Abstract

Small-scale pilot projects have demonstrated that integrated population, health and environment approaches can address the needs and rights of vulnerable communities. However, these and other types of health and development projects have rarely gone on to influence larger policy and programme development. ExpandNet, a network of health professionals working on scaling up, argues this is because projects are often not designed with future sustainability and scaling up in mind. Developing and implementing sustainable interventions that can be applied on a larger scale requires a different mindset and new approaches to small-scale/pilot testing. This paper shows how this new approach is being applied and the initial lessons from its use in the Health of People and Environment in the Lake Victoria Basin Project currently underway in Uganda and Kenya. Specific lessons that are emerging are: 1) ongoing, meaningful stakeholder engagement has significantly shaped the design and implementation, 2) multi-sectoral projects are complex and striving for simplicity in the interventins is challenging, and 3) projects that address a sharply felt need experience substantial pressure for scale up, even before their effectiveness is established. Implicit in this paper is the recommendation that other projects would also benefit from applying a scale-up perspective from the outset.

Résumé

Des projets pilotes à petite échelle ont démontré que des approches qui intègrent les questions de population, de santé et d’environnement peuvent répondre aux besoins et aux droits des communautés vulnérables. Pourtant, ces projets et d’autres types de projets de santé et développement ont rarement influencé l’élaboration de politiques et programmes plus larges. ExpandNet, un réseau de professionnels de santé qui s’emploient à étendre les projets, avance que c’est parce que les projets sont rarement conçus en gardant à l’esprit la viabilité et l’expansion futures. Pour préparer et réaliser des interventions durables pouvant être appliquées à une plus grande échelle, il faut une mentalité différente et de nouvelles approches des tests pilotes/à petit échelle. Cet article montre comment cette nouvelle approche est appliquée et les leçons initiales de son utilisation dans le projet sur la santé de la population et l’environnement dans le bassin du lac Victoria actuellement mené en Ouganda et au Kenya. Les leçons spécifiques qui émergent sont les suivantes : 1) l’engagement concret et suivi des acteurs a sensiblement façonné la conception et l’application, 2) les projets multisectoriels sont complexes et la recherche de simplicité dans les interventions est difficile, et 3) les projets qui répondent à un besoin profondément ressenti subissent des pressions les poussant à s’étendre, avant même que leur efficacité soit avérée. La recommandation selon laquelle d’autres projets bénéficieraient aussi de l’application d’emblée d’une perspective de mise à l’échelle est implicite dans l’article.

Resumen

Proyectos piloto en pequeña escala han demostrado que mediante enfoques integrados de población, salud y medio ambiente se puede atender las necesidades y los derechos de las comunidades vulnerables. Sin embargo, estos y otros tipos de proyectos de salud y desarrollo rara vez influyen en la formulación de políticas y programas más amplios. ExpandNet, una red de profesionales de salud que trabajan en ampliación, argumenta que esto se debe a que los proyectos generalmente no son diseñados con futura sostenibilidad y ampliación en mente. La creación y ejecución de intervenciones sostenibles, que puedan aplicarse en mayor escala, requiere una mentalidad diferente y nuevos enfoques con relación a pruebas piloto en pequeña escala. En este artículo se muestra la aplicación de este nuevo enfoque y las lecciones iniciales de su uso en el Proyecto Salud de las Personas y el Medio Ambiente en la Cuenca del Lago Victoria, actualmente en curso en Uganda y Kenia. Las lecciones específicas que están surgiendo son: 1) la participación significativa y continua de partes interesadas ha influido considerablemente en el diseño y la ejecución; 2) los proyectos multisectoriales son complejos y es un reto lograr simplicidad en las intervenciones; y 3) los proyectos que abordan una necesidad muy sentida experimentan considerable presión para ampliación, aun antes de establecida su eficacia. Este artículo presenta la recomendación implícita de que otros proyectos también se beneficiarían de aplicar una perspectiva de ampliación desde el principio.

