Abstract

Women’s control over their own bodies and reproduction is a fundamental prerequisite to the achievement of sexual and reproductive health and rights. A woman’s ability to terminate an unwanted pregnancy has been seen as the exercise of her reproductive rights. This study reports on interviews with 15 women in rural South India who had a medical abortion. It examines the circumstances under which they chose to have an abortion and their perspectives on medical abortion. Women in this study decided to have an abortion when multiple factors like lack of spousal support for child care or contraception, hostile in-laws, economic hardship, poor health of the woman herself, spousal violence, lack of access to suitable contraceptive methods, and societal norms regarding reproduction and sexuality converged to oppress them. The availability of an easy and affordable method like medical abortion pills helped the women get out of a difficult situation, albeit temporarily. Medical abortion also fulfilled their special needs by ensuring confidentiality, causing least disruption of their domestic schedule, and dispensing with the need for rest or a caregiver. The study concludes that medical abortion can help women in oppressive situations. However, this will not deliver gender equality or women’s empowerment; social conditions need to change for that.

Résumé

La maîtrise des femmes sur leur corps et leur procréation est une condition préalable fondamentale pour jouir de la santé et des droits sexuels et génésiques. La capacité d’une femme à interrompre une grossesse non désirée a été considérée comme l’exercice de ses droits génésiques. Cette étude rapporte les entretiens menés en Inde rurale du Sud avec 15 femmes qui ont eu un avortement médicamenteux. Elle examine les circonstances dans lesquelles elles ont choisi d’avorter et leurs opinions sur l’avortement médicamenteux. Les femmes dans cette étude ont décidé d’avorter quand de multiples facteurs, comme le manque d’appui de leur époux pour les soins aux enfants ou la contraception, des lois hostiles, des difficultés économiques, le mauvais état de santé de la femme elle-même, la violence conjugale, le manque d’accès à des méthodes contraceptives adaptées et les normes sociétales en matière de procréation et de sexualité, convergeaient pour les oppresser. La disponibilité d’une méthode facile et abordable comme les pilules abortives ont aidé les femmes à sortir d’une situation difficile, même temporairement. L’avortement médicamenteux a aussi satisfait leurs besoins particuliers en garantissant la confidentialité, en bouleversant le moins possible leur emploi du temps et en les dispensant de la nécessité de se reposer ou de trouver quelqu’un pour les soigner. L’étude conclut que l’avortement médicamenteux peut aider les femmes dans des situations oppressantes, sans toutefois garantir l’égalité des sexes ou l’autonomisation des femmes. Pour cela, il faudrait que les conditions sociales changent.

Resumen

El control que tienen las mujeres de su cuerpo y la reproducción es un prerrequisito fundamental para lograr salud y derechos sexuales y reproductivos. La capacidad de una mujer para interrumpir un embarazo no deseado es considerada como el ejercicio de sus derechos reproductivos. Este estudio informa sobre entrevistas con 15 mujeres en zonas rurales de India meridional que tuvieron un aborto con medicamentos. Examina las circunstancias bajo las cuales decidieron tener un aborto y sus perspectivas al respecto. Las mujeres en este estudio decidieron tener un aborto cuando se vieron oprimidas por múltiples factores, como falta de apoyo del cónyuge para el cuidado de los hijos o anticoncepción, suegros hostiles, penuria económica, mala salud de la mujer, violencia perpetrada por el cónyuge, falta de acceso a métodos anticonceptivos adecuados y normas sociales respecto a la reproducción y sexualidad. La disponibilidad de un método fácil y asequible, como las tabletas para el aborto con medicamentos, ayudó a las mujeres a salir de una situación difícil, aunque fuera temporaralmente. El aborto con medicamentos también cubrió sus necesidades especiales asegurando confidencialidad, causando el menor trastorno en su calendario de tareas domésticas y prescindiendo de la necesidad de guardar reposo o tener a un cuidador. El estudio concluye que el aborto con medicamentos puede ayudar a las mujeres en situaciones opresivas. Sin embargo, esto no producirá igualdad de género ni empoderará a las mujeres; para ello, es necesario cambiar las condiciones sociales.

