Abstract

Background

Occult HBV infection (OBI) can be defined by the presence of HBV-DNA in the serum of patients who are negative for HBsAg. The presence of OBI has been associated with a poor therapeutic response to alpha IFN in many, but not in all studies.

Objective

The aim of our study was to assess the prevalence of OBI in the serum of Egyptian patients with CHC, and to evaluate its impact on the response to treatment with a combination of Peg-IFNα and RBV.

Materials and methods

Fifty chronic HCV infected patients who were treated with Peg-IFNα once a week in combination with RBV for 48 weeks were included in this study. Patients were divided into two groups, group I which included 25 patients who achieved SVR and group II that included 25 patients who failed to achieve SVR (Non-SVR). Both patient groups were subjected to detailed questionnaire, clinical examination, routine laboratory investigations and virological studies.

Results

No statistical significant difference was found in sex distribution regarding SVR and Non-SVR. The frequency of patients with low viral load has a statistically significant association with SVR patients compared to Non-SVR patients. The frequency of anti-HBc seropositivity has a statistically significant association with the Non-SVR patients compared to SVR patients. Out of 11 anti-HBc positive samples, 10 (90.9%) were positive for the pol and s genes while 9 (81.81%) were positive for the c gene. About 17 (34%) out of 50 patients included in the study were HBV-DNA positive. The frequency of HBV-DNA positive HCV patients has a statistically significant association with Non-SVR patients compared to the SVR patients (p < 0.05).

Conclusion

The prevalence of OBI was higher in our CHCV patients. OBI was significantly associated with poor response to combined Peg-IFNα and RBV therapy.

Abbreviations:

- HBV

- hepatitis B virus

- HCV

- hepatitis C virus

- EDHS

- Egyptian Demographic and Health Survey

- Anti-HCV

- antibody to hepatitis C virus

- Anti-HBc

- anti-hepatitis B core

- HBsAg

- hepatitis B surface antigen

- PCR

- polymerase chain reaction

- OBI

- occult HBV infection

- CHC

- chronic hepatitis C

- Peg-IFN α and RBV

- pegylated interferon alpha and ribavirin

- SVR

- sustained virological response

- RNA

- ribonucleic acid

1 Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections represent the main causes of chronic liver disease worldwide, affecting 350–400 million and 170 million people, respectively.Citation1 HCV is currently the most significant public health problem in Egypt.Citation2 The recently published Egyptian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) in 2008 estimated an overall antibody to hepatitis C virus (anti-HCV) prevalence of 14.7% with an estimated 9.8% of resident Egyptian populations that are chronically infected.Citation3 Anti-hepatitis B core (anti-HBc) sero-positivity in the general population in Egypt is reported to be 10–13%.Citation4

HBV and HCV share common modes of transmission, thus, simultaneous infection is quite frequent, particularly where both viruses are endemic as among people with a high risk for parenteral infections.Citation5 Diagnosis of HBV infection is usually based on the detection of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), and the disappearance of this antigen indicates the clearance of HBV.Citation6 The extensive application of sensitive molecular tests such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and real-time PCR has enabled HBV-DNA to be detected in specimens from individuals without serological evidence of chronic HBV infection.Citation7,Citation8 Occult HBV infection (OBI) can be defined by the presence of HBV-DNA in the serum of patients who are negative for HBsAg.Citation5,Citation9 In the last decade, OBI pattern has been documented and frequently identified in patients with chronic hepatitis C (CHC) infection.Citation8 Its prevalence, which varies according to HBV endemicity, ranges from 30% of CHC patients in Italy to 80% in Japan.Citation2

The currently recommended therapy for CHC is the combination of pegylated interferon alpha and ribavirin (Peg-IFNα and RBV) that proved to be superior to standard IFNα and RBV. Several virological responses may occur, labeled according to their timing relative to treatment. The most important type of virological responses is the sustained virological response (SVR), defined as the absence of HCV-ribonucleic acid (RNA) from serum by a sensitive PCR assay 24 weeks following discontinuation of therapy. More than 50% of patients can achieve an SVR after 24 weeks (in genotypes 2 and 3) or after 48 weeks (in genotypes 1 and 4) of this combination therapy, making HCV a potentially curable disease.Citation10 The presence of OBI has been associated with a poor therapeutic response to alpha IFN in many,Citation1,Citation5,Citation9 but not in allCitation5,Citation11–Citation13studies. However, few studies have documented the response rates to the current Peg-IFNα and RBV therapy. The aim of our study was to assess the prevalence of OBI in the serum of Egyptian patients with CHC, and to evaluate its impact on the response to treatment with a combination of Peg-IFNα and RBV.