Over the past few decades small-scale, community-based efforts to simultaneously address population issues, public health concerns, environmental conservation and sustainable livelihoods have been undertaken in different corners of the world. Such integrated population, health and environment (PHE) approaches are now enjoying renewed attention. A major conclusion of the 2011 Population Footprints conference was that “the inter-connectedness of our multiple grand challenges demands similarly inter-connected responses… There is no silver bullet – just millions of right actions.”Citation1 Efforts to undertake the “right actions” have largely taken place in the context of organizing small-scale pilot projects that address the PHE needs and rights of communities in an integrated manner. These projects have proven that integrated approaches can have multiple benefits. For example, some have encouraged men to become more engaged in family planning and women to be more active in natural resource management.Citation2 However, while they have improved conditions for some communities, they have yet to reach their potential to influence larger national policy and programme development.Citation3Footnote*

Developing and implementing interventions that are sustainable and can be expanded on a larger scale requires a different mindset and new approaches to small-scale pilot testing. If future expansion is the goal, then projects must plan for, and set the right levers in place from the outset to enable that possibility.Citation4 This paper describes such an approach and the initial lessons that have been learned in the process of applying it to the Health of People and Environment in the Lake Victoria Basin (HoPE-LVB) Project – a PHE project underway in East Africa. The HoPE-LVB team is learning much about how to work within this new paradigm and wishes to share some of the key findings, even while the project is ongoing, so that those working on integrated PHE projects and in other areas of health and development can learn from this experience.

Background

The new paradigm for developing, testing and expanding interventions that is discussed here was developed by ExpandNet, a global network of public health professionals who seek to advance the practice and science of scaling up. This network, created in 2003, grew out of the WHO-sponsored Strategic Approach for Strengthening Reproductive Health Policies and Programmes, a three-stage process that more than 35 countries have used to identify priority country needs, conduct action research to test potential solutions and give focused attention to scaling up of successful interventions. When the country projects which originally pioneered this approach in the 1990s were completing the testing of interventions, it became clear that systematic approaches to scaling up were lacking and that guidance was needed. In collaboration with multiple Strategic Approach partners, ExpandNet and WHO thus began a sustained program of work consisting of literature reviews and the development of a framework, scaling-up case studies,Citation5 a practical guidance documentCitation6 and a tool for developing a scaling-up strategy.Citation7

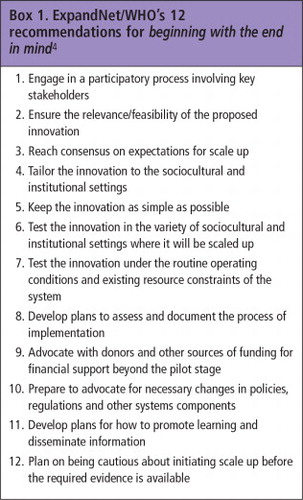

In applying the latter tool, entitled “Nine steps for developing a scaling-up strategy”, Citation7 in different settings, ExpandNet/WHO facilitators frequently heard comments from team members like: “We wish we had taken these considerations into account when we initially began our project instead of now, at the end, when we are strategizing about scale up”. This led to the development of a tool entitled “Beginning with the end in mind: Planning pilot projects and other programmatic research for successful scaling up”, Citation4 which provides 12 recommendations to help ensure that a sustainable and scalable model is designed and tested, laying the groundwork for future success with scaling up.

The HoPE-LVB Project is the first to systematically apply this tool. The HoPE-LVB Project goal is to reduce threats to biodiversity conservation and ecosystem degradation in the Lake Victoria Basin, while simultaneously increasing access to family planning and maternal, child, sexual and reproductive health services from a rights-based perspective. The overarching strategic objective is to develop and test a scalable model for building capacity and promoting an integrated set of population, health and environment interventions that can be adopted by Ugandan and Kenyan communities, and local, national and regional governments.

Project sites are in two sub-counties in two districts in Uganda and three sub-counties in one county in Kenya. The project is being implemented in close collaboration with existing community-based groups, including women’s groups, youth groups, farmers’ groups, young mothers’ clubs, beach management units and both health facility- and community-based health care providers. Interventions include upgrading the skills of service providers from health, agriculture, animal husbandry and fisheries sectors, conducting PHE-integrated community dialogues, outreach and door-to-door education and services, and supporting the establishment of PHE-village committees. In addition, together with communities, the project has identified and is supporting model households willing to demonstrate PHE-oriented lifestyles and approaches, and share their knowledge and skills within their communities and outside. The project also has a major focus on advocacy with district, county and national level technical personnel and policymakers in the three sectors of population, health and the environment.

