Abstract

This article explores the purpose, function and impact of legal restrictions imposed on children’s and young people’s involvement in sexual activity and their access to sexual and reproductive health services. Whilst there is no consensus on the age at which it is appropriate or acceptable for children and young people to start having sex, the existence of a minimum legal age for sexual consent is almost universal across national jurisdictions, and many states have imposed legal rules that place restrictions on children’s and young people’s independent access to health services, including sexual health services. The article draws on evidence and analysis from a recent study conducted by the International Planned Parenthood Federation in collaboration with the Coram Children’s Legal Centre, UK, which involved a global mapping of laws in relation to sexual and reproductive rights, and exploratory qualitative research in the UK, El Salvador and Senegal amongst young people and health care providers. The article critically examines the social and cultural basis for these rules, arguing that the legal concept of child protection is often founded on gendered ideas about the appropriate boundaries of childhood knowledge and behaviour. It concludes that laws which restrict children’s access to services may function to place children and young people at risk: denying them the ability to access essential information, advice and treatment.

Résumé

Cet article étudie le but, la fonction et l’impact des restrictions légales imposées à la participation d’enfants et de jeunes à l’activité sexuelle et leur accès aux services de santé sexuelle et génésique. S’il n’y a pas de consensus sur l’âge auquel il est approprié ou acceptable que les enfants et les jeunes commencent à être sexuellement actifs, l’existence d’un âge minimum légal du consentement sexuel est presque universel dans les juridictions nationales, et beaucoup d’États ont imposé des règles juridiques qui restreignent l’accès indépendant des enfants et des jeunes aux services de santé, notamment sexuelle. L’article s’inspire de données et d’analyses d’une récente étude réalisée par la Fédération internationale pour la planification familiale en collaboration avec le Coram Children’s Legal Centre, Royaume-Uni, qui a recensé les lois sur les droits sexuels et génésiques, et d’une recherche qualitative exploratoire menée au Royaume-Uni, en El Salvador et au Sénégal auprès de jeunes et de prestataires de soins de santé. L’article examine de manière critique la base sociale et culturelle de ces règles, avançant que le concept juridique de protection de l’enfant est souvent fondé sur des conceptions sexuées des limites convenables imposées aux connaissances et comportements infantiles. Il conclut que les lois qui restreignent l’accès des enfants aux services peuvent créer des risques pour les enfants et les jeunes en leur refusant la possibilité de bénéficier d’informations, de services et de traitements essentiels.

Resumen

Este artículo explora el propósito, función e impacto de las restricciones legales impuestas sobre la participación de niños y personas jóvenes en la actividad sexual y su acceso a servicios de salud sexual y reproductiva. Aunque no existe un consenso en cuanto a la edad a la cual es apropiado o aceptable que los niños y personas jóvenes empiecen a tener relaciones sexuales, la existencia de una edad legal mínima para el consentimiento sexual es casi universal en las jurisdicciones nacionales, y muchos Estados han establecido reglas jurídicas que imponen restricciones sobre el acceso independiente de los niños y las personas jóvenes a los servicios de salud, incluidos los servicios de salud sexual. Este artículo se basa en evidencia y análisis de un estudio reciente realizado por la Federación Internacional de Planificación de la Familia en colaboración con Coram Children’s Legal Centre, en el Reino Unido, que consistió en el mapeo mundial de las leyes relacionadas con los derechos sexuales y reproductivos, e investigaciones exploratorias cualitativas realizadas en el Reino Unido, El Salvador y Senegal entre personas jóvenes y profesionales de la salud. El artículo examina de manera crítica la base social y cultural para estas reglas, argumentando que el concepto jurídico de protección infantil está usualmente fundado en ideas de género respecto a los límites apropiados para los conocimientos y comportamientos en la infancia. Concluye que las leyes que restringen el acceso de los niños a los servicios posiblemente pongan en riesgo a los niños y los jóvenes: negándoles la posibilidad de obtener información, tratamiento y servicios esenciales.

