Abstract

Medical abortion was introduced in Nepal in 2009, but rural women’s access to medical abortion services remained limited. We conducted a district-level operations research study to assess the effectiveness of training 13 auxiliary nurse-midwives as medical abortion providers, and 120 female community health volunteers as communicators and referral agents for expanding access to medical abortion for rural women. Interviews with service providers and women who received medical abortion were undertaken and service statistics were analysed. Compared to a neighbouring district with no intervention, there was a significant increase in the intervention area in community health volunteers’ knowledge of the legal conditions for abortion, the advantages and disadvantages of medical abortion, safe places for an abortion, medical abortion drugs, correct gestational age for home use of medical abortion, and carrying out a urine pregnancy test. In a one-year period in 2011–12, the community health volunteers did pregnancy tests for 584 women and referred 114 women to the auxiliary nurse-midwives for abortion; 307 women in the intervention area received medical abortion services from auxiliary nurse-midwives. There were no complications that required referral to a higher-level facility except for one incomplete abortion. Almost all women who opted for medical abortion were happy with the services provided. The study demonstrated that auxiliary nurse-midwives can independently and confidently provide medical abortion safely and effectively at the sub-health post level, and community health volunteers are effective change agents in informing women about medical abortion.

Resumé

L’avortement médicamenteux a été introduit en 2009 au Népal, mais l’accès des femmes rurales aux services est demeuré limité. Nous avons étudié les opérations au niveau d’un district pour évaluer l’efficacité de la formation de 13 infirmières sages-femmes auxiliaires comme prestataires de l’avortement médicamenteux, et de 120 femmes comme bénévoles de santé communautaire et agents d’orientation pour élargir l’accès des femmes rurales à l’avortement médicamenteux. Des entretiens ont été organisés avec des prestataires de service et des femmes ayant mené un avortement médicamenteux, et des statistiques de service ont été analysées. Par comparaison avec un district voisin où aucune intervention n’avait été réalisée, dans la zone d’intervention, on a constaté une hausse sensible de la connaissance des bénévoles de santé communautaire sur les conditions juridiques de l’avortement, les avantages et les inconvénients de l’avortement médicamenteux, les lieux sûrs pour l’avortement, les médicaments abortifs, l’âge gestationnel correct pour pratiquer un avortement médicamenteux à domicile et la réalisation d’un test de grossesse urinaire. Sur une période d’un an en 2011-2012, les bénévoles de santé communautaire ont effectué un test de grossesse pour 584 femmes et adressé 114 femmes qui voulaient avorter aux infirmières sages-femmes auxiliaires ; les infirmières sages-femmes auxiliaires ont prêté des services d’avortement médicamenteux pour 307 femmes dans la zone d’intervention. Aucune complication n’a exigé l’aiguillage vers un centre plus spécialisé, à l’exception d’un avortement incomplet. Presque toutes les femmes qui avaient opté pour l’avortement médicamenteux étaient satisfaites des services obtenus. L’étude a montré que les infirmières sages-femmes auxiliaires peuvent pratiquer efficacement, indépendamment et en confiance des avortements médicamenteux en toute sécurité au niveau des sous-centres de santé, et que les bénévoles de santé communautaire sont de précieux agents de changement pour renseigner les femmes sur l’avortement médicamenteux.

