Abstract

In Nepal, despite policy restrictions, both registered and unregistered brands of mifepristone and misoprostol can easily be obtained at pharmacies. Since many women visit pharmacies for abortion information, ensuring that they receive effective care from pharmacy workers remains an important challenge. We conducted an operations research study to examine whether trained pharmacy workers can correctly provide information on safe use of mifepristone and misoprostol for early first trimester medical abortion. Pharmacy workers in one district were given orientation and training using a harm-reduction approach, and compared with a non-equivalent comparison group in the second district. Overall, trained pharmacy workers’ knowledge increased substantially, but no increase was found in the comparison group. Compared to the baseline (65%), 97% of trained pharmacy workers knew up to what stage of pregnancy and how women should use mifepristone and misoprostol. A higher percentage of pharmacy workers in the intervention group (77%) compared to the comparison group (49%) were knowledgeable at follow-up about determining whether an abortion was successful, implying a need for improving this aspect of training. As many mid-level health providers run their own pharmacies and offer medical abortion pills, it is important for the government to consider training these providers and registering their pharmacies as safe medical abortion service outlets.

Résumé

Au Népal, en dépit des restrictions politiques, les marques déposées ou non de mifépristone et misoprostol peuvent être obtenues aisément en pharmacie. Puisque beaucoup de femmes se rendent dans les pharmacies pour s’informer sur l’avortement, s’assurer que le personnel leur prodigue des soins efficaces demeure un enjeu important. Nous avons mené une étude de recherche opérationnelle afin de déterminer si le personnel de pharmacie formé pouvait informer correctement sur l’utilisation sûre de la mifépristone et du misoprostol pour un avortement du début du premier trimestre. Le personnel des pharmacies d’un district a reçu des conseils et une formation pour utiliser une approche de réduction des risques, et a été comparé avec un groupe de comparaison non équivalent dans le second district. Dans l’ensemble, les connaissances du personnel formé ont nettement augmenté, mais aucune augmentation n’a été observée dans le groupe de comparaison. Par rapport à la valeur de référence (65%), 97% du personnel de pharmacie formé savait jusqu’à quel stade de la grossesse et de quelle manière les femmes devaient utiliser la mifépristone et le misoprostol. Un pourcentage plus élevé de personnel dans le groupe d’intervention (77%) que dans le groupe de comparaison (49%) connaissait le suivi pour déterminer si un avortement avait réussi, ce qui dénote le besoin d’améliorer cet aspect de la formation. Comme beaucoup de prestataires de soins de santé de niveau intermédiaire gèrent leur propre pharmacie et proposent des comprimés abortifs, il est important que les pouvoirs publics envisagent de les former et habilitent leurs pharmacies comme centres fiables d’avortement médicamenteux.

Resumen

En Nepal, pese a restricciones de políticas, tanto las marcas registradas como las no registradas de mifepristona y misoprostol son fáciles de obtener en farmacias. Dado que muchas mujeres visitan la farmacia para obtener información sobre el aborto, continúa siendo un reto importante asegurar que reciban atención eficaz del personal de farmacia. Realizamos un estudio de investigación operativa para examinar si el personal de farmacia capacitado puede proporcionar información correcta sobre el uso seguro de mifepristona y misoprostol para el aborto con medicamentos en el primer trimestre del embarazo. El personal de farmacia en un distrito recibió orientación y capacitación basadas en el enfoque de reducción de daños, y fue comparado con un grupo de comparación no equivalente en el segundo distrito. En general, los conocimientos del personal de farmacia capacitado incrementaron considerablemente, pero no se encontró ningún aumento en el grupo de comparación. Comparado con la línea base (65%), el 97% del personal de farmacia capacitado sabía hasta qué etapa del embarazo y cómo las mujeres deben usar mifepristona y misoprostol. Durante el seguimiento, se encontró que un mayor porcentaje de personal de farmacia en el grupo de intervención (77%) comparado con el grupo de comparación (49%) estaba bien informado sobre cómo determinar si el aborto había sido completo, lo cual implica la necesidad de mejorar este aspecto de la capacitación. Dado que muchos prestadores de servicios de nivel intermedio operan su propia farmacia y ofrecen medicamentos para inducir el aborto, es importante para el gobierno considerar capacitarlos y registrar su farmacia como un lugar seguro donde obtener servicios de aborto con medicamentos.