At what age or stage of development is it appropriate for children and young peopleFootnote* to start having sex? The question may be commonplace; but the answer is highly contested, context specific, and shrouded in controversy. Whilst in some contexts sexual expression may be viewed as a normal and even valuable aspect of a young person’s development, in others, it may be restricted, discouraged and even condemned. Often these two narratives exist simultaneously, such that young people must navigate an array of ambivalent and conflicting sexual identities. As one teenager in Northern Ireland recently commented, young people may be “slagged for being virgins” whilst simultaneously encouraged to remain abstinent until marriage.Citation1

“Childhood” as a conceptual category is often constructed as a period of sexual immaturity and innocence. Lack of sexual knowledge and experience is part of what is thought to distinguish children from adults as separate and distinct categories of persons.Citation2 Dr. Stevi Jackson has highlighted the powerful social discourse that “children and sex should be kept apart” and anthropologist Barrie Thorne has explored how specifically “female sexuality…actively associated with children, connotes danger and endangerment”.Citation3,4

In many cultures, and throughout much of history, the institution of marriage has been seen as the fundamental demarcation of both a person’s transition from childhood to adulthood, as well as their transition from virginity to sexual maturity, and this has been especially the case for women and girls,Citation5 reflecting a sense in which sexuality is both gendered and age-bound.Citation6 Significantly, gendered and age-linked constructions of sexuality are not only matters of culture and social norms; they are also a matter of law. Almost all states around the world have established a minimum legal age for sexual consent; that is, a prescribed age below which a child is deemed unable to consent to sexual activity.

The article draws on evidence and analysis from a recent study conducted by the International Planned Parenthood Federation in collaboration with the Coram Children’s Legal Centre, UK, which involved a global mapping of laws in relation to sexual and reproductive rights, and exploratory qualitative research in the UK, El Salvador and Senegal amongst young people and health care providers. It also draws on published literature relating to childhood, youth and sexuality, and its legal regulation. The literature was used to assist in drawing broader theoretical findings from the qualitative empirical and legal research.

Legal regulation of child sexuality: the legal age of sexual consent

The establishment of a minimum legal age for sexual consent is one of the many ways that governments seek to negotiate a fundamental tension which runs through the heart of contemporary discourses concerning the nature of childhood, and the scope and boundaries of children’s rights. On the one hand, children are rights holders, with capacity and autonomy; on the other hand, they are a subordinate group, defined by their dependency and need for protection. In fact, by definition, children do not possess the full citizenship rights associated with legal personhood, which are only bestowed on individuals after they have passed a certain age, the age of legal majority, typically established at 18 years.Citation7 Matthew Waites argues that age of consent laws contribute to defining the concept of citizenship, and constitute an attempt to strike a “difficult balance between the protection rights of children, and the rights to self-determination of adults” [emphasis added].Citation8

Laws prohibiting sex before a certain age, therefore, are typically understood as fulfilling a protective purpose: to preserve the special nature of childhood; to shelter children from sexual exploitation and corruption by adults, and consequent risks of physical and mental harm. This is reflected in the fact that age of consent laws are typically included in a State’s criminal law relating to sexual offences, which establish the crime of sex with a child under a certain age as statutory rape, unlawful carnal knowledge or paedophilia.Citation9

Today, the existence of a minimum legal age for sexual consent is almost universal across national jurisdictions (although not always in the form of a single, discrete number), as well as being a matter of international human rights law.Citation8,10 Whilst international human rights law calls on states to establish a legal age for sexual consent, there is no internationally agreed standard for what the minimum age of sexual consent should be, and legal ages vary widely in different countries, from as young as 12 years in countries such as the Philippines and Mexico, to as old as 21 years in Cameroon.Citation9 In some legal systems, such as variant applications of Sharia law, a person’s chronological age may be considered less important than their stage of physical development.Citation11 Furthermore, in many legal contexts there is no specific age established for consent to sex, per se, but an individual is only legally allowed to give such consent in the context of marriage.Citation9 Significantly, it is very common for states to establish different legal ages of consent for married and unmarried individuals, for boys and for girls, and for particular sexual partnerships and acts.Citation9

Whilst there is very little consensus around what the specific age of sexual consent should be, what appears almost universal is the notion that youth and childhood sexuality is a matter for legal regulation, and that there is at least some threshold below which sexual activity involving a child or young person is considered problematic and thus subject to state prohibition and control.Citation11 Furthermore, the lowest established legal limits indicate consensus around the idea that this minimum age should never, at least, be set below the age of puberty. In fact, when age of consent provisions first started appearing in national legislation, they tended to reflect the onset of biological sexual maturity, with most states establishing the limit at around 12–13 years; this was also typically the time at which a person was legally able to get married.Citation11 Thus, the history of state regulation of sexual activity has long established connections between physical/ biological development, reproduction, marriage, and the legal sanction of sexual agency and decision-making.Citation4

