Abstract

Cryptosporidium infection is known worldwide as an important aetiology of chronic diarrhoea that can become fatal in children (below 5 years of age) and immunocompromised individuals. This review was aimed at identifying some traditional practices that may be risk factors for childhood diseases like cryptosporidiosis in a country like Nigeria with different tribes and cultures. Information gathered from literature search and informal sources identified some indigenous practices like birth rituals, special childhood menus, traditional nanny practice, local management of childhood diarrhoea and some myths among others, as factors that may negatively impact childhood health in a multi-cultural population like Nigeria. A proper understanding of these traditional practices will enable the prevention and control of childhood disease like cryptosporidiosis in a multi-ethnic setting.

1 Introduction

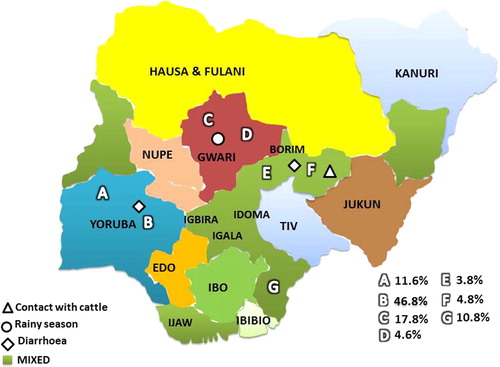

1.1 Nigeria

Nigeria with a population of about 152 million is the most populous country in West Africa.Citation1 The country has a land mass of 923,768 sq km and lies between Latitudes 4–14° North and between Longitudes 2°2′ and 14°30′.Citation2 Nigeria has a rich cultural diversity with over 250 different ethnic groups, all having their unique languages, customs and traditions. However, three main tribes Hausa, Igbo and Yoruba dominate the northern, southern, and western Nigeria respectivelyCitation3 (). Nigeria has a warm tropical climate with relatively high temperatures throughout the year. There is a rainy season (mid-March to November in the South and from May to October in the north) and dry season during the other months of the year.Citation4 Agriculture (crop production, animal husbandry, fishery and forestry) is the major occupation of the people in the rural areas of Nigeria.

1.2 Cryptosporidiosis

Cryptosporidium infection is known worldwide as an important aetiology of diarrhoea in both immunocompromised and immunocompetent individuals.Citation5,Citation6 In the developed and developing countries, cryptosporidiosis occurs more often in infants and children than in adults.Citation7,Citation8 The infection is transmitted to the susceptible host via the fecal-oral route from the consumption of food and water contaminated with oocyst from an infected host.Citation9 Other suggested sources of Infection include contact with infected humans, animals, and contaminated recreational waters.Citation10–Citation12 Cryptosporidiosis is characterised by a self-limited diarrheal illness in healthy individuals but may cause chronic diarrhoea that may be fatal to infants and individuals with compromised immune systems, such as persons with HIV/AIDS.Citation13 In children, cryptosporidiosis is mainly characterised by watery diarrhoea that can persist for up to 12 weeks and this condition is usually fatal in malnourished children.Citation14–Citation17

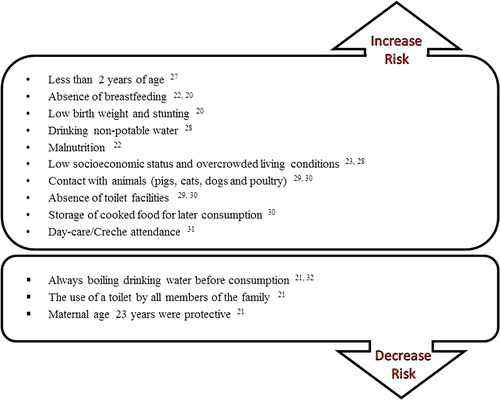

Several published reports are available on the epidemiology of Cryptosporidium infection in children and associated risk factors that might influence the pattern and outcome of the disease ( and ).

Fig. 2 Some risk factors suggested to be associated with childhood cryptosporidiosis. (See above-mentioned references for further information.).

Table 1 Data on childhood cryptosporidiosis from some other countries in different continent.

1.3 Childhood Cryptosporidium in Nigeria

There are few available studies on the prevalence of childhood (aged 0–5 years) Cryptosporidium infection in children. Three of these studies investigated the infection in both diarrhoeic and non-diarrhoeic childrenCitation33–Citation35, while the others studied the infection in only diarrhoeic childrenCitation36,Citation19,Citation37 and in malnourished children.Citation38 Methods employed by these studies include Modified Ziehl-Neelsen staining method; enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay technique (ELISA) and molecular methods (). Few available information on childhood cryptosporidiosis were reported for two states (Oyo and Osun) in south-western Nigeria,Citation33,Citation35 two state (Jos and Zaria) in Northern NigeriaCitation19,Citation34,Citation37 and only one state in South Eastern Nigeria.Citation36 The overview of these reports according to tribes is represented in .

