Abstract

Objective: To present the results of percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) for treating staghorn stones.

Patients and methods: A database was compiled from the computerised files of patients who underwent PCNL for staghorn stones between 1999 and 2009. The study included 238 patients (128 males and 110 females) with a mean (SD) age of 48.9 (14) years, who underwent 242 PCNLs, and included staghorn stones that were present in the renal pelvis and branched into two or more major calyces. PCNL was performed or supervised by an experienced endourologist. All perioperative complications were recorded. The stone-free status was evaluated after PCNL and again after 3 months.

Results: Multiple tracts were needed in 35.5% of the procedures, and several sessions of PCNL were needed in 30% of patients. There were perioperative complications in 54 procedures (22%); blood transfusion was needed in 34 patients (14%). The stone-free rate for PCNL monotherapy was 56.6% (137 patients). Secondary procedures were required for 51 patients (21%), and included shock-wave lithotripsy for 49 and ureteroscopy for two. The 3-month stone-free rate was 72.7% (176 patients). Multiple tracts resulted in an insignificantly higher overall complication rate than with a single tract (P = 0.219), but the reduction in the haemoglobin level was statistically significant with multiple tracts (P = 0.001).

Conclusions: PCNL for staghorn stones must be done by an experienced endourologist in a specialised centre with all the facilities for stone management and treatment of possible complications. The patients must be informed about the range of stone-free and complication rates, and the possibility of multiple sessions or secondary procedures.

Abbreviations:

Introduction

In the last two decades the treatment of staghorn stones has changed from traditional open surgery to minimally invasive methods such as percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) monotherapy, combinations of PCNL and ESWL, and ESWL monotherapy. The last two AUA Guideline Panels recommended PCNL as the first choice for treating staghorn calculi [Citation1,Citation2]. The advantages of PCNL are mainly a result of avoiding the long muscle-cutting lumbar incision of open surgery. Therefore patients who undergo PCNL benefit from decreased analgesic requirements, and a shorter hospital stay and convalescence period. Moreover, the stone-free rates after PCNL for staghorn stones were significantly higher than after ESWL.

However, PCNL for staghorn stones is a demanding surgical procedure. Mastering the techniques of percutaneous renal access, intracorporeal lithotripsy, the use of rigid and flexible nephroscopic manipulations is essential for safe PCNL in this group of stones. In addition, there can be a need for multiple percutaneous tracts or several sessions of PCNL to remove all stone branches [Citation3], and secondary procedures such as ESWL might be required for residual fragments. The main concern about PCNL for staghorn stones was its potentially dangerous morbidity, e.g. haemorrhagic complications, sepsis and adjacent-organ injuries [Citation4,Citation5]. These are the reasons for restricting the use of PCNL for treating staghorn stones to tertiary-care stone centres that have a high volume of cases, experienced endourologists, and all the instruments for stone management and treatment of complications.

In this report we present our experience from a tertiary-care centre in treating staghorn calculi, focusing on technical points, complication and success rates.

Patients and methods

Patients

The computerised files of patients who underwent PCNL for the treatment of staghorn stones between 1999 and 2009 were reviewed. The study included staghorn stones that were present in the renal pelvis and branched into two or more major calyces (i.e. partial and complete staghorn stones). Giant staghorn stones that were associated with markedly deformed calyceal anatomy were not included in the study because they were treated with open surgery. Borderline stones that branched into one major calyx were also excluded from this study. The study included 238 patients (128 male, 110 female) with mean (SD, range) age of 48.9 (14, 4–74) years.

Preoperative preparation

Preoperative laboratory investigations included urine analysis and culture, serum creatinine estimation, a complete blood count, liver function tests and prothrombin concentration. Radiological investigations included IVU or non-contrast CT (NCCT), the latter being used in patients with a high serum creatinine level (>1.6 mg/dL), or those allergic to the intravenous contrast medium. Patients with positive urine cultures were treated with specific antibiotics for 5 days. All patients received intravenous third-generation cephalosporins at the time of induction of anaesthesia.

