Abstract

Objective:

To determine the efficacy and safety of the laparoscopic management of an impacted distal ureteric stone in a bilharzial ureter, as bilharzial ureters are complicated by distal stricture caused by the precipitation of bilharzial ova in the distal ureter. These cases are associated with poorly functioning and grossly hydronephrotic kidneys that hinder the endoscopic manipulation of the coexistent distal high burden of, and long-standing, impacted stones.

Patients and methods:

We used laparoscopic ureterolithotomy, with four trocars, to manage 51 bilharzial patients (33 men and 18 women; mean age 40.13 years) with distal ureteric stones. The ureter was opened directly over the stone and the stone was extracted. A JJ stent was inserted into the ureter, which was then closed with a 4–0 polyglactin running suture.

Results:

The mean stone size was 2.73 cm. Conversion to open surgery was required in only one patient. The mean operative duration was 92 min, the postoperative pain score was 20–60, the mean (range) number of analgesic requests after surgery was 1.72 (1–3), comprising once in 21 patients, twice in 23 and thrice in seven. The mean hospital stay was 2.74 days, and the total duration of follow-up was 7–12 months. The stone recurred in four patients and a ureteric stricture was reported in two. All patients were rendered stone-free.

Conclusion:

Laparoscopy is a safe and effective minimally invasive procedure for distal ureteric stones in a bilharzial ureter with hydronephrosis.

Abbreviation:

Introduction

Schistosomes (bilharzia) are parasites that have been documented to cause urinary disease in humans since ancient times, as recorded in Egyptian papyri, notably those of Eber and Edwin Smith [Citation1]. Schistosomiasis is the second most important parasitic infection after malaria and affects >200 million people in 74 countries [Citation2]. It is endemic, with high prevalence and morbidity rates, in many countries, especially those in Africa, such as Egypt and Kenya, and in South America, mainly Brazil, with a prevalence of 15–45% in Egypt and Brazil [Citation3–Citation5].

Commonly, ureteric lesions are limited to the lower half, at the level of the third lumbar vertebra, which is due to anastomotic channels between the inferior mesenteric and the peri-ureteric and peri-vesical veins. These communications are thought to be the main route through which Schistosoma haematobium worms migrate to the urinary system. The lower ureteric lesions in schistosomiasis include early tubercles and ulcers, and subsequently the sandy patches and cysts, known as ‘ureteritis cystica’. Fibrosis of the lower ureteric musculosa can lead to partial obstruction; the upper ureter compensates by dilatational hypertrophy that generates enough bolus pressure to overcome the distal obstruction, thereby protecting the kidneys from back pressure [Citation6].

Laparoscopic ureterolithotomy (LU) is a safe well-established treatment option for managing ureteric stones, replacing conventional surgery [Citation7,Citation8]. LU causes less pain, and has a minimal analgesic requirement, a short hospital stay, a shorter recovery phase and better cosmesis [Citation9,Citation10]. LU is done using one of two basic approaches, transperitoneal or retroperitoneal, and each has its advantages and disadvantages [Citation11–Citation13].

Bilharzial ureters are complicated mainly by the distal stricture caused by the precipitation of bilharzial ova at the vesico-ureteric junction and distal ureter. This is associated with poorly functioning and grossly hydronephrotic kidneys that hinder the endoscopic manipulation of the coexistent distal, high-burden, long-standing impacted stones making it technically unfeasible [Citation14].

In the present study we aimed to determine the efficacy and safety of the laparoscopic management of an impacted distal ureteric stone in bilharzial patients.

