overconfidence was particularly due to the momentum resulting from the ICPD in 1994: “In a sense [people/organisations were] saying okay, that’s a piece of cake” (1v1552).

The global spotlight on sexual and reproductive health and rights in 1999 seemed to justify these presumptions, as the review of the first five years of ICPD implementation, undertaken in a series of meetings, resulted in “Key Actions for the Further Implementation of the ICPD Programme of Action” and received broad support in the special session of the UN General Assembly (ICPD+5) in June 1999:

“We thought that having an ICPD reaffirm[ation]… was perfect but we didn’t realise that it was equally important, even perhaps more important, to be reflected in the MDGs… I mean [there was a sense that] the MDGs will have all these [outcomes] reflected because the Member States have just approved this… We didn’t realise the more conservative sectors were really coming very prepared. At that point in time, the Group of 77 [was] divided… but also… at that time the UN workers, diplomats leading the process, didn’t want to open the mess… They wanted to have a smooth process in the MDGs… I’m feeling we need to learn from that because I think we found there are some… in the UN thinking exactly the same [now]: ‘This issue – I know we agree, we want to have it but it’s conflict’. It’s difficult. It’s divisive. So we need to be very strong in saying well, this is not going to happen again!” (1v1552)

Early mobilisation of stakeholders in post-2015 engagement

“There are a lot of active players.” (Iv1566)

Compared to the UN closeting the world’s eyes from MDG planning, the consultative and participatory nature of the early UN-led post-2015 development agenda process was seen by several participants as benefiting the sexual and reproductive health and rights advocacy agenda: “The whole world is watching, which is almost the exact opposite of where we were in 2001.” (Iv1551) One participant was particularly buoyed by the strong leadership in the present-day UNFPA.

We found disillusionment with the politics of the MDG process, and its sidelining of sexual and reproductive health. Compared to participants from the other multilateral organisations, participants from agencies specifically involved in sexual and reproductive health and rights indicated their organisations had been planning future advocacy efforts well before the UN Secretary-General launched the post-2015 consultative process in 2012.

They spoke of their organisations strategically engaging in post-2015 negotiations on a number of fronts. Direct advocacy approaches included providing submissions not only to the global thematic consultation on health in 2012, but also to the ten other UN-led Global Thematic Consultations on the Post-2015 Development Agenda. In inter-sectoral forums, these submissions served as part of broader strategic awareness-raising initiatives, underlining the interconnectedness of sexual and reproductive health and rights. Coalitions with other stakeholder groups were also formed, and targeted research articles and briefs were published by agencies such as the Overseas Development Institute and the Population and Sustainability Network (Iv1566) to build the evidence base for sexual and reproductive health and rights.

Other approaches included working up investment cases and developing sexual and reproductive health and rights-related metrics for country consideration: “The measurement element of the new framework… can [influence] whether some issues are included or omitted.” (Iv1553) More subtle advocacy efforts ranged from engaging in “discrete, bilateral high-level outreach” (Iv1566) to identifying key country negotiators in the Open Working Group for future lobbying. Strategic plans to combine the content of ICPD+20 meetings in 2014 with post-2015 development goal momentum were also highlighted: “We have been working since the ICPD review began very closely… to make linkages and see that these issues work together and are treated together.” (Iv1552)

Positioning in the High-Level Panel’s report

“It’s a good first start.”

Many of the 19 participants praised the High-Level Panel for unambiguously positioning sexual and reproductive health and rights as one of the five indicators under the Ensure Healthy Lives goal: “So there’s a bold vision when it comes to that.” (Iv1553) Inclusion of the goal to empower girls and women to achieve gender equality was also lauded as “a good first start into getting something solid on women’s rights and gender equality into the new framework”. (Iv1553) However, others felt the High-Level Panel did not go far enough and specify the multi-sectoral nature of the relationship between sexual and reproductive health education and the “critical importance in today’s world of comprehensive sexual education”, (Iv1566) and in the other illustrative goals and targets, “… because if you see all the consultations, young people, women, really are reflecting the importance of health, particularly sexual and reproductive health”. (Iv1552)

The prominence of sexual and reproductive health was not astonishing. Several participants were “not that surprised” (Iv1579) sexual and reproductive health and rights got such direct and strong representation within the High-Level Panel’s Report, or that the global health community were generally pleased with the Report’s health issue coverage for two reasons. First, the comprehensive nature of the health issues included in the High-Level Panel’s Report did not allow for fractionalisation in the global health community to emerge at this early negotiation phase:

“I haven’t seen anything where it sounds like people have erupted over fault lines in turf… there’s not a whole lot to fight over if everyone’s got their issue in the [High-Level Panel’s] framework: WHO has got their thing, the UN has got their thing, UNFPA, UNICEF, everyone’s got their thing in there right now… Right now, I don’t think anyone feels threatened by other people’s issues.” (Iv1587)

Second, there was broad consensus among the 57 participants that the first phase of UN-led post-2015 discussion was not where the real “horse-trading in the negotiations” (Iv1553) will occur. Rather, the High-Level Panel report was referred to as “the icebreaker” (Iv1561) and “the shot across the bow”, (Iv1556) until the second phase of post-2015 negotiations.Footnote* One participant from a government agency quoted Churchill: “It’s not the beginning of the end; it’s the end of the beginning.” (Iv1561)

“Right now… we are holding our breath… The full phraseology of universal access to sexual and reproductive health and rights really is one of the biggest asks of the global community if we’re going to move beyond what was already there the last 20 years.” (Iv1556)

Early prominence is no guarantee

“It’s a very fluid process.”

The majority of participants predicted the second phase of post-2015 negotiations would follow the UN Secretary-General’s report to the UN General Assembly in September 2013, which would mark a shift from a UN- to a Member State-driven process. Among the 19 participants who commented on sexual and reproductive health and rights in the post-2015 context, there was strong agreement that this shift will have the most impact on whether the elevation of sexual and reproductive health and rights would survive in the final document:

“In the end, the decision is for Member States to make… So far it’s a very fluid process… It’s really incumbent on Member States who, in the end, will decide on what the goals will be, what the targets will be, and how they will be shaped.” (Iv1553)

For one participant, it was important to recognise that Member States were eager to assert their ownership. This participant contended that the inter-governmental process may not in fact place much weight at all on the High-Level Panel’s offerings:

“It’s not a report that’s been consulted with Member States. They didn’t have any input into it… So that’s a political factor to keep in mind.” (Iv1554)

What’s coming down the line

“There is going to be the most almighty fight about reproductive health.”

Many of the 19 participants anticipated that the politicisation of sexual and reproductive health and rights would become a major fault line in the post-2015 global decision-making process.

“Talking to my colleagues in New York the other day, they say that whilst it’s been going well you can see where the cracks are going to open and they’ll be on the things where the cracks always open, irrespective of the issue in the General Assembly: on resource transfers, on sexual and reproductive health, on intellectual property, those ones particularly… Your client is the European Union, right — who can’t even make up their own minds about some of those issues, and particularly the sexual and reproductive rights.” (Iv1575)

“…We know there is going to be the most almighty fight about reproductive health…” (Iv1579)

For one UN respondent, the politicised nature of sexual and reproductive health and rights underscored countries’ early reticence to “show their cards” at the post-2015 negotiation table, anxious not to compromise their negotiating positions:

“Member States don’t feel like they’re in a position yet to make specific commitments because their specific commitments are going to be very contingent on how gender plays itself out, how inequality plays itself out.” (Iv1584)

Two other UN participants expressly referred to interlinked socio-cultural/religious issues traditionally politicising (and polarizing) sexual and reproductive health and rights (mainly at a country-level) as the reason why sexual and reproductive health and rights would ultimately be challenged in the inter-governmental negotiations: “There will be a lot of cultural and religious issues… This will be a very difficult discussion… [for] Muslim countries, and even the Vatican.” (Iv1583) One participant noted that the Catholic Church’s post-2015 positioning would be crucial and that Pope Francis had expressed: “interesting perspectives on poverty”, expressing hope for the possibility of change as regards sexual and reproductive health and women’s rights. (Iv1552)Footnote*

National electoral cycles and populist politics around sexual and reproductive health and rights and women’s rights more broadly, were expected to impact on individual countries’ positioning:

“Some countries are changing some positions [on sexual and reproductive health and rights], particularly countries that are going through an election soon… I mean countries that perhaps now, they feel a little bit not so comfortable to support certain issues because their position will be seen as them introducing Western culture, etc.” (Iv1552)

Adding to the “many other factors” influencing country sensitivity on the topic of sexual and reproductive health and rights are the global power differentials that are implicitly involved, with the shadow of population control likely to be evoked in debates around sustainable development:

