Abstract

Background and aim

Group B Streptococcus (GBS) has emerged as a leading cause of illness and death among neonates. The study was conducted to estimate the prevalence of recto-vaginal carriage of GBS among pregnant women at 35–37 weeks, gestation, to describe GBS antimicrobial susceptibility profile and to investigate selected virulence genes by PCR.

Subjects and methods

Two-hundred pregnant women at 35–37 weeks of gestation attending antenatal clinic at Al-Shatby University Hospital were enrolled in the study. Both vaginal and rectal swabs were collected from each subject. Swabs were inoculated onto CHROMagar™ StrepB and sheep blood agar plates. All GBS isolates were subjected to antimicrobial susceptibility testing using disc diffusion. Disc approximation test was performed to detect erythromycin resistance phenotype (MLSB). GBS virulence genes scpB, bac, bca, and rib were identified by PCR.

Results

Among the 200 pregnant women, 53 (26.5%) were identified as GBS carriers. All carriers had vaginal colonization (100%), four (7.5%) had combined recto-vaginal colonization. None of the carriers had rectal colonization alone. All isolates (100%) were susceptible to penicillin, ampicillin, ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, cefepime, vancomycin, and linezolid. On the other hand, 43.4%, 28.3%, 22.6%, and 15% of isolates were resistant to levofloxacin, azithromycin, erythromycin, and clindamycin respectively. Out of 12 erythromycin resistant isolates, six isolates had constitutive while two had inducible MLSB resistance. scpB was identified in 100%, rib in 79.2%, and bac in 35.8% of GBS isolates. None of the isolates possessed the bca gene.

Conclusion

Introduction of GBS screening in Egyptian pregnant women is recommended. Penicillin or ampicillin is still the antibiotic of choice for intrapartum prophylaxis.

1 Introduction

Streptococcus agalactiae (group B streptococcus; GBS) is one of the leading causes of neonatal sepsis and meningitis. GBS neonatal disease is classified as either early-onset disease (<7 days) or late-onset disease (>7–90 days). Early-onset GBS disease (EOD) is mainly caused by vertical transmission of GBS from colonized mothers to their infants during labor or delivery. Approximately 10–40% of pregnant women are colonized with GBS, and the incidence of EOD is 0.3–2 per 1000 live births in different geographical areas.Citation1

GBS is also associated with preterm labor or membrane rupture, as well as urinary tract infections, postpartum endometritis, postpartum wound infection, septic pelvic thrombophlebitis and endocarditis in females.Citation2

In 1996, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published consensus guidelines for the prevention of neonatal GBS disease; these guidelines were revised in 2002 then in 2010.Citation1The revised guidelines recommended the screening of all pregnant women between 35 and 37 weeks of gestation for vaginal and rectal colonization with GBS. Further, the guidelines recommended intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP) for colonized pregnant women.

It has been shown that the screening approach and IAP rather than the identification of maternal clinical risk factors for early-onset neonatal GBS disease are more effective in preventing EOD.Citation3In developed countries prenatal screening in pregnant women and IAP have been widely established and successfully reduced the incidence of GBS neonatal disease.Citation1,Citation4In low-income settings screening and IAP for prevention of invasive neonatal disease are mostly not implemented due to limitations in resources and infrastructure.Citation5

GBS remain fully susceptible to penicillin as well as to most β-lactams.Citation6–Citation9 However, there are some worrisome reports on reduced penicillin susceptibility in GBS.Citation10,Citation11On the other hand, alternative antibiotics are administrated for pregnant women with penicillin allergy, such as clindamycin, erythromycin, or vancomycin.Citation1 Increased resistance rates to clindamycin and to erythromycin were reported in different parts of the world including reports from Egypt.Citation9,Citation12–Citation16

The severity of neonatal disease in GBS infections could be determined mostly by a number of virulence factors encoded. The capsular polysaccharides have been identified as a major virulence factor. Other factors thought to be associated with virulence include the surface-associated C proteins, α and β, encoded by the bca and bac genes, respectively, which participate in adherence, invasion of cervical epithelial cells, as well as resistance to phagocytosis, and the Rib protein encoded by the rib gene which has been found in significant percentage of GBS strains which caused invasive infections in neonates.Citation17–Citation19These putative virulence factors have been investigated as possible vaccine candidates because of their ability to elicit protective immunity against GBS infections.Citation20,Citation21

In Egypt, there is no national guideline for systematic screening or prophylaxis of GBS in pregnant women. This was the motivation for conducting this study. The objective of the study was to determine the prevalence of GBS carriage among pregnant women at 35–37 weeks of gestation, to evaluate the antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of colonizing GBS isolates, and to investigate selected GBS virulence genes.

