Abstract

Objective:

To determine the efficacy and safety of solifenacin for correcting the residual symptoms of an overactive bladder (OAB) in patients who were treated for a urinary tract infection (UTI).

Patients and methods:

Using random sampling, 524 patients aged >60 years were selected (347 women, 66.2%, and 177 men, 33.8%). They denied the presence of any symptoms of detrusor overactivity in their medical history, but had a diagnosis of a UTI. At least 1 month after the end of treatment and a laboratory confirmation of the absence of infection, each patient completed an OAB-Awareness Tool questionnaire (OAB signs, total score 8 points), and a noninvasive examination of urinary function (uroflowmetry).

Each day patients in group A took solifenacin 10 mg and those in group B took 5 mg, with patients in group C being given a placebo.

Results:

During the study 58.8% of patients had symptoms of an OAB at 1 month after the end of the treatment for a UTI, and normal laboratory markers. During treatment with the standard and higher dose of solifenacin, within 8 weeks most variables of the condition of the lower urinary tract reached a normal state or improved.

Conclusion:

Patients aged >60 years who had been treated for a UTI have a high risk of developing symptoms of an OAB. Solifenacin in standard doses is an efficient and safe means of managing overactive detrusor symptoms after a UTI.

Introduction

UTIs in elderly men and women are common and the prevalence depends on numerous factors. The frequency of UTI depends on the place of residence, climate, age, the presence of urodynamic disorders, compliance with treatments for overactive bladder (OAB) symptoms, the immunological status, and many other factors [Citation1–Citation3]. The absence of a common approach (‘gold standard’) to the diagnostics and treatment of UTI complicates the well-timed detection and appropriate therapy of this disease. As a rule, existing principles of UTI management duplicate the recommendations for treating younger groups and, according to several studies, allow an excessive use of antibiotics [Citation2–Citation4]. Nevertheless, most specialists consider the availability of laboratory findings such as pyuria and a positive urine culture (>105 colony-forming units/mL) with no more than two uropathogens, and such clinical symptoms as fever, acute dysuria, urgency, increase in urinary frequency, pain or hypersensitivity in the area of bladder [Citation4,Citation5], to be sufficient to establish a diagnosis of UTI. Some of these symptoms are also the signs of an OAB [Citation6,Citation7]. Many researchers assume that, at least in some cases, OAB and UTI are interdependent processes and UTIs can be one of the reasons for the development of an OAB. Rodrigues et al. [Citation8] reported involuntary detrusor contraction in 86.3% of patients with a UTI. Moore et al. [Citation9] noted that despite the presence of different views on the mechanisms of formation of an OAB in cases of UTI, many researchers do not deny the cause-and-effect relationship between these conditions. It is common knowledge that OAB symptoms, especially frequency and imperative desire to urinate, cause involuntary urination that compromises the quality of life of elderly people, both men and women [Citation10,Citation11].

Numerous studies have assessed solifenacin as a first-line drug for treating an OAB in elderly people [Citation12,Citation13]. Solifenacin is competitive inhibitor of M3 antimuscarinic receptors that comprise ⩾22% of all bladder cholinoreceptors, and play a key role in maintaining its normal physiological function [Citation14]. Solifenacin is 3.6 times as selective for bladder receptors than for those in salivary glands. The indisputable advantages of this drug include the absence of addiction and a lasting result during long periods of use [Citation15–Citation17].

All these properties give a high efficacy and tolerability of solifenacin in elderly men and women, while taking this drug in increased dosages generally does not increase the number of adverse effects [Citation18–Citation21].

Previously we reported success in controlling the symptoms of OAB using standard and increased dosages of solifenacin and trospium in elderly persons [Citation22–Citation24]. Given these conditions, in the present study we assessed the efficacy and safety of solifenacin for treating residual symptoms of OAB in patients who had been treated for a UTI.