Technique of PCNL for staghorn stones

The technique of PCNL for staghorn stones was as follows. General anaesthesia was used for all patients; a ureteric catheter was fixed with the patient in the lithotomy position. Percutaneous renal access was then made using multidirectional C-arm fluoroscopic guidance (BV Pulsera, Philips Medical Systems, Eindhoven, the Netherlands). The skin was punctured at the posterior axillary line. All planned tracts were made and guidewires were secured inside the calyceal system before dilatation of any tract. PCNL was completed in the same session, except in patients with a high serum creatinine level, or if the initial puncture drained purulent fluid. Dilatation was performed with Alken coaxial telescopic dilators (Karl Storz Endoskope, Tuttlingen, Germany) to 30 F for the primary tract where a rigid nephroscope of 26 F (Karl Storz Endoskope) was used through an Amplatz sheath (Boston Scientific Corp., Natick, MA, USA). In some cases, secondary tracts were dilated to 24 F and a rigid nephroscope of 18.5 F was used. The stone was disintegrated with ultrasonic (Calcuson, Karl Storz Endoskope) or pneumatic lithotripters (Swiss Lithoclast, EMS, Nyon, Switzerland). Intraoperative fluoroscopy and flexible nephroscopy (CYF-5, Olympus Surgical and Industrial Inc., Center Valley, PA, USA) were used for the detection and retrieval of residual stones. In some cases, remote calyces were irrigated with a percutaneous needle or Ellik evacuator (Bard, Madison, GA, USA) through the nephroscope sheath to force small residual fragments to the renal pelvis. At the end of the procedure a 22 F nephrostomy tube was placed in the primary tract while a 16 F nephrostomy tube was placed in the secondary tract.

Postoperative evalution

On the next day, a plain abdominal film was taken to detect radio-opaque stones, while NCCT was used for radiolucent stones. Residual stones that were accessible through the present nephrostomy tract were managed by ‘second-look’ PCNL, while ESWL was used for inaccessible residual fragments of 4–10 mm. The stone-free status was re-evaluated after 3 months for patients who required ESWL with NCCT. Complications and haemoglobin deficits were compared between patients who needed a single tract and those who required multiple percutaneous tracts.

Statistical analysis

The data were analysed statistically using the chi-square test for categorical variables and a t-test for continuous variables, with P < 0.05 considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

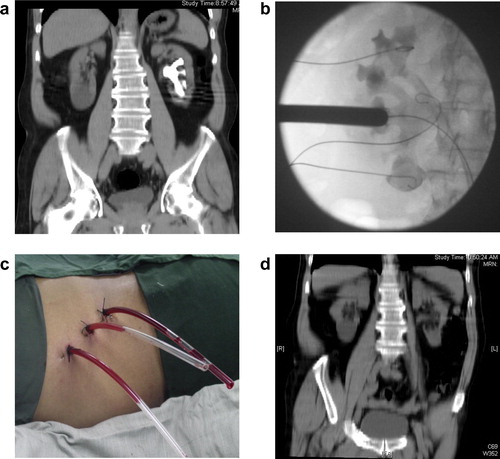

The patients underwent 242 PCNLs (142 on the left side, 92 on the right and four bilateral); in 72 PCNLs (30%) the stones were recurrent after previous intervention. Radiolucent stones were present in 63 patients (26%). In 61 procedures (25%) an ultrasonography-guided nephrostomy tube was placed by a radiologist in the radiology department to drain an infected obstructed kidney before PCNL, then PCNL was performed after clearing the infection (negative urine culture). In the remaining 181 procedures (75%) the percutaneous tract was established by an experienced endourologist and PCNL was completed in the same session. All procedures were conducted with the patient prone, except for four morbidly obese patients who were treated while supine. Multiple tracts were needed in 86 (35.5%) procedures (two tracts in 73 and three in 13). shows the images before, during and after PCNL of a patient with complete staghorn stones that required multiple tracts. Supracostal punctures were used in 88 cases (36.4%).