Over time, the age of sexual consent in many states around the world has gradually been rising, rupturing the link between puberty and sexual consent, and extending the period of time between which a child may first be physically capable of reproducing and first legally able to have sex.Citation11 As a result of dramatic changes in diet, nutrition, health and climate, in many contexts around the world, there is (albeit contested) evidence that the average age of onset of puberty is decreasing. At the same time, and more significantly, the age of social adulthood is steadily increasing, as young people are tending to delay marriage, remain within education for longer periods of time and therefore seek work and accumulate income and resources at a later age.Citation6 Therefore, whilst in ‘traditional’ societies the transition from childhood to adulthood tended to be rapid and distinct, in the context of increasing urbanisation, economic development and globalisation, the state of youth, a period of “in-between-ness” during which a person is no longer a child but not yet fully an adult, is emerging as a significant social categoryCitation6; presenting a challenge to established legal and policy institutions which have historically conferred little attention to youth as a distinct division or class.

And yet the prohibition on pre-adult sexual activity, anchored in concerns about the body and ideas about childhood and sexual immaturity are strikingly resilient. Even in contexts where the age of sexual consent is set at the higher end of the spectrum (18–21 years) young people may be taught to abstain from sex because their “sexual organs are not fully grown”.Citation12 Despite the decreasing relevance of the age of physical puberty for defining sexual readiness, and the lack of consensus around the specific age at which sexual activity becomes ‘normal’, ideas about the appropriate boundaries of childhood and youth sexuality remain grounded in notions of biology: underage sex is thought unsafe because it is believed to be unnatural. This reflects a powerful, pervasive discourse that sexuality is innate and universal, despite a body of anthropological literature that has sought to document how the social meaning that is ascribed to different sexual acts has varied widely throughout history and across cultures.Citation4

Understanding the legal concept of protection in relation to children

The idea that childhood sexuality is unnatural is logically associated with the idea that it is (physically and psychologically) harmful. It is the status of children as sexual innocents that makes them vulnerable to corruption.Citation4 Sexual activity involving children is not only thought to be wrong because children are understood to lack capacity to consent to sexual acts, it is perceived as inherently harmful in its own right, because it violates commonplace ideals concerning the appropriate behaviour, expression and knowledge of children.Citation2 These sentiments are also reflected in law, where crimes of sexual violence, especially those involving children, are often depicted in terms of the defilement or corruption of a child.Footnote*

The point here is not to dispute the protective purpose of age of consent laws, but rather to draw attention to the fact that the legal concept of protection is constructed in terms of dominant norms that describe and prescribe identities and appropriate behaviours associated with gender, sexuality and childhood. In fact, in spite of common assumptions to the contrary, legal definitions of sexual violence, including statutory rape, often prioritise preserving age-related and gendered sexual values, over and above concerns about consent. This is evident upon examining how states have typically established variant ages for sexual consent (and marriage) on the grounds of gender, sexual orientation or marital status.

It is significant that in every State where there is an unequal age of sexual consent and of marriage on the basis of sex, the established age is younger for girls.Citation9 If the purpose of these laws were to protect young people from non-consensual sexual activity (i.e. rape), such rules would be incoherent and unjustified as, due to their subordinate social position, girls are especially vulnerable to such violence.Citation13–15 These laws are, rather, grounded in other justifications and assumptions, which have at their core harmful and discriminatory stereotypes about gender.

Firstly, it is often held that girls have a different (i.e. faster) rate of intellectual, physical and sexual development compared to boys, an idea that has strong roots in contemporary biological, neurological and psychological development theories, as well as religious doctrines, and everyday social discourse.Citation8 Sinikka Aapola et al. argue that the idea that girls mature earlier than boys is associated with expectations that girls should be the “responsible” partner in the relationship, which in turn renders girls the principal target for blame and judgement in the case of any social and sexual transgression.Citation4,16

Not entirely consistently, there is also a widespread notion that it is preferable for girls to be less mature than their (male) sexual partners, to reflect the hierarchical nature of the relationship that is supposed to exist between them.Citation6

