Abstract

Background

Ingestion of raw vegetables represented an important mean of transmission of several infectious diseases. No previous surveys have been conducted to evaluate the prevalence of parasitic contamination of vegetables in Egypt. Therefore, this study aimed to detect the parasitic contamination in some common raw vegetables in Alexandria, Egypt.

Methods

It was based on: extraction of parasitic stages from the foodstuffs, concentration of the extract by centrifugation, staining of the different stages by modified Zeihl–Neelsen stain and modified trichrome stain to allow visualization of protozoal oocysts and spores of Microsporidium, and identification by microscopy. Scores of parasite density were evaluated.

Results

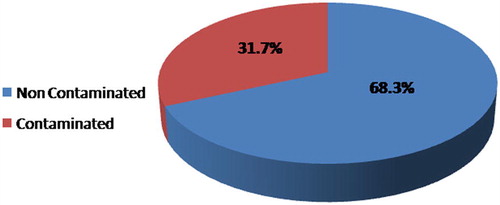

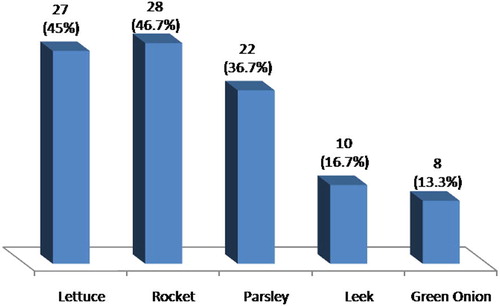

Intestinal parasites were detected in 31.7% of the examined samples. The parasites included Ascaris lumbricoides eggs, Toxocara spp. eggs, Hymenolepis nana eggs, Giardia spp. cysts, Cryptosporidium spp. oocysts, Cyclospora spp. oocysts and Microsporidium spp. spores. The highest number of contaminated samples was detected in rocket (46.7%) while the least number of contaminated samples was detected in green onion (13.3%). Cryptosporidium spp. oocysts were considered the highest prevalent parasite detected in raw vegetables (29.3%) with the highest score density in rocket samples. It was followed by Microsporidium spp. spores (25.3%), Cyclospora spp. oocysts (21.3%), A. lumbricoides eggs (20.3%), Toxocara spp. eggs (19%), Giardia spp. cysts (6.7%) and finally H. nana eggs (2.6%). There was no significant difference between the number of contaminated samples in spring and summer or autumn and winter. However, the number was significantly higher in spring and summer in comparison to winter and autumn (p < 0.001).

Conclusion

These findings may have important implications for global food safety and emphasize the importance of raw vegetables in threatening public health by transmission of intestinal parasites to humans in Alexandria, Egypt.

1 Introduction

Vegetables are essential part of a healthy human diet owing to their nutritional value. Raw vegetables are great source of vitamins, dietary fiber and minerals; and their regular consumption is associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular diseases, stroke and certain cancers.Citation1 Some vegetables are eaten raw as salad to retain the natural taste and preserve heat labile nutrients. Ingestion of raw vegetables represented an important mean of transmission of several infectious diseases because of their complex surface and porosity, which unfortunately facilitate pathogen attachment and survival.Citation2 The consumption of raw vegetables without proper washing is an important route in the transmission of parasitic diseases.Citation3 There has been an increase in the number of reported cases of food-borne illness linked to fresh vegetables. Several factors may contribute to contamination of crops. They become contaminated while still on the plant in fields, Orchards, or during harvesting, transport, processing, distribution and marketing or even at home.Citation4 Wastewater was increasingly used for irrigation in the 1970s and early 1980s. In many developing countries, use of insufficiently treated wastewater to irrigate vegetables has been reported to be responsible for the high rates of contamination with pathogenic parasites.Citation4 Contamination of soil with animal wastes and increased application of improperly composted manures to soil in which vegetables are grown also play a role in parasite contamination to green vegetables.Citation5 Bad hygienic practice during production, transport, processing and preparation by handlers including consumers also contribute in vegetable contaminations.Citation6 Other factors which affect the susceptibility of the public to foodborne diseases, also play a role in increasing the number of infected cases. Highly susceptible persons because of ageing, malnutrition, HIV infection and other underlying medical conditions are markedly increased. Changes in lifestyle, food consumption patterns, such as the increase in the number of people eating meals prepared in restaurants, canteens and fast food outlets as well as from street food vendors who do not always respect food safety increase the risk of exposure to foodborne infections.Citation7

In the past, the risk of human infection with parasites was considered to be limited to distinct geographic regions because of parasites’ adaptations to specific definitive hosts, selective intermediate hosts and particular environmental conditions. These barriers are slowly being breached—first by international travel developing into a major industry, and second, by rapid, refrigerated food transport which became available to an unprecedented degree at the end of the 20th century. Taking into account that a proportion of the vegetables cultivated in these developing countries are exported to developed ones, the risk of spreading these contaminations to other countries cannot be overlooked.Citation8