Medical abortion (MA) using a combination of mifepristone and misoprostol is safe and effective for termination of early pregnancies. Since MA can be offered in settings where surgical abortion services may not be widely available, it has the potential to increase women’s access to safe abortion. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a regimen of 200 mg of mifepristone administered orally, followed 24–48 hours later by 800 mcg of misoprostol used vaginally, buccally or sublingually for termination of pregnancies up to nine weeks (63 days) LMP. With a regimen of repeated doses of misoprostol, it is also safe and effective between 9 and 12 weeks of gestation.Citation1

Medical abortion was introduced in Nepal in 2009 on a pilot basis. Encouraged by the success of the pilot study, scaling-up of MA services throughout the country was subsequently approved. Guidelines were issued by the Family Health Division of the Ministry of Health and Population in 2009 and allowed the provision of MA by auxiliary nurse-midwives (ANMs).Citation2 The safety, efficacy and acceptability of MA provided by ANMs is now well established in Nepal.Citation3 As of September 2012, MA services up to nine weeks (63 days) LMP of pregnancy were scaled up in all public hospitals, selected private hospitals, and some NGO and private clinics throughout the 75 districts of the country. However, training of mid-level health providers (nurses and auxiliary nurse-midwives) in MA service delivery, and expansion of MA services provided by them in primary health centres and health posts has thus far been limited to 19 districts of the country.Citation4 Mifepristone and misoprostol for MA have been approved by the Department of Drug Administration and are available on prescription from accredited health care providers and clinics. Off-label or over-the-counter sale of MA tablets by pharmacies is not permitted.

Despite these restrictions, however, both registered and unregistered brands of MA pills are easily available at pharmacy retail shops. The open border with India has facilitated illegal entry of several unregistered brands of MA tablets as well as ineffective ayurvedic and other indigenous medicines that are purported to be abortifacient. Clandestine procurement and sales of such drugs by pharmacy retailers for menstrual regulation and abortion is common in Nepal. In a large-scale survey, pharmacy workers mentioned the names of 52 different allopathic medicines, 65 ayurvedic preparations and 12 homeopathic medicines which were being offered to people for menstrual regulation and/or abortion.Citation5 However, almost all of these products are ineffective or unsafe for inducing abortion.

No study has been carried out in Nepal to assess the MA dispensing practices of pharmacy workers, nor the regimens and routes of administration of misoprostol tablets they recommend. A study conducted among women receiving post-abortion care at major public hospitals in Nepal after induced abortionsCitation6 revealed that out of 527 women participating in the study, 90% had presented with vaginal bleeding and 67% with abdominal pain. Some kind of medication for abortion had primarily been used by 68% of them, and the majority had received the information from pharmacy shops. Of those who had used a medication, 84% could not name the product, while 11% cited Medabon, a brand name for a combi-pack of mifepristone and misoprostol which is registered in Nepal for medical abortion.

A Nepal-India cross-border abortion study among 1,380 women, carried out in 2010, showed that one in five women (20%) in the study sought abortion services or medications from private clinics and pharmacy shops across the border in India. About 28% of these women had experienced complications due to medicines obtained from pharmacy shops, and of these 71% had excessive vaginal bleeding associated with severe abdominal pains. Knowledge about regimens and effective routes of misoprostol administration for early first trimester abortion was poor among the Indian as well as the Nepalese pharmacy workers interviewed.Citation7

The Department of Drug Administration uses the print media to discourage illegal possession and sale of unregistered drugs by pharmacy distributors and retail shops and carries out periodic checks and raids at such shops. However, the government has not been successful in regulating clandestine market supplies and over-the-counter sales of registered and unregistered brands of MA medications. Pharmacy shops continue to act as the first contact point for many women requiring sexual and reproductive health-related information and care because of convenience and geographic accessibility: they can access medications, information and advice with relative anonymity, and at a lower cost than from the formal health sector. The success of most pharmacists and pharmacy workers in this regard seems to be due to their ability to facilitate rapid access to medications and other supplies, as well as medical information and advice, while maintaining confidentiality.Citation8