Patients and methods

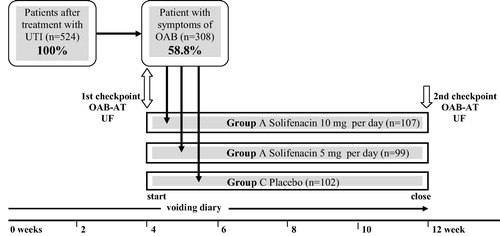

This was a placebo-controlled longitudinal study in patients aged >60 years who sought medical attention in the Urological Department of the 3rd Municipal Hospital (Vladivostok, Russian Federation) from 1 March to 31 December 2012. For this study, 524 patients (347 women, 66.2%, 177 men, 33.8%) who had been diagnosed with a UTI were selected using blinded random sampling. All of them denied the presence of signs of an OAB in their medical history. The study design is shown in . At least 1 month after the end of treatment, and laboratory confirmation of the absence of UTI (positive urine culture, ⩽105 colony-forming units/mL, a physiologically normal number of white and red blood cells in urine, and normal urine density) each patient completed the OAB-Awareness Tool (AT) questionnaire (OAB signs, total 8 points) [Citation25,Citation26], and had a noninvasive examination of urinary function (uroflowmetry) [Citation27–Citation29]. These results were taken as the baseline and determined the percentage of patients with signs of OAB, and the severity of symptoms. All patients with ОAB symptoms were randomly divided into three groups: A (107 patients, mean age 67.2 years), B (99, 65.9 years) and C (102, 65.1 years). Each day the patients in group A took solifenacin 10 mg, and those in group B 5 mg, with group C taking a placebo. The patients were assessed over 2 months, using urinary diaries, and a final assessment with the OAB-AT questionnaire and uroflowmetry. The efficacy of the treatment was assessed clinically by determining the number of urgency episodes (UE), incontinence episodes (IE), and episodes of daytime urination [Citation30–Citation32]. The second endpoint was a comparison of the conditions of the lower urinary tract (LUT) in the patients of each group after the treatment (see ).

The results were analysed statistically by comparing those before and after treatment using the Wilcoxon test, comparing the medians at the three sample times using the Kruskal–Wallis criterion, and analysing the sample contingency using the Spearman index. In all tests, P < 0.05 was considered to indicate significant differences.

Results

At 1 month after the end of treatment and the confirmed absence of laboratory signs of UTI, the results of the OAB-AT questionnaire, urinary diaries and uroflowmetry showed that ОAB symptoms were reported in 308 patients (192 women and 116 men, 58.8%). Most patients had symptoms of mild and medium severity (258, 83.8%). Patients complained mostly about an excessive frequency of urination throughout the day and night, and episodes of urgency.

Variables of the LUT before and after solifenacin treatment are shown in . In group A, all values after the treatment differed significantly from baseline (some at P < 0.01). In group B the variability against the background of treatment was not as obvious, but most variables were significantly different from baseline. The mean (SD) night-time frequency according to both the OAB-AT questionnaire, of 1.7 (1.0) decreasing to 0.5 (0.5) (P > 0.01) and urinary diaries, of 2.3 (1.1) decreasing to 0.9 (0.6) (P > 0.01), were an exception. The variability in the maximum urinary flow rate for this group also increased unreliably, in contrast to the mean flow rate. The results in group C were not significantly different from baseline for all variables.

Table 1 Change in OAB questionnaire scores, urinary diary variables and uroflowmetry symptoms before and after treatment (308 patients).

After the end of treatment, the results were similar and there were no statistically significant differences in all variables between groups A and B, but there was a considerable difference between groups A and B and group C. The significant differences between the mean results in A and B and the control group are shown in the last column of . According to the OAB-AT questionnaire, the differences between final values of UE and IE in groups A and C was significant (P < 0.01). The differences between the final values in patients taking different doses of solifenacin were insignificant (P < 0.05). The differences between these groups and the control group were statistically significant (P < 0.05). For example, according to OAB-AT questionnaire, the daytime frequencies in those taking solifenacin were substantially lower than in group C, at 1.4 (0.8) and 1.4 (0.8) points, vs. 3.7 (1.2) (P < 0.05 in both cases). From the urinary diaries, the mean (SD) number of IE in groups A and B was lower than that in group C, at 0.1 (0.1) and 0.1 (0.1) vs. 0.5 (0.2) (P < 0.05 in both cases). Differences between the mean values of UE in group C and in groups A and B were marginal and statistically insignificant.