Patients and methods

This prospective study follows the tenets of the declaration of Helsinki. We used transperitoneal LU in 51 bilharzial patients (33 men and 18 women) who had large radio-opaque distal ureteric stones, during the period from June 2010 to June 2013. All patients were assessed by IVU and this showed gross hydronephrosis in 45 renal units. The inclusion criteria were: large lower ureteric stones (⩾1 cm) visible on a plain film and not amenable to ureteroscopic extraction, hydronephrosis associated with a history of antibilharzial treatment for confirmed bilharzial ova on urine analysis, a radiological appearance of the spindle-shaped lower ureteric stricture characteristic of bilharzial infection, or the presence of ureteritis cystica on ureteroscopy.

Surgical technique

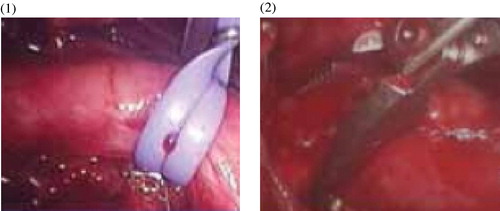

The procedure usually starts with cystoscopy and insertion of an open-tip 6 F ureteric catheter, and then the stone side is laterally tilted to 45°. The LU was performed through four ports, comprising two 10-mm and two 5-mm trocars. After reflecting the colon, the ureter was identified and the stone located and extracted through vertical ureterotomy. The stone was identified by an obvious bulge, or pinching by Maryland forceps. Upward migration of the stone was prevented by applying a laparoscopic Babcock forceps on the ureter above the stone bulge, which was replaced by a vessel tape in some cases, according to the surgeon’s preference. This was followed by ureterotomy and stone extraction (). A 6 F JJ stent was then inserted and the ureterotomy closed with 4/0 polyglactin sutures. Using a 5-mm endoscope, the stone was extracted in a sac through the 10-mm port and then a small drain was inserted via the other 5-mm port.

Figure 1 The important surgical steps in transperitoneal LU: (1) Proximal control of the ureter; (2) Ureteric pinching.

The data collected included patient age, sex, stone details (size, number and laterality) and any history of stone surgery or ESWL. Operative data included the type of anaesthesia applied, operative duration, mean intraoperative blood loss, and the frequency of conversion to open surgery. Postoperative data included pain severity, judged using 100-point visual analogue scale with 0 = no pain and 100 = the worst intolerable pain, the duration until the first request and the number of requests for analgesia, the time to resuming oral intake, time to first mobilisation, and the duration of hospital stay. The follow-up data included the duration of follow-up, any stone recurrence, ureteric stricture formation, and any other complications.

Results

The results are shown in ; conversion to open surgery was reported in only one patient. The stone recurred in four patients (8%) during the follow-up, and all were small and passed spontaneously with medical treatment. A ureteric stricture was reported in two patients (4%) and these were managed endoscopically. All patients were rendered stone-free rate.

Table 1 The pre- and postoperative characteristics of the 51 patients.

Discussion

LU or open ureterolithotomy can be used as the primary treatment of large, impacted ureteric stones of >1 cm, or as a salvage procedure if ESWL fails or after attempted ureteroscopy and percutaneous nephrolithotomy [Citation14–Citation16].

As LU can access all locations in the ureter, LU by the transperitoneal route is the preferred technique for ureteric stones [Citation17,Citation18]. The advantages of the transperitoneal route included a large peritoneal space for instrument handling and intracorporal suturing, making the procedure comparatively easy [Citation19]. In addition, the transperitoneal approach gives a better understanding of the anatomical landmarks, particularly for a lower ureteric stone [Citation11]. Thus we used this technique in the present study.

In the present study all patients were ultimately stone-free (complete clearance of the stones). These results are comparable to those of previous studies, where it was reported that a high success rate depends upon correct patient selection and the surgical experience of the laparoscopic technique. The success rates of transperitoneal LU are 86–100% [Citation17,Citation20–Citation22]. Further studies showed that with increase in experience, the overall success rate is >90% [Citation8,Citation23].