In addition to discriminating between children on the grounds of sex, legal rules have often established exceptions to the minimum age of sexual consent for children, especially girls, if they are already married, even in cases where these girls have not reached the minimum legal age for marriage. For example, in Brunei, the minimum age of consent for girls is set at 16 years, with an exception for girls who are already married, in which case the age of consent is set at 13 years, while the minimum age for marriage is established at 14 years.Citation17 Similarly, in Thailand, the minimum age of sexual consent is established at 15 years, except for a girl who is married, in which case it is 13 years, despite the fact that the minimum age for marriage is 17 years.Citation18 More concerning still, the laws of some states provide a remedy for rape and statutory rape of a girl on condition that the perpetrator subsequently marries his victim. For example, article 344 of the Penal Code in the Philippines provides that legal marriage is a remedy or defence for a range of sexual offences including seduction, acts of lasciviousness and rape and statutory rape.Citation19 Such laws imply that early sexual activity is only harmful to girls where it takes place outside of the institution of marriage; and that rape and statutory rape of a girl is criminal on the grounds that it violates social norms about the appropriate context for sexual expression, and not because it violates the sexual autonomy and agency of a child.

Finally, in those states where same-sex sexual activity is not entirely forbidden, it is common for states to establish a higher age of consent for sex between men compared to heterosexual sex, which both reflects and reinforces the idea that same-sex relationships between men are relatively more dangerous and should be discouraged.Citation9 Concerning consent to lesbian sex, on the other hand, the law around the world has generally historically been altogether silent, reflecting a widespread failure of dominant institutions to acknowledge the existence of lesbian women and girls.Citation20

Regulating young people’s access to sexual and reproductive health services

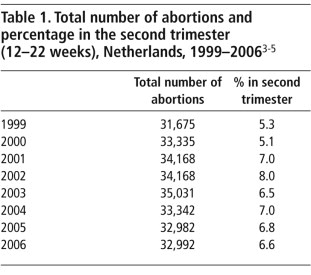

Age of consent laws, therefore, serve as a means for regulating children’s and young people’s sexual activity, (gendered) identity and behaviour. But these laws do not, of course, guarantee that young people will remain abstinent in practice. Data on age at first sex collected by the Guttmacher Institute from 30 countries around the world clearly demonstrates that significant proportions of children and young people have had sexual experiences before the legal age of consent in their countries,Citation21 and recent statistics from the World Health Organization estimate that about 16 million girls aged 15 to 19 and some 1 million girls under 15 give birth every year, most in low- and middle-income countries. Moreover, every year, some three million girls aged 15–19 undergo unsafe abortions.Citation22

This presents a serious policy challenge for the public health sector, particularly in contexts where the age of sexual consent is established at the higher end of the spectrum: that many children and young people who are not legally recognised as able to consent to sex are in fact sexually active, and in need of sexual and reproductive health services. This dilemma has given rise to a hodgepodge of confused legal, policy and programmatic measures which place various age-based limitations on children’s decision-making, in an attempt to negotiate a balance between the legal protection of children, on the one hand, and their access to sexual and reproductive health services on the other.

The development of UK law is particularly illustrative of how these tensions have been negotiated by State judiciaries. In 1982, a case was brought before the UK courts to determine whether the provision of contraceptives to a girl under the age of 16 (the age of sexual consent in the UK) was lawful without the consent of her parents. The case (Gillick v West Norfolk & Wisbech Area Health Authority) reached the House of Lords, where it was decided that medical professionals should have the discretion to determine, on a case-by-case basis, whether a young person under 16 has the competency to independently consent to medical treatment, including contraceptive services.Citation23 As evidence of children’s legal capacity to consent to obtain contraception, Lord Fraser, who gave the leading judgement in the case, noted that: “a minor under the age of 16 can, within certain limits enter into a contract. He or she can also sue and be sued, and can give evidence on oath.”Citation23 Despite the fact that the legal age of sexual consent was 16 years, Lord Fraser felt compelled to cite as precedent a 1966 case in which it was held that: “There are many girls under 16 who know full well what it [sex] is all about and can properly consent” and therefore in order to establish that a girl under 16 had been raped: “the prosecution…must prove either that [the girl] physically resisted, or…that her understanding and knowledge were such that she was not in a position to decide whether to consent or resist.” Lord Fraser concluded that:

“A girl under 16 can give sufficiently effective consent to sexual intercourse to lead to the legal result that the man involved does not commit the crime of rape… Accordingly, I am not disposed to hold now… that a girl aged less than 16 lacks the power to give valid consent to contraceptive advice or treatment, merely on account of her age”.Citation23