2 Materials and methods

Fifty chronic HCV infected patients who were treated with 180 μg Peg-IFNα-2a or 1.5 μg/kg Peg-IFNα-2b once a week in combination with RBV (800–1400 mg/day) for 48 weeks were included in this study.Citation14,Citation15 Those patients were selected from the outpatient clinic of the Medical Research Institute, Alexandria University who were eligible and fulfilling the criteria for treatment with combined Peg-IFNα and RBV and followed up for 48 weeks of treatment. PCR- HCV was done at 0 and 48 weeks of the treatment and after 24 weeks of the end of treatment where the patients were divided into 2 groups; group I which included 25 patients who achieved SVR and group II that included 25 patients who failed to achieve SVR (Non-SVR). Before enrollment in the study both patient groups were subjected to detailed questionnaire, clinical examination and the following laboratory investigations: (a) biochemical studies (ALT, AST and Bilirubin)Citation16 (b) hematological studies (Prothrombin activity and Platelets count)Citation17 (c) virological studies that included: Anti-HCV antibodies and HCV-RNA (0, 48 and 72 week). After selection of both patient groups other virological studies were done that included: serological detection of anti-HBc antibodies, Murex anti-HBc total (Murex Diagnostics, Chicago, IL)Citation18 and detection of HBV-DNA (s and c genes) by the SYBR Green technique,Citation19 pol gene by the nested PCR technique.Citation20

Anti-HCV antibodies, third generation ELISA kits (MUREX ANTI-HCV (VERSION 4) MUREX BIOTECH.)Citation18

HCV-RNA extraction was done using QIAamp viral RNA Mini kits (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For the quantitative detection of HCV-RNA, it was amplified by using (Artus HCV QS-RGQ PCR Kit) reagents based on the amplification and simultaneous detection of a specific region of the HCV genome using real-time RT-PCR with TaqMan probe assay. The amplification reaction was performed as follows; 6 μl of HCV RG Master A, 9 μl of HCV RG Master B and 10 μl of Qiagen extracted RNA were added to bring the reaction to a final volume of 25 μl. Real-time PCR was performed with the Mx3000P TM (Stratagene) real-time PCR system. The reaction took place under the following thermal profile; incubation at 50 °C for 30 min to transcribe viral RNA to complementary DNA (cDNA) by RT. This was followed by AmpliTaq gold activation at 95 °C for 10 min, then 45 cycles of three PCR-step amplification, denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, followed by annealing at 50 °C for 1 min and extension at 72 °C for 30 s, with end point fluorescence detection.

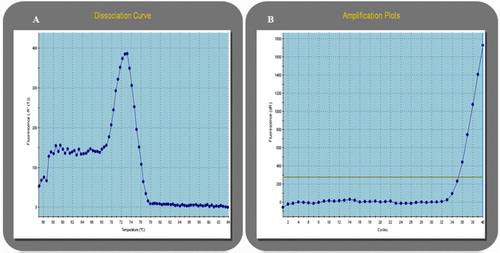

HBV-DNA extraction was done using QIAamp DNA Blood Mini kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The detection of HBV-DNA by SYBR Green real-time PCR (GeneON GmbH) assay was based on the specific amplification of HBV-DNA using primers targeting the s and c-gene and detection in real-time with SYBR Green dye (GeneON Gmb HSYBR Green PCR Kits). The amplification reaction was performed as follows; HBV s and c-gene were amplified by using 30 pmol of HBV s and c-gene sense and antisense primers with 12.5 μl SYBR Green universal PCR master mix 2-fold (GeneON GmbH) and 10 μl of Qiagen extracted DNA. H2O was added to bring the reaction to a final volume of 25 μl. real-time PCR was performed using the Mx3000P TM (Stratagene) real-time PCR system. The amplification profile was done as the following; AmpliTaq activation at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of PCR amplification, including denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s, annealing at 55 °C for 30sec and extension at 72 °C for 1 min. A melting curve analysis was done to determine the purity and specificity of the amplification product.