2 Subjects and methods

This cross-sectional observational study included 200 pregnant women at 35–37 weeks of gestation attending antenatal clinic at Al-Shatby University Maternity Hospital, Alexandria, Egypt. From all study subjects two swabs, one rectal and one vaginal were collected. For rectal specimens, a swab was carefully inserted approximately 2.5 cm beyond the anal sphincter and then gently rotated to touch anal crypts. For vaginal specimens, excessive secretions or discharge were wiped away, and a swab was taken from the mucosa of the lower third of the vagina without using a speculum as per CDC recommendations.Citation1

Exclusion criteria:

| – | Pregnant women who were on antibiotic treatment 2 weeks prior to recruitment. | ||||

| – | History of complicated previous or current pregnancy (abortion, premature rupture of membranes, premature delivery). | ||||

| – | Women with urinary tract infection or vaginal infection in the current pregnancy. | ||||

The study was approved by the research ethics committee of Alexandria University Hospital.

2.1 Demographic data collection

Demographic data was recorded, including the patient’s age, gestational age, number of pervious pregnancies, number of antenatal visits, contraceptive method used.

2.2 Specimen collection and transport

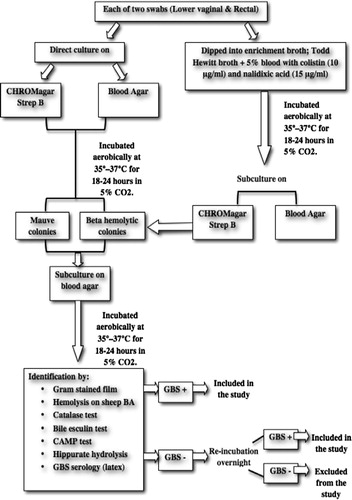

| – | Each swab (vaginal or rectal) was inoculated directly onto each of chromogenic agar plate; CHROMagar™ StrepB (CHROMagar microbiology, France) and sheep blood agar plates (Oxoid, UK), just after sample collection.Citation22Then swabs were dipped into 5 ml of selective enrichment broth; Lim Broth (Todd Hewitt, Oxoid, supplemented with 5% sheep blood with colistin (10 μg/ml) and nalidixic acid (15 μg/ml). | ||||

The inoculated plates and broths were transported immediately in ambient temperature to the Microbiology Laboratory of Alexandria Main University Hospital (AMUH) to be processed according to the recommendations of CDC.Citation1

2.3 Specimen processing

| – | The inoculated CHROMagar™ StrepB and blood agar plates were incubated aerobically at 35–37 °C for 18–24 h in 5% CO2. | ||||

| – | The inoculated selective broth was incubated for 18–24 h at 35–37 °C in 5% CO2, then was subcultured onto CHROMagar™ StrepB, and sheep blood agar and incubated aerobically at 35–37 °C for another18–24 h in 5% CO2. | ||||

| – | After incubation period, plates were examined. The suspected GBS colonies on CHROMagar™ StrepB (mauve colonies) and on blood agar (b-haemolytic and non-haemolytic) were picked and subcultured onto sheep blood agar and incubated aerobically at 35–37 °C for 18–24 h in 5% CO2. Isolates were identified using conventional methods on the basis of colonial morphology, Gram staining, haemolysis, CAMP test, bile esculin, hippurate hydrolysis (Liofilchem, Italy), and latex agglutination test with specific antisera (Strepto B latex kit, Liofilchem, Italy).Citation23 (). | ||||

| – | The isolated identified strains were stored in Todd- Hewitt broth along with 15% glycerol at −70 °C until tested. The negative culture results were issued at 72 h, according to the CDC recommendations. | ||||