Women’s control over their own bodies and reproduction is a fundamental prerequisite to the achievement of sexual and reproductive health and rights.Citation1 However, several studies have pointed out that women often are unable to exercise such control even when they may be able to achieve autonomy and empowerment in other spheres.Citation2,3

A woman’s ability to terminate an unwanted pregnancy has often been seen as an exercise of reproductive rights. Past studies on abortion from India have shown that the act of having an abortion may not necessarily be the exercise of reproductive choice and that women often use abortion as a desperate means to limit their family size after being unable to exercise choice in matters of sex and contraception.Citation4–8

In the past, even in settings where abortions are legally allowed, abortion methods, being surgical in nature, remained outside the control of the woman. Medical abortion, using a combination of mifepristone and misoprostol pills, or misoprostol alone where mifepristone is not available, has been seen as a technology that is safe and can make abortion less medicalized and more women-controlled.Citation9,10 Indeed, studies from Latin America have shown that in legally restrictive settings, medical abortion using misoprostol has remarkably increased women’s ability to have a safe abortion.Citation11,12

Since there is evidence that medical abortion is being increasingly used in rural India,Citation8 we undertook a study to understand rural women’s perspectives on medical abortion — the circumstances under which they opted for abortion, their reasons for choosing medical abortion, and its role in enabling them to choose the method of abortion. This paper reports findings from one part of this study.

Methodology

The study was conducted in the state of Tamil Nadu in southern India. Tamil Nadu has been seen as a pioneer for its achievements in the social sector – the state has high literacy levels among women, better maternal health indicators than most other states in India, and good health infrastructure within the public health system.Citation13 Fertility levels in Tamil Nadu are among the lowest in the country, even though use of temporary contraceptive methods is extremely low across caste and class groups.Citation14 Abortion services are available only at the district level within the public sector, however.

The Rural Women’s Social Education Centre (RUWSEC), a grassroots women’s organization to which the authors are affiliated, has been working in the northern part of the state for over three decades on issues of sexual and reproductive health and rights. As part of its work, RUWSEC also runs a reproductive health clinic which offers safe abortion services. There are a few private sector abortion providers in the towns neighbouring RUWSEC who do surgical abortions using D&C, and more recently offer medical abortion.

This qualitative study, which tried to understand women’s perspectives on safe abortion, including medical abortion, involved focus group discussions with various groups of rural and marginalized women, whose findings have been published elsewhere,Citation15 and in-depth interviews with women who had had a medical abortion. Here, we report on in-depth interviews with 15 women who had a medical abortion (MA) in RUWSEC’s clinic between September 2010 and July 2011. All the women who had MA in the clinic during this period (30 women) were invited to participate in the study; 15 women agreed. Informed consent was obtained from all 15 by the clinic’s counsellor, after which the women were contacted by the interviewers to meet at a pre-determined time and place, either in the clinic during a follow-up visit or at their home. The interviews were conducted by two of RUWSEC’s field workers, who are experienced in working with rural women on reproductive health issues. They took place two to four weeks after the abortion, using a semi-structured, in-depth interview guide that probed into the reasons for the abortion, choice of method, and abortion experience. They were conducted in the local language, Tamil, and recorded with the participants’ consent. Confidentiality was ensured by using anonymous numbered codes with the interviews. All names of respondents used here have been changed to protect anonymity. The interviews were transcribed and analysed using QSR NVivo 7 qualitative analysis software. The study was cleared by RUWSEC’s Ethics Review Committee.

For the analysis, two densely descriptive interviews were initially examined to derive inductive codes, keeping in mind the objectives. The remaining interviews were subsequently coded using constant comparison method deriving additional codes as necessary. The codes were then examined to derive themes where the inductively developed codes could be coalesced into specific themes.

Findings

Characteristics of the women

Of the 15 women interviewed, ten were aged 25–29 years, three were aged 20–24 and two were 36 and 37 years old. All the women had been to school; 11 had 8—10 years of schooling; three had post-secondary degrees or diplomas, while the oldest woman had had five years of schooling. In spite of significant education, nine of the women, including one who had qualified as a nurse, did not work outside the home. Three were agricultural wage labourers, one worked in a dress-making factory, one was a pharmacist and one was a church preacher alongside her husband.

Marriage, family and violence

All the women were married and were co-residing with their husbands, except one, who had recently separated from her husband due to domestic violence. The interviews did not probe into the circumstances of their marriages nor whether they could exercise any choice in the matter of when or who to marry.