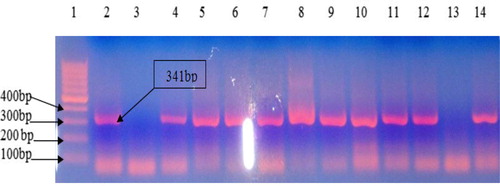

HBV-DNA extraction was done using QIAamp DNA Blood Mini kit (Qiagen). Detection of HBV-DNA was done by nested PCR using specific primers for pol genes. The outer primers (first round of PCR) used in this test amplify part (domain B and C) of the HBV polymerase gene. The amplified product of the first round PCR was targeted by nested (inner) primers. Nested amplification products were 341 bp long, analyzed on a 2% agarose gel, and visualized by staining with Ethidium Bromide (EtBr) at 302 nm. The outer amplification reaction components consisted of; 30 pmol of HBPr134 sense and HBPr135 antisense primers, 12.5 μl universal PCR master mix 2-fold (GeneOn GmbH), 10 μl of Qiagen extracted DNA and H2O was added to bring the reaction to a final volume of 25 μl.

The nested amplification components contained 30 pmol of HBPr75 sense and HBPr 94 antisense primer, 12.5 μl universal PCR master mix 2-fold (GeneON GmbH), 3 μl of outer amplified products and H2O was added to bring the reaction to a final volume of 25 μl. The thermal profile was performed as follows; outer amplification profile containing AmpliTaq activation at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of PCR amplification, including denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 45 °C for 30 s and extension at 72 °C for 30 s. then the final elongation at 72 °C for 10 min. Nested amplification thermal profile was similar to the outer amplification profile (35 cycles) (see and ).

Table 1 Sequences of primer pairs used for PCR to detect HBV genome.

Table 2 Sequences of primer pairs used for PCR to detect HBV genome.

3 Results

Among the 50 HCV patients included in this study 52% were males and 48% were females (). No significant difference was found in sex distribution regarding SVR and Non-SVR. shows that HCV viral load before treatment (at 0 week) was significantly associated with SVR. Fifteen patients (60%) out of 25 SVR patients had a viral load below 800,000 IU/mL compared to eight (32%) of the Non-SVR patients. shows that 11 (22%) out of 50 patients included in the study were anti-HBc positive. anti-HBc seropositivity was 36% of the Non-SVR HCV group compared to 8% of the SVR group, this was found to be statistically significant.

Table 3 Sex distribution among the 50 HCV patients.

Table 4 HCV viral load in SVR and Non-SVR HCV patients.

Table 5 Distribution of anti-HBc among the 50 HCV patients.

By comparing the detection of HBV-DNA by conventional nested PCR (pol gene) in relation to the real-time SYBR Green technique (s and c genes) we found that, out of 11 anti-HBc positive samples, 10 (90.9%) were positive for the pol and s genes while 9 (81.81%) were positive for the c gene (; and ). Among the 17 HBV-DNA positive HCV patients 70.6% were Non-SVR patients while the remaining 29.4% were SVR patients. This was found to be statistically significant ().

Figure 1 Detection of HBV s gene by SYBR Green. (A) Dissociation curve of s gene. (B) Amplification plot of s gene showing a Ct of 35 cycles.

Figure 2 Gel electrophoresis of nested PCR of pol gene. The 15 μl of PCR product was run on 2% agarose gel at 100 V for 1 h. Lane 1: DNA ladder −100 bp, Lane 2: positive control, Lane 3: negative control, Lane 4–12 and 14: positive samples and Lane 13: negative sample.