Figure 1 (a) Preoperative NCCT (coronal view) showing a complete staghorn stone in the left kidney. (b) Intraoperative fluoroscopic image during dilatation of the middle calyceal access, showing multiple guidewires in the upper, middle and lower calyceal groups. (c) Intraoperative view showing the three nephrostomy tubes. (d) Postoperative unenhanced CT (coronal view) showing no residual stones.

There were perioperative complications in 54 patients (22%); some had more than one complication. Intraoperative complications included significant bleeding that required stopping the procedure in 23 (9.5%), and perforation of the renal pelvis in six (2.5%). Postoperative complications included haematuria in 15 patients (three of them had also intraoperative bleeding), urinary leakage in 11, fever in six, hydrothorax in four and perirenal urinoma in two. A blood transfusion was needed in 34 patients (14%). Bleeding was treated successfully by clamping the nephrostomy tube and haemostatic drugs in 26 cases, while eight (3.4%) required angiographic embolisation, and one patient died during exploration for severe bleeding. Urinary leakage was treated by fixing JJ ureteric stents. Hydrothorax was treated with an intercostal chest tube, and the urinoma was drained with a percutaneous tube drain. Fever was treated with antibiotics and antipyretics.

Several sessions of PCNL were needed in 73 (30%) cases (two sessions in 65 and three in eight). The success rate of PCNL monotherapy was 79%, as 137 cases (56.6%) were free of stones, 53 had small (<4 mm) residual stones in peripheral calyces, and 51 (21%) had significant residual stones. Secondary procedures for managing significant residual stones included ESWL for 49 patients and ureteroscopy for two. The mean (range) number of procedures per patient was 1.6 (1–4), and the hospital stay was 5.2 (2–21) days. At 3 months the stone-free rate increased to 72.7% (176 patients). The remaining patients with residual stones were followed.

When the results of PCNL in those requiring single vs. multiple tracts were compared (), multiple tracts resulted in a statistically significant reduction of haemoglobin level (P = 0.001), but the higher overall complication rate with multiple tracts was not statistically significant (P = 0.219).

Table 1 Comparison between the results of PCNL for staghorn stones in cases requiring single or multiple tracts.

Two of the four morbidly obese patients who underwent PCNL while supine became free of stones, while the other two had small residual stones. There was postoperative haematuria in one of these four patients, and it was managed conservatively.

Discussion

Since the introduction of PCNL for treating renal stones there have been marked improvements in the techniques and instruments that have resulted in using PCNL for treating complex and staghorn stones. In 1983 Clayman et al. [Citation6] reported the feasibility and safety of PCNL for treating staghorn stones. Currently it is the treatment of choice for patients with large, complex and staghorn renal stones [Citation1–Citation3,Citation7]. The goals of treatment of a staghorn stone are complete stone clearance with minimal morbidity [Citation1–Citation3].

The stone-free rates after PCNL monotherapy for staghorn stones were reported to range from 49% [Citation8] to 78% [Citation9]. The stone-free rate of 56.6% in the present study is higher than that of 49% reported by Al-Kohlany et al. [Citation8], because they were treating complete staghorn stones while we included partial and complete staghorn stones. However, our result was lower than the 78% reported by Soucy et al. [Citation9], who included stones branching into only one calyx (borderline staghorn stone) in two-thirds of their patients. Therefore, it is expected that the more the branching of the staghorn stone, the lower the stone-free rate of PCNL monotherapy. Moreover, the stone-free rate in the present patients was determined by NCCT, unlike in many series of PCNL for staghorn stones. Evaluating the stone-free rate using NCCT provides more accuracy in detecting small residual stones [Citation10].