Resumen

Los servicios de aborto con medicamentos fueron introducidos en Nepal en 2009, pero el acceso de las mujeres rurales a dichos servicios continu ó siendo limitado. Realizamos un estudio de investigación operativa a nivel de distrito para evaluar la eficacia de capacitar a 13 enfermeras-obstetras auxiliares como prestadoras de servicios de aborto con medicamentos, y 120 voluntarias comunitarias en salud como comunicadoras y agentes de referencia para ampliar el acceso de las mujeres rurales a dichos servicios. Se realizaron entrevistas con prestadores de servicios y mujeres que recibieron servicios de aborto con medicamentos y se analizaron las estadísticas de los servicios. Comparado con un distrito aledaño donde no hubo intervención, en la zona de la intervención se vio un considerable aumento en los conocimientos de las voluntarias comunitarias respecto a las condiciones para un aborto legal, las ventajas y desventajas del aborto con medicamentos, lugares seguros para tener un aborto, fármacos para inducir el aborto, edad gestacional correcta para el uso domiciliario de los medicamentos para inducir el aborto, y realizar una prueba de embarazo en la orina. En el plazo de un año, 2011-12, las voluntarias comunitarias en salud realizaron pruebas de embarazo en 584 mujeres y refirieron a 114 mujeres a enfermeras-obstetras auxiliares para aborto; 307 mujeres en la zona de la intervención recibieron servicios de aborto con medicamentos de enfermeras-obstetras auxiliares. No hubo complicaciones que necesitaron referencia a una unidad de salud de mayor nivel, excepto un aborto incompleto. Casi todas las mujeres que optaron por tener un aborto con medicamentos estuvieron contentas con los servicios que recibieron. El estudio demostró que las enfermeras-obstetras auxiliares pueden proporcionar servicios de aborto con medicamentos de manera independiente, confiada, segura y eficaz, en un nivel inferior al puesto de salud, y las voluntarias comunitarias en salud son agentes de cambio eficientes para informar a las mujeres acerca del aborto con medicamentos.

The abortion law was reformed in Nepal in September 2002 to improve the health status and condition of women. The law allows abortion up to 12 weeks of pregnancy at the request of the woman, up to 18 weeks if the pregnancy results from rape or incest, and at any time during pregnancy on the advice of a medical practitioner, if the physical or mental health or life of the woman is at risk, or the fetus is impaired or has a condition incompatible with life.Citation1 Previous laws did not allow abortion under any circumstances and many women who had had an abortion were imprisoned.Citation2 The introduction of legal abortion has been characterized by a committed effort by the Ministry of Health and Population and non-governmental organizations to rapidly scale up access to safe abortion. Manual vacuum aspiration services became available in 2004; second-trimester procedures were introduced in 2007; and senior nurses who had prior training in post-abortion care began providing services in 2008.Citation2 Manual vacuum aspiration was the only safe abortion method used until 2009 in Nepal. In line with the Safe Abortion Service Directives 2065 B.S. (2008), the Government of Nepal introduced medical abortion on a pilot basis in six districts through 32 accredited comprehensive abortion care centres for a period of one year in 2009, with a 96.1% success rate. The experience gained encouraged the Government to scale up medical abortion services in all accredited abortion clinics throughout the 75 districts of the country in a phased manner. However, medical abortion services are still limited to a relatively small number of accredited government and non-governmental centres, including selected primary health centres and health posts. No sub-health post was approved for medical abortion provision before this study.

Despite these efforts, knowledge and use of medical abortion has been discouragingly low. An evaluation study of medical abortion services in the six pilot districts, carried out by the Center for Research on Environment Health and Population Activities (CREPHA) in 2009, showed that only 15% of 1,093 married women of reproductive age had heard about medical abortion.Citation3 Government records from the six pilot districts revealed that of the women who had had an abortion in that period, only 6.1% had opted for medical abortion.Citation3 The study also found a number of other barriers:

| • | no full-time counsellor at the government facilities to provide information on medical abortion that would enable women to make an informed choice; | ||||

| • | negative attitudes on the part of providers towards medical abortion; | ||||

| • | a policy that barred women living more than two hours’ distance from the health facility from using medical abortion; | ||||

| • | low confidence in medical abortion efficacy among the providers; and | ||||

| • | the requirement of repeat visits to the clinic.Citation3 | ||||

The findings contributed to elimination of the policy that stipulated that women living more than two hours from a health facility could not use medical abortion, and also helped provide a choice for women of home or clinic use of misoprostol.

