Abstract

Due to technological advances in antenatal diagnosis of fetal abnormalities, more women face the prospect of terminating pregnancies on these grounds. Much existing research focuses on women’s psychological adaptation to this event. However, there is a lack of holistic understanding of women’s experiences. This article reports a systematic review of qualitative studies into women’s experiences of pregnancy termination for fetal abnormality. Eight databases were searched up to April 2014 for peer-reviewed studies, written in English, that reported primary or secondary data, used identifiable and interpretative qualitative methods, and offered a valuable contribution to the synthesis. Altogether, 4,281 records were screened; 14 met the inclusion criteria. The data were synthesised using meta-ethnography. Four themes were identified: a shattered world, losing and regaining control, the role of health professionals and the power of cultures. Pregnancy termination for fetal abnormality can be considered as a traumatic event that women experience as individuals, in their contact with the health professional community, and in the context of their politico-socio-legal environment. The range of emotions and experiences that pregnancy termination for fetal abnormality generates goes beyond the abortion paradigm and encompasses a bereavement model. Coordinated care pathways are needed that enable women to make their own decisions and receive supportive care.

Résumé

En raison des progrès technologiques du diagnostic prénatal, davantage de femmes risquent de devoir interrompre leur grossesse pour une anomalie fłtale. La plupart des recherches portent sur l’adaptation psychologique des femmes à cet événement. Néanmoins, on manque de vision globale de l’expérience des femmes. Cet article rend compte de l’examen systématique d’études qualitatives sur l’expérience de femmes ayant interrompu leur grossesse pour anomalie fłtale. Dans huit bases de données, on a recherché jusqu’en avril 2014 des études révisées par les pairs, rédigées en anglais, fournissant des données primaires ou secondaires, qui utilisaient des méthodes qualitatives identifiables et interprétatives, et offraient une contribution utile à la synthèse. Au total, 4281 fichiers ont été examinés ; 14 réunissaient les critères d’inclusion. Les données ont été synthétisées en utilisant la méta-ethnographie. Quatre thèmes ont été identifiés : un monde brisé, le contrôle perdu et retrouvé, le rôle des professionnels de santé et le pouvoir des cultures. L’interruption de grossesse pour anomalie fłtale peut être considérée comme un événement traumatique auquel les femmes doivent faire face en tant qu’individus, dans leur contact avec la communauté des professionnels de santé et dans le contexte de leur environnement politico-socio-juridique. L’éventail des émotions et des expériences que suscite l’interruption de grossesse pour anomalie fłtale va au-delà du paradigme de l’avortement et englobe un modèle de deuil. Des filières coordonnées de soins sont nécessaires pour permettre aux femmes de prendre leurs propres décisions et de recevoir des soins d’accompagnement.

Resumen

Debido a los avances tecnológicos en el diagnóstico prenatal de anormalidades fetales, más mujeres contemplan la opción de interrumpir un embarazo por este motivo. Gran parte de los estudios disponibles se enfocan en la adaptación psicológica de la mujer a este suceso. Sin embargo, se carece de un entendimiento holista de las experiencias de las mujeres. Este artículo reporta una revisión sistemática de estudios cualitativos de las experiencias de las mujeres con la interrupción del embarazo por anormalidad fetal. En ocho bases de datos, se realizó una búsqueda hasta abril de 2014 de estudios revisados por pares, redactados en inglés, que reportaron datos primarios o secundarios, utilizaron métodos cualitativos identificables e interpretativos, y ofrecían una contribución valiosa a la síntesis. En total, se examinaron 4281 estudios; 14 reunían los criterios de inclusión. Los datos fueron sintetizados utilizando meta-etnografía. Se identificaron cuatro temáticas: un mundo destrozado, perdiendo y volviendo a ganar control, el role de profesionales de la salud y el poder de culturas. La interrupción del embarazo por anormalidad fetal puede considerarse un suceso traumático que las mujeres experimentan como personas individuales, en su contacto con la comunidad de profesionales de la salud, y en el contexto del ambiente político-socio-jurídico. La variedad de emociones y experiencias que genera la interrupción del embarazo por anormalidad fetal va más allá del paradigma de aborto y abarca un modelo de pesar. Se necesitan opciones de servicios coordinados que les permitan a las mujeres tomar sus propias decisiones y recibir atención con apoyo.