Thus, given the reach of pharmacies in the general population, and the confidence that people place in them as sources of information and medications, pharmacy workers fill a critical niche. However, they do not always provide the most accurate or effective information or dispense the correct medications to customers. In some cases, the medications they sell may be unnecessary, ineffective, or even dangerous.Citation8

The 2011 Nepal Demographic and Health Survey showed that among the women who had an abortion in the five years preceding the survey, 19% had used tablets for their last abortion. Moreover, 5% of them had obtained the tablets from a pharmacist or medicine shop.Citation9 Medical abortion services are not free at government health facilities and the fee for both manual vacuum aspiration and medical abortion (±US$ 10, or approximately 20% of average monthly family income in Nepal) is the same at all government hospitals. While the fee for medical abortion at government outreach health facilities (primary health care centres and health posts) is half the price (±US$ 5), it is still 10% of average monthly income.

Nepalese women’s knowledge about the correct medications to use for a safe abortion is low even in districts where medical abortion services have been introduced by the government. Access to information about MA – its safety, efficacy, and acceptability – is also still limited.Citation10 Ensuring that women receive effective and accurate care from pharmacists and pharmacy workers remains an important challenge, since trained professional pharmacists are few in number and do not have a consistent presence in the pharmacies. Moreover, private pharmacy providers need to overcome the challenges posed by their conflicting roles as business people and public health care providers.Citation11 Research is needed in Nepal to test strategies for collaboration between pharmacy workers and other health care providers to increase women’s access to safe abortion services and reduce unsafe abortions.

The operations research study described in this paper, using a harm reduction approach,Footnote* was designed and implemented. This study assessed the effectiveness of involving pharmacy retailers in promoting the safe use of mifepristone and misoprostol for early medical abortion. Harm reduction is an evidence-based, public health and human rights framework that prioritizes strategies to reduce harm and preserve health in situations where policies and practice prohibit, stigmatize or drive common activities underground.Citation12 In the context of the present study, the aim was to safeguard the health of women from incorrect use of MA drugs, stopping pharmacy workers from dispensing ineffective and unsafe medications, and providing them with the information they needed to advise women on correct regimens and doses. The study hypothesis was that if pharmacy workers were trained on MA regimens, they would correctly prescribe MA tablets and offer full information on MA use, including assessment of completeness of the abortion and the need for follow-up care from a trained provider in case of incomplete abortion or adverse signs and symptoms. This would, in turn, lead to a decline in the incorrect provision of MA tablets or ineffective drugs by pharmacy workers and increase referrals to safe abortion care services. Through this process, women’s safety should be improved and abortion-related complications should decrease.

Study design and methods

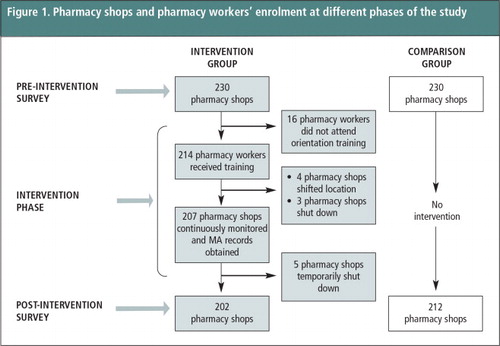

The study was an operations research study in the Jhapa district (intervention group) and neighbouring Morang district (comparison group) of eastern Nepal, using a non-equivalent comparison group design. We taught pharmacy workers in the intervention group about safe use of MA by women, using a harm-reduction approach, and studied what the pharmacy workers in the comparison group did. A pre-intervention baseline survey was carried out with 230 pharmacy shops in the intervention district and an equal number in the comparison district during June-July 2011. These pharmacy shops were selected from a list of registered pharmacy shops obtained from the zonal branch office of the Nepal Chemists and Druggists Association and through social mapping. A cluster sampling technique was used for the selection of the 230 pharmacy shops in each of the groups. The main person responsible for looking after the shop from each sampled pharmacy shop was interviewed using a structured questionnaire.