Methods

The authors of this paper are the leaders and organizers of the HoPE-LVB Project and the authors of the ExpandNet/WHO Beginning with the end in mind toolCitation4 who have been providing technical support to the HoPE-LVB team in the application of the ExpandNet/WHO tools since late 2011. The experiences discussed here represent the authors’ reflections as participant observers in the process, and are informed by analysis of results from systematic baseline research, which included a participatory rural appraisal in project sites; PHE-related policy analysis based on key informant interviews; a desk review of planning and operational documents from the community, district, national and regional levels; and an analysis of preliminary results from systematic in-depth interviews with nine project team members and 13 project stakeholders in the context of a mid-term review, underway at this writing.Footnote* ExpandNet facilitators have made six visits to the project, and the authors worked via electronic distance communication during the intervening periods.

What can be expected from pilot projectsFootnote†

When done well, pilot projects can be a sound approach to programme development. It is more cost-effective to test new approaches and identify and correct bottlenecks in a few locations rather than begin implementation in an entire system, only to realize later that interventions are not feasible, acceptable or effective.Citation8 However, governments around the world have grown weary of pilot projects because they are often unable to generate the desired impact on policy and programme development.Citation9–11

There is increasing recognition that one major reason why pilots cannot be expected to have large-scale, sustainable impact is because, as “proof of concept” studies, they require special resources and support to ensure proper implementation during testing, which subsequently cannot be replicated on a larger scale.Citation12,13 Moreover, there has been a tendency to set up parallel structures in cases where the existing system is not functioning well, rather than undertaking system strengthening as a key component of the intervention. Awareness is growing that in order to learn whether and how interventions can be successfully scaled up, they must be tested with the people and in the systems that will be responsible for them, thereby providing “proof of implementation”.

ExpandNet’s response to the pilot conundrum

The 12 recommendations in , while seemingly self-evident, taken together represent a departure from prevailing approaches to project design and implementation. For example, while other projects might use participatory approaches involving key stakeholders (No.1), this may not always include the intended or potential future users of the innovation. Advice from stakeholders is essential to ensure the relevance and feasibility of proposed interventions (No.2). Interventions must not only promise to have significant impact if implemented, but the feasibility of implementing them within the institutions that will be responsible for them on a large scale must be assessed. Advice is not always sought for how to develop appropriate mechanisms through which new interventions can be embedded within existing systems, and agreement is often not reached on what are realistic expectations for future scale up (No.3).

Box 1 ExpandNet/WHO’s 12 recommendations for beginning with the end in mind.Citation4

Proof of implementation requires tailoring interventions to the socio-cultural and institutional settings, testing them in the settings where they will be scaled up and working – to the extent possible – within routine operating conditions and resource constraints (No.4,6,7). In other words, doing precisely what pilot projects often do not seek to do because researchers and others responsible for their design may not be inclined to embed the project in a system that has major capacity and monitoring challenges. ExpandNet argues, however, that such proof of implementation is precisely what is needed if one hopes to test an innovation that can be scaled up by and within that system (No.6,7).

One of the most widely agreed upon but most difficult recommendations is to keep interventions as simple as possible (No.5). Beginning with scaling up in mind requires avoiding complexity where it can be avoided and recognizing that a complex package of interventions is likely to be more difficult to scale up and take more time to achieve.

Sustainable scale up requires not only expanding a successfully tested package of interventions to new areas, but also institutionalizing interventions in policies, regulations, operational procedures, information systems and budgets. This process should start not only when pilots are completed, but early on (No.10). The same is true for advocacy with donors for funding beyond the pilot stage (No.9). In fact, the discontinuation of funding at the successful conclusion of a proof of concept study is one of the major reasons why the transition to scaling up often does not occur. Assessing and documenting the lessons that emerge in the process of implementing pilot interventions and disseminating the learning (No.8, 11) are essential to build the case for large-scale expansion, institutionalization and the necessary financial support.

Finally, an important aspect to keep in mind from the outset is that overly rapid scale up, and especially initiating scale up before the evidence exists that supports expansion, should be avoided (No.12). However, resisting the pressure to scale up prematurely is difficult in the face of community, government or donor pressure in light of the urgent need for interventions.