Although medical abortion provision in recent years in Nepal has been expanding, restrictions on certification of facilities and provider provision remain in place. Rural women’s access to medical abortion services remains limited due to the government’s reluctance to expand the services to outreach health centres, particularly at the sub-health post level (the lowest level of health facility in the government health system) through auxiliary nurse-midwives.

Previous research in Nepal had demonstrated that medical abortion provision by doctors, nurses and auxiliary nurse-midwives is acceptable and feasible.Citation4,5 More recently, a World Health Organization study by CREHPA showed that mid-level providers could provide medical abortion from certified facilities with the same safety and effectiveness as doctors.Citation6 These findings were in line with research elsewhere indicating that non-clinicians can safely provide first-trimester abortion.Citation6–8

Medical abortion has the potential to expand women’s access to safe abortion in Nepal by overcoming the need for a skilled provider in a clinic setting, as needed with aspiration abortion.Citation8–10 It also increases affordability and privacy.Citation11,12 Most importantly, it offers the opportunity to decentralize provision of services away from traditional hospital and clinic settings.Citation13

Increasing the utilization of medical abortion requires knowledge and motivation. Studies conducted elsewhere have shown that training and advocacy at different levels of the health system, use of mass communication channels, and mobilisation of community-based groups have been effective in increasing utilisation of contraception, HIV and child health services.Citation14,15 The grapevine is also very effective in spreading the word about misoprostol all over the world, in spite of laws against abortion and in the absence of formal information. However, the effectiveness of using community-based volunteers in increasing awareness about medical abortion and establishing referral systems in rural areas in countries like Nepal has not been studied.

The female community health volunteer programme in Nepal was introduced by the Ministry of Health and Population in 1988. Currently, over 50,000 women serve as an important source of information for communities in nearly all rural areas. They enjoy high respect and acceptability because they play an important role in contributing to key public health programmes, including family planning, maternity care, child health, vitamin A supplementation, deworming and immunization coverage.Citation15,16 However, they have not been trained or involved in providing information or referral for safe abortion care, including medical abortion.

This study, in two western districts of Nepal in 2011 and 2012, assessed the effectiveness of training 13 auxiliary nurse-midwives based in health posts and sub-health posts to provide medical abortion independently, and 100 female community health volunteers as communicators and referral agents for expanding medical abortion access to rural women.

Data and methods

The study employed a non-equivalent comparison group design that compared the effect of training auxiliary nurse-midwives to provide medical abortion and female community health volunteers in the intervention group (Rupendehi district) against a similar, but not necessarily equivalent, comparison group located in the neighbouring district (Kailali). Rupendehi has 69 village development committees and two urban municipalities, two hospitals, five primary health care centres, six health posts and 57 sub-health posts. Prior to the implementation of the study, only two government hospitals, three NGO-managed clinics and three private clinics located in Rupendehi were offering medical as well as aspiration abortion services. The present study selected one primary health care centre, five health posts and two sub-health posts (approved as a birthing centre with the presence of at least one auxiliary nurse-midwife) and 120 female community health volunteers from 10 village development committees in the intervention district in consultation with the district health officials and stakeholders. The selection of the intervention area was based on the criteria that no outreach health centre was providing medical abortion services and that the district health officials were supportive of the study. In the comparison area, two primary health care centres and two health posts that had been offering medical abortion services since January 2009 and 96 female community health volunteers from ten village development committees were selected in consultation with district health officials. Both areas were very similar in terms of socio-economic and demographic indicators.

