Abstract

Introduction

Coffin-Siris Syndrome (CSS) is a rare congenital malformation syndrome characterized with mild to severe developmental and cognitive delay, coarse facial features, fifth digit aplasia or hypoplasia associated with ectodermal, constitutional and organ-related (cardiac/neurological/gastrointestinal/genitourinary…) anomalies. Here, we have reported a successful anesthetic and airway management in a case of 5-year old boy with CSS who underwent congenital heart surgery.

Case report

A 5-year old male child weighing 14 kg, who was diagnosed as CSS underwent operation for the repair of partial atrioventricular septal defect and secundum atrial septal defect. This case report pertains to the successful anesthetic and airway management in the background of difficult airway and presence of various cardiac abnormalities.

Although patient was anticipated to be difficult for intubation due to laryngomalacia, micrognathia, macroglossia, tracheal intubation was performed without any difficulty using fiber-optic laryngoscopy.

At the end of the operation, the patient was transferred to the cardiovascular intensive care unit and was extubated when his spontaneous breathing was satisfactory 4 h later after the operation without any complication.

Results and discussion

CSS often requires surgery and anesthetic intervention. The abnormal facial and airway as well as mental related features may lead intubation difficult, potentially due to short neck, large tongue and lips, poor dentition and poor communication.

Thinking that the practicing anesthetist needs to have appropriate knowledge for this entity and the equipment for managing difficult airway should readily be available. One of these patients which successfully managed without any complication was described in this brief report.

1 Introduction

Coffin-Siris Syndrome (CSS), known as “fifth digit syndrome” is a rare congenital anomaly characterized by many variable signs and symptoms, varying degree of intellectual and motor developmental problems, “coarse” facial features, abnormalities of the fifth fingers; cardiac/neurological/gastrointestinal/genitourinary anomalies. Respiratory infections and difficult feeding are common during infancy [Citation1–Citation3].

Congenital heart abnormalities are also heterogeneous, observed more than 30% of cases [Citation4].

Airway management can be difficult because micrognathia, macroglossia, hypotonia, and lax joint can also be the problem as well as mental status due to poor communication [Citation2].

This report presents a successful anesthetic and airway management in a 5-year old boy with CSS who underwent congenital heart surgery.

2 Case report

A five-years-old boy with mental retardation, a height of 109 cm and weighs 14 kg having CSS was admitted to our hospital for the operation of congenital heart disease. At birth he had hypothyroidism, nephrocalcinosis, respiratory problems including snoring, noisy breathing, change of voice, recurrent croup, sleep apnea, partial atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD) with secundum atrial septal defect (ASD). Recurrent respiratory infections due to aspiration persisted throughout early childhood and feeding difficulties were present. Mental development was also significantly retarded.

Physical examination revealed three major must-have features of CSS, namely retarded mental and cognitive growth; coarse facies reflected by flat nasal bridge, abnormal ears, wide mouth, microglossia, full lips and micrognathia; hypoplastic fifth finger terminal phalanx and the three minor findings of the syndrome (hypotonia, pectus carinatus and laryngomalacia). Muscles were hypotonic and pectus carinatus was prominent (). The patient was scheduled for cardiac surgery for his cardiac abnormalities, partial AVSD and secundum ASD.

After premedication with midazolam (0.05 mg/kg IV) the patient was admitted to operating room. Continuous monitoring was performed by evaluation of noninvasive blood pressure, pulse-oximetry and electrocardiography. His initial vital signs showed blood pressure (BP) of 91/57 mmHg, pulse rate of 113 beats/min, respiratory rate of 31/min and oxygen saturation rate of 99%, and skin temperature was 36 °C.

