Abstract

Among the Millennium Development Goals, maternal mortality reduction has proven especially difficult to achieve. Unlike many countries, China is on track to meeting these goals on a national level, through a programme of institutionalizing deliveries. Nonetheless, in rural, disadvantaged, and ethnically diverse areas of western China, maternal mortality rates remain high. To reduce maternal mortality in western China, we developed and implemented a three-level approach as part of a collaboration between a regional university, a non-profit organization, and local health authorities. Through formative research, we identified seven barriers to hospital delivery in a rural Tibetan county of Qinghai Province: (1) difficulty in travel to hospitals; (2) hospitals lack accommodation for accompanying families; (3) the cost of hospital delivery; (4) language and cultural barriers; (5) little confidence in western medicine; (6) discrepancy in views of childbirth; and (7) few trained community birth attendants. We implemented a three-level intervention: (a) an innovative Tibetan birth centre, (b) a community midwife programme, and (c) peer education of women. The programme appears to be reaching a broad cross-section of rural women. Multilevel, locally-tailored approaches may be essential to reduce maternal mortality in rural areas of western China and other countries with substantial regional, socioeconomic, and ethnic diversity.

Résumé

Parmi les objectifs du Millénaire pour le développement, la réduction de la mortalité maternelle s’est révélée particulièrement difficile à réaliser. Contrairement à de nombreux pays, la Chine est dans les temps pour atteindre ces objectifs au niveau national, avec un programme d’institutionnalisation des accouchements. Néanmoins, dans les zones rurales, défavorisées et ethniquement diverses de la Chine occidentale, les taux de mortalité maternelle demeurent élevés. Pour réduire la mortalité maternelle en Chine occidentale, nous avons élaboré et appliqué une approche à trois niveaux dans le cadre d’une collaboration entre une université régionale, une organisation à but non lucratif et les autorités sanitaires locales. Avec une recherche formative, nous avons identifié sept obstacles à l’accouchement en milieu hospitalier dans un comté tibétain rural de la province de Qinghai : 1) difficultés pour se rendre à l’hôpital ; 2) impossibilité pour les parents accompagnants de se loger à l’hôpital ; 3) coût de l’accouchement en milieu hospitalier ; 4) obstacles linguistiques et culturels ; 5) manque de confiance dans la médecine occidentale ; 6) divergences dans la conception de la naissance ; et 7) manque d’accoucheuses communautaires formées. Nous avons appliqué une intervention à trois niveaux : a) un centre de naissance tibétain novateur, b) un programme de sages-femmes communautaires et c) l’éducation des femmes par les femmes. Le programme semble atteindre un vaste segment représentatif des rurales. Des approches à plusieurs niveaux et adaptées au contexte local peuvent être essentielles pour réduire la mortalité maternelle dans les zones rurales de Chine occidentale et d’autres pays avec une diversité régionale, socio-économique et ethnique substantielle.

Resumen

Entre los Objetivos de Desarrollo del Milenio, ha resultado particularmente difícil lograr la reducción de la mortalidad materna. A diferencia de muchos países, China está bien encaminada para cumplir estos objetivos a nivel nacional, mediante un programa para institucionalizar partos. No obstante, en las zonas rurales, desfavorecidas y con diversidad étnica de China occidental, las tasas de mortalidad materna continúan siendo altas. Para reducir la mortalidad materna en China occidental, formulamos y aplicamos una estrategia de tres niveles como parte de una colaboración entre una universidad regional, una organización sin fines de lucro, y autoridades de salud locales. Por medio de investigación formativa, identificamos siete barreras para el parto hospitalario en un condado rural tibetano de la Provincia de Qinghai: (1) dificultad para viajar a un hospital; (2) los hospitales carecen de alojamiento para las familias acompañantes; (3) el costo del parto hospitalario; (4) barreras idiomáticas y culturales; (5) poca confianza en la medicina occidental; (6) diferencias en los puntos de vista sobre el parto; y (7) pocos asistentes de parto comunitarios capacitados. Realizamos una intervención de tres niveles: (a) un innovador centro de parto en Tibet, (b) un programa comunitario de parteras profesionales, y (c) educación de las mujeres por pares. El programa parece estar llegando a una gran variedad de mujeres rurales. Posiblemente sea esencial aplicar estrategias en múltiples niveles, adaptadas a nivel local, para reducir la mortalidad materna en las zonas rurales de China occidental y en otros países con considerable diversidad regional, socioeconómica y étnica.

Among the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), progress on achieving MDG 5, which seeks to reduce the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) by three-quarters between 1990 and 2015, and to improve access to reproductive health, has been especially difficult. Although better access to contraception and declining fertility rates in many countries have lowered the lifetime risks of maternal mortality,Citation1 observers predict that few countries will achieve the MDG 5 target by 2015.