In developing countries, because of inadequate or even non-existing systems for routine diagnosis and monitoring or reporting for many of the food-borne pathogens, most outbreaks caused by contaminated vegetables go undetected and the incidence of their occurrence in food is underestimated.Citation9 Practical and reliable detection methods for monitoring foodstuffs will aid the prevention of parasitic disease outbreaks associated with contaminated food.Citation10 Referring to existing scientific literatures, no previous surveys have been conducted to evaluate the presence of parasitic contamination in vegetables in Egypt. Therefore, this study aimed to detect the parasitic contamination in some common green vegetables used for raw consumption in Alexandria, Egypt.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Sample collection

Five types of green vegetables were selected in this study {lettuce (Lactuca sativa), rocket (Eruca sativa), parsley (Petroselinum hortense), leek (Allium porrum) and green onion (Allium ascalonicum)}. A total of 300 samples (60 samples from each type of green vegetables) were purchased at the smallest retail size available. Samples were collected monthly (five sample for each type of green vegetables) and were picked randomly from commercial groceries, supermarkets, street vendors, and food stall markets in Alexandria, Egypt during May 2010–April 2011. Two hundred grams were being prepared from the edible part of each vegetable sample separately according to the household practice to obtain qualitative and quantitative estimation of parasitic contamination.

2.2 Procedure for sample preparation and washing

The vegetable samples were transported to laboratory in plastic bags. According to the traditional procedure which is generally used for washing vegetables, they were immersed immediately in tap water inside a sink and left approximately 6–7 min for sedimentation of mud and dust. Then, it was gently collected and was put in a plastic basket. Each vegetable sample was eluted by vigorous agitation followed by sonication (INC. ultrasonic processor W-380, Japan) of each specimen for 30 min in 1 L of sterile phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4), to which 50 ml of 0.01% Tween 80 was added. The eluent was filtered through gauze and then dispensed into clean centrifuge tubes and centrifuged at 2000×g for 30 min. The supernatant was discarded into disinfectant jar, and the pellet was washed of Tween 80 by centrifugation (2000×g for 30 min) with sterile phosphate-buffered saline in the standard procedure described by Gaspard and Schwartzbrod.Citation11

2.3 Detection of parasites

The sediment was mixed and examined as follow:

| (1) | Simple smear: a drop of the sediment was applied on the center of a clean grease-free slide. A clean cover slip was placed gently to avoid air bubbles and over flooding. The preparation was examined under a light microscope using ×10 and ×40 objectives.Citation12 | ||||

| (2) | Iodine smear: a drop of the sediment was mixed with a drop of Lugol's Iodine solution and examined as in simple smear.Citation12 | ||||

| (3) | Simple and iodine smears were used for detection of parasitic eggs, cysts and larva. The process was systematically repeated until the mixture in each test tube was exhausted. Eggs, cysts and oocysts of parasites found under the light microscope were identified as previously described by Downes and Ito.Citation13 | ||||

| (4) | Staining of sediment smear was performed by Modified Zeihl–NeelsenCitation14 and modified trichromeCitation15 to detect protozoal parasitic (oo)cysts and spores of Microsporidium spp. | ||||

Each parasite's eggs, cysts or oocysts present in each sample were enumerated and densities of each species were expressed as “many” (>three (oo) cysts per high-power field; >20 eggs per low-power field); “moderate” (two (oo)cysts per high-power field; 10–19 eggs per-low power field); “few” (one (oo)cyst per high-power field; three to nine eggs per low-power field); and “rare” (two to five cysts and <two eggs per 100μ of sediment). For simplification, numerical values were assigned to each density: many, 4; moderate, 3; few, 2; rare, 1; and none, 0.Citation16

2.4 The statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out using chi-square tests of the SPSS software version 9.0 for windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) to compare the rate of contamination of vegetables among different seasons. The differences were considered significant at p < 0.05.

3 Results

Results are summarized in and and and .

Table 1 The number and percentage of contaminated samples and the mean of parasite score density in some raw green vegetables.

Table 2 The number and percentage of contaminated samples with intestinal parasites in different seasons in some raw green vegetables.

Intestinal parasites were detected in 31.7% of the examined samples (). The parasites detected in raw green vegetable samples were Cryptosporidium spp. oocysts, Microsporidium spp. spores, Cyclospora spp. oocysts, Giardia spp. cysts Ascaris lumbricoides eggs, Toxocara spp. eggs, and Hymenolepis nana eggs. The highest number of contaminated samples was detected in rocket (46.7%) while the least number of contaminated samples was detected in green onion (13.3%) ( and ).