Unfortunately, the compromises created in law and policy across the world may be inadequate to guarantee either children or young people’s right to live freely from sexual violence, or their ability to access the health services they need to stay healthy when they do have sex. Legal rules have typically imposed age-based restrictions on children and young people’s independent and confidential access to sexual and reproductive health services, either by requiring parental or other adult consent before they are able to access services, or through establishing a legal obligation on service providers to report cases of sexual activity involving children to child protection authorities or the police, which constitutes a limitation on their right to confidentiality.Citation9

For example, in Lithuania, children under the age of 16 years cannot access contraception without parental consent, and in Poland the minimum age of access without parental consent is 18 years.Citation9 Similarly, the law in Zimbabwe has typically been interpreted as prohibiting access of children under the age of 18 years to sexual and reproductive health services, including HIV testing and treatment without parental consent.Citation24 The law in Northern Ireland (Sexual Offences Act 2008) imposes a mandatory reporting obligation on health service providers, whereby they must refer all cases of sexual activity involving children under 13 years old, and of anyone under the age of 16 years engaging in sexual activity with someone aged 18 years or above, to the police, regardless of the particular circumstance in each case.Citation1

These restrictions are highly problematic; particularly because empirical evidence, included below, indicates that laws which restrict children and young people’s independent and confidential access to sexual and reproductive health services may create significant substantive barriers to their willingness and ability to access any formal service at all.

The impact of age-restrictive law on young people’s access to services: the evidence

Studies conducted cross-culturally have demonstrated that feelings of shame, embarrassment and fear of judgement (particularly by adult authority figures) are some of the most significant factors preventing children and young people’s access to sexual and reproductive health services, and that children and young people consistently rate confidentiality as one of the most important and essential features of a service that they would be willing to access.

For example, a survey of 295 children conducted in the UK found that 86.1% of children would be more willing to access a service if it was confidential, and that whilst 70.8% would like regular check-ups, 54.6% would not be willing to attend a service at all if it were not confidential. An even greater number of children, 63.1%, reported that they would not attend a service if they thought that child protection services might be informed.Citation25

Recent qualitative research commissioned by the International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF) indicates that children and young people may be especially concerned about keeping information confidential from their parents; this is an important finding, given that parental consent requirements are a common way that states legislate for children and young people’s (formal) ability to access sexual and reproductive health services.Citation1 It appears that young people’s privacy concerns stretch to worries about administrative details, such as information from the sexual health service potentially arriving via post.Citation1 Health care providers in Northern Ireland expressed the view that mandatory reporting requirements were not in the best interests of children because involving police and social services may result in negative outcomes for children whose cases are reported, as well as having a negative impact on their access to sexual and reproductive health services more broadly.Citation1

The IPPF-commissioned study included qualitative research in El SalvadorCitation5 and SenegalCitation12 as well as the UKCitation1. Interestingly, though the findings are not necessarily representative, they indicated that even across widely different social, political, economic and religious contexts, young people’s desire for confidentiality and privacy, experiences of shame and consequent unwillingness to access sexual and reproductive health services services, were strikingly similar. Feelings of shame appeared particularly intensive for young women and girls. Young people expressed concern that they would be subject to disrespect and gossip from assumptions being made about their sexual behaviour.Citation1,5 One girl in Northern Ireland equated having to sit in public waiting rooms at sexual health clinics as tantamount to “slut shaming”.Citation1

Other studies exploring young people’s access to sexual and reproductive health services around the world have arrived at the same conclusions. For example, a 2010 study in Nepal found that embarrassment about the possibility of being “caught” at a sexual health clinic, particularly by adult family members, and fear that service providers would not respect confidentiality, was a significant barrier to young people’s access to contraceptives.Citation26 Similarly, a 2012 study in Zimbabwe concluded that embarrassment is more likely to stop young people sharing their health problems than a lack of knowledge or awareness.Citation27

The IPPF studies explored how age-based restrictions on young people’s sexual rights and access to services is both a reflection of socio-cultural norms and a regulatory force which normalises ideas about what is acceptable and unacceptable sexual behaviour.Citation5 The research concluded thatCitation1,5,13 criminal law prohibiting sexual activity involving a child below a given age may function to control young people’s sexual behaviour and criminalise young people who engage in sexual relationships rather than protecting them from sexual violence, (including that perpetrated by adult men, which is often widespread and carried out with impunity).Citation28

