Abstract

Background

Approximately 80% of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) are untreatable because of advanced tumor stages at presentation. Therefore, finding newer markers for screening and diagnosing HCC is of utmost importance. Clusterin (CLU) is a 449 amino acid, heterodimeric glycoprotein with a plausible role in the regeneration, migration, and anti-apoptosis of tumor cells. It has been implicated in many malignancies such as prostate and pancreatic adenocarcinomas, but its role in HCC is not well defined.

Objective

We aimed to evaluate the diagnostic performance of serum CLU level in diagnosing HCC on top of hepatitis C virus-related liver cirrhosis, and comparing it to that of alpha fetoprotein (AFP).

Methods

Twenty cases of apparently healthy subjects, 27 cases of hepatitis C virus-related liver cirrhosis (CHC cases), and 44 HCC cases on top of hepatitis C virus-related liver cirrhosis were included in this study. Serum CLU concentration was determined using a quantitative sandwich enzyme immunoassay technique.

Results

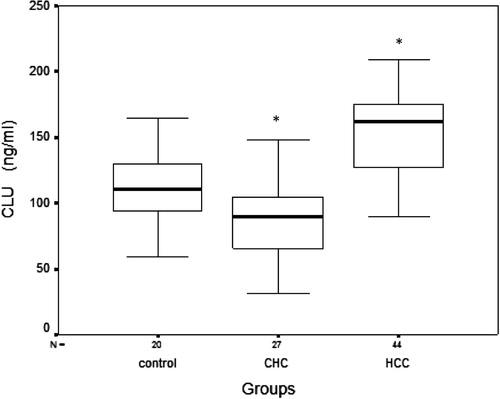

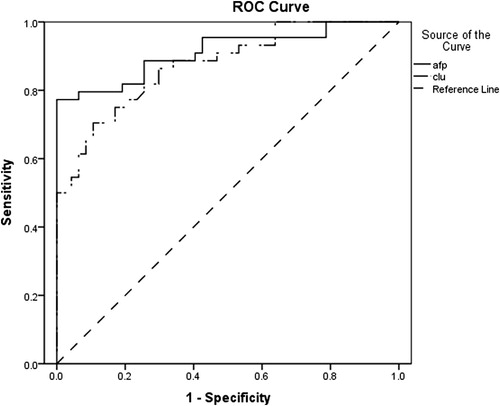

Serum clusterin level showed a significant increase in the HCC group compared to the control group (151.96 ± 32.74 vs. 111.40 ± 27.46) and to the CHC group (151.96 ± 32.74 vs. 89.12 ± 31.62), while a significant decrease in serum clusterin level was found in the CHC group compared to the control group (89.12 ± 31.62 vs. 111.40 ± 27.46). Based on receiver operator characteristic curve analysis, serum AFP still surpassed serum CLU in diagnostic sensitivity (77.3% vs. 70.5%), specificity (100% vs. 90%), and positive and negative predictive values (100% vs. 86.1% and 83.3% vs. 77.6% respectively). The use of a combined parallel approach improved the diagnostic sensitivity (95.5%) and negative predictive value (95.7%) over the single use of AFP.

Conclusions

Although the diagnostic performance of serum AFP outperformed that of serum CLU, their combined parallel approach improved the sensitivity which is required in screening high risk populations such as CHC patients.

1 Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most common cancer worldwide and the most common form of primary liver cancer.Citation1 In Egypt, the overall frequency of HCC is 2.3% among other types of cancer. Over a decade, there was nearly a twofold increase in the proportion of HCC among chronic liver disease patients in Egypt, where 48% of HCC cases were attributed to hepatitis C virus (HCV) related liver cirrhosis. In fact, it has now become widely accepted that HCC nearly exclusively arises in chronic HCV after cirrhosis is established.Citation2

HCC is typically diagnosed late in its course. Indeed, patients who present with cancer symptoms and/or with vascular invasion or extra-hepatic spread have only 50% survival rate at one year. Therapeutic options are determined both by tumor extent and the severity of the underlying liver disease. Although the cornerstone of therapy is surgical resection, the majority of patients are not eligible because of tumor extent or underlying liver dysfunction.