In England and Wales in 2013, pregnancy termination for fetal abnormality represented 1% of all terminations.Citation1 As antenatal screening techniques develop and maternal age rises, thus increasing the risk of abnormalities,Citation2 more women are likely to be diagnosed with fetal abnormality and face the prospect of ending their pregnancy. Research indicates that terminating a pregnancy for fetal abnormality is a complex decision,Citation3 which can have long-term psychological consequences such as depression, post-traumatic stress and complicated grief for women and their partners.Citation4–9 Grief reactions following this event have been likened to those experienced in other types of perinatal loss such as stillbirth or neonatal death.Citation10–12 Nevertheless, termination for fetal abnormality is distinct in that parents choose to end the pregnancy. This element of choice places this phenomenon at the centre of ethical debates, which have implications for women’s experiences. The first debate relates to abortion rights and to whether abortion harms women’s mental health. However, the most comprehensive and recent reviews have concluded that abortion does not harm women’s well-being.Citation13–15 The second debate relates to the question of eugenics and is illustrated by deliberations about the timeframe and the medical conditions for which pregnancies can be terminated, which have occurred in the past decade.Citation16 The third debate focuses on health professionals’ attitudes about termination for fetal abnormality and their right to conscientious objection.Citation17

Current research on women’s responses to pregnancy termination for fetal abnormality is limited by a focus on quantitative measurement of psychological outcomes. Two systematic reviews,Citation18,19 published in 2011, provide useful insights but do not address women’s experiences holistically. These limitations warrant a review of qualitative studies about the experience of terminating a pregnancy for fetal abnormality. This article describes the first systematic review of qualitative studies about women’s experiences of pregnancy termination for fetal abnormality. The review aims to provide an evidence base for clinical practice and policy making in the hope that it will help professionals provide the best possible care. Although the rationale for this review was rooted in a political, cultural and clinical context specific to England and Wales, the review examines women’s experiences across seven different countries and, in doing so, broadens the relevance of its findings.

Methods

This systematic review is a meta-ethnography. The data were selected and analysed following the guidelines outlined by Noblit and Hare.Citation20 Eight electronic databases were searched up to April 2014 () to identify qualitative studies of women’s experiences of pregnancy termination for fetal abnormality: Academic Search Elite, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Embase, Maternity and Infant Care, MEDLINE, PubMed, PsychINFO and PsychARTICLES. A manual search was conducted on relevant authors and reference sections of key articles. Search terms included: pregnancy termination, induced abortion, therapeutic abortion, fetal abnormality, fetal anomaly, adaptation, adjustment, experiences, qualitative research, qualitative studies, and interview.

To be included, studies had to report findings from primary or secondary data about women’s experiences and be based on identifiable and interpretative qualitative methods of analysis (e.g. grounded theory). Purely descriptive qualitative studies were excluded. Studies also had to be peer-reviewed, be written in English to avoid translation bias, and offer a valuable contribution to the synthesis. The last criterion differed from others because it involved a subjective appraisal; however this is in line with meta-ethnographic guidelines.Citation20 Still, to enhance the review’s validity, study quality was assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme,Citation21 a framework successfully used in other meta-ethnographies.Citation22–24 Each study was evaluated on ten questions covering methodological and ethical considerations, clarity and transparency of the analysis, and its contribution to knowledge. Agreement about the articles to include in the review was high. Any divergence of opinion was resolved through discussion. Although the review’s focus was on women’s experiences, studies containing men’s or health professionals’ accounts were included provided that women formed a substantial part of the sample and that the analysis of women’s accounts was clearly identifiable.

Data were synthesised using meta-ethnography.Citation20 This approach centres on interpretation of qualitative findings rather than aggregation, and thus is comparable to the qualitative methods of the studies it synthesises.Citation25 It involves analysing studies (participants’ quotations and themes identified by the study’s authors) in relation to one another to determine whether the themes relate to or refute each other. The analysis then involves creating new themes, which are compared across studies, and from which an interpretative framework (line of argument) is generated.Citation20,25,26 The analysis was conducted by Author 1 and cross-validated by Author 2. Both authors were in agreement that the themes and interpretative framework were rooted in the data and provided a meaningful interpretation of women’s experiences.Footnote*

Findings

Altogether 4,281 records were identified. Of those, 4,142 were excluded and 40 duplicates removed. Full texts of 99 articles were assessed; 85 were excluded because they did not fit the inclusion criteria, were mixed with cases of other perinatal losses or continuing pregnancy, mostly did not cover termination for fetal abnormality, or the full text was unavailable. Fourteen studies, published between 1997 and 2013, were selected for review (). Five were conducted in the USA, four in the UK, and one each in Brazil, Viet Nam, Israel, Sweden and Finland. Studies originated from the fields of anthropology, nursing, obstetrics, public health, social work and sociology.