Rocket was the most contaminated green vegetable in this study (46.7%). Cryptosporidium spp. were the most prevalent parasite in rocket samples (45%). Microsporidium spp. spores contamination followed that of Cryptosporidium spp. oocysts (36.7%). This was followed by Ascaris eggs (35%), Cyclospora spp. oocysts (31.7%), Toxocara eggs (25%), Giardia spp. cysts (10%) and finally H. nana eggs (3.3%) ( and ).

As regards lettuce samples, 45% were contaminated with parasites. The most prevalent parasite detected in lettuce was Cryptosporidium spp. oocysts (43.3%) followed by Microsporidium spp. spores (41.7%). The number of contaminated lettuce samples with Ascaris eggs and Cyclospora spp. oocysts was equal (38.3%). This was followed by Toxocara eggs (31.7%), Giardia spp. cysts (15%) and finally H. nana eggs (6.7%) ( and ).

Contamination of parsley samples was detected in 36.7% of the total samples. They were mainly contaminated with Cryptosporidium spp. oocysts (33.3%). This was followed by Cyclospora spp. oocysts (25%), and Toxocara eggs (20%). The number of contaminated parsley samples with Microsporidium spp. spores and Ascaris eggs is equal (16.7%). The least number of contaminated samples was detected in samples contaminated with Giardia spp. cysts and H. nana eggs (5% and 3.3% respectively) ( and ).

Regarding leek contaminated samples (16.7%), they were mainly contaminated with Cryptosporidium spp. oocysts (14.3%). Cyclospora spp. oocysts, and Toxocara eggs contaminated samples were equal (8.3%). Ascaris eggs and Giardia spp. cysts were detected in 6.7% and 1.7% of parsley samples respectively. H. nana eggs were not detected in any of parsley sample (0%). ( and ).

Green onion samples were the least contaminated samples in this study. Contamination was detected in only 13.3% of the examined samples. The highest contamination was by Microsporidia spp. (18.3%) followed by Cryptosporidium spp. oocysts (11.7%), Toxocara eggs in 10%, Ascaris eggs in 5% and finally Cyclospora spp. oocysts in 3.3%. H. nana eggs and Giardia spp. cysts were not detected in any of green onion samples (0%) ( and ).

Cryptosporidium spp. oocysts were considered the highest prevalent parasite detected in raw vegetables (29.3%). It was followed by Microsporidium spp. spores in 25.3%, Cyclospora spp. oocysts in 21.3%, A. lumbricoides eggs in 20.3%, Toxocara spp. Eggs in 19%, Giardia spp. cysts in 6.7% and finally H. nana eggs in 2.6% ().

The mean of parasite score density in the contaminated samples ranged between (2.22) and (0). The highest score of parasite density was that of Cryptosporidium spp. oocysts (2.22). It was detected in contaminated rocket samples. However, the least score of parasite density was that of H. nana eggs (0) in parsley, leek and green onion samples. The least score was also detected in green onion samples with Giardia spp. cysts (0) (). The highest rate of parasitic contamination in vegetable samples in different seasons was found in spring (49.3%), followed by summer (48%). There was no significant difference between the number of contaminated samples in these two seasons. Lesser contamination rates were found in autumn (20%) and in winter (9.3%). There was also no significant difference between these two seasons. Comparing the rate of parasitic contamination in the four seasons, it was found that the number of contaminated samples in spring was significantly higher than the number of contaminated samples in winter and autumn. Also the number of contaminated samples in summer was significantly higher when compared to the number of contaminated samples in winter and autumn (x2 = 42.069; p < 0.001). The highest rate of contamination in spring was found in lettuce samples (73.3%) while the lowest contamination in the same season was in leek (20%). In winter, the number of contaminated samples was equal in rocket, parsley and leek (13.3%). One sample only was contaminated in lettuce (6.6%) however no parasite was detected in green onion samples during this season (0%) ().

4 Discussion

Different parasitic stages can contaminate several foodstuffs. If the food-borne route is suspected in an outbreak, it is easy to identify how the food implicated became contaminated. However, it is often difficult to associate an outbreak with a particular food item.Citation3 Vegetables, and especially salads, are an important route of transmission of intestinal parasites and have been shown to be an important source of food borne outbreaks in developing countries.Citation17 The most likely hypothesis of contamination is that it occurred before harvest, either by contaminated manure, manure compost, sewage sludge, irrigation water, runoff water from livestock operations or directly from wild and domestic animals. These potential contamination events are all plausible and consistent with the assumption that the level of contamination must have been high.Citation18