The diagnosis of HCC can be radiological and/or laboratory. Radiological diagnosis depends largely on ultrasonography, triphasic computerized tomography (triphasic CT-scan) and dynamic magnetic resonance imaging (dynamic MRI). The sensitivity of US for the detection of HCC is directly related to tumor size. Another major drawback of US is that it is very much operator- dependent.Citation4,Citation5 Laboratory diagnosis of HCC is established either by measurement of circulating biomarkers or by fine-needle cytology which is invasive with intra- or inter-observer variability.Citation6

The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) guidelines recommended that serum levels of AFP ⩾200 ng/ml may be used instead of fine-needle cytology for diagnosis, especially in patients with liver cirrhosis.Citation3 Nevertheless, the diagnostic performance of AFP is moderate with a sensitivity of 39–65% and specificity of 76–94%, leaving about one-third of cases with early-stage HCC and small tumors (<3 cm) undiagnosed. Meanwhile, increased serum AFP concentration in several other types of cancer, chronic hepatitis, and liver cirrhosis should be taken into consideration. Newer markers are needed to overcome these problems and allow the diagnosis of HCC at an earlier stage.Citation1,Citation6

Clusterin (CLU) is a 449-amino acid, heterodimeric glycoprotein that is ubiquitously expressed and present in most body fluids. Functionally, CLU exerts a chaperone-like activity with action like small heat shock proteins, by binding to misfolded stressed proteins. In contrast to other heat shock proteins, it is present in the extracellular space, where its expression is altered in various diseases.Citation7–Citation8Citation9

So far, CLU is thought to play diverse functions both cytoprotective and cytotoxic, thus resulting in conflicting results.Citation9 For example, its involvement in numerous physiological processes important for carcinogenesis has been reported, including apoptotic cell death, cell adhesion, tissue remodeling, cell cycle regulation, DNA repair, lipid transportation, membrane recycling and immune system regulation.Citation10 Cytoplasmic CLU immunostaining was noted to correlate with poor prognosis in patients with renal cell carcinoma,Citation11 hepatocellular carcinoma,Citation12 urothelial bladder carcinoma,Citation13 and prostate adenocarcinoma.Citation14 Also increased expression of secreted CLU was associated with radioresistance, chemoresistance, and hormone resistance, making CLU a promising target for antitumor therapeutics.Citation15 Both preclinical and clinical phase studies demonstrated that inhibition of CLU expression using antisense oligonucleotides enhances the apoptosis induced by several chemotherapeutic treatments.Citation10 On the other hand, cytoplasmic CLU staining correlated with good prognosis in pancreatic adenocarcinoma and did not correlate with prognosis in breast carcinoma.Citation16,Citation17

As the data are still sporadic and only few studies have investigated CLU in serum, the aim of the present study was to determine serum CLU concentration in CHC and HCC, as well as assess the use of clusterin measurement vs. AFP in the diagnosis of HCC.

2 Materials and methods

A total of 127 adults at the Medical Research Institute Teaching Hospital, Alexandria University, Egypt between August 2010 and April 2012 were candidates for this study, but only 91 cases fulfilled our inclusion and exclusion criteria. All subjects (or their legal guardians) gave their informed consent to the study, which was approved by the local ethics committee of the institute in accordance with The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) for experiments involving humans. These subjects were set into three groups based on clinical and laboratory characteristics:

| - | Group 1(G1): Healthy subjects. This group included 20 apparently healthy blood donors with no history of liver disease. | ||||

| - | Group 2 (G2): 27 patients with chronic hepatitis-C virus infection-related cirrhosis (CHC). | ||||

| - | Group 3 (G3): 44 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma on top of chronic HCV infection-related cirrhosis (HCC group). | ||||

All subjects completed a medical history to retrieve information about health status, current medications, alcohol consumption, and history of viral or toxic hepatitis; had a physical examination and the Child-Pugh scoring system was used for staging the severity of liver disease. Conventional ultrasound and spiral CT-scans of the abdomen were performed in all cases.