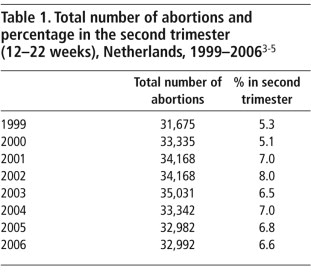

Table 1 Study characteristicsCitation27–40, Footnotea,b

The synthesis generated four themes: a shattered world, losing and regaining control, the role of health professionals, and the power of cultures. Throughout this paper, the terms ‘baby’ and ‘child’ have been used because they reflect the language used by participants and convey that, in most cases, the pregnancy was desired.

A shattered world

Emotional earthquake

For many women, pregnancy termination for fetal abnormality is akin to an emotional earthquake that shakes their core beliefs and requires reconstruction. Women describe intense physical and emotional pain, with some mentioning “want[ing] to die”.Citation30 The psychological pain is usually the most difficult to overcome,Citation27 particularly when feticide (in utero injection causing fetal demise) is involvedCitation29,34 and women feel or witness their baby’s last movements on screen.Citation29,34 They also find it challenging to labour/recover in wards with women who had positive pregnancy outcomes.Citation31 The brutal transition between the state of pregnancy and non-pregnancy contributes to feelings of devastation.Citation27,33 For women giving birth to their baby after a medical termination, the transition between “saying hello and goodbye”Citation27 within the same encounter is inconceivable. Many women are stunned and unprepared for making decisions surrounding the baby’s birth, whether to see or hold the baby, what type of funeral to have, and whether to take the baby’s photo or hand/foot prints.Citation33 The magnitude of the discrepancy between pregnancy expectations and outcome only furthers women’s distress.Citation31

Following the termination, women contemplate their loss, often yearning for their child long after the termination.Citation31 The mourning process is ongoing and women accept that this is a “lifelong affair”Citation28 with the pain subsiding but never disappearing entirely. Women lose the immediate future they had imagined, having often gone to great lengths to prepare for the baby’s arrival.Citation30,31 A loss of reproductive self-esteem is also observed, with some women feeling that they have failed to bear a healthy child, and failed themselves and those around them.Citation31

Assault on the self

Pregnancy termination for fetal abnormality also represents an “assault” on the selfCitation34 and undermines women’s sense of security.Citation27,30 Many women start their pregnancy with a (false) sense of security that “their baby would be fine”,Citation30 and the pregnancy normal.Citation30,38 Learning of the abnormality represents a “loss of innocence”, which women long to recapture and generates a heightened sense of vulnerability.Citation28 Some struggle with their values and spiritual beliefs over the decision to terminate.Citation27,29–31,38 Terminating the pregnancy also has profound consequences for women’s self-identity as mothers, as it implies choosing between becoming the “mother of a disabled child or a bereaved mother”.Citation30 Some women blame themselves for the abnormality, while others question their moral courage for choosing not to have a child with impairment.Citation30,31 Childless women experience the additional difficulty of being denied the social status of motherhood.Citation30 Women also question their bodies which some hold responsible for creating an imperfect childCitation31 or healing too quickly compared to the mind.Citation27,30 The return of menstruation signals the physiological readiness to be pregnant, often in contrast with how women feel emotionally.Citation27 Incongruence between body and mind is also experienced with lactation, which women find particularly difficult.Citation31

Ambivalence

Ambivalence is manifest in the decision to terminate the pregnancy as it involves conflicting feelings. It is a subtle balancing act between the baby’s prospects and potential quality of life, and the woman’s, her partner’s and children’s needs.Citation27–29,31,38 It often carries high levels of uncertainty as many diagnoses are based on probabilities.Citation34 For many women, the decision to end the pregnancy is a decision they wish they never had to make.Citation38 However, the distress at having to make the decision can co-exist with relief at being given the opportunity to make it,Citation27,29,31 sparing this child a life of suffering and sparing other children having to care for an impaired sibling. Ambivalence is also apparent in women’s emotional relationship to the baby, moving between the need to protect and distance themselves, and “fighting love for their baby”.Citation27 Some Vietnamese women consider the baby’s abnormality to be the result of family members’ immoral behaviour and welcome the opportunity to prevent the birth of an impaired child. Others feel guilty at robbing their child of a life and fear that the baby’s soul may return to haunt them, potentially hindering their reproductive future.Citation31 Women are also conflicted between their need for time to gather and process information and the difficult experience of continuing “giving life while thinking about taking it”.Citation34