2.4 Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

| – | The susceptibilities of GBS isolates to different antimicrobial agents were tested using modified Kirby Bauer disc diffusion method. The following antimicrobial discs and concentrations were selected according to CLSI guidelines: Penicillin (P), 10 units; ampicillin (AMP), 10 μg; ceftriaxone (CRO), 30 μg; cefotaxime (CTX), 30 μg; cefepime (FEP), 30 μg; erythromycin (E), 15 μg; azithromycin (AZM), 15 μg; clindamycin (DA), 2 μg; tetracycline (TC), 30 μg; vancomycin (VA), 30ug; linezolid (LZD), 30ug; levofloxacin (LEV), 5 μg (Oxoid). Streptococcus pneumoniae ATCC 49619 was used as quality control strain as recommended by the CLSI.Citation24 | ||||

| – | Erythromycin-resistant isolates were further classified as having cMLSB (constitutive macrolide—lincosamide—StreptograminB resistance), iMLSB (inducible resistance), or M phenotype (macrolide—StreptograminB resistance and Lincosamide susceptibility) by double-disc approximation method. Blunting was defined as growth within the clindamycin zone of inhibition proximal to the erythromycin disc, indicating MLSB inducible methylation. Resistance to both erythromycin and clindamycin indicated MLSB-constitutive methylation. Resistance to erythromycin but susceptibility to clindamycin without blunting indicated an efflux mechanism (M phenotype).Citation25 | ||||

2.5 Molecular test (PCR)

DNA extraction from bacteria was performed by the method described by Schmitz et al.Citation26The supernatant (three uL) was used as a template in the PCR reaction. Four separate PCR reactions were done. Each PCR reaction consisted of 12.5 μL MyTaq Red Mix, 2× (Bioline, UK), 25 pmol of primers, and PCR grade water to a final volume 25 μl. The sets of primers (Invitrogen by Life Technologies, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., USA) for the detection of genes encoding immunoglobulin A-binding β-antigen (bac), α-antigen (bca), C5a peptidase (scpB), and rib are listed in .

Table 1 Primer sequences used in the study.

The conditions of the amplification reaction were: an initial denaturation step at 95 °C for 2 min, 35 amplification cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 55 °C for 60 s, extension at 72 °C for 60 s, followed by a final cycle of extension at 72 °C for 10 min. Negative extraction and master mix controls were included in every reaction.Citation27,Citation28

2.6 Statistical analysis of the data

Data were fed to the computer and analyzed using IBM SPSS software package version 20.0. Qualitative data were described using number and percent. Quantitative data were described using mean, standard deviation. Significance of the obtained results was judged at the 5% level.

3 Results

3.1 Prevalence

| – | Among the 200 pregnant asymptomatic women at 35–37 weeks of gestation, 53 (26.5%) were identified as GBS carriers. Vaginal colonization was shown in all carriers (53; 100%). Out of the 53 vaginal carriers, four (7.5%) had combined recto-vaginal colonization. None of the carriers had rectal colonization only. | ||||

3.2 Demographic data results

| – | The mean age of pregnant women carriers for GBS was (25.4 ± 2.9). GBS colonization was common mostly in the age group (20–30) and this finding was statistically significant (p = 0.01). GBS colonization was statistically significantly higher at 37 weeks of gestation (p = 0.002), among women who had frequent antenatal visits (p=<0.001), and who adopted the condom contraceptive method (p=<0.001). On the hand, the prevalence of GBS colonization was high among the multigravida but this was not statistically significant (p = 0.296). The results of socio-demographic characteristics are summarized in . | ||||

Table 2 The socio-demographic factors associated with GBS colonization in the 200 pregnant women.

3.3 Culture results

| – | Detection of GBS from vaginal and rectal specimens by direct plating onto CHROMagar strepB or blood agar was equally sensitive as detection after selective broth enrichment. The turn-around time was 18–24 h when using the direct plating, versus 48 h after selective broth enrichment. On CHROMagar strept B; all mauve colonies were confirmed to be GBS isolates. On the other hand, not all beta hemolytic colonies or small non-hemolytic catalase negative colonies proved to be GBS on sheep blood agar where it required more effort for picking and isolation of GBS colonies. | ||||