That these are not easy tasks should be clear from this brief review of ExpandNet’s recommendations for beginning pilot projects with sustainable scale up in mind. There are no quick fixes but, as will become apparent from the experience of the HoPE-LVB Project, beginning with the end in mind is well worth the effort.

How the HoPE-LVB Project is working with the end of scaling up in mind

A group of three donors who had previously supported projects focused on scaling up and on PHE came together to fund a PHE project in the Lake Victoria Basin region of East Africa. Previously funded PHE projects faced challenges of sustainability, and few reached beyond the confines of their original target communities. The donors encouraged ExpandNet’s participation in the conceptualization and implementation of the new project because they wanted it to be explicitly focused on future scale up. The HoPE-LVB Project was subsequently awarded to Pathfinder International and two local non-governmental environmental conservation organizations working around Lake Victoria in Uganda and Kenya – the Ecological Christian Organization (ECO) and OXIENALA (Friends of Lake Victoria). Representatives of these groups serve as the core project implementation team.

To support the project team to begin internalizing knowledge about scaling up, early on facilitators began by discussing the ExpandNet scaling-up framework and key lessons from global experience and diverse literature about the determinants of scaling-up success. The goal was to ensure that interventions and their implementation would take these determinants into account, thereby ensuring the possibility of later adoption by a variety of stakeholders from local to regional level. The project also began an ongoing process of analysing project implementation with regard to the 12 recommendations of Beginning with the end in mind. Citation4 As a result, a subtle shift occurred in the team’s thinking and in the way the project was operationalized. For example, rather than setting up parallel structures, the team has tried to work with, and within, existing personnel and systems.

Engaging in a participatory process with key stakeholders

During the first months, the team conducted multiple group and individual interviews with a variety of community-based groups, to gather perspectives about whether the proposed interventions were relevant to their settings and how to ensure successful implementation. Interviews gave the team insight into areas where community members’ knowledge and capacity could be mobilized. For example, members of the beach management units explained how overfishing was affecting daily fish catch. They showed the team the breeding areas that required increased protection and provided ideas about how, with additional resources, they could participate more actively in their protection. Members of existing women’s and youth groups described challenges in accessing family planning and other reproductive, maternal and child health services. The concerns articulated by project communities were used to shape which and how project interventions would be implemented.

The team also met with senior national-level officials representing relevant Ugandan and Kenyan line ministries from population, health and the environment, as well as East African regional entities such as the Lake Victoria Basin Commission – a political and technical regional platform influencing policies in the five Basin countries. The response at these meetings was always positive. Some stakeholders saw the project as an “eye-opener” for practical ways to integrate the population dimension with issues such as deforestation, water and sanitation challenges, unsustainable land use, and overfishing, and in promoting new approaches at the community level. The meetings provided recommendations for how to proceed in ways that would ensure the relevance of proposed interventions. For example, the Kenya Ministry of Health urged the project to utilize government materials, curricula, trainers and workers instead of creating new cadres or structures that would be irrelevant in the future. Government officials have said that since this guidance has been followed, they have greater confidence that HoPE-LVB interventions could be replicated elsewhere in the future.

These early meetings also served to gain commitment to the project. One result has been increased funding in the form of a grant from USAID East Africa to the Lake Victoria Basin Commission to work on PHE at the regional level, including collaborating with HoPE-LVB. These contacts created opportunities to showcase achievements at a number of high-level events, including meetings of the Kenya National PHE Network, Uganda PHE Working Group, Lake Victoria Basin Commission, 7th Best Practices Forum of the East/Central/Southern African Health Community, Ethiopia PHE Consortium, PHE Symposium at the 4th East African Community’s Annual Health and Scientific Conference, and the 2013 International PHE Conference.

As the project progressed, the dialogue with key stakeholders continued via the establishment of multi-sectoral steering committees in both countries, comprised of representatives of the line ministries, district officials representing health and the environment, NGOs, universities and others. Members provide strategic direction and technical input to project activities to help meet the goal of developing a sustainable, scalable integrated PHE model from their particular sectoral perspectives. In addition, understanding and commitment is growing for them to play a key role in facilitating the uptake of successfully tested interventions within their own organizations and by partners. In Kenya, the project has helped facilitate the creation of local PHE village committees and a county-level PHE steering committee to address PHE county-wide and to link to the national PHE network. Such participation is laying the groundwork for future expansion of tested interventions within the county.

