In the lead-up to the post-2015 sustainable development agenda, thousands of people have travelled tens of thousands of miles, circling the globe many times, contributing to climate change, to attend consultations, official meetings and sessions and stay up all night in negotiations on content and language, arguing sometimes successfully and with great excitement, and sometimes bitterly and in anger, about what the new sustainable development agenda should include. The process could, on one level, be described as inclusiveness gone mad, but at the same time deserves high praise for inclusiveness compared to the process of deciding upon the Millennium Development Goals. It is, however, also deeply flawed in several ways:

by the inability to flatten the huge power differentials between participants,

by the necessity to compete to the death for even a corner of space for many issues acknowledged to be crucial, and

because the real locus of power and control is sometimes wielded by those who are not at the table when agreements are made, or who are in a small minority but have the power to sabotage agreements, whether at the last minute or in later sessions.

Global governance is a very fraught business, with very few years of history behind it as history goes. The book Governing the World: The History of an Idea, Footnote1 makes it crystal clear that those with power see the world stage as a place to seek and maintain control but also as an irritant that constantly makes demands on them to participate when they would rather not. They may participate in order not to be left out, while wanting to give away as little as possible of their autonomy and control. This book describes the frustrations and contradictions for those working in global institutions, many of whom are there for idealistic reasons, and makes it easier to understand why what they confront on a daily basis often makes them go home feeling like tearing their hair out. The “world we want” at the global level, as at the national level, is very far from the world we have.

In the case of the sustainable development goals, the future of the planet is at stake. The global community in the 21st century faces the choice of whether to allow great swathes of what is living on the Earth to die or to agree across borders to do what is necessary to ensure the future health and life of the planet for the coming generations. That is the crux of the post-2015 debate, and needs to be happening at country level at least as much as at global level.

Papers in this journal issue

About half the papers in this journal issue address a wide range of sustainable development issues, all of which bring in how they relate to the need for sexual and reproductive health and rights, with the following subjects, each representing a paper:

the role of poverty, food security and neoliberal globalisation in preventing universal access to health care;

approaches to advocacy for sustainable national funding for development;

linkages between sustainable development, demography and SRHR, and policy implications;

the evolving post-2015 agenda as seen by key players from multilateral and other agencies;

population, SRHR and sustainable development;

an analysis of the youth population boom in the global South as a catalyst for social change rather than a demographic dividend or bomb;

an ethnographic study of fertility decline and women’s views on contraceptive use in an area of Ethiopia;

the one-child policy, contraceptive use and determinants of abortion rates in China;

the one-child policy, loss of an only child and consequences for elderly care in China;

the role of resilience in response to environmental shocks and stresses and the role of integrated programmes in fostering adaptability;

a model for integrated population, health and environment programmes in a coastal area of Madagascar;

planning for sustainable scale up of an environmental conservation programme in Kenya and Uganda;

a UN Development Programme publication on gender equality, economic development and environmental sustainability;

a multi-authored book with papers on reproduction, globalisation, and the state; and

a Round Up section of summaries from the literature that focus on all the crucial issues above and add to the knowledge base that is covered in the papers.

Then there are papers that cover the subject of policy and programmes for contraception and abortion. These include:

a statement on the right to safe abortion and the post-2015 agenda, by the International Campaign for Women’s Right to Safe Abortion;

the role of conscientious objection to legal abortion following rape in a moral environment of illegal abortion in Brazil;

women’s perceptions of unsafe abortion in an area of Kenya;

South Africa’s new national contraception and fertility planning policy and service delivery guidelines, which deserve to be used as a model for their integrated and rights-based nature; and

a video competition for promoting female condoms, with links to the winning short films, which have gone around the globe on video.

Last but not least are the non-theme papers on a range of sexual and reproductive rights issues:

a statement pertaining to anti-homosexuality legislation in Africa from the Office of the Vice-Chancellor and Principal of the University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa;

a community statement from NAM/European AIDS Treatment Group that supports and provides evidence on the effectiveness of HIV treatment as prevention;

whether less severe methods of female genital cutting are slowly replacing the most severe forms in one part of Somaliland; and

the use of social media among adolescents in two cities in Tanzania and how adolescents obtain sexual and reproductive health information.