Alexandria is a large coastal city. It is considered the second capital of Egypt after Cairo. It is mainly an industrial city, with some agriculture fields.Citation19 Therefore, the present study aimed at investigating some green vegetables that are frequently eaten raw for their possible contamination with parasites in Alexandria. This study showed a considerably high level of contamination of green vegetables foodstuff with intestinal parasites in Alexandria (31.7%). These results were in agreement with another one in Ghana which evaluated the overall parasitic contamination of the vegetables as 36%.Citation20 Parasitic contamination of the vegetables in another study in Nigeria was also 36%.Citation21 Recently, Ettehad et al.Citation22 reported, slightly lower level of contamination of consumed native garden vegetables with intestinal parasites (29%) in Ardabil city, Iran. Higher rate of contamination of green vegetables was detected in wholesale and retail markets in Tripoli, Libya in the study carried out by Abougraina in 2009. This study detected 58% positive samples for intestinal parasites.Citation23 Examination of vegetable samples in Kenya by Nyarango in 2008 revealed also higher rate of contamination (75.9%).Citation16

In the present work, five types of common consumed raw vegetables in Alexandria were examined; rocket, lettuce, parsley, leek and green onion. The highest rate of contamination was detected in rocket samples (46.7%). It was followed by lettuce samples (45%). This could be due to the fact that the degree of contamination varies according to the shape and surface of vegetables. Green leafy vegetables as lettuce, rocket and parsley have uneven surfaces and makes parasitic eggs, cysts and oocysts attached to the surface of the vegetable more easily, either in the farm or when washed with contaminated water. On the other hand, vegetables with smooth surface as leek and green onion had the least prevalence because its smooth surface reduces the rate of parasitic attachment.Citation21

These results were in agreement with that of a study done in Tripoli, Libya. It detected parasitic contamination in 96% of lettuce and 100% of cress samples. Lettuce and cress samples were contaminated significantly more often than those of tomato samples in the same study.Citation23 Damen et al.,Citation21 detected contamination in 40% of lettuce samples, and 24% in green leafy vegetable in Nigeria. In contrast, other study in Saudi Arabia in 2006 revealed that the highest number of contaminated samples was found in green onions (28%) and the lowest contamination was in leek (13%). The prevalence of parasites in other vegetables in the same study was 17% in each of lettuce and water cress.Citation24 Another two studies in Iran reported that the highest contamination was in leek (51.8% and 66.7%).Citation25,Citation26 Several factors may contribute to such differences. These may include, geographical location, type and number of samples examined, methods used for detection of the intestinal parasites, type of water used for irrigation, and post-harvesting handling methods of such vegetables which are different from country to another.

In the present work, Cryptosporidium was the most prevalent parasite contaminating green vegetable samples (29.3%). A recent paper by researchers in USA demonstrated that Cryptosporidium oocysts were capable of strongly adhering to spinach plants after contact with contaminated water and were also internalized within the leaves.Citation27 Although contamination of vegetables may occur in a variety of ways, it is mainly associated with the water used for irrigation. The use of sewage contaminated water for irrigation of vegetables is a common practice in developing countries including Egypt. The main water sources used for irrigation of fields in Alexandria are river water from El Mahmoudeya canal, untreated wastewater and rarely rain water.Citation28 A study done in Alexandria on detection of Cryptosporidium oocysts in irrigation water from El Mahmoudeya canal detected a high rate of contamination of irrigation water with this parasite (100%).Citation29 Specifically, Cryptosporidium was linked to the consumption of vegetables in Nordic countries.Citation30,Citation31 In addition, Cryptosporidium was found in 4% samples from fresh produce in the study carried out by Robertson and Gjerde in Norway in 2001.Citation32 These also agree with another study in Costa Rica which reports the occurrence of some pathogenic micro-organisms in vegetables consumed on a daily basis. In this study, Cryptosporidium spp. oocysts were found in 2.5% of lettuce samples. In addition, it was reported in 5.2% of cilantro leaves and in 8.7% of cilantro roots. A 1.2% incidence was found in other vegetable samples (carrot, cucumber, radish and tomatoes). Oocysts of this parasite were absent, in the same study, in cabbage.Citation33 On the other hand, out of 19 salad products in a field study in Valencia, Spain, Cryptosporidium oocysts were detected in 12 samples (63.2%).Citation34

Microsporidian spores are the second prevalent parasites in green vegetables in this study (25.3%). The highest contamination was detected in lettuce samples (41.7%). This may be due to the strong adhesion to, or internalization in leafy vegetables, thereby successfully evading the effects of washing and disinfection.Citation35 Microsporidian spores resist standard wastewater treatment and can be found in sewage sludge end products commonly used for fertilization of ready-to-eat crops or in runoff-impacted surface water used for irrigation.Citation36 Microsporidian spores have also been identified in irrigation water used for ready-to-eat crop production.Citation37 Reports on contamination of green vegetables with Microsporidian spores are scanty. Unspecified spore species have been found in samples from strawberries, lettuce, and parsley in the study carried out by Calvo in 2004.Citation33 A study was done in Sweden suggesting that cucumber slices in both cheese sandwiches and a salad were the most probable vehicle of transmission of Microsporidian spores causing an outbreak.Citation35 Several studies also detected spores in ground,Citation38 surface waterCitation38,Citation39 and crop-irrigation water,Citation37 and in fresh produce such as raspberries, beans and lettuce.Citation40