Women’s descriptions of their marriage and family were dominated by the burden of their daily domestic routine with no time for themselves. This was a recurring theme in almost all interviews. This was compounded by the fact that even while living in large families (11 of the women lived in joint families with one or both of their husbands’ parents and sometimes their husbands’ siblings and their families), many of them reported that they were solely responsible for the majority of household chores and received little help from their husbands or other family members. This was especially true if the woman’s relationship with her marital family members was not cordial.

“There is no one to help me at home, no matter whether I am well or sick or pregnant or have had a baby recently.” (Sangeeta)

Women also shouldered the major share of care-giving responsibilities for older, ill members of the family or sick or disabled children.

“There is no one to help me. My husband supports me but he goes out to work and comes home late. My mother-in-law is diabetic and has had a leg removed – I have to look after her and also my husband, children and brother-in-law.” (Prema)

Women also felt burdened by their families’ economic hardships. While five women were dependent on their own or their husband’s daily wages, the others also found it difficult to make ends meet. In some families, the woman’s husband was the sole wage earner, with a large family dependent on him. In other cases, the husband took little responsibility for contributing financially to the family, either refusing to go to work or spending the little money earned on alcohol, leaving the woman responsible for running the household. Medical expenses were also a significant part of family expenditure. This situation caused constant worry to the women and influenced their reproductive decisions.

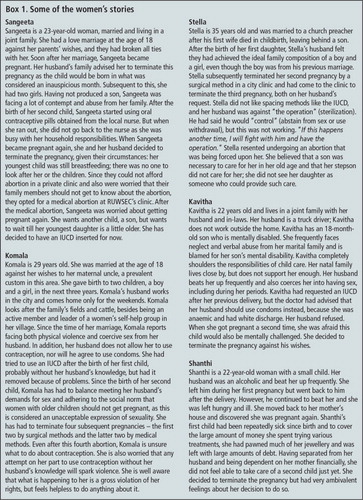

Five women faced the additional burden of domestic violence from their spouses and/or marital families. This included Kavitha, Komala, Sangeeta and Shanthi () and Malar.

“I feel bad that they treat me like a servant. Sometimes I feel I should go back to my mother’s house, but then I will be told not to come back here at all. So I continue to live here suppressing all my feelings.” (Sangeeta)

Reproductive experience

Tamil Nadu has a strong public sector maternal health and family planning programmeCitation13 and has achieved replacement-level fertility with female sterilization as the most used method of contraception.Citation14 Even in such a context, the reproductive experiences of the women in this study were marked by repeated pregnancies, frequent poor outcomes and the births of sick or disabled children.

Eight of the women had had two previous pregnancies, three had had one previous pregnancy, two had had three previous pregnancies and one each had had four and five pregnancies. Six women had only male children, five had only female children and four had children of both sexes. Malar had lost her second baby to jaundice 16 days after the birth, Shanthi’s child had been repeatedly sick since birth and Lakshmi’s elder daughter could not walk.

Repeated pregnancies went hand in hand with repeated attempts to use contraception. However, these attempts were marred by unsupportive husbands who refused to take responsibility to prevent pregnancy; problems with the methods themselves and lack of access to other suitable methods, including the refusal by health workers to provide them with a method that might better meet their needs.

Three husbands had been using contraception immediately preceding the index pregnancy. However, lack of willingness by the male partner to take responsibility resulted in inconsistent use and unintended pregnancy. Prema’s and Lakshmi’s husbands forgot to use the condom on a few occasions; Sathya’s husband developed allergies and discontinued. Sangeeta ran out of contraceptive pills and did not have time to go for more.

The other 11 women had not used contraception prior to the index pregnancy, although some had made efforts to do so in the past. However, they found that neither their families nor the system could accommodate their needs. For example, Saraswathy had intended to have post-partum sterilization after the birth of her second child, but her baby was very small and her mother advised her to wait a few months to ensure the infant survived. When she was ready to go to the health facility for sterilization, there were heavy rains and she could not go. She then thought she’d use an IUCD, but before she could do so, she discovered she was pregnant. Alamelu had also wanted to have a post-partum sterilization after her second child, but was anaemic and was therefore asked to come back in three months. By then, her husband could not take any time off work to take her to the hospital, and her mother, who had come to help her with the delivery and the baby, had also returned home, so she ended up not using any contraception. Kavitha’s request for an IUCD had been turned down. Janaki, Alamelu and Komala had previously had an IUCD but had to have it removed because they developed problems with it. None of them were offered any other suitable method afterwards. In three cases, not using contraception was not due to the women’s own volition, but their husbands not allowing them.