“It’s also sensitive because of the whole thing that the rich try to tell the poor to reduce the number of children for the ecological footprint, but that’s not the key element. The key element is rights and access to family planning.” (Iv1579)

Aligning sexual and reproductive health and rights and the sustainable development agenda

Despite finding widespread concern among participants on how sexual and reproductive health and rights will fare in Member State negotiations, we also found a sense of optimism. Several UN-based participants observed that countries in earlier Sustainable Development Goal meetings had raised sexual and reproductive health and rights as an in-country development priority. For them, it is such countries that will bring sexual and reproductive health and rights as an issue “to the table”, (Iv1579) advocating for its inclusion in the post-2015 spotlight. The Nordic and European countries were described as “always… supportive and… vocal in these discussions”. (Iv1582)

The women’s rights agenda, incorporating sexual and reproductive health and rights, was also seen to be inextricably linked to the Sustainable Development Goal agenda:

“From a women’s rights perspective, it’s the right to have access to family planning and so on that was already signed by all countries in ’94 during the ICPD, but not implemented… There are 220 million women who would like to avoid pregnancy, and who don’t have access to family planning methods. The goal of Family Planning 2020 is to reduce that to 110 million. So that should be taken into the equation in the discussion about resources, the planet. And that’s why reproductive health is so important.” (Iv1579)

However, there was acknowledgement of the inherent sensitivity in making the link between sexual and reproductive health and rights and the sustainable development agenda:

“Nobody wants to work on the China model, reducing the population because of the environment. And who is responsible for the high CO2 emissions and ecological footprints? It is definitely not those countries who are [producing] a lot of children. Not yet, I mean.” (Iv1579)

“The first draft that was put out for consultation… of the Sachs report was extremely alarming. They have these explicit targets to reduce fertility and population growth as a proposal… that is completely unacceptable after the 1994 ICPD Programme of Action… It’s a bit mollified in the final version but there’s a very clear slant on the demographic, population control implications… There is concern that with the environmental agenda, the reproductive rights agenda could be sacrificed or at risk and erode what was in the Cairo agreement of ’94… So those are some flags many of those analysing this process are concerned about; so the absolute necessity is to insist in every step and every debate on the human rights of women, especially their sexual and reproductive health and rights at the centre of any population/sustainable development agenda.” (Iv1566)

In addition to the above cautionary approach, there was outright concern that the sustainable development agenda would not adequately focus on redressing the pervasive breaches of the sexual and reproductive health and rights of women and girls, and of some of the most vulnerable and marginalised populations:

“I’m sure the Sustainable Development Goals will… be what the post-2015 agenda is about… but I have no trust at all this is going to be implemented in… the least developed countries and conflict and fragile states contexts… [MDG achievement is] very late in these countries and I am worried that under this paradigm we are even more late.” (Iv1571)

This point, often lost in the rush to table visionary goals, reinforces both that successfully achieving sexual and reproductive health and rights – in all country contexts – is integral to sustainable development and that sexual and reproductive health and rights advocates need to be advocating beyond the usual forums, and in so doing, continue to focus on “very poor countries, women, country contexts, sexual violence, again all these major public health problems that belong to these areas, but also to other areas, together with new issues of urbanisation and modern life…”. (Iv1571)

Discussion and conclusions

This paper reports the views of participants from the multilateral and related agencies on the strategic location of sexual and reproductive health and rights in the evolving global negotiations on the post-2015 sustainable development agenda. Documenting their positions immediately after the release of the High-Level Panel report in mid-2013 is particularly salient. There is a parallel between the sense of optimism among these participants as regards the final post-2015 outcome document, and a similar, misplaced confidence among advocates in 1999–2000 with the MDG agenda. The occurrence of the ICPD Beyond 2014 event this year eerily mirrors the timing of the ICPD+5 Review prior to the formulation of the MDGs.

The parallels are a necessary framing for current strategy: history would suggest that sexual and reproductive health and rights advocates – more than ever – must exercise caution over optimism. Sexual and reproductive health and rights may have secured a supportive consensus within the multilaterals in early post-2015 negotiations, in a process that has been both inclusive and transparent, but there is still 18 months of complex global discussion to go. Moreover, the final decision will not be made by the multilaterals but by Member States, even though the UN machine will undoubtedly seek to influence the content of the final outcome document. Given Member State diversity, it is unsurprising that many participants consider there is a real risk sexual and reproductive health and rights could lose out when Member States try to reach consensus.