In El Salvador, the absolute legal prohibition on abortion is a reflection of ideologies about femininity, marriage, and motherhood, which promotes the social role of mother as strictly the preserve of married women, and the only acceptable goal of female sexuality and personhood. The law criminalising abortion functions to restrict female access to sexual rights not associated with reproduction, and solidifies taboos and stigma associated with sexual agency of young, unmarried women and girls. Thus, legal restrictions on abortion amount to a strategy for promoting abstinence amongst children.Citation12

And yet, particularly given the importance of confidentiality and the power of shame in relation to underage sex, the substantive impact of age-restrictive laws may only be to place children and young people at risk: denying them the ability to access the information, advice and health services that they need to make healthy, autonomous decisions about sex. Carmen Barroso argues that the law criminalising consensual sex between adolescents aged 14–18 years in Peru “left medical providers unclear of the types of care they could offer adolescents, and it made young people reluctant to seek the services they needed, due to fear of punishment”. She concludes that as a result, rates of teen pregnancy and HIV infection among youth in Peru remain stubbornly high.Citation29 Similarly, a 2012 study on age-related barriers to HIV and AIDS services in RwandaCitation30 found that laws in Rwanda regulating sexual activity or protecting adolescents’ rights to reproductive health services do not reflect the average age of sexual debut. The paper argues, therefore, that legal provisions which deny young people under the age of 21 years access to independent and confidential sexual and reproductive health services, including HIV testing, are at least partially responsible for the alarmingly high rates of HIV infection amongst adolescents.Citation30

Concluding thoughts

In spite of the evidence, there remains significant resistance to the idea that age-based restrictions on children’s and young people’s access to sexual and reproductive health services should be reduced, let alone eradicated. Of course, it must be acknowledged that children and young people are in need of (legal) protection. Due to their inferior social status and relative powerlessness, they are undoubtedly vulnerable to risk of harm. As Matthew Waites wisely cautions:

“Arguments in favour of granting young children autonomy in sexual decision-making are… flawed through underestimating structural power relations. They seek to grant children formal recognition of their moral agency without challenging the unequal social contexts in which they are embedded.”Citation8

This analysis constitutes a subtle reframing of the protection vs. autonomy paradigm, at least in the way that it is typically applied to young people’s access to sexual and reproductive health services. Even in jurisdictions such as the UK, where the legal framework is considered (relatively) liberal, and flexibly designed and applied, the question remains as to whether any restriction on children’s and young people’s access to services can avail a rational end. If we are to argue that a restrictive law serves a protective purpose, we must begin by asking ourselves what exactly it is that we mean by ‘protection’.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Jennifer Roest, Coram Children’s Legal Centre, for her invaluable contributions and Prof. Carolyn Hamilton, Coram Children’s Legal Centre, for her helpful supervision. We would also like to thank the International Planned Parenthood Federation for their support. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors.

Notes

* We use the term ‘children and young people’ to refer to persons aged up to 24 years. This is in accordance with the internationally recognised legal definition of ‘children’ as referring to those aged up to 18 years (see e.g. article 1, UN Convention on the Rights of the Child) and the WHO-adopted definition of ‘young people’ as referring to persons aged 15–24 years. Both definitions are widely used in law and policy.

* For example, Article 167, Penal Code, 1997 (El Salvador) and Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Act 2006 (Ireland).

References

- Coram Children’s Legal Centre. Over-protected and under-served: a multi-country study on legal barriers to young people’s access to sexual and reproductive health services – United Kingdom Case Study. 2014; IPPF: London. http://www.childrenslegalcentre.com/index.php?page=international_research_projects.

- MJ Kehily. Introduction to Childhood Studies. 2004; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK.

- Stevi Jackson, quoted in Kehily MJ, editor. Introduction to Childhood Studies. Maidenhead, UK: Open University Press; 2004.

- MJ Kehily, H Montgomery. Innocence and experience, a historical approach to childhood and sexuality. MJ Kehily. Introduction to Childhood Studies. 2004; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK.

- Coram Children’s Legal Centre. Over-protected and under-served: A multi-country study on legal barriers to young people’s access to sexual and reproductive health services – Senegal Case Study. 2014; IPPF: London. http://www.childrenslegalcentre.com/index.php?page=international_research_projects.

- A Eerdewijk. The ABC of unsafe sex: the sexualities of young people in Dakar (Senegal). http://repository.ubn.ru.nl/bitstream/handle/2066/56076/56076.pdf?sequence=1

- R Allen. The nature of responsibility and restorative justice. L Walgrave. Restorative Justice for Juveniles: Potentialities, Risks and Problems. 1998; Leuven University Press: Leuven.