3.4 Antibiotic susceptibility results

| – | None of the isolates was resistant to penicillins such as penicillin and ampicillin. Furthermore, all isolates were susceptible to ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, cefepime, vancomycin, and linezolid. On the other hand, 23 (43.4%), 15 (28.3%), 12 (22.6%), and 8 (15%) isolates were resistant to levofloxacin, azithromycin, erythromycin, and clindamycin respectively. Eleven isolates (20.8%) of GBS were intermediately sensitive to tetracycline (). | ||||

| – | Concerning double disc approximation test for detection of erythromycin resistance phenotype, cMLSB mechanism was found in 50% (6/12) of erythromycin resistant isolates, while, iMLSB resistance was detected in two isolates (2/12; 16.7%). M phenotype was reported in four isolates (4/12; 33.3%). | ||||

3.5 PCR results

| – | All isolates possessed scpB gene (100%). The presence of rib gene was confirmed in 42 isolates (79.2%), bac in 19 isolates (35.8%). ScpB, rib and bac were identified in 19 isolates (35.8%). Twenty-three isolates (43.4%) were scpB, rib positive and bac negative. None of the isolates possessed the bca gene. A significant proportion (23 isolates; 43.3%) had the scpB, and rib genes simultaneously. The presence of these two genes characterized the prevalent virulence profile among our isolates. Nineteen isolates (35.8%) contained three virulence genes (scpB, rib, bac), while 11 isolates (20.7%) were positive only for a single gene (scpB gene) (, ). | ||||

Fig. 3 Agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR of GBS virulence genes. Lane 8 = DNA ladder. Lane 1, 2, 11 = Negative samples. Lane 3, 4, 9, 10 = scpB positive isolates (255 bp). Lane 5, 6, 7, 13 = rib positive isolates (369 bp), Lane 12 = bac positive isolate (530 bp). Lane 14, 15 = Negative controls.

Table 3 The frequency of virulence genes (scpB, bac, bca and rib) among GBS isolates.

The virulence genes scpB & rib were detected in 15/15 (100%) and 4/15 (26.7%) of azithromycin-resistant isolates, respectively, in 12/12 (100%), and 4/12 (33.3%) of the erythromycin-resistant GBS isolates, respectively, and in 8/8 (100%), and 4/8 (50%) of the clindamycin- resistant isolates, respectively. While, the scpB, rib, and bac genes were identified in 23/23 (100%), 11/23 (47.8%), 8/23 (34.8%) of the levofloxacin resistant isolates. The bac gene was not detected in any of the erythromycin, azithromycin or clindamycin resistant isolates ().

Table 4 The distribution of GBS isolates resistant to each antibiotic according to virulence genes.

4 Discussion

In the present study, the rate of GBS among pregnant women was 26.5%, which is in agreement with other Egyptian studiesCitation13,Citation29 and higher than the rates reported in others.Citation30,Citation31According to a review article published in 2010, which consists of 76 original articles, the results demonstrated that Middle East are accounted for high risk countries for GBS colonization.Citation32This worldwide variability is related to different sociocultural, geographic, climatic, biological and methodological determinants and this highlights the importance of individualizing preventive strategies according to local colonization rates.

Our results demonstrated that most GBS positive pregnant women were from 20 to 30 years old which is in accordance with previous studies conducted in Africa.Citation33,Citation34On the contrary, other studies reported increase in GBS positivity as the age increases.Citation10,Citation35The results of the current study found that GBS colonization is significantly higher among pregnant women who are at 37th week of gestation, who had frequent antenatal visits, and who use the condom as a contraception method. Our findings are not in agreement with those from other studiesCitation33,Citation36,Citation37 that reported no significant differences in the GBS colonization rates when the sociodemographic and clinical obstetric variables including the risk factors for the newborn to develop infection were considered.

Taking into consideration that we did not take combined vagino-rectal swabs using the same swab, we can assume that combined vagino-rectal swabs would have been positive with all positive GBS cases in this study and that only vaginal swab is enough for screening of GBS. Our results are not in accordance with CDC recommendations to carry out rectovaginal sampling for GBS screening and are also different from many other studies that found rectovaginal sampling more appropriate than vaginal sampling only.Citation1,Citation38However, it should be mentioned that Nomura et al.Citation39found no significant difference in detection rates between vaginal and rectal samples. Votava et al.Citation40even found that the GBS detection rate using rectovaginal samples was only 16.9%, whereas the use of separate vaginal and rectal swabs yielded 22.7 and 24.1% GBS positive women, respectively. Gupta & BriskiCitation41reported that although rectovaginal swabs are reported to increase the yield of GBS, this finding was not supported by their study. Also, several obstetric departments still use vaginal sampling only to assess GBS carriage.Citation38The low count and often weakly hemolytic colonies of GBS within the large diverse population of rectal flora may explain the negative rectal samples in our study.