Losing and regaining control

The paradox of choice

Most women depict their decision-making as a choice between two “alternatives, both of which are unpleasant”Citation30 and taking the decision to terminate because the situation was hopeless.Citation36,39 They feel this is not a real choice, and that their agency is limited.Citation30,39 This is particularly true for women who had to obtain authorisation to terminate, as was the case in Brazil when the study was conducted.Citation29 This is also the case in Israel where state approval is required beyond 24 weeks’ gestation.Citation34 Yet most women feel that their decision is right. For many, it is the first (and only) parental decision they get to make for this baby,Citation27–29,31 and one of the only ways they can exert control. This may explain the sense of achievement reported in some studies.Citation29

Regaining control

Many women feel, to various degrees, powerless, with a lack of control over emotions and grief. They are unprepared for the magnitude and duration of the painCitation27–31,36 and the “rollercoaster”Citation27,38 of emotions experienced post-termination. Attempts to regain control over the situation include controlling their social environment by limiting contact with othersCitation27,40 and self-disclosure.Citation27,28,30,37 These strategies are both for self-protection and attempts at controlling emotions. Others reclaim control through their decisions post-termination, e.g. organising the baby’s funeral.Citation33,40 Women also mention keeping emotional control during subsequent pregnancy through the development of “emotional armour”.Citation28

Surviving the ordeal

The aftermath of the termination is akin to “the day after” (the earthquake). Women are in shock, but feel very much alive. Some consider it an ultimate test of strength of characterCitation29 and of the relationship with their partner.Citation28 They are acutely aware that the decision to terminate is theirs alone, even if in consultation with their partner.Citation29,31 Casting themselves as survivors, women describe going through “the hardest thing they ever did”Citation27 with bravery and resilience.Citation28,29 Some report growing stronger as a result of the terminationCitation29,40 and discovering new strengths.Citation39 Following the termination, women engage in the laborious task of rebuilding their internal world. Deriving meaning is important for some and positive growth is one way to impart meaning to their experience.Citation40 Putting the experience to good use (e.g. sponsoring charities), redefining life priorities and addressing unresolved issues all contribute to feelings of empowerment and growth.Citation40 Women also find solace in “renewed empathy”Citation27 towards others and the consolidation of family ties.Citation27,29 Another pregnancy is generally soothing but can be bitter-sweet, another illustration of ambivalence.Citation28,40 Women consciously lower their expectations of a new pregnancy and seek information in an attempt to prepare themselves for potential setbacks.Citation28 A new pregnancy is seen as a leap of faith requiring courage and determination, but which is eventually rewarding: “no guts, no glory”.Citation28

The role of health professionals

Information as empowerment

Women value timely, clear and unbiased information that they can understand about the abnormality, the termination procedure and what to expect post-termination.Citation31,35,36 Advice on how to disclose the end of the pregnancy to others,Citation37 including their own children, and information about what to expect emotionally long-term are also important but these are seldom provided by health professionals. Some women report having to source information themselves,Citation38,39 which some resent,Citation39 while others consider it an integral part of their coping process.Citation40

Information provision can be seen as a way to empower women to make informed decisions.Citation33,38 A lack of information not only generates distress,Citation31 but maintains women in a state of passivity and uncertainty, and leaves them feeling unprepared for the termination and its aftermath.Citation33 In comparison, women welcome information enabling them to make decisions that are right for them. Choice of termination method is a good example,Citation28,35 in that women are able to reconcile the experience with their own values and beliefs.Citation35 Some women value the opportunity to give birth after a medical termination, create bonds and have their baby blessed, while others opt for surgical termination in a bid to distance or protect themselves as they fear “never want[ing] to let [the baby] go”.Citation35

Empathy and compassion

Above all, women value empathic and compassionate care. They are grateful when health professionals acknowledge that their pregnancy is wanted, and care for them in a non-judgmental way.Citation35,36 They derive comfort from health professionals’ acts of kindness, which at times can stretch beyond the usual doctor — patient boundaries.Citation40 Receiving respect and dignity for themselves and their baby is critical.Citation36,40

The lack of aftercare

Women repeatedly point to a lack of aftercare. They feel “unsupported”, almost abandoned,Citation36,39,40 which furthers their distress. To fill this vacuum, some women seek support from counselling servicesCitation40 but these come at a financial cost.Citation36 Others turn to support groups to share their storyCitation36,39,40 and reciprocate support, which some find therapeutic.Citation40 Given the lack of aftercare, memories of encounters with caregivers during the termination can have a long-lasting influence on how women cope.Citation40 However, although the feeling of isolation women experience post-termination is partly due to a lack of aftercare, it also results from women’s inability to share their story due to the stigma surrounding pregnancy termination for fetal abnormality.