The women’s reproductive experiences were also significantly influenced by expectations that they adhere to norms set by family and society. The need to balance the sex composition of their families, adhere to traditional beliefs, obey societal norms regarding expressions of sexuality, all played an important role.

Additional reasons for seeking abortion

As with previous abortions, for almost all the women, multiple factors contributed to the decision to terminate the pregnancy this time too. Very often, the decision to terminate was made from a situation of lack of power and the need to negotiate their lived realities.

Poverty and financial inability to raise another child was an important reason to choose abortion, especially when husbands were the only wage earners in large joint families. Prema lived in a household of six, including two children and a mother-in-law with an amputated leg; the family was struggling to meet medical and educational expenses. After a caesarean section to deliver her second child, she started menstruating after ten months. Getting pregnant soon after, she was worried it would affect her health, so she and her husband decided to terminate the pregnancy. Latha’s family was involved in constructing a house and did not want a third child. Sangeeta felt totally unsupported by her husband’s family. Her youngest child was not even a year old, and the family was extremely poor. Others lacked adequate child care support

“I felt very sad when the doctor at the PHC told me I was pregnant. Why does God test me so? There are so many in this world without a child – they go to temples, doctors for treatment, but don’t get pregnant. Why doesn’t God give them a baby instead of to me? I told my husband this and cried.” (Sangeeta)

“Both my deliveries were by c-section. I lost my second child 16 days after her birth… It is now more than a year and a half after that. My first son is six years old. When I missed my periods, I decided I didn’t want to have a child now. I am afraid I will not be able to take care of myself after another delivery. There is no one to take care of me… I am like a ‘thanimaram’ (a lone tree).” (Malar)

For four women, lack of responsibility on the part of the husband both in preventing pregnancy and in helping with domestic and childcare responsibilities made an already difficult situation untenable, and was central to their decision to terminate the pregnancy.

“My first child has a [mental disability]. I alone take him to the physiotherapy centre for regular exercise. I am so afraid that this next child will also be like that. I want another child only after my son improves. My husband told me not to have an abortion. I said: ‘Will you take care if I have another child?’ He got angry and said: ‘You go [have an abortion]’.” (Kavitha)

Stella was the only one of the 15 who felt she was forced against her wishes to terminate this pregnancy. All the other 14 women had made the decision to terminate the pregnancy of their own volition, although the decision was made often from a situation of desperation and helplessness. Two women had not informed their husbands about the abortion – Komala, who was having her fourth abortion as she was facing sexual violence from her husband, and Shanthi, who was recently separated from her husband because of domestic violence.

The abortion experience

All the women in the study approached the RUWSEC clinic for an abortion and chose and had a medical abortion after being offered a choice between MVA and medical abortion.

Most said they had chosen the medical method based on the information provided to them at the RUWSEC clinic, as it was non-invasive, surgical instruments would not be used, no anaesthesia was needed, it was similar to a natural process, and it was seen to be less painful than surgical abortion. They were probably comparing it to their own or others’ experiences with D&C, the prevalent method of abortion in other clinics in the area. They also felt medical abortion helped them to preserve the status quo in their homes as it was the least disruptive of their daily schedules, precluded the need for any care from others, and offered a greater chance of confidentiality, which was greatly valued by the women, who saw the abortion as shameful and often did not want family members to know about it.

Cost was another important consideration in choosing the medical method. Given an already precarious financial state, most women in the study were unable to afford a surgical abortion in a private facility. Abortion services in the public sector, though free, were available only at the district level and involved spending a lot of time and energy and long waiting periods. In such a situation, a low-cost medical abortion provided at RUWSEC’s clinic was seen as an affordable solution.

