Abstract

Background

Concurrent infections with hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) are increasingly recognized in patients with chronic hepatitis. In Egypt, the last decade showed a remarkable decline in HBV infection associated with remarkable rise in HCV infection. The probable impact of occult HBV in patients with chronic HCV infection has been previously investigated and the evidence suggests a possible correlation with lower response to anti-viral treatment, higher grades of liver histological changes, and development of hepatocellular carcinoma. The aim of this study was to analyze the possible influence of occult HBV infection on the clinical outcomes in chronic HCV patients and to compare conventional and real-time PCR in detecting HBV DNA among Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) negative chronic HCV.

Methods

Sera collected from 100 chronic HCV patients (negative for HBsAg and positive for anti-HCV and HCV RNA) were tested for anti-HBc, anti-HBe and anti-HBs by ELISA, HCV-RNA viral load was determined by real-time PCR (TaqMan probe technique) and HBV DNA was detected with primers encoding the surface (S), core (C), polymerase (pol) and X genes. In addition, determination of liver enzymes including aspartate and alanine aminotransferases (AST, ALT) activities was performed.

Results

Fifty-eight percent of the study group were positive for anti-HBc. Meanwhile, only 18 cases (18%) were positive for the polymerase gene by nested PCR and were considered as occult HBV. Among these 18 polymerase gene positive patients (occult HBV) anti-HBc was detected among 9 (50%) of cases. Different gene profiles were noticed among the 18 polymerase gene positive patients.

1 Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections account for a substantial proportion of cases of chronic liver disease including chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and liver cancer. Citation1 It is estimated that there are 240 million HBV carriers and 130–150 million HCV carriers worldwide. Citation2,Citation3 HBV and HCV are transmitted parenterally and share common routes of infection; as a result, infection with both viruses may occur. Citation1

The diagnosis of HBV infection is usually based on the detection of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), and the disappearance of this antigen indicates the clearance of HBV. Citation4 However, it has been shown that HBV DNA can be detected in patients with chronic liver disease who are negative for HBsAg but positive for antibodies to hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc). This so-called occult HBV (OBI) infection has frequently been identified in patients with chronic HCV infection. Citation5,Citation6

More recently, occult HBV infection has been considered to play a role in chronic hepatitis C virus infected patients, including the severity of HCV, related liver disease, poor response to anti-HCV treatment and development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Citation7–Citation9

Owing to their distinct clinical course and heterogeneity, identification of patients who are candidates for therapy and selection of the optimal antiviral therapy is a challenge for clinicians.

The aim of this work was to study the possible influence of occult HBV infection on the clinical outcomes in the HBsAg negative chronic HCV patients and to compare conventional and real-time PCR in detecting HBV DNA among infected patients.

2 Patients and methods

A cross-sectional study was carried out, it included 100 consecutive patients (negative for HBsAg and positive for anti-HCV and HCV RNA) attending the Hepatology outpatient clinic and diagnosed by the Microbiology Department in Medical Research Institute, Alexandria, Egypt.

The study was carried out after receiving the approval of the Ethics Committee in the Medical Research Institute. All relevant information was collected from patients (after taking full consent) including personal data.

Sera were collected from all cases and were tested for antibodies against hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc), antibodies against hepatitis B e antigen (anti-HBe), antibodies against hepatitis B s antigen (anti-HBs) (Abbott Murex Diagnostic Division, Dartford, Kent, U.K) and determination of liver enzymes; aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), total serum bilirubin and serum albumin. Citation10,Citation11

2.1 Quantitative detection of HCV RNA by real-time PCR

RNA extraction: RNA was extracted from serum specimens using a QIAamp viral RNA kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, California, USA) following manufacturer’s instructions. Ten μl of extracted RNA was amplified by using 6 μl of HCV RG Master A and 9 μl of HCV RG Master B to bring the reaction to a final volume of 25 μl, with the PCR MX3000 stratagene (Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster city, California, USA) system. Thermal Profile of amplification included the following: 50 °C for 30 min (reverse transcriptase step) followed by Ampli Taq activation step at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by a three step PCR protocol: 95 °C for 30 s and followed by annealing at 50 °C for 1 min and extension at 72 °C for 30 s, for 40 cycles with end point fluorescence detection.