Cyclospora oocysts in the present study were detected in 21.3% of the examined samples. Lettuce samples were also the main type contaminated with Cyclospora oocysts (38.3%). This parasite has also been isolated from lettuce in Peru (1.8%).Citation41 It was also isolated from lettuce heads in Egypt.Citation42 Green leafy vegetables in another study in Nepal were contaminated with Cyclospora oocysts.Citation43 These reports also agree with a study in Germany in which the only foods associated with Cyclospora risk of infection were two salad side dishes prepared from lettuce imported from southern Europe and spiced with fresh green leafy herbs.Citation44 Large-scale outbreaks of Cyclospora spp. infection associated with raspberries imported from Guatemala, basil, and mesclun lettuce have been also reported.Citation44–Citation46

In the present study, Ascaris eggs were detected in 20.3% of the examined samples. The highest contamination was detected in lettuce samples (38.3%). In a study done in India, Ascaris eggs were the most predominant parasite observed. It was detected in 36% of the examined samples, mainly in lettuce.Citation47 The rates of contamination with Ascaris eggs in vegetables in Iran were much lower than these values. It was 2.5% in JiruftCitation48 and 2.3% in Qazvin.Citation26 The rate of contamination in Saudi Arabia was also lower than that detected in this study. It was 16% in leafy vegetables examined.Citation24 A study in Tripoli, Libya reported a higher rate of contamination (68%) of fresh salad vegetables with Ascaris eggs. They were detected in tomato (19%), cucumber (75%), lettuce (96%) and cress (96%), respectively.Citation23 In Ghana, Amoah, (2006) identified Ascaris eggs in 60% of the vegetables obtained from urban markets. This could be attributed to its high level of persistence and resistance. The presence of Ascaris eggs in vegetables can be due to the quality of water used for irrigation and the probable use of untreated night soil.Citation20 In Sanliurfa, Turkey, soil-transmitted helminthes (mainly Ascaris eggs) were detected in 14% of fresh vegetables and in 84% of soil samples where vegetables were cultivated in 61% of irrigation water.Citation49 Two previous studies in Alexandria detected Ascaris eggs in 1.9% and 0.16% of soil samples collected from different areas.Citation50,Citation51 Biologically, the highest health risk is for helminth infections compared with other pathogens because helminthes persist for longer periods in the environment and the infective dose is small.Citation52

In the present work, Toxocara eggs were detected in19% of the examined samples. Lettuce samples were the main vegetable contaminated with this parasite (31.7%). In Tripoli, Libya, Toxocara eggs were detected in 11%, 14%, 48% and 41% of the tomato, cucumber, lettuce, and cress samples respectively.Citation23 Kozan et al. in Turkey in 2007,Citation53 detected Toxocara spp. in 1.5% of unwashed raw vegetables used for salad. Toxocara spp. were detected in another study carried out in Turkey by Avcioglu in 2011 in four (2.0%) and two (1.0%) unwashed vegetables, respectively, mostly among leafy vegetables such as lettuce and parsley.Citation54

The prevalence of Giardia spp. cysts detected in this study was 6.7%. The highest contamination was detected in lettuce (in 15% of the examined samples). The finding of this study is similar to previous reports in Iran. It was 8.2% in Shahrekord,Citation55 14% in Jiruft,Citation48 6.5% in Tehran,Citation56 9% in ArdabilCitation22 and 4% in Qazvin.Citation57 In Saudi Arabia, in the study carried out by Al-Megrin 2010, 31.6% of leafy vegetables were contaminated with Giardia spp. cysts.Citation58 Robertson and GjerdeCitation32 reported a contamination rate of 2.1% with Giardia spp. in fruits and vegetables in Norway. Giardia intestinalis was only detected in 5.2% of cilantro leaves and in 2.5% of cilantro roots in Costa Rica.Citation33 Erdogru and SenerCitation59 found Giardia cysts in only 5.5% of lettuce samples. Contrary to these findings, another study in Libya detected Giardia cysts in 10% of the total vegetable samples examined with cucumber samples being most contaminated (19%), followed by cress (11%), lettuce (4%) and tomato (3%) samples.Citation23

