?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Objective:

To determine from urodynamic data what causes an increased postvoid residual urine volume (PVR) in men with bladder outlet obstruction (BOO), urethral resistance or bladder failure, and to determine how to predict bladder contractility from the PVR.

Patients and methods:

We analysed retrospectively the pressure-flow studies (PFS) of 90 men with BOO. Nine patients could not void and the remaining 81 were divided into three groups, i.e. A (30 men, PVR < 100 mL), B (30 men, PVR 100–450 mL) and C (21 men, PVR > 450 mL). The division was made according to a receiver operating characteristic curve, showing that using a threshold PVR of 450 mL had the best sensitivity and specificity for detecting the start of bladder failure.

Results:

The filling phase showed an increase in bladder capacity with the increase in PVR and a significantly lower incidence of detrusor overactivity in group C. The voiding phase showed a significant decrease in voided volume and maximum urinary flow rate (Qmax) as the PVR increased, while the urethral resistance factor (URF) increased from group A to B to C. The detrusor pressure at Qmax (PdetQmax) and opening pressure were significantly higher in group B, which had the highest bladder contractility index (BCI) and longest duration of contraction. Group C had the lowest BCI and the lowest PdetQmax.

Conclusions

In men with BOO, PVR results from increasing outlet resistance at the start and up to a PVR of 450 mL, where the bladder reaches its maximum compensation. At volumes of >450 mL, both the outlet resistance and bladder failure are working together, leading to detrusor decompensation.

Introduction

The natural history of untreated BOO has been explained by the concept of detrusor compensation to outlet resistance, followed by eventual decompensation [Citation1–Citation3]. Bladder compensation occurs by detrusor hypertrophy and an increased power of contractility to maintain effective emptying despite the obstruction [Citation4]. The postvoid residual urine volume (PVR) starts to increase as a result of the relative imbalance between bladder contractility and increased outlet resistance, leading to chronic retention of urine [Citation5].

It has been generally accepted by many urologists that a PVR of <100 mL is not significant, whilst if the PVR is >100 mL, then chronic retention starts to develop [Citation6–Citation8]. Whether the causes of chronic retention and progressive accumulation of the PVR are related to bladder failure or increased outlet resistance or both remains debatable.

The aim of the present study was to find a urodynamic explanation for the increasing PVR urine in men with chronic retention caused by BOO. We determined from pressure-flow data whether an increased outlet resistance alone or bladder failure alone is responsible for the increasing PVR or whether they might work together at a certain point. The second aim of the study was to assess whether it is possible to predict bladder contractility from the PVR or not.

Patients and methods

After approval from the Institutional Review Board we retrospectively analysed the urodynamic pressure-flow studies (PFS) of all men referred to our urodynamic unit with BOO over the last 2 years. The patients had to score >7 on the IPSS to be included in the study. Patients with neurogenic diseases or diabetes mellitus, and those on chronic use of anticholinergics or antidepressants were excluded from the study, to exclude detrusor underactivity.

In the filling phase of urodynamics we assessed the bladder capacity, compliance and the presence or absence of detrusor overactivity. In the voiding phase, standard ICS nomograms were used to diagnose BOO. We determined the voided volume, maximum urinary flow rate (Qmax), opening pressure, the detrusor pressure at Qmax (PdetQmax), duration of contraction, the bladder contractility index (BCI) and the urethral resistance factor (URF). Bladder contraction is defined as any rise in detrusor pressure (during voiding) above the end-filling pressure. The duration of contraction was determined by the total contractility time, defined as the duration from the start of the rise in Pdet above the end-filling pressure to the decline of Pdet below the end-filling pressure.

To obtain the BCI we used the equation BCI = PdetQmax + 5 Qmax, where BCI ⩾ 100 is considered good contractility and BCI < 100 is considered weak contractility [Citation9]. The URF was measured manually using the equationwhere d is a constant (3.8 × 10−4 and Q is the corresponding flow rate for the measured Pdet, and where a URA of <29.5 represents a normal urethral resistance and a URA of ⩾29.5 an increased urethral resistance [Citation10].

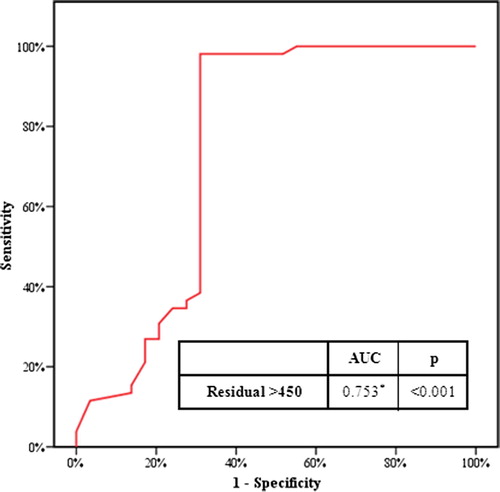

A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was constructed to test the sensitivity and specificity of various thresholds of PVR at which bladder contractility changed from good (BCI ⩾ 100) to weak (BCI < 100). The different thresholds tested included 300, 350, 400, 450 and 500 mL. The ROC curve showed that a threshold of 450 mL had the best sensitivity and specificity to detect this change (98% and 68.9%, respectively) with a positive predictive value of 85% and a negative predictive value of 92.2%, and overall accuracy of 87.7% (). Thus we divided the patients into three groups according to a threshold PVR of <100 mL and >450 mL.