Following an overnight eight-hour-fast, eight milliliters of whole venous blood samples were withdrawn from each subject; whole EDTA blood was used for complete blood picture, citrated plasma for prothrombin time determination, serum for routine clinical chemistry and AFP assays and finally the serum was stored in aliquots at −20 °C for the determination of CLU.

For all studied groups screening for serum schistosomal IgG antibodies was done using the indirect haemagglutination test. Serological testing for anti-HCV and hepatitis B virus surface antigen (HBs-Ag) was performed by sandwich enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) technique according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Murex Diagnostic Limited. Dartfold, England). HCV viral load was determined by means of the second generation branched DNA assay (Quantiplex HCV RNA 2.0; Bayer Diagnostics, Emeryville, California, USA). Serum AFP concentration was determined using a two site chemiluminometric immunoassay (ACS–180, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Germany) by the Immulite 1000 Automated Analyzer (Diagnostic Products Corporation). Serum CLU concentration was determined using the ELISA technique according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Biovendor-Laboratorni Medicina a.s., Cat. No. RD194034200R). The assay had a lowest detection limit of 0.5 ng/mL. The remaining biochemical parameters were measured using routine methods by fully automated chemistry analyzer Olympus AU400. The upper limit of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) activity was set at 38 IU/L, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) at 40 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase at 120 IU/L, and gamma glutamyl transferase at 55 and 38 IU/L for males and females respectively. Results of analyses were validated using internal and external quality control provided by Biorad USA.

Hepatitis C related cirrhosis patients (CHC) are those who had (1) positive serum anti-HCV antibodies; (2) cirrhosis compatible with HCV origin proved on ultrasound and spiral CT-scans; and (3) absence of HCC defined by the absence of a focal liver mass on ultrasonography or CT scan.

The diagnosis of HCC was based on the criteria published by the Egyptian Society of Liver Cancer (ESLC) in 2011. These included the presence of a hepatic focal lesion in high risk patients (cirrhotic patients) plus either serum AFP ⩾200 ng/ml, or a triphasic CT-scan showing typical criteria for HCC. If in the presence of a focal lesion ⩾1 cm the AFP level was <200 ng/ml or triphasic CT-scan of the abdomen showed a typical criteria for HCC, then either a dynamic contrast MRI or targeted liver biopsy was performed.Citation18

“Early stage HCC” were identified according to the Milan criteria; those who either have one nodule <5 cm, or three nodules each <3 cm in diameter.Citation19 Meanwhile, vascular invasion, regional lymph node involvement, peritoneal deposits and/or distant metastases were designated as “extrahepatic spread of HCC”.

Patients were excluded if they had (a) hepatitis B virus (HBV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), or schistosomal co-infection, (b) personal history of diabetes or fasting serum glucose ⩾7.0 mmol/L, or a 2-h postprandial serum glucose ⩾11.1 mmol/L, (c) history of ischemic heart disease during the previous 6 months, uncontrolled hypertension, unstable angina, or severe cardiac arrhythmia,Citation20 (d) alcohol consumption >30 g/day (e) inadequate kidney function (creatinine level ⩾150 μmol/L), and (f) received concomitant antitumor treatment.Citation21

2.1 Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done using SPSS version 18 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Normality test was done by the Shapiro-Wilk W test. Descriptive measures were done for each variable in every group. Data comparison between groups was done using the Mann–Whitney test. Spearman correlation coefficient (r) was applied to our results. A p-value less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

For choosing the best cut off value, receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve was generated and the Youden’s index [Youden Index = (sensitivity + specificity) −1] was calculated.Citation22The best cut off values had the highest Youden indices. Diagnostic performance of each marker alone (diagnostic specificity, diagnostic sensitivity, positive and negative predictive values) was compared to the surrogate use of both markers (combined parallel approach) in HCC cases.