Table 2 Cryptosporidiosis prevalence in children (0–5 years) in Nigeria.

The control of Cryptosporidiosis in multi-cultural population would require a more holistic approach that would not only depend on modern science but also harness indigenous knowledge for effective prevention and control of the disease. This paper, therefore, aims at reviewing different traditional practices that may impact the prevalence of childhood cryptosporidiosis in Nigeria. Information for this review was obtained through literature search on data bases that include PubMed, ISI, Google Scholar, Scopus and African journal online (AJOL) using key words like diarrhoea in Nigerian children, traditional practices in Nigeria, and cryptosporidiosis in Nigeria. We also gathered information from non-indexed articles from libraries and personal communications.

2 Traditional beliefs and practices that may negatively impact childhood health in Nigeria

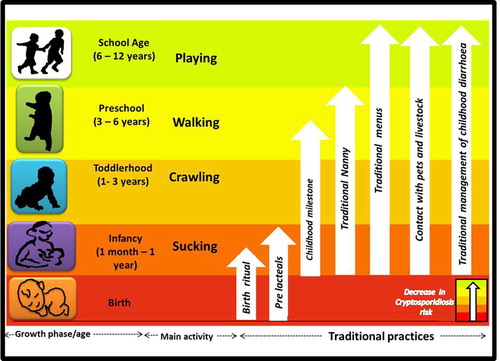

Traditional practices associated with cultural belief systems are very important to the care of the new born and children in countries with diverse tribes and cultures like Nigeria. The following practices may directly or indirectly be potential risk factors for childhood cryptosporidiosis in Nigeria. The probable relationship between identified traditional practices, growth phases of children and risk of cryptosporidiosis is summarized in .

Fig. 3 Coloured chart showing levels of susceptibility with age to Cryptosporidium infection in relation to identified traditional practices.

2.1 Breastfeeding and weaning practices

Breastfeeding is known to be one of the simplest, healthiest, least expensive and the oldest feeding practice that satisfies the infant’s needs.Citation39 As important as breastfeeding is, there is evidence to show that breastfeeding is deliberately delayed in some places in Southwestern and northern part of Nigeria due to the cultural belief that colostrum is dirty and harmful to the new born.Citation40 In such places, mothers expressed and throw away early milk (colostrum), and feed pre-lacteal such as animal milk, honey, boiled water and herbal preparation while waiting for the ‘appropriate time’ to initiate feeding with the “clean breast milk”. This practice may lead to low immunity that could make infant susceptible to cryptosporidiosis and other childhood diseases.

Traditional force-feeding is a popular practice among the Hausas and Yorubas of the Northern and Southwestern, Nigeria respectively.Citation41,Citation42 This is a practice where mothers (usually elderly women) feed their babies by force through oral drenching using bare hands in order to ensure that the children take in enough food for proper growth. The risk of using bare hands (which in most cases might not be properly washed) for feeding babies may enable the transmission of contaminative infection like Cryptosporidiosis from infected adult to infants’ children.

In some traditional settings, the idea of exclusive breastfeeding is considered unsafe for infants because it is believed that infants do get thirsty and require water to “quench” their thirst. In addition, the practice of complementary feeding is popular among some native that believed that ordinary fluid from the mammary gland may not be enough as a meal for an infant. These practices create an opportunity for the ingestion of food and water contaminated with Cryptosporidium oocysts shed from infected individuals. Non-compliance with the practice of exclusive breastfeeding could also increase susceptibility to Cryptosporidium infection.

2.2 Traditional taboos and childhood nutrition

Most Nigerians wean their infant at about three to four months of age. Although some as early as the first two months of life by giving food like cereals made from maize (Zea mays), millet (Pennisetum americanum), or guinea corn (Sorghum spp) popularly referred to as pap, akamu, ogi, or koko in Yoruba land, and akamu in Hausa. Staple foods such as mashed, thinned, or pre-chewed form of yam (Dioscorea spp.), rice (Oryza sativa), gari (fermented cassava grits), and cocoyam (Xanthosoma sagittifolium) are then gradually introduced. These traditional menus, that are consistently fed to infants are known to be high in carbohydrate and low protein and may not be adequate to support the development of a strong immune system without supplements. However, the effort to encourage the feeding of a balanced diet to children in some cultures in Nigeria is hampered by the myth that described feeding of protein-rich food like meat, fish and eggs as a taboo, because it is believed that children fed on such meal will later become thieves, witches or wizards.Citation43–Citation46