Sustainable development from an SRHR point of view

I hope this journal issue will serve as an indicator of how far things have come in the world as regards sustainable development – including from a sexual and reproductive health and rights perspective. RHM, at least, has certainly come a long way in reporting on it.

I found it salutary to re-read the first ever issue of RHM 1(1), May 1993, before editing this journal issue. “Nothing has changed” was my first reaction, but in fact, everything has changed since 1993. Awareness of the depth and breadth of population dynamics and sustainability issues, the growing threat to the Earth and its resources of destructive policies and practices, and the extent of the evidence and data available to inform conservationist and protective policies and programmes on these matters, have all increased enormously.

The outcomes we should be working for encompass every aspect of the issues covered in this journal issue, and those in turn must be seen in the even wider context of the right to health, social justice and an end to poverty and violence – which were the real point of the Millennium Development Goals, not just its measurable targets.

The papers here reflect some of the progressive thinking on these issues, and how they need to be taken forward. Some of them may take people out of their comfort zone or more hopefully will offer new areas to think about. We could easily publish more papers on these matters, and I hope we will. For example, we could look more deeply at the role of hegemonic global and national economic policies and SRHR; we could examine the crises for health, health research and health systems caused by corporate incursions and take-overs, whether by pharmaceutical companies or private, profit-making health insurers and corporations; and perhaps most importantly, we could critique the way global corporations are seeking to control the global health and sustainable development agenda while placing themselves beyond accountability to anyone for their policies and actions.Footnote2

A completely different form of man-made environmental destruction, which affects people’s lives, infrastructure, livelihoods and resources, has been revealed in photographs of the destruction of the city of Homs in Syria in these past few weeks. The military machine everywhere sucks up public money and resources, manufactures weapons of death, instils violence in young men who are then violent towards each other and women and children, and destroys cities and countryside wherever they strike. I was moved to read this week that the European Court of Human Rights has found Turkey guilty of the illegal occupation of part of Cyprus and ordered them to pay damages of €90 million.Footnote3 Can future generations hope to see a world where war is illegal and countries are held accountable for the deaths and damage they cause?

But I also despair. How can we even think about the feasibility of sustainable development in the face of an Oxfam study, released in January 2014 for the World Economic Forum in Davos, which found that there were 85 people on the planet whose financial wealth was equal to the wealth of the 3.5 billion poorest people on the planet? And that the richest individuals and companies are hiding an estimated US$ 18.5 trillion away in tax havens around the world.Footnote4 How to overcome global poverty in the face of such greed and hoarding? The picture is not a pretty one. The extent of the world’s wealth, and the barriers to re-distributing it in any socially just or equitable manner, take the breath away.

The corporate manufacturing, industrial and agricultural sectors are the main source of climate change, deforestation, polluted air/water/land, environmental degradation, resource depletion, malnutrition, forced migration, massive youth unemployment, gross income inequality, poverty and ill-health. Too many corporations are doing everything in their power to ignore or create barriers to sustainable development because it threatens their profits and their control over the Earth’s limited and disappearing resources. A combination of greed and short-termism exemplified. Others, who make an effort to implement conservationist and green policies often find themselves blocked, and their subsidies cut or withdrawn.

The global economy is sometimes seen as an immoveable force when climate change and many other sustainable development policies are discussed. Yet until the leaders of governments and national and global industries are willing to confront the reality of climate change and carbon emissions, conserve natural resources, and pursue alternatives to producing endless amounts of junk and waste, using approaches that prioritise low ecological cost and high ecological value, they will exacerbate the problems.

The papers on sustainable development and population issues in this journal issue recommend broader coalitions and innovative joint projects, e.g. by SRHR advocates and service providers with people working for green economies, environmental conservation, clean water and food security, among other things. The authors argue that all us “good guys” need to understand each others’ issues better and work together more. I hope this journal issue contributes to that happening and to improving that understanding.