3 Results

The studied subjects comprised 91 individuals (20 apparently healthy volunteers: mean age 52.7 ± 3.9 years; 10 (50%) males and 10 (50%) females, 27 CHC cases: mean age 52.53 ± 4.27 years; 18 (66.7%) males and 9 (33.3%) females, and finally HCC cases: mean age 52.18 ± 4.09 years; 25 (56.8%) males and 19 (43.2%) females). According to Child-Pugh (CP) classes, CHC patients in the present study included 8 cases (29.6%) CP class A, 10 cases (37%) CP class B, and 9 cases (33.3%) CP class C. While HCC patients included 13 cases (29.5%) CP class A, 14 cases (31.8%) CP class B, and 17 cases (38.6%) CP class C. Based on the Milan criteria, the studied HCC cases can be sorted into early and late stage HCC; 9 cases (9.9%) and 35 cases (38.5%) respectively. Also the HCC group included 10 cases (11%) with extrahepatic spread and 34 cases (37.5%) without extrahepatic spread.

All subjects in the control group had normal liver biochemistry. As expected, serum AFP (ng/ml) was significantly higher in the HCC cases compared to both the control group (7243 ± 11613.6 vs. 2.79 ± 1.26) (p < 0.001), as well as to CHC patients (7243 ± 11613.6 vs. 19.7 ± 17.92) (p < 0.001), and still significantly higher in the CHC patients compared to the control group (19.7 ± 17.92 vs. 2.79 ± 1.26) (p < 0.001) (). Serum CLU (ng/ml) level showed a significant increase in the HCC group compared to the control group (151.96 ± 32.74 vs. 111.40 ± 27.46) (p < 0.001) and to the CHC group (151.96 ± 32.74 vs. 89.12 ± 31.62) (p < 0.001), while a significant decrease in serum CLU level was found in the CHC group compared to the control group (89.12 ± 31.62 vs. 111.40 ± 27.46) (p = 0.019) () ().

Table 1 Comparison between the studied groups according to serum levels of alpha fetoprotein (AFP) and clusterin (CLU).

There was no significant statistical difference in serum CLU among the different Child-Pugh classes in either the CHC or HCC groups (). Also no significant correlation was found between serum CLU and Child-Pugh score (r = 0.09, p = 0.458).

Table 2 Comparison of serum clusterin (ng/ml) in chronic hepatitis-C virus infection-related cirrhosis (CHC) and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) groups according to Child-Pugh classes.

Moreover, when sorting HCC patients into those with extrahepatic spread of HCC and those without, there was no significant increase in the level of both AFP (p = 0.710) and CLU (p = 0.88). But when HCC patients were categorized according to the Milan criteria, there was a significant increase in serum CLU in early stage HCC when compared to late stage (172.84 ± 24.63 vs. 146.59 ± 32.67) (p = 0.035), but such an increase was not present in serum AFP (p = 0.062) ().

Table 3 Comparison of serum alpha fetoprotein (AFP) and clusterin (CLU) in the hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) group according to different variables.

When using the ROC curve for evaluating the diagnostic performance of serum CLU in relation to serum AFP in diagnosing HCC, the area under the curve of AFP (0.912, p < 0.001) was slightly bigger than that of CLU (0.874, p < 0.001) ().

Youden’s index was calculated to get the best cut off value (COV). The optimal COV for serum CLU was 135 ng/ml and this offered a diagnostic sensitivity of 70.5%, and a diagnostic specificity of 90%. On the other hand, at a COV of 137 ng/ml, serum AFP gave a diagnostic sensitivity of 77.3%, and a diagnostic specificity of 100%. The combined parallel approach improved the diagnostic sensitivity to 95.5% and negative predictive value to 95.7% over the single use of serum AFP in HCC cases, but decreased the specificity to reach 88% and positive predictive value to 87.5% ().