In the present study, the sensitivity of direct plating was comparable to that after selective TH broth enrichment. Similarly, El Aila et al.Citation38reported comparable sensitivity of direct plating on chromID™ Strepto B agar (CA) and group B streptococcus differential agar (GBSDA) to that of plating on CA and GBSDA after Lim broth enrichment, whereby the latter enabled the detection of only one additional sample.

Although blood agar remains the agreed common reference for GBS culture, our results differed from the previous studiesCitation42,Citation43as CHROMagar™ StrepB showed a similar performance as blood agar, however, the effort done to isolate suspected GBS colonies from blood agar was much bigger. The CHROMagar strepB allowed direct visual inspection of GBS colonies within 24 h. Moreover, the selection and picking of colonies was much easier (mauve colonies). It also supported growth of all GBS strains and produced typical colonies whatever their haemolytic properties in an aerobic environment.

Using the disc diffusion test, all tested isolates in this study were susceptible to penicillins and ampicillin, indicating that they would be effective as the first-line agents for IAP in our settings. No resistance was also reported for cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, cefepime, vancomycin and linezolid. Similar findings have been reported for GBS strains around the world including reports from Egypt.Citation6–Citation9,Citation13 On the other hand, the very high level of penicillin and ampicillin resistance (100%) was alarming when reported in Nigeria.Citation10The authors justified this high rate by the ease of procurement of antibiotics in the developing country, the frequent use of antibiotics for therapy and prophylaxis, and other socio-economic factors.

Conversely, some women with penicillin allergy require other antibiotics for GBS prophylaxis such as clindamycin, erythromycin, or vancomycin, which are recommended in the CDC guidelines.Citation1All isolates in the present study were susceptible to vancomycin. However, 22.6% and 15% of the tested isolates were resistant to erythromycin and clindamycin, respectively. Thus susceptibility testing should be performed before administering erythromycin or clindamycin in order to ensure activity against the isolate. Our results are slightly different from another study conducted in Egypt, which reported 13.15% resistance to erythromycin and 23.68% to clindamycin.Citation13Resistance has been reported between 4 to 58.3% and 2.3% to 57.9% for erythromycin and clindamycin respectively in published literatures.Citation9,Citation12–Citation16 Consequently, the revised CDC guidelines in 2010Citation1excluded erythromycin from the recommended alternative antibiotics.

In our study, cMLSB erythromycin resistant phenotype was found in six isolates (50%) of the 12 erythromycin non-susceptible isolates. While, 16.7% (2/12) of isolates showed iMLSB phenotype. Our results are in agreement with studies from Egypt, Portugal, and FranceCitation13,Citation44,Citation45, which reported that the majority of the erythromycin-resistant isolates showed cMLSB resistance. Therefore, in GBS isolates that are not susceptible to erythromycin, resistance to clindamycin should be suspected in about 2/3 of cases. The resistance of 66.7% (8 strains) of GBS strains to both antibiotics makes their use impractical as prophylactic antibiotic for pregnant GBS carriers in our hospitals. The M phenotype was detected in 33.3% (4/12) in the present study, but its occurrence has been reported among human GBS isolates at low rates.Citation28

Some authors suggest that the presence of the scpB gene in human isolates is mandatory.Citation46,Citation47Others detected scpB in 97% of human isolatesCitation28, but generally it is thought that only strains possessing scpB gene are infective for humans.Citation18The scpB gene was detected in all isolates in the current study.

