Abstract

Cutaneous Leishmaniasis (CL) is a disease caused by an intracellular protozoa belong to the genus Leishmania, transmitted by the bite of a sandfly. It has diverse clinical presentation and may create a public health problem in endemic countries. CL is often confused with lepromatous leprosy, pimples and fungal dermatitis. This case is an isolated cutaneous variety in facial region which was mistaken and treated initially for fungal dermatitis and then for leprosy by local physicians. Smears examined from the skin lesion confirmed Leishmania amastigotes. The isolated localized CL may create confusion and its many differential diagnoses made delaying in the diagnosis.

1 Introduction

Leishmaniasis is a vector borne disease and caused by a kinetoplastid protozoan parasite. The parasite is transmitted from one patient to another through the bites of female sandfly, or occasionally through non-vector routes including congenital, blood transfusion, sexual, laboratory acquired and person-to-person.Citation1 Leishmaniasis can be divided into three forms varying in severity from spontaneously healing dermatological ulcers in Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) and destructive form of mucocutaneous leishmaniasis to fatal form of visceral leishmaniasis (VL). CL is seen throughout Africa, South America, Asia, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean regions. It has diverse clinical manifestations, which poses a public health problem in endemic countries.Citation2 This disease can affect the skin, viscera or mucocutaneous area. Often CL cases are mistaken for common dermatological disorders such as fungal infections, bacterial infections, eczema or chronic ulcers that may delay in diagnosis and treatment. In some cases, patients consult several doctors before CL diagnosis. This situation leads to delay in the exact diagnosis and inadvertent exposure to adverse events of inappropriate treatment. Here an isolated lesion over the face made a misdiagnosis for fungal dermatitis initially and then leprosy by local physicians for which patient had taken prolonged unnecessary treatment due to delay in diagnosis.

2 Case report

A 48 year old male from northeast part of India presented to Outpatient department of Otorhinolaryngology for non-healing skin lesions over the face (A and B). From history, it was found that he was treated by many physicians by multiple drugs since two years, initially for fungal dermatitis and then for leprosy but lesions were not healed. On examination there are several small painless papular lesions with indurations. The papular lesions are showing central ulceration with erythematous borders over the forehead and cheek. He had no significant medical history and patient was in good health. He had no history of fever, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly or weight loss which are typical of VL. There were no signs of neuropathy. General clinical examinations and routine blood investigations were within normal limit. HIV test was negative. Slit skin smears from facial lesions were stained with Ziehel-Nielsen stain and revealed negative for acid-fast bacilli.

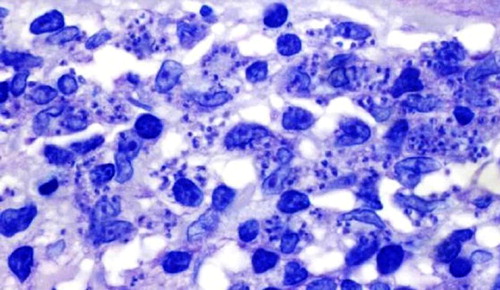

The biopsies and smears were taken from the facial lesions under the local anaesthesia and sent for histopathological examination. Light microscopy revealed skin with hyperkeratosis, acanthosis and parakeratosis. The dermis was invaded with large pink coloured histiocytes and chronic inflammatory cells. The histiocytes contained inside dot-like organisms typical of cutaneous leishmania (). He was treated with sodium stibogluconate for 3 weeks (intramuscular 20 mg/kg daily for 3 weeks). The cutaneous lesions of the face disappeared and there has been no evidence of recurrence after two years.

3 Discussion

Leishmaniasis is caused by unicellular, flagellate, intracellular protozoa belonging to the genus Leishmania transmitted from animals to humans through phlebotomine sandfly vectors. Common species of Leishmania responsible for CL in old world are L. major and L. tropica whereas L. mexicana, L. panamenesis and L. braziliensis in new world. The geographical distribution of Leishmaniasis is confined to temperate and tropical countries, the living area of the sandfly. Ninety percentages of cases of CL occur in Brazil, Afghanistan, Iran, Algeria, Peru, and Syria whereas visceral leishmaniasis is found in Bangladesh, India, Brazil, Nepal and Sudan.Citation3 In India, indigenous cases of CL are mainly confined to hot dry northwestern region and are endemic in the western Thar desert of Rajasthan.Citation4 Few cases have been observed in the states such as Kerala, Assam and Haryana.Citation5 Apart from this it was documented in northwestern part of Indo-Gangetic plain, along with dry areas of Indo-Pakistan border from Amritsar to Gujarat.Citation6 In southern part of India, CL has been reported from Malappuram and Trivandrum of Kerala.Citation7 The CL is usually caused by L. tropica and man is the most common reservoir in India.