While this approach has helped the project greatly, one lesson learned is that enabling meaningful participation can have significant cost and time implications. These are not typically planned for in pilots. The team continues to grapple with striking the right balance of engagement with stakeholders at the various levels and selecting who, from the large set of interested parties, should participate and when. Another lesson is that when an innovation addresses sharply felt needs of stakeholders, pressure mounts to begin the scaling-up process even before evidence of success is available.

Ensure the relevance and feasibility of the proposed innovationFootnote*

Following the early, intensive assessment, the team analysed the initially proposed interventions in light of stakeholder input and the determinants of scaling-up success. A few interventions were eliminated as beyond the capacity of the project to implement successfully; others were simplified or re-conceptualized. For example a planned intervention to support women’s groups to produce rope from the invasive water hyacinth, and identify the necessary market linkages to ensure its viability, was dropped. While this intervention addressed important community livelihood needs and environmental concerns, continued dialogue with community members revealed that production was labour-intensive and the product too expensive for local markets, rendering the intervention neither cost-effective nor feasible — nor scalable.

Tailor the innovation to the sociocultural and institutional settings

The team learned a major lesson about how interventions could be tailored to local institutional settings when plans for building capacity at the community level to implement agro-forestry practicesFootnote* were discussed. Initially, project personnel planned to provide training directly to community-level trainees; however, through analysis they realized the importance of involving government representatives whose task was to implement similar initiatives. Examples included the existing but largely inactive village environmental committees, sub-county council members working on environmental issues, and district environmental and natural resource officers. The idea was to convert the innovation from a simple local training function into a “training of trainers” who would be in a position to expand the application of new knowledge beyond the initial project sites. Such collaboration provided an opportunity to raise awareness about health and population issues and integrated approaches for environmentally-focused workers. It also served to start the process of institutionalizing activities and building capacity in the government structures that could take responsibility for replicating these activities in the future.

Existing institutional challenges can prove insurmountable for a small project, and intermediate solutions need to be identified. Such was the case with the contraceptive supply chain, in that it was not possible to change government systems that were not adequately addressing demand in project sites. The team had to develop innovative ways to supply the needed contraceptives outside of the routine system, while recognizing that concurrent advocacy for improved Ministry of Health commodity supply and distribution mechanisms was essential. The team’s participation in district health management team meetings and national level working groups provide opportunities to advocate for needed change.

Keep the innovation as simple as possible

Although simple innovations are easier to scale up, this is particularly challenging for PHE projects, because community needs are not sector-specific and yet working across multiple sectors is complex in that: 1) it requires a departure from predominant vertical approaches; and 2) disincentives can discourage cross-sectoral collaboration.

For example, district level reproductive health officers do not normally address environmental conservation in their work, and before this project were not inclined to educate lower level health care providers about the connection between growing populations and pressure on natural resources like fish stocks or firewood. Helping people work in new areas takes time, new patterns of work, and sufficient orientation, but in the long run it is perceived to have multiple benefits which can sustain innovations. A lesson for the team has been that working concurrently on population, health and the environment will have implications for how rapidly expansion to new areas can proceed.

The team also struggled to pare down the number of interventions and to reduce each to its most essential components. An example was the need to reduce health care provider training time to the minimum allowed by Ministry of Health certification requirements and ensuring providers were also trained in integrated PHE concepts. This was a challenge for Ministry trainers, but in the end yielded a simplified model curriculum that was both acceptable to the Ministry and would remove providers from their facilities for less time.

Prepare to advocate for expansion and institutionalization

From the outset, the project had dedicated funding earmarked for strategic advocacy and has engaged stakeholders at the community, sub-county, district/county, national and even regional levels. Advocacy activities have helped to raise the profile of the project and PHE more generally, and are helping to pave the way for sustainability, future expansion and institutionalization. Project personnel participate in meetings of sub-county councils, district health management teams, national level health working groups, and more. PHE champions have been formally identified and trained at varying levels to advocate for expansion of PHE and HoPE-LVB approaches.