The interventions were carried out at two levels. At the community level, 120 female community health volunteers (a minimum of ten female community health volunteers per village development committee) were trained to communicate information about prevention of unintended pregnancy, abortion law and rights, safe (government-approved) health centres for abortion and legal abortion services, health consequences of unsafe abortion, safety and efficacy of medical abortion, importance of post-abortion/post-partum contraception, availability of medical abortion at health and sub-health posts through trained auxiliary nurse-midwives, and women’s choice of place for misoprostol use (either self-administration at home or at the clinic). They were also trained to perform a urine pregnancy test and check eligibility criteria for women asking for medical abortion at health and sub-health posts. After training, the women were given ten sets of urine pregnancy test kits each so that they could maintain this skill and sustain this service by charging women a small amount (US$ 0.26) for a pregnancy test. They were also issued with special referral cards to give to women with a positive test result, either for antenatal care or abortion. Women receiving referral cards for abortion were later visited at home by the same female community health volunteer who had given them a referral card, to find out the outcome of the referral and for post-abortion or post-partum family planning advice.

All 13 auxiliary nurse-midwives working in the eight study health centres and who were already certified as skilled birth attendants were given comprehensive training on providing medical abortion, women’s choice on misoprostol use either self-administered at home or in the clinic, management of minor complications and identification of complications requiring immediate referral. The training was conducted by three national trainers at the government’s National Health Training Centre, following the national medical abortion training protocol, whose requirements included three days’ training at the main Maternity Hospital in Kathmandu. All trained auxiliary nurse-midwives received government approval before starting medical abortion services in their health facilities.

In addition, the district health office supplied 300 sachets of medical abortion tablets (mifepristone 200 mg x 1 and misoprostol 200mcg x 4 in the same pack) and 300 copies of the self-assessment card to be used by women to the eight outreach health centres. No intervention was implemented in the comparison area.

The core study protocol and research instruments were approved by the Nepal Health Research Council (national ethical approval body) and the World Health Organization’s Research Ethics Review Committees. Participants (female community health volunteers, women, and auxiliary nurse-midwives) involved in the study were fully informed about the nature of the study, research objectives, and confidentiality of the data. Participants’ written consent (thumbprint if not literate) was obtained regarding their participation in the study. Confidentiality of information was ensured by removing personal identification from the data and by securing access to all data and information.

We analyzed matched (paired data) pre- and post-intervention individual interviews with 110 female community health volunteers in the intervention area and similar interview data (but no intervention) with 79 female community health volunteers in the comparison area. Data at baseline and post-intervention were collected. The female community health volunteers were mainly asked about knowledge of existing abortion law, abortion-seeking behaviour of women in their communities, and their own knowledge and perceptions of medical abortion, involvement in urine pregnancy tests, referrals and providing abortion. Similarly, auxiliary nurse-midwives were asked about their training and skills on abortion, number of women whose abortions they managed, management of complications, and their knowledge and perceptions of medical abortion.

After the intervention, we also carried out semi-structured interviews with 13 auxiliary nurse-midwives (nine in the intervention area and four in the comparison area) who provided medical abortion services. Additionally, we carried out 241 exit interviews with women (124 in the intervention area and 117 in the comparison area) who had received medical abortion services from the 12 study facilities (eight in the intervention area and four in the comparison area) over a four-month period.

Interviews with women who had abortions were carried out between the sixth and tenth month of the intervention period. Along with their socio-demographic characteristics, women were asked what they knew about abortion clinics, abortion law, abortion experiences, and contraceptive counselling and use. Eight trained research assistants (four in the intervention area and four in the comparison area), stationed for four months at the study facilities, conducted the exit interviews. We also analyzed the 12 months of service statistics data maintained by the study health facilities.

As the female community health volunteers’ interview data were matched, McNemar tests were used to examine whether the difference in knowledge of, and perception about, medical abortion and referral practices between pre-and post-intervention was greater in the intervention area than in the comparison area. Exit interview data were also compared to examine the differences in women’s perceptions of medical abortion services intervention and the Chi-square test of association was also used to test whether the differences were independent.