2.3 Traditional perceptions and management of childhood diarrhoea

In some cultures in Nigeria, rural dwellers believe that diarrhoea is a normal occurrence that must accompany a major milestone such as teething and crawling during the child’s development. Many also believe a heavy infant has diarrhoea to shed weight and thus be able to walk while others believe that diarrhoea is associated with the appearance of the anterior fontanel.Citation47 All these perceptions about diarrhoea do not allow those inclined to them to seek medical attention. Children infected with Cryptosporidium species are usually overwhelmed with chronic diarrhoea that could be fatal due to persistence loss of body fluid and electrolytes.

In many rural communities in Nigeria, childhood diarrhoea is often managed by traditional interventions. In some cultures, diarrhoeic infants are given prescription like burnt corn stalk, raw or partially cooked corn starch, and/or other herbs (concoctions).Citation48 While these treatments may have some effect on the severity of diarrhoea, in most cases, they cannot mitigate the causative pathogen, hence result in chronic infection.

2.4 Birth rituals

Bathing for a new born baby is an important event in most traditional settings in Nigeria. A respected individual in the family usually handles the bathing process which is more or less like a ritual in some culture. It is believed that a child’s destiny is affected negatively if the process is not well conducted.Citation49 In some cultures, herbal concoctions are given to newborn babies for protection from diseases or misfortunes from evil spirits. Furthermore, there is the practice of throwing new born babies into the river as an initiation to the marine life in some traditional settings in the riverine areas of Nigeria. These practices may enable early exposure to water-borne infection through ingestion of water and concoction contaminated with bacteria pathogens, and protozoan agents like Cryptosporidium.

2.5 Traditional child care

It is a common practice in some traditional settings in Nigeria for mothers to engage their parents, siblings or non-relative as a caregiver (nanny) in bringing up their children. Unlike the modern daycare centers where children are kept in environment equipped with nursery facilities that include indoor playground for the maintenance of proper strict hygiene. The situation in the rural setting is, however, different as babies are often allowed to play on bare floor where they could come in contact with food and water that have been contaminated with infected oocyst from animal faeces and other infectious sources of cryptosporidiosis. Direct contact with animals has been implicated as the source of Cryptosporidium infection for growing up children.Citation50–Citation53 While the indirect contact, faecal matters from animals containing oocyst can contaminate environmental samples such as soil, manure and waterCitation54–Citation57 thus, serving as infectious sources of cryptosporidiosis.

3 Conclusion

Although this paper has the obvious limitation of the absence of data that links the aforementioned unhealthy traditional practices with the prevalence of cryptosporidiosis in Nigeria. It however, identified some unwholesome practices that may render ineffective control programmes for a disease like cryptosporidiosis in a multi-cultural population like Nigeria. This review, therefore, suggests the need for comprehensive study of cultural beliefs and practices of a population, as well as the promotion of best health practices among the custodians of different traditions for the design of appropriate strategies for disease prevention and control.

Conflict of interest

None.

Notes

Peer review under responsibility of Alexandria University Faculty of Medicine.

Available online 16 October 2017

References

- Central Intelligence Agency, “Nigeria,” in The World Factbook. <http://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ni.html>; 2011.

- FOS. Federal Office of Statistics; 1989.

- Nigeria Fact Sheet (published by: Nigeria High Commission, New Delhi); 2001:3.

- V.A.OyenugaAgriculture in Nigeria1967Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). FAORome, Italy308

- DuPont HL, Chapell CL, Sterling CR, Okhuysen PC, Rose JB, Jakubowski W. The infectivity of Cryptosporidium parvum in healthy volunteers. N Engl J Med 1195;332:855–859.

- S.A.KjosM.JenkinsP.C.OkhuysenC.L.ChappellEvaluation of recombinant oocyst protein CP41 for detection of Cryptosporidium-specific antibodiesClin Diagn Lab Immunol122005268272

- W.J.SnellingL.XiaoG.Ortega-PierresCryptosporidiosis in developing countriesJ Infect Dev Ctries12007242256

- L.PutignaniD.MenichellaGlobal distribution, public health and clinical impact of the protozoan pathogen CryptosporidiumInterdiscip Perspect Infect Dis2010https://doi.org/10.1155/2010/753512, pii: 753512

- G.NicholsC.LaneN.AsgariRainfall and outbreaks of drinking water related disease and in England and WalesJ Water Health7200918