The uroflowmetry results showed a similar change in values. There were no differences between groups A and B, but significant differences in both the average and maximum flow rate between these groups and group C. The most significant (P < 0.01) was for the average flow rate in men (). The exception was for maximum flow rate in women between groups B and C (P > 0.05).

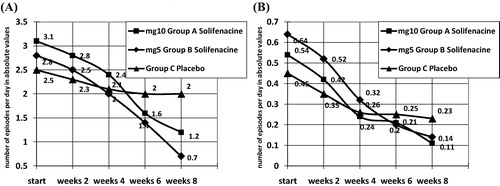

A plot of the variability of number of UE and IE is shown in . The trend of change in groups A and B shows a synchronous frequency reduction by 3–5 times from the initial values. Changes in the group C over the whole period of monitoring fall within the limits of statistical accuracy.

The correlation of variability of day-time and nocturnal urinary frequency, urgency and incontinence associated with treatment showed that in groups A and B the correlation of the variability of day-time urinary frequency gave r = 0.83 (P < 0.01). The correlation coefficient between groups A and C, and B and C, was r = 0.43 (P < 0.05) and r = 0.36 (P < 0.05), respectively. The Spearman coefficient for curves of the variability of mean nocturnal urinary frequency between groups A and B was 0.79 (P < 0.05), between groups A and C was 0.45 (P < 0.05), and between groups B and C was 0.39 (P < 0.05). The correlation of urgency frequency was 0.74 (P < 0.05) between groups A and B, 0.56 (P < 0.05) between groups A and C, and 0.51 (P < 0.05) between groups B and C. Finally, the Spearman coefficient between the variability of incontinence in groups A and B was 0.81 (P < 0.01), between groups A and C was 0.61 (P < 0.05), and between groups B and C was 0.52 (P < 0.05). Thus there was a strong direct dependence between changes in the values in groups taking different doses of solifenacin, and the medium and mild severity between these groups and group C.

In all, 13 patients (4.2%) refused treatment during the study, of whom three refused for reasons unrelated to the study (one in each group), three due to acute exacerbation of chronic diseases of visceral organs (one in group B, two in group C), five because of intolerable side-effects (four in group A, one in group C), and two due to lack of a treatment response (both in group C).

Side-effects were reported by 27 patients during the study, with complaints of dryness of the mouth (21 reported it, 12 in group A, eight in group B, one in group C) being the most numerous. Patients also noted episodes of faintness (two in group A), rash (one each in groups A and C), and diarrhoea (one each in groups B and C). There were no reported episodes of the acute urinary retention during the study.

Thus, only five (1.6%) patients refused to participate due to intolerable side-effects. Such effects of various degrees affected 27 others, but these patients found the intensity to be insufficient to justify stopping the treatment. The frequency and intensity of emergent adverse effects thus correlated with data of others who assessed the safety of solifenacin in elderly people.

Discussion

During the present study, 58.8% of patients aged >60 years had symptoms of an OAB at 1 month after the end of treatment for a UTI and the normalisation of laboratory markers. During the treatment of OAB symptoms with standard and high doses of solifenacin over 8 weeks, most of the variables of the LUT reached normal values or improved. There were significant changes in urodynamic variables in both groups treated with solifenacin. From this we assume that standard dose of solifenacin is sufficient in most cases to manage OAB symptoms typical of elderly patients after a UTI.

As noted, the pathogenesis of OAB is not sufficiently clear, despite numerous investigations [Citation33,Citation34]. Most potential mechanisms for causing OAB include a decrease in the number of efficient muscarinic receptors in the detrusor, episodic noise or a decrease of coordination of the afferent impulses, detrusor hypoxia, pelvic floor prolapse and others [Citation18,Citation34–Citation36]. We found that more than half of elderly patients have symptoms of an OAB in the month after a UTI (in most cases mild), which are corrected by standard doses of solifenacin. This correlates well with results from others and suggests that the bladder receptors are affected by toxins from pathogenic microorganisms during the inflammatory process [Citation9,Citation37–Citation39]. Muscarinic receptor function might also be influenced by the decreased oxygenation typical of any inflammation. However, in this case the decrease in the activity of receptors is inverse, transient and can be relatively easily treated with antimuscarinic agents, which as a rule stimulate M3 receptors that are not damaged in the ageing bladder.