The power of cultures

Stigma and secrecy

The stigma attached to abortion generates an atmosphere of secrecy and shame, and many women report a fear of being judged. The Israeli study refers to termination for fetal abnormality as a “taboo” and describes women facing a “wall of silence”.Citation34 This leads women to censor themselves,Citation27,28,30,38 only sharing part of their story,Citation34,37,39 labelling their experience a miscarriage or only disclosing the full story to a selected few.Citation37 Partial disclosure can be a double-edged sword, protecting women from potentially hurtful reactions, while hindering healing through the inability to access support.Citation37 By only sharing part of their story, women may be unable to fully process their loss, undermining their identity as a bereaved mother. Hence, some women choose full disclosure — they want people to know.Citation37 Generally women who have chosen full disclosure report positive experiences.Citation30,37

Disenfranchised grief

Whether women disclose their full story or not, women’s grief is disenfranchised as their loss is generally not sanctioned by society. Because theirs is a “chosen loss”,Citation31 and “nobody knew the baby”Citation33 women feel inadequate in expressing their grief. In Viet Nam, women are encouraged to forget about their baby and the location of the grave is often kept secret from them.Citation31 The language used to define termination for fetal abnormality also matters. Although women agree that the procedure is an abortion, they want their experience to be differentiated from abortions for non-medical reasons.Citation36 Some find the terms “abortion” and “termination” harshCitation37 and would rather call it “therapeutic premature delivery”Citation29 or compare it to switching off a life support machine.Citation27 The inadequacy of language to describe their experience further alienates women as they are unable to effectively communicate their story. This inadequacy is also noticeable in the absence of terminology, e.g. in Israel, where there is no word for feticide.Citation34 Terminology to refer to the baby is another example; some women find terms such as “fetus” hurtful.Citation40 Others, however, would rather not “think of it as a baby,”Citation33 or feel they have “lost a pregnancy more than a baby”.Citation32

Cultural landscape

Social context greatly impacts women’s experiences. Polarised debates on abortion result in women being stigmatised and feeling like social outcasts.Citation27,28,30 Abortion laws are also influential as they dictate the timing and medical conditions for which pregnancies can be terminated.Citation29,34 In the USA, abortion is legal but operates differently across states. Women may have to travel to a different state to access screening or abortion services.Citation38 In Viet Nam, feticide is not performed prior to inducing labour, resulting in some babies being born alive.Citation31 Conversely, to some women, feticide is the most traumatic part of the termination.Citation29,34 Whether the cost of the procedure is covered by public healthcare systems also influences the outcome, since it may lead to unequal access to services. In the USA, many women struggle to obtain financial cover from their insurance providers.Citation38 Yet, many women may feel pressurised to terminate their pregnancy because of society’s strong support for antenatal screening.Citation34 Furthermore, this covert pressure takes place within political and social environments generally advocating the inclusion of people with disabilities, which some women find confusing.Citation30

The environment in which women are cared for and the doctor—patient relationship also influence women’s experience. In Viet Nam, women’s deference to clinicians prevents their asking questions and some women describe feeling ashamed of involving physicians in an “unpleasant experience”.Citation31 This implicit power imbalance influences the level of control women feel they exert. In contrast, in other medical cultures women are encouraged to ask questions and, where possible, participate in their care.Citation33,35

Finally, the legacy of the past also contributes in shaping women’s experiences. The Vietnamese policy “of enhancing the quality of its population” linked to a rise in birth defects from Agent Orange after the Viet Nam war, may be an attempt to obliterate the past.Citation31 Similarly, early 20th century eugenicist policies in Finland may still influence the way antenatal diagnosis is perceived, and the way women experience terminations for fetal abnormality and are cared for, as health professionals now emphasise parental autonomy.Citation39

Discussion

This meta-ethnography indicates that pregnancy termination for fetal abnormality affects women as individuals, patients and social beings. Women’s experience can be understood within a multi-dimensional framework (micro, meso, macro); each dimension corresponding to women’s interactions with themselves, the health community and their environment.

The micro dimension centres on women’s internal world. Women’s experience is, first and foremost, an intimate experience. Across very different countries, the experience of terminating a pregnancy for fetal abnormality is traumatic, a finding consistent with the quantitative literature. It is akin to an existential crisis, a metaphor utilised in the Vietnamese studyCitation31 and the literature about decision-making following a diagnosis of fetal abnormality.Citation3 However, it is also an illustration of resilience and, for some, an opportunity for growth, a finding in line with some bereavement studies.Citation41

The meso dimension focuses on women’s experience of care during and after pregnancy. Providing women with information enables them to make informed decisions and cope with the termination long-term. Information provision can also be empowering, enabling women to regain control over a situation many feel they have no control over. This review, however, suggests that although women generally receive information on the abnormality and, to a lesser extent, the procedure, they mostly feel unprepared for its emotional toll. Health professionals would need to find ways to support women post-termination and reassure them that their pain is part of a normal grief response. Finally, many women find the structure and duration of care and the care pathway lacking or fragmented. The lack of aftercare is particularly manifest in this review, a finding supporting existing research.Citation4,42