In the present study, bac gene was detected in 17 isolates (35.8%), It is generally a low rate when compared to a previous study.Citation18 On the other hand, Corrêa et al.Citation48 and Durate et al.Citation28 reported that none of their GBS carried the bac gene. Concerning the rib gene, it was unexpectedly detected in a very high percentage of our isolates; 42 isolates representing 79.2%. This was not consistent with a previous study conducted in Egypt which reported a rate of only 13%,Citation29 also in the study of Monica et al.Citation18, the rib gene was found in 35% of isolates. Previous studies noted that bca and rib genes were not present concomitantly in the same genome.Citation49,Citation50 Rib protein encoded by the rib gene shares several properties with α-C protein encoded by bca gene. Both proteins are resistant to trypsin digestion and belong to the same family of bacterial surface proteins with repetitive structures showing a 47% identity, their N- terminal sequences are related and are 61% identical to each other. These properties suggest that both proteins may have a common origin.Citation51 This observation may explain the negative bca gene results in the present study. In addition, the detection of rib and bac genes in 79.2, 35.8%, respectively, of the isolates in this study suggests that a GBS vaccine containing these proteins would be less effective against Egyptian population.

All azithromycin, erythromycin, clindamycin and levofloxacin resistant GBS isolates in this study (100%) carried the scpB gene. While none of the azithromycin, erythromycin and clindamycin resistant isolates carried the bac gene. This finding could be of help when designing the vaccine.

The most important limitation of our study was the inability to follow up the positive GBS culture pregnant women to determine the rate of premature rupture of membranes and infantile infection. Another limitation is that serotyping of GBS was not done because of lack of antisera due to financial constraints. Knowledge about the prevalent serotypes in a given country is very important in development and implementation of effective vaccine.

5 Conclusion

The establishment of carriage status in pregnant women for GBS calls for a review of the present hospital policy to include routine screening and reporting of GBS colonization among pregnant women during antenatal visits. Rectal swab does not confer a clear benefit; so vaginal swab is enough for screening. Penicillin or ampicillin is still the antibiotic of choice for IAP. However, erythromycin or clindamycin susceptibility testing is still mandatory in case of penicillin allergy.

While the knowledge of the most prevalent virulence factors of GBS isolates from a given geographical area is essential to trace the epidemiological course of infections, surveillance of antimicrobial-resistance is relevant to guiding the design of more appropriate procedures for infection control and prevention. Moreover, further studies should be conducted to identify the most prevalent serotypes among Egyptian GBS isolates to guide in the design of appropriate vaccine.

6 Conflicts of interest

None.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Notes

Peer review under responsibility of Alexandria University Faculty of Medicine.

Available online 21 February 2017

References

- Centers for Disease Control and PreventionPrevention of perinatal group B streptococcal diseaseMorb Mortal Wkly Rep1920101e36

- Murray PR, Rosenthal KS, Pfaller MA. Medical microbiology. 5th ed. USA; 2005: 247–50.

- S.SchragD.PhilE.R.ZellM.StatR.LynfieldA.RoomeA population based comparison of strategies to prevent early-onset group B streptococcal disease in neonatesN Engl J Med3472002233239

- S.J.B.LopezC.B.FernandezC.G.D.CotoA.A.RamosTrends in the epidemiology of neonatal sepsis of vertical transmission in the era of group B streptococcal preventionActa Paediatr942005451

- M.CapanG.Mombo-NgomaD.Akerey-DiopEpidemiology and management of group B streptococcal colonization during pregnancy in AfricaWien Klin Wochenschr124201214

- S.M.GarlandE.CottrillL.MarkowskiAntimicrobial resistance in group B streptococcus: the Australian experienceJ Med Microbiol602011230235

- A.DhanoaR.KarunakaranS.D.PuthuchearySerotype distribution and antibiotic susceptibility of group B streptococci in pregnant womenEpidemiol Infect1382010979981

- S.Y.MurayamaC.SekiH.SakataCapsular type and antibiotic resistance in Streptococcus agalactiae isolates from patients, ranging from newborns to the elderly, with invasive infectionsAntimicrob Agents Chemother53200926502653

- A.A.AllamM.A.BahgatPhenotype and genotype of some clinical Group B streptococcus isolates resistant to erythromycin in EgyptEgypt J Med Microbiol1520067177

- A.OnipedeO.AdefusiA.AdeyemiE.AdejuyigbeA.OyeleseT.OgunniyiGroup B Streptococcus carriage during late pregnancy in Ile-Ife, NigeriaAfr J Clin Exp Microbiol132012135143

- K.KoujiN.NoriyukiN.YukikoPredominance of sequence type 1 group with serotype VI among group B streptococci with reduced penicillin susceptibilityJ Antimicrob Chemother6611201124602464