The efficacy and safety of solifenacin for treating OAB symptoms in elderly men and women have been confirmed previously [Citation17], but with no correlation to the previous treatment of a UTI as a possible cause of the disease.

These assumptions undoubtedly need further study and clarification. Another field of study could be analysing the possibilities of decreasing the antimuscarinic drug dose.

In conclusion, patients aged >60 years who have had a UTI have a high risk of developing symptoms of an OAB. Solifenacin in standard doses is an efficient and safe means of managing OAB symptoms after a UTI. The use of high doses of solifenacin to correct residual OAB symptoms after a UTI is unreasonable.

Conflict of interest

None.

Source of funding

None.

Notes

Peer review under responsibility of Arab Association of Urology.

References

- T.A.RoweM.Juthani-MehtaUrinary tract infection in older adultsAging Health952013 10.2217/ahe.13.38

- I.ErikssonY.GustafsonL.FagerströmB.OlofssonDo urinary tract infections affect morale among very old women?Health Qual Life Outcomes8201073

- S.J.MatthewsJ.W.LancasterUrinary tract infections in the elderly populationAm J Geriatr Pharmacother92011286309

- T.A.RoweM.Juthani-MehtaDiagnosis and management of urinary tract infection in older adultsInfect Dis Clin North Am2820147589

- L.ModyM.Juthani-MehtaUrinary tract infections in older women: a clinical reviewJAMA3112014844854

- D.de RidderT.RoumeguèreL.KaufmanOveractive bladder symptoms, stress urinary incontinence and associated bother in women aged 40 and above; a Belgian epidemiological surveyInt J Clin Pract672013198204

- N.KuritaS.YamazakiN.Fukumoriet alOveractive bladder symptom severity is associated with falls in community-dwelling adults. The LOHAS StudyBMJ Open32013e002413

- P.RodriguesF.HeringJ.C.CampagnariInvoluntary detrusor contraction is a frequent finding in patients with recurrent urinary tract infectionsUrol Int9320146773

- K.H.MooreA.P.MalykhinaWhat is the role of covert infection in detrusor overactivity, and other LUTD?Neurourol Urodyn332014606610

- M.Espuña-PonsD.Castro-DíazH.Díaz-CuervoM.Pérezet alImpact of overactive bladder treatment on the quality of life of patients over 60 with associated pathologiesArch Esp Urol662013287294

- D.L.PatrickK.M.KhalafR.DmochowskiJ.W.KowalskiD.R.Globeet alPsychometric performance of the incontinence quality-of-life questionnaire among patients with overactive bladder and urinary incontinenceClin Ther352013836845

- J.P.Capo′V.LucenteS.Forero-SchwanhaeuserW.HeEfficacy and tolerability of solifenacin in patients aged >65 years with overactive bladder: post-hoc analysis of 2 open-label studiesPostgrad Med123201194104

- A.WaggG.CompionA.FaheyE.SiddiquiPersistence with prescribed antimuscarinic therapy for overactive bladder: a UK experienceBJU Int110201217671774

- K.J.MansfieldL.LiuF.J.MitchelsonK.H.MooreR.J.MillardE.BurcherMuscarinic receptor subtypes in human bladder detrusor and mucosa, studied by radioligand binding and quantitative competitive RT-PCR. changes in ageingBr J Pharmacol144200510891099

- K.IkedaS.KobayashiM.SuzukiK.MiyataM.TakeuchiT.Yamadaet alM(3) receptor antagonism by the novel antimuscarinic agent solifenacin in the urinary bladder and salivary glandNaunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol366200297103

- A.OhtakeM.UkaiT.HatanakaS.KobayashiK.IkedaS.Satoet alIn vitro and in vivo tissue selectivity profile of solifenacin succinate (YM905) for urinary bladder over salivary gland in ratsEur J Pharmacol4922004243250

- A.WaggJ.J.WyndaeleP.SieberEfficacy and tolerability of solifenacin in elderly subjects with overactive bladder syndrome: a pooled analysisAm J Geriatr Pharmacother420061424