Altogether 214 pharmacies participated in the intervention out of the 230 shops from which the main pharmacy worker was interviewed. The pharmacy worker who was interviewed received two days of training in September 2011. Ten months later (July 2012), 207 of the pharmacy shop workers out of the 214 received a one-day refresher training. Four pharmacies had moved to different locations and three had closed down during that period.

The intervention aimed to improve knowledge of medical abortion, including advice on correct use of MA for early pregnancy termination by women. The topics covered were: eligibility criteria for safe MA use up to 9 weeks LMP (63 days); the recommended regimen (mifepristone 200 mg × 1 tablet orally on day 1 and misoprostol 200mcg × 4 tablets on day 2); effective routes of misoprostol administrationFootnote* (intra-vaginal, buccal or sublingual); assessment of the completeness of abortion by the woman; conditions/symptoms requiring immediate presentation to a referral hospital/facility; and the importance of a follow-up visit to a trained provider where possible for assessing abortion completeness.

Each participant attending the basic orientation training received an informational brochure on safe MA use and a set of referral vouchers to be given to women who were ten or more weeks pregnant or had experienced complications or an incomplete abortion, for referral to a registered abortion facility. The orientation training also emphasised the importance of referring women seeking abortion advice to a registered abortion facility and the illegality of ‘over-the-counter’ sales of MA tablets to women.Footnote†

An interactive meeting between the pharmacy workers and qualified abortion providers from registered abortion facilities in the district was organized during the training, in order to support and establish referral linkages.

Pharmacy workers were requested to keep a record of the number of women visiting their pharmacy shop seeking abortion advice and the number who were provided with MA tablets or referred to registered abortion centres. No such trainings or information materials were shared with pharmacy workers in the comparison group. It should be mentioned, however, that a social marketing organization had reported verbally in a meeting (and this had been mentioned often by pharmacy workers later) that they had provided orientation training on MA to pharmacy workers in several districts of Nepal in 2010, which included both the intervention and the comparison districts. Hence, we expected that some of the knowledge-related indicators would be high at the time of the pre-intervention baseline survey in both the districts.

The trained pharmacy workers in the intervention group were contacted on a monthly basis by a researcher to record the number of women or their male partners who had sought abortion advice from them, their MA dispensing practices, how many referral vouchers they had given out to women and how many women had reported that they had had an incomplete abortion or other complications with MA use.

A post-intervention survey was carried out in August-September 2012 in both the intervention and comparison groups. Of the 207 pharmacy shops in the intervention group, five were temporarily closed at the time of the post-intervention survey. Therefore, the post-intervention survey covered 202 pharmacy shops in the intervention group. To maintain a balance in the sample, 212 shops in the comparison group were selected randomly and interviewed. presents the coverage of pharmacy shops during different phases of the study.

We analysed the monthly data collected from each intervention pharmacy shop to assess the trends in the number of women/male partners seeking abortions or advice, number of referrals made and referral cards issued, the number of women/male partners who were given MA tablets, and the number of incomplete abortion or complications reported. Descriptive analysis was carried out for both the intervention and comparison groups, comparing the baseline and post-intervention data to assess the effectiveness of the intervention in enhancing pharmacy workers’ knowledge about, and dispensing practice with, MA medications. We performed statistical tests (Z test) for two independent samples (pre-and post-intervention) to assess the observed differences on the six knowledge-related indicators (gestational age under Nepal law for use of MA, correct regimens advised, time interval between mifepristone and misoprostol, effective routes for misoprostol use, assessment of completeness of abortion, and symptoms requiring immediate referral) between the pre-intervention baseline and post-intervention surveys.