Of the 90 patients included in the study nine could not void with the urodynamic catheter in situ, and the remaining 81 were divided into three groups according to the PVR, i.e., A (30 men, PVR < 100 mL, a control group having BOO with no chronic retention); B (30, PVR 100–450 mL, with BOO and chronic retention); and C (21, PVR > 450 mL, with BOO and chronic retention). We used a computer program to calculate the sample size that would give a power of 80% and a significance level of 5%, and this showed that including ⩾21 patients in each group and ⩾65 patients in the full study would achieve these power and significance levels.

Results

The mean (SD) age of the patients was 61.6 (11.9) years and the cause of infravesical obstruction was benign prostatic enlargement in 76 (prostate volume 55–90 mL) and bladder-neck obstruction in 14. Cystoscopy of these 14 patients showed a narrow and high bladder neck that was pliable, without contracture or fibrosis, suggesting a bladder neck dysfunction. Clinically, obstructive urinary symptoms were more common in groups A and B than C (mean IPSS 22, 28 and 13, respectively) with a statistically significant difference (P < 0.001). Overflow incontinence and nocturnal wetting were more apparent in group C than groups A and B (10/21, 0/30 and 2/30 patients, respectively, P < 0.001). Renal impairment and bilateral hydronephrosis (assessed by ultrasonography) were also more prevalent in group C than in groups A and B (mean serum creatinine levels of 2.3, 1 and 0.9 mg/dL, respectively; P < 0.001).

Analysis of the results of the filling phase of the urodynamic studies showed that the bladder capacity increased with the increase in the PVR among the three groups. Assessing the mean (SD) PVR in the three groups compared with the mean (SD) bladder capacity, the PVR was <20%, 20–70% and >70% of the bladder capacity in groups A, B and C, respectively.

The detrusor compliance was also low in all groups but with no statistically significant difference. Detrusor overactivity was significantly lower in group C than in groups A and B (P = 0.048; ).

Table 1 The results for the different urodynamic variables in the three study groups.

In the voiding phase, the voided volume and Qmax decreased significantly as the PVR increased (P < 0.001 and 0.015, respectively; ). The urethral resistance increased from group A to B to C, as shown by the significantly greater URF in group B than in group A (P = 0.005) and the further increase in group C above both groups A and B (P < 0.001 and 0.096, respectively; ).

The PdetQmax was significantly high in group B, followed by group A then group C (P = 0.028 and 0.018, respectively). The effect on the opening pressure was similar, being significantly higher in group B than group A and group C (P = 0.01 and 0.04, respectively; ). Group C had the lowest BCI, with a statistically significant difference from both groups A and B (P < 0.001). However, group B had a higher BCI than both groups A and C (P < 0.001). Also, group B had the longest duration of contraction, with statistically significant difference from group A (P < 0.02) but not from group C (P = 0.4; ).

Discussion

The precise definition of the detrusor compensatory response to BOO is still controversial [Citation11,Citation12]. To date there is no agreement among urologists about the exact time at which detrusor compensation reaches its maximum limit before the bladder starts to fail [Citation13,Citation14]. We attempted to find a urodynamic explanation for the natural progress of chronic retention in men.

In the present study men with BOO were divided into one of three groups, with group A having obstructive symptoms with an obstructed voiding pattern on PFS but with an insignificant PVR. Group B had a significant PVR and an obstructed PFS pattern but still had good contractility. In group C the contractility was weakened, resulting in a greater PVR with an obstructed PFS pattern.

We tried to determine the cause of the progressive accumulation of the PVR in these patients; is it an increased outlet resistance, or bladder failure, or both. In group B the bladder contractility was good and even higher than that in group A, and the only factor responsible for the PVR was the increased outlet resistance. However, group C had a continuous increase in the urethral resistance with a concomitant decrease in the contractility, implying that both factors contributed to a greater PVR.

Most of the urodynamic variables showed that group B had the best contractility amongst the three groups, as shown by the highest PdetQmax, the highest BCI and the longest duration of contraction. However, group C had the lowest contractility amongst the three groups, as shown by the lowest PdetQmax, lowest BCI and, interestingly, the lowest incidence of detrusor overactivity (which requires a working detrusor muscle).