The reasons for the slow progress on MDG 5 are varied. One reason is that the MMR has increased in eastern and southern Africa due to HIV/AIDS.Citation2 A second reason is the complexity of providing universal antenatal and delivery care. Low-income women, those from marginalized groups, and women in remote rural areas often lack high quality, accessible delivery care when they need it.Citation3–5 Deliveries occur on their own schedule and complications can be hard to predict. The low status of women in many parts of the world also increases the chance of potentially risky pregnancies (e.g. pregnancy at very young ages or at high parity), inadequate nutrition before and during pregnancy, and poor or non-existent antenatal and delivery care.Citation6–8

In contrast to many countries, China has made considerable progress in reducing maternal mortality and the nation as a whole is on target to meet MDG 5 by 2015.Citation1 Remarkably, the nationwide MMR declined an average of 5.7% per year between 1990 and 2011, a pace which is three times higher than the average decline for developing countries in this period (p.1153).Citation1 China’s strategy has focused on “institutionalization” of childbirth, i.e. ensuring that all deliveries occur in hospitals. To this end, China has implemented media campaigns, improvements in maternal-child health infrastructure, oversight, staff training, and referral networks at township and lower-level hospitals.Citation9,10 Subsidies to pregnant women and hospitals for institutional deliveries have been available in many areas.Citation9,11,12 Other strategies, such as community midwife programmes, have been discouraged in order to concentrate resources on hospital deliveries.Citation9 Institutionalization of delivery and subsidies for hospital delivery have been employed in other countries, such as India,Citation13 but with more limited success in reducing maternal mortality.

By 2008 in most regions of China, institutional delivery was virtually universal.Citation11 However, despite this overall success, poor rural areas, particularly in western China, continue to have lower rates of hospital deliveries and higher MMRs.Citation9–11,14–17 Although maternal mortality has declined in all regions, it remained significantly higher in 2010 in the western region than in other areas: 46.1 per 100,000 live births, compared with 29.1 for the central region and 17.8 for the east.Citation18 Post-partum haemorrhage remains the most common cause of death,Citation18 suggesting that women with emergencies do not receive medical help in time. Less frequent use of hospitals (and higher maternal mortality) in remote western counties may be due to poor infrastructure, scarce human resources, long travel distances to reach hospitals, lack of access to caesarean section and blood transfusions in some local hospitals, and reluctance of women, particularly from ethnic minorities, to deliver in hospitals because of discomfort with the delivery practices used.Citation11

Thus, although institutionalization of deliveries has accomplished a great deal in most of China, it is unlikely to lower maternal mortality in poor, under-resourced rural western regions to levels found elsewhere in China in the next several years. The persistence of higher maternal mortality ratios in western China suggests that a single universal approach may not be sufficient in all areas of a country as diverse as China. In this paper, we argue for an alternative approach for western China — a multi-level maternal health programme — and describe its implementation in Rebkong (Chinese: Tongren) County, a predominantly Tibetan area in Qinghai Province, China. The programme was designed and implemented by Tso-ngon (Chinese: Qinghai) University Tibetan Medical College (TUTMC) in collaboration with the international non-profit organization Tibetan Healing Fund (THF), and local health authorities. The approach overcomes a number of barriers to high quality local delivery care in rural areas of western China. We also believe that it can serve as a model for poor, rural, hard-to-reach and ethnic minority areas elsewhere in the region, e.g. other rural areas of western China, Nepal, northern India, southeast Asia and Bangladesh – as well as middle- and low-income countries in other regions.Citation5,13,19,20

In this paper, we first describe the rural area where we have been working and outline the results of formative research we carried out there. Then we outline our approach to reducing maternal deaths there, briefly summarize results from an evaluation, and conclude by considering our approach in a larger context.

Qinghai Province and Rebkong (Tongren) County

Qinghai Province is in western China on the Tibetan Plateau and is part of the traditional Tibetan region of Amdo. It is one of the poorest provinces in China with a per capita GDP in 2003 of US$1814 for urban areas and US$483 for rural areas.Citation21 In 2000, Qinghai’s MMR of 139 was exceeded in China only by MMRs in neighbouring Xinjiang (161) and the Tibetan Autonomous Region (467).Citation14 The MMR declined to 104 in Qinghai by 2005, but it remained considerably higher, especially in rural areas, than the rate of 20 per 100,000 in Shanghai, Beijing, and Jiangsu, and Zhejiang provinces.Citation15

The population of Qinghai province is ethnically diverse: in 2010, 53% were Han, 24% Tibetan, 15% Hui, and 8% other groups.Citation22 The majority of rural residents in 2000 in the province were Tibetans and other non-Han ethnic groups, with Tibetans being the largest group.Citation23 Cities and towns, where hospitals and health care are more common, were predominantly inhabited by Han residents.Citation23 The rural Tibetan population make their living either as farmers or as nomadic herders. The nomadic population, in particular, has to travel long distances over dirt paths and mountainous terrain to reach health care. Health care is often difficult to access even for farmers in rural villages because of distance, difficulty of travel, and lack of transportation.