2.2 Detection of HBV DNA

2.2.1 HBV DNA extraction

DNA was extracted from serum using QIAamp viral DNA mini kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA, United States) following manufacturer’s instructions.

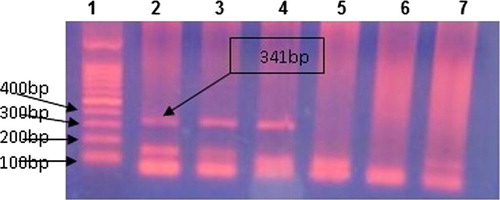

2.2.2 Detection of HBV-DNA by nested PCR using specific primers for pol gene Citation11

Outer amplification components included the following: 0.3 μl (30 pmol) of each of; outer primers, 12.5 μl universal PCR master mix 2-fold (GeneOn GmbH), 10 μl of Qiagen extracted DNA and H2O was added to bring the reaction to a final volume of 25 μl. The DNA was amplified using the following profile: Ampli Taq activation for 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of PCR amplification; denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 45 °C for 30 s and extension at 72 °C for 30 s followed by final elongation at 72 °C for 10 min.

Nested amplification components included the following: 3 μl of outer amplified products to be re-amplified using 0.3 μl (30 pmol) of each of; inner primers, 12.5 μl universal PCR master mix 2-fold (GeneOn GmbH), and H2O was added to bring the reaction to a final volume of 25 μl. The second round amplification profile was similar to the first round but only 35 cycles were carried out.

After amplification, Ethidium bromide stained, 2% agarose gel was prepared in TAE (Tris–acetate–EDTA, PH 8) buffer and used for detection of the 341 base pair positive band. Fifteen μl of PCR product was run on 2% agarose gel at 100 V for 45 min. A 100 bp DNA marker was used to identify the amplified bands.

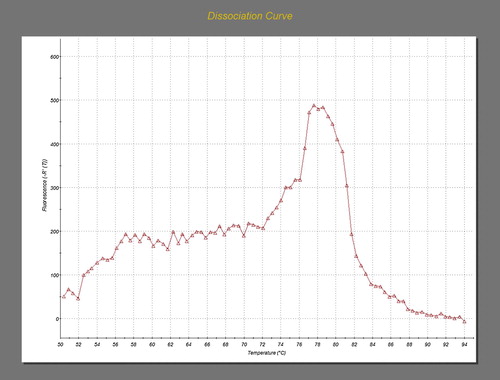

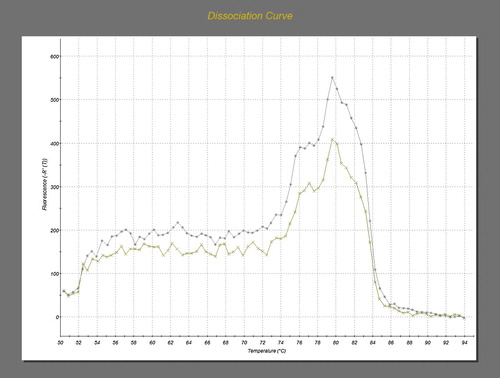

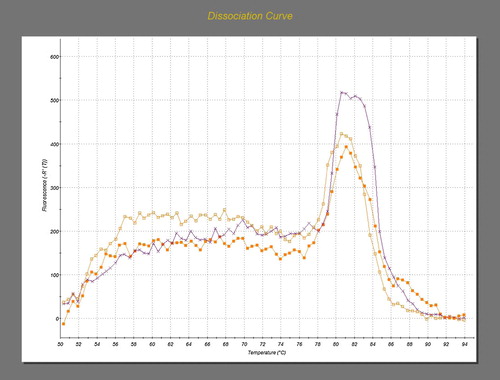

2.2.3 Amplification of S, C and X genes of HBV by SYBR green real-time PCR (AB: Applied Biosystem) using specific primers Citation12

The amplification reaction was performed as follows:

For amplification of each gene: 0.3 μl (30 pmol) of HB s or c, or x gene sense and antisense primers, 12.5 μl syber green universal PCR master mix 2-fold (AB applied biosystem, United States), 10 μl of Qiagen extracted DNA and H2o was added to bring the reaction to a final volume of 25 μl. After AmpliTaq activation at 95 °C for 10 min, the DNA was amplified for 40 cycles of PCR amplification. Each cycle entailed: denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s, annealing at 55 °C for 30 s and extension at 72 °C for 1 min. This was followed by melting curve analysis to determine the purity and specificity of the amplification product. The melting curve analysis profile was 95 °C for 1 min, 50 °C for 30 s, and 95 °C for 15 s.

3 Results

The 100 anti-HCV positive patients included in this study included 64 (64%) males and 36 (36%) females, with a male to female ratio of 1.7:1. Their age ranged from (20–60) years. Forty-five percent of them were in the (31–40) age group.

3.1 HCV RNA viral load

The majority of the 100 anti-HCV patients (85%) had high viremia (105–108) IU/mL, meanwhile, only (15%) had low level viremia of less than 104 IU/ml. High HCV viral load (above 105) was highly associated with abnormal liver functions ().

Table 1 Correlation between HCV RNA viral load, with abnormal liver functions among the 100 anti-HCV positive cases:

3.2 Occult HBV OR pol gene

Out of the 100 HCV RNA positive HBsAg negative patients, 58% were positive for anti-HBc. Meanwhile, only 18 cases (18%) were positive for the polymerase gene by nested PCR and were considered as occult HBV. Among the 18 polymerase gene positive patients (occult HBV, OBI) anti-HBc was detected among 9 (50%) of cases ().

3.3 Co HCV/HBV infection

94.5% of patients with dual HCV/occult-HBV infection had HCV RNA viral load of 105–106 IU/ml, compared to 80% of patients with single HCV infection. No significant association was found between HCV viral load and pol gene positivity. Interestingly 77% and 55% of the patients with dual HCV/ occult-HBV infection had abnormal AST and ALT respectively, compared to 57% and 38% among patients with single HCV infection.

3.4 S, X and C genes

The 100 HCV positive patients were tested for the S, X and C genes by using SYBR Green real time, followed by dissociation curve analysis. Different gene profiles were noticed among the 18 polymerase gene positive patients with occult HBV infection. No significant association was found between the different gene profiles and abnormal AST and ALT levels (, –).

Table 2 Distribution of S, X, C and pol genes profile and liver enzymes among the 100 HCV positive patients.

3.5 Correlation between anti-core positivity, liver function tests and HCV viral load

The anti-core positivity was not significantly associated with the different liver functions. As, out of the 18 OBI patients, no difference among anti-HBc positive and anti-HBc negative patients was found as; 77.8% and 55.5% of either groups had elevated AST and ALT respectively ().

Table 3 Distribution of liver function tests and anti-HBc among the 18 OBI patients.

No significant association was noticed between anti-HBc positivity and HCV viral load as; 100% of anti-core positive compared to 89% of anti-core negative patients had HCV-RNA level of >105 IU/mL). However, only 11% of anti-core negative patients showed low HCV viremia (⩽104 IU/ml).

4 Discussion

HBV infection is one of the major global health problems. Worldwide, HBV is the primary cause of cirrhosis and HCC and is one of the ten leading causes of death. Citation13

Occult HBV infection has frequently been identified in patients with chronic HCV infection. Citation14,Citation15 This occult infection may be associated with more severe liver damage and even the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Citation16,Citation17

This study included 100 HCV RNA positive patients; 64 (64%) were males, 36 (36%) females, with a male to female ratio of 1.7:1. The age of the study group ranged from (20–60) years, 45% of them were in the (31–40) age group. The majority of anti-HCV patients (85%) had high viremia (>105 IU/ml), meanwhile, only (15%) had low level viremia of (⩽105 IU/ml). Abnormal serum ALT and AST were found to be statistically associated with high HCV viral load.