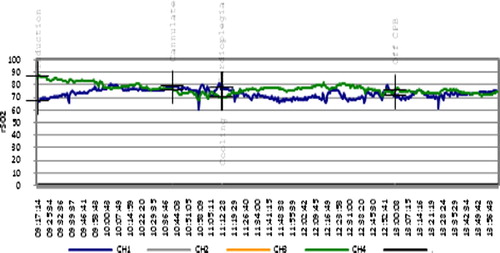

General anesthesia was initiated with 2 mcg/kg/min remifentanil infusion. Five minutes later, after establishing successful bag mask ventilation fiber-optic bronchoscopy (FOB) was carried out. Cuffed endotracheal tube number 5.5 mm internal diameter was safely placed into the trachea without trouble. Endotracheal cuff pressure was maintained among 10–15 cm H2O which was continuously monitored till extubation (). After confirming effective endotracheal intubation, sodium thiopental 4 mg/kg and rocuronium 0.6 mg/kg were given. Anesthesia was maintained with isoflurane 50% oxygen/air and continuous infusion of remifentanil (0.01–1 mcg/kg/min) until the end of surgical procedures with the aim of keeping index of consciousness (IOC) values within 40–60, heart rate and blood pressure within the 30% range.

Depth of anesthesia was monitored with index of consciousness (IOC, Morpheus Medical, Spain) [K]. Cerebral (rSO-C) and somatic (rSOS) tissue oxygen saturation were monitored, were stable, and did not change compared to the initial values during operation (). Data were continuously updated at two readings per second and average recordings saved at 1 min intervals (Pediatric SomaSensor, Model SPFB, for children 4–40 kg by Somanetics Corporation, Troy, Michigan for the INVOS 5100 Cerebral oximeter). Operation and anesthesia were uneventful. Remifentanil was preferred for slow induction of anesthesia being advantageous for hemodynamic stability in this case.

After operation, he was transferred to cardiovascular intensive care unit (CICU) where remifentanil infusion and IOC monitoring were continued. Sedation level was assessed by Ramsay Sedation Score (RSS), and pain level was evaluated by Children‘s Hospital Eastern Ontario Pain Scale (CHEOPS). In CICU, the patient was connected to Servo 300 ventilator (Siemens-Elema, Solna, Sweden). He received time-cycled SIMV volume control mode. When he remained stable clinically, ventilator support was changed first to SIMV rate of 8–10, PEEP 5 cm H2O and PS 6–8 cm H2O, then to CPAP of 5 cm H2O and PS 6–8 cm H2O. Then the patient was extubated four hours after operation without any problem. He woke up and started breathing spontaneously with a normal respiratory rate, tidal volume greater or equal to half the normal tidal volume for his age. He was discharged from CICU within 24 h and from hospital within 6 days without any complication.

3 Discussion

Congenital cardiac and vascular anomalies are not unique for, but frequently associated with CSS and significantly associated with congenital and acquired airway anomalies. In these patients, airway management can be difficult usually due to micrognathia and macroglossia [Citation4]. Laryngomalacia is the most common congenital laryngeal anomaly and most frequent cause of inspiratory stridor and airway obstruction [Citation5–Citation7].

Providing general anesthesia to patients with tracheolaryngomalacia can be an important challenge to the anesthesiologist in terms of type of anesthetic agent used, airway and ventilator management. Easy collapsibility of trachea during coughing and recovery from anesthesia may make intubation extremely difficult, leading to prolonged intubation and ventilation in these patients [Citation8,Citation9].

The most common cause of mortality and serious morbidity due to anesthesia is from airway problems. The Flexible fiberoptic endoscope is the most valuable single tool available for anesthesiologist to manage difficult airway [Citation10].

Fiber-optic intubation in awake state is recommended in cases with difficult airway. It could have been attempted at the onset with deeper sedation if spontaneous respirations could be maintained [Citation10,Citation11]. Alternatively, general anesthesia could have been induced and intubation performed with fiberoptic technique. In our case owing to the risks of detrimental effects of stress response on cardiac tissue in an awake state, we decided to proceed with intubation after establishing adequate depth of anesthesia.

After operation patient was transferred to CICU. We planned to apply fast track extubation that is why we used ultra-short acting opioid, remifentanil, during surgery and CICU [Citation12,Citation13].

Endotracheal cuff (ETTc) pressure monitored till extubation between the ranges of 10–15 cmH2O. Tracheal tube cuff should ideally seal the airway without compromising mucosal perfusion, and cuff pressure should be maintained around 10–15 cmH2O [Citation14,Citation15].