Rebkong (Chinese: Tongren) County, in which the programme described below is located, is in Malho (Chinese: Huangnan) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, one of five Tibetan autonomous prefectures in Qinghai. The County incorporates about 3,250 square miles. In 2010, its population was about 85,000,Citation24 the majority of whom were Tibetan. Although MMRs are not available for prefectures and counties, the poor rural population of Malho Prefecture is likely to have a significantly higher MMR than Qinghai Province as a whole. The officially reported total fertility rate for Rebkong County in 2000 was 1.2 births per woman.Citation25 Even accounting for the possibility of under-reporting, this rate is quite low for such a poor, rural setting and reflects China’s birth planning policy.

Barriers to improving maternal health

To understand the reasons underlying higher maternal mortality rates in the region, a research team from the Tso-ngon (Chinese: Qinghai) University Tibetan Medical College (TUTMC) in Qinghai Province and the international non-profit Tibetan Healing Fund (THF) conducted formative research to identify barriers to improving maternal health pre-, during, and post-partum. Formative research involves collecting qualitative and/or quantitative data and synthesized them to aid in the design and implementation of an intervention.Citation26 Formative research is particularly useful for developing interventions which are culturally and geographically appropriate.

The formative research in this project was based on the example of the three-delays model,Citation27 which provides a framework for considering barriers to delivery and post-partum care. The TUTMC-THF research team members know the Rebkong area well and one team member, a Tibetan obstetrician-gynaecologist, practised for several years in the local county hospital. Other team members are Tibetan doctors experienced in health care for Tibetans and other populations.

The team conducted a sample survey in the area in 2003 (n = 280 women aged 15–49 in a random sample of households) on antenatal and delivery practices, other health behaviour, and socioeconomic status. The sample included women in two predominantly Tibetan townships. A structured, close-ended questionnaire was administered by Tibetan health personnel to each sample member. Survey methods and results are described in detail elsewhere.Citation28 The results showed that 96% of women reported delivering their most recent child at home, and only 27% reported seeing a health worker at any time during pregnancy. Deliveries were almost always attended by the women’s mother, sister or other female relative. These findings are consistent with a study in another part of Qinghai (Yushu Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture) in 2004, in which 99% of women delivered at home without a trained birth attendant.Citation21 In addition to the survey, the research team visited the Rebkong region and talked informally with women and their families, health care providers, and local women’s leaders. They also visited local hospitals and talked with women recovering from delivery and their families, as well as medical staff.

Based on this research and the team members’ prior experience, the TUTMC-THF team identified seven barriers to maternal mortality reduction through China’s institutionalized delivery programme in the Rebkong area. First, travel to the hospital for antenatal exams and especially for delivery is difficult for rural Tibetan women, particularly nomads and those in villages far from major towns and cities. Health care is available in the township health centre, prefecture hospitals, and cities — facilities which are located at considerable distance from rural villages and are accessible to villagers or nomads only by long trips on foot or by donkey/horseback, yak, tractor, motorcycle, or occasionally car.

Second, hospitals typically lack accommodation for families who accompany women and remain with them until discharge, to avoid multiple trips and to provide care and meals. Hospitals often have multiple patient beds in a single room, no space for families, and no separate family accommodation.

Third, delivery at a hospital can be costly: transport to and staying at a hospital for delivery is expensive, even though hospital costs are partly subsidized by the government. Patients have to pay hospital bills, the costs of medicine, and treatment fees, as well as family lodging and food.

Fourth, there are often language and cultural barriers between Tibetan women and non-Tibetan health care providers. Most doctors and nurses are neither Tibetan nor speak much Tibetan. Rural Tibetan women often speak some Chinese, but are more comfortable speaking Tibetan. Language, education, and social class differences can lead to significant misunderstanding and miscommunication, which may further complicate the delivery process.Citation29 The Tibetan cultural prohibition against men’s involvement with pregnancy and childbirth also discourages women from hospital delivery because male doctors are common. Like all groups, Tibetans have their own cultural practices surrounding the birth of a baby, including prayers by Buddhist monks and lay people. Hospitals often have little respect for these customs and lack space and the proper environment for these practices.