In the present study the mean (SD, range) operative duration was 92.1 (10.60, 75–120) min; El-Feel et al. [Citation24] reported a mean duration of 145 (55–180) min. The present operative duration seemed to be longer than in other previous reports, and this can be attributed to the fact that we operated only on lower ureteric stones, while previous reports included stones in all segments in the ureter. For lower ureteric stones the ureter was dissected with extra caution, where the space was less, and as the ureter was crossing the iliac vessels there were more chances of vascular injury. Compared to other locations the overall procedure time was more for stones which were in the lower ureter [Citation25]. Abolyosr et al. [Citation26] reported that upper and mid ureteric stones can be safely approached retroperitoneally, but for lower ureteric stones transperitoneal approach is a much better option, as it gives a better understanding of the anatomical landmarks, particularly in the lower part of the ureter.

The overall complication rate in the present study was 11.7% (conversion, re-stricture and stone recurrence). This is in line with previous reports, where the overall reported mean complication rate of laparoscopic transperitoneal urological surgery is 14.1–19% [Citation27,Citation28] and for transperitoneal ureterolithotomy, the rate was 4–18% in different series [Citation20,Citation24,Citation29]. Feyaerts et al. [Citation21] reported an overall 8.3% complication rate of transperitoneal LU, and El-Feel et al. [Citation24] reported 4% and Simforoosh et al. [Citation20] reported 12.2%, respectively. In an interesting study, Basiri et al. [Citation17] reported an 18% complication rate, in the form of leakage of urine for >3 days.

The present mean (SD, range) duration of hospital stay was 2.7 (0.91, 2–5) days. Feyaerts et al. [Citation21] reported a mean hospital stay of 3.8 days, El-Feel et al. [Citation24] of 4.1 days and Basiri et al. [Citation17] of 5.8 (2.3) days. Fang et al. [Citation30] reported LU to give a higher stone clearance rate and shorter operating time than ureteroscopic lithotripsy.

The present study had several limitations: it did not include patients with previous ureteric surgery or those with multiple stones. The patients were operated by several surgeons with different levels of experience.

In conclusion, we showed that LU is a safe and effective minimally invasive procedure for distal ureteric stones in the bilharzial ureter that were not otherwise amenable to endoscopic extraction.

Conflict of interest

None.

Source of funding

None.

Notes

Peer review under responsibility of Arab Association of Urology.

References

- J.B.RaddinMagic and medical science in ancient EgyptArch Intern Med111964925

- WHO Expert CommitteePrevention and control of schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasisWorld Health Organ Tech Rep Ser912i–vi2002157

- T.El-KhobyN.GalalA.FenwickR.BarakatA.El-HaweyZ.Noomanet alThe epidemiology of schistosomiasis in Egypt: summary findings in nine governoratesAm J Trop Med Hyg62Suppl. 220008899

- R.E.BlantonE.A.SalamH.C.KariukiP.MagakL.SilvaE.M.Michiriet alPopulation-based differences in Schistosomiasis mansoni and hepatitis C induced diseaseJ Infect Dis185911200216441649

- D.C.C.PalmeiraA.G.CarvalhoK.RodriguesJ.L.A.CoutoPrevalência da infecção pelo Schistosoma mansoni em dois municípios do Estado de AlagoasRev Soc Bras Med Trop432010313317 (English abstract)

- R.S.BarsoumUrinary schistosomiasisRev J Adv Res2013453459

- T.AnagnostouD.TolleyManagement of ureteric stonesEur Urol452004714721

- J.S.WolfJr.Treatment selection and outcomes: ureteral calculiUrol Clin North Am342007421430

- C.LeonardoG.SimoneP.RoccoS.GuaglianoneG.Di PierroM.Gallucciet alLaparoscopic ureterolithotomy: minimally invasive second line treatmentInt Urol Nephrol432011651654

- T.KnollP.AlkenM.S.MichelProgress in management of ureteric stonesEAU Update Ser320054450