Table 6 Detection of HBV-DNA in 11 anti-HBc positive samples using conventional and real-time PCR techniques.

Table 7 Distribution of HBV-DNA positivity among SVR and Non-SVR HCV patients.

4 Discussion

There is general agreement that patients infected with HCV should be considered as a category of individuals with high prevalence of occult hepatitis B.Citation21 The incidence of OBI in HCV patients varies greatly, ranging from 0% to 52%.Citation12 In our study; 34% of HCV patients were positive for OBI. Our results were in agreement with those reported among Mediterranean countries since HBV-DNA was detectable in about one-third of HBsAg negative persons infected with HCV in the Mediterranean basin.Citation22,Citation23

Mrani et al.Citation1 reported that HBV-DNA was found in 1/4 of French chronic hepatitis C patients regardless of the presence of anti-HBc. Such an occult HBV co-infection was associated with more severe liver disease, higher HCV viral load and decreased response to antiviral therapy irrespective of HCV genotypes. Fukuda et al.Citation24 and Liu et al.Citation25 reported that the serum titer of HCV-RNA was visibly higher in patients with concurrent HBV and HCV infection than those with HCV mono-infection. Mrani et al.Citation1 also found that HCV viral load was significantly higher in HBV-DNA positive than in negative patients. Emara et al.Citation12 reported that this seemed to be applicable to genotype 4, where HBV-DNA positive patients in their study showed higher baseline HCV viral load than HCV mono-infected patients. Our results agree with these results as 82.4% of our HBV-DNA positive patients were associated with high HCV viral load compared to 39.4% of HBV-DNA negative and this was statistically significant.

Early studies reported a higher prevalence of HBV-DNA detection in anti-HBc-positive than in anti-HBc-negative patients.Citation24,Citation26 In his study, Marusawa et al.Citation27 found that the prevalence of anti-HBc is almost 50% in patients with HCV related chronic liver disease. In the present study 34% of our HCV cases were positive for HBV-DNA of whom 58.8% were anti-HBc positive. Chemin et al.Citation28 reported that occult HBV infection was most frequently seen in patients with anti-HBc as the only HBV serological marker. On the opposite, Mrani et al.Citation1 found that OBI was not associated with the presence of anti-HBc in chronic HCV patients.

Ramia et al.Citation29 found that the overall rate of HBV-DNA in the HCV-infected patients was 16.3%, compared to the HBV-DNA rate of 41% in HCV-infected patients who were anti-HBc alone positive. Our results agree with Ramia et al.Citation29since 22% of the 50 HCV patients were anti-HBc positive of whom 90.9% were HBV-DNA positive, on the other hand 78% were anti-HBc negative of whom only 17.9% were positive for HBV-DNA.

The finding of OBI among anti-HBc positive persons supports the notation that OBI is frequently a late phase of overt chronic HBV infection or serologically recovered acute HBV infection. Another possible hypothesis for this finding is that HCV infection may block the circulating viral expression of HBV but anti-HBc in the serum and HBV-DNA in the hepatocytes may persist.Citation30 Also persistence of low levels of HBV-DNA in the absence of detectable HBsAg may be due to host and viral factors suppressing viral replication and keeping the infection under control.Citation7

Few studies however evaluated the impact of occult hepatitis B infection on the current standard treatment of HCV infection, that is, combination of Peg-IFNα and RBV.Citation21 Caviglia et al.Citation11 concluded that despite the high prevalence rate of liver HBV DNA in patients with CHC, SVR was not affected by occult HBV infection. Kao et al.Citation19 reported that the sustained rates of response to combined alpha IFN and RBV therapy were similar between chronic HCV patients with OBI and those without OBI, and thus, low-level HBV infection did not interfere with the response to combination therapy against HCV. Kishk et al.Citation31 reported that exposure to HBV or occult HBV infection in patients with chronic HCV does not affect the outcome of therapy at weeks 12 and 24.