Those of us who have spent our lives struggling just for sexual and reproductive health and rights, especially the keystone issues of sexual rights and abortion rights, consider those alone to be difficult enough. The statement in these pages pertaining to anti-homosexuality legislation in Africa from the Office of the Vice-Chancellor and Principal of WITS in South Africa is a reminder that hate, no matter how misplaced, can stop people from recognising the humanity of others. As regards abortion rights, we fought the demons of anti-abortion extremism and coercive population control policies leading up to and during the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) in 1994, and for a brief moment hoped we had won the battle for women’s agency and autonomy as regards controlling fertility. But the ill-conceived compromise on abortion haunts us to this day, and after we left Cairo to fight for these rights at home as well, the extent of the struggle to come quickly became clear. Many of us paid only passing attention to the Earth Summit in Rio of 1992. Little did most people realise at that time, as compared to now, how enormous environmental threats would prove to be; many more became engaged in Rio+20 in 2012 but discovered an even more complex set of issues to engage with.

Today, we are forced by reality to consider that the effects of climate change and consequent environmental disasters and stresses may mean that population growth may not even continue throughout this century, but instead, that population may decline due to major loss of life in environmental disasters.Footnote5 Thus, we may need to start thinking very differently about “population” as the 21st century progresses and how all our countries need to prepare to cope with disasters, in addition to dealing with the seven-billion-and-rising population of today. Most of the world’s major cities and economic centres are near the sea, for example. What happens if the sea, getting warmer by the year, starts rising enough to flood all those cities? For another example, take the opening paragraph of a DFID report on developing disaster resilience, which says:

“In 2010 natural disasters affected more than 200 million people, killed nearly 270,000 and caused $110 billion in damages. In 2011, we faced the first famine of the 21st century in parts of the Horn of Africa and multiple earthquakes, tsunamis and other natural disasters across the world. The World Bank predicts that the frequency and intensity of disasters will continue to increase over the coming decades.” Footnote6

This is the context in which I invite you to read this journal issue.

Circling back to where reproductive health started: family planning

I want to circle back and talk about “family planning” here, to add some perspectives in addition to what the papers in this journal issue provide. “Family planning” was out of the news for a long time after Cairo, for a whole generation in fact, but contrary to what you may have been told, people’s need to control their own fertility – and their considerable efforts to do so – never went away. Women and men need contraception and condoms now as much as they have ever done, and young people who are beginning to explore their sexuality need contraception and condoms more than anyone else – and are demanding them too. In 2008, 700–800 million women or couples (no figures available for men alone)Footnote7 around the world were using some form of contraception (why do people always talk about the ones who aren’t?) and some 43.8 million women had an abortion.Footnote8

Fertility control was not invented by FP2012; it has a history going back as far as history itself, as the pictures of IUDs past and present in show. There has been a lot of water under the bridge since “family planning” was promoted as the cure-all for the world's ills in the 1960s. And, just as then, claims are again being made that it will save the world (and the environment too). Unfortunately, it didn’t then and it won’t now, and everyone needs to study/remember that history so that the same mistakes and the same narrow vision, affecting policy and programmes, are not repeated.

My generation of activists, researchers, service providers and policymakers, who brought their knowledge together at ICPD in 1994, got the world to recognise that the need for the means to control fertility was part of a much broader set of needs related to reproduction and sexuality, and that these were inextricably interconnected. This included:

being able to have sex without fear of negative outcomes,

being able to have sex if and only if you want to, and with whom you want to,

being able to get pregnant and have the children you want,

being able to survive pregnancy in good health,

being able to have a safe abortion to end an unwanted pregnancy without fear or condemnation,

being protected from sexually transmitted infections, and

being able to get treatment for all the causes of reproductive and sexual ill-health, which start at puberty and continue into old age.

“Met need” as discussed by Sundari Ravindran and US Mishra, is the extent to which individuals are able to achieve their sexual and reproductive intentions in good health.Footnote9 There is indeed a huge unmet need in this sense, of which the unmet need for contraception is only a fraction, albeit an important one. Moreover, unmet need for contraception is about far more than lack of supplies. It is about creating a culture in which fertility control by women and their partners is accepted and promoted; it is about the whole system of delivery of contraception, abortion and sterilisation services, the quality of services, and the training of service providers. It is about service providers respecting women’s and couples’ needs, including for abortion, and helping them to find a contraceptive method that suits them, teaching them to use it consistently and correctly, and helping them to replace it with another if they encounter side effects or problems. Thus, it is not only about supply and demand, but also about the need to maintain services for and contact with people over their reproductive years in the wider context of their sexual and reproductive health.