“When my husband and I decided on abortion, we enquired with a private doctor in … (the nearby town). She said it would cost us 2,000 rupees (about US$ 30). We did not have so much money. There wasn’t any jewellery to pawn. If we pawned the vessels at home, my mother-in-law would come to know. I did not want her to know about this. We did not know what to do. I then spoke to my brother’s wife and she suggested I get an abortion through medicines from RUWSEC.” (Sangeeta)

Although all the women contributed significantly to their households, through domestic work, care-giving and even work outside home, most of them seemed dependent on their husbands financially when it came to seeking reproductive health care. Even women whose husbands did not support them in the use of contraception had to turn to them to pay for the abortion. All but two of the women said their husbands had given them the money. The exceptions were women who had not informed their husbands; Shanthi’s mother bore the expenses, while Komala used her own savings.

The women also listed many specific features of the services offered by RUWSEC’s clinic as important reasons for choosing a medical abortion there. The presence of a woman gynaecologist on call, a woman counsellor who explained the process and what to expect, women nurses who offered both medical and emotional support during the process of abortion, the privacy and confidentiality ensured, low cost of services, and the presence of physical facilities like beds, toilets and running water, were mentioned by almost all the women as examples of RUWSEC’s services meeting their needs.

The abortion process itself was filled with anxieties for the women, the greatest being that the pregnancy should be completely got over with, the abortion should be complete and the pregnancy expelled fully. Some women said they had feared the pregnancy would not come out and that they would need a surgical intervention. They expressed great relief when they saw the pregnancy expelled or were told by the doctor that the abortion was complete.

“I prayed to all gods that the pregnancy should come out completely with the medicines. It happened without any problems.” (Sathya)

“I was worried that the pregnancy would stay inside and my abdomen would swell up or that they would have to scrape it out of me. But nothing like that happened.” (Saraswathy)

While the women generally reported relief at the abortion being complete, they also frequently had mixed feelings, including guilt about going through an abortion. Visually seeing the pregnancy being expelled seemed to accentuate this. But they also justified to themselves the need for the abortion and often expressed a sense of “inevitability” that, given the circumstances, this was the most compelling course of action.

“When I saw those clots after the abortion, I cried in the toilet, wondering what sin I had committed and if I had destroyed a life inside me. I went home and cried too… Maybe this one was a girl and I destroyed it. My heart weeps.” (Kavitha)

“If my husband had been okay, I would not have aborted this. Have I had this abortion because of my anger against him? I am very troubled. After they inserted the tablets, I felt I was committing the sin of killing a life. But if I had not had the abortion, I would have needed money for the baby, for the delivery expenses, medical expenses. I would have caused trouble to my mother (who would have to meet these expenses). After this abortion, at one level, I feel relief, but at another, I feel what wrong did this baby do, I have killed it.” (Shanthi)

After the abortion

The main thing the women mentioned when asked about the period after the abortion was how it affected their daily domestic schedule. In a situation where they could not pass on their responsibilities to any other person, and not fulfilling their duties might be cause for violence, the fact that they could continue their household chores normally, which most women reported they could and did not have to take any time off, was seen as a very positive aspect of medical abortion. This was often juxtaposed to surgical abortion, which was seen as needing a lot of rest and care after the abortion.

“This medical method is good. If I had used any other method (like D&C), I would have had to rest in bed and follow a restricted diet like after a delivery. There would have been pain and bleeding. Since I used the medical method, I have no problems. I am happy.” (Lakshmi)

When specifically asked about how much physical rest they were able to get after the abortion, most women reported that they did not take much time off from domestic chores. This was either because someone needed special care at home, or the family was not supportive enough to take over household chores, which included caring for cattle in some households. Kavitha reported that she could not ward off her husband’s demands for sex in the immediate post-abortion period.

All of the women returned for the misoprostol 24—36 hours after the mifepristone as part of standard practice in the clinic. When asked whether they would have liked to use the misoprostol at home, all except one woman said no. While there were several reasons related to lack of physical facilities like toilets in their homes for this, the lack of support at home to handle the abortion process and the opportunity to get some rest in the facility during the abortion process were significant reasons behind this choice.

“If I use it at home, I will not get any rest. I will have to do all the household work.” (Selvi)

Future childbearing

When asked about future childbearing, very often, it seemed that the women did not by themselves have any control over their future reproductive decisions or were ambivalent because of lack of support from husband and family. Four of the women were certain they did not want any more children, while five wanted at least one more child. Three others expressed the desire to have another son. The other three were not sure whether they wanted another child or not.