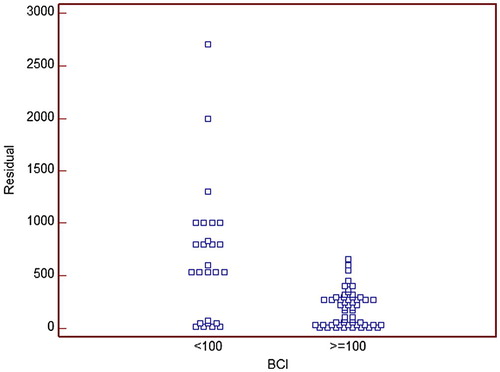

The ROC curve and scatter blots were very helpful for determining the point at which bladder compensation reaches its maximum limit before the bladder contractility changes from good to weak. The ROC curve showed that a PVR threshold of 450 mL had the best sensitivity and specificity to detect this change (). This was confirmed by scatter blots, where most of the data from patients with good contractility (BCI ⩾ 100) were in the area with a PVR of <450 mL ().

Figure 2 The scatter plots of BCI and PVR, showing that most of the patients with good contractility (BCI ⩾ 100) were in the area with a PVR of <450 mL.

There is still a debate about the use of the PVR as a predictor of acute urinary retention (AUR) in patients with BPH or after TURP. Some authors believe that the PVR is not a strong predictor of AUR [Citation15,Citation16], while others report that men were 3.6 times more likely to have a recurrence of AUR after TURP if they had a preoperative PVR of ⩾500 mL [Citation17]. The present study supports the second opinion, because in this group of patients the bladder contractility is very weak, raising the possibility of postoperative AUR.

In conclusion, in men with BOO, the PVR results from an increasing outlet resistance at the start and up to a PVR of 450 mL, where the bladder reaches its maximum compensation and power of contractility. With a PVR of >450 mL both the outlet resistance and bladder failure operate together, leading to detrusor decompensation.

Conflict of interest

None.

Source of funding

None.

Notes

Peer review under responsibility of Arab Association of Urology.

References

- M.SullivanS.YallaDetrusor contractility and compliance characteristics in adult male patients with obstructive and non-obstructive voiding dysfunctionJ Urol155199619952000

- J.SmithJ.PierceThe development of vesical trabeculationF.HinmanJ.BoyarskyBenign prostatic hypertrophy1983Springer-VerlagNew York682688

- M.SullivanC.DuBeauN.ResnickE.G.CravalhoS.V.YallaContinuous occlusion test to determine detrusor contractile performanceJ Urol154199518341837

- A.ElbadawiS.YallaN.ResnickStructural basis of geriatric voiding dysfunction. IV. Bladder outlet obstructionJ Urol150199316811684

- J.AbarbnelE.MarcusImpaired detrusor contractility in community-dwelling elderly presenting with lower urinary tract symptomsUrology692007436439

- P.GallienJ.ReymannG.AmarencoB.NicolasM.de SèzeE.BellissantPlacebo controlled randomized double blind study of the effects of botulinum A toxin in detrusor sphincter dyssynergia in multiple sclerosis patientsJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry76200516701673

- I.Botker-RasmussenB.BagiJ.B.JorgensonIs bladder outlet obstruction normal in elderly men without lower urinary tract symptoms?Neurourol Urodyn181999545548

- I.GhalayiniM.Al-GhazoR.PickardA prospective randomized trial comparing transurethral prostatic resection and clean intermittent self-catheterization in men with chronic urinary retentionBJU Int9620059397

- P.AbramsBladder outlet obstruction index, bladder contractility index and bladder voiding efficiency: three simple indices to define bladder voiding functionBJU Int8419991415

- M.D.EckhardtG.E.van VenrooijT.A.BoonUrethral resistance factor (URA) versus Schäfer’s obstruction grade and Abrams-Griffiths (AG) number in the diagnosis of obstructive benign prostatic hyperplasiaNeurourol Urodyn202001175185

- S.KaplanA.WeinD.StaskinC.G.RoehrbornW.D.SteersUrinary retention and post-void residual urine in men: Separating truth from traditionJ Urol18020084754

- P.RosierM.deWildtJ.de la RosetteF.M.DebruyneH.WijkstraAnalysis of maximum detrusor contraction power in relation to bladder emptying in patients with lower urinary tract symptoms and benign prostatic enlargementJ Urol145199621372142

- P.AbramsM.DunnN.GeorgeUrodynamic finding in chronic retention of urine and their relevance to results of surgeryBMJ162197812581260

- N.GeorgeP.O’ReillyR.BarnardN.J.BlacklockHigh pressure chronic retentionBMJ286198317801783

- C.RoehrbornS.KaplanM.Leeet alBaseline post void residual urine volume as a predictor of urinary outcomes in men with BPH in MTOPS studyJ Urol1732005443 [abstract 1638]

- E.CrawfordS.WilsonJ.McConnellK.M.SlawinM.C.LieberJ.A.Smithet alBaseline factors as predictors of clinical progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia in men treated with placeboJ Urol175200614221425

- P.KlarskovJ.AndersonC.AsmussenJ.BrenøeS.K.JensenI.L.Jensenet alSymptoms and signs predictive of the voiding pattern after acute urinary retention in menScand J Urol2119872326