Profile of study participants

Female community health workers

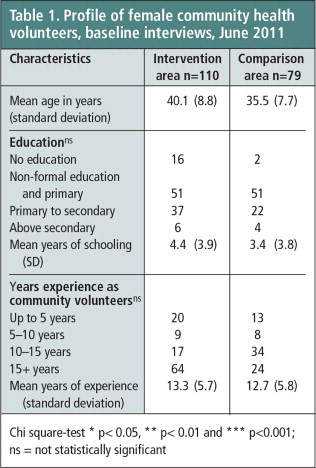

The mean age of female community health volunteers was slightly higher in the intervention area than in the comparison area (40.1 and 35.6 years, respectively) (Table 1). Their ages ranged from 18—60 years, with the great majority over age 25. A higher percentage were illiterate in the intervention area than in the comparison area. On average, they had served more than 13 years as community health volunteers (range 1—23 years).

Women who had a medical abortion during the study

The socio-demographic characteristics of the women who received medical abortion services and were interviewed (124 in the intervention area and 117 in comparison area) ranged in age from 15—53 years. A slightly higher percentage of women in the intervention than in the comparison area had never attended school (26.6% vs 21.4%). Over 70% of women in both areas had had at least two children.

Auxiliary nurse-midwives

Six out of nine auxiliary nurse-midwives who were interviewed in the intervention area were working at health posts, two at sub-health posts and one at a primary health care centre. Most of these auxiliary nurse-midwives had been working at these health centres for more than a year. In the comparison area, all four auxiliary nurse-midwives interviewed were working in the health posts for more than a year.

Findings

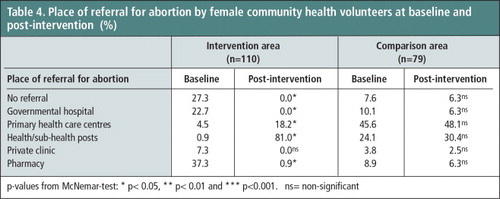

Female community health volunteers’ knowledge of medical abortion

Table 2 shows a significant increase in female community health volunteers’ knowledge about the legal conditions of abortion, government-approved health facilities for abortion, medical abortion medications and the correct gestational age for medical abortion at baseline and post-intervention in the intervention area as compared to the comparison area. For example, in the intervention area, knowledge about the legal grounds for abortion increased from 66% at baseline to 100% post-intervention, while remaining the same in the comparison area. Knowledge of the names of approved medical abortion drugs also increased from 1% at baseline to 97% post-intervention. Similarly, there was a sharp increase in knowledge about the upper time limit for home use of medical abortion (≤9 weeks) in the intervention area from 2% at baseline to 69% post-intervention.

Table 2 Increased knowledge and practice on abortion among female community health volunteers, baseline and post-intervention (%) p-values from McNemar-test: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001, ns = non-significant.

There was also a significant increase in knowledge and use of urine pregnancy test kits, particularly in the intervention area. The comparison group also showed a significant increase in knowledge of medical abortion medications, correct gestation period and performing a urine pregnancy test, although the magnitude of change was lower than in the intervention group. Increases observed in the comparison area may reflect improvements as in other parts of the country.

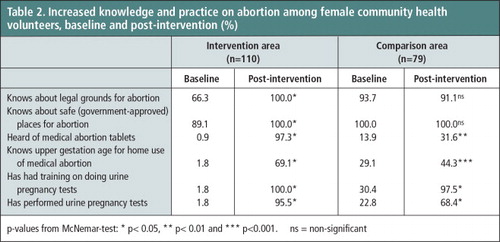

Table 3 shows the changes in female community health volunteers’ knowledge about the advantages and disadvantages of medical abortion between baseline and post-intervention. This included a significantly increased percentage at post-intervention who believed that medical abortion was safe (low risk), is an alternative to MVA, allows abortion to happen as a natural process, and ensures privacy, whether at home during the abortion process or in that nobody from her family knows about her abortion if in the clinic. Similar changes, particularly that they believe medical abortion is safe, requires no aspiration procedure and causes no physical trauma was also observed in the comparison area but the magnitude of changes was much lower than in the intervention area. For example, at baseline, about 12% of the female community health volunteers in the intervention group and 15% in the comparison group mentioned that one of the advantage of medical abortion was that it is a low risk method. At the post-intervention survey, these percentages increased by 70 percentage points in the intervention group and 39 percentage points in the comparison group. The percentage of female community health volunteers who reported lack of knowledge about the advantages of medical abortion significantly fell from 59% at baseline to 2% post-intervention in the intervention area.