Findings

Profile of pharmacy workers

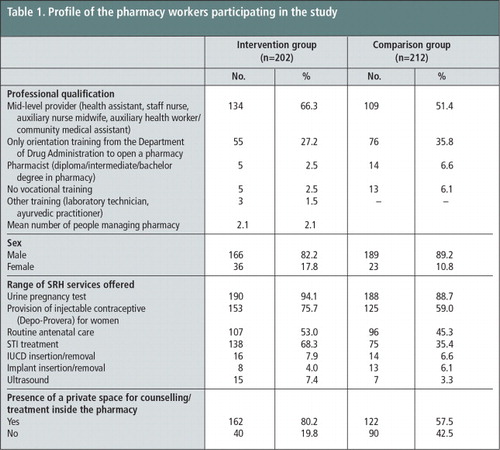

The majority of the pharmacy workers in both the intervention (66%) and comparison (51%) groups were mid-level health care providers such as health assistants, staff nurses, auxiliary nurse-midwives, and auxiliary health workers or community medical assistants. Male pharmacy workers comprised 82% of the intervention group and 89% of the comparison group.

As Table 1 shows, although dispensing prescription medications to patients and offering advice on their safe use constitute the central function of pharmacy workers, they also provide a range of sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services such as contraceptives, treatment for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and antenatal care. These SRH services and the average number of pharmacy workers looking after a pharmacy shop were generally comparable for both the treatment and comparison groups.

At baseline, a higher percentage of the pharmacy shops in the intervention group (80%) than in the comparison group (58%) had a separate space for providing counselling or examining patients and for treatment of sexually transmitted infections (68% in the intervention group and 35% in the comparison group). While the large majority of the pharmacy shops provided injectable contraceptives to women (76% in the intervention and 59% in the comparison group), less than 8% had provisions for implant or IUCD insertion and removal.

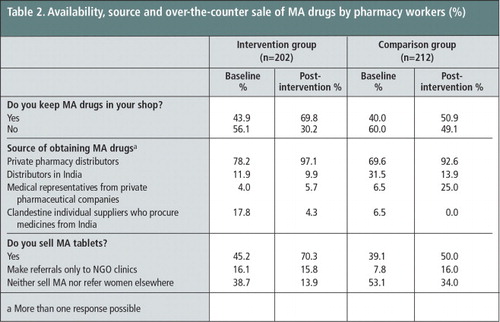

Availability and knowledge of mifepristone and misoprostol

At baseline, pharmacy workers’ knowledge about availability of mifepristone and misoprostol tablets was very high in both the treatment and comparison groups and about one-fifth kept these tablets in their shops. As Table 2 shows, the percentages of pharmacy workers in the intervention group who said they sold MA tablets increased sharply from 45% in the pre-intervention survey to 70% in the post-intervention survey, and more marginally in the comparison group from 39% to 50%. Nearly all pharmacy workers in the intervention (97%) and comparison (93%) groups at the post-intervention survey identified pharmacy distributors as their main sources of MA supplies, despite government restrictions on MA distribution in the private sector. A considerable proportion of the pharmacy workers also obtained MA tablets from distributors based in India (10% in the intervention vs. 14% in the comparison group) and medical representatives (6% in the intervention vs. 25% in the comparison group). In the intervention group, 70% of the pharmacy workers reported dispensing MA tablets over the counter. Of the remaining 30% who did not keep MA tablets in their shops, 16% said they referred anyone seeking abortion information elsewhere and 14% did not refer.

Table 2 Availability, source and over-the-counter sale of MA drugs by pharmacy workers (%).Footnotea

We collected as many as 18 different brands of mifepristone and misoprostol tablets sold in the pharmacy shops in both districts in the course of the study. Only four of these brands (Medabon, MTP Kit, Mistol, and Pregno) were registered with the Government of Nepal. Unregistered brands entered into the Nepalese market from India due to the open border and were generally sold at cheaper prices than the registered brands (Table 3).