- D.D.GaurS.TrivediM.R.PrabhudesaiH.R.MadhusudhanaM.Gopichandet alLaparoscopic ureterolithotomy: technical considerations and long-term follow-upBJU Int892002339343

- M.T.GettmanJ.W.SeguraManagement of ureteric stones: issues and controversiesBJU Int9520058593

- S.J.Farooq QadriN.KhanM.KhanRetroperitoneal laparoscopic ureterolithotomy – a single centre 10 year experienceInt J Surg92011160164

- E.RiadA.AzizM.RoshdyA.ElbazLaparoscopic management of distal ureteric stones in bilharzial ureterUrol74Suppl. 4A2009S154

- G.L.AlmeidaF.L.HeldweinT.M.GraziotinC.S.SchmittC.TelokenProspective trial comparing laparoscopy and open surgery for management of impacted ureteral stonesActas Urol Esp33200911081114

- V.SinghR.J.SinhaD.K.GuptaM.KumarA.AkhtarTransperitoneal versus retroperitoneal laparoscopic ureterolithotomy: a prospective randomized comparison studyJ Urol1892013940945

- A.BasiriN.SimforooshA.ZiaeeH.ShayaninasabS.M.MoghaddamS.ZareRetrograde, antegrade, and laparoscopic approaches for the management of large, proximal ureteral stones: a randomized clinical trialJ Endourol22200826772680

- A.MandhaniR.KapoorLaparoscopic ureterolithotomy for lower ureteric stones: steps to make it a simple procedureIndian J Urol252009140142

- T.O.HenkelJ.RassweilerP.AlkenUreteral laparoscopic surgeryAnn Urol (Paris)2919956172

- N.SimforooshA.BasiriA.K.DaneshS.A.ZiaeeF.SharifiaghdasA.Tabibiet alLaparoscopic management of ureteral calculi: a report of 123 casesUrol J42007138141

- A.FeyaertsJ.RietbergenS.NavarraG.VallancienB.GuillonneauLaparoscopic ureterolithotomy for ureteral calculiEur Urol402001609613

- I.TurkS.DegerJ.RoigasD.FahlenkampB.SchonbergerS.A.LoeningLaparoscopic ureterolithotomyTech Urol419982934

- M.G.El-MoulaA.AbdallahF.El-AnanyY.AbdelsalamA.AbolyosrD.Abdelhameedet alLaparoscopic ureterolithotomy: our experience with 74 casesInt J Urol152008593597

- A.El-FeelH.Abouel-FettouhA.M.Abdel-HakimLaparoscopic transperitoneal ureterolithotomyJ Endourol2120075054

- M.GargV.SinghR.J.SinhaS.N.SankhwarM.KumarA.Kumaret alProspective randomized comparison of open versus transperitoneal laparoscopic ureterolithotomy: experience of a single center from Northern IndiaCurr Urol720138389

- A.AbolyosrLaparoscopic transperitoneal ureterolithotomy for recurrent lower ureteral stones previously treated with open ureterolithotomy: initial experience in 11 casesJ Endourol212007525529

- Y.H.LinH.J.ChungA.T.LinY.H.ChangW.J.HuangY.S.Hsuet alComplications of pure transperitoneal laparoscopic surgery in urology: the Taipei Veterans General Hospital experienceJ Chin Med Assoc702007481485

- G.VallancienX.CathelineauH.BaumertJ.D.DoubletB.GuillonneauComplications of transperitoneal laparoscopic surgery in urology: review of 1,311 procedures at a single centerJ Urol16820022326

- G.M.PremingerH.G.TiseliusD.G.AssimosP.AlkenA.C.BuckM.Gallucciet al2007 guideline for the management of ureteral calculiEur Urol52200716101631

- Y.Q.FangJ.G.QiuD.J.WangH.L.ZhanJ.SituComparative study on ureteroscopic lithotripsy and laparoscopy ureterolithotomy for treatment of unilateral upper ureteral stonesActa Cir Bras272012266270