The stone-free rate of 72.7% at 3 months in the present study was comparable to the 66% rate for combined therapy that was reported in the last AUA guidelines [Citation2]. Streem et al. [Citation11] reported a stone-free rate of 63–70% when they used ‘sandwich’ therapy, where PCNL was the terminal procedure (PCNL–ESWL–PCNL). In the present study nephroscopy (the last step of ‘sandwich’ therapy) was not used to retrieve small residual stones (<4 mm). The 30% incidence of ‘second-look’ PCNL and 21% incidence of secondary procedures in the present study highlight the importance of patient counselling before PCNL for staghorn stones. The patient must be aware that the chance of needing multiple interventions to become free of stones might be up to 50%.

Potentially significant morbidity or even death was reported with PCNL in large-scale series [Citation5,Citation12,Citation13]. Furthermore, PCNL is more challenging when used for treating staghorn stones. The AUA nephrolithiasis guidelines panel on staghorn calculi reported complication rates of 7–27% and a transfusion rate of up to 18% [Citation2]. The complication rate of 22% and transfusion rate of 14% in the present study were comparable with these results. Severe bleeding requiring angiographic embolisation was the most dangerous complication in the present study. It was encountered in 3.4% of patients and lead to the death of one patient. This high incidence of embolisation was attributed to the complexity of the procedure and the need for multiple tracts in 35.5% of patients. A staghorn stone was identified as a risk factor for severe bleeding after PCNL [Citation4] and multiple tracts were detected as a risk factor for blood loss during PCNL [Citation13].

There are many factors that can maximise the benefits of PCNL when treating staghorn stones, and at the same time minimise the complications. First, it requires preoperative strategic thinking, planning the number, sites and direction of the access tracts after a thorough revision of all radiological images. It is essential to adequately study the position of the stone and its branches inside the pelvicalyceal system. NCCT and contrast-enhanced CT with three-dimensional reconstruction have been very useful in planning the percutaneous access [Citation3]. A supracostal skin puncture is indicated when there is a large branch of the staghorn stone in the upper calyx. It has the benefit of providing an easy access to the renal pelvis and, in some cases the lower calyx, through one tract because the surgeon works along the longitudinal axis of the kidney. The main concern of supracostal access is the risk of pleural injury [Citation14].

Second, renal access should be done by endourologists with considerable experience in percutaneous surgery, because they will be most familiar with the pelvicalyceal anatomy and the surgical procedure [Citation3]. Third, when deciding to use multi-tract PCNL it is advisable to place all the tracts and fix all guidewires before starting dilatation of the first tract. Fourth, complete removal of the stone is crucial to eradicate any causative organisms, relieve obstruction, and prevent further stone growth [Citation15]. This can be achieved by using flexible nephroscopy during the primary or the second-look PCNL [Citation3,Citation16], using multi-tract PCNL [Citation17] or using ESWL to treat residual stones. Last, the surgeon must gain a balance between complete stone clearance and acceptable patient morbidity. Therefore, when significant complications develop, e.g. bleeding, the procedure should be terminated. Kukreja et al. [Citation13] recommended staging the procedure of PCNL in patients with a large stone burden or if intraoperative complications developed.

In staghorn stones with multiple large branches, percutaneous access to all the calyces can be difficult through one tract. In these cases the multi-tract technique was reported as a viable alternative to single-tract PCNL with flexible nephroscopy or ureterorenoscopy [Citation17]. In the present study, multi-tract cases were associated with a relative increase in the complication rate and haemoglobin deficit. Therefore, preoperative planning of the procedure and choosing the appropriate technique must be individualised for each patient.

The retrospective nature of the present study was a limiting factor because there could be some bias in the treatment strategies. For example, we knew that flexible nephroscopy was used in some cases but we did not know exactly how often, because this was not written in the operative notes of all patients. Another limitation was the lack of a metabolic evaluation in many patients because stone analysis and metabolic tests were not used routinely for all patients.

In conclusion, PCNL is the mainstay for treating staghorn stones, but it represents the most challenging percutaneous renal surgery. It must be done by experienced endourologists in a specialised centre with all the facilities for stone management and treatment of possible complications. The patients must be informed about the ranges of stone-free and complication rates, and the possibility of multiple sessions or secondary procedures.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Notes

Peer review under responsibility of Arab Association of Urology.