Leishmaniasis has been considered tropical afflictions and constitutes one of the six entities in the World health organization/Tropical disease research (WHO/TDR) list of the most important diseases.Citation8,Citation9 Leishmaniasis is endemic in 88 countries of the five continents with total of 350 million people at risk and heaves 12 million cases. Out of the 88 endemic countries, 22 are in the New World and 66 in the Old World with an estimated incidence of 1–1.5 million cases of CL and 5 lakhs cases of visceral leishmaniasis (VL).Citation9 Even it has widespread geographical distribution, human leishmaniasis is often very focal within an endemic region, leading to ‘hotspots’ of the disease transmission.Citation5 Localized cutaneous lesions of leishmaniasis may resemble to other skin conditions such as lepromatous leprosy, cutaneous anthrax, blastomycosis, sporotrichosis, eczema, fungal skin infections, Mycobacterium marinum infections, sarcoidosis and infected insect bites. Isolated cutaneous lesion of leishmaniasis over the face may mimic lupus vulgaris, chronic discoid erythematosus, cutaneous lymphoma and erysipelas.Citation10,Citation11 Infections by Leishmania are increasing worldwide due to tourism and job related travel and refugees.Citation12

The parasite multiplies inside the macrophages and other types of reticuloendothelial cells will rupture and release the organism into the blood stream. If the female sandfly bites an infected host, the amastigotes enter the sandfly and develop into infective promastigotes. This cycle is completed when the vector bites another host.

Common techniques used for diagnosis of leishmaniasis including CL and VL are (i) demonstration of parasites in tissues by light microscopic examination of stained specimen, in vitro or in vivo; (ii) immunodiagnosis by detection of parasite antigen in tissue, blood or urine samples by detection of antileishmanial antibodies or by assay for Leishmania-specific cell-mediated immunity or (iii) detection of parasites DNA in tissue samples.Citation13

Patients presenting with non-healing papular lesions need smear from the depth of the lesions after that staining with Giemsa or hematoxylin–eosin and identification of the parasite or Donovan bodies via light microscope.

CL lesion may heal spontaneously, with scarring or evolving into diffuse pattern of CL, with decreased immune response.Citation14 CL usually presents with painless nodules with a characteristic erythematous raised border similar to pimples. The lesions healed over months to years leaving with a scar. The causative species of CL decides the clinical presentation, course and treatment. Intralesional or systemic antimonials are the gold standard for the treatment.

After correct diagnosis of CL, the choice drug for treatment is important aspect as commonly used anti-leishmanial drugs such as antimony medications are often not enough as single therapy. It may cause a prolonged course of disease and give rise to undesirable side effects of antimony drugs and may be associated with disfiguring cutaneous scars. Confirmed CL diagnosis the combination regime should be used as first-line therapy to prevent prolonged exposure to single antimony therapy which may cause non-healing and resistant cases of CL. The combination therapy using recommended doses of allopurinol and antimony drugs shortens the duration of treatment. Combination therapy has been used successfully in resistant cases of VL.Citation15 Local treatment is carried out instead of systemic treatment if there is no risk for mucocutaneous leishmaniasis. Local treatment may be useful as an adjuvant to systemic treatment for accelerating the healing process. Topical ointment containing 15% paromomycin and 12% methylbenzethonium chloride was applied twice daily for 20 days. Paromomycin ointments are helpful in L. major, L. tropica, L. mexicana and L. panamensis. In case of L. braziliensis localized type of lesion, both paromomycin and imiquimod may be locally applied. Oral zinc sulphate and fluconazole are useful in L. major. Intramuscular pentamidine is required for L. guyanen CL, for which systemic antimony is not effective.Citation16

After developing Pentavalent antimonials, it remains first-choice treatment for both visceral and cutaneous leishmaniasis in most parts of the world. The Amphotericin B and pentamidine are the second-line antileishmanial drugs, although they require long courses of parenteral administration.Citation17 Basing upon the causative of leishmania species the choice of treatment is decided by the clinicians.Citation7 Although spontaneous cure is the rule, the rate of recovery varies depending on the species of causative agents, and may require months or years to complete healing.Citation18