Table 3 Brand names of mifepristone and misoprostol sold at pharmacy shops, both districts.Footnotea

Knowledge of correct use of MA drugs

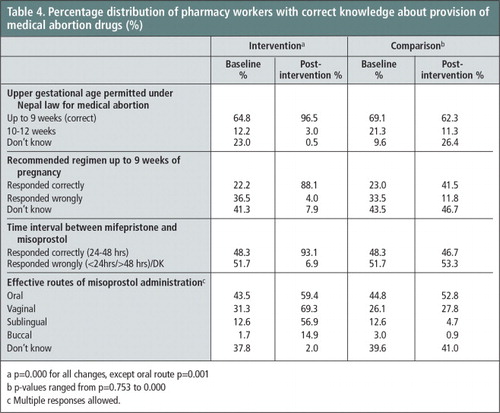

Pharmacy workers’ knowledge of the correct permitted upper gestational age for early first trimester abortion using medical abortion (9 weeks or ≤ 63 days LMP) increased sharply from 65% in the baseline survey to 97% at the post-intervention survey in the intervention group, whereas the percentage did not vary much in the comparison group. As shown in Table 4 , correct knowledge of the recommended regimens for abortion up to 63 days LMP also increased sharply in the intervention group (from 22% to 88%) as compared to the comparison group (from 23% to 41%). Similarly, there was a sharp increase in knowledge about the time interval between the two medications (24–48 hours) in the intervention group, but none in the comparison group. Likewise, increase in knowledge about intra-vaginal (from 31% vs. 69%) and sublingual routes (13% vs. 57%) of misoprostol administration was observed in the intervention group. In the comparison group the corresponding percentages were low and no marked improvement in knowledge about these two routes was observed. The percentage increases in the above knowledge indicators for the intervention group were statistically significant (p≤0.05).

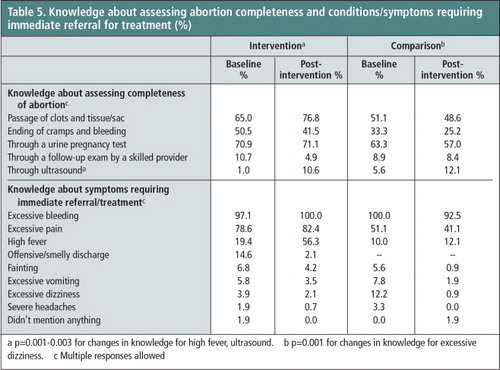

Knowledge of abortion completeness and the need for referral

Pharmacy workers’ knowledge of different indications for determining the completeness of abortion with MA use and complications requiring immediate referral for treatment did not increase significantly and in some cases it showed a decrease between the two reference periods in both the intervention and comparison group. As Table 5 shows, in the post-intervention survey 77% of the pharmacy workers in the intervention group, as against 65% in the baseline, mentioned “passage of tissue/sac” as an indication of abortion completeness. In the comparison group, only 49% cited this indication in the post-intervention survey.

Table 5 Knowledge about assessing abortion completeness and conditions/symptoms requiring immediate referral for treatment (%)FootnoteaFootnotebFootnotec.

Knowledge that women who experience excessive bleeding and excessive pain require immediate referral for treatment was already high at baseline in both groups and had increased at the end of the study, especially in the intervention group. There was also an approximately three-fold increase in the percentage of pharmacy workers in the intervention group (19% at baseline compared to 56% post- intervention) who identified “high fever” as a sign requiring immediate referral. This percentage increase is statistically significant (p≤0.001). In comparison, this knowledge remained low in the comparison group (10% vs. 12%).

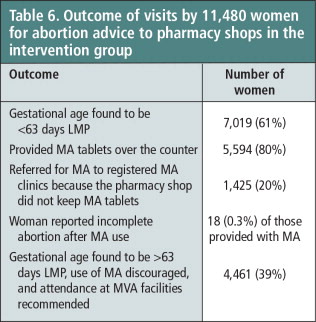

Abortion advice and provision of MA tablets by pharmacy shops

A total of 11,480 women sought abortion advice from the 207 intervention pharmacy shops during the 11 months of the study period when monthly monitoring visits to each pharmacy shop were conducted. Of the 11,480 women, pharmacy workers found 7,019 women (61%) legally eligible for MA (≤63 days of pregnancy LMP), and provided MA tablets to 5,594 of them (80%). Referrals by pharmacy workers of eligible women to clinical services for MA were made sparingly (20%) and only by those pharmacy workers who did not keep MA drugs in their shops (see Table 2). Only 18 women (0.3%) reported symptoms of incomplete abortion to a pharmacy worker, who then advised the woman to visit the nearest health facility for treatment (Table 6).