Table 4 Predictive performance of serum alpha fetoprotein (AFP) and clusterin (CLU) as biomarkers for the detection of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

4 Discussion

Hepatocellular carcinoma is a highly malignant and lethal tumor, with an estimated 5-year survival rate of 5–9% from the time of clinical diagnosis.Citation1 It is considered a health burden in Egypt due to its rising incidence.Citation2 However, with the currently available diagnostic tools, HCC is frequently not diagnosed until it has reached an advanced stage when the remaining therapeutic modalities are less effective, leaving this disease with unfavorable prognosis.Citation6 Therefore, finding new markers for screening and diagnosing HCC at an early stage is highly recommended.

Clusterin (CLU) is a highly conserved glycoprotein with a wide tissue distribution. Many physiological processes have been attributed to CLU such as cell adhesion, tissue remodeling, and immune system regulation.Citation10

In the present study, serum CLU was measured by the ELISA technique in a cohort of Egyptian patients (healthy controls, HCV related liver cirrhosis, and HCC cases on top of HCV related liver cirrhosis). We found a significant decrease in serum CLU level in the HCV related cirrhosis patients when compared to the control group. Also, CLU level was higher in Child class A patients compared to Child class C patients, as summarized in . The difference, however, was statistically non-significant. This may point to a possible protective role of CLU against liver cell fibrogenesis which ultimately ends in cirrhosis. Such an assumption was similarly postulated in renal fibrosis by Jung et al, who suggested that up regulation of clusterin during renal injury, in a mouse model, has a protective response against the development of renal fibrosis.Citation23 Likewise, Hogasen et al. and Wang et al. reported a decrease in serum CLU in alcoholic liver cirrhosis and hepatitis B viral liver cirrhosis, respectively.Citation24,Citation25

Clusterin was suggested to be either a pro-apoptotic or a pro-survival factor, rendering it an attractive biomarker for cancer studies as a diagnostic or prognostic or even surprisingly a therapeutic tool.Citation26,Citation27 We found higher serum CLU in the HCC group than both control and HCV related liver cirrhosis, denoting its role in carcinogenesis. Such an increase was similarly reported in HCC in serum level as well as tissue level by previous studies. The former was done by Nafee et al.Citation28 who reported the significant rise of serum CLU in viral related HCC patients, and the latter was done by Kang et al with the use of a tissue microarray method which revealed CLU overexpression immunohistochemically in surgically resected HCCs.Citation12 Furthermore, the increase of CLU level was demonstrated in other tumors; such as bladder cancer,Citation29 colorectal adenocarcinomas,Citation30 and prostate cancer.Citation31 Our finding leads to hypothesize that CLU secretion occurs from tumor cells in HCC and is reflected in its serum level. This is further supported by the fact that clusterin exists as both an intracellular truncated form and an extracellular heterodimeric secreted glycoprotein, making clusterin the only known chaperone protein to be secreted.Citation32

A handful of studies tackled the issue of the diagnostic performance of biomarkers in HCC. In the present study, serum AFP with a cutoff level of 137 ng/ml outperformed serum CLU with a cutoff level of 135 ng/ml in diagnostic sensitivity (77.3% vs. 70.5%), specificity (100% vs. 90%), and positive and negative predictive values (100% vs. 86.1% and 83.3% vs. 77.6%, respectively). Moreover, the use of a combined parallel approach improved the diagnostic sensitivity (95.5%) and negative predictive value (95.7%) over the single use of AFP but decreased the specificity to reach 88% and positive predictive value to be 87.5%, thus improving the sensitivity at the expense of the specificity. On the contrary, Wang et al.,Citation25 demonstrated that serum CLU with a cutoff level of 50 ug/ml outperformed serum AFP with a cutoff level of 15 ng/ml in diagnostic sensitivity (91% vs. 67%), specificity (83% vs. 76%), positive and negative predictive values (93% vs. 88% and 77% vs. 47% respectively). It is worth mentioning that such a low cutoff level of AFP (15 ng/ml) is somehow not applicable in countries with a high prevalence of hepatic diseases especially HCV as in our country. The sensitivity and specificity of the diagnostic biomarker are strongly dependent on the cutoff value above which it is considered positive, and such a cutoff value is affected by the criteria of the studied sample (demographic, clinical, biochemical and statistical) as well as implicated methodological assays, thus explaining the wide variation in diagnostic performance of biomarkers in different studies due to different sample criteria.