Finally, the macro dimension focuses on the laws, policies, and historical background, which determine but are also the result of societal attitudes towards pregnancy termination for fetal abnormality. Whether or not these terminations are permitted, the timing and medical conditions for which they are performed, the quality of clinical practice, the attitudes of caregivers, societal expectations of women as mothers, as well as attitudes towards abortion and disability, collectively form the landscape within which women experience pregnancy termination for fetal abnormality. As societies send conflicting messages to women, extolling the acceptance of disability while encouraging antenatal screening, many women may feel unable to share their story and thus feel isolated and stigmatised.

Implications

Acknowledging the complexity and range of women’s experiences

Pregnancy termination for fetal abnormality is both a type of abortion and a unique form of bereavement, which is inconsistent with the clinical and societal paradigm of abortion when pregnancy is unwanted. Pregnancy termination for fetal abnormality also differs from other perinatal losses which do not arise from a woman’s decision, and from other types of bereavement in that the loss is not usually socially sanctioned. As pregnancy termination for fetal abnormality is a relatively new phenomenon, women (and health professionals) are unable to draw on previous knowledge. Furthermore, technological developments in screening mean that women are constantly faced with new questions which have yet to receive normative responses.Citation43 Thus, it is essential that health professionals and policy makers conceptualise and acknowledge the complexity of this phenomenon and the range of emotions it generates.

The need for structured, coordinated and woman-centred care pathways

As many women in the studies reviewed found their care pathway fragmented and, at times, lacking, it is important that health professionals develop, manage and implement better structured and coordinated care pathways. Women need information about the termination itself, the decisions to be made before and after it, and the emotional fallout in the short- and longer-term. Women should be supported throughout the process, including post-termination if need be. Care also needs to address psychological issues that are particularly relevant to pregnancy termination for fetal abnormality, such as self-blame and guilt.Citation44 These care pathways need to be woman-centred and reflect women’s preferences in terms of their clinical care (e.g. termination method), how to deal with the baby post-termination and the terminology used to refer to their situation. As part of coordinated care pathways, health professionals should consider early referral to support groups, or other organisations that may fill some of the gaps in the care they provide, and/or to therapy services if it seems warranted.

Law and policy issues

The Brazilian study provides a clear reason to legalise termination in cases of lethal fetal abnormality, while the Israeli study illustrates the importance of removing obstacles to accessing a procedure most women already find difficult to contemplate. Finally, the polarisation of the debate surrounding pregnancy termination for fetal abnormality (and more generally abortion) in the countries where it is raging leads to stigmatisation and harms women. Although these observations are specific to the countries from which the reviewed studies originated, the implications are relevant globally.

Limitations

This review has several limitations. It covers only articles written in English, excluding potentially insightful research. The USA and UK were over-represented, and women in the studies originating from high-income countries were predominantly white, middle-class, and well-educated. This bias has been observed in other studies.Citation4,8 Nevertheless in the USA, this profile may accurately reflect the population who undergo these terminations, given that by law, states are not required to cover “elective” abortion. This results in many women relying on private insurance providers to cover the cost of the termination.Citation45 Lastly, none of the studies was longitudinal, therefore it is not possible to ascertain how women fared over time.

Conclusion

This review brings together important insights into a topic that has been largely dominated by quantitative research. We hope that our recommendations will enable women’s voices to be better heard in an often politically charged debate and result in their needs being addressed more appropriately. It is noteworthy that only a relatively small number of studies were identified as relevant to the topic and considered to be of sufficient quality to be included in the review. The review also indicates that there remains a dearth of research in some areas, for example, on women’s experience of care and whether the care they receive meets their needs. It would also be beneficial to examine health professionals’ understanding of women’s experiences as this would help to identify potential knowledge needs. Given the importance of the cultural context, future research should also examine to what extent women feel pressurised to experience and express their grief in a way that matches society’s idea of motherhood.Citation43 Finally, owing to the paucity of evidence, research into interventions to support women during and post-termination is required.

Notes

* Further methodological details are available from the corresponding author.

a Sample comprised women presenting for termination because of fetal abnormality. All other studies are based on women who had undergone termination.

b Sub-sample of the Hunt study but analysed independently.

References

- Department of Health. Report on abortions statistics in England and Wales in 2013. June 2014. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/report-on-abortion-statistics-in-england-and-wales-for-2013.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. RCOG statement on later maternal age. June 2009. http://www.rcog.org.uk/what-we-do/campaigning-and-opinions/statement/rcog-statement-later-maternal-age.