H. nana eggs were the least parasite contaminating green vegetables in this study. They were detected in 2.6% of the examined samples. Lettuce was the main type of vegetable contaminated with this parasite (6.7%). They were not detected in leek or green onion samples. H. nana eggs were detected in a previous study in Libya, in 2.4% of the total examined samples. In this study, cabbage had the highest parasitic contamination (64%) and tomatoes recorded the least parasitic contamination (20%).Citation23 In another study in Turkey, H. nana eggs were detected in 6.25% of examined samples.Citation53 In Qazvin, Iran, H. nana eggs were detected in 0.5% only of tested samples and it was the least parasite contaminating the green vegetables. Leek was the highest contaminated vegetable with this parasite in the same study (66.7%).Citation57

The presence of helminth eggs in different vegetables is mainly related to contamination of soil rather than contamination of irrigating water.Citation49 In a previous study on soil transmitted parasites in Alexandria, Toxocara eggs and H. nana eggs were detected in 16.7% in El-Ameria. H. nana eggs were also detected in Sharek district while, Toxocara eggs were also detected in Sharek, El-Montazah, Waset, Gharb, El-Gomrok and Borg El-Arab.Citation50

Considering seasonal variability, this study indicated that the rate of parasitic contamination in vegetable samples was the highest in spring (49.3%) and the lowest in winter (9.3%). However there was no significant difference between spring and summer and between autumn and winter. On the other hand, statistical analysis revealed that the rate of contamination was significantly higher (p < 0.001) in spring and summer than in autumn and winter. Our finding is consistent with previous studies that reported higher rate of parasitic contamination in vegetables during warm seasons than those during cold seasons.Citation42,Citation53 It has been determined that the excretion of parasite's eggs to environment by human or animals is high in warm seasons comparing to cold seasons.Citation60 Also, the frequent use of untreated wastewater for irrigation of vegetable fields in Alexandria during spring and summer could be a reason for higher rate of parasitic contamination in these seasons. Another reason might be the difference in weather as oocysts thrive in tropical countries. They are even found to increase in summer season.Citation29

5 Conclusion

These findings may have important implications for global food safety and emphasize the importance of raw vegetables in threatening public health by transmission of intestinal parasites to humans in Alexandria.

The local health and environmental authorities should improve the sanitary conditions in the areas where the vegetables are cultivated and consumed. Proper treatment of wastewater used for irrigation of vegetables should be implemented. There is also dire need for the improvement of sanitary facilities in our markets and vegetable vendors. Media programs should inform the consumers the potential health consequences of the intestinal parasites through consumption of raw vegetables, and the importance of proper washing and disinfecting of vegetables before consumption. In addition, they should focus on the necessity of good sanitation hygiene and risks of acquiring intestinal parasites. More researches are needed to do surveys of parasitic contamination in green vegetables in Alexandria including different districts. Also, other surveys must be done in different governorates in Egypt. In these researches, viability of the contaminating parasites or larvation and sporulation of the detected parasites can be done. Also, other researches must be done to evaluate the level of contamination of irrigation water and soil in which green vegetables are cultivated. Different ways of disinfection of raw green vegetables must be improved.

Notes

Peer review under responsibility of Alexandria University Faculty of Medicine.

Available online 25 September 2012

References

- M.A.Van DuynE.PivonkaOverview of the health benefits of fruit and vegetable consumption for the dietetics professional: selected literatureJ Am Diet Assoc10012200015111521

- K.E.KnielD.S.LindsayS.S.SumnerC.R.HackneyM.D.PiersonJ.P.DubeyExamination of attachment and survival of Toxoplasma gondii oocysts on raspberries and blueberriesJ Parasitol882002790793

- T.R.SlifkoH.V.SmithJ.B.RoseEmerging parasite zoonoses associated with water and foodInt J Parasitol3012–13200013791393

- A.H.MahviE.B.KiaHelminth eggs in raw and treated wastewater in the Islamic Republic of IranEast Mediterr Health J121–22006137143

- L.R.BeuchatEcological factors influencing survival and growth of human pathogens on raw fruits and vegetablesMicrobes Infect442002413423

- S.GuptaS.SatpatiS.NayekD.GaraiEffect of wastewater irrigation on vegetables in relation to bioaccumulation of heavy metals and biochemical changesEnviron Monit Assess1651–42010169177

- WHO, World Health Organization, Food borne Diseases, Emerging, (2002) <http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs124/en/print.html>.