“I have one son who is 10 months old. I don’t want any more children. If my husband was a good man, I could have more children. He is a drunkard. That is why I decided not to have this baby and to have an abortion… I have to get my husband out of this addiction. We both have to work and get ourselves out of debt, redeem the jewellery we have pledged. Only then can I think of another baby.” (Shanthi)

“My husband does not go to work. There is no income. I don’t want another child.” (Selvi)

When asked about future contraception, they very often expressed anxiety about getting pregnant again. It seemed they were now in the very same situation as they had been before the index pregnancy and abortion. Some women kept asking the interviewers about various contraceptive methods. Four planned to use oral contraceptive pills, six had decided on IUCDs (three of whom had an IUCD inserted on the day of the interview), two said their husbands had promised to exercise “control” or use condoms, and one wanted a sterilization. Those who could not refuse sex when their husbands wanted it and whose husbands often refused to wear condoms, chose to use methods that they themselves could control whenever possible.

While we did not explore this with them, some women seemed to indicate that they intended to use contraception without their husbands’ knowledge. One woman, Komala, mentioned that she had done so before, after three abortions, as her husband did not agree to their use of any method nor to sterilization.

“When I say to him ‘I will then keep getting pregnant and my health will be affected’, there is no answer. He will not sit down and talk about this… He does not bother. even if it means my health would be affected.” (Komala)

Discussion

The purpose of this paper was to examine the circumstances in which women chose abortion, their reasons to choose medical abortion, and the extent to which medical abortion gives women greater control. We found, however, that women’s perspectives and experiences of medical abortion or abortion per se were influenced by the negotiated circumstances of their lives and the one could not be understood without understanding the other.

Given the desperate situations of women in this study, the availability of an easily accessible and affordable method like medical abortion in a local clinic like RUWSEC’s, clearly helped the women out of a difficult situation. They found medical abortion acceptable and also appreciated that it was less disruptive of their daily schedule, that they did not need others to take over their care-giving role at home or to rest after the abortion. Yet many of them seemed set to return to the same situations that pushed them towards an abortion in the first place, and they continued to be anxious about getting pregnant again.

These findings are depressingly similar to the findings from two other studies in the same locale 10–15 years ago.Citation2,4 Yet in the intervening years, several important things have changed. In RUWSEC’s field area, women’s access to secondary education has improved, women have started working in factories in neighbouring towns, and women are increasingly taking up leadership positions in the public domain. However, if these 15 rural women are in any way representative of the local area, very little may have changed as regards gender power equations within households and in marriage, or regarding women’s realization of their sexual and reproductive health rights. Experiences like that of Komala in this study, an articulate women’s leader, well aware of her rights but a victim of regular physical and sexual violence at the hands of her husband, underscore this.

Reproductive autonomy has been defined as the right of a woman to make decisions concerning her fertility and sexuality free of coercion and violence. Lack of access to safe abortion services when a woman has an unwanted pregnancy has been seen as a serious infringement of women’s reproductive autonomy; however, the stories we report here indicate that access to safe abortion services cannot by itself assume there is reproductive autonomy. A 1999 study in Tamil Nadu by one of the authors showed that autonomy is multidimensional, and could be present in some but absent in other dimensions. Autonomy in reproductive decision-making was at that time the most elusive even for educated women and women political leaders.Citation2

What does this mean in terms of what is needed in the future? Contraception and abortion services are essential and methods like medical abortion have made abortion both easier and safer. For the women in our study, medical abortion seemed to open a door where others were closed. The fact that it was provided close to their homes in a manner that ensured quality of care while meeting their specific needs made a big difference. We must therefore continue to agitate and advocate for these technologies to be made available and accessible to women and in a manner that is sensitive to their needs. However, we cannot afford to accord less attention to the other changes needed to achieve reproductive autonomy: the possibility and the opportunity for self-determination in all matters related to sexuality and reproduction, including saying no to non-consensual sex, and refusing to bear the entire burden of pregnancy prevention. There is also an urgent need to initiate and strengthen work with men to address gender and power issues within marriage and family and bring in attitudinal and behavioural change.

Technologies may in the past have been seen as easy solutions for women’s reproductive health problems. Medical abortion has been seen as offering women greater control over the abortion process,Citation9,10 just as earlier, female condoms were posited to help women negotiate safe sex.Citation16 However, technological solutions alone are at best quick fixes. Gender equality, especially in matters related to sexual rights and reproductive autonomy, is not so easy to “fix”. In India, there is not only little effort to provide safe contraception and abortion services, but there are also no concerted efforts to address gender equality.