Table 6 Outcome of visits by 11,480 women for abortion advice to pharmacy shops in the intervention group.

However, some 4,461 (39%) of the women seeking abortion advice from a pharmacy shop were over nine weeks pregnant, a substantial number, and could not benefit from the use of medical abortion. They were sent to a registered clinic for manual vacuum aspiration.

Discussion and recommendations

Training of pharmacy workers in the safe use of medical abortion medications has proved useful and effective in enhancing their knowledge and the information they give women. The study has shown that compared to the baseline survey almost all pharmacy workers trained in the intervention group knew when and how to administer mifepristone and misoprostol tablets at the time of the post-intervention survey. Improvement in knowledge was more pronounced regarding recommended regimens for up to 9 weeks pregnancy; time interval between mifepristone and misoprostol administration; and non-oral routes effective for misoprostol administration. In some respects, pharmacy workers were more knowledgeable after the intervention about the passage of tissue/sac, as an indication of abortion completeness, and regarding adverse health conditions such as excessive pain, excessive bleeding and high fever that would require women to visit a health facility immediately, as compared to the comparison group.

Some of the knowledge-related indicators, such as assessing completeness of abortion process; signs/symptoms requiring immediate referral (excessive bleeding and excessive pain) were already high among the pharmacy workers at the time of the baseline in both the groups, presumably because they received MA training from the social marketing organization before our study was launched. However, the level of knowledge fell in the comparison group between the baseline and post-intervention, implying that as the period of time since the training by the social marketing group increased, pharmacy workers remembered less of what had been taught. This in turn implies that training should perhaps happen periodically, perhaps every 1–2 years, especially given the turnover of pharmacy shops and shop workers.

The study has some limitations. The baseline and post-intervention survey data were not matched according to individual respondents. We could also not ascertain how many of the women who had bought MA tablets from the intervention pharmacies used the tablets correctly nor how many actually had complete abortions. Information on incomplete abortion was based purely on the individual pharmacies’ records as maintained for this study. Trained pharmacy workers reported very few cases of incomplete abortions (18 women) considering the large number of women they served during the study period. We did not check how many women sought post-abortion care from a registered facility or hospital in the district during the study period.

Despite the emphasis paid in the orientation training on the importance of referral to safe abortion facilities and the illegality of over-the-counter sales of MA tablets to women, only a fifth of the pharmacy workers made MA referrals. Pharmacies that were already engaged in over-the-counter sales of MA tablets did not change their practice, probably because they were meeting a demand, women may have made their preference for purchasing the tablets clear, and due to the high profit margins in providing this service. The MA referrals that were made were to listed MA clinics run by non-governmental organizations, mainly by pharmacy workers who either did not sell MA tablets or did not have them in stock. Profit margins are as high as 4–5 times the procurement cost for unregistered brands of MA drugs. Local marketing agents influence pharmacy shops with different business tactics (such as “buy one, get one free” and other attractive offers if purchased in bulk) to push the unregistered brands. There are few intervention studies that have applied a harm reduction approach in engaging private pharmacies in safe MA use, and this is the first time such a study has been carried out in Nepal.

The Government of Nepal needs to formulate policies that recognize the role played by pharmacy workers in the provision of medicines for safe, early medical abortion and the prevention of unsafe abortions. Aspects of training for pharmacy workers, such as correct regimens and effective routes of misoprostol administration and self-assessment by women of abortion completeness, should improve. Such training needs to be repeated every 1–2 years to take account of new shops, new workers, and workers forgetting of what was learnt. Priority to receive government recognition (as safe MA providers) should be given to those pharmacy workers who have health backgrounds (health assistants, community medical assistants, staff nurses and auxiliary nurse-midwives) and offer other SRH services to women. There is also a need to introduce community-based education for women on MA and the importance of having an early pregnancy test and receiving early abortion care. Further research is required to assess the safety, efficacy and acceptability of MA provided by pharmacy workers from the perspectives of the women receiving MA tablets from trained pharmacy workers.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the technical and financial support from HRP (UNDP/UNFPA/UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction). We also thank the Family Health Division (Ministry of Health and Population), Nepal Health Research Council and Nepal Chemists and Drug Association for permission to conduct the study. The participation of the pharmacy workers in the study was also greatly appreciated.