- J.S.YoderBeach MJ Cryptosporidium surveillance and risk factors in the United StatesExp Parasitol124120103139

- R.M.ChalmersR.SmithK.ElwinF.A.Clifton-HadleyM.GilesEpidemiology of anthroponotic and zoonotic human cryptosporidiosis in England and Wales, 2004–2006Epidemiol Infect1392011700712

- K.L.KochD.J.PhillipsR.C.AberW.L.CurrentCryptosporidiosis in hospital personnel. Evidence for person-to-person transmissionAnn Intern Med1021985593596

- A.P.DaviesR.M.ChalmersCryptosporidiosis BMJ3392009b4168https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b4168

- W.GateiC.N.WamaeC.MbaeCryptosporidiosis: prevalence, genotype analysis, and symptoms associated with infections in children in KenyaAm J Trop Med Hyg7520067882

- J.K.TumwineA.KekitiinwaN.NabukeeraCryptosporidium parvum in children with diarrhoea in Mulago Hospital, Kampala, UgandaAm J Trop Med Hyg682003710715

- K.MolbakN.HojlyngA.GottschauCryptosporidiosis in infancy and childhood mortality in Guinea-Bissau, West AfricaBMJ3071993417420

- M.SodemannM.S.JakobsenK.MolbakC.MartinsP.AabyEpisode specific risk factors for progression of acute diarrhoea to persistent diarrhoea in West African childrenTrans R Soc Trop Med Hyg9319996568

- Duong TH, Dufillot D, Koko J, et al. Digestive cryptosporidiosis in young children in an urban area in Gabon Sante. 1995;5(3):185–8.

- S.MusaA.M.YakubuA.T.OlayinkaPrevalence of Cryptosporidiosis in diarrhoeal stools of children under-five years seen in Ahmadu Bello University Teaching Hospital Zaria, NigeriaNiger J Paed4132014204208

- B.KhaliliM.MardaniFrequency of Cryptosporidium and risk factors related to cryptosporidiosis in under-5-year-old hospitalized children due to diarrhoeaIran J Clin Inf Dis42009151155

- R.SarkarD.KattulaM.R.FrancisRisk factors for cryptosporidiosis among children in a semi urban slum in southern India: a nested case-control studyAm J Trop Med Hyg9120141281137

- F.Javier EnriquezC.R.AvilaJ.Ignacio SantosJ.Tanaka-KidoO.VallejoC.R.SterlingCryptosporidium infections in Mexican children: clinical, nutritional, enteropathogenic, and diagnostic evaluationsAm J Trop Med Hyg61997254257

- R.D.NewmanC.L.SearsS.R.MooreLongitudinal study of Cryptosporidium infection in children in northeastern BrazilJ Infect Dis1801999167175

- Y.AcikgozO.OzkayaK.BekG.GencS.G.SensoyM.HokelekCryptosporidiosis: a rare and severe infection in a pediatric renal transplant recipientPaediatr Transpl162011 Version of Record online

- P.E.Rodriguez-SalinasA.J.Aragon PenaOutbreak of cryptosporidiosis in Guadarrama (Autonomous Community of Madrid)Revista Espãnola de Salud Ṕublica742000527536

- O.BrandonisioA.MarangiM.A.PanaroPrevalence of Cryptosporidium in children with enteritis in Southern ItalyEur J Epidemiol121996187190

- M.K.BhattacharyaT.TekaA.S.FaruqueG.J.FuchsCryptosporidium infection in children in urban BangladeshJ Trop Paediatr431997282286

- F.Solorzano-SantosM.Penagos-PaniaguaR.Meneses-EsquivelCryptosporidium parvum infection in malnourished and non-malnourished children without diarrhoea in a Mexican rural populationRev Invest Clin522000625631

- J.R.CruzF.CanoP.CaceresF.ChewG.ParejaInfection and diarrhoea caused by Cryptosporidium sp. among Guatemalan infantsJ Clin Microbiol2619888891

- K.MolbakP.AabyN.HojlyngA.P.da SilvaRisk factors for Cryptosporidium diarrhoea in early childhood: a case-control study from Guinea-Bissau, West AfricaAm J Epidemiol1391994734740

- M.D.PereiraE.R.AtwillA.P.BarbosaS.A.SilvaM.T.Garcia-ZapataIntra-familial and extra-familial risk factors associated with Cryptosporidium parvum infection among children hospitalized for diarrhoea in Goiania, Goias, BrazilAm J Trop Med Hyg662002787793