In the constantly changing political environment of Kenya’s governmental devolution process, the team is attempting to embed a PHE perspective in new administrative structures. Efforts are also underway to disseminate HoPE-LVB approaches and preliminary findings via district, national and international meetings and conferences where targeted decision-makers are in attendance. Media personnel are being oriented in both countries so they can support dissemination of the project experience and PHE approaches more generally. In some cases such advocacy has made it possible to overcome policy obstacles to project interventions. For example, in Kenya, where initially only community health workers were allowed to refer patients to health facilities, through the project’s advocacy efforts other community group members have been approved by the Ministry of Health to make referrals for family planning and maternal and child health services.

Cross-sectoral collaboration is emphasized in a range of policies throughout East Africa. This provides a supportive context for scaling up HoPE-LVB interventions because few other initiatives have demonstrated how these policy goals can be operationalized. The success of this demonstration project is viewed as especially important in light of the post-2015 development agenda, which is also taking an integrated view of population, health, the environment and economic development.

Develop plans for how to promote learning and disseminate information

The project is carefully monitoring activities, process, outputs and results so that claims of the effectiveness of applying integrated PHE approaches can be backed up by hard data, briefs, reports, and documentaries. In addition, the team is tracking what is being learned about working towards sustainability and scaling up. In order for others to successfully replicate project interventions in the future, it is essential to document the process of implementation, for example, how the project is building the capacity of future implementers — vital information that is often lost. Such documentation is a new type of activity and maintaining it is proving challenging. At the same time, there is recognition that the extensive monitoring effort during the pilot stage will be reduced during expansion, although monitoring of key indicators and processes will continue to be required.

Efforts to disseminate progress in many forums and at multiple levels of the health and environment systems have sensitized stakeholders to PHE project approaches and encouraged substantial buy-in, e.g. interest from an existing bi-lateral USAID project in Kenya and the Kenya PHE network to support expansion of HoPE-LVB-tested innovations in the future.

Be cautious about scale up before the evidence is available

Stakeholders need to be cautioned about calling for expansion before evidence about the effectiveness of interventions has been established and before a pool of technical partners with the necessary expertise and financial support is available. For HoPE-LVB, pressure is mounting from sub-county, district and national government officials to initiate the scaling-up process before the data have been analysed. Both local communities and governments want to act in support of their populations. Pressure for early scale up has also been generated because the project is seeking to design a scalable model.

Developing a scaling-up strategy using a systematic approach

Now that the HoPE-LVB pilot is in its final stages, a review is underway to analyse project monitoring data, repeat the participatory rural appraisal done at baseline and undertake key informant interviews with a wide variety of stakeholders. The team hopes to gain insight about what is and is not working well so as to plan what a minimum package of HoPE interventions would include and how their implementation can be further simplified. This will lead to an exercise applying the ExpandNet/WHO tool for developing a scaling-up strategy in a participatory exercise with key stakeholders, so that they can collectively review the evidence and plan how to scale up the HoPE-LVB interventions if warranted.

The scaling-up strategy development process will involve careful reflection by the project team, in consultation with project steering committees and others, about:

| • | the credibility of the evidence; | ||||

| • | how interventions might be simplified; | ||||

| • | how the capacity of the implementing organizations can be strengthened; | ||||

| • | how constraints in the larger socio-political, institutional and resource environment can be addressed; and | ||||

| • | who should participate in an expanded team to support scaling-up efforts. | ||||

Strategic choices will then need to be made regarding the pace and scope of scaling up and how to disseminate the interventions to new areas, further institutionalize interventions, mobilize the necessary financial resources, and monitor the process and outcomes.

Conclusion

Consensus is growing around the need for guided approaches to scaling up of global health and development interventions, including PHE approaches, within the post-2015 development agenda. Working within a paradigm that focuses on scaling up from the time pilot projects are designed is not only new for the PHE community, but for most technical areas of global health and development. Taking a systematic approach to designing and implementing a project in ways that look ahead to sustainability and future scaling up is itself an innovation. For the HoPE-LVB Project, this has meant being thoughtful about the way interventions are implemented and who is engaged in those processes. Collaborating with governments as partners, and cultivating ownership even during the pilot, differs from many typical NGO projects. Doing so has both enhanced the local relevance of tested innovations and also the likelihood of their sustainability and scalability.