By contrast, Mrani et al.Citation1 reported that sustained response to IFN and RBV was achieved in 11 (28%) of 40 HBV-DNA positive cases with chronic hepatitis C, compared with 65 (45%) of the 144 HBV-DNA negative cases (P < 0.05). Cacciola et al.Citation9 reported that the occult HBV was detected in 26 of 55 patients in whom IFN therapy was unsuccessful and in 7 of 28 patients in whom treatment was successful. In the present study, SVR was achieved in 60.6% of the HBV-DNA negative chronic HCV patients compared to only 29.4% of the occult HBV chronic HCV patients. This was statistically significant.

The serological pattern consisting of “anti-HBc alone”, namely anti-HBc without both HBsAg and anti-HBs, has gained increased attention as a possible marker of OBI. The emerging generally accepted concept is that there is a significant, but not absolute, correlation between persistence of OBI and anti-HBc.Citation32 Our findings were in agreement with the previous investigations since out of the 11 anti-HBc positive CHCV patients 10 (90.9%) were OBI. Ocana et al.Citation33 suggested that anti-HBc determination is useful in OBI diagnosis, even when HBV-DNA is available, because of the possibility of intermittent viremia. Also, the Taormina group recommended its use as a surrogate marker whenever an HBV-DNA test is not available to identify potential sero-positive OBI individuals.Citation33

5 Conclusion

The prevalence of OBI was higher in our CHC patients. OBI was significantly associated with poor response to combined Peg-IFNα and RBV therapy.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Notes

Peer review under responsibility of Alexandria University Faculty of Medicine.

Available online 7 January 2015

References

- S.MraniI.CheminK.MenouarO.GuillaudP.PradatG.BorghiOccult HBV infection may represent a major risk factor of non-response to antiviral therapy of chronic hepatitis CJ Med Virol79200710751081

- F.D.MillerL.J.Abu-RaddadEvidence of intense ongoing endemic transmission of hepatitis C virus in EgyptProc Natl Acad Sci U S A10720101475714762

- A.R.El-ZayadiE.H.IbrahimH.M.BadranA.SaeidN.A.MoneibM.A.ShemisAnti-HBc screening in Egyptian blood donors reduces the risk of hepatitis B virus transmissionTransfus Med1820085561

- A.El-SherifM.Abou-ShadyH.Abou-ZeidA.ElwassiefA.ElbahrawyY.UedaAntibody to hepatitis B core antigen as a screening test for occult hepatitis B virus infection in Egyptian chronic hepatitis C patientsJ Gastroenterol442009359364

- C.M.Fernandez-RodriguezM.L.GutierrezJ.L.LledoM.L.CasasInfluence of occult hepatitis B virus infection in chronic hepatitis C outcomesWorld J Gastroenterol17201115581562

- P.HabibollahiS.SafariN.E.DaryaniS.M.AlavianOccult hepatitis B infection and its possible impact on chronic hepatitis C virus infectionSaudi J Gastroenterol152009220224

- F.B.HollingerG.SoodOccult hepatitis B virus infection: a covert operationJ Viral Hepat172010115

- A.ValsamakisMolecular testing in the diagnosis and management of chronic hepatitis BClin Microbiol Rev202007426439

- I.CacciolaT.PollicinoG.SquadritoG.CerenziaM.E.OrlandoG.RaimondoOccult hepatitis B virus infection in patients with chronic hepatitis C liver diseaseN Engl J Med34119992226

- H.J.YuanW.M.LeeNonresponse to treatment for hepatitis C: current management strategiesDrugs6820082742

- G.P.CavigliaM.L.AbateP.ManziniF.DanielleA.CiancioC.RossoOccult hepatitis B virus infection in patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with antiviral therapyHepat Mon12112012e7292

- M.H.EmaraN.E.El-GammalL.A.MohamedM.M.BahgatOccult hepatitis B infection in Egyptian chronic hepatitis C patients: prevalence, impact on pegylated interferon/ribavirin therapyVirol J72010324

- K.Q.HuOccult hepatitis B virus infection and its clinical implicationsJ Viral Hepat92002243257

- S.M.KamalS.S.El KamaryM.D.ShardellM.HashemI.N.AhmedM.MuhammadiPegylated interferon alpha-2b plus ribavirin in patients with genotype 4 chronic hepatitis C: the role of rapid and early virologic responseHepatology46200717321740