Fertility and population policy: where RHM began

Sundari Ravindran and I started the RHM journal in 1992 because of what happened in a conference workshop in 1990, whose theme was: “Can there be a feminist population policy?” We were pilloried when we said that the answer to the question was yes, and two years later we began to work on the first issue of RHM, which we hoped would bring a women-centred perspective to these matters. Put simply, we posited that a feminist population policy was possible as long as women had the right to decide both when and whether to have children, and have autonomy over their sexual and reproductive lives. Demographic and population policy issues obviously go far beyond that proviso because they are about far more than individuals, but at that time, we were concerned about women’s right to decide as the basis of it all. We firmly believed, based on the evidence from the more developed countries, which still holds true today, that both women and men choose to have fewer children when women have alternatives apart from childrearing for how to spend their lives — that women want to be educated, have access to paid work on an equal basis with men, and the right to decide whether to have relationships and with whom.

Thinking about population dynamics and issues today, I hope that no one would argue that the global population growth of the last half century can or should be seen as unproblematic, nor the lack of balance in so many countries between young and old people either. However, I also hope that no one any longer seriously believes that distributing contraceptives will ever take care of the environmental and development problems the Earth faces, nor reduce the causes of poverty alone either.

In the poorest countries, that is, the only countries left with continuing high fertility (and high reproductive and sexual morbidity and mortality too), many people are unable to achieve their reproductive intentions. This includes not only non-users of contraception but also ever-users and current users, and everyone with an unmet need for other reproductive and sexual health services. Women living in conditions of poverty often experience a series of wanted, mistimed and unwanted pregnancies, miscarriages, stillbirths, unsafe abortions and neonatal and infant deaths,Footnote9 not only too many pregnancies. Some have fewer children than they want, due to infertility or poor and unwelcoming social conditions.

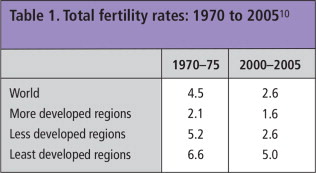

So – fertility control, birth control, yes! Maybe we should never have stopped using these terms as they unite the idea of being able to have babies, use contraception and get an abortion if needed under one roof, where all these services should be provided together, because so many men and women need them all. And, yes, things have improved hugely in most of the world since the 1960s. There has been a rapid fall in the total fertility rate globally (Table 1) thanks to economic development, increased education, women’s increased rights and freedoms, many new and effective treatments for disease, improved health and health services, and above all the development of safe methods of contraception, abortion and sterilisation. Together, these have led to a dramatic increase in the ability of more people to control their fertility, with all its attendant benefits. Do we really need to prove that today, as opposed to giving people the information and services they need, so they can take these matters into their own hands?

Table 1 Total fertility rates: 1970 to 2005Footnote10 .

Prof. Hans Rosling of the Karolinska Institute, Sweden, was on the BBC not long ago showing people that the population growth rate has been falling globally for the past 50–60 years, and that the total fertility rate dropped from 4.5 to 2.6 between 1970 and 2005 alone. Today:

42% of the world’s population already have below replacement fertility.

40% still have above replacement level but not high.

Only 18% still have high fertility, and they are almost all in the poorest, least developed countries.Footnote11

Today, the total global fertility rate is approaching 2, and some countries have well below replacement level fertility (2.1).Footnote12 Thus, the world has been very successful in having fewer children for a long time. But large population groups have been left out, and the most important ones are, in my opinion, adolescents and young people. And as long as it is called “family planning”, and as long as the assumption is that you only need it if you are married, and worse, you only have a right to be given it after you are married – a policy that remains rife in much of the global South – things are unlikely to change for the better. A transformation in thinking is urgently required.