As viral DNA levels in occult hepatitis B are very low, the identification of occult hepatitis B is strongly dependent on both the sensitivity and the specificity of the assay. Current technologies used for DNA detection are as follows: nested-PCR, real-time PCR, and transcription mediated amplification (TMA). Primers must be specific for different HBV genomic regions and complementary to highly conserved (genotype shared) nucleotide sequences. Citation11,Citation18

Based on several studies, conventional nested PCR using specific primers targeting the pol gene was found to be a highly sensitive technique for detection of OBI. Citation19 Based on these data, the 100 chronic HCV patients enrolled in the current study were tested for anti-HBc and pol gene was amplified using nested PCR.

In this specific high-risk group, several studies have been conducted worldwide. The available data on the frequency of occult HBV infection are widely divergent. OBI seems to be highly prevalent in Asia. Citation20 Although the prevalence of occult hepatitis B in patients with chronic hepatitis varies, the highest prevalence is among hepatitis C patients. Citation21 There is general agreement that patients infected with HCV should be considered as a category of individuals with high prevalence of occult hepatitis B. Citation22 The incidence of OBI in HCV patients varies greatly, ranging from 0% to 52%. Citation23

In the current study, out of the 100 CHC patients 18 cases (18%) were positive for the pol gene by nested PCR (OBI). Similar results were reported in several studies. Citation24–Citation28 Also, our results agree with that reported among Mediterranean countries since HBV-DNA was detectable in about one-third of HBsAg negative HCV carriers in the Mediterranean basin. Citation29,Citation30

In 2011, Selim et al., Citation25 repotted that 23 (38.3%) of 60 chronic Egyptian hepatitis C patients had detectable HBV-DNA, despite the absence of circulating HBsAg.

In Lebanon, an overall rate of 16.3% of occult HBV was detected among chronic HCV patients. Citation30 Georgiadou et al., Citation31 demonstrated that almost one quarter of HCV-positive/HBsAg-negative Greek patients had detectable HBV-DNA by PCR. Higher prevalence was reported in Far East Asian countries by using PCR, as the prevalence of OBI in Chinese patients with chronic HCV infection was 41.9%. Citation32

The difference in the reported prevalence may be due to a multitude of reasons. This difference is attributed mainly to geographical variation regarding HBV endemicity in these countries. Risk factors for hepatitis B infection and the biomarkers of hepatitis B infection are different in the studied populations, and also, different in terms of sensitivity and detection limit of the assay used (standard/nested PCR, real-time PCR, etc.). The number of HBV DNA domains examined and the biological compartment explored (liver, plasma, or both) play an important role.

There have been significant advances in understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying occult HBV infection in the last decade; the stability and long-term persistence of viral covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) molecules together with the long half-life of hepatocytes imply that HBV infection, once it has occurred, may possibly continue for life. There is persistence of low HBV-DNA levels and lack of detectable HBsAg in patients with OBI remains largely unknown although the condition is probably multifactorial. Both host and viral factors may be involved. Citation29–Citation34

Among the host factors, the host immune response may play a role in keeping viral replication at low levels characteristic of OBI or hindrance of HBsAg through circulating immune complex. Likewise, hepatic cytokines such as TNF-α and IFN-β may inhibit viral replication and activation. Meanwhile, reduced HBV viremia may result from extra-hepatic HBV replication such as that takes place in polymorph-nuclear cells (PBMCs). Patients with long-standing abnormal results of liver function tests with unknown etiology may have HBV-DNA in their PBMCs in the absence of HBV markers, serum HBV-DNA. Citation35

Regarding viral factors any mutation that changes the antigenicity of the HBsAg or that decreases the synthesis of this antigen or blockage of free HBsAg secretion may be the cause of the lack of detection of HBsAg in patients with OBI (HBV variants). Citation36 Additional mechanisms for OBI have been thoroughly investigated, emphasizing that integration of viral sequence may alter HBsAg expression and decrease HBV replication. Mutations in the regulatory regions of the HBV genome or the polymerase domain or in the s gene cause HBsAg to be undetectable by commercial assays. Citation11,Citation37

Early studies reported a higher prevalence of HBV-DNA detection in anti-HBc-positive than in anti-HBc negative patients. Citation38,Citation39 In this study the pol gene was equally detected among both anti-HBc positive (50%) and anti-HBc negative patients (50%).