Table 3 Increases in female community volunteer’s knowledge about advantages and disadvantages of medical abortion a Percentage total may exceed 100 due to multiple responses. p-values from McNemar-test: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001, ns = non-significant.

In the post-intervention phase, in both the intervention and comparison areas, more of the female community health volunteers knew that there was a risk of incomplete abortion for a small minority of women and an even smaller risk of heavy bleeding. Changes in their knowledge of disadvantages of medical abortion — including issues related to pain, side effects from the misoprostol, and longer duration of the process than with aspiration abortion — were insignificant. This means that further information needs to be provided in future training.

Contribution of female community health volunteers and changes in practice due to the study

In the 12 months of the study, 584 urine pregnancy tests were performed by the female community health volunteers in the intervention area, of which 323 were positive. Of these 323 women, 209 were referred to antenatal care services (their pregnancies were desired) and the remaining 114 women opted for an abortion (108 for medical abortion and 6 for manual vacuum aspiration). Female community health volunteers referred the women opting for an abortion to the nearest health centres and issued 108 of them with referral cards for the medical abortion service. Of the 108 women referred, 80 actually attended the referral health centres, and all of the 80 had a medical abortion. The remaining 28 women either changed their minds and continued the pregnancy or were turned away from the abortion services due to higher gestational age (more than 9 weeks)Footnote* or had medical contraindications to abortion such as signs and symptoms of heart disease, for example, high blood pressure.

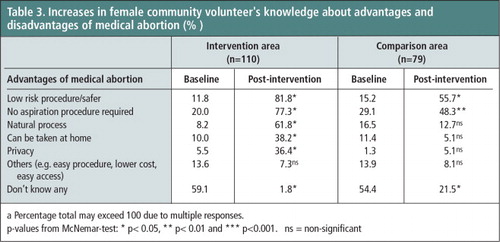

The female community health volunteers were asked where they referred women for abortion most often both at baseline and post-intervention interviews. Responses (Table 4) show that referral of women to health and sub-health posts increased significantly in the intervention area as compared to the comparison area. At baseline, almost none of the volunteers in the intervention area and 25% of those in the comparison area said they referred women opting for abortion to health and sub-health posts. Post-intervention, these percentages increased by 80 percentage points in the intervention area though only 5 percentage points in the comparison area. Similarly, referral to the primary health care centres also increased significantly in the intervention area at the post-intervention survey compared to the baseline (from 4.5% to 18.2%), whereas there was no significant change in the comparison area (from 45.6% to 48.1%). Referral to a pharmacy for abortion, which is not legal in Nepal, was reduced significantly in the intervention area (from 37.3% at baseline to 0.9% post-intervention) whereas in the comparison group the percentage (from 8.9% to 6.3%) did not change significantly.

Number of medical abortions and abortion success rate

Service statistics showed that 307 women in the intervention area and 289 women in the comparison area had received medical abortion services from auxiliary nurse-midwives in the one-year study period. Of the 307 women, there were five incomplete abortions (1.6%), four of which were treated with manual vacuum aspiration by the auxiliary nurse-midwives. Only one woman was referred to the nearest zonal hospital because it was a Saturday, and the outreach health centre was closed. Of the 289 women in the comparison area, there were seven incomplete abortions (2.4%), five of which were treated with manual vacuum aspiration and two were referred to the district hospitals. The difference in the number of incomplete abortions between the two areas was not statistically significant.