Globally, the ICPD Programme of Action and the Beijing Platform for Action articulated sexual and reproductive rights very clearly, and the Millennium Development Goals promised universal access to reproductive health in addition to promoting gender equality. However, 20 years later, large studies show that little has happened towards addressing any of these goals.Citation17 Smaller studies like ours reiterate this from the perspective of women’s lived experiences. How many more generations will it have to be before anything will really change?

In conclusion, women’s decision making and agency in the area of sex and reproduction are influenced greatly by their gendered existences and lived realities. When a woman is faced with an unwanted pregnancy, medical abortion offers a safe and easy solution, albeit temporarily, and needs to be made widely available within the public health system as locally as possible alongside safe contraceptive services. To deliver gender equality and women’s empowerment, however, social conditions have to change. Until then, technology such as medical abortion can only help women cope better in oppressive conditions.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the technical and financial support from HRP (UNDP/UNFPA/UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction). We thank the women who participated in the study for sharing their life stories and experiences and field workers Muniamma and Mary for conducting the interviews.

References

- UN Fund for Population Activities. ICPD Programme of Action: Adopted at the International Conference on Population and Development. Cairo, 1994.

- TKS Ravindran. Female autonomy in Tamil Nadu. Economic and Political Weekly. 31(16–17): 1999; WS34–WS44.

- R Pande. “If your husband calls, you have to go”: understanding sexual agency among young married women in urban South India. Sex Health. 8(1): 2011; 102–109.

- TKS Ravindran, P Balasubramanian. “Yes” to abortion but “no” to sexual rights: the paradoxical reality of married women in rural Tamil Nadu, India. Reproductive Health Matters. 12(23): 2004; 88–99.

- L Visaria, V Ramachandran, B Ganatra. Abortion in India : Emerging Issues from the Qualitative Studies. Mumbai: CEHAT; Abortion Assessment Project, 1997. http://www.cehat.org/go/uploads/AapIndia/qual1.pdf

- B Ganatra, S Hirve. Induced abortions among adolescent women in rural Maharashtra, India. Reproductive Health Matters. 10(19): 2002; 76–85.

- M Gupte, S Bandewar, H Pisal. Abortion needs of women in India: a case study of rural Maharashtra. Reproductive Health Matters. 5(9): 1997; 77–86.

- L Ramachandar, PJ Pelto. Medical abortion in rural Tamil Nadu, South India: a quiet transformation. Reproductive Health Matters. 13(26): 2005; 54–64.

- M Berer. Medical abortion: issues of choice and acceptability. Reproductive Health Matters. 13(26): 2005; 25–34.

- C Ellertson, B Elul, B Winikoff. Can women use medical abortion without medical supervision?. Reproductive Health Matters. 5(9): 1997; 149–161.

- N Zamberlin, M Romero, S Ramos. Latin American women’s experiences with medical abortion in settings where abortion is legally restricted. Reproductive Health. 9(1): 2012; 34.

- M Lafaurie, D Grossman, E Troncoso. Women’s perspectives on medical abortion in Mexico, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru: a qualitative study. Reproductive Health Matters. 13(26): 2005; 75–83.

- P Padmanaban, PS Raman, DV Mavalankar. Innovations and challenges in reducing maternal mortality in Tamil Nadu, India. Journal of Health Population and Nutrition. 27(2): 2009; 202–219.

- International Institute for Population Sciences Macro International. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), 2005–06, India: Key Findings. 2007; IIPS: Mumbai.

- BS Sri, TKS Ravindran. Medical abortion: understanding perspectives of rural and marginalized women from rural South India. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 118: 2012; 533–539.

- S Ray, C Maposhere. Male and female condom use by sex workers in Zimbabwe: acceptability and obstacles. Ravindran TKS, Berer M, Cottingham J, editors. Beyond Acceptability: Users’ Perspectives on Contraception. 1997; Reproductive Health Matters for WHO: London.

- S Thanenthiran, SJM Racherla, S Jahanath. Reclaiming and redefining rights ICPD+20: status of sexual and reproductive health and rights in Asia Pacific. 2013; ARROW: Kuala Lumpur. http://www.arrow.org.my/publications/ICPD+20/ICPD+20_ARROW_AP.pdf.