The relation of CLU to HCC progression was also variable in different reports. In vitro study using HCC cell lines by Lau et al.Citation33 demonstrated that overexpression of CLU increased cell migration and formation of metastatic tumor nodules, but Wang et al.Citation25 and Nafaa et al.Citation28 found no significant difference of CLU serum levels between different tumor sizes. In our study we did not find a significant increase in serum CLU in HCCs with extrahepatic spread when compared to HCC without extrahepatic spread. Interestingly, our study revealed a significant increase in serum CLU level in early stage HCC when compared to late stage HCC, such an increase was not found in serum AFP. Although this subgroup of early stage HCC comprised only 9 cases, this can be attributed to rarity of such patients due to delayed diagnosis of HCC. We cannot deny the possibility of a random effect due to the small size of this subgroup rendering it difficult for establishing reliable statistical results that could be applied in clinical use. Therefore, we recommend investigating CLU level on a larger cohort to ascertain such an association. But a possible explanation may be that the CLU increase in late stages is directed to the nuclear form rather than the secreted form. Moreover, the complex nature of CLU and its multiple isoforms not only in tissuesCitation34 but also in serum should be considered. Pucci et al.Citation35 explained the diversity of CLU function in colorectal carcinoma by a shift in the pattern of its isoform production. Also Rodríguez-Piñeiro et al.Citation34 pointed to the importance of measuring CLU isoforms over that of total serum level, when they demonstrated the increase of some isoforms and the decrease or absence of others in colorectal carcinoma.

Finally, we can conclude that serum AFP did better than serum CLU in all aspects of diagnostic performance for diagnosing HCC, but still the combined parallel approach improved the sensitivity which is required in screening high risk populations such as CHC patients. But still, further research of larger study populations and with various liver functions status, will be required to examine whether serum CLU is associated with specific liver disease etiologies.

Conflict of interest

We have no conflict of interest to declare.

Notes

Peer review under responsibility of Alexandria University Faculty of Medicine.

Available online 20 June 2014

References

- A.M.LiuT.G.YaoW.WangCirculating miR-15b and miR-130b in serum as potential markers for detecting hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective cohort studyBMJ Open22012e000825

- A.R.El-ZayadiH.M.BadranE.M.BarakatHepatocellular carcinoma in Egypt: a single centre study over a decadeWorld J Gastroenterol1133200551935198

- J.BruixM.ShermanAASLD practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinomaHepatology42200512081236

- I.I.I.DoddW.J.MillerR.L.BaronDetection of malignant tumors in end-stage cirrhotic livers: efficacy of sonography as a screening techniqueAm J Roentgenol1591992727733

- A.S.BefelerA.M.Di BisceglieHepatocellular carcinoma: diagnosis and treatmentGastroenterology122200216091619

- E.N.DebruyneD.VanderschaegheH.V.VlierbergheDiagnostic value of the hemopexin N-glycan profile in hepatocellular carcinoma patientsClin Chem562010823831

- R.M.MorettiM.M.MarelliS.MaiClusterin isoforms differentially affect growth and motility of prostate cells: possible implications in prostate tumorigenesisCancer Res67200710325

- A.AigelsreiterE.JanigJ.SostaricClusterin expression in cholestasis, hepatocellular carcinoma and liver fibrosisHistopathology542009561570

- S.MateriaM.A.CaterL.W.J.KlompClusterin (apolipoprotein J), a molecular chaperone that facilitates degradation of the copper-ATPases ATP7A and ATP7BJBC28620111007310083

- C.L.AndersenT.SchepelerK.ThorsenClusterin expression in normal mucosa and colorectal cancerMol Cell Proteomics6200710391048

- T.KurahashiM.MuramakiK.YamanakaExpression of the secreted form of clusterin protein in renal cell carcinoma as a predictor of disease extensionBJU Int962005895899

