Abstract

Objectives:To establish a clinical care pathway that plans for hospital discharge the day after percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL), to evaluate the safety, effectiveness and feasibility of this pathway, and to identify factors associated with a postoperative length of hospital stay (LOS) of >1 day. PCNL is the treatment of choice for patients with large kidney stones and those in whom extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy has failed, and the mean LOS is typically 2–5 days.

Patients and methods: We retrospectively reviewed the charts of 109 patients (mean age 57.4 years; 58 men, 53%) who had PCNL between 2006 and 2009. All had nephrostomy tubes placed after surgery. The patients’ demographics, LOS, incidence of complications, clinical outcomes, stone-free rates, number of early postoperative emergency-room visits, need for subsequent admission and/or other procedures, were noted and analysed. The modified Clavien classification was used to describe the postoperative complications. Bivariate analyses were used to test for associations between LOS and other variables.

Results: The mean (range) stone size was 2.2 (0.9–5.9) cm, and the mean (SEM) LOS was 1.7 (0.13) days. Of the 109 patients, 20% had a LOS of >1 day for surgical, 3% for medical and 5% for social reasons. The stone-free rate was 89%. There was no difference in the number of subsequent hospital visits or ancillary procedures for patients discharged after one or more postoperative nights. No variables were associated with a longer LOS.

Conclusions: An overnight hospital stay after PCNL is safe and represents an effective strategy for improved bed use in selected patients. A longer LOS was not affected by patient age or body mass index, stone size or operative time. We continue to use our clinical care pathway, as supported by these data.

Introduction

Percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) has become the first-line intervention for patients with a significant stone burden, because of continued improvements in safety, stone-free rates and length of hospital stay (LOS) [Citation1, Citation2] . Although the last is much lower than that for open kidney surgery, it has remained typically at 2–5 days after PCNL because of the presence of the nephrostomy tube (NT) left in situ to drain the kidney, tamponade the nephrostomy tract and to permit an easy re-entry into the collecting system. Some authors have addressed this issue by advocating tubeless outpatient PCNL in highly selected patients [Citation3–Citation5] .

We have approached the goal of a shorter postoperative LOS by developing a clinical care pathway that plans for routine overnight NT drainage and next-day discharge in patients undergoing PCNL. Here we report our experience with this strategy.

Patients and methods

We retrospectively reviewed the charts of 109 patients who had a PCNL between 2006 and 2009. Only patients on anticoagulants requiring perioperative bridging, and those in whom antiplatelet medications could not be safely discontinued before surgery, were excluded. All patients were evaluated by a history, physical examination, urine analysis, urine culture, serum creatinine level and renal ultrasonography or abdominal CT before surgery.

Procedure

A 5-F open-ended ureteric catheter was placed cystoscopically before establishing percutaneous access, by an interventional radiologist and under fluoroscopic guidance. The tract was dilated with a combination of Amplatz dilators and a balloon. The stone(s) were removed by graspers with or without ultrasonic/pneumatic lithotripsy. Once complete clearance was confirmed fluoroscopically and endoscopically, a 20–24 F NT was positioned in the collecting system and sutured to the skin. JJ ureteric stents were not inserted routinely.

Postoperative care

The ureteric catheter was removed but the Foley catheter and NT were kept connected to straight drainage overnight. If the patient was stable and afebrile overnight, the NT was clamped at 06.00 h for at least 4 h and then removed if there was no change, and the patient was then discharged. If pain or fever (>38 °C) developed after clamping, the NT was unclamped and another trial of clamping was done on the next day. If pain and/or fever recurred the NT was unclamped and a nephrostogram is taken once the pain and/or fever had settled. Patients were given analgesics, NSAIDs and/or narcotics as needed. Vital signs were assessed routinely. All patients had a complete blood count, and electrolytes and serum creatinine levels assessed in the morning after surgery.