- S.ShabayekS.AbdallaMacrolide- and tetracycline-resistance determinants of colonizing group B streptococcus in women in EgyptJ Med Microbiol63201413241327

- S.A.ShabayekS.M.AbdallaA.M.AbouzeidVaginal carriage and antibiotic susceptibility profile of group B Streptococcus during late pregnancy in IsmailiaEgypt J Infect Public Health2220098690

- T.AbdelmoatyZ.WafaaM.KawtharPrevalence and antibiotic susceptibility of anogenital group B streptococci colonization in pregnant womenEgypt J Med Lab1822009105111

- A.JoachimM.I.MateeF.A.MassaweE.F.LyamuyaMaternal and neonatal colonization of group B Streptococcus at Muhimbili national hospital in Dares Salaam, Tanzania: prevalence, risk factors and antimicrobial resistanceBMC Public Health92009437

- M.QuirogaE.PegelsP.OviedoE.PereyraM.VergaraAntibiotic susceptibility patterns and prevalence of Group B Streptococcus isolated from pregnant women in Misiones, ArgentinaBraz J Microbiol392008245250

- N.DoreD.BennettiM.KaliszerM.CafferkeyC.J.SmythMolecular epidemiology of group B streptococci in Ireland: associations between serotype, invasive status and presence of genes encoding putative virulence factorsEpidemiol Infect1312003823833

- M.E.LysakowskaJ.KalinkaM.BigosM.ProsniewskaM.WasielaOccurrence of virulence genes among S. agalactiae isolates from vagina and anus of pregnant women – a pilot studyArch Perin Med172011229234

- M.J.BaronD.J.FilmanG.A.PropheteIdentification of a glycosaminoglycan binding region of the alpha C protein that mediates entry of group B streptococci into host cellsJ Biol Chem28220071052610536

- H.J.JenningsCapsular polysaccharides as vaccine candidatesCurr Top Microbiol Immunol150199097127

- D.MaioneI.MargaritC.D.RinaudoIdentification of a universal Group B streptococcus vaccine by multiple genome screenScience3092005148150

- H.BlanckaertJ.FransJ.BosteelsM.HanssensJ.VerhaegenOptimisation of prenatal group B streptococcal screeningEur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis222003619621

- P.M.TilleBailey & Scott’s Diagnostic Microbiology13th ed.2013Mosby ElsevierPhiladelphia, PA, USA

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Twenty-fifth Informational Supplement. CLSI Document M100-S25, vol. 35. Wayne, Pennsylvania, USA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2015: 3.

- M.DesjardinsK.L.DelgatyK.RamotarC.SeetaramB.ToyePrevalence and mechanisms of erythromycin resistance in group A and group B Streptococcus: implications for reporting susceptibility resultsJ Clin Microbiol42200456205623

- F.J.SchmitzM.SteiertH.V.TichyB.HofmannG.VerhoefTyping of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from Dusseldorf by six genotypic methodsJ Med Microbiol471998341351

- S.D.ManningM.KiC.F.MarrsThe frequency of genes encoding three putative group B streptococcal virulence factors among invasive and colonizing isolatesBMC Infect Dis62006116

- R.S.DuarteB.C.BelleiO.P.MirandaM.A.BritoL.M.TeixeiraDistribution of antimicrobial resistance and virulence-related genes among Brazilian group B streptococci recovered from bovine and human sourcesAntimicrob Agents Chemother49200597103

- S.ShabayekS.AbdallaA.M.AbouzeidSerotype and surface protein gene distribution of colonizing group B streptococcus in women in EgyptEpidemiol Infect1422014208210

- I.E.WaliA.E.SorourM.A.H.AbdallaAssessment of different methods for detection of Group B Streptococci carriage among pregnant femalesEgypt J Med Microbiol162007593598

- S.M.Y.ElbaradieM.MahmoudM.FaridMaternal and neonatal screening for Group B streptococci by SCP B gene based PCR: a preliminary studyInd J Med Microbiol2720091721

- A.W.Valkenburg-van den BergR.L.Houtman- RoelofsenP.M.OostvogelF.W.DekkerP.J.DörrA.J.SprijTiming of group B streptococcus screening in pregnancy: a systematic reviewGynecol Obstet Invest692010174183