- M Waites. The Age of Consent: Young People, Sexuality and Citizenship. 2005; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK.

- Coram Children’s Legal Centre. Qualitative Research on Legal Barriers to Young People’s Access to Sexual and Reproductive Health Services – Inception Report. 2014; IPPF: London. http://www.childrenslegalcentre.com/index.php?page=international_research_projects.

- UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC). CRC General Comment No. 4: Adolescent Health and Development in the Context of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, 1 July 2003. CRC/GC/2003/4. http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=CRC%2fGC%2f2003%2f4&Lang=en

- H Graupner. Sexual consent: the criminal law in Europe and overseas. Archives of Sexual Behaviour. 29(5): 2000; 415–461. 10.1023/A:1001986103125.

- Coram Children’s Legal Centre. Over-protected and under-served: A multi country study on legal barriers to young people’s access to sexual and reproductive health services – El Salvador Case Study. 2014; IPPF: London. http://www.childrenslegalcentre.com/index.php?page=international_research_projects.

- World Health Organization. Global and regional estimates of violence against women. 2013; WHO: Geneva. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/85239/1/9789241564625_eng.pdf.

- UN Women. Violence against women prevalence data: Surveys by Country. New York; 2012. http://www.endvawnow.org/uploads/browser/files/vawprevalence_matrix_june2013.pdf

- UN-HABITAT. State of the World’s Cities. Nairobi; 2006/2007. p. 144.

- S Aapola, M Gonnik, A Harris. Young Femininity, Girlhood Power and Social Change. 2005; Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Unlawful Carnal Knowledge Act 1984 (Brunei). http://www.lexadin.nl/wlg/legis/nofr/oeur/lxwebri.htm.

- Penal Code Amendment Act 2003 (Thailand). http://www.no-trafficking.org/resources_laws_thailand.html.

- Revised Penal Code 1930 (Philippines). http://www.chanrobles.com/acts/.

- M Waites. Inventing ‘A lesbian age of consent’? the history of the minimum age of consent between women in the UK. Social and Legal Studies. 11(3): 2002; 323–342. 10.1177/096466390201100301.

- Guttmacher Institute. Demystifying Data: A Guide to using Evidence to Improve Young People’s Sexual Health and Rights. New York; 2013. http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/demystifying-data.pdf

- World Health Organization. Adolescent pregnancy. Fact sheet No. 364. Updated September 2014. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs364/en/

- Gillick v West Norfolk and Wisbech Area Health Authority (1985) 3 All ER 402. http://www.hrcr.org/safrica/childrens_rights/Gillick_WestNorfolk.htm.

- UNFPA. Legal and policy issues relating to HIV and young people in selected African countries. Preliminary information - Compiled by the Centre for Human Rights, Faculty of Law, University of Pretoria as part of the African Human Rights Moot Court Competition, 2010. April 2011. http://www.unfpa.org/webdav/site/global/shared/iattyp/docs/Legal%20&%20Policy%20issues%20on%20HIV%20&%20YP%20%20rapid%20survey.pdf

- N Thomas, E Murray, KE Rogstad. Confidentiality is essential if young people are to access sexual health services. International Journal of STD and AIDS. 17(8): 2006; 525–529.

- P Regmi, E Teijlingen, P Simkada. Barriers to sexual health services for young people in Nepal. Journal of Health Population and Nutrition. 28(6): 2010; 629–627. 10.1258/095646206778145686.

- Y Care International. Neglected health issues facing young people in Zimbabwe. November 2013. http://www.ycareinternational.org/publications/neglected-health-issues-facing-young-people-in-zimbabwe/

- M Hume. ‘It's as if you don't know, because you don't do anything about it’: gender and violence in El Salvador. Facing gender-based violence in El Salvador. Environment and Urbanization. 16(2): 2004; 63–72.

- C Barroso. Beyond Cairo: Sexual and reproductive rights of young people in the new development agenda. Global Public Health. 9(6): 2014; 639–646. 10.1080/17441692.2014.917198.

- A Binagwaho, A Fuller, B Kerry. Adolescents and the right to health: Eliminating age-related barriers to HIV/AIDS services in Rwanda. AIDS Care. 24(7): 2012; 936–942. 10.1080/09540121.2011.648159.