- P.A.OrlandiD.M.T.ChuJ.W.BierG.J.JacksonParasites and the food supplyFood Technol5620027281

- P.DornyN.PraetN.DeckersS.GabrielEmerging food-borne parasitesVet Parasitol16332009196206

- L.A.JaykusEpidemiology and detection as options for control of viral and parasitic foodborne diseaseEmerg Infect Dis31997529539

- P.G.GaspardJ.SchwartzbrodParasite contamination (helminth eggs) in sludge treatment plants: definition of a sampling strategyInt J Hyg Environ Health20622003117122

- L.S.GarciaMacroscopic and microscopic examination of fecal specimensL.S.GarciaDiagnostic medical parasitology5th ed.2007American Society of Microbiology (ASM)Washington, DC782830

- F.P.DownesK.ItoCompendium of methods for the microbiological examination of foods4th ed.2001American Public Health AssociationWashington, DC

- M.A.BrondsonRapid dimethyl modified acid fast stain of Cryptosporidium oocyst in stool specimensJ Clin Microbiol191984952955

- E.KokoskinT.W.GyorkosA.CamasL.CandiottiT.PurtillB.WardModified technique for efficient detection of MicrosporidiaJ Clin Microbiol32199410741075

- R.M.NyarangoP.A.AlooE.W.KabiruB.O.NyanchongThe risk of pathogenic intestinal parasite infections in Kisii Municipality, KenyaBMC Public Health1482008237

- S.M.PiresA.R.VieiraE.PerezFo.LoD.WongT.HaldAttributing human foodborne illness to food sources and water in Latin America and the Caribbean using data from outbreak investigationsInt J Food Microbiol15232012129138

- Taban B.MercanogluA.K.HalkmanDo leafy green vegetables and their ready-to-eat [RTE] salads carry a risk of foodborne pathogens?Anaerobe1762011286287

- Alexandria- Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexandria>.

- P.AmoahP.DrechselR.C.AbaidooW.J.NtowPesticide and pathogen contamination of vegetables in Ghana's urban marketsArch Environ Con Tox501200616

- J.G.DamenE.B.BanwatD.Z.EgahJ.A.AllananaParasitic contamination of vegetables in JosNigeria Ann Afr Med62007115118

- G.H.EttehadM.SharifL.GhorbaniH.ZiaeiPrevalence of intestinal parasites in vegetables consumed in ArdabilIran Food Control192008790794

- A.K.AbougrainaM.H.NahaisiN.S.MadiaM.M.SaiedK.S.GhengheshcParasitological contamination in salad vegetables in Tripoli – LibyaIran Food Control212010760762

- A.M.Al-BinaliC.S.BelloK.El-ShewyS.E.AbdullaThe prevalence of parasites in commonly used leafy vegetables in South Western, Saudi ArabiaSaudi Med J272006613616

- A.A.FallahK.Pirali-KheirabadiS.FatemehS.Saei-DehkordiPrevalence of parasitic contamination in vegetables used for raw consumption in Shahrekord, Iran: Influence of season and washing procedureIran Food Control2522012617620

- M.ShahnaziM.Jafari-SabetPrevalence of parasitic contamination of raw vegetables in villages of Qazvin ProvinceIran Foodborne Pathog Dis79201010251030

- D.MacarisinG.BauchanR.FayerSpinacia oleracea L. Leaf stomata harboring Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts: a potential threat to food safetyAppl Environ Microbiol762010555559

- Stakeholders Analysis Report, City of Alexandria, Egypt By: Center for Environment and Development in the Arab Region and Europe (CEDARE) October 2007. <http://switch.cedare.int/files28%5CFile2830.pdf>.

- Nabil RA. Detection of Cryptosporidium spp. in different water samples in Alexandria using Real time PCR. MD thesis, Faculty of Medicine, Alexandria University, Egypt, 2012. Unpublished results.

- S.EthelbergM.LisbyL.S.VestergaardH.L.EnemarkK.E.OlsenC.R.StensvoldA foodborne outbreak of Cryptosporidium hominis infectionEpidemiol Infect13732009348356

- Insulander M, de Jong B, Svenungsson B. A food-borne outbreak of cryptosporidiosis among guests and staff at a hotel restaurant in Stockholm county, Sweden, September 2008. Euro Surveill, 2008; 13(51): pii=19071.

- L.J.RobertsonB.GjerdeOccurrence of parasites on fruits and vegetables in NorwayJ Food Prot6411200117931798

- M.M.CalvoM.L.CarazoC.AriasR.ChavesMongeM.ChinchillaPrevalence of Cyclospora spp, Cryptosporidium spp., Microsporidia and fecal coliform determination in fresh fruit and vegetables consumed in Costa RicaArch Latinoam Nutr542004428432

- I.AmorósJ.L.AlonsoG.CuestaCryptosporidium oocysts and Giardia cysts on salad products irrigated with contaminated waterJ Food Prot73201011381140

- V.DecraeneM.S.Lebbad Botero-KleivenA.M.GustavssoM.LöfdahlFirst reported foodborne outbreak associated with Microsporidia Sweden October 2009Epidemiol Infect14032012519527

- T.K.GraczykF.E.LucyL.TamangA.MiraflorHuman enteropathogen load in activated sewage sludge and corresponding sewage sludge end productsAppl Environ Microbiol73200720132015