Re-conceptualising “family planning” and changing the language

I believe it is time to reconsider what language is used to understand how people see having children vs. controlling their fertility in today’s world. Having fewer children and being able to decide whether and when to have them has opened up new worlds for women, in terms of being able to participate more fully as citizens in their countries’ affairs and to seek education and employment on an equal par with men. It has changed men’s lives too. This is a revolution and it has taken place within only a few generations. Today, awareness of the means to prevent pregnancy — and terminate unwanted pregnancy — is growing, not just because the youth population is growing, which it is, but also because more and more people now believe it is their right to decide whether and when to have children. They want fewer children (or none at all) and more and more, they feel entitled to the means and information to do so. This represents a sea change from “accepting all the children God gives”.

At the same time, due to improved health, people are living longer, the average age at menarche has been falling, and menopause is happening later. In the UK, the average age at menarche is currently 13, meaning half the girls experiencing it are younger, while the average age at menopause is 52. Thus, women today may have as many as 40 fertile years, or ±520 menstrual cycles. With an average of only two children, they may need protection against pregnancy for almost all of those years. That’s a lot of protection!

Moreover, women are having their babies later. Of all women born in England & Wales in 1950, 42% were childless at age 25, and 15% at age 40. Of women born in 1965, 60% were still childless at 25. The average age of a woman having her first child in 2004 was 27 and in 2006 it had risen to 30.Footnote13, Footnote14, Footnote15 Thus, in developed countries, at least, there may be ten or more years between first sex and first baby.

In contrast, in many African and Asian countries, young women are having first and probably second babies very young and very soon after first sex, because they aren’t using protection, and then they tend to want to stop getting pregnant early too. Worldwide, babies or no babies, young people (aged 15–24) experience by far the most unwanted pregnancies, STIs and HIV. Why? Because they are in their most fertile years, they are having the most sex, and are the most likely to be engaged in unequal power relationships, in which it is difficult to negotiate sex, let alone safer sex and contraception. Yet they have the least access to information and and providing adolescents with contraception and safe abortion services is still taboo.

“Family planning” is a crucial concept at the time in people’s lives when they are thinking about or ready to have children and thinking about or trying to get pregnant. But for most adolescents and young people, for those who don’t want children, and those who have already had the children they want, sex without fear of pregnancy is what they seek. “Family planning” is not relevant as a concept at every point in their sex lives. They need sexual health services that include contraception, abortion and sterilisation information and provision. I keep stressing this because the 20th century concept of family planning too often excluded (and in many countries still does exclude) young, single people. And those who provided contraception, abortion and sterilisation back then were often hidden away in different bits of health services, with many located in hospitals and/or the same place as maternity care. Yet things have changed enormously since these services were first initiated. I haven’t done the homework on this, but I would venture a guess that the configuration and placement of these services in many countries is not optimal, not high quality, and possibly very outdated. In many places the number of contraceptive methods offered is severely limited, made worse by stockouts, and abortion methods still being used (especially D&C) are no longer recommended by WHO. Certainly if the papers RHM has published about how young people are treated by these services over the years hold true, the situation needs serious attention.

And what about methods? So much has changed in this area too. With many more safe and effective methods for avoiding and terminating pregnancy available today, it seems there is far less tolerance of failure to use a method — or a decision to choose a less effective method — among those providing contraceptives and those making policy on providing them. This arises, in my opinion, because abortion is still looked down on, discouraged and stigmatised, something women continue to be condemned for needing. Yet between one in three and one in five women in every country of the world, even in the crowds that ecstatically greet the Pope on his travels, will have an abortion in her lifetime. It is misogyny to deny safe abortions to women, nothing less.

And how many providers still look down on condoms, even in high STI/HIV settings? It’s brilliant that South Africa’s new policy on fertility and contraception, summarised in this journal, integrates attention to methods of fertility control but also HIV prevention, condoms, sex education and safer sex. In 1979, Christopher Tietze, a staunch early supporter of abortion for public health reasons in the USA, showed that condoms + early abortion together were the safest and most effective form of birth control from a sexual health/STI prevention/preventing unwanted pregnancy perspective. In spite of the availability of manual vacuum aspiration and medical abortion today, which can be used very early on in a pregnancy if a condom fails, this truth has been all but forgotten, and has virtually disappeared from the literature along with the concept of safer sex. Let’s bring it back!