Confidence of auxiliary nurse-midwives providing medical abortion services

Interviews with the auxiliary nurse-midwives participating in this study in the intervention area revealed that all nine of them were confident about providing medical abortion independently, and they also expressed a strong desire to receive training in manual vacuum aspiration and additional skills, particularly in management of complications and clinical assessment. Auxiliary nurse-midwives working in the comparison area expressed similar views and interests.

“Initially I used to get worried about women who received medical abortion from me. I had to make frequent calls to them regarding their condition. I felt relieved only after they informed me that they were fine as the pills had worked well. Now I am more confident than before. I have provided medical abortion to a lot of women. So far none of these women has experienced incomplete abortion or a complication with medical abortion. I now realize that we are as capable of providing medical abortion as any other providers.” (ANM working at sub-health post, intervention area)

“I feel that I have provided medical abortion services to many women successfully. My confidence to provide medical abortion service has increased over this period, and I think the government should train us [auxiliary nurse-midwives] to provide manual vacuum aspiration services also.” (ANM working at health post, intervention area)

Women’s experiences of medical abortion care from an auxiliary nurse-midwife

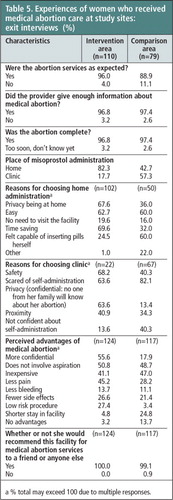

We conducted 241 exit interviews with women (124 in the intervention area and 117 in the comparison area) who received medical abortion care from an auxiliary nurse-midwife at one of the 12 outreach health facilities (eight in the intervention area and four in the comparison area). We learned that 96% of the women in the intervention area and 89% of the women in the comparison area reported that the services met their expectations (Table 5). About 97% of women in both intervention and comparison areas reported a complete abortion. The women reported only typical and well-known, short-term side effects such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, abdominal pain, chills and fever.

Table 5 Experiences of women who received medical abortion care at study sites: exit interviews a -% total may exceed 100 due to multiple responses.

In the intervention area, 82.3% of women opting for medical abortion chose self-administration of misoprostol at home, compared to 42.7% in the comparison area. The two main reasons for choosing home administration were: saving the time required to stay at the facility, followed by privacy and convenience. Those women who chose the clinic for misoprostol administration said they were scared, or felt safer and had more confidence at the clinic than at home. Almost all the women (96.8% in the intervention area and 97.4% in the comparison area) felt that they had received enough information about medical abortion from the counsellors/providers. Confidentiality, not requiring aspiration, less pain and less cost were perceived as the main advantages of medical abortion. In addition, all the women from both areas reported that they would recommend to their friends or others to attend the facility they visited for medical abortion services.

Discussion and conclusions

In this study, 307 women in the intervention area received medical abortion services from auxiliary nurse-midwives in a one-year period and had no complications that required referral to higher level facility except for one incomplete abortion. Auxiliary nurse-midwives showed that they were capable and interested in providing a good quality medical abortion service safely and effectively at outreach health facilities without the presence of physicians, and were confident of their ability to do so, with very limited clinical resources. This confidence was underpinned by the evidence, in that almost all abortions were complete, no serious adverse events were recorded, and women reported only typical and well-known, short-term side effects. Furthermore, interviews showed that the women who had had a medical abortion were happy with the service they had received and were willing to recommend this service to friends and other women.

Our study also found that female community health volunteers were capable of providing information to women and referrals to auxiliary nurse-midwives with the aim of increasing access to medical abortion services among rural women. We therefore recommend that female community health volunteers should continue to play this role both for medical abortion and for manual vacuum aspiration, urine pregnancy tests, post-abortion/delivery contraceptive counselling and follow-up.

The safety, efficacy and acceptability of medical abortion provided by auxiliary nurse-midwives is now well established in Nepal,Citation6 and this study establishes it even further. To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the possibility of introducing medical abortion services at the sub-health post level in Nepal.