Fifth, rural Tibetans often have limited confidence in the skills and training of doctors in hospitals and clinics practicing western medicine. They have more experience with Tibetan medicine and doctors and with the holistic basis of Tibetan medicine, which seeks to balance elements in the body and is part of their own cultural tradition.

Sixth, most Tibetan women view pregnancy and childbirth as a normal process (not an illness or emergency) and see hospitals as places to treat illness and emergencies. Thus, going to a hospital to deliver a baby is seen as counter-intuitive. This belief is also reported in rural Shanxi Province, where it has been identified as a barrier to hospital delivery,Citation19 and it may be common in other rural areas of China. Rural Tibetan women also have little formal education and limited access to information about maternal and child health and infectious disease.Citation28

Finally, there are very few trained birth attendants available outside of hospitals, and no traditional midwives in Tibetan culture. Births at home are typically assisted by untrained female family members.Citation21,28,29 Village doctors have little training in pregnancy and childbirth. Hence, local knowledge about how to handle obstetrical emergencies, when they occur, is limited.

Many of these barriers are prevalent in other poor rural areas in the region. For example, in rural Shanxi Province and in Nepal, financial limitations, transportation, and lack of faith in the quality of hospital care are reported to be important road blocks to safe delivery care.Citation5,19,20 Rural ethnic minority women in Sichuan Province, China, also reported social cultural barriers similar to those identified by the TUTMC-THF team: hospitals’ lack of facilities for family members, difficulty carrying out cultural traditions surrounding birth, and the presence of male doctors.

Meeting local needs: the three-level approach

To surmount the barriers described above, the TUTMC-THF team designed a comprehensive maternal health programme in Rebkong (Tongren) County, known as the three-level approach to Health Care for Rural Women and Children. The approach was designed both to improve local maternal health and to field test a multi-level strategy for delivery of improved delivery care to rural Tibetan and other women in western China. The approach operates at the county, community and individual level to deliver integrated, safe, culturally-appropriate, low-cost services, including: (1) an innovative maternity and health care facility to complement current government health facilities at the county level; (2) recruitment of, and midwifery training for, community health workers and women willing to become midwives at the local level; and (3) peer education for rural Tibetan women about pregnancy, delivery, and women’s and children’s health at the individual level. Each component is described below.

County level: Tibetan Natural Birth and Health Training Centre

In collaboration with the Rebkong County and the Prefecture Health Bureau, the TUTMC-THF team planned and built the Tibetan Natural Birth and Health Training Centre (Birth Centre) in Rongwo (Chinese: Longwu), Rebkong County. Funding for the construction of the Birth Centre was provided by Tibetan Healing Fund (THF), which solicits charitable contributions internationally to support health initiatives in the Tibetan region. The land was donated by the current Birth Centre director and THF contributed hundreds of hours of volunteer labour to build the Centre, which opened in July 2009. In 2013, funding from THF also facilitated the expansion of the Birth Centre to include an additional 14 rooms to accommodate the increasing demand for delivery services at the Centre.

The Birth Centre aims to attract Tibetan and other women who would not normally deliver in a hospital, especially those at risk of complications. It is a highly unusual type of health care facility for China, where virtually all medically-attended deliveries occur in standard hospital ward settings. In contrast, the Birth Centre is based on the birth or birthing centre model,Citation30,31 combining a home-like atmosphere with high quality ob-gyn care. It offers a linguistically and culturally Tibetan environment, a skilled, all-female staff of biomedically-trained Tibetan obstetricians and midwives, modern clinical facilities and equipment, and Tibetan medicine care and facilities. Pregnant women and families can stay in modest home-like suites – including heated family sleeping platforms, quilts and linens, cooking facilities, bathrooms, and showers – during their time at the Birth Centre.

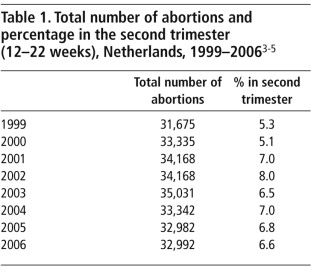

As indicated in , the Birth Centre provides six main types of services to individual patients: delivery care, antenatal care, post-delivery care for women and their infants, gynaecological services, family planning, and health education. Delivery care consists of natural childbirth without the use of medications; cases that involve surgery or serious complications are referred to the nearby prefecture hospital. Post-delivery care includes post-partum care for women, newborn care, breastfeeding support, and initial newborn immunization – with referral to the County Disease Control Centre for later immunizations. Gynaecological services include a broad range of women’s health concerns, including diagnosis and treatment of infections, HIV prevention education and management, and assistance with menstrual or menopausal problems. Health education on maternal and child care and prevention is included as a component of each service. Conditions that cannot be treated adequately are referred to the prefecture hospital and/or the Tibetan medicine hospital. Information on referrals has been collected at the Birth Centre only since the beginning of 2014.