The HoPE-LVB Project team has forged new ground and will continue to do so. The entire team, including ExpandNet, is learning how complex it is to focus early project attention on the determinants of scaling-up success, especially in the multi-faceted area of PHE. Some areas of needed attention cannot be anticipated at the time of proposal-writing when interventions are not fully developed or when evidence about their feasibility and relevance for the particular setting is unknown. This has certainly been true for HoPE which has taken a different shape because of the strategic steps it has taken.

Success with scale up requires managerial and systems thinking which is typically not an area of expertise and perspective that most professionals in the health, population or environmental fields have. The ExpandNet/WHO guidance tools can assist those designing and implementing projects to employ these perspectives. It must be kept in mind, however, that beginning with scaling up in mind and then developing a scaling-up strategy prepares the ground, but it does not assure success. Efforts will be needed to ensure that the plans and commitments to scale up are eventually implemented. The HoPE-LVB team is small, but a window of opportunity has been created to successfully implement tested HoPE interventions and the PHE approach more widely within the Lake Victoria Basin region.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge support from USAID in 2011–2014, via the BALANCED Project and Evidence to Action Project cooperative agreements. In addition, we wish to thank the John D and Catherine T MacArthur Foundation and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, who have supported implementation of the Health of People and Environment in the Lake Victoria Basin Project in Uganda and Kenya. Finally, our thanks to the entire project team for their dedication and the national and international participants and stakeholders who have given their time and support to the initiative.

Notes

* For a notable exception, see De Souza.Citation3

* This review includes a qualitative and quantitative evaluation of HoPE-LVB, in which the baseline participatory rural appraisal will be repeated in concert with efforts to analyze process and monitoring data.

† The term “pilot project” is used here as a shorthand for pilot or other field tests, including demonstration projects, implementation or operations research, tests of policy changes, and proof-of-concept studies.

* The term “innovation” refers to the “service components, other practices or products that are new or perceived as new. Typically the innovation consists of a package of interventions that not only includes a new technology, practice, educational component or community initiative, but also the managerial processes necessary for successful implementation”.Citation7

* Wikipedia defines agroforestry as “an integrated approach of using the interactive benefits from combining trees and shrubs with crops and/or livestock. It combines agricultural and forestry technologies to create more diverse, productive, profitable, healthy, and sustainable land-use systems.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agroforestry.

References

- Parkin S. Closing remarks. Population Footprints Conference. UCL & Leverhulme Trust Population Footprints Symposium Report, 25–26 May 2011. London: the Leverhulme Trust; 2011, p. 12.

- RM De Souza. The integration imperative: how to improve development programs by linking population, health, and environment. Focus on Population Environment and Security. 2009; Woodrow Wilson Center: Washington, DC.

- RM De Souza. Scaling up Integrated Population, Health and Environment Approaches in the Philippines: A review of early experiences. 2008; World Wildlife Fund, Population Reference Bureau: Washington DC.

- ExpandNet World Health Organization. Beginning with the end in mind: planning pilot projects and other programmatic research for successful scaling up. 2012; WHO: Geneva.

- R Simmons, P Fajans, L Ghiron. Scaling up health service delivery: from pilot innovations to policies and programmes. 2007; World Health Organization: Geneva.

- ExpandNet World Health Organization. Practical guidance for scaling up health service innovations. 2009; WHO: Geneva.

- ExpandNet World Health Organization. Nine steps for developing a scaling-up strategy. 2010; WHO: Geneva.

- R Jowell. Trying it out – the role of pilots in policy-making: Report of a review of government pilots. 2003; National Centre for Social Research: Edinburgh.

- M McArdle. Why pilot projects fail. The Atlantic. 21 December 2011. http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2011/12/why-pilot-projects-fail/250364/

- K Hardee, L Ashford, E Rottach. The policy dimensions of scaling up health initiatives. Health Policy Project. 2012; Futures Group, Health Policy Project: Washington, DC.

- G Yamey. What are the barriers to scaling up health interventions in low and middle income countries? A qualitative study of academic leaders in implementation science. Globalization and Health. 2012; 8–11.

- T Madon, KJ Hofman, L Kupfer. Public health: implementation science. Science. 318(5857): 2007; 1728–1729.

- M McArdle. The value of health care experiments. The Atlantic. 24 January 2011. http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2011/01/the-value-of-health-care-experiments/70106/