It’s been decades since “contraceptive acceptability” studies were carried out asking women and men about their method preferences, such as those in a supplement RHM published for WHO in 1997.Footnote16 I keep waiting for quality of family planning services to come back on the agenda, such as was addressed in a comprehensive 1994 manual on indicators for evaluating family planning programmes.Footnote17 Perhaps it’s time to set up current studies in this area, before options begin to be closed down. Given continuing provider biases and people’s often different needs and concerns, it is important to find out whether all contraceptive users actually do want to use longer-acting reversible methods (LARCs – especially implants and IUDs) to the exclusion of any others. LARCs are in vogue because they are not user-dependent and reduce user failure to a large degree. At the same time, so-called “repeat abortions” (and other abortions too) are being demonised. There is a connection there, potentially an insidious one. But do teenagers having intermittent sex really belong on a long-acting reversible method, and is that what they actually want? If yes, fine! If not, back off!

If LARCs are the only methods being pushed by today’s leaders in family planning, then why are female sterilisation rates going down, when the procedure has become so simple and safe? And why have vasectomy rates never really gone up when more men than ever are supportive of fertility control? The numbers of people with 10–25 years of fertility left after they finish childbearing is rising rapidly. Why are LARCs considered preferable to male or female sterilisation? Is someone trying to ensure pharmaceutical companies make big bucks from this, rather than supporting health systems to carry out these minor surgeries?

Having as many methods as possible to choose from used to be seen as a good thing, because it led to both greater choice and higher uptake. This was considered a truism. If method failure is treated as a moral failure, rather than a part of life, then a lot of perfectly acceptable methods will fall by the wayside. Is it really progress to stigmatise contraceptive failure as well as abortion? There are many reasons why people would prefer their contraceptive method not to interfere in their sex lives, and not to have to worry about it failing, but does that mean everyone? Do we really need to go back to the bad old days of “Only we know what’s best for you”? These subjects need to be discussed in depth again in our field, now that promotion of contraception is back on the agenda.

Still not a panacea for poverty – or sustainable development

However, just as “family planning” is not a panacea for poverty it is also not a panacea for dealing with over-consumption, obesity, malnutrition, food insecurity, resource depletion or environmental shocks and stresses. And it won’t get governments realising that they need to develop green economies and renewable energy sources right now, either. I hope I’m no longer the only person in the world who thinks windfarms are beautiful and solar panels essential, because most of us live in places that have either a plethora of wind or a plethora of sun!

Windpark, Aragon, Zaragoza, Spain, pioneering the modern use of windpower, which produces 10% of the electricity used in Spain from wind, 2008

I’m all for making common cause with activists on climate change and other development and environmental activists, as I said before. But I would also like to see the advocates for FP2020, rights-based population policy, development, maternal and child health, HIV and STIs, infertility, abortion rights and sexual rights making common cause together too. I’m sick of hearing all praise for the ICPD Programme of Action from people calling themselves advocates of sexual and reproductive health who at the same time refuse to condemn its restrictions on the right to safe abortion. I’m pleased we can publish the statement on safe abortion and the post-2015 agenda by the International Campaign for Women’s Right to Safe Abortion in this journal issue, and I will be helping to send it round to those same leaders. There’s no space for condemning one aspect of reproductive rights and claiming to support another; it isn’t good enough.

Rich people should not be allowed to use their money, nor the Pope his position, nor others like them, especially in the name of religion, to buy silence on issues that they may find personally uncomfortable or even offensive, which by any definition are central to any sustainable development agenda one might devise. That other leaders, who know better, allow them to get away with it is criminal, plain and simple. Unchallenged, such forces will taint the sustainability development goals just as they did the MDGs and the ICPD Programme of Action, and cripple the possibility of ensuring that the new goals respect, protect and fulfil human rights and promote gender equality, which depends on sexual and reproductive rights.