- Y.K.KangS.W.HongH.LeeOverexpression of clusterin in human hepatocellular carcinomaHum Pathol35200413401346

- S.KrugerA.MahnkenI.KauschValue of clusterin immunoreactivity as a predictive factor in muscle-invasive urothelial bladder carcinomaUrology672006105109

- H.MiyakeK.YamanakaM.MuramakiEnhanced expression of the secreted form of clusterin following neoadjuvant hormonal therapy as a prognostic predictor in patients undergoing radical prostatectomy for prostate cancerOncol Rep14200513711375

- A.SoS.SinnemannD.HuntsmanKnockdown of the cytoprotective chaperone, clusterin, chemosensitizes human breast cancer cells both in vitro and in vivoMol Cancer Ther420051837

- M.J.XieY.MotooS.B.SuExpression of clusterin in human pancreatic cancerPancreas252002234238

- M.RedondoE.VillarJ.Torres-MunozOverexpression of clusterin in human breast carcinomaAm J Pathol1572000393399

- Egyptian Society of Liver Cancer. The Egyptian guidelines for management of hepatocellular carcinoma [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2012 Oct 31]. Available from: <http://www.egslc.com/content/Guidlines.pdf>.

- V.MazzaferroS.BhooriC.SpositoMilan criteria in liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: an evidence-based analysis of 15 years of experienceLiver Transpl1720114457

- I.P.TrougakosM.PoulakouM.StathatosSerum levels of the senescence biomarker clusterin/apolipoprotein J increase significantly in diabetes type II and during development of coronary heart disease or at myocardial infarctionExp Gerontol37200211751187

- M.E.RosenbergM.S.PallerDifferential gene expression in the recovery from ischemic renal injuryKidney Int39199111561161

- W.J.YoudenIndex for rating diagnostic testsCancer319503235

- G.S.JungM.K.KimY.A.JungClusterin attenuates the development of renal fibrosisJASN2320127385

- K.HogasenC.HomannT.E.MollnesSerum clusterin and vitronectin in alcoholic cirrhosisLiver161996140146

- Y.WangY.H.LiuS.J.MaiEvaluation of serum clusterin as a surveillance tool for human hepatocellular carcinoma with hepatitis B virus related cirrhosisJ Gastroenterol Hepatol25201011231128

- A.E.CaccamoS.DesenzaniL.BelloniNuclear clusterin accumulation during heat shock response: implications for cell survival and thermo-tolerance induction in immortalized and prostate cancer cellsJ Cell Physiol2072006208219

- B.ShannanM.SeifertK.LeskovChallenge and promise: roles for clusterin in pathogenesis, progression and therapy of cancerCell Death Differ1320061219

- A.M.NafeeH.F.PashaS.M.El AalClinical significance of serum clusterin as a biomarker for evaluating diagnosis and metastasis potential of viral-related hepatocellular carcinomaClin Biochem45201210701074

- D.StejskalR.R.FialaEvaluation of serum and urine clusterin as a potential tumor marker for urinary bladder cancerNeoplasma532006343346

- D.KevansJ.FoleyM.TenniswoodHigh clusterin expression correlates with a poor outcome in stage II colorectal cancersCancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev182009393399

- H.MiyakeM.MuramakiJ.FurukawaSerum level of clusterin and its density in men with prostate cancer as novel biomarkers reflecting disease extensionUrology752010454459

- K.N.ChiL.L.SiuH.HirteA phase I study of OGX-011, a 2-methoxyethyl phosphorothioate antisense to clusterin, in combination with docetaxel in patients with advanced cancerClin Cancer Res142008833839

- S.H.LauJ.S.ShamD.XieClusterin plays an important role in hepatocellular carcinoma metastasisOncogene25200612421250

- A.M.Rodríguez-PiñeiroM.P.la CadenaA.López-SacoDifferential expression of serum clusterin isoforms in colorectal cancerMol Cell Proteomics5200616471657

- S.PucciE.BonannoF.PichiorriModulation of different clusterin isoforms in human colon tumorigenesisOncogene2313200422982304