Source: Tibetan Birth Centre administrative records, tabulated for this paper.

presents the number of services delivered annually at the Birth Centre. Each visit is counted separately and when multiple services are delivered at the same visit, each of those is also counted separately. Thus, a woman with two antenatal care visits, one of which included health education, is recorded in the table twice for antenatal care and once for health education.

The cost of health services is partially subsidized regardless of where they occur, but the unsubsidized portion of the cost is lower at the Birth Centre (approximately 500 RMB) than at the prefecture hospital (≥1500 RMB). As shown in , by the end of 2013, more than 2,000 deliveries had taken place at the Birth Centre – all were live births. The Birth Centre also coordinates other activities of the three-level approach, described below.

It is difficult to determine what proportion of women of reproductive age in Rebkong County who need obstetric and gynaecological services have been reached, because of the difficulty of obtaining accurate local population estimates. If the population of Rebkong County is roughly 85,000, as indicated above, we estimate that they include approximately 22,000 women aged 15—49. Based on officially published age-specific fertility rates for 2000,Citation24 we then estimate that the average annual number of births in the County would be approximately 900–1,100. These estimates suggest that many of the births in the County are taking place at the Birth Centre.

The numbers in also provide a measure of the Birth Centre’s success in meeting other reproductive health needs. The number of visits for these services have increased substantially during the five-year period. For example, the number of health education visits increased dramatically from 3,274 in the first full year of operation to more than 6,000 in 2013. The increase in the visits for reproductive health services other than delivery reflects both a greater number of women receiving Birth Centre services and an increasing number of repeat visits by patients.

Community level: health worker recruitment and training

At the community level, the goal of the three-level approach is to develop a network of health workers with basic obstetric training to provide care to women who deliver at home. In rural areas, health care is provided by a village doctor or other community health workers trained at the county level and able to provide basic primary care. Despite the absence of a midwifery tradition, older women with children sometimes act as informal birth attendants. The Health Worker Recruitment and Training programme recruits village doctors, community health workers, informal birth attendants, and leaders of local women’s committees to attend workshops and receive basic training in antenatal, delivery, post-natal care, and children’s health. The majority of trainees are rural women with children of their own, but very little (if any) training in pregnancy-related care, child health care or health promotion. Many participants are well-known in their communities because they participate in village women’s associations, which are local government groups responsible for representing women’s interests. The TUTMC-THF team, and particularly the director of the Birth Centre, regularly make visits throughout the county and have attempted to recruit at least one person from each village, town, and local area (for nomadic populations) in the county.

The TUTMC-THF team, headed by the Birth Centre director and her colleagues, hold regular training workshops for participants on topics including recognizing signs and symptoms of potential complications, safe birth practices, managing routine deliveries, and referrals to the Birth Centre or township-level health facilities for complex cases. Training takes place at the Birth Centre and involves practical, hands-on experience, as well as visual teaching aids (e.g. videos and pictorial diagrams), rather than theoretical or book-based learning. To date, 334 health workers and midwives (one from each of 334 villages and towns) have been trained in a total of five multi-day workshops. Funding and volunteer hours for the health worker training and development of materials have been provided by the TUTMC-THF team. In addition to the didactic component of the multi-day training classes, the training serves to strengthen the relationships and referral network between the Birth Centre staff, the midwives, and communities in which the midwives live and work. Subsequent to training, it is not uncommon for midwives and health workers to contact Birth Centre staff directly via mobile phone when they encounter a problem or need information or guidance. If the midwives cannot solve the problem in the village, the referral system allows them to refer women quickly to the Birth Centre. An additional 300 undergraduate and graduate Tibetan medicine students from TUTMC have participated as students in these training workshops. Through this workshop and practical experience, students become qualified to conduct similar basic obstetric training workshops for midwives, health workers, and village women in the future.

Individual level: peer education

At the individual level, the goal is to educate individual women about basic health care, including pregnancy, using a peer education model. The midwives, health workers, and village residents trained in the Birth Centre workshops described above are asked to return home and educate individual women in their community, using the TUTMC-THF-developed Maternal and Child Health Education Handbook. The handbook uses Tibetan-style drawings and pictures to provide basic information about pregnancy, perinatal care, immunization, family planning, nutrition, and common illnesses. Trained health workers visit women in their homes and discuss these issues together, using the book as a guide. By providing health knowledge, this one-on-one education empowers women to make health decisions for themselves and their families, e.g. how to spot problems in advance, when to seek care, and what type of health care is needed. Roughly 5,000 copies of the handbook are now in use by health workers and women in rural communities.