- M Sandelowski, J Barroso. The travesty of choosing after positive prenatal diagnosis. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing. 34(3): 2007; 307–318. 10.1177/0884217505276291.

- H Statham, W Solomou, JM Green. When a baby has an abnormality: a study of parents’ experiences. 2001; Centre for Family Research, University of Cambridge: Cambridge.

- V Davies, J Gledhill, A McFadyen. Psychological outcome in women undergoing termination of pregnancy for ultrasound-detected fetal anomaly in the first and second trimesters: a pilot study. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 25(4): 2005; 389–392. 10.1002/uog.1854.

- A Kersting, M Dorsch, C Kreulich. Trauma and grief 2–7 years after termination of pregnancy because of fetal anomalies – a pilot study. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynecology. 26(1): 2005; 9–14. 10.1080/01443610400022967.

- MJ Korenromp, GC Page-Christiaens, J van den Bout. A prospective study on parental coping 4 months after termination of pregnancy for fetal anomalies. Prenatal Diagnosis. 27(8): 2007; 709–716. 10.1002/pd.1763.

- MJ Korenromp, GC Page-Christiaens, J van den Bout. Adjustment to termination of pregnancy for fetal anomaly: a longitudinal study in women at 4, 8, and 16 months. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 201(2): 2009; 160.e1–160.e7. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S000293780900393710.1016/j.ajog.2009.04.007.

- A Kersting, K Kroker, J Steinhard. Psychological impact on women after second and third trimester termination of pregnancy due to fetal anomalies versus women after preterm birth – a 14-month follow up study. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 12(4): 2009; 193–201. 10.1007/s00737-009-0063-8.

- CH Zeanah, JV Dailey, MJ Rosenblatt. Do women grieve after terminating pregnancies because of fetal anomalies? A controlled investigation. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 82(2): 1993; 270–275.

- KA Salvesen, L Oyen, N Schmidt, UF Malt. Comparison of long-term psychological responses of women after pregnancy termination due to fetal anomalies and after perinatal loss. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 9(2): 1997; 80–85. 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1997.09020080.x.

- K Keefe-Cooperman. A comparison of grief as related to miscarriage and termination for fetal abnormality. OMEGA – Journal of Death and Dying. 50: 2004–2005; 281–300. 10.2190/QFDW-LGEY-CYLM-N4LW.

- VE Charles, CB Polis, SK Sridhara. Abortion and long-term mental health outcomes: a systematic review of the evidence. Contraception. 78(6): 2008; 436–450. 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.07.005.

- B Major, M Appelbaum, L Beckman. Abortion and mental health: evaluating the evidence. American Psychologist. 64(9): 2009; 863–890. 10.1037/a0017497.

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Induced abortion and mental health: a systematic review of the mental health outcomes of induced abortion including their prevalence and associated factors. December 2011. http://www.nccmh.org.uk/reports/ABORTION_REPORT_WEB%20FINAL.pdf.

- Amendment of law relating to late abortion. United Kingdom Parliament Publications. December 2007, Column 301. http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld200708/ldhansrd/text/71212–0012.htm.

- S Strickland. Conscientious objection in medical students: a questionnaire survey. Journal of Medical Ethics. 38(1): 2011; 22–25. 10.1136/jme.2011.042770.

- JR Steinberg. Later abortions and mental health: psychological experiences of women having later abortions – a critical review of research. Women’s Health Issues. 21(3 Suppl.): 2011; S44–S48. 10.1016/j.whi.2011.02.002.

- C Wool. Systematic review of the literature: parental outcomes after diagnosis of fetal anomaly. Advances in Neonatal Care. 11(3): 2011; 182–192. 10.1097/ANC.0b013e31821bd92d.

- GW Noblit, RD Hare. Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing qualitative studies. 1988; Sage: Newbury Park (CA).

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Checklists. Oxford, 2014. http://www.casp-uk.net/#!casp-tools-checklists/c18f8.

- R Campbell, P Pound, C Pope. Evaluating meta-ethnography: a synthesis of qualitative research on lay experiences of diabetes and diabetes care. Social Science & Medicine. 56(4): 2003; 671–684. 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00064-3.

- A Malpass, A Shaw, D Sharp. Medication career or moral career? The two sides of managing antidepressants: a meta-ethnography of patient’s experience of antidepressants. Social Science & Medicine. 68(1): 2009; 154–168. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.068.