Ramia S et al., Citation30 detected HBV DNA in 41% of anti-core positive patients compared to 7.1% of anti-core negative chronic HCV patients

Detection of HBV DNA from serum or liver samples is considered the gold standard for the diagnosis of occult HBV infection. Experts have recently recommended the use of highly sensitive nested PCR or real-time PCR assays that can detect fewer than 10 copies of HBV DNA for the diagnosis of occult HBV infection. In addition, testing for multiple targets on the HBV genome increases HBV DNA detection rates. Citation37

In the present study, we tested two technical procedures regarding their specificity and sensitivity: real-time PCR namely SYBR Green (amplifying S, C and X genes) and nested PCR with primers targeting the region encoding the pol gene.

Using three sets of primers, specific for HBV surface, core and X genes, different gene profiles were noticed among the 18 chronic HCV patients with occult HBV infection as follows: the 4 genes (pol, S, C, X) combination was only detected among one patient (5.5%), (pol, C, X) gene combination was detected in 4 patients (22.3%). However pol and S genes, pol and C genes and pol, X genes were detected solely in 2 patients (11%), 5 patients (27.8%), and one patient (5.5%) respectively. On the other hand, 5 cases (27.8%) positive for pol gene, were negative for the other 3 genes.

Different results were reported by Kader et al. Citation40 among Sudanese blood donors as there were two main profiles, namely the presence of the s, c, x genes together in 33.3% of the blood donors or the presence of x gene in addition to the core gene in 38% of their study group.

Our results disagree with those of Allice et al. Citation41 who reported that HBV Cobas TaqMan real-time PCR seems completely appropriate for exploration of occult hepatitis. Citation42

On the other hand, several studies reported that the use of COBAS TaqMan HBV PCR assay to screen OBI has not provided information similar to that reported using nested PCR. Citation43–Citation46 Fujiwara et al., Citation47 used a real-time PCR for quantitation of HBV-DNA. They reported that the detection rate was slightly lower than that in other studies using different techniques. The specificity of the results was usually enhanced by using nested PCR with two rounds of amplification and primers amplifying different targets.

The gold standard test for detection of OBI is the amplification of HBV-DNA. At present, the optimal standard for diagnosis is the analysis of HBV-DNA extracts performed by real-time, nested PCR techniques. False results of these assays could be avoided by choosing PCR primers that span at least three genomic regions of the HBV genome such as the s, x and c genes, and validation should require detection from at least two regions of the genome. This suggestion is not usually fulfilled, and only one segment of a region is amplified. Citation12,Citation34,Citation48

Patients with both HBV and HCV infections may show a large spectrum of virological profiles. Citation49 HCV infection can suppress HBV replication, as demonstrated by studies showing that patients with chronic hepatitis B who are coinfected with HCV have lower HBV-DNA levels, decreased activity of HBV-DNA polymerase, and decreased expression of HBsAg and HBcAg in the liver. Citation50,Citation51 Moreover, patients with chronic HBV infection who become superinfected with HCV can undergo seroconversion of HBsAg. This effect may be mediated by the host immune response (via the induction of cytokines such as IFNs) or by a direct effect of HCV proteins. Direct interference mediated by HCV proteins can occur in vivo only if both HBV and HCV coexist in the same hepatocyte. Citation52

Several studies Citation53,Citation54,Citation15 emphasized on the clinical impact of silent HBV in patients suffering from chronic liver disease as a result of HCV and reported that higher levels of the liver disease severity were seen. It has been suggested that HBV replication accounts for many of the liver enzyme flares in patients co-infected with HCV and occult HBV, and is associated with fibrosis/cirrhosis. Citation55,Citation56 However, in the current study, no significant association was found between OBI and the liver function tests either in the anti-core positive or anti-core negative patients.

5 Conclusion

From this study we can conclude that occult hepatitis B is observed in a considerable number of hepatitis C patients in Egypt. Routine serological profiles are not always reliable in determining status of HBV infection. Prospective studies are also required to establish the relative risk of HCC among individuals with HBsAg negative chronic liver disease and HCV coinfection.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Notes

Peer review under responsibility of Alexandria University Faculty of Medicine.