Imidazoles are potential therapeutic agents in cutaneous leishmaniasis. They act by interfering with the synthesis of ergosterol that is present in the cell wall of Leishmania spp. The efficacy of ketoconazole in different doses for variable periods in cutaneous leishmaniasis has been documented.Citation19 Most of the commonly used drugs are toxic and do not cure, i.e., eliminate the parasite, from infected individuals. Failure to treat leishmaniasis successfully is often due to increased chemo-resistance of the parasite. Recently, microspheres of hydrophilic albumin with three amphotericin B aggregation states (monomeric, dimeric, and multiaggregate) and a ultiaggregate form encapsulated with two commercial polymers were tested against Leishmania infantum (both extracellular promastigote and intracellular amastigote forms). The albumin-encapsulated forms showed no toxicity. These amphotericin B encapsulated in microspheres are exploring new chemotherapeutic approaches.Citation20

4 Conclusion

Leishmaniasis is an infection caused by the protozoa Leishmania, transmitted by the sandfly. An isolated lesion over the face may form at the site of insect bite. These lesions are many times mistaken for leprosy, fungal dermatitis or facial pimples. Smears and histopathological examination should be done early for any lesion presenting more than two weeks under local anaesthesia and sent for examination to ensure the diagnosis and treatment.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that there is no conflict of interest.

Notes

Peer review under responsibility of Alexandria University Faculty of Medicine.

Available online 8 January 2016

References

- S.SinghNew development in the diagnosis of leishmaniasisIndian J Med Res1232006311330

- A.EjazN.RazaN.IftikharRecurrent cutaneous leishmaniasis presenting as sporotrichoid abscesses: a rare presentation near Afghanistan borderDermatol Online J13200715

- World Health Report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. p. 186–91.

- WHO Geneva. Control of the leishmaniasis. WHO Technical Report Series, vol. 793; 1990. p. 66–94.

- K.MuhammedK.NarayaniK.P.AravindanIndigenous cutaneous leishmaniasisIndian J Dermatol Venereal Leprol561990228229

- V.RastogiP.S.NirwanCutaneous leishmaniasis – an emerging infection in a non-endemic areas and a brief updateIndian J Med Microbiol252007272275

- J.ArevaloL.RamirezV.AdauiM.ZimicG.TullianoC.Miranda-VerásteguiInfluence of Leishmania (Viannia) species on the response to antimonial treatment in patients with American tegumentary leishmaniasisJ Infect Dis195200718461851

- B.L.HerwaldtLeishmaniasisLancet354199911911199

- P.DesjeuxThe increase in risk factors for leishmaniasis worldwideTrans R Soc Trop Med Hyg952001239243

- O.E.AkilovA.KhachemouneT.HasanClinical manifestations and classification of Old World cutaneous leishmaniasisInt J Dermatol462007132142

- A.BariS.B.RahmanMany faces of cutaneous leishmaniasisIndian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol7420082327

- S.E.VonC.SunderkötterCutaneous leishmaniasisHautarzt582007445458

- P.SalotraR.SinghChallanges in the diagnosis of post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasisIndian J Med Res1232006295310

- J.MishraA.SaxenaS.SinghChemotherapy of leishmaniasis: past, present and futureCurr Med Chem14200711531169

- G.KirigiM.W.MbuchiJ.K.MbuiJ.R.RashidD.M.KinotiS.N.NjorogeA successful treatment of a Kenyan case of unresponsive cutaneous leishmaniasis with a combination of pentostam and oral allopurinol: case reportEast Africal Med J872010521524

- G.WortmannL.P.HochbergB.A.AranaN.R.RizzoF.AranaJ.R.RyanDiagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Guatemala using a real-time polymerase chain reaction assay and the SmartcyclerAm J Trop Med Hyg762007906908

- V.S.AmatoF.F.TuonH.A.BachaV.A.NetoA.C.NicodemoMucosal leishmaniasis. Current scenario and prospects for treatmentActa Trop105200819

- R.ReithingerJ.C.DujardinH.LouzirC.PirmezB.AlexanderS.BrookerCutaneous leishmaniasisLancet Infect Dis72007581596

- M.KumaresanPramod.KumarLocalized cutaneous leishmaniasis in South India: successful treatment with ketoconazoleIndian J Dermatol, Venereol, Leprol7352007361

- L.Ordóñez-Gutié rrezR.Espada-FernándezM.A.Dea-AyuelaJ.J.TorradoF.Bolás-FernandezJ.M.AlundaIn vitro effect of new formulations of amphotericin B on amastigote and promastigote forms of Leishmania infantumInt J Antimicrob Agents302007325329