Follow-up

Before discharge patients were informed about the possibility of having LUTS, mild haematuria and/or drainage from the NT site for a couple of days. They were told to return to the emergency department if they developed fever, chills, vomiting or worsening pain. Patients were followed for 3 months after surgery for a metabolic evaluation and imaging as indicated.

Outcomes

The primary outcome measure was LOS; the secondary outcome measures were the number of complications, clinical outcomes, stone-free rates, number of early postoperative emergency room visits and the need for subsequent admission and/or other procedures. Demographic and perioperative data were reported as the mean (SEM) for quantitative variables. The modified Clavien classification was used to describe the postoperative complications. A two-tailed t-test with 95% CI was used to compare variables before and after surgery. The patients were divided into two groups according to the LOS (<1 day and >1 day). The LOS served as the dependent variable in every model, and each remaining variable was individually fitted into a logistic regression model as the independent variable. In all tests, P < 0.05 was considered to indicate significance.

Results

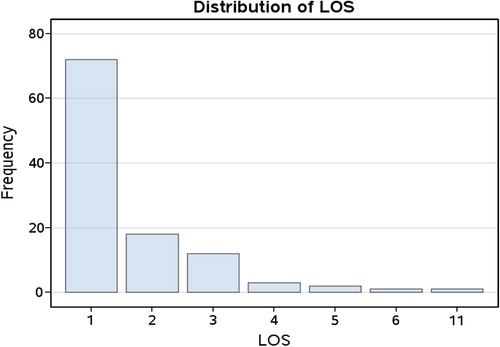

The patients’ demographics and stone characteristics are shown in , and shows the distribution of LOS. The mean (SEM) was 1.7 (0.13) days, with 72 (66%) of patients discharged on the first day after surgery.

Table 1 A summary of the characteristics of the 109 patients, and the characteristics of the stones.

Two patients had intraoperative complications. One had a transverse colon injury during the renal access. This was identified during surgery, the procedure aborted and the patient managed conservatively with Malecot catheter drainage. Another had significant bleeding from his access site, which obscured visibility; an NT was placed, the procedure aborted and a second successful attempt was completed 2 days later. Four patients required a JJ stent after surgery (two in each group). Five patients required elective ESWL for residual stones (three in the LOS <1 day group and two in the LOS >1 day group). Two patients required ureteroscopy to remove ureteric stone fragments (one in each group). Eleven others had early postoperative complications (). There was no significant difference in the intraoperative complication rate between the groups (). The postoperative complication rate was higher in the LOS >1 day group (P < 0.001). Nineteen patients needed their NT unclamped, for pain in 12, fever in four and nonspecific reasons in three. There was no difference in the number of subsequent hospital visits or ancillary procedures for patients discharged after one or more nights (). No patients required a blood transfusion.

Table 2 The Clavien classification of complications.

Table 3 The association between complications, need for re-admission, patient, stone and operative variables, and LOS.

Table 4 A summary of subsequent hospital visits and ancillary procedures.

In the targeted stone-free rate was 89% but was lower for those patients requiring a longer LOS ( and ). Associations between LOS and other variables are also summarised in . Of the 37 patients with a LOS of >1 day the reasons were surgical in 29 (27% of the total number of patients), medical in three (3%) and social in four (4%).

Discussion

We assessed the feasibility of an overnight stay after PCNL by reviewing retrospectively the outcomes of 109 patients. There was no significant difference in the intraoperative complication rate, number of subsequent hospital visits or ancillary procedures between the groups with an overnight or longer LOS. The postoperative complication and stone-free rates were higher in the group with a LOS of >1 day (P < 0.001).

PCNL is the most effective treatment for patients with a large stone burden, complex renal stone disease or the goal of being immediately stone-free [Citation6]. Reducing the LOS is a key strategy to improve the cost-effectiveness of PCNL, and several techniques have been tried.