Available online 12 September 2015

References

- Ding-Shinn Chen Jia-Horng Kao Pei-Jer Chen Ming-Yang Lai Hepatitis C clinical outcomes of patients with chronic hepatitis C J Clin Microbiol 40 11 2002 4068 4071

- World Health Organization. Hepatitis B. World Health Organization Fact Sheet N°204 (Revised March 2014). WHO Web site. World Health Organization, Hepatitis B. Fact sheet N°204; 2014. Available at: WHO Web site http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs204/en//.

- World Health Organization. Hepatitis C. World Health Organization Fact Sheet N°164 (Revised April 2014). WHO Web site. World Health Organization, Hepatitis C. Fact sheet N°164; 2014. Available at: WHO Web site http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs164/en//.

- S. Bowden New directions in molecular diagnostics for hepatitis B: serum and tissue-based diagnostics J Gastroenterol Hepatol 19 2004 S311 S314

- D. Shouval What is the clinical significance of the high prevalence of occult hepatitis B in US liver transplant patients with chronic hepatitis C Liver Transpl 14 2008 418 419

- Z. Honarkar S.M. Alavian S. Samiee K. Saeedfar M. Baladast M.J. Ehsani Occult Hepatitis B as a cause of cryptogenic cirrhosis Hepat Mon 4 2004 155 160

- S. Mrani I. Chemin K. Menouar O. Guillaud P. Pradat G. Borghi Occult HBV infection may represent a major risk factor of non-response to antiviral therapy of chronic hepatitis C J Med Virol 79 2007 1075 1081

- K. Shetty M. Hussain L. Nei K.R. Reddy A.S. Lok Prevalence and significance of occult hepatitis B in a liver transplant population with chronic hepatitis C Liver Transpl 14 2008 534 540

- J. Kleiber T. Walter G. Haberhausen S. Tsaung R. Babeil M. Rosenstaus Performance Characteristics of a Quantitative, Homogeneous TaqMan RT-PCR Test for HCV RNA J Mol Diagnos 2 3 2000 158 166

- F.B. Hollinger G. Sood Occult hepatitis B virus infection: a covert operation J Viral Hepat 17 2010 1 15

- J.H. Kao P.J. Chen M.Y. Lai D.S. Chen Occult hepatitis B virus infection and clinical outcomes of patients with chronic hepatitis C J Clin Microbiol 2002 4068 4071

- F.B. Hollinger T.J. Liang Hepatitis B virus D.M. Knipe Fields virology 4th ed. 2001 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Philadelphia 2971 3036

- E. Sagnelli N. Coppola C. Scolasticoc Virologic and clinical expression of reciprocal inhibitory effect of hepatitis B, C, and delta viruses in patients with chronichepatitis Hepatology 32 2000 1106 1110

- J.P. Allain Occult hepatitis B virus Transfus Clin Biol 11 2004 11 25

- I. Cacciola T. Pollicino G. Squadrito G. Cerenzia M.E. Orlando Occult hepatitis B. Virus infection in patients with chronic hepatitis C liverdisease N Engl J Med 341 1999 22 26

- H. Yotsuyanagi Y. Shintani K. Moriya H. Fujie Virologic analysis of non-B, non-C hepatolcellular carcinoma in Japan: frequent involvement of hepatitis B virus J Infect Dis 181 2000 1920 1928

- S. Ocana M.L. Casas I. Buhigas J.L. Lledo Diagnostic strategy for occult hepatitis B virus infection World J Gastroenterol 17 2011 1553 1557

- L. Stuyver C. Van Geyt S. De Gendt G. Van Reybroeck F. Zoulim G. Leroux-Roels Line probe assay for monitoring drug resistance in hepatitis B virus-infected patients during antiviral therapy J Clin Microbiol 38 2000 702 707

- M. Torbenson D.L. Thomas Occult hepatitis B Lancet Infect Dis 2 8 2002 479 486

- G. Raimondo T. Pollicino I. Cacciola G. Squadrito Occult hepatitis B virus infection J Hepatol 46 1 2007 160 170