- M.YoshidaK.MiyamaeH.IwashitaM.OtaniA.InadomeManagement detrusor dysfunction in the elderly: changes in acetylcholine and adenosine triphosphate release during agingUrology63Suppl. 120041723

- J.Y.ChunM.SongJ.Y.HanS.NaB.HongM.S.ChooClinical factors associated with dose escalation of solifenacin for the treatment of overactive bladder in real life practiceInt Neurourol J1820142330

- R.NatalinF.LorenzettiM.DambrosManagement of OAB in those over age 65Curr Urol Report142013379385

- B.AmendJ.HennenlotterT.SchäferM.HorstmannA.StenzlK.-D.SievertEffective treatment of neurogenic detrusor dysfunction by combined high-dosed antimuscarinics without increased side-effectsEur Urol53200810211028

- K.S.KosilovS.LoparevM.IvanovskayaL.KosilovaManagement of overactive bladder (OAB) in elderly men and women with combined, high-dose antimuscarinics without increased side effectsUrotoday Int J62013 Art 47

- K.KosilovS.LoparevM.IvanovskayaL.KosilovaMaintenance of the therapeutic effect of two high-dosage antimuscarinics in the management of overactive bladder in elderly womenInt Neurourol J172013191196

- K.S.KosilovS.LoparevM.IvanovskayaL.KosilovaEffectiveness of combined high-dosed trospium and solifenacin depending on severity of OAB symptoms in elderly men and women under cyclic therapyCent Eur J Urol6720144348

- K.S.CoyneT.ZyczynskiM.K.MargolisV.ElinoffR.G.Robertset alValidation of an overactive bladder awareness tool for use in primary care settingsAdv Ther222005381394

- K.S.CoyneM.K.MargolisT.BavendamR.RobertsV.Elinoffet alValidation of a 3-item OAB awareness toolInt J Clin Pract652011219224

- G.SinghM.LucasL.DolanS.KnightC.RamageP.Toozs HobsonMinimum standards for urodynamic practice in the UKNeurol Urodyn29201013651372

- W.SchaferP.AbramsL.LiaoA.MattiassonF.PesceA.Spangberget alInternational Continence Society. Good urodynamic practices: uroflowmetry, filling cystometry, and pressure-flow studiesNeurol Urodyn212002261274

- C.M.GomesS.ArapF.E.Trigo-RochaVoiding dysfunction and urodynamic abnormalities in elderly patientsRev Hosp Clín Fac Med S Paulo592004206215

- M.ParsonsC.L.AmundsenL.CardozoM.VellaG.D.WebsterA.C.CoatsBladder diary patterns in detrusor overactivity and urodynamic stress incontinenceNeurourol Urodyn262007800806

- C.L.AmundsenM.ParsonsL.CardozoM.VellaG.D.WebsterA.C.CoatsBladder diary volume per void measurements in detrusor overactivityJ Urol176200625302534

- K.OkamuraY.NojiriM.YamamotoM.KobayashiY.OkamotoT.YasuiQuestionnaire survey on lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) for patients attending general practice clinicsNihon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi432006498504

- J.P.HeesakkersF.CruzY.IgawaE.KocjancicOveractive bladder: pathophysiology, diagnostics, and therapiesAdv Urol2011863504

- T.L.GrieblingOveractive bladder in elderly men: epidemiology, evaluation, clinical effects, and managementCurr Urol Report142013418425

- K.E.AnderssonAntimuscarinics for treatment of overactive bladderLancet Neurol20044653

- K.GiannitsasA.AthanasopoulosMale overactive bladder: pharmacotherapy for the maleCurr Opin Urol232013515519

- E.HessdoerferK.JundtU.PeschersIs a dipstick test sufficient to exclude urinary tract infection in women with overactive bladder?Int Urogynecol J222011229232

- S.MouttalibS.KhanE.Castel-LacanalJ.GuillotreauX.De BoissezonB.Malavaudet alRisk of urinary tract infection after detrusor botulinum toxin A injections for refractory neurogenic detrusor overactivity in patients with no antibiotic treatmentBJU Int106201016771680

- T.Antunes-LopesC.D.CruzF.CruzK.D.SievertBiomarkers in lower urinary tract symptoms/overactive bladder: a critical overviewCurr Opin Urol242014352357