- F.A.GualbertoL.HellerEndemic Cryptosporidium infection and drinking water source: a systematic review and metaanalysesWater Sci Technol542006231238

- A.B.AyinmodeB.O.FagbemiL.XiaoMolecular characterization of Cryptosporidium in children in Oyo State, Nigeria: implications for infection sourcesParasitol Res1102012479481

- A.GamboH.I.InaboM.AminuPrevalence of Cryptosporidium oocysts among children with acute gastroenteritis in Zaria, NigeriaBayero J Pure Appl Sci72014155159

- S.A.NassarT.O.OyekaleA.S.OluremiPrevalence of Cryptosporidium infection and related risk factors in children in Awo and Iragberi, NigeriaJ Immunoassay Immunochem2016https://doi.org/10.1080/15321819.2016.1178652

- F.U.ChiraK.E.NkaginiemeR.S.OruamaboCryptosporidiosis in undernourished under five children with diarrhoea at the University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital in NigeriaNiger Postgrad Med J3199659

- A.J.Anejo-OkopiJ.O.OkojokwuMolecular characterization of cryptosporidium in children aged 0–5 years with diarrhoea in JosPan Afr Med J252016253https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2016.25.253.10018

- E.B.BanwatD.Z.EgahB.A.OnileI.A.AngyoE.S.AuduPrevalence of Cryptosporidium infection among Undernourished Children in Jos, Central NigeriaNigerian Postgrad Med J1020038487

- I.P.OkaforF.A.OlatonaO.A.OlufemiBreastfeeding practices of mothers of young children in Lagos, NigeriaNiger J Paed4120144347

- A.S.UmarM.O.OcheBreastfeeding and Weaning Practices in an Urban Slum, North Western NigeriaInt J Trop Dis Health32013114125

- P.C.OsuhorWeaning practices amongst the HausasJ Hum Nutr341980273280

- A.S.JegedeA.S.AjalaO.P.AdejumoS.O.OsunwoleForced feeding practice in Yoruba community of Southwestern evidence from ethnographic researchAnthropologist82006171179

- O.T.AsuD.G.IshorP.J.NdomAfrican cultural practices and health implications for Nigeria rural developmentInt Rev Manage Bus Res22013176183

- Uwaegbute AC. Infant feeding patterns and comparative assessment of formulated weaning foods based on vegetable proteins. Doctoral thesis, University of Nigeria, Nsukka; 1982.

- Onofiok N, Nnanyelugo DO. Nutrient intake of infants of high and low socio-economic groups in Nsukka, Nigeria. Occasional Paper. Nsukka: Department of Home Science and Nutrition, University of Nigeria; 1992.

- D.O.NnanyelugoNutritional status of children in Anambra State: a comprehensive treatise1985University of Nigeria PressNsukka

- B.F.IyunEnvironmental factors, situation of women and child mortality in south western NigeriaSoc Sci Med51200014731489

- M.K.JinadduB.A.FajewonyomiO.OdebiyiFeeding practices of mothers during childhood diarrhoea in rural area of NigeriaNigerian J Paediatr21Suppl19942229

- R.Eva-MaritaWater and healing–experiences from the traditional healers in Ile-Ife, NigeriaNord J Afr Stud1020014165

- J.ShieldJ.H.BaumerJ.A.DawsonCryptosporidiosis – an educational experienceJ Infect211990297301

- N.StefanogiannisM.McLeanH.Van MilOutbreak of cryptosporidiosis linked with a farm eventN Z Med J1142001519521

- M.R.HoekI.OliverM.BarlowOutbreak of Cryptosporidium parvum among children after a school excursion to an adventure farm, south-west EnglandJ Water Health62008333338

- D.CasemoreEpidemiological aspects of human cryptosporidiosisEpidemiol Infect1041990128

- SemieHongKyungjinKimSejoungYoonW.-YoonParkSeoboSimYuJae-RanDetection of Cryptosporidium parvum in environmental soil and vegetablesKorean Med Sci29201413671371

- V.A.PamD.A.DakulK.I.OgbuI.E.EcheonwuS.I.BataThe occurrence of cryptosporidium species in soil and manure in Jos and environs, Plateau State, NigeriaGreener J Biol Sci32013330335

- Stinear T, Matusan A, Hines K, Sandery M. Detection of a single viable Cryptosporidium parvum oocyst in environ-mental water concentrates by reverse transcription-PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol 1996;62:3759–3763.

- E.W.Coutinho FariasR.C.GambaV.H.PellizariDetection of Cryptosporidium spp oocysts in raw sewage and creek water in the city of São Paulo, BrazilBraz J Microbiol3320024143