- M. Levast S. Larrat M.A. Thelu S. Nicod A. Plages A. Cheveau Prevalence and impact of occult hepatitis B infection in chronic hepatitis C patients treated with pegylated interferon and ribavirin J Med Virol 82 2010 747 754

- M.H. Emara N.E. El-Gammal L.A. Mohamed M.M. Bahgat Occult hepatitis B infection in Egyptian chronic hepatitis C patients: prevalence, impact on pegylated interferon/ribavirin therapy Virol J 7 2010 324

- A. Shavakhi B. Norinayer S.A. Esteghamat M. Seghatoleslami M. Khodadustan H.M. Somi Occult hepatitis B among Iranian hepatitis C patients JRMS 14 1 2009 13 17

- S. Saravanan V. Velu S. Nandakumar V. Madhavan U. Shanmugasundaram K.G. Murugavel Hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus dual infection among patients with chronic liver disease J Microbiol Immunol Infect 42 2009 122 128

- H.S. Selim H.A. Abou-Donia H.A. Taha G.I. El Azab A.F. Bakry Role of occult hepatitis B virus in chronic hepatitis C patients with flare of liver enzymes Eur J Intern Med 22 2011 187 190

- L. Kazemi-Shirazi D. Petermann C. Muller Hepatitis B virus DNA in sera and liver tissue of HBsAg negative patients with chronic hepatitis C J Hepatol 33 2000 785 790

- L.F. Mariscal E. Rodriguez-Inigo J. Bartolome I. Castillo N. Ortiz-Movilla C. Navacerrada Hepatitis B infection of the liver in chronic hepatitis C without detectable hepatitis B virus DNA in serum J Med Virol 73 2004 177 186

- G. Raimondo T. Pollicino I. Cacciola G. Squadrito Occult hepatitis B virus infection J Hepatol 46 2007 160 170

- T. Pollicino G. Squadrito G. Cerenzia I. Cacciola G. Raffa A. Craxi Hepatitis B virus maintains its pro-oncogenic properties in the case of occult HBV infection Gastroenterology 126 2004 102 110

- S. Ramia A.I. Sharara M. El-Zaatari F. Ramlawi Z. Mahfoud Occult hepatitis B virus infection in Lebanese patients with chronic hepatitis C liver disease Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 27 2008 217 221

- S.P. Georgiadou K. Zachou E. Rigopoulou C. Liaskos P. Mina F. Gerovasilis Occult hepatitis B virus infection in Greek patients with chronic hepatitis C and in patients with diverse nonviral hepatic diseases J Viral Hepat 11 2004 358 365

- C.K. Hui E. Lau H. Wu A. Monto M. Kim J.M. Luk Fibrosis progression in chronic hepatitis C patients with occult hepatitis B co-infection J Clin Virol 35 2006 209 218

- J.R. Larrubia Occult hepatitis B virus infection: a complex entity with relevant clinical implications World J Gastroenterol 17 2011 1529 1530

- Z.N. Said An overview of occult hepatitis B virus infection World J Gastroenterol 17 2011 1927 1938

- P. Habibollahi S. Safari N.E. Daryani S.M. Alavian Occult hepatitis B infection and its possible impact on chronic hepatitis C virus infection Saudi J Gastroenterol 15 2009 220 224

- P. Schmeltzer K.E. Sherman Occult hepatitis B: clinical implications and treatment decisions Dig Dis Sci 55 2010 3328 3335

- J. Samal M. Kandpal P. Vivekanandan Molecular mechanisms underlying occult hepatitis B virus infection Clin Microbiol Rev 25 2012 142 163

- R. Fukuda N. Ishimura M. Niigaki S. Hamamoto S. Satoh S. Tanaka Serologically silent hepatitis B virus coinfection in patients with hepatitis C virus-associated chronic liver disease: clinical and virological significance J Med Virol 58 1999 201 207

- W. Jilg E. Sieger R. Zachoval H. Schatzl Individuals with antibodies against hepatitis B core antigen as the only serological marker for hepatitis B infection: high percentage of carriers of hepatitis B and C virus J Hepatol 23 1995 14 20