- J.A.Thurston-EnriquezP.WattS.E.DowdR.EnriquezI.L.PepperC.P.GerbaDetection of protozoan parasites and Microsporidia in irrigation waters used for crop productionJ Food Prot652002378382

- S.E.DowdC.P.GerbaI.L.PepperConfirmation of the human-pathogenic Microsporidia Enterocytozoon bieneusi, Encephalitozoon intestinalis, and Vittaforma corneae in waterAppl Environ Microbiol64199833323335

- S.FournierO.LiguoryM.Santillana-HayatE.GuillotC.SarfatiN.DumoutierDetection of Microsporidia in surface water: a one-year follow-up studyFEMS Immunol Med Microbiol29200095100

- S.JedrzejewskiT.K.GraczykA.Slodkowicz-KowalskaL.TamangA.C.MajewskaQuantitative assessment of contamination of fresh food produce of various retail types by human-virulent Microsporidian sporesAppl Environ Microb7312200740714073

- Y.R.OrtegaC.R.RoxasR.H.GilmanN.J.MillerL.CabreraC.TaquiriIsolation of Cryptosporidium parvum and Cyclospora cayetanensis from vegetables collected in markets of an endemic region in PeruAm J Trop Med Hyg571997683686

- I.Abou el NagaStudies on a newly emerging protozoal pathogen: Cyclospora cayetanensisJ. Egypt Soc Parasitol291999575586

- J.B.SherchandJ.H.CrossM.JimbaS.SherchandM.P.ShresthaStudy of Cyclospora cayetanensis in health care facilities, sewage water and green leafy vegetables in NepalSoutheast Asian J Trop Med Public Health3019995863

- P.C.DöllerKarlDietrichN.FilippS.BrockmannC.DreweckR.VontheinCyclosporiasis outbreak in Germany associated with the consumption of saladEmerg Infect Dis892002992994

- A.Y.HoA.S.LopezM.G.EberhartR.LevensonB.S.FinkelA.J.SilvaOutbreak of cyclosporiasis associated with imported raspberries, Philadelphia, PennsylvaniaEmerg Infect Dis882000783788

- A.S.LopezD.R.DodsonM.J.ArrowoodP.A.OrlandiA.J.da SilvaJ.W.BierOutbreak of cyclosporiasis associated with basil in Missouri in 1999Clin Infect Dis32200110101017

- N.GuptaD.K.KhanS.C.SantraPrevalence of intestinal helminth eggs on vegetables grown in wastewater–irrigated areas of Titagarh, West BengalIndia Food Control202009942945

- A.ZohourP.MolazadehPrevalence of pathogenic parasites in consumed vegetables in JiruftJ Birj Univ Med Sci820011013

- M.UlukanligilA.SeyrekG.AslanH.OzbilgeS.AtayEnvironmental pollution with soil-transmitted helminthes in SanliurfaTurkey Mem I Oswal Cruz962001903909

- Mogahed NF. A study of medically important soil transmitted parasites in Alexandria, thesis, MS. Faculty of Medicine, University of Alexandria, Egypt, 2010.

- N.A.KishkS.R.AllamPrevalence of intestinal helminthes eggs among preschool children and its relation to soil contamination in AlexandriaJ Med Res Inst2112000181192

- P.GaspardJ.WiartJ.SchwartzbrodParasitological contamination of urban sludge used for agricultural purposesWast Manage Res151997429436

- E.KozanF.K.SevimliM.KöseM.EserH.CiçekExamination of helminth contaminated wastewaters used for agricultural purposes in AfyonkarahisarTurkiye Parazitol Derg3132007197200

- H.AvcioğluE.SoykanU.TarakciControl of helminth contamination of raw vegetables by washingVector Borne Zoonotic Dis1122011189191

- Taherian F. Prevalence of Giardia lamblia in healthy people in Shahrekord, Institute of Public Health, Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences Fact Sheet FA-93.2009.

- M.J.GharaviM.R.JahaniM.B.RokniParasitic contamination of vegetables from farms and markets in TehranIran J Pub Health3120028386

- M.ShahnaziM.SharifiZ.KalantariM.A.HeidariN.AgamirkarimiThe study of consumed vegetable parasitic infections in QazvinJQUMS124200983

- A.I.Al-MegrinPrevalence of intestinal parasites in leafy vegetables in RiyadhSaudi Arabia Int J Trop Med520102023

- Ö.ErdoğruH.ŞenerThe contamination of various fruit and vegetable with Enterobius vermicularis, Ascaris eggs, Entamoeba histolyca cysts and Giardia cystsIran Food Control162005559562

- A.EslamiS.RahbariS.Ranjbar-BahadoriA.KamalStudy on the Prevalence Seasonal incidence and economic importance of Parasitic infections of small ruminants in the province of SemnanPajouhesh Sazandegi5820035558