The tapestry of Member States negotiating development goals (and the merger of two parallel post-2015 processes – on poverty and the environment) could make this decision-making process far more complex than the last, compounded by the diversity of influential actors on the world stage (from big banks and multinational corporations, to powerful philanthropic organisations and advocacy coalitions, to religious orders) that seek to wield their considerable economic and political influence.Citation5 Consequently, in a world still reeling from the shockwaves of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, the potential for the post-2015 outcome document not to be grounded in a fundamental health and human rights framework is very real, as is the “watering down” of any transformative, visionary, post-2015 goals. For sexual and reproductive health and rights advocates, these multiple challenges are heightened by the predicted intense opposition to sexual and reproductive health and rights, and the “much older and more intractable prejudice and fear directed at women’s and girls’ empowerment in all its forms”.Citation11

The interviews document the political astuteness of sexual and reproductive health and rights advocates in their engagement in the post-2015 discussion in 2013, and their collective determination that history would not repeat itself. Their commitment and perspicacity will need to be channelled into ongoing, tactical advocacy with Member States, with a strong multisectoral focus, at all times promoting the interconnectedness of sexual and reproductive health and rights and the sustainable development agenda. Furthermore, sexual and reproductive health and rights advocates must vigorously ensure this relationship is not translated by Member States into a population deficit approach that in fact undermines the sexual and reproductive health and rights agenda.

The critical role of civil society, and their continued support for sexual and reproductive health and rights, will be crucial in advocacy at both global and national levels. In the shifting sands of post-2015 negotiations, sexual and reproductive health and rights advocates must also ensure that the sexual and reproductive health and rights of those in the least developed countries, and in fragile and conflict contexts, remain in focus.Citation25 Tactics include avoiding introducing any language that is not already accepted in the existing documents, ensuring that sexual and reproductive health are not at risk of regressive outcomes from further debate. Another is that advocates explore alternative ways of framing the positioning of sensitive issues, e.g. without overtly using the word “rights”’. No doubt these and other responses will precipitate both support and opposition.

A further challenge for civil society advocates is that the World Health Organization is heavily promoting an overarching goal for health of universal health coverage (UHC) among Member States. Many civil society advocates are not proponents of UHC as an overarching goal, which they fear may be used to sideline sexual and reproductive health and rights; some think a health goal nested in improving the health and well-being of populations throughout the lifespan would be more optimal. Others have called for the right to the highest attainable standard of health to be the goal.Citation1

Lastly, sexual and reproductive health and rights advocates must continually critically examine the evolution of the post-2015 discourse (multi-sectoral literature, international and national reports, meetings, conferences) and reappraise their strategies. The Lancet’s push for a post-2015 “Grand Convergence”, for example, supports broad structural change in health systems that will enhance efforts to reduce maternal mortality, but falls short of explicitly proposing to embed sexual and reproductive health and rights into the post-2015 health and development goal agenda.Citation26 For sexual and reproductive health and rights advocates, the next 18 months will certainly be no “doddle”.

Acknowledgements

Funding for Go4Health was from the European Union’s 7th Framework Programme (HEALTH-F1-2012-305240) and the Australian Government’s NH&MR–EU Collaborative Research Grants (1055138).

Notes

* The first phase of post-2015 negotiations was led by the UN in 2012 through its country consultations (some of which are still ongoing) and 11 Global Thematic Consultations, culminating in the High-Level Panel report of May 2013 and the General Assembly Meeting on the MDGs and post-2015 agenda in September 2013.

* Goal 2 Achieve Development Within Planetary Boundaries (Target 2C: Rapid voluntary reduction of fertility through the realization of SRHR in countries with total fertility rates above three children per woman and a continuation of voluntary fertility reductions in countries where total fertility rates are above replacement level).

† Goal 5 Achieve Health and Well-being at all Ages (Target 5A: Ensure universal access to primary health care that includes sexual and reproductive health care…).

** The drafters of the MDGs were a select cluster of technocrats from UN and other multilateral agencies, mainly the International Monetary Fund, World Bank, and Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee (OECD-DAC).

* Although the Sustainable Development Solution Network’s report had also been released during the period of our interviews, the 57 participants referred to its contents far less.