- O. Kader A. Ghazal D.E. Metwally A. Elnour G. Yousif Detection of occult Hepatitis B virus infection among blood donors in Sudan J Egypt Pub Health Assoc 88 2013 14 18

- T. Allice F. Cerutti F. Pittaluga S. Varetto S. Gabella A. Marzano COBAS AmpliPrep-COBAS TaqMan hepatitis B virus (HBV) test: a novel automated real-time PCR assay for quantification of HBV DNA in plasma J Clin Microbiol 45 2007 828 834

- S. Chevaliez M. Bouvier-Alias S. Laperche J.M. Pawlotsky Performance of the Cobas AmpliPrep/Cobas TaqMan real-time PCR assay for hepatitis B virus DNA quantification J Clin Microbiol 46 2008 1716 1723

- M. Levast S. Larrat M.A. Thelu S. Nicod A. Plages A. Cheveau Prevalence and impact of occult hepatitis B infection in chronic hepatitis C patients treated with pegylated interferon and ribavirin J Med Virol 82 2010 747 754

- E. Sagnelli M. Imparato N. Coppola R. Pisapia C. Sagnelli V. Messina Diagnosis and clinical impact of occult hepatitis B infection in patients with biopsy proven chronic hepatitis C: a multicenter study J Med Virol 80 2008 1547 1553

- E. Khattab I. Chemin I. Vuillermoz C. Vieux S. Mrani O. Guillaud Analysis of HCV co-infection with occult hepatitis B virus in patients undergoing IFN therapy J Clin Virol 33 2005 150 157

- K. Shetty M. Hussain L. Nei K.R. Reddy A.S. Lok Prevalence and significance of occult hepatitis B in a liver transplant population with chronic hepatitis C Liver Transpl. 14 2008 534 540

- K. Fujiwara Y. Tanaka E. Orito T. Ohno T. Kato F. Sugauchi Lack of association between occult hepatitis B virus DNA viral load and aminotransferase levels in patients with hepatitis C virus-related chronic liver disease J Gastroenterol Hepatol 19 2004 1343 1347

- D. Candotti J.P. Allain Transfusion-transmitted hepatitis B virus infection J Hepatol 51 2009 798 809

- C. Saitta P. Pontisso M.R. Brunetto S. Fargion G.B. Gaeta G.A. Niro Virological profiles in hepatitis B virus/hepatitis C virus coinfected patients under interferon plus ribavirin therapy Antivir Ther 11 2006 931 934

- S.D. Crockett E.B. Keeffe Natural history and treatment of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus coinfection Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 4 2005 13

- R.S. Koff Hepatitis essentials 2011 Jones & Bartlett Publishersp.11–2

- E. Rodriguez-Inigo J. Bartolome N. Ortiz-Movilla C. Platero J.M. Lopez-Alcorocho M. Pardo Hepatitis C virus (HCV) and hepatitis B virus (HBV) can coinfect the same hepatocyte in the liver of patients with chronic HCV and occult HBV infection J Virol 79 2005 15578 15581

- Y. Miura A. Shibuya S. Adachi A. Takeuchi T. Tsuchihashi T. Nakazawa Occult hepatitis B virus infection as a risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis C in whom viral eradication fails Hepatol Res 38 2008 546 556

- P. Fabris D. Brown G. Tositti L. Bozzola M.T. Giordani P. Bevilacqua Occult hepatitis B virus infection does not affect liver histology or response to therapy with interferon alpha and ribavirin in intravenous drug users with chronic hepatitis C J Clin Virol 29 2004 160 166

- C.M. Fernandez-Rodriguez M.L. Gutierrez J.L. Lledo M.L. Casas Influence of occult hepatitis B virus infection in chronic hepatitis C outcomes World J Gastroenterol 17 2011 1558 1562

- A. El-Sherif M. Abou-Shady H. Abou-Zeid A. Elwassief A. Elbahrawy Y. Ueda Antibody to hepatitis B core antigen as a screening test for occult hepatitis B virus infection in Egyptian chronic hepatitis C patients J Gastroenterol 44 2009 359 364