References

- J.W.SeguraG.M.PremingerD.G.AssimosS.P.DretlerR.I.KahnJ.E.LingemanetalNephrolithiasis Clinical Guidelines Panel summary report on the management of staghorn calculi. The American Urological Association Nephrolithiasis Clinical Guidelines PanelJ Urol151199416481651

- G.M.PremingerD.G.AssimosJ.E.LingemanS.Y.NakadaM.S.PearleJ.S.WolfJr.AUA Nephrolithiasis Guideline Panel Chapter 1: AUA guideline on management of staghorn calculi: diagnosis and treatment recommendationsJ Urol173200519912000

- M.DesaiP.JainA.GanpuleR.SabnisS.PatelP.ShervastavDevelopments in technique and technology: the effect on the results of percutaneous nephrolithotomy for staghorn calculiBJU Int1042009542548

- A.R.El-NahasA.A.ShokeirA.M.El-AssmyT.MohsenA.M.ShomaI.ErakyetalPost-percutaneous nephrolithotomy extensive hemorrhage. A study of risk factorsJ Urol1772007576579

- M.S.MichelL.TrojanJ.J.RassweilerComplications in percutaneous nephrolithotomyEur Urol512007899906

- R.V.ClaymanV.SuryaR.P.MillerW.R.Casteneda ZunegaK.AmplatzP.H.LangePercutaneous nephrolithotomy; an approach to branched and staghorn renal calculiJAMA25019837375

- D.S.MorrisJ.T.WeiD.A.TaubR.L.DunnJ.S.WolfJrB.K.HollenbeckTemporal trends in the use of percutaneous nephrolithotomyJ Urol175200617311736

- K.M.Al-KohlanyA.A.ShokeirA.MosbahT.MohsenA.M.ShomaI.ErakyetalTreatment of complete staghorn stones: a prospective randomized comparison of open surgery versus percutaneous nephrolithotomyJ Urol1732005469473

- F.SoucyR.KoM.DuvdechaiL.NottJ.D.DenstedtH.RazviPercutaneous nephrolithotomy for staghorn calculi. A single center experience of 15 yearsJ Endourol10200915

- Y.OsmanN.El-TabeyH.RefaiA.ElnahasA.ShomaI.ErakyetalDetection of residual stones after percutaneous nephrolithotomy: role of non-enhanced spiral computerized tomographyJ Urol1792008198200

- S.B.StreemA.YostB.DolmatchCombination ‘sandwich’ therapy for extensive renal calculi in 100 consecutive patients. Immediate, long-term and stratified results from a 10-year experienceJ Urol1581997342345

- M.DuvdevaniH.RazviM.SoferD.T.BeikoL.NottB.H.ChewetalThird prize: contemporary percutaneous nephrolithotripsy: 1585 procedures in 1338 consecutive patientsJ Endourol212007824829

- R.KukrejaM.DesaiS.PatelS.BapatM.DesaiFactors affecting blood loss during percutaneous nephrolithotomy: prospective studyJ Endourol182004715722

- R.MunverF.C.DelvecchioG.E.NewmanG.M.PremingerCritical analysis of supracostal access for percutaneous renal surgeryJ Urol166200112421246

- A.R.El-NahasI.ErakyA.A.ShokeirA.M.ShomaA.M.El-AssmyN.A.El-TabeyetalLong-term results of percutaneous nephrolithotomy for treatment of staghorn stonesBJU Int1082011750754

- M.A.BeaghlerM.W.PoonJ.W.DushinskiJ.E.LingemanExpanding role of flexible nephroscopy in the upper urinary tractJ Endourol1319999397

- A.P.GanpuleM.DesaiManagement of the staghorn calculus: multiple-tract versus single-tract percutaneous nephrolithotomyCurr Opin Urol182008220223