* Two weeks after this interview the Holy See made its first comment against including sexual and reproductive health and women’s rights. See: http://www.holyseemission.org/statements/statement.aspx?id=434

References

- M Berer. A new development paradigm post-2015, a comprehensive goal for health that includes sexual and reproductive health and rights, and another for gender equality. Reproductive Health Matters. 21(42): 2013; 4–12.

- UN Secretary-General’s High-Level Panel of Eminent Persons on the Post-2015 Development Agenda. 2013. http://www.post2015hlp.org

- Sustainable Development Solutions Network. http://unsdsn.org

- M Haslegrave. Ensuring the inclusion of sexual and reproductive health and rights under a sustainable development goal on health in the post-2015 human rights framework for development. Reproductive Health Matters. 21(42): 2013; 61–73.

- PS Hill, D Huntington, R Dodd. From Millennium Development Goals to post-2015 sustainable development: sexual and reproductive health and rights in an evolving aid environment. Reproductive Health Matters. 21(42): 2013; 113–124.

- ST Fried, A Khurshid, D Tarlton. Universal health coverage: necessary but not sufficient. Reproductive Health Matters. 21(42): 2013; 50–60.

- D Hulme. The Making of the Millennium Development Goals: Human Development Meets Results-based Management in an Imperfect World. 2007; University of Manchester Brooks World Poverty Institute: Manchester.

- J Vandermoortele. The MDG story: intention denied. Development and Change. 42(1): 2011; 1–21.

- C Barton, M Khor, N Narain. Civil Society Perspectives on the Millennium Development Goals. United Nations Development Programme; 2005. http://www.undp.org/content/dam/aplaws/publication/en/publications/poverty-reduction/poverty-website/civil-society-perspectives-on-the-mdgs/Civil%20Society%20Perspectives%20on%20the%20MDGs.pdf

- Ortega A Ortiz. Perpetuating power: a response. Reproductive Health Matters. 19(38): 2011; 35–41.

- N Sadik. Sexual and reproductive health and rights: the next 20 years. Reproductive Health Matters. 21(42): 2013; 13–17.

- N Kabeer. The Beijing Platform for Action and the Millennium Development Goals: Different processes, different outcomes. UN Division for the Advancement of Women Expert Group Meeting – Achievements, gaps and challenges in linking the implementation of the Beijing Platform for Action and the Millennium Declaration and Millennium Development Goals. EGM/BPFA-MD-MDG/2005/EP.11; 2005. http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/egm/bpfamd2005/experts-papers/EGM-BPFA-MD-MDG-2005-EP.11.pdf

- Task Team. Health in the Post-2015 Development Agenda: Report of the Global Thematic Consultation on Health; 2013. www.worldwewant2015.org/health

- Task Team. New partnerships to implement a post-2015 development agenda (Discussion note), 2012. http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/pdf/global_partnerships_Aug.pdf

- JD Sachs. From Millennium Development Goals to Sustainable Development Goals. Lancet. 379(9832): 2012; 2206–2211.

- M Sandelowski. Time and qualitative research. Research in Nursing and Health. 22(1): 1999; 79–87.

- JR Kelly, JE MGrath. On Time and Method. 1988; Sage: Newbury Park, CA.

- H Starks, Trinidad S Brown. Choose your method: a comparison of phenomenology, discourse analysis, and grounded theory. Qualitative Health Research. 17(10): 2007; 1372–1380.

- J Cheek. At the margins? discourse analysis and qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research. 14(8): 2004; 1140–1150.

- J Milliken. The study of discourse in international relations: a critique of research and methods. European Journal of International Relations. 5(2): 1999; 225–254.

- D Lupton. Discourse analysis: a new methodology for understanding the ideologies of health and illness. Australian Journal of Public Health. 16(2): 1992; 145–150.

- AJ Onwuegbuzie, NL Leech. A call for qualitative power analyses. Quality and Quantity. 1(1): 2007; 105–121.

- N Mays, C Pope. Rigour and qualitative research. British Medical Journal. 311(6997): 1995; 109–112.

- J Attride-Stirling. Thematic networks: an analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research. 1(3): 2001; 385–405.

- K Higgins. Reflecting on the MDGs Paper of the North-South Institute and Making Sense of the Post-2015 Development Agenda. 2013; North-South Institute: Ottawa.

- Grand convergence: a future sustainable development goal [Editorial]? Lancet 2014;383(9913):187.