- M.MohammedD.AsratY.WoldeamanuelA.DemissiePrevalence of group B Streptococcus colonization among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic of Hawassa Health Center, Hawassa, EthiopiaEthiop J Health Dev2620123642

- R.T.MavenyengwaJ.E.AfsetB.ScheiGroup B Streptococcus colonization during pregnancy and maternal-fetal transmission in ZimbabweActa Obstet Gynecol Scand892010250255

- O.Donbraye-EmmanuelI.OkonkoE.DonbrayeIsolation and characterization of Group B Streptococci and other pathogens among pregnant women in Ibadan, Southwestern NigeriaJ Appl Biosci5902201017811792

- D.S.Castellano-FilhoV.L.da SilvaT.C.NascimentoVieira M.de ToledoC.G.DinizDetection of Group B Streptococcus in Brazilian pregnant women and antimicrobial susceptibility patternsBraz J Microbiol41201010471055

- N.JonesK.OliverY.JonesA.HainesD.CrookCarriage of group B streptococcus in pregnant women from Oxford, UKJ Clin Pathol592006363366

- N.A.El AilaI.TencyG.ClaeysComparison of different sampling techniques and of different culture methods for detection of group B streptococcus carriage in pregnant womenBMC Infect Dis102010285

- M.L.NomuraR.Passini JuniorU.M.OliveiraSelective versus non-selective culture medium for group B streptococcus detection in pregnancies complicated by preterm labor or preterm-premature rupture of membranesBraz J Infect Dis102006247250

- M.VotavaM.TejkalovaM.DrabkovaV.UnzeitigI.BravenyUse of GBS media for rapid detection of group B streptococci in vaginal and rectal swabs from women in laborEur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis202001120122

- C.GuptaL.E.BriskiComparison of two culture media and three sampling techniques for sensitive and rapid screening of vaginal colonization by group B streptococcus in pregnant womenJ Clin Microbiol42200439753977

- D.M.PoissonM.ChandemerleJ.GuinardM.L.EvrardD.NaydenovaL.MesnardEvaluation of CHROMagar StrepB: a new chromogenic agar medium for aerobic detection of Group B Streptococci in perinatal samplesJ Microbiol Meth822010238242

- Charron J, Demandion E, Laudat P. Détection rapide par culture de Streptococcus agalactiae dans les prélèvements génitaux sur un nouveau milieu chromogène CHROMagar StrepB. Poster 5508. Paris: Réunion Interdisciplinaire de Chimiothérapie Anti-Infectieuse; 2009.

- J.Figueira-CoelhoM.RamirezM.J.SalgadoJ.Melo-CristinoStreptococcus agalatiae in large Portuguese teaching hospital: antimicrobial susceptibility serotype distribution and clonal analysis of macrolide-resistant isolatesMicrob Drug Resist1020043136

- D.De MouyJ.-D.CavalloR.LeclercqR.FabreAntibiotic susceptibility and mechanisms of erythromycin resistance in clinical isolates of Streptococcus agalactiae: French multicenter studyAntimicrob Agents Chemother45200124002402

- C.FrankenG.HaaseC.BrandtHorizontal gene transfer and host specificity of beta-haemolytic streptococci: the role of a putative composite transposon containing scpB and lmbMol Microbiol412001925935

- A.DmitrievA.SuvorovA.D.ShenY.H.YangClinical diagnosis of group B streptococci by scpB gene based PCRIndian J Med Res1192004233236

- A.B.CorrêaI.C.OliveiraC.Pinto TdeM.C.MattosL.C.BenchetritPulsed-field gel electrophoresis, virulence determinants and antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of type Ia group B streptococci isolated from humans in BrazilMem Inst Oswaldo Cruz1042009599603

- A.HannounM.ShehabM.T.KhairallahCorrelation between group B streptococcal genotypes, their antimicrobial resistance profiles, and virulence genes among pregnant women in LebanonInt J Microbiol2009 2796512

- F.KongS.GowanD.MartinG.JamesG.L.GilbertMolecular profiles of group B streptococcal surface protein antigen genes: relationship to molecular serotypesJ Clin Microbiol402002620626

- M.WastfeltM.Stalhammar-CarlemalmA.M.DelisseT.CabezonG.LindahlIdentification of a family of streptococcal surface proteins with extremely repetitive structureJ Biol Chem27119961889218897