Birth Centre survey

In September-October 2012, we conducted a survey of a randomly selected sample of Tibetan women who had delivered at the Birth Centre between June 2011 and July 2012 (n = 114) and women who resided in the same communities but who had not delivered at the Birth Centre (n = 108). In addition, four focus group discussions were conducted with women of reproductive age living in surrounding communities. Respondents were asked about socioeconomic characteristics, pregnancy history, delivery experiences and perceptions, and knowledge and use of the Tibetan Birth Centre by friends or family members. Women who had used the Birth Centre were asked about their experiences there. Below we present summary findings of this survey. Detailed findings are available in separate papers.Citation32,33

The socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of the women in the two samples were very similar, suggesting that the Birth Centre is fulfilling its goal of attracting a broad range of Tibetan women. The only significant differences between the two groups were parity (Birth Centre users were more likely to be lower parity: χ2 = 66.43, p < 0.000) and preference for delivery in a health care facility (Birth Centre users were more likely to prefer delivery in a health care facility: χ2 = 55.79, p < 0.002). For both samples, mothers and mother-in-laws were most likely to decide where a woman should deliver her baby (around 60% for mothers and mothers-in-law combined), followed by husbands (14–20%). Women delivering at the Birth Centre were more likely to be involved in the decision themselves compared to other women (26% vs. 14%; p = 0.02). The results highlight the importance of reaching family members, as well as pregnant women, through the peer education programme.

Women delivering their babies at the Birth Centre overwhelmingly expressed satisfaction, with 98% of women reporting being ‘highly satisfied’ or ‘satisfied’ with their experience and 95% of women indicating that they would refer a family member or friend to the Birth Centre in the future. Further input from open-ended survey questions indicated that women valued the comfort and flexibility offered by the Birth Centre in birthing practices and post-natal care. For example, women who had delivered previously at the hospital mentioned a preference for the Birth Centre in terms of the large rooms with heated beds, the choice of delivery position (e.g. on knees rather than on back), and the presence of their families during the birthing process. Additionally, adherence to cultural practices such as chanting scriptures during the birth, placing amulets and Tibetan thangkas on the wall, and placing a butter pill in the mouth of the newborn were all practices that they appreciated about their experience at the Birth Centre.

Expansion of the three-level approach programme and its impact

With the Birth Centre recently reaching its five-year anniversary and with increasing demand and use of its services, the Birth Centre is now financially self-sustaining. Hundreds of health workers and peer educators who have been trained — and participate in occasional refresher training — continue to conduct health education in their home villages. The level of staff commitment has been extraordinary, with high retention and low turnover rates for personnel. Thus, we expect that the Birth Centre services and the other activities based at the Centre in Rebkong will continue for many years.

The successes of the three-level approach are notable in quantitative terms (i.e. increased utilization, number of health workers trained, attended deliveries and other services used), but also in improving the perceptions of maternal health care and delivery care options in this rural, ethnic minority population. The focus group results and ongoing discussions with local community members indicate that the approach used is associated with positive change for the local Tibetan community. The Director of the Birth Centre was seen by focus group participants and local leaders as a well-respected, charismatic leader and a highly-competent physician working with a team of qualified female health care providers to provide high quality services that respect local customs and traditions.

A limitation of this pilot study is that we cannot assess whether the intervention has reduced maternal mortality and morbidity rates in the Rebkong area. To detect a change in the MMR would require implementing the intervention in a much larger population. Although maternal morbidity is more frequent and thus requires a smaller sample to measure, a large scale survey would, nonetheless, be needed to collect adequate data. Although studies have demonstrated that population-based survey data can be used to measure maternal morbidity reliably in populations with a high proportion of medically-assisted deliveries,Citation34,35 the quality and consistency of morbidity self-reporting may be lower among poorly educated rural women in this region, who typically do not receive medical care during delivery. Thus, we have not attempted to measure change in maternal morbidity.

Discussion

The three-level approach described above is an alternative model of delivery care to address the unique maternal health needs of rural, hard to reach, and marginalized groups and to combat persistent disparities in maternal mortality rates within lower- and middle-income countries. This approach complements existing maternal mortality reduction strategies in China and other countries in three ways. First, through community- and individual-level efforts, this model addresses the barriers that Tibetan women (and women from other disadvantaged groups) often face when giving birth. Second, this approach illustrates the utility of a collaborative partnership between an international, non-profit organization (Tibetan Healing Fund) and a provincial university (Tso-ngon University Tibetan Medical College (TUTMC)) and prefectural and county government agencies that have extensive knowledge of barriers to reducing maternal mortality and how to overcome them. Lastly, this model illustrates the importance of ‘bottom-up’ approaches to complement existing ‘top-down’ approaches, particularly in regions or populations in which the standard approach is less effective.