Notes

* The harm reduction approach used in this study is based on research evidence that despite the legal restrictions pharmacy workers continue to provide incorrect regimens of MA tablets and other ineffective medicines to women to cause an abortion without considering the level of harm such practices could cause for women’s health and lives. Using the example of a safe syringe exchange programme for injecting drug users, the approach lays stress on safeguarding women’s health – through informed decisions by the pharmacy worker on whether or not to dispense MA tablets to women, and encouraging them to refer the woman to an appropriate clinic instead. Pharmacy workers receive education on legal provision of MA, recommended gestational limits, correct regimens for ≤ 9 weeks gestation, effective routes of administration, abortion completeness assessment criteria, follow-up check-up, and conditions requiring immediate referral.Citation12

* The Government’s instructions are to recommend vaginal, sublingual or buccal administration, in that order of priority, and this is what we informed the pharmacy workers accordingly during the training sessions.

‡ We follow a “no harm” research ethics; hence, except for reasons of grave exploitation such as human trafficking or violence, we do not report cases to the authorities.

a More than one response possible

a All manufacturers except Ohm Pharma are in India

a p = 0.000 for all changes, except oral route p = 0.001

b p-values ranged from p = 0.753 to 0.000

c Multiple responses allowed.

a p = 0.001–0.003 for changes in knowledge for high fever, ultrasound

b p = 0.001 for changes in knowledge for excessive dizziness

c Multiple responses allowed

References

- World Health Organization. Safe Abortion: Technical and Policy Guidance for Health Systems. 2nd ed, 2012; WHO: Geneva.

- Ministry of Health and Population, Family Health Division. Medical abortion scaling-up strategy and implementation guidelines. 2009; MoHP/FHD: Kathmandu.

- IK Warriner, D Wang, NT Huong. Can mid-level health-care providers administer early medical abortion as safely and effectively as doctors? A randomised controlled equivalence trial in Nepal. Lancet. 377: 2011; 1155–1161.

- T Upadhaya. Progress in the implementation of the abortion law in Nepal, Looking back 10 years, how much have we achieved in preventing unsafe abortion in Nepal. 2012; FHD/MoHP: Kathmandu. (unpublished).

- A Tamang, J Tamang. Availability and acceptability of medical abortion in Nepal: health care providers’ perspectives. Reproductive Health Matters. 13(26): 2005; 110–119.

- CH Rocca, M Puri, B Dulal. Unsafe abortion after legalization in Nepal: a cross-sectional study of women presenting to hospitals. 2013; BJOG. 10.1111/1471-0528.12242.

- Center for Research on Environment Health and Population Activities. Cross-border abortions: perceptions of private pharmacists and medicine sellers. 2010; CREPHA: Kathmandu. (unpublished).

- RK Sneeringer, DL Billings, B Ganatra. Roles of pharmacists in expanding access to safe and effective medical abortion in developing countries: a review of the literature. Journal of Public Health Policy. 33(2): 2011; 218–229.

- Ministry of Health and Population Nepal New ERA ICF International Inc. Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2011. 2012; MoHP/New ERA/ICF International: Kathmandu.

- A Tamang, S Tuladhar, J Tamang. Factors associated with choice of medical or surgical abortion among women in Nepal. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 118: 2012; 52–56.

- W Liambila, F Obare, J Keesbury. Can private pharmacy providers offer comprehensive reproductive health services to users of emergency contraceptives? Evidence from Nairobi. 2010; Kenya: Patient Education &Counselling10.1016/j.pec.2010.09.001.

- A Hyman, K Blanchard, F Coeytaux. Misoprostol in women’s hands: a harm reduction strategy for unsafe abortion. Contraception. 87(2): 2013; 128–130.