Tubeless PCNL, often with postoperative ureteric stent drainage, has been shown in highly selected patients to be a safe modification to limit the need for a hospital stay [Citation3–Citation5] . The stone clearance rates are comparable to those of the conventional PCNL, with less postoperative urinary leakage and pain [Citation7]. Early NT removal can lead to similar benefits of an equivalent need for analgesia, a decrease in haemoglobin loss, and in LOS (>70 h for both groups) compared with tubeless PCNL [Citation8]. Avoiding a postoperative ureteric stent eliminates the discomfort associated with it and the need for its removal. The advantages of NT drainage include adequate renal drainage, the tamponade of any tract bleeding, reduced urinary extravasation and it allows the nephrostomy tract to mature for a ‘second look’.

Residual stone fragments after PCNL can occur in up to 8% of patients [Citation9]. The size and location of these residual fragments correlate with future stone-related events. Larger fragments are more likely to require a secondary surgical intervention. ‘Clinically insignificant residual fragments’ is a term used to describe fragments of <4–5 mm left after ESWL and PCNL and that are asymptomatic, not obstructive and not infectious [Citation10, Citation11] . Urologists should consider all possible measures to avoid leaving residual fragments, carefully identify them during surgery or afterwards, and deal with them appropriately. Residual fragments of <25 mm2 and those situated in the renal pelvis after PCNL have the best chance of clearance; most will clear spontaneously by 3 months [Citation12]. The options to intervene include a ‘second look’ nephroscopy, flexible ureteroscopy, ESWL or active surveillance [Citation13, Citation14] . In the present series stone clearance was confirmed by intraoperative fluoroscopy and endoscopy.

Our standard care plan was used for all patients who did not have a significant bleeding diathesis; 66% had their NT removed and were discharged on the day after surgery. There was a delayed discharge when there was an unexpected complication during or after surgery. As many of our patients live a long way from the hospital, we always delayed discharge if there was any question as to its safety, e.g. adverse weather conditions, lack of support at home or a variety of other social issues. Few patients required re-admission.

Only two patients had complications during surgery that requiring the surgical procedure to be abandoned; one for a colonic perforation and one for excessive bleeding. These problems are also uncommonly reported [Citation15]. The postoperative complication rate was 12% and included several minor problems similar to those reported previously [Citation15, Citation16] .

The definition of the stone-free rate is variable. Our use of intraoperative fluoroscopy and end-of-case nephroscopy to confirm removal of all targeted stones gave a success rate of 89%. In some cases not every stone fragment was pursued, e.g. if there was an obstructing stone in the renal pelvis and another in a difficult-to-access calyceal diverticulum, the latter would typically be ignored if the potential risk of multiple accesses was considered to outweigh the potential benefit. In the present series we confirmed the clearance of the targeted stone(s) fluoroscopically and endoscopically at the end of the procedure.

Patient age, body mass index (BMI), stone size and operating time had no effect on the LOS. These results are similar to those reported previously [Citation17–Citation19] . Our postoperative complication rate was higher in the group who stayed for >1 day, as expected (P < 0.001), and was typically the reason for the longer stay. The stone-free rate was lower in the group who had a LOS of >1 day (P = 0.02) as some of them need to stay longer for a second procedure.

This is the first published study to assess the feasibility of an overnight stay after a conventional PCNL procedure. Outpatient tubeless PCNL has been reported, but it was done in a highly selected groups of patients [Citation20, Citation21] . Due to limited resources and funds in most healthcare systems, there is an advantage to striving for the shortest possible LOS that can safely be achieved. We show that this can be done effectively even when leaving a NT after surgery, with the advantages that it gives reliable urinary drainage, haemostatic tamponade of the percutaneous tract and maintenance of access for further percutaneous manipulation.

We acknowledge the limitations of our study, including its retrospective design, the relatively few patients, and that it is the experience of one surgeon.

An overnight hospital stay after PCNL is safe represents an effective strategy for improved bed use in selected patients. Further prospective studies are needed to confirm and expand upon these findings.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest to declare.

Source of funding

There was no funding.

Notes

Peer review under responsibility of Arab Association of Urology.