The implementation of national policies and construction of health care facilities to encourage skilled birth attendance may be more effective in reducing maternal mortality if accompanied by additional individual- and community-level efforts such as those proposed here. This perspective is supported by a recent Partnership for Maternal-Newborn-Child Health/WHO reportCitation36 on the importance of multi-level interventions in improving maternal, newborn, and child health. Although China has made significant progress toward meeting the maternal mortality reduction goals of MDG5, continued mortality decline in some regions may require complementary approaches that address cultural and logistic barriers. The three-level approach provides a model for overcoming these barriers both within China and in other countries.

The three-level approach was intended as a first step in developing a more holistic and sustainable approach to reducing maternal mortality in Rebkong County. The types of maternal health problems described for this area are prevalent in rural communities throughout the Tibetan region, elsewhere in rural China, and in other countries.Citation5,13,19,20 We are currently assessing the maternal health needs of other areas in Qinghai Province and developing plans with local officials and funders to construct a second Birth Centre and to implement all elements of the three-level approach in other areas of Qinghai Province and the Tibetan Plateau.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge funding from the following organizations at UCLA: the Council on Research, the Center for the Study of Women, and the Bixby Center on Population and Reproductive Health, Fielding School of Public Health. We are also grateful for support for this project from the Qinghai Province Science Technology Support Program (Qing hai sheng ke ji zhi cheng ji hua xiang mu ![]() ) through TUTMC’s project number 2014-NS-126, entitled Tibetan and Western Natural Birth Skill and Model Research (Zang xi jie he zi ran fen mian ji shu yan jiu yu shi fan

) through TUTMC’s project number 2014-NS-126, entitled Tibetan and Western Natural Birth Skill and Model Research (Zang xi jie he zi ran fen mian ji shu yan jiu yu shi fan ![]() ) Gipson’s work on the project was partly supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD), US National Institutes of Health, Award Number 1K01HD067677. The authors also thank the Tibetan Healing Fund and its donors in support of the three-level approach intervention programme. We are also very grateful to the respondents and field interviewers who participated in the survey.

) Gipson’s work on the project was partly supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD), US National Institutes of Health, Award Number 1K01HD067677. The authors also thank the Tibetan Healing Fund and its donors in support of the three-level approach intervention programme. We are also very grateful to the respondents and field interviewers who participated in the survey.

References

- R Lozano, H Wang, KJ Foreman. Progress toward Millennium Development Goals 4 and 5 on maternal and child mortality: an updated systematic analysis. Lancet. 378(9797): 2011; 1139–1165. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60518-1.

- MC Hogan, KJ Foreman, M Naghavi. Maternal mortality for 181 countries, 1980–2008: a systematic analysis of progress towards Millennium Development Goal 5. Lancet. 375(9726): 2010; 1609–1623. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60518-1.

- TA Houweling, C Ronsmans, OM Campbell. Huge poor-rich inequalities in maternity care: an international comparative study of maternity and child care in developing countries. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 85(10): 2007; 745–754. 10.2471/BLT.06.038588.

- S Gabrysch, OM Campbell. Still too far to walk: literature review of the determinants of delivery service use. BMC Pregnancy & Childbirth. 9: 2009; 34. 10.1186/1471-2393-9-34.

- AD Rath, I Basnett, M Cole. Improving emergency obstetric care in a context of very high maternal mortality: the Nepal Safer Motherhood Project 1997–2004. Reproductive Health Matters. 15(30): 2007; 72–80. 10.1016/S0968-8080(07)30329-7.

- S Ahmed, AA Creanga, DG Gillespie. Economic status, education and empowerment: implications for maternal health service utilization in developing countries. PLoS One. 5(6): 2010; e11190. 10.1371/journal.pone.0011190.

- M Berer. Maternal mortality or women's health: time for action. Reproductive Health Matters. 20(39): 2012; 5–10. dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0968-8080(12)39632-8.

- S Thomsen, DTP Hoa, M Målqvist. Promoting equity to achieve maternal and child health. Reproductive Health Matters. 19(38): 2011; 176–182. 10.1016/S0968-8080(11)38586-2.

- XL Feng, S Guo, D Hipgrave. China’s facility-based birth strategy and neonatal mortality: a population-based epidemiological study. Lancet. 378(9801): 2011; 1493–1500. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61096-9.

- X Liu, H Yan, D Wang. The evaluation of “Safe Motherhood” program on maternal care utilization in rural western China: a difference in difference approach. BMC Public Health. 10: 2010; 566. 10.1186/1471-2458-10-566.

- XL Feng, L Xu, Y Guo. Socioeconomic inequalities in hospital births in China between 1988 and 2008. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 89(6): 2011; 432–441. 10.2471/BLT.10.085274.