There is no policy restriction on sub-health posts (if already approved as a birthing centreFootnote* ) applying for government certification for providing abortion services. However, as of June 2013, no sub-health post (except for the ones in this study, who have continued to provide medical abortion services) had been accredited for providing medical abortion services in Nepal.

On the basis of our findings, we encourage the government to consider accrediting sub-health posts with a trained auxiliary nurse-midwife for medical abortion services in a phased manner, in order to increase access to medical abortion services for rural women. We also encourage the government to support scale-up of training for both female community health volunteers and auxiliary nurse-midwives.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the technical and financial support received from HRP (UNDP/UNFPA/UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction). We would also like to thank the Family Health Division (Ministry of Health and Population, Nepal) and the District Public Health Office, Rupendehi, for encouraging us to conduct this study. We are grateful to all the study participants including female community health volunteers, abortion service providers and women, for their active participation in this study.

Notes

* We do not know what happened to this group of women, but as a result of this happening we are exploring this problem in a new research collaboration.

* Only birthing centres will have the post of auxiliary nurse-midwives so as to make this possible.

References

- Ministry of Health Nepal. National Safe Abortion Policy. 2002. http://mohp.gov.np/english/files/news_events/6-2-National-Safe-Abortion-Policy.pdf

- G Samandari, M Wolf, I Basnett. Implementation of legal abortion in Nepal: a model for rapid scale-up of high-quality care. Reproductive Health. 9(7): 2012; 10.1186/1742-4755-9-7.

- Centre for Research on Environment Health and Population Activities. Increasing awareness and access to safe abortion among Nepalese women: An evaluation of the network for addressing women’s reproductive risk in Nepal program. 2009; Kathmandu.

- A Tamang, S Tuladhar, J Tamang. Factors associated with choice of medical or surgical abortion among women in Nepal. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 118: 2012; 52–56.

- C Karki, H Pokharel, A Kushwaha. Acceptability and feasibility of medical abortion in Nepal. International Journal of Gynaecology & Obstetrics. 106: 2009; 39–42.

- IK Warriner, D Wang, NT Huong. Can midlevel health-care providers administer early medical abortion as safely and effectively as doctors? A randomised controlled equivalence trial in Nepal. Lancet. 377: 2011; 1155–1161.

- J Yarnall, Y Swica, B Winikoff. Non-physician clinicians can safely provide first trimester medical abortion. Reproductive Health Matters. 17: 2009; 61–69.

- M Berer. Provision of abortion by mid-level providers: international policy, practice and perspectives. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 87(1): 2009; 58–63.

- C Harper, K Blanchard, D Grossman. Reducing maternal mortality due to elective abortion: potential impact of misoprostol in low-resource settings. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 96: 2007; 66–69.

- B Winikoff, WR Sheldon. Abortion: what is the problem?. Lancet. 379: 2012; 594–596.

- MM Lafaurie, D Grossman, E Troncoso. Women’s perspectives on medical abortion in Mexico, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru: a qualitative study. Reproductive Health Matters. 13: 2005; 75–83.

- C Rocca, M Puri, B Dulal. Unsafe abortion after legalization in Nepal: a cross-sectional study of women presenting to hospitals. BJOG. 120(9): 2013; 1075–1083. 10.1111/1471-0528.12242.

- TD Ngo, MH Park, H Shakur. Comparative effectiveness, safety and acceptability of medical abortion at home and in a clinic: a systematic review. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 89(5): 2011; 360–370.

- Ipas/Group for Technical Assistance. Capacity building of FCHVs in reproductive health referrals in six pilot districts of Nepal: Review Report submitted to Ipas. 2010; Kathmandu.

- United States Agency for International Development/New Era/Nepal Ministry of Health and Population. An analytical report on National Survey of Female Community Health Volunteers of Nepal. Kathmandu, 2007.

- United Nations Children’s Fund/Centre for Research on Environment Health and Population Activities. Baseline survey of community based newborn care package. Unpublished report, submitted to UNICEF Nepal, 2009.