- SA Munro, SA Lewin, HJ Smith. Patient adherence to tuberculosis treatment: a systematic review of qualitative research. PLoS Medicine. 4(7): 2007; e238.http://www.plosmedicine.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pmed.004023810.1371/journal.pmed.0040238

- N Britten, R Campbell, C Pope. Using meta-ethnography to synthesise qualitative research: a worked example. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy. 7(4): 2002; 209–215. 10.1258/135581902320432732.

- S Atkins, S Lewin, H Smith. Conducting a meta-ethnography of qualitative literature: lessons learnt. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 8: 2008; 21. 10.1186/1471-2288-8-21.

- SH Bryar. One day you’re pregnant and one day you’re not: pregnancy interruption for fetal anomalies. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing. 26(5): 1997; 559–566. 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1997.tb02159.x.

- P Rillstone, SA Hutchinson. Managing the reemergence of anguish: pregnancy after a loss due to anomalies. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing. 30(3): 2001; 291–298. 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2001.tb01547.x.

- L Ferreira da Costa L de, E Hardy, MJ Duarte Osis. Termination of pregnancy for fetal abnormality incompatible with life: women’s experiences in Brazil. Reproductive Health Matters. 13(26): 2005; 139–146. 10.1016/S0968-8080(05)26198-0.

- JL McCoyd. Pregnancy interrupted: loss of a desired pregnancy after diagnosis of fetal anomaly. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 28(1): 2007; 37–48. 10.1080/01674820601096153.

- T Gammeltoft, MH Tran, TH Nguyen. Late-term abortion for fetal anomaly: Vietnamese women’s experiences. Reproductive Health Matters. 16(31 Suppl): 2008; 46–56. 10.1016/S0968-8080(08)31373-1.

- RH Graham, K Mason, J Rankin. The role of feticide in the context of late termination of pregnancy: a qualitative study of health professionals’ and parents’ views. Prenatal Diagnosis. 29(9): 2009; 875–881. 10.1002/pd.2297.

- K Hunt, E France, S Ziebland. ‘My brain couldn’t move from planning a birth to planning a funeral’: a qualitative study of parents’ experiences of decisions after ending a pregnancy for fetal abnormality. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 46: 2009; 1111–1121. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.12.004.

- RD Leichtentritt. Silenced voices: Israeli mothers’ experience of feticide. Social Science & Medicine. 72(5): 2011; 747–754. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.12.021.

- J Kerns, R Vanjani, L Freedman. Women’s decision making regarding choice of second trimester termination method for pregnancy complications. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 116(3): 2012; 244–248. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.10.016.

- N Asplin, H Wessel, L Marions. Pregnant women’s experiences, needs, and preferences regarding information about malformations detected by ultrasound scan. Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare. 3(2): 2012; 73–78. 10.1016/j.srhc.2011.12.002.

- EF France, K Hunt, S Ziebland. What parents say about disclosing the end of their pregnancy due to fetal abnormality. Midwifery. 29(1): 2013; 24–32. 10.1016/j.midw.2011.10.006.

- LM Gawron, KA Cameron, A Phisuthikul. A qualitative exploration of women’s reasons for termination timing in the setting of fetal abnormalities. Contraception. 88(1): 2013; 109–115. 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.05.062.

- K Koponen, K Laaksonen, T Vehkakoski. Parental and professional agency in terminations for fetal anomalies: analysis of Finnish women’s accounts. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research. 15(1): 2013; 33–44. 10.1080/15017419.2012.660704.

- C Lafarge, K Mitchell, P Fox. Women’s experiences of coping with pregnancy termination for fetal abnormality. Qualitative Health Research. 23(7): 2013; 924–936. 10.1177/1049732313484198.

- SM Engelkemeyer, SJ Marwit. Post-traumatic growth in bereaved parents. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 21(3): 2008; 344–346. 10.1002/jts.20338.

- MC White-Van Mourik, JM Connor, MA Ferguson-Smith. Patient care before and after termination of pregnancy for neural tube defects. Prenatal Diagnosis. 10(8): 1990; 497–505. 10.1002/pd.1970100804.

- JL McCoyd. Discrepant feeling rules and unscripted emotion work: women coping with termination for fetal anomaly. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 79(4): 2009; 441–451. 10.1037/a0010483.

- B Nazaré, A Fonseca, MC Canavarro. Trauma following termination of pregnancy for fetal abnormality: is this the path from guilt to grief?. Journal of Loss and Trauma. 19(3): 2014; 244–261. 10.1080/15325024.2012.743335.

- JL McCoyd. Women in no man’s land: the abortion debate in the USA and women terminating desired pregnancies due to fetal anomaly. British Journal of Social Work. 40(1): 2010; 133–153. 10.1093/bjsw/bcn080.