Achieving adequate depth of anesthesia during surgical procedures is desirable. We used IOC monitoring to determine the depth of anesthesia and to maintain optimal conditions for extubation [Citation16,Citation17].

With using transtracheal block and ultra-short opioid infusion, in order to provide smooth and uneventful perioperative course, successful fiberoptic intubation has been done in a patient with Coffin-Siris syndrome who has difficult airway and laryngomalacia. Moreover, by using ultra-short opioid infusion early extubation could be done.

We can conclude that for successful airway and anesthetic management in a case of CSS, one should have thorough and deep knowledge about the various anatomic abnormalities and pathophysiologic considerations so as to prevent any clinical disaster in the operation, especially for an elective surgery.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

Notes

Peer review under responsibility of Egyptian Society of Anesthesiologists.

References

- D.DimaculanganB.LokhandwalaD.R.WoodyR.GrossDifficult airway in a patient with Coffin-Siris syndromeAnesth Analg9222001554555

- Samir S.KhariwalaWalter T.LeePeter J.KoltaiLaryngotracheal consequences of pediatric cardiac surgeryArch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg1314200533633910.1001/archotol.131.4.336

- B.J.FleckA.PandyaL.VannerK.KerkeringJ.BodurthaCoffin-Siris syndrome: review and presentation of new cases from a questionnaire studyAm J Med Genet991200117

- L.NemaniR.BarikA.N.PatnaikR.C.MishraA.M.RaoP.KapurCoffinSiris syndrome with the rarest constellation of congenital cardiac defects: a case report with review of literatureAnn Pediatr Cardiol73201422122610.4103/0974-2069.140859

- T.KoshoN.MiyakeJ.C.CareyCoffin-Siris syndrome and related disorders involving components of the BAF (SWI/SNF) complex: historical review and recent advances using next generation sequencingAm J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet166C32014241251

- K.S.ChengJ.M.NgH.Y.LiP.M.HartiganVallecular cyst and laryngomalacia in infants: report of six cases and airway managementAnesth Analg955200212481250 [table of contents]

- F.MidullaR.GuidiG.TancrediS.QuattrucciF.RatjenS.BotteroMicroaspiration in infants with laryngomalaciaLaryngoscope114200415921596

- J.AustinT.AliTracheomalacia and bronchomalacia in children: pathophysiology, assessment, treatment and anaesthesia managementPaediatr Anaesth132003311

- Y.SutoY.TanabeEvaluation of tracheal collapsibility in patients with tracheomalacia using dynamic MR imaging during coughingAJR: Am J Roentgenol17121998393394

- R.A.StackhouseFiberoptic airway managementAnesthesiol Clin North Am202002930951

- Ascedio JoseRodriguesPaulo RogérioScordamaglioAddy MejiaPalominoEduardo QuintinoDe OliveiraMarciaJacomelliViviane RossiFigueiredoDifficult airway intubation with flexible bronchoscopeRev Bras Anestesiol6342013358361

- L.A.VricellaJ.A.DearaniS.R.GundryA.J.RazzoukS.D.BrauerL.L.BaileyUltra fast track in elective congenital cardiac surgeryAnn Thorac Surg6932000865871

- J.L.SchullerJ.G.BovillA.NijveldM.R.PatrickC.MarcellettiEarly extubation of the trachea after open heart surgery for congenital heart disease: a review of 3 years’ experienceBr J Anaesth56198411011108

- D.C.GuytonM.R.BarlowT.R.BesselievreInfluence of airway pressure on minimum occlusive endotracheal tube cuff pressureCrit Care Med2519979194

- L.S.EfferenA.ElsakrPost-extubation stridor: risk factors and outcomeJ Assoc Acad Minor Phys9419986568

- Y.PunjasawadwongA.PhongchiewboonN.BunchungmongkolBispectral index for improving anaesthetic delivery and postoperative recoveryCochrane Database Syst Rev62014CD00384310.1002/14651858

- T.Nguyen-KyP.P.WenY.LiR.GrayMeasuring andreflecting depth of anesthesia using wavelet and power spectral densityIEEE Trans Inf Technol Biomed1542011630639