From these understandings, the whole basis for why and how sexual and reproductive health needs are essential for fulfilling a progressive population and sustainable development agenda emerges. Key players in the field warn in a paper here that none of this will come easy as the post-2015 scenario proceeds and is taken over by governments. I’m not a praying sort of person, but I pray we don’t lose that vision in the back rooms of the UN ever again.

The real complexity of defining the sustainable development agenda should not get sidetracked by anti-rights clamour. It should keep a steady course of trying to sort out how to transform global and national governance, finance, law and policy that promotes and protects the right to health, with special provisos for women, adolescents and young people, and recommend economic policies intended for the welfare of the many, not the benefit of the few, and regulate corporate manufacturing, industry and farming – so as to be able to maintain and renew the Earth and its resources, support its people, and preserve and protect the future.

Acknowledgement

TK Sundari Ravindran is RHM’s co-founder and first and only co-editor (at least so far!). She has been an inspiration to me for as long as I have been editing this journal. Given that this issue is about the same subjects we started off with together, I want to acknowledge her here for teaching me much of what I understand about social justice and political economy today.

Notes

1 London: Penguin, 2012. http://www.penguin.co.uk/nf/Book/BookDisplay/0,,9780713996838,00.html

2 The EU and Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, currently being “negotiated”, would make governments beholden to corporations, force competitive tendering for all services, including publicly owned and provided services such as health care, and even allow corporations to sue governments for loss of income, e.g. as a result of protective public health policies. See http://mondediplo.com/2013/12/02tafta, 2 December 2013. p. 1.

3 European court orders Turkey to pay damages for Cyprus invasion. The Guardian. 14 May 2014. http://www.theguardian.com/law/2014/may/12/european-court-human-rights-turkey-compensation-cyprus-invasion

5 Presentations by Hania Zlotnik, former Head of the UN Population Division, and by others at the Population Footprints conference, London 2011. http://www.ucl.ac.uk/silva/popfootprints/publications/popfoot_report

6 Defining disaster resilience: a DFID approach paper [Internet]. London: Department for International Development; November 2011. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/186874/defining-disaster-resilience-approach-paper.pdf

7 In my opinion, data collection on sexual and reprodutive health matters covering married women only should be banned, and leaving men out should be banned too.

8 Shah I, Åhman E. Unsafe abortion differentials in 2008 by age and developing country region: high burden among young women. Reproductive Health Matters 2012;20(39):169–73.

9 Ravindran TKS, Mishra US. Unmet need for reproductive health in India. Reproductive Health Matters 2001;9(18):105–13.

11 Prof. Hans Rosling. www.gapminder.org

12 I find it actually very concerning that no one submitted a paper for this journal issue that addressed below replacement fertility and the policy aberrations it is causing among pronatalist-leaning governments, such as Russia and countries of Eastern Europe. This is a serious problem for women, because the first thing demanded of them is to have more babies and the first thing to be taken away, to try and force them to do so, is contraception and legal abortion. The causes and consequences of below replacement fertility needs more study.

13 Johnson G. Based on figures from the Office of Population Censuses and Surveys. Quoted in: Bailey R. Women who don’t want children. www.rosemarybailey.com/?page_id=248

14 OECD family database – mean age of mothers at first childbirth. http://www.oecd.org/els/soc/SF2.3%20Mean%20age%20of%20mother%20at%20first%20childbirth%20-%20updated%20240212.pdf

15 Average age of woman having first child continues to rise due to 'spending more time in education’. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-2201023/Average-age-woman-having-child-continues-rise-spending-time-education.html#ixzz2TwpW5MgZ

16 Beyond Acceptability: Users’ Perspectives on Contraception. London: RHM for WHO; 1997. http://www.rhmjournal.org.uk/publications/beyond-acceptability/BeyondAcceptability.pdf

17 For one of the best manuals on indicators for evaluating and ensuring quality of care in contraceptive services, see: Bertrand JT, Magnani RJ, Rutenberg N. Handbook of Indicators for Family Planning Program Evaluation. The Evaluation Project, University of North Carolina. December 1994. At: www.cpc.unc.edu/measure/publications/pdf/ms-94-01.pdf