References

- Türk C, Knoll T, Petrik A, Sarica K, Seitz C, Straub M. EAU. Guidelines on Urolithiasis 2012 Available at http://www.uroweb.org/gls/pdf/20_Urolithiasis_LR%20March%2013%202012.pdf.

- A.SkolarikosG.AlivizatosJ.J.de la RosettePercutaneous nephrolithotomy and its legacyEur Urol4720052228

- B.LojanapiwatS.SoonthornphanS.WudhikarnTubeless percutaneous nephrolithotomy in selected patientsJ Endourol152001711713

- H.N.ShahH.S.SodhaA.A.KhandkarS.KharodawalaS.S.HegdeM.B.BansalA randomized trial evaluating type of nephrostomy drainage after percutaneous nephrolithotomy: small bore v tubelessJ Endourol22200814331439

- T.J.CrookC.R.LockyerS.R.KeoghaneB.H.WalmsleyA randomized controlled trial of nephrostomy placement versus tubeless percutaneous nephrolithotomyJ Urol1802008612614

- C.E.ProbstJ.D.DenstedtH.RazviPreoperative indications for percutaneous nephrolithotripsy in 2009J Endourol23200915571561

- C. F.BorgesA.FregonesiD. C.SilvaA. D. J.SasseSystematic review and meta-analysis of nephrostomy placement versus tubeless percutaneous nephrolithotomyJ Endourol 2010; October 19 [Epub ahead of print].

- S.MishraR.B.SabnisA.KurienA.GanpuleV.MuthuM.DesaiQuestioning the wisdom of tubeless percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL): a prospective randomized controlled study of early tube removal vs tubeless PCNLBJU Int106201010451048

- J.D.RamanA.BagrodiaA.GuptaK.BensalahJ.A.CadedduY.LotanetalNatural history of residual fragments following percutaneous nephrostolithotomyJ Urol181200911631168

- L.K.Carr A.D’J.HoneyM.A.JewettD.IbanezM.RyanC.BombardieretalNew stone formation. A comparison of extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy and percutaneous nephrolithotomyJ Urol1996; 155: 1565-1567.

- A.KhaitanN.P.GuptaA.K.HemalP.N.DograA.SethM.AronPost-ESWL, clinically insignificant residual stones: Reality or myth?Urology5920022024

- A.GanpuleM.DesaiFate of residual stones after percutaneous nephrolithotomy: a critical analysisJ Endourol232009399403

- A.SkolarikosA.G.PapatsorisDiagnosis and management of postpercutaneous nephrolithotomy residual stone fragmentsJ Endourol23200917511755

- A.R.El-NahasI.ErakyA.A.ShokeirA.M.ShomaA.M.El-AssmyN.A.El-TabeyetalPercutaneous nephrolithotomy for treating staghorn stones: 10 years of experience of a tertiary-care centreArab J Urol 2012; in press Available online 18 April.

- M.S.MichelL.TrojanJ.J.RassweilerComplications in percutaneous nephrolithotomyEur Urol512007899906

- C.SaussineE.LechevallierO.TraxerPCNL; technique, results and complicationsProg Urol182008886890

- A.SahinN.AtsüE.ErdemS.OnerC.BilenM.BakkalogluetalPercutaneous nephrolithotomy in patients aged 60 years or olderJ Endourol152001489491

- F.A.AlyamiT.A.SkinnerR.W.NormanImpact of body mass index on clinical outcomes associated with percutaneous nephrolithotomyCan Urol Assoc J 2012 May 15: 1–5 doi: 10.5489/cuaj.11229. [Epub ahead of print].

- A.BagrodiaA.GuptaJ.D.RamanK.BensalahM.S.PearleY.LotanImpact of body mass index on cost and clinical outcomes after percutaneous nephrostolithotomyUrology722008756760

- D.BeikoL.LeeOutpatient tubeless percutaneous nephrolithotomy: the initial case seriesCan Urol Assoc J42010E86E90

- G.M.PremingerR.V.ClaymanT.CurryH.C.RedmanP.C.PetersOutpatient percutaneous nephrostolithotomyJ Urol1361986355357