- XL Feng, J Zhu, L Zhang. Socio-economic disparities in maternal mortality in China between 1996 and 2006. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 117(12): 2010; 1527–1536. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02707.x.

- B Subha Sri, N Sarojini, R Khanna. An investigation of maternal deaths following public protests in a tribal district of Madhya Pradesh, central India. Reproductive Health Matters. 20(39): 2012; 11–20. 10.1016/S0968-8080(12)39599-2.

- Y Guo, C Ronsmans, A Lin. Time trends and regional difference in maternal mortality in China from 2000 to 2005. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 87(12): 2009; 913–920. 10.2471/BLT.08.060426.

- X Liu, X Zhou, H Yan. Use of maternal healthcare services in 10 provinces of rural western China. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 114(3): 2011; 260–264. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.04.005.

- Z Wu, P Lei, E Hemminki. Changes and equity in the use of maternal health care in China: from 1991 to 2003. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 16(2): 2012; 501–509. 10.1007/s10995-011-0773-1.

- J Liang, J Zhu, L Dai. Maternal mortality in China, 1996–2005. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 110(2): 2010; 93–96. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.03.013.

- YY Zhou, J Zhu, YP Wang. Trends of maternal mortality ratio during 1996–2010 in China. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 45(10): 2011; 934–939.

- Y Gao, L Barclay, S Kildea. Barriers to increasing hospital birth rates in rural Shanxi Province, China. Reproductive Health Matters. 18(36): 2010; 35–45. 10.1016/S0968-8080(10)36523-2.

- A Harris, Y Zhou, H Liao. Challenges to maternal health care utilization among ethnic minority women in a resource-poor region of Sichuan Province, China. Health Policy and Planning. 25(4): 2010; 311–318. 10.1093/heapol/czp062.

- M Wellhoner, ACC Lee, K Deutsch. Maternal and child health in Yushu, Qinghai Province, China. Inequality Journal for Equity in Health. 10: 2011; 42. 10.1186/1475-9276-10-42.

- Bureau of Statistics of Qinghai Province. Bulletin for Main Statistics of the Sixth Population Census in Qinghai in 2010. No. 1.

- AM Fischer. Population invasion versus urban exclusion in the Tibetan areas of western China. Population and Development Review. 34(4): 2008; 631–662. 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2008.00244.x.

- All China Data Center. Population by County. http://chinadataonline.org/member/county/countytshow.asp.

- All China Data Center. China 2000 Census Data. http://chinadataonline.org/member/county2000/ybListDetail.asp?ID=2727#.

- J Gittelsohn, A Steckler, CC Johnson. Formative research in school and community-based health programs and studies: ‘State of the art’ and the TAAG approach. Health Education & Behavior. 33(1): 2006; 25–39. 10.1177/1090198105282412.

- S Thaddeus, D Maine. Too far to walk: maternal mortality in context. Social Science & Medicine. 38(8): 1994; 1091–1110. 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90226-7.

- Gyaltsen K, Gewa C, Greenlee H, et al. Socioeconomic status and maternal and child health in rural Tibetan villages. http://repositories.cdlib.org/ccpr/olwp/CCPR-Special-07.

- V Adams, S Miller, J Chertow. Having a ‘safe delivery’: conflicting views from Tibet. Health Care for Women International. 26(9): 2005; 821–851. 10.1080/07399330500230920.

- L Klee. Home away from home: the alternative birth center. Social Science & Medicine. 23(1): 1986; 9–16. 10.1016/0277-9536(86)90319-9.

- SR Stapleton, C Osborne, J Illuzzi. Outcomes of care in birth centers: demonstration of a durable model. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health. 58(1): 2013; 3–14. 10.1111/jmwh.12003.

- Gipson J, Gyaltsen K, Hicks AL, et al. Tibetan women’s perspectives and satisfaction with delivery care in a rural birth centre in Western China. Under review 2014.

- Gipson J, Gyaltsen K, Gyal L, et al. Maternal health seeking by rural Tibetan women: characteristics of women delivering at a newly-constructed birth center in western China. Under review 2014.

- JP Souza, MA Parpinelli, E Amaral. Population surveys using validated questionnaires provided useful information on the prevalence of maternal morbidities. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 61(2): 2008; 169–176. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.04.009.

- JP Souza, MHD Sousa, MA Parpinelli. Self-reported maternal morbidity and associated factors among Brazilian women. Revista da Associação Médica Brasileira. 54(3): 2008; 249–255. 10.1590/S0104-42302008000300019.

- Partnership for Maternal, Newborn & Child Health. A global review of the key interventions related to reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health. Geneva: PMNCH; 2011. http://www.who.int/pmnch/knowledge/publications/201112_essential_interventions/en/index.html.