- I.M.JacobsonR.S.BrownJr.B.FreilichN.AfdhalP.Y.KwoJ.SantoroPeginterferon alfa-2b and weight-based or flat-dose ribavirin in chronic hepatitis C patients: a randomized trialHepatology462007971981

- C.A.BurtisE.R.AshoodD.E.BrunsTietz fundamentals of clinical chemistry6th ed.2008Elsevier Saunders CompanySt Louis323325

- B.BainI.BatesM.LaffanM.LewisBasic haematological techniquesJ.V.DacieS.M.LewisPractical haematology11th ed.2011Churchill LivingstoneEdinburgh3348

- A.M.CourouceDevelopment of screening and confirmation tests for antibodies to hepatitis C virusCurr Stud Hematol Blood Transfus19986475

- J.H.KaoP.J.ChenM.Y.LaiD.S.ChenOccult hepatitis B virus infection and clinical outcomes of patients with chronic hepatitis CJ Clin Microbiol40200240684071

- L.StuyverC.Van GeytS.De GendtG.Van ReybroeckF.ZoulimG.Leroux-RoelsLine probe assay for monitoring drug resistance in hepatitis B virus-infected patients during antiviral therapyJ Clin Microbiol382000702707

- M.LevastS.LarratM.A.TheluS.NicodA.PlagesA.CheveauPrevalence and impact of occult hepatitis B infection in chronic hepatitis C patients treated with pegylated interferon and ribavirinJ Med Virol822010747754

- Shereen E.TahaSoha A.El-HadyTamer M.AhmedIman Z.AhmedDetection of occult HBV infection by nested PCR assay among chronic hepatitis C patients with and without hepatocellular carcinomaEgypt J Med Hum Genet142013353360

- G.RaimondoT.PollicinoI.CacciolaG.SquadritoOccult hepatitis B virus infectionJ Hepatol462007160170

- R.FukudaN.IshimuraM.NiigakiS.HamamotoS.SatohS.TanakaSerologically silent hepatitis B virus coinfection in patients with hepatitis C virus-associated chronic liver disease: clinical and virological significanceJ Med Virol581999201207

- C.J.LiuW.L.ChuangC.M.LeeM.L.YuS.N.LuS.S.WuPeginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for the treatment of dual chronic infection with hepatitis B and C virusesGastroenterology1362009496504

- W.JilgE.SiegerR.ZachovalH.SchatzlIndividuals with antibodies against hepatitis B core antigen as the only serological marker for hepatitis B infection: high percentage of carriers of hepatitis B and C virusJ Hepatol2319951420

- H.MarusawaY.OsakiT.KimuraK.ItoY.YamashitaT.EguchiHigh prevalence of anti-hepatitis B virus serological markers in patients with hepatitis C virus related chronic liver disease in JapanGut451999284288

- I.CheminD.JeantetA.KayC.TrepoRole of silent hepatitis B virus in chronic hepatitis B surface antigen(−) liver diseaseAntiviral Res522001117123

- S.RamiaA.I.ShararaM.El-ZaatariF.RamlawiZ.MahfoudOccult hepatitis B virus infection in Lebanese patients with chronic hepatitis C liver diseaseEur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis272008217221

- B.ZöllnerH.-H.FeuchtM.SterneckH.SchäferX.RogiersL.FischerClinical reactivation after liver transplantation with an unusual minor strain of hepatitis B virus in an occult carrierLiver Transp12200612831289

- R.KishkH.Aboul AttaM.RaghebM.KamelL.MetwallyN.NemrGenotype characterization of occult hepatitis B virus strains among Egyptian chronic hepatitis C patientsEast Mediterr Health J20120141016

- S.UrbaniF.FagnoniG.MissaleM.FranchiniThe role of anti-core antibody response in the detection of occult hepatitis B virus infectionClin Chem Lab Med4820102329

- S.OcanaM.L.CasasI.BuhigasJ.L.LledoDiagnostic strategy for occult hepatitis B